Marchiafava–Bignami disease

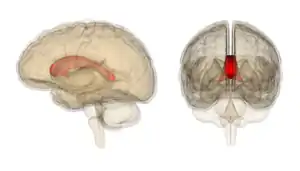

Marchiafava–Bignami disease is a progressive neurological disease of alcohol use disorder, characterized by corpus callosum demyelination and necrosis and subsequent atrophy. The disease was first described in 1903 by the Italian pathologists Amico Bignami and Ettore Marchiafava in an Italian Chianti drinker.[1][2] In this autopsy, Marchiafava and Bignami noticed that the middle two-thirds of the corpus callosum were necrotic. It is very difficult to diagnose and there is no specific treatment. Until 2008 only around 300 cases had been reported.[3] If caught early enough, most patients survive.

| Marchiafava–Bignami disease | |

|---|---|

| |

| This condition affects the corpus callosum | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Symptoms and signs

Symptoms can include, but are not limited to lack of consciousness, aggression, seizures, depression, hemiparesis, ataxia, apraxia, coma, etc.[4] There will also be lesions in the corpus callosum.

Causes

It is classically associated with chronic alcoholism especially with red wine consumption and sometimes associated nutritional deficiencies.[2] Alcohol use disorder can also cause thiamine deficiency, which is also observed to cause MBD.[5]

Mechanism

Individuals with MBD usually have a history of excessive alcohol consumption, but this is not always the case. The mechanism of the disease is not completely understood, but it is believed to be caused by a Vitamin B deficiency, malnutrition, or alcohol use disorder.[6] The damage to the brain can extend into neighboring white matter and sometimes go out as far as subcortical regions.[7]

Diagnosis

Marchiafava–Bignami disease is routinely diagnosed with the use of an MRI because the majority of clinical symptoms are non-specific. Before the use of such imaging equipment, it was unable to be diagnosed until autopsy. The patient usually has a history of alcohol use disorder or malnutrition and neurological symptoms are sometimes present and can help lead to a diagnosis. MBD can be told apart from other neural diseases due to the symmetry of the lesions in the corpus callosum as well as the fact that these lesions don't affect the upper and lower edges.[4]

There are two clinical subtypes of MBD

Type A- Stupor and coma predominate. Radiological imaging shows involvement of the entire corpus callosum. This type is also associated with symptoms of the upper motor neurons.[8]

Type B- This type has normal or only mildly impaired mental status and radiologic imaging shows partial lesions in the corpus callosum.[8]

Treatment

Treatment is variable depending on individuals. Some treatments work extremely well with some patients and not at all with others. Some treatments include therapy with thiamine and vitamin B complex. Alcohol consumption should be stopped. Some patients survive, but with residual brain damage and dementia. Others remain in comas that eventually lead to death. Nutritional counseling is also recommended.[4] Treatment is often similar to those administered for Wenicke-Korsakoff syndrome or for alcohol use disorder.[9]

Type A has 21% mortality rate and an 81% long-term disability rate. Type B has a 0% mortality rate and a 19% long-term disability rate.[8]

Recent Research

In a study published in 2015, a patient was observed to have MBD, but no history of excessive alcohol use. It is believed that he had protein, folic acid, and thiamine deficiencies, which are what caused the demyelination of the corpus callosum. The patient was diagnosed through MRI, but countless other neurological diseases needed to be ruled out initially.[6]

In a study published in 2016, a 45-year-old patient was observed to have taken high amounts of alcohol intake over 20 years and was malnourished. He was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. He was confused and had a lack of motor coordination. He also had altered sensorium and seizures. An MRI was performed and the patient was diagnosed with MBD.[9]

See also

References

- synd/2922 at Who Named It?

- E. Marchiafava, A. Bignami. Sopra un'alterazione del corpo calloso osservata da sogetti alcoolisti. Rivista di patologia nervosa e mentale, 1903, 8 (12): 544–549.

- "Marchiafava-Bignami Syndrome. MBD information". patient.info. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Raina, Sujeet & M Mahesh, D & Mahajan, J & S Kaushal, S & Gupta, D & Dhiman, Dalip. (2008). MarchiafavaBignami Disease. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 56. 633-5.

- Hillbom M, Saloheimo P, Fujioka S, Wszolek ZK, Juvela S, Leone MA. DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF MARCHIAFAVA-BIGNAMI DISEASE: A REVIEW OF CT/MRI CONFIRMED CASES. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):168-173. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2013-305979.

- YONGJIAN, C., LEI, Z., XIAOLI, W., WEIWEN, Z., DONGCAI, Y., & YAN, W. (2015). Marchiafava-Bignami disease with rare etiology: A case report. Experimental & Therapeutic Medicine, 9(4), 1515-1517. doi:10.3892/etm.2015.2263

- Arbelaez, Andres; Pajon, Adriana; Castillo, Mauricio (2003-11-01). "Acute Marchiafava-Bignami Disease: MR Findings in Two Patients". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 24 (10): 1955–1957. ISSN 0195-6108. PMC 8148934. PMID 14625216.

- "Marchiafava-Bignami Disease: Background, Etiology and Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 2017-07-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Parmanand H. T. Marchiafava–Bignami disease in chronic alcoholic patient. Radiology Case Reports. 2016;11(3):234-237. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2016.05.015.