Labia

The labia are part of the female genitalia; they are the major externally visible portions of the vulva. In humans, there are two pairs of labia: the labia majora (or the outer labia) are larger and thicker, while the labia minora are folds of skin between the outer labia. The labia surround and protect the clitoris and the openings of the vagina and the urethra.

Etymology

Labium (plural labia) is a Latin-derived term meaning "lip". Labium and its derivatives (including labial, labrum) are used to describe any lip-like structure, but in the English language, labium often specifically refers to parts of the vulva.

Anatomy

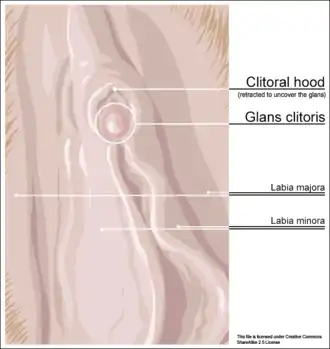

Right: Spreading the labia apart exposes inner areas of the vulva.

A) Anterior commissure of labia majora

B) Clitoral hood

C) Labia minora

D) Labia majora

E) Posterior commissure of labia majora

F) Clitoral glans

G) Inner surface of labia majora

H) Vulvar vestibule

I) Urethra

J) Vaginal orifice

K) Fourchette

The labia majora, also commonly called outer labia or outer lips, are lip-like structures consisting mostly of skin and adipose (fatty) tissue, which extend on either side of the vulva to form the pudendal cleft through the middle. The labia majora often have a plump appearance, and are thicker towards the anterior.[1] The anterior junction of the labia majora is called the anterior commissure, which is below the mons pubis and above the clitoris. To the posterior, the labia majora join at the posterior commissure, which is above the perineum and below the frenulum of the labia minora. The grooves between the labia majora and labia minora are known as the interlabial sulci or interlabial folds.

The labia minora (obsolete: nymphae), also called inner labia or inner lips, are two soft folds of fat-free, hairless skin between the labia majora. They enclose and protect the vulvar vestibule, urethra and vagina. The upper portion of each labium minora splits to join with both the clitoral glans, and the clitoral hood. The labia minora meet posterially at the frenulum of the labia minora (also known as the fourchette), which is a fold of skin below the vaginal orifice. The fourchette is more prominent in younger women, and often recedes after sexual activity[2] and childbirth.[1] When standing or with the legs together, the labia majora usually entirely or partially cover the moist, sensitive inner surfaces of the vulva, which indirectly protects the vagina and urethra,[1] much like the lips protect the mouth. The outer surface of the labia majora is pigmented skin, and develops pubic hair during puberty. The inner surface of the labia majora is smooth, hairless skin, which resembles a mucous membrane, and is only visible when the labia majora and labia minora are drawn apart.

Both the inner and outer surfaces of the labia majora contain sebaceous glands (oil glands), apocrine sweat glands, and eccrine sweat glands. The labia majora have fewer superficial nerve endings than the rest of the vulva, but the skin is highly vascularized.[2] The internal surface of the labia minora is a thin moist skin, with the appearance of a mucous membrane. They contain many sebaceous glands, and occasionally have eccrine sweat glands. The labia minora have many sensory nerve endings, and have a core of erectile tissue.[1]

Diversity

The color, size, length and shape of the inner labia can vary extensively from woman to woman.[3] In some women the labia minora are almost non-existent, and in others they can be fleshy and protuberant. They can range in color from a light pink to brownish black,[4] and texturally can vary between smooth and very rugose.[5]

Embryonic development and homology

The biological sex of an individual is determined at conception, which is the moment a sperm fertilizes an ovum,[3] creating a zygote.[6] The chromosome type contained in the sperm determines the sex of the zygote. A Y chromosome results in a male, and an X chromosome results in a female. A male zygote will later grow into an embryo and form testes, which produce androgens (primarily male hormones), usually causing male genitals to be formed. Female genitals will usually be formed in the absence of significant androgen exposure.

