Influenza pandemic

An influenza pandemic is an epidemic of an influenza virus that spreads across a large region (either multiple continents or worldwide) and infects a large proportion of the population. There have been six major influenza epidemics in the last 140 years, with the 1918 flu pandemic being the most severe; this is estimated to have been responsible for the deaths of 50–100 million people. The most recent, the 2009 swine flu pandemic, resulted in under 300,000 deaths and is considered relatively mild. These pandemics occur irregularly.

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

Influenza pandemics occur when a new strain of the influenza virus is transmitted to humans from another animal species. Species that are thought to be important in the emergence of new human strains are pigs, chickens and ducks. These novel strains are unaffected by any immunity people may have to older strains of human influenza and can therefore spread extremely rapidly and infect very large numbers of people. Influenza A viruses can occasionally be transmitted from wild birds to other species, causing outbreaks in domestic poultry, and may give rise to human influenza pandemics.[1][2] The propagation of influenza viruses throughout the world is thought in part to be by bird migrations, though commercial shipments of live bird products might also be implicated, as well as human travel patterns.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has produced a six-stage classification that describes the process by which a novel influenza virus moves from the first few infections in humans through to a pandemic. This starts with the virus mostly infecting animals, with a few cases where animals infect people, then moves through the stage where the virus begins to spread directly between people, and ends with a pandemic when infections from the new virus have spread worldwide.[3]

One strain of virus that may produce a pandemic in the future is a highly pathogenic variation of the H5N1 subtype of influenza A virus. On 11 June 2009, a new strain of H1N1 influenza was declared to be a pandemic (Stage 6) by the WHO after evidence of spreading in the southern hemisphere.[4] The 13 November 2009 worldwide update by the WHO stated that "[a]s of 8 November 2009, worldwide more than 206 countries and overseas territories or communities have reported [503,536] laboratory confirmed cases of pandemic influenza H1N1 2009, including over 6,250 deaths."[5]

Influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease of birds and mammals. It was thought to be caused by comets, earthquakes, volcanoes, cosmic dust, the rising and setting of the sun, vapors arising from the air and ground, or a blast from the stars.[6] Now we know that it is caused by an RNA virus of the family Orthomyxoviridae (the influenza viruses). In humans, common symptoms of influenza infection are fever, sore throat, muscle pains, severe headache, coughing, and weakness and fatigue.[7] In more serious cases, influenza causes pneumonia, which can be fatal, particularly in young children and the elderly. While sometimes confused with the common cold, influenza is a much more severe disease and is caused by a different type of virus.[8] Although nausea and vomiting can be produced, especially in children,[7] these symptoms are more characteristic of the unrelated gastroenteritis, which is sometimes called "stomach flu" or "24-hour flu."[9]

Typically, influenza is transmitted from infected mammals through the air by coughs or sneezes, creating aerosols containing the virus, and from infected birds through their droppings. Influenza can also be transmitted by saliva, nasal secretions, feces, and blood. Healthy individuals can become infected if they breathe in a virus-laden aerosol directly, or if they touch their eyes, nose or mouth after touching any of the aforementioned bodily fluids (or surfaces contaminated with those fluids). Flu viruses can remain infectious for about one week at human body temperature, over 30 days at 0 °C (32 °F), and indefinitely at very low temperatures (such as lakes in northeast Siberia). Most influenza strains can be inactivated easily by disinfectants and detergents.[10][11][12]

Flu spreads around the world in seasonal epidemics. Ten pandemics were recorded before the Spanish flu of 1918.[6] Three influenza pandemics occurred during the 20th century and killed tens of millions of people, with each of these pandemics being caused by the appearance of a new strain of the virus in humans. Often, these new strains result from the spread of an existing flu virus to humans from other animal species, so close proximity between humans and animals can promote epidemics. In addition, epidemiological factors, such as the WWI practice of packing soldiers with severe influenza illness into field hospitals while soldiers with mild illness stayed outside on the battlefield, are an important determinant of whether or not a new strain of influenza virus will spur a pandemic.[13] (During the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, this practice served to promote the evolution of more virulent viral strains over those that produced mild illness.) When it first killed humans in Asia in the 1990s, a deadly avian strain of H5N1 posed a great risk for a new influenza pandemic; however, this virus did not mutate to spread easily between people.[14]

Vaccinations against influenza are most commonly given to high-risk humans in industrialized countries[15] and to farmed poultry.[16] The most common human vaccine is the trivalent influenza vaccine that contains purified and inactivated material from three viral strains. Typically this vaccine includes material from two influenza A virus subtypes and one influenza B virus strain.[17] A vaccine formulated for one year may be ineffective in the following year, since the influenza virus changes rapidly over time and different strains become dominant. Antiviral drugs can be used to treat influenza, with neuraminidase inhibitors being particularly effective.

