Lordosis

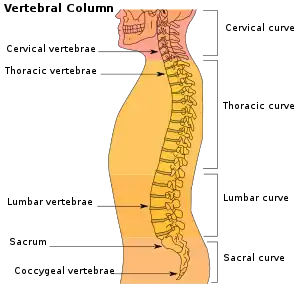

Lordosis is historically defined as an abnormal inward curvature of the lumbar spine.[1][2] However, the terms lordosis and lordotic are also used to refer to the normal inward curvature of the lumbar and cervical regions of the human spine.[3][4] Similarly, kyphosis historically refers to abnormal convex curvature of the spine. The normal outward (convex) curvature in the thoracic and sacral regions is also termed kyphosis or kyphotic. The term comes from the Greek lordōsis, from lordos ("bent backward").[5]

| Lordosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Diagram showing normal curvature (posterior concavity) of the cervical (neck) and lumbar (lower back) vertebral column (spine) | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, medical genetics |

| Diagnostic method | X-ray, MRI, CT Scan |

Lordosis in the human spine makes it easier for humans to bring the bulk of their mass over the pelvis. This allows for a much more efficient walking gait than that of other primates, whose inflexible spines cause them to resort to an inefficient forward leaning "bent-knee, bent-waist" gait. As such, lordosis in the human spine is considered one of the primary physiological adaptations of the human skeleton that allows for human gait to be as energetically efficient as it is.[6]

Lumbar hyperlordosis is excessive extension of the lumbar region, and is commonly called hollow back, sway back, or saddle back (after a similar condition that affects some horses). Lumbar kyphosis is an abnormally straight (or in severe cases flexed) lumbar region.

Types

Lumbar lordosis

Normal lordotic curvatures, also known as secondary curvatures, result in a difference in the thickness between the front and back parts of the intervertebral disc. Lordosis may also increase at puberty, sometimes not becoming evident until the early or mid-20s.

In radiology, a lordotic view is an X-ray taken of a patient leaning backward.[7]

Lumbar hyperlordosis

Lumbar hyperlordosis is a condition that occurs when the lumbar region (lower back) experiences stress or extra weight and is arched to point of muscle pain or spasms. Lumbar hyperlordosis is a common postural position where the natural curve of the lumbar region of the back is slightly or dramatically accentuated. Commonly known as swayback, it is common in dancers.[8] Imbalances in muscle strength and length are also a cause, such as weak hamstrings, or tight hip flexors (psoas). A major feature of lumbar hyperlordosis is a forward pelvic tilt, resulting in the pelvis resting on top of the thighs.

Other health conditions and disorders can cause hyperlordosis. Achondroplasia (a disorder where bones grow abnormally which can result in short stature as in dwarfism), Spondylolisthesis (a condition in which vertebrae slip forward) and osteoporosis (the most common bone disease in which bone density is lost resulting in bone weakness and increased likelihood of fracture) are some of the most common causes of hyperlordosis. Other causes include obesity, hyperkyphosis (spine curvature disorder in which the thoracic curvature is abnormally rounded), discitits (an inflammation of the intervertebral disc space caused by infection) and benign juvenile lordosis.[9] Other factors may also include those with rare diseases, as is the case with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS), where hyper-extensive and usually unstable joints (e.g. joints that are problematically much more flexible, frequently to the point of partial or full dislocation) are quite common throughout the body. With such hyper-extensibility, it is also quite common (if not the norm) to find the muscles surrounding the joints to be a major source of compensation when such instability exists.

Excessive lordotic curvature – lumbar hyperlordosis, is also called "hollow back", and "saddle back" (after a similar condition that affects some horses); swayback usually refers to a nearly opposite postural misalignment that can initially look quite similar.[10][11] Common causes of lumbar hyperlordosis include tight low back muscles, excessive visceral fat, and pregnancy. Rickets, a vitamin D deficiency in children, can cause lumbar hyperlordosis.

Lumbar hypolordosis

Being less common than lumbar hyperlordosis, hypolordosis (also known as flatback) occurs when there's less of a curve in the lower back or a flattening of the lower back. This occurs because the vertebrae are oriented toward the back of the spine, stretching the disc towards the back and compressing it in the front. This can cause a narrowing of the opening for the nerves, potentially pinching them.

Signs and symptoms

Lumbar hyperlordosis (also known as anterior pelvic tilt) has a noticeable impact on the height of individuals with this medical issue, a height loss of 0.5–2.5 inches (1.27–6.35 centimeters) is common.

