Opsismodysplasia

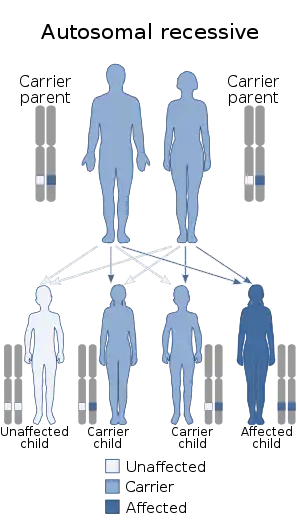

Opsismodysplasia is a type of skeletal dysplasia (a bone disease that interferes with bone development) first described by Zonana and associates in 1977, and designated under its current name by Maroteaux (1984). Derived from the Greek opsismos ("late"), the name "opsismodysplasia" describes a delay in bone maturation. In addition to this delay, the disorder is characterized by micromelia (short or undersized bones), particularly of the hands and feet, delay of ossification (bone cell formation), platyspondyly (flattened vertebrae), irregular metaphyses, an array of facial aberrations and respiratory distress related to chronic infection. Opsismodysplasia is congenital, being apparent at birth. It has a variable mortality, with some affected individuals living to adulthood. The disorder is rare, with an incidence of less than 1 per 1,000,000 worldwide. It is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means the defective (mutated) gene that causes the disorder is located on an autosome, and the disorder occurs when two copies of this defective gene are inherited. No specific gene has been found to be associated with the disorder. It is similar to spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, Sedaghatian type.[2][3][4][5][6]

| Opsismodysplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | OPSMD [1] |

| Specialty | Orthopedic |

Presentation

Opsismodysplasia can be characterized by a delay in bone maturation, which refers to "bone aging", an expected sequence of developmental changes in the skeleton corresponding to the chronological age of a person. Factors such as gender and ethnicity also play a role in bone age assessment. The only indicator of physical development that can be applied from birth through mature adulthood is bone age. Specifically, the age and maturity of bone can be determined by its state of ossification, the age-related process whereby certain cartilaginous and soft tissue structures are transformed into bone. The condition of epiphyseal plates (growth plates) at the ends of the long bones (which includes those of the arms, hands, legs and feet) is another measurement of bone age. The evaluation of both ossification and the state of growth plates in children is often reached through radiography (X-rays) of the carpals (bones of the hand and wrist).[7][8][9][10][11] In opsismodysplasia, the process of ossification in long bones can be disrupted by a failure of ossification centers (a center of organization in long bones, where cartilage cells designated to await and undergo ossification gather and align in rows)[12] to form. This was observed in a 16-month-old boy with the disorder, who had no apparent ossification centers in the carpals (bones of the hand and wrist) or tarsals (bones of the foot). This was associated with an absence of ossification in these bones, as well as disfigurement of the hands and feet at age two. The boy also had no ossification occurring in the lower femur (thigh bone) and upper tibia (the shin bone).[13]

Genetics

Opsismodysplasia is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.[5] This means the defective gene(s) responsible for the disorder is located on an autosome, and two copies of the defective gene (one inherited from each parent) are required in order to be born with the disorder. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder both carry one copy of the defective gene, but usually do not experience any signs or symptoms of the disorder. Currently, no specific mutation in any gene has been found to cause the disorder.[4][6]

It appears that the gene inositol polyphosphate phosphatase-like 1 is the cause of this condition in at least some cases.[14]

Diagnosis

Epidemiology

Opsismodysplasia is a very rare disorder, and is estimated to occur in less than 1 in 1,000,000 people.[6]

History

The disorder was first described by Jonathan Zonana and associates in 1977.[2] Further observation of four cases of it was reported by Pierre Maroteaux and colleagues in 1982,[15] and Maroteaux was the first to call the disorder "opsismodysplasia", in a 1984 journal report of three affected individuals.[3] The name derives from the Greek opsismos, meaning "late",[4] while the term dysplasia refers to development.[6]

References

- "OMIM Entry - # 258480 - OPSISMODYSPLASIA; OPSMD". omim.org. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- Zonana, J.; Rimoin, D.; Lachman, R.; Cohen, A. (1977). "A unique chondrodysplasia secondary to a defect in chondroosseous transformation". Birth Defects Original Article Series. 13 (3D): 155–163. PMID 922134.

- Maroteaux, P.; Stanescu, V.; Stanescu, R.; Le Marec, B.; Moraine, C.; Lejarraga, H. (Sep 1984). "Opsismodysplasia: A new type of chondrodysplasia with predominant involvement of the bones of the hand and the vertebrae". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 19 (1): 171–182. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320190117. PMID 6496568.

- Cormier-Daire, V.; Delezoide, A.; Philip, N.; Marcorelles, P.; Casas, K.; Hillion, Y.; Faivre, L.; Rimoin, D.; Munnich, A.; Maroteaux, P.; Le Merrer, M. (Mar 2003). "Clinical, radiological, and chondro-osseous findings in opsismodysplasia: Survey of a series of 12 unreported cases". Journal of Medical Genetics. 40 (3): 195–200. doi:10.1136/jmg.40.3.195. PMC 1735387. PMID 12624139.

- Tyler, K.; Sarioglu, N.; Kunze, J. (Mar 1999). "Five familial cases of opsismodysplasia substantiate the hypothesis of autosomal recessive inheritance". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 83 (1): 47–52. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19990305)83:1<47::AID-AJMG9>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID 10076884.

- "::Opsismodysplasia". Orphanet. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- Zerin, J.; Hernandez, R. (1991). "Approach to skeletal maturation". Hand Clinics. 7 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1016/S0749-0712(21)01310-X. PMID 2037639.

- Gilli, G. (1996). "The assessment of skeletal maturation". Hormone Research. 45 Suppl 2 (2): 49–52. doi:10.1159/000184847. PMID 8805044.

- Cox, L. (1997). "The biology of bone maturation and ageing". Acta Paediatrica. Supplement. 423: 107–108. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb18386.x. PMID 9401555. S2CID 42513080.

- Zhang, A.; Gertych, A.; Liu, B. (Jun–Jul 2007). "Automatic bone age assessment for young children from newborn to 7-year-old using carpal bones". Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 31 (4–5): 299–310. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2007.02.008. PMC 2041862. PMID 17369018.

- Gertych, A.; Zhang, A.; Sayre, J.; Pospiechkurkowska, S.; Huang, H. (Jun–Jul 2007). "Bone age assessment of children using a digital hand atlas". Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 31 (4–5): 322–331. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2007.02.012. PMC 1978493. PMID 17387000.

- Gray, Henry; Spitzka, Edward Anthony (1910). Anatomy, descriptive and applied. the University of California: Lea & Febiger. p. 44.

ossification.

- Beemer, F. A.; Kozlowski, K. S. (Feb 1994). "Additional case of opsismodysplasia supporting autosomal recessive inheritance". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 49 (3): 344–347. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320490321. PMID 8209898.

- Chai EC, Singaraja RR (2013) Opsismodysplasia: Implications of mutations in the developmental gene INPPL1. Clin Genet doi: 10.1111/cge.12136

- Maroteaux, P.; Stanescu, V.; Stanescu, R. (1982). "Four recently described osteochondrodysplasias". Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 104: 345–350. PMID 7163279.