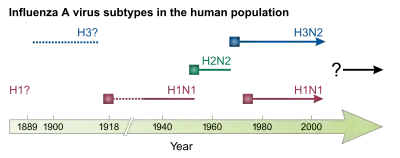

Variants and subtypes of Influenza A virus

Variants of Influenza A virus are identified and named according to the isolate that they are like and thus are presumed to share lineage (example Fujian flu virus like); according to their typical host (example Human flu virus); according to their subtype (example H3N2); and according to their deadliness (e.g., Low Pathogenic as discussed below). So, a flu from a virus similar to the isolate A/Fujian/411/2002(H3N2) is called Fujian flu, human flu, and H3N2 flu.

Variants are sometimes named according to the species (host) the strain is endemic in or adapted to. Some variants named using this convention are:[19]

Avian variants have also sometimes been named according to their deadliness in poultry, especially chickens:

- Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI)

- Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), also called: deadly flu or death flu

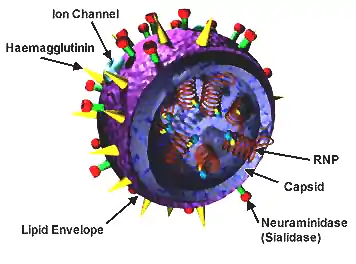

The Influenza A virus subtypes are labeled according to an H number (for hemagglutinin) and an N number (for neuraminidase). Each subtype virus has mutated into a variety of strains with differing pathogenic profiles; some pathogenic to one species but not others, some pathogenic to multiple species. Most known strains are extinct strains. For example, the annual flu subtype H3N2 no longer contains the strain that caused the Hong Kong flu.[20]

Influenza A viruses are negative sense, single-stranded, segmented RNA viruses. "There are 16 different HA antigens (H1 to H16) and nine different NA antigens (N1 to N9) for influenza A. Until recently, 15 HA types had been recognized, but recently two new types were isolated: a new type (H16) was isolated from black-headed gulls caught in Sweden and the Netherlands in 1999 and reported in the literature in 2005."[21] "The other, H17, was isolated from fruit bats caught in Guatemala and reported in the literature in 2013."[22]

Nature of a flu pandemic

Some pandemics are relatively minor such as the one in 1957 called Asian flu (1–4 million dead, depending on source). Others have a higher Pandemic Severity Index whose severity warrants more comprehensive social isolation measures.[23]

The 1918 pandemic killed tens of millions and sickened hundreds of millions; the loss of this many people in the population caused upheaval and psychological damage to many people.[24] There were not enough doctors, hospital rooms, or medical supplies for the living as they contracted the disease. Dead bodies were often left unburied as few people were available to deal with them. There can be great social disruption as well as a sense of fear. Efforts to deal with pandemics can leave a great deal to be desired because of human selfishness, lack of trust, illegal behavior, and ignorance. For example, in the 1918 pandemic: "This horrific disconnect between reassurances and reality destroyed the credibility of those in authority. People felt they had no one to turn to, no one to rely on, no one to trust."[25]

A letter from a physician at one U.S. Army camp in the 1918 pandemic said:

It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes [...]. It is horrible. One can stand it to see one, two or twenty men die, but to see these poor devils dropping like flies [...]. We have been averaging about 100 deaths per day [...]. Pneumonia means in about all cases death [...]. We have lost an outrageous number of Nurses and Drs. It takes special trains to carry away the dead. For several days there were no coffins and the bodies piled up something fierce [...].[26]

Wave nature

Flu pandemics typically come in waves. The 1889–1890 and 1918–1920 flu pandemics each came in three or four waves of increasing lethality.[27] But within a wave, mortality was greater at the beginning of the wave.[28]

Variable mortality

Mortality varies widely in a pandemic. In the 1918 pandemic:

In U.S. Army camps where reasonably reliable statistics were kept, case mortality often exceeded 5 percent, and in some circumstances exceeded 10 percent. In the British Army in India, case mortality for white troops was 9.6 percent, for Indian troops 21.9 percent. In isolated human populations, the virus killed at even higher rates. In the Fiji islands, it killed 14 percent of the entire population in 16 days. In Labrador and Alaska, it killed at least one-third of the entire native population.[29]