For example, the height loss was measured by measuring the patient's height while he or she is standing straight (with exaggerated curves in the upper and lower back) and again after he or she fixed this issue (with no exaggerated curves), both of these measurements were taken in the morning with a gap of 6 months and the growth plates of the patient were checked to make sure that they were closed to rule out natural growth. The height loss occurs in the torso region and once the person fixes his or her back, the person's Body Mass Index will reduce since he or she is taller and the stomach will also appear to be slimmer.

A similar impact has also been noticed in transfeminine people who have weaker muscles in the lower back due to increased estrogen intake and other such treatments.

However, the cause of height loss in both situations is a little different even though the impact is similar. In the first scenario, it can be due to a genetic condition, trauma to the spine, pregnancy in women, increased abdominal fat or a sedentary lifestyle (sitting too much causes muscle imbalances and is the most common reason for this issue) and in the second scenario, the estrogen weakens the muscles in the area.

Merely slouching doesn't cause height loss even though it may make a person look shorter, slouching may lead to perceived height loss whereas lumbar hyperlordosis leads to actual and measured height loss. To make it easier to understand the difference, if a person loses a vertebra (which is around 2 inches or 5 centimeters in height) in his or her spine, it doesn't matter if he or she slouches or not, he or she will be shorter regardless of his or her posture. Lumbar hyperlordosis, of course, doesn't make you lose a vertebra but it bends them in such a way that your spine's vertical height is reduced.

Although lumbar hyperlordosis gives an impression of a stronger back, it can lead to moderate to severe lower back pain. The most problematic symptom is that of a herniated disc where the individual has put so much strain on the back that the discs between the vertebrae have been damaged or have ruptured. Technical problems with dancing such as difficulty in the positions of attitude and arabesque can be a sign of weak iliopsoas. Tightness of the iliopsoas results in a dancer having difficulty lifting their leg into high positions. Abdominal muscles being weak and the rectus femoris of the quadriceps being tight are signs that improper muscles are being worked while dancing which leads to lumbar hyperlordosis. The most obvious signs of lumbar hyperlordosis is lower back pain in dancing and pedestrian activities as well as having the appearance of a swayed back.[12]

Causes

Possible causes that lead to the condition of lumbar hyperlordosis are the following:

- Spines – Natural factors of how spines are formed greatly increase certain individuals' likelihood to experience a strain or sprain in their back or neck. Factors such as having more lumbar vertebrae allowing for too much flexibility, and then in cases of less lumbar the individual not reaching their necessity for flexibility and then pushing their bodies to injury.

- Legs – Another odd body formation is when an individual has a leg shorter than the other, which can be immediate cause for imbalance of hips then putting strain on the posture of the back which an individual has to adjust into vulnerable positions to meet aesthetic appearances. This can lead to permanent damage in the back. Genu recurvatum (sway back knees) is also a factor that forces a dancer to adjust into unstable postures.

- Hips – Common problems in the hips are tight hip flexors,[4] which causes for poor lifting posture, hip flexion contracture, which means the lack of postural awareness, and thoracic hyperkyphosis, which causes the individual to compensate for limited hip turn out (which is essential to dances such as ballet). Weak psoas (short for iliopsoas-muscle that controls the hip flexor) force the dancer to lift from strength of their back instead of from the hip when lifting their leg into arabesque or attitude. This causes great stress and risk of injury, especially because the dancer will have to compensate to obtain the positions required.

- Muscles – One of the greatest contributors is uneven muscles. Because all muscles have a muscle that works in opposition to it, it is imperative that to keep all muscles protected, the opposite muscle is not stronger than the muscle at risk. In the situation of lumbar lordosis, abdominal muscles are weaker than the muscles in the lumbar spine and the hamstring muscles. The muscular imbalance results in pulling down the pelvis in the front of the body, creating the swayback in the spine.[13]

- Growth spurt – Younger dancers are more at risk for development of lumbar hyperlordosis because the lumbar fascia and hamstrings tighten when a child starts to experience a growth spurt into adolescence.

Technical factors

- Improper lifts – When male dancers are performing dance lifts with another dancer they are extremely prone to lift in the incorrect posture, pushing their arms up to lift the other dancer, while letting their core and spine curve which is easy to then hyperlordosis in a dancer's back.

