Vacuum aspiration

Vacuum or suction aspiration is a procedure that uses a vacuum source to remove an embryo or fetus through the cervix. The procedure is performed to induce abortion, as a treatment for incomplete spontaneous abortion (otherwise commonly known as miscarriage) or retained fetal and placental tissue, or to obtain a sample of uterine lining (endometrial biopsy).[2][3] It is generally safe, and serious complications rarely occur.[4]

| Background | |

|---|---|

| Abortion type | Surgical |

| First use | China 1958 and UK 1967[1] |

| Gestation | 3-13+6 weeks |

| Usage | |

| Figures are combined usage of MVA and EVA. | |

| Sweden | 42.7% (2005) |

| UK: Eng. & Wales | 64% (2006) |

| United States | 59.9% (2016) |

| Infobox references | |

Some sources may use the terms dilation and evacuation[5] or "suction" dilation and curettage[6] to refer to vacuum aspiration, although those terms are normally used to refer to distinctly different procedures.

History

Vacuuming as a means of removing the uterine contents, rather than the previous use of a hard metal curette, was pioneered in 1958 by Drs Wu Yuantai and Wu Xianzhen in China,[7] but their paper was only translated into English on the fiftieth anniversary of the study which would ultimately pave the way for this procedure becoming exceedingly common. It is now known to be one of the safest obstetric procedures, and has saved countless lives.[1]

In Canada, the method was pioneered and improved on by Henry Morgentaler, achieving a complication rate of 0.48% and no deaths in over 5,000 cases.[8] He was the first doctor in North America to use the technique, which he then trained other doctors to use.[9]

Dorothea Kerslake introduced the method into the United Kingdom in 1967 and published a study in the United States that further spread the technique.[1][10]

Harvey Karman in the United States refined the technique in the early 1970s with the development of the Karman cannula, a soft, flexible cannula that avoided the need for initial cervical dilatation and so reduced the risks of puncturing the uterus.[1]

Clinical uses

Vacuum aspiration may be used as a method of induced abortion as well as a therapeutic procedure after spontaneous abortion. The procedure can also aid in regulation of the menstrual cycle and to obtain a sample for endometrial biopsy.[11] A study found use of Karman vacuum aspiration to be a safer option for endometrial biopsy when compared to the alternatives such as conventional endometrial curettage.[3] It is also used to terminate molar pregnancy.[12]

When used as a spontaneous abortion management or as a therapeutic abortion method, vacuum aspiration may be used alone or with cervical dilation anytime in the first trimester (up to 12 weeks gestational age). For more advanced pregnancies, vacuum aspiration may be used as one step in a dilation and evacuation procedure.[13] Vacuum aspiration is the surgical procedure used for almost all first-trimester abortions in many countries, if medication abortion is not a viable option .[11]

Procedure

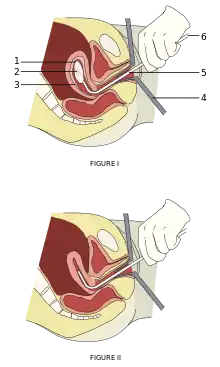

1: Amniotic sac

2: Embryo

3: Uterine lining

4: Speculum

5: Vacurette

6: Attached to a suction pump

Figure I is before aspiration of amniotic sac and embryo, and Figure II is after aspiration with the instrument still inside the uterus.

Vacuum aspiration is an outpatient procedure that generally involves a clinic visit of several hours.[14] The procedure itself typically takes less than 15 minutes.[15][16] Depending on the state of residence and local laws, two appointments and various other proceedings may be required if the vacuum aspiration is being used for therapeutic abortion.[17] There are two options for the source of suction in the use of these procedures. Suction can be created with either an electric pump (electric vacuum aspiration or EVA) or a manual pump (manual vacuum aspiration or MVA). A hand-held 25cc or 50cc syringe can function as a manual pump.[18] Both of these methods can create the same level of suction, and therefore are considered equivalent in terms of efficacy of treatment and safety.[19][20] The difference in use primarily comes down to provider preference.