Influenza pandemics

A 1921 book lists nine influenza pandemics prior to the 1889–1890 flu, the first in 1510.[6] A more modern source lists six.[30]

| Name | Date | World pop. | Subtype | Reproduction number[33] | Infected (est.) | Deaths worldwide | Case fatality rate | Pandemic severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889–1890 pandemic[34] | 1889–90 | 1.53 billion | Likely H3N8 or H2N2 | 2.10 (IQR, 1.9–2.4)[34] | 20–60%[34] (300–900 million) | 1 million | 0.10–0.28%[34] | 2 |

| Spanish flu[35] | 1918–20 | 1.80 billion | H1N1 | 1.80 (IQR, 1.47–2.27) | 33% (500 million)[36] or >56% (>1 billion)[37] | 17[38]–100[39][40] million | 2–3%,[37] or ~4%, or ~10%[41] | 5 |

| Asian flu | 1957–58 | 2.90 billion | H2N2 | 1.65 (IQR, 1.53–1.70) | >17% (>500 million)[37] | 1–4 million[37] | <0.2%[37] | 2 |

| Hong Kong flu | 1968–69 | 3.53 billion | H3N2 | 1.80 (IQR, 1.56–1.85) | >14% (>500 million)[37] | 1–4 million[37] | <0.2%[37][42] | 2 |

| 1977 Russian flu | 1977–79 | 4.21 billion | H1N1 | ? | ? | 0.7 million[43] | ? | ? |

| 2009 swine flu pandemic[44][45] | 2009–10 | 6.85 billion | H1N1/09 | 1.46 (IQR, 1.30–1.70) | 11–21% (0.7–1.4 billion)[46] | 151,700–575,400[47] | 0.01%[48][49] | 1 |

| Typical seasonal flu[t 1] | Every year | 7.75 billion | A/H3N2, A/H1N1, B, ... | 1.28 (IQR, 1.19–1.37) | 5–15% (340 million – 1 billion)[50] 3–11% or 5–20%[51][52] (240 million – 1.6 billion) |

290,000–650,000/year[53] | <0.1%[54] | 1 |

Notes

| ||||||||

Asiatic flu (1889–1890)

The 1889–1890 pandemic, often referred to as the Asiatic flu[55] or Russian flu, killed about 1 million people[56][57] out of a world population of about 1.5 billion.

It was the last great pandemic of the 19th century, and is among the deadliest pandemics in history.[58][59] The most reported effects of the pandemic took place from October 1889 to December 1890, with recurrences in 1891 to 1895.

Spanish flu (1918–1920)

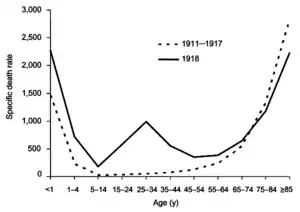

The 1918 flu pandemic, commonly referred to as the Spanish flu, was a category 5 influenza pandemic caused by an unusually severe and deadly Influenza A virus strain of subtype H1N1.

The Spanish flu pandemic lasted from 1918 to 1920.[61] Various estimates say it killed between 17 million and 100 million people[62][27][63] This pandemic has been described as "the greatest medical holocaust in history" and may have killed as many people as the Black Death,[64] although the Black Death is estimated to have killed over a fifth of the world's population at the time,[65] a significantly higher proportion. This huge death toll was caused by an extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by cytokine storms.[62] Indeed, symptoms in 1918 were so unusual that initially influenza was misdiagnosed as dengue, cholera, or typhoid. One observer wrote, "One of the most striking of the complications was hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred."[27] The majority of deaths were from bacterial pneumonia, a secondary infection caused by influenza, but the virus also killed people directly, causing massive hemorrhages and edema in the lung.[66]

The Spanish flu pandemic was truly global, spreading even to the Arctic and remote Pacific islands. The unusually severe disease killed between 10 and 20% of those infected, as opposed to the more usual flu epidemic mortality rate of 0.1%.[27][60] Another unusual feature of this pandemic was that it mostly killed young adults, with 99% of pandemic influenza deaths occurring in people under 65, and more than half in young adults 20 to 40 years old.[67] This is unusual since influenza is normally most deadly to the very young (under age 2) and the very old (over age 70). The total mortality of the 1918–1920 pandemic is estimated to be between 17 and 100 million people, constituting approximately 1–6% of the world's population. As many as 25 million may have been killed in the first 25 weeks; in contrast, HIV/AIDS has killed 25 million in its first 25 years.[27]

Asian flu (1957–1958)

The Asian flu was a category 2 flu pandemic outbreak caused by a strain of H2N2 that originated in China in early 1957, lasting until 1958. The virus originated from a mutation in wild ducks combining with a pre-existing human strain.[68] The virus was first identified in Guizhou in late February; by mid-March it had spread across the entire mainland.[69] It was not until the virus had reached Hong Kong in April, however, that the world was alerted to the unusual situation, when the international press began to report on the outbreak.[70] The World Health Organization was officially informed when the virus arrived in Singapore, which operated the only influenza surveillance laboratory in Southeast Asia,[71] in early May.[72] From that point on, as the virus continued to sweep the region, the WHO remained attuned to the developing outbreak and helped coordinate the global response for the duration of the pandemic.[73]