- Overuse – Over 45% of anatomical sites of injury in dancers are in the lower back. This can be attributed to the strains of repetitive dance training which may lead to minor trauma. If the damaged site is not given time to heal the damage of the injury will increase. Abrupt increases in dance intensity or sudden changes in dance choreography do not allow the body to adapt to the new stresses. New styles of dance, returning to dance, or increasing dance time by a great deal will result in exhaustion of the body.[14]

Diagnosis

Measurement and diagnosis of lumbar hyperlordosis can be difficult. Obliteration of vertebral end-plate landmarks by interbody fusion may make the traditional measurement of segmental lumbar lordosis more difficult. Because the L4–L5 and L5–S1 levels are most commonly involved in fusion procedures, or arthrodesis, and contribute to normal lumbar lordosis, it is helpful to identify a reproducible and accurate means of measuring segmental lordosis at these levels.[15][16] A visible sign of hyperlordosis is an abnormally large arch of the lower back and the person appears to be puffing out his or her stomach and buttocks.

X-ray

Precise diagnosis is done by looking at a complete medical history, physical examination and other tests of the patient. X-rays are used to measure the lumbar curvature. On a lateral X-ray, a normal range of the lordotic curvature of between 20° and 60° has been proposed by Stagnara et al., as measured from the inferior endplate of T12 to the inferior endplate of L5.[17] The Scoliosis Research Society has proposed a range of 40° and 60° as measured between the upper endplate of Th12 and the upper endplate of S1.[17] Individual studies, although using other reference points, have found normal ranges up to approximately 85°.[17] It is generally more pronounced in females.[17] It is relatively constant through adolescence and young adulthood, but decreases in the elderly.[17]

MRI and CT

Bone scans are conducted in order to rule out possible fractures and infections, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to eliminate the possibility of spinal cord or nerve abnormalities, and computed tomography scans (CT scans) are used to get a more detailed image of the bones, muscles and organs of the lumbar region.[18]

Treatment

Exercises

Some corrective exercises can be done to alleviate this issue, it may take several months to fix (provided that the person sits less, stands with a neutral pelvis and sleeps on their back).

Since lumbar hyperlordosis is usually caused by habitual poor posture, rather than by an inherent physical defect like scoliosis or hyperkyphosis, it can be reversed.[19] This can be accomplished by stretching the lower back, hip-flexors, quads and strengthening the abdominal muscles, hamstrings and glutes. Strengthening the gluteal complex is a commonly accepted practice to reverse excessive lumbar lordosis, as an increase in gluteals muscle tone assist in the reduction excessive anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar hyperlordosis.[20] Local intra-articular hip pain has been shown to inhibit gluteal contraction potential,[21] meaning that hip pain could be a main contributing factor to gluteal inhibition. Dancers should ensure that they don't strain themselves during dance rehearsals and performances. To help with lifts, the concept of isometric contraction, during which the length of muscle remains the same during contraction, is important for stability and posture.[22]

Lumbar hyperlordosis may be treated by strengthening the hip extensors on the back of the thighs, and by stretching the hip flexors on the front of the thighs.

Only the muscles on the front and on the back of the thighs can rotate the pelvis forward or backward while in a standing position because they can discharge the force on the ground through the legs and feet. Abdominal muscles and erector spinae can't discharge force on an anchor point while standing, unless one is holding his hands somewhere, hence their function will be to flex or extend the torso, not the hip. Back hyper-extensions on a Roman chair or inflatable ball will strengthen all the posterior chain and will treat hyperlordosis. So too will stiff legged deadlifts and supine hip lifts and any other similar movement strengthening the posterior chain without involving the hip flexors in the front of the thighs. Abdominal exercises could be avoided altogether if they stimulate too much the psoas and the other hip flexors.

Controversy regarding the degree to which manipulative therapy can help a patient still exists. If therapeutic measures reduce symptoms, but not the measurable degree of lordotic curvature, this could be viewed as a successful outcome of treatment, though based solely on subjective data. The presence of measurable abnormality does not automatically equate with a level of reported symptoms.[23]

Braces

The Boston brace is a plastic exterior that can be made with a small amount of lordosis to minimize stresses on discs that have experienced herniated discs. In the case where Ehlers Danlos syndrome (EDS) is responsible, being properly fitted with a customized brace may be a solution to avoid strain and limit the frequency of instability.