The genitals begin to develop after approximately 4 to 6 weeks of gestation.[6] Initially, the external genitals develop the same way regardless of the sex of the embryo, and this period of development is called the sexually indifferent stage.[4] The embryo develops three distinct external genital structures: a genital tubercle; two urogenital folds, one on either side of the tubercle; and two labioscrotal swellings, each bounding one of the urogenital folds.[2]

Sexual differentiation starts on the internal sex organs at about 5 weeks of gestation, resulting in the formation of either testes in males, or ovaries in females. If testes are formed, they begin to secrete androgens that affect the external genital development at about week 8 or 9 of gestation.[6] The urogenital folds form the labia minora in females, or penile shaft in males. The labioscrotal swellings become the labia majora in females, or they fuse to become the scrotum in males. Because the male and female parts develop from the same tissues, this makes them homologous (different versions of the same structure). Sexual differentiation is complete at around 12 weeks of gestation.[3][6]

Changes over time

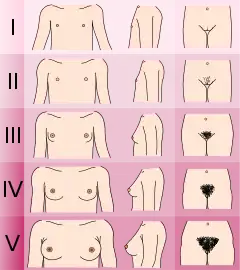

The genital tissues are greatly influenced by natural fluctuations in hormone levels, which lead to changes in labia size, appearance, and elasticity at various life stages. At birth, the labia minora are well-developed, and the labia majora appear plump due to being exposed to maternal hormones in the womb. The labia majora have the same color as the surrounding skin. Labial adhesions can occur between the ages of 3 months and 2 years, and may make the vulva look flat. These adhesions are not usually a cause for concern, and usually disappear without treatment. Treatment options may include estrogen cream, manual separation with local anesthesia, or surgical separation under sedation.[2]

During early childhood, the labia majora look flat and smooth because of decreasing levels of body fat, and the diminished effects of maternal hormones. The labia minora become less prominent.

During puberty, increased hormone levels often significantly change the appearance of the labia. The labia minora become more elastic, prominent, and wrinkled. The labia majora regain fat, and begin growing pubic hair close to the pudendal cleft. Hair is initially sparse and straight, but gradually becomes darker, denser, and curlier as growth spreads outward and upward toward the thighs and mons pubis. At the end of puberty, pubic hair will be coarse, curly, and fairly thick. The patch of pubic hair covering the genitals will eventually often form a triangle shape.[4]

By adulthood, the outer surface of the labia majora may be darker than the surrounding skin, and may have wrinkles similar to those on a male's scrotum. During the reproductive years, if a woman delivers a child, the fourchette will flatten. Pregnancy may cause the labia minora to darken in color.[3]

Later in life, the labia majora once again gradually lose fat, becoming flatter and more wrinkled, and pubic hair turns grey. Following menopause, falling hormone levels cause further changes to the labia. The labia minora atrophy, making them become less elastic, and pubic hair on the labia majora becomes more sparse.[2]

Sexual arousal and response

Right: The woman is sexually aroused, causing the inner and outer labia to swell, the labia majora to recede slightly, and the vulva to become lubricated.

The labia are one of a woman's erogenous zones. The labia minora are sexually responsive,[7] and sensitivity varies greatly between women. In some women, they are so sensitive that anything other than light touch may be uncomfortable, whereas stimulation may elicit no sexual response in others. The labia may be sexually stimulated as part of masturbation or with a sex partner, such as by fingering or oral sex. Moving the labia minora can also stimulate the extremely sensitive clitoris.

During sexual arousal, the labia majora swell due to increased blood flow to the region,[6] and draw back,[3] opening the vulva slightly. The labia minora become engorged with blood, causing them to expand in diameter by two to three times, and darken or redden in color.[6] Because pregnancy and childbirth increase genital vascularity, the inner and outer labia will engorge faster in women who have had children.[6]

After a period of sexual stimulation, the labia minora will become further engorged with blood approximately 30 seconds to 3 minutes before orgasm,[6] causing them to redden further.[6][8] In women who have had children, the labia majora may also swell significantly during this period, becoming dark red. Continued stimulation can result in an orgasm, and the orgasmic contractions help remove blood trapped in the inner and outer labia, as well as the clitoris and other parts of the vulva, which causes pleasurable orgasmic sensations.

Following orgasm or when a woman is no longer sexually aroused, the labia gradually return to their unaroused state.[6] The labia minora return to their original color within 2 minutes, and engorgement dissipates in about 5 to 10 minutes.[4] The labia majora return to their pre-arousal state in approximately 1 hour.[4]

Society and culture

In many cultures and locations all over the world, the labia, as part of the genitalia, are considered private, or intimate parts, whose exposure (especially in public) is governed by fairly strict socio-cultural mores. In many cases, public exposure is limited, and often prohibited by law.[9][10]