This was the first pandemic to occur during what is considered the "era of modern virology".[74] One significant development since the 1918 pandemic was the identification of the causative agent behind the flu.[75] Later, it was recognized that the influenza virus changes over time, typically only slightly (a process called "antigenic drift"), sometimes significantly enough to result in a new subtype ("antigenic shift").[76] Within weeks of the report out of Hong Kong, laboratories in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia had analyzed the virus and concluded that it was a novel strain of influenza A.[77] Chinese researchers had already come to a similar conclusion in March,[77] but as China was not a member of the WHO nor a part of its network of National Influenza Centers, this information did not reach the rest of the world, a fact which the WHO would lament after the pandemic.[73]

The virus swept across the Middle East, Africa, and the Southern Hemisphere in the middle months of the year, causing widespread outbreaks. By the end of September, nearly the entire inhabited world had been infected or at least seeded with the virus.[77] Around this time, extensive epidemics developed in the Northern Hemisphere following the opening of schools, generally peaking in North America and Europe in October.[78] Some countries experienced a second wave in the final months of the year; Japan experienced a particularly severe resurgence in October.[77][78] Influenza activity had largely subsided by the end of the year and remained apparently low during the first months of 1958, though some countries, such as the United States, experienced another rise in mortality from respiratory disease, of unclear origin.[77]

The disease tended to resemble seasonal influenza in its presentation; the WHO described it at the time as "uniformly benign".[77][73] However, there was the potential for complications, of which there was some variability.[79] Most deaths were a result of bacterial pneumonia, though cases of this condition were attenuated through the use of antibiotics that did not exist in 1918.[77][80] There were also detailed accounts of fatal primary influenza pneumonia, with no indication of bacterial infection.[80] Those with underlying conditions such as cardiovascular disease were at greater risk of developing these pneumonias; pregnant women were also vulnerable to complications.[81][80] In general, the elderly experienced the greatest rates of mortality.[81] Estimates of worldwide deaths vary widely depending on the source, ranging from 1 million to 4 million.[82] Mortality in the US has been estimated between 60,000 and 80,000 deaths.[83][84][85][81] Pandemic impact continued over several years in many countries, with Latin America experiencing considerable excess mortality through 1959.[86] Chile experienced notably severe mortality over the course of two waves during this period.[87]

This was the most publicized influenza epidemic at the time of its occurrence.[88] As the first pandemic to occur in the context of a global surveillance network, it was also the first time that preparations could be made ahead of an anticipated epidemic.[77][89] Vaccination efforts were undertaken in some countries such as the US, though it is doubtful how successful such campaigns were with altering the courses of individual epidemics, mainly due to the timing of when the vaccines became widely available and how many people were able to be effectively immunized before the peak.[73][90]

Hong Kong flu (1968–1970)

The Hong Kong flu was a category 2 flu pandemic caused by a strain of H3N2 descended from H2N2 by antigenic shift, in which genes from multiple subtypes reassorted to form a new virus. This pandemic killed an estimated 1–4 million people worldwide.[82][91][92] Those over 65 had the greatest death rates.[93] In the US, there were about 100,000 deaths.[94]

Russian flu (1977–1979)

The 1977 Russian flu was a relatively benign flu pandemic, mostly affecting population younger than the age of 26 or 25.[95][96] It is estimated that 700,000 people died due to the pandemic worldwide.[97] The cause was H1N1 virus strain, which was not seen after 1957 until its re-appearance in China and the Soviet Union in 1977.[98][96][99] Genetic analysis and several unusual characteristics of the pandemic have prompted speculation that the virus was released to the public through a laboratory accident.[96][100][101][102][103]

H1N1/09 flu pandemic (2009–2010)

An epidemic of influenza-like illness of unknown causation occurred in Mexico in March–April 2009. On 24 April 2009, following the isolation of an A/H1N1 influenza in seven ill patients in the southwest US, the WHO issued a statement on the outbreak of "influenza like illness" that confirmed cases of A/H1N1 influenza had been reported in Mexico, and that 20 confirmed cases of the disease had been reported in the US. The next day, the number of confirmed cases rose to 40 in the US, 26 in Mexico, six in Canada, and one in Spain. The disease spread rapidly through the rest of the spring, and by 3 May, a total of 787 confirmed cases had been reported worldwide.[104]