Tai chi

While not really a 'treatment', the art of tai chi chuan calls for adjusting the lower back curvature (as well as the rest of the spinal curvatures) through specific re-alignments of the pelvis to the thighs, it's referred to in shorthand as 'dropping the tailbone'. The specifics of the structural change are school specific, and are part of the jibengong (essential technique) of these schools. The adjustment is referred to in tai chi chuan literature as 'when the lowest vertebrae are plumb erect...'[24]

Footnotes

- Dorland, William (1965). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (24 ed.). Saunders. p. 851. ISBN 9780721631462.

- Stedman, Thomas (1976). Stedman's Medical Dictionary, Illustrated (23 ed.). Williams & Wilkins. p. 807. ISBN 0683079247.

- Medical Systems: A Body Systems Approach, 2005

- Simancek, Jeffrey A., ed. (2013-01-01), "Chapter 8 - Back and Abdominals", Deep Tissue Massage Treatment (Second Edition), St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 116–133, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-07759-0.00031-6, ISBN 978-0-323-07759-0, retrieved 2020-11-03

- "Lordosis". Wordnik. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- Lovejoy CO (2005). "The natural history of human gait and posture. Part 1. Spine and pelvis" (PDF). Gait & Posture. 21 (1): 95–112. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.01.001. PMID 15536039. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-21.

- "Lordotic Chest Technique".

- Solomon, Ruth. Preventing Dance Injuries: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, 1990. p. 85

- "Types of Spine Curvature Disorders". WebMD. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Sway back posture". lower-back-pain-management.com/. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- Cressey, Eric (2010-12-09). "Strategies for Correcting Bad Posture – Part 4". EricCressey.com. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- Solomon, Ruth. Preventing Dance Injuries: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, 1990. p. 122

- Howse, Justin. Dance Technique and Injury Prevention. Third Edition. London: A&C Black Limited, 2000. p. 193

- Brinson, Peter. Fit to Dance?. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 1996. p. 45

- Schuler Thomas C (Oct 2004). "Segmental Lumbar Lordosis: Manual Versus Computer-Assisted Measurement Using Seven Different Techniques". J Spinal Disord Tech. 17 (5): 372–79. doi:10.1097/01.bsd.0000109836.59382.47. PMID 15385876. S2CID 23503809.

- Subach Brian R (Oct 2004). "Segmental Lumbar Lordosis: Manual Versus Computer-Assisted Measurement Using Seven Different Techniques". J Spinal Disord Tech. 17 (5): 372–79. doi:10.1097/01.bsd.0000109836.59382.47. PMID 15385876. S2CID 23503809.

- p. 769 in: Norbert Boos, Max Aebi (2008). Spinal Disorders: Fundamentals of Diagnosis and Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3540690917.

- "Lordosis". Lucile Packard Children's Hospital.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - McKenzie, Robin (2011). Treat Your Own Back (Ninth ed.). New Zealand: Spinal Publications New Zealand, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9876504-0-5.

- Choi, Sil-ah (April 2015). "Isometric hip abduction using a Thera-Band alters gluteus maximus muscle activity and the anterior pelvic tilt angle during bridging exercise". Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 25 (2): 310–15. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2014.09.005. PMID 25262160.

- Freeman, Stephanie; Mascia, Anthony; McGill, Stuart (February 2013). "Arthrogenic neuromusculature inhibition: A foundational investigation of existence in the hip joint". Clinical Biomechanics. 28 (5): 171–77. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2012.11.014. PMID 23261019.

- Arnheim, Daniel D.. Dance Injuries:Their Prevention and Care. Second Edition. St. Louis, Missouri: C. V. Mosby Company, 1980. p. 36

- Harrison, DD; Jackson, BL; Troyanovich, S; Robertson, G; de George, D; Barker, WF (September 1994). "The efficacy of cervical extension-compression traction combined with diversified manipulation and drop table adjustments in the rehabilitation of cervical lordosis: a pilot study". Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 17 (7): 454–64. PMID 7989879.

- T'ai Chi Ch'uan: A Simplified Method of Calisthenics for Health & Self Defence. By Manqing Zheng p. 10

References

- Gabbey, Amber. "Lordosis". Healthline Networks Incorporated. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Gylys, Barbara A.; Mary Ellen Wedding (2005), Medical Terminology Systems, F.A. Davis Company

- "Osteoporosis-overview". A.D.A.M. Retrieved 8 December 2013.