The clinician places a speculum into the vagina in order to visualize the cervix. The cervix is cleansed, then a local anesthetic (usually lidocaine) is injected in the form of a para-cervical block or intra-cervical injection into the cervix.[21] The clinician may use instruments called "dilators" in incrementally larger sizes to gently open the cervix, or medically induce cervical dilation with drugs or osmotic dilators administered before the procedure.[22][23] Finally, a sterile cannula is inserted into the uterus. The cannula may be attached via tubing to the pump if using an electric vacuum, or attached directly to a syringe if using a manual vacuum aspirator. The pump creates a vacuum and suction which empties uterine contents, which either enter a canister or the syringe.[15]

After a procedure for abortion or miscarriage treatment, the tissue removed from the uterus is examined for completeness to ensure that no products of conception are left behind.[15] Expected contents include the embryo or fetus, as well as the decidua, chorionic villi, amniotic fluid, amniotic membrane and other tissues. These are all tissues which are found in a normal pregnancy. In the case of a molar pregnancy, these components will not be found.[24]

Post-treatment care includes brief observation in a recovery area and a follow-up appointment approximately two weeks later. During these visits, it is possible that the provider may perform tests to check for infection, as retained tissue in the uterus can be a source of infection.[25]

Additional medications used in vacuum aspiration include NSAID analgesics[26][21] that may be started the day before the procedure, as well as misoprostol the day before for cervical ripening which makes dilation of the cervix easier to perform.[27] Procedural sedation and analgesia may be offered to the patient in order to avoid discomfort.

Advantages over sharp dilation and curettage

Sharp dilation and curettage (D&C), also known as sharp curettage, was once the standard of care in situations requiring uterine evacuation. However, vacuum aspiration has a number of advantages over sharp D&C and has largely replaced D&C in many settings.[28] Manual vacuum aspiration has been found to have lower rates of incomplete evacuation and retained products of conception in the uterus.[29] Sharp curettage has also been associated with Asherman's Syndrome, whereas vacuum aspiration has not been found to have this longer term complication.[30] Overall, vacuum aspiration has been found to have lower rates of complications when compared to D&C.[19]

Vacuum aspiration may be used earlier in pregnancy when compared to sharp D&C. Manual vacuum aspiration is the only surgical abortion procedure available earlier than the sixth week of pregnancy.[15]

Vacuum aspiration, especially manual vacuum aspiration, is significantly cheaper than sharp D&C. The equipment needed for vacuum aspiration costs less than a set of surgical curettes. Additionally, sharp D&C is generally provided only by physicians, vacuum aspiration may be performed by advanced practice clinicians such as physician assistants and midwives, which greatly increases access to these services.[31]

Manual vacuum aspiration does not require electricity and so can be provided in locations that have unreliable electrical service or none at all. Manual vacuum aspiration also has the advantage of being quiet, without the louder noise of an electric vacuum pump, which can be stressful or bothersome to patients.[31]

Complications

When used for pregnancy evacuation, vacuum aspiration is 98% effective in removing all uterine contents.[19] One of the main complications is retained products of conception which will usually require a second aspiration procedure. This is more common when the procedure is performed very early in pregnancy, before 6 weeks gestational age.[15]

Another complication is infection, usually caused by retained products of conception or introduction of vaginal flora (otherwise known as bacteria) into the uterus. The rate of infection is 0.5%.[15]

Other complications occur at a rate of less than 1 per 100 procedures and include excessive blood loss, creating a hole through the cervix or uterus[19] (perforation) that may cause injury to other internal organs. Blood clots can possibly form within the uterus and block outflow of bleeding from the uterus which can cause the uterus to be enlarged and tender.[32]

References

- Coombes R (14 June 2008). "Obstetricians seek recognition for Chinese pioneers of safe abortion". BMJ. 336 (7657): 1332–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.39608.391030.DB. PMC 2427078. PMID 18556303.

- Sharma M (July 2015). "Manual vacuum aspiration: an outpatient alternative for surgical management of miscarriage". The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 17 (3): 157–161. doi:10.1111/tog.12198. ISSN 1467-2561. S2CID 116858777.

- Tansathit T, Chichareon S, Tocharoenvanich S, Dechsukhum C (October 2005). "Diagnostic evaluation of Karman endometrial aspiration in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 31 (5): 480–485. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2005.00324.x. ISSN 1341-8076. PMID 16176522. S2CID 20596711.

- Hemlin J, Möller B (2001-01-01). "Manual vacuum aspiration, a safe and effective alternative in early pregnancy termination". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 80 (6): 563–567. doi:10.1080/j.1600-0412.2001.080006563.x. ISSN 0001-6349. PMID 11380295.