On 11 June 2009, the ongoing outbreak of Influenza A/H1N1, commonly referred to as swine flu, was officially declared by the WHO to be the first influenza pandemic of the 21st century and a new strain of Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 first identified in April 2009.[105] It is thought to be a mutation (reassortment) of four known strains of influenza A virus subtype H1N1: one endemic in humans, one endemic in birds, and two endemic in pigs (swine).[106] The rapid spread of this new virus was likely due to a general lack of pre-existing antibody-mediated immunity in the human population.[107]

On 1 November 2009, a worldwide update by the WHO stated that "199 countries and overseas territories/communities have officially reported a total of over 482,300 laboratory confirmed cases of the influenza pandemic H1N1 infection, that included 6,071 deaths."[108] By the end of the pandemic, declared on 10 August 2010, there were more than 18,000 laboratory-confirmed deaths from H1N1.[109] Due to inadequate surveillance and lack of healthcare in many countries, the actual total of cases and deaths was likely much higher than reported. Experts, including the WHO, have since agreed that an estimated 284,500 people were killed by the disease, about 15 times the number of deaths in the initial death toll.[110][111]

Other pandemic threat subtypes

"Human influenza virus" usually refers to those subtypes that spread widely among humans. H1N1, H1N2, and H3N2 are the only known Influenza A virus subtypes currently circulating among humans.[112]

Genetic factors in distinguishing between "human flu viruses" and "avian influenza viruses" include:

- PB2: (RNA polymerase): Amino acid (or residue) position 627 in the PB2 protein encoded by the PB2 RNA gene. Until H5N1, all known avian influenza viruses had a glutamic acid at position 627, while all human influenza viruses had a lysine.

- HA: (hemagglutinin): Avian influenza HA bind alpha 2–3 sialic acid receptors while human influenza HA bind alpha 2–6 sialic acid receptors.

"About 52 key genetic changes distinguish avian influenza strains from those that spread easily among people, according to researchers in Taiwan, who analyzed the genes of more than 400 A type flu viruses."[113] "How many mutations would make an avian virus capable of infecting humans efficiently, or how many mutations would render an influenza virus a pandemic strain, is difficult to predict. We have examined sequences from the 1918 strain, which is the only pandemic influenza virus that could be entirely derived from avian strains. Of the 52 species-associated positions, 16 have residues typical for human strains; the others remained as avian signatures. The result supports the hypothesis that the 1918 pandemic virus is more closely related to the avian influenza A virus than are other human influenza viruses."[114]

Highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza kills 50% of humans that catch it. In one case, a boy with H5N1 experienced diarrhea followed rapidly by a coma without developing respiratory or flu-like symptoms.[115]

The Influenza A virus subtypes that have been confirmed in humans, ordered by the number of known human pandemic deaths, are:

- H1N1 caused Spanish flu, 1977 Russian flu, and the 2009 swine flu pandemic (novel H1N1)

- H2N2 caused Asian flu

- H3N2 caused Hong Kong flu

- H5N1 is bird flu, endemic in avians

- H7N7 has unusual zoonotic potential

- H1N2 is currently endemic in humans and pigs

- H9N2, H7N2, H7N3, H10N7

- H1N1

| External images | |

|---|---|

H1N1 is currently endemic in both human and pig populations. A variant of H1N1 was responsible for the Spanish flu pandemic that killed some 50 million to 100 million people worldwide over about a year in 1918 and 1919.[116] Controversy arose in October 2005, after the H1N1 genome was published in the journal, Science. Many fear that this information could be used for bioterrorism.[117]

When he compared the 1918 virus with today's human flu viruses, Dr. Taubenberger noticed that it had alterations in just 25 to 30 of the virus's 4,400 amino acids. Those few changes turned a bird virus into a killer that could spread from person to person.[118]

In mid-April 2009, an H1N1 variant appeared in Mexico, with its center in Mexico City. By 26 April the variant had spread widely; with cases reported in Canada, the US, New Zealand, the UK, France, Spain and Israel. On 29 April the WHO raised the worldwide pandemic phase to 5.[119] On 11 June 2009 the WHO raised the worldwide pandemic phase to 6, which means that the H1N1 swine flu has reached pandemic proportions, with nearly 30,000 confirmed cases worldwide.[120] A 13 November 2009 worldwide update by the WHO states that "206 countries and overseas territories/communities have officially reported over 503,536 laboratory confirmed cases of the influenza pandemic H1N1 infection, including 6,250 deaths."[121]

- H2N2

The Asian Flu was a pandemic outbreak of H2N2 avian influenza that originated in China in 1957, spread worldwide that same year during which an influenza vaccine was developed, lasted until 1958 and caused between one and four million deaths.