Views on pubic hair differ between people and between cultures. Some women prefer the look or feel of pubic hair, while others may choose to remove some or all of it. Temporary methods of removal include shaving, trimming, waxing, sugaring and depilatory products while permanent hair removal can be accomplished using electrolysis or laser hair removal.[11] In Korea, pubic hair is considered a sign of fertility, leading some women to have pubic hair transplants.[6]

Some women are self-conscious about the size, color or asymmetry of their labia. Viewing pornography may influence a woman's view of her genitals.[2][3] Models in pornography frequently have small or non-existent labia minora, and images are often airbrushed,[3][11] so pornographic images do not depict the full range of natural variations of the vulva. This can lead viewers of pornography to have unrealistic expectations about how the labia should look. Similar to how some women develop self-esteem issues from comparing their faces and bodies to airbrushed models in magazines, women who compare their vulvas to idealized pornographic images may believe their own labia are abnormal. This can have a negative impact on a woman's life, since genital self-consciousness makes it more difficult to enjoy sexual activity, see a gynecologist, or perform a genital self-examination.[3] Developing an awareness for how much the labia truly differ between individuals may help to overcome this self-consciousness.[11]

In several countries in Africa and Asia, the external female genitals are routinely altered or removed for reasons related to ideas about tradition, purity, hygiene and aesthetics. Known as female genital mutilation, the procedures include clitoridectomy and so-called "pharaonic circumcision," whereby the inner and outer labia are removed and the vulva is sewn shut.[12][13] FGM is mostly outlawed around the world, even in countries where the practice is widespread.[14]

Labiaplasty is a controversial plastic surgery procedure that involves the creation or reshaping of the labia.[15] Labia piercing is a cosmetic piercing, usually with a special needle under sterile conditions, of the inner or outer labia. Jewelry is worn in the resulting opening.

Additional images

Outer anatomy of clitoris.

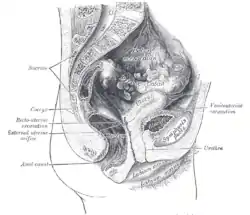

Outer anatomy of clitoris. Organs of the female reproductive system.

Organs of the female reproductive system. Median sagittal section of female pelvis.

Median sagittal section of female pelvis. Labia majora with pubic hair.

Labia majora with pubic hair.

See also

- Femalia

- Labia pride

- Labia stretching

- Labiaplasty

References

- Moore, Keith L.; Agur, Anne M. R.; Dalley II, Arthur F. (2010). Essential Clinical Anatomy, Fourth Edition. p. 268. ISBN 9781609131128.

- Farage, Miranda A.; Maibach, Howard I. (2006). The Vulva - Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. pp. 1–4, 14, 28–38. ISBN 978-0-8493-3608-9.

- Crooks, Robert; Baur, Karla (2014). Our Sexuality. Cengage Learning. pp. 50–54, 113–116, 163–171. ISBN 978-1-133-94336-5.

- Jones, Richard E.; Lopez, Kristin H. (2006). Human reproductive biology. Elsevier Science. pp. 55, 133–138, 154, 198–201. ISBN 9780080508368.

- Lloyd, Jillian; et al. (May 2005). "Female genital appearance: 'normality' unfolds" (PDF). British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 112 (5): 643–646. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.585.1427. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00517.x. PMID 15842291. S2CID 17818072.

- Carroll, Janell L. (2011). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. pp. 86–88, 116–120, 253–256. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3.

- Ginger, Van Anh T.; Yang, Claire C. (2011). "Functional Anatomy of the Female Sex Organs" in Cancer and Sexual Health (PDF). Humana Press. pp. 13–23.

- Lamanna, Mary Ann; Riedmann, Agnes (2011). Marriages, Families, and Relationships: Making Choices in a Diverse Society. Cengage Learning. pp. A7. ISBN 9781133172826.

- 617.23, Minnesota Statute

- 18-4116 — INDECENT EXPOSURE - Idaho 18-4116 — INDECENT EXPOSURE - Idaho Code :: Justia

- Herbenick, Debby; Schick, Vanessa (2011). Read My Lips: A Complete Guide to the Vagina & Vulva. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Inc. pp. 148–158, 165, 233–240. ISBN 978-1-4422-0802-5.

- "Classification of female genital mutilation", Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014.

- Gruenbaum, Emma (2001). The Female Circumcision Controversy: An Anthropological Perspective, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 2–3.

- Bonino, Emma (19 December 2012). "Banning Female Genital Mutilation", The New York Times.

- The Centrefold Project

External links

Media related to Labia (genitalia) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Labia (genitalia) at Wikimedia Commons

.png.webp)