- Wood D (January 2007). "Miscarriage". EBSCO Publishing Health Library. Brigham and Women's Hospital. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- "What Every Pregnant Woman Needs to Know About Pregnancy Loss and Neonatal Death". The Unofficial Guide to Having a Baby. WebMD. 2004-10-07. Archived from the original on 2007-10-21. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- Wu Y, Wu X (1958). "A report of 300 cases using vacuum aspiration for the termination of pregnancy". Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

- Morgentaler H (1973). "Report on 5641 outpatient abortions by vacuum suction curettage". CMAJ. 109 (12): 1202–5. PMC 1947080. PMID 4758593. Archived from the original on 2015-10-18.

- Morgentaler H (May–Jun 1989). "Alan F. Guttmacher lecture". Am J Gynecol Health. 3 (3–S): 38–45. PMID 12284999.

- Kerslake D, Casey D (July 1967). "Abortion induced by means of the uterine aspirator". Obstet Gynecol. 30 (1): 35–45. PMID 5338708.

- Baird TL, Flinn SK (2001). "Manual Vacuum Aspiration: Expanding women's access to safe abortions services" (PDF). Ipas: 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help), which cites:

- Greenslade F, Benson J, Winkler J, Henderson V, Leonard A (1993). "Summary of clinical and programmatic experience with manual vacuum aspiration". Advances in Abortion Care. 3 (2).

- "Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: A guide for doctors and midwives". World Health Organization. 2003. Archived from the original on 2006-09-09. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- Baird (2001), pp. 4-5,14 (sidebars and information box).

- Baird (2001), p. 10 (table).

- "Manual and vacuum aspiration for abortion". A-Z Health Guide from WebMD. October 2006. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2006.

- "What Happens During an In-Clinic Abortion?". www.plannedparenthood.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- "Texas Abortion Laws". www.plannedparenthood.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- "All About the Machine Vacuum Aspiration Procedure for Early Abortion". about.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Baird (2001), pp. 4-6.

- Goldberg AB, Dean G, Kang M, Youssof S, Darney PD (January 2004). "Manual versus electric vacuum aspiration for early first-trimester abortion: a controlled study of complication rates". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 103 (1): 101–107. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000109147.23082.25. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 14704252. S2CID 11374545.

- Allen RH, Singh R (June 2018). "Society of Family Planning clinical guidelines pain control in surgical abortion part 1 — local anesthesia and minimal sedation". Contraception. 97 (6): 471–477. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.014. PMID 29407363.

- Allen RH, Goldberg AB (2016-04-01). "Cervical dilation before first-trimester surgical abortion (<14 weeks' gestation)". Contraception. 93 (4): 277–291. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.001. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 26683499.

- Kapp N, Lohr PA, Ngo TD, Hayes JL (2010-02-17). "Cervical preparation for first trimester surgical abortion". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD007207. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007207.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 20166091.

- "Molar pregnancy - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- "FAQ: Post-Abortion Care and Recovery". ucsfhealth.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- Cansino C, Edelman A, Burke A, Jamshidi R (December 2009). "Paracervical Block With Combined Ketorolac and Lidocaine in First-Trimester Surgical Abortion: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 114 (6): 1220–1226. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c1a55b. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 19935022. S2CID 22458136.

- Table 2 in: Allison JL, Sherwood RS, Schust DJ (2011). "Management of first trimester pregnancy loss can be safely moved into the office". Rev Obstet Gynecol. 4 (1): 5–14. PMC 3100102. PMID 21629493.

- Baird (2001), p. 2.

- Mahomed K, Healy J, Tandon S (July 1994). "A comparison of manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) and sharp curettage in the management of incomplete abortion". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 46 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(94)90305-0. ISSN 0020-7292. PMID 7805979. S2CID 11606702.

- Barber AR, Rhone SA, Fluker MR (2014-11-01). "Curettage and Asherman's Syndrome—Lessons to (Re-) Learn?". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 36 (11): 997–1001. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30413-8. ISSN 1701-2163. PMID 25574677.

- Baird (2001), pp. 5,8-13.

- "Vacuum Aspiration for Abortion | Michigan Medicine". www.uofmhealth.org. Retrieved 2022-03-13.