- H3N2

H3N2 is currently endemic in both human and pig populations. It evolved from H2N2 by antigenic shift and caused the Hong Kong flu pandemic that killed up to 750,000.[122]"An early-onset, severe form of influenza A H3N2 made headlines when it claimed the lives of several children in the United States in late 2003."[123]

The dominant strain of annual flu in January 2006 is H3N2. Measured resistance to the standard antiviral drugs amantadine and rimantadine in H3N2 has increased from 1% in 1994 to 12% in 2003 to 91% in 2005.[124]

[C]ontemporary human H3N2 influenza viruses are now endemic in pigs in southern China and can reassort with avian H5N1 viruses in this intermediate host.[125]

- H7N7

H7N7 has unusual zoonotic potential. In 2003 in Netherlands 89 people were confirmed to have H7N7 influenza virus infection following an outbreak in poultry on several farms. One death was recorded.

- H1N2

H1N2 is currently endemic in both human and pig populations. The new H1N2 strain appears to have resulted from the reassortment of the genes of the currently circulating influenza H1N1 and H3N2 subtypes. The hemagglutinin protein of the H1N2 virus is similar to that of the currently circulating H1N1 viruses and the neuraminidase protein is similar to that of the current H3N2 viruses.

Assessment of a flu pandemic

Stages

| WHO Pandemic Influenza Phases (2009)[126][127] | |

|---|---|

| Phase | Description |

| Phase 1 | No animal influenza virus circulating among animals have been reported to cause infection in humans. |

| Phase 2 | An animal influenza virus circulating in domesticated or wild animals is known to have caused infection in humans and is therefore considered a specific potential pandemic threat. |

| Phase 3 | An animal or human-animal influenza reassortant virus has caused sporadic cases or small clusters of disease in people, but has not resulted in human-to-human transmission sufficient to sustain community-level outbreaks. |

| Phase 4 | Human to human transmission of an animal or human-animal influenza reassortant virus able to sustain community-level outbreaks has been verified. |

| Phase 5 | Human-to-human spread of the virus in two or more countries in one WHO region. |

| Phase 6 | In addition to the criteria defined in Phase 5, the same virus spreads from human-to-human in at least one other country in another WHO region. |

| Post peak period | Levels of pandemic influenza in most countries with adequate surveillance have dropped below peak levels. |

| Post pandemic period | Levels of influenza activity have returned to the levels seen for seasonal influenza in most countries with adequate surveillance. |

The World Health Organization (WHO) developed a global influenza preparedness plan, which defines the stages of a pandemic, outlines WHO's role and makes recommendations for national measures before and during a pandemic.[128]

In the 2009 revision of the phase descriptions, the WHO has retained the use of a six-phase approach for easy incorporation of new recommendations and approaches into existing national preparedness and response plans. The grouping and description of pandemic phases have been revised to make them easier to understand, more precise, and based upon observable phenomena. Phases 1–3 correlate with preparedness, including capacity development and response planning activities, while phases 4–6 clearly signal the need for response and mitigation efforts. Furthermore, periods after the first pandemic wave are elaborated to facilitate post pandemic recovery activities.

In February 2020, WHO spokesperson Tarik Jasarevic explained that the WHO no longer uses this six-phase classification model: "For the sake of clarification, WHO does not use the old system of 6 phases—that ranged from phase 1 (no reports of animal influenza causing human infections) to phase 6 (a pandemic)—that some people may be familiar with from H1N1 in 2009."[129]

For reference, the phases are defined below.[130]

In nature, influenza viruses circulate continuously among animals, especially birds. Even though such viruses might theoretically develop into pandemic viruses, in Phase 1 no viruses circulating among animals have been reported to cause infections in humans.

In Phase 2 an animal influenza virus circulating among domesticated or wild animals is known to have caused infection in humans, and is therefore considered a potential pandemic threat.

In Phase 3, an animal or human-animal influenza reassortant virus has caused sporadic cases or small clusters of disease in people, but has not resulted in human-to-human transmission sufficient to sustain community-level outbreaks. Limited human-to-human transmission may occur under some circumstances, for example, when there is close contact between an infected person and an unprotected caregiver. However, limited transmission under such restricted circumstances does not indicate that the virus has gained the level of transmissibility among humans necessary to cause a pandemic.

Phase 4 is characterized by verified human-to-human transmission of an animal or human-animal influenza reassortant virus able to cause "community-level outbreaks". The ability to cause sustained disease outbreaks in a community marks a significant upwards shift in the risk for a pandemic. Any country that suspects or has verified such an event should urgently consult with the WHO so that the situation can be jointly assessed and a decision made by the affected country if implementation of a rapid pandemic containment operation is warranted. Phase 4 indicates a significant increase in risk of a pandemic but does not necessarily mean that a pandemic is a foregone conclusion.

Phase 5 is characterized by human-to-human spread of the virus into at least two countries in one WHO region. While most countries will not be affected at this stage, the declaration of Phase 5 is a strong signal that a pandemic is imminent and that the time to finalize the organization, communication, and implementation of the planned mitigation measures is short.

Phase 6, the pandemic phase, is characterized by community level outbreaks in at least one other country in a different WHO region in addition to the criteria defined in Phase 5. Designation of this phase will indicate that a pandemic is under way.

During the post-peak period, pandemic disease levels in most countries with adequate surveillance will have dropped below peak observed levels. The post-peak period signifies that pandemic activity appears to be decreasing; however, it is uncertain if additional waves will occur and countries will need to be prepared for a second wave.

Previous pandemics have been characterized by waves of activity spread over months. Once the level of disease activity drops, a critical communications task will be to balance this information with the possibility of another wave. Pandemic waves can be separated by months and an immediate "at-ease" signal may be premature.

In the post-pandemic period, influenza disease activity will have returned to levels normally seen for seasonal influenza. It is expected that the pandemic virus will behave as a seasonal influenza A virus. At this stage, it is important to maintain surveillance and update pandemic preparedness and response plans accordingly. An intensive phase of recovery and evaluation may be required.

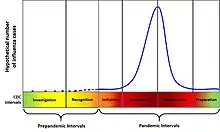

In 2014, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) introduced an analogous framework to the WHO's pandemic stages titled the Pandemic Intervals Framework.[131] It includes two pre-pandemic intervals,

- Investigation

- Recognition

and four pandemic intervals,

- Initiation

- Acceleration

- Deceleration

- Preparation

It also includes a table defining the intervals and mapping them to the WHO pandemic stages.

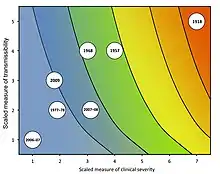

Severity

In 2014, the CDC adopted the Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework (PSAF) to assess the severity of pandemics.[131] The PSAF superseded the 2007 linear Pandemic Severity Index, which assumed 30% spread and measured case fatality rate (CFR) to assess the severity and evolution of the pandemic.[133]

Historically, measures of pandemic severity were based on the case fatality rate.[134] However, the case fatality rate might not be an adequate measure of pandemic severity during a pandemic response because:[132]

- Deaths may lag several weeks behind cases, making the case fatality rate an underestimate

- The total number of cases may not be known, making the case fatality rate an overestimate[135]

- A single case fatality rate for the entire population may obscure the effect on vulnerable sub-populations, such as children, the elderly, those with chronic conditions, and members of certain racial and ethnic minorities

- Fatalities alone may not account for the full effects of the pandemic, such as absenteeism or demand on healthcare services

To account for the limitations of measuring the case fatality rate alone, the PSAF rates severity of a disease outbreak on two dimensions: clinical severity of illness in infected persons; and the transmissibility of the infection in the population.[132] Each dimension can be measured using more than one measure, which are scaled to allow comparison of the different measures.

Management of a flu pandemic

Strategies to prevent a flu pandemic

This section contains strategies to prevent a flu pandemic by a Council on Foreign Relations panel.[136]

If influenza remains an animal problem with limited human-to-human transmission it is not a pandemic, though it continues to pose a risk. To prevent the situation from progressing to a pandemic, the following short-term strategies have been put forward:

- Culling and vaccinating livestock

- Vaccinating poultry workers against common flu

- Limiting travel in areas where the virus is found[136]

The rationale for vaccinating poultry workers against common flu is that it reduces the probability of common influenza virus recombining with avian H5N1 virus to form a pandemic strain. Longer-term strategies proposed for regions where highly pathogenic H5N1 is endemic in wild birds have included:

- changing local farming practices to increase farm hygiene and reduce contact between livestock and wild birds.

- altering farming practices in regions where animals live in close, often unsanitary quarters with people, and changing the practices of open-air "wet markets" where birds are kept for live sale and slaughtered on-site. A challenge to implementing these measures is widespread poverty, frequently in rural areas, coupled with a reliance upon raising fowl for purposes of subsistence farming or income without measures to prevent propagation of the disease.

- changing local shopping practices from purchase of live fowl to purchase of slaughtered, pre-packaged fowl.

- improving veterinary vaccine availability and cost.[136]

Strategies to slow down a flu pandemic

Public response measures

The main ways available to tackle a flu pandemic initially are behavioural. Doing so requires a good public health communication strategy and the ability to track public concerns, attitudes and behaviour. For example, the Flu TElephone Survey Template (FluTEST) was developed for the UK Department of Health as a set of questions for use in national surveys during a flu pandemic.[137]

- Social distancing: By traveling less, implementing remote work, or closing schools, there is less opportunity for the virus to spread. Reduce the time spent in crowded settings if possible. And keep your distance (preferably at least 1 metre) from people who show symptoms of influenza-like illness, such as coughing and sneezing.[138] However, social distancing during a pandemic flu will likely carry severe mental health consequences; therefore, sequestration protocols should take mental health issues into consideration.[139]

- Respiratory hygiene: Advise people to cover their coughs and sneezes. If using a tissue, make sure you dispose of it carefully and then clean your hands immediately afterwards. (See "Handwashing Hygiene" below.) If you do not have a tissue handy when you cough or sneeze, cover your mouth as much as possible with the crook of your elbow.[138]

- Handwashing hygiene: Frequent handwashing with soap and water (or with an alcohol-based hand sanitizer) is very important, especially after coughing or sneezing, and after contact with other people or with potentially contaminated surfaces (such as handrails, shared utensils, etc.)[140]

- Other hygiene: Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth as much as possible.[138]

- Masks: No mask can provide a perfect barrier, but products that meet or exceed the NIOSH N95 standard recommended by the World Health Organization are thought to provide good protection. WHO recommends that health-care workers wear N95 masks and that patients wear surgical masks (which may prevent respiratory secretions from becoming airborne).[141] Any mask may be useful to remind the wearer not to touch the face. This can reduce infection due to contact with contaminated surfaces, especially in crowded public places where coughing or sneezing people have no way of washing their hands. The mask itself can become contaminated and must be handled as medical waste when removed.

- Risk communication: To encourage the public to comply with strategies to reduce the spread of disease, "communications regarding possible community interventions [such as requiring sick people to stay home from work, closing schools] for pandemic influenza that flow from the federal government to communities and from community leaders to the public not overstate the level of confidence or certainty in the effectiveness of these measures."[142]

The Institute of Medicine has published a number of reports and summaries of workshops on public policy issues related to influenza pandemics. They are collected in Pandemic Influenza: A Guide to Recent Institute of Medicine Studies and Workshops,[143] and some strategies from these reports are included in the list above. Relevant learning from the 2009 flu pandemic in the UK was published in Health Technology Assessment, volume 14, issue 34.[144][145][146][147][148] Asymptomatic transmission appears to play a small role, but was not well studied by 2009.[149]

Anti-viral drugs

There are two groups of antiviral drugs available for the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza: neuraminidase inhibitors such as Oseltamivir (trade name Tamiflu) and Zanamivir (trade name Relenza), and adamantanes such as amantadine and rimantadine. Due to the high rate of side effects and risk of antiviral resistance, use of adamantanes to fight influenza is limited.[150]

Many nations, as well as the World Health Organization, are working to stockpile antiviral drugs in preparation for a possible pandemic. Oseltamivir is the most commonly sought drug, since it is available in pill form. Zanamivir is also considered for use, but it must be inhaled. Other anti-viral drugs are less likely to be effective against pandemic influenza.

Both Tamiflu and Relenza are in short supply, and production capabilities are limited in the medium term. Some doctors say that co-administration of Tamiflu with probenecid could double supplies.[151]

There also is the potential of viruses to evolve drug resistance. Some H5N1-infected persons treated with oseltamivir have developed resistant strains of that virus.

Vaccines

A vaccine probably would not be available in the initial stages of population infection.[152] A vaccine cannot be developed to protect against a virus which does not exist yet. The avian flu virus H5N1 has the potential to mutate into a pandemic strain, but so do other types of flu virus. Once a potential virus is identified and a vaccine is approved, it normally takes five to six months before the vaccine becomes available.[153]

The capability to produce vaccines varies widely from country to country; only 19 countries are listed as "influenza vaccine manufacturers" according to the World Health Organization.[154] It is estimated that, in a best scenario situation, 750 million doses could be produced each year, whereas it is likely that each individual would need two doses of the vaccine to become immuno-competent. Distribution to and inside countries would probably be problematic.[155] Several countries, however, have well-developed plans for producing large quantities of vaccine. For example, Canadian health authorities say that they are developing the capacity to produce 32 million doses within four months, enough vaccine to inoculate every person in the country.[156]

Another concern is whether countries which do not manufacture vaccines themselves, including those where a pandemic strain is likely to originate, will be able to purchase vaccine to protect their population. Cost considerations aside, they fear that the countries with vaccine-manufacturing capability will reserve production to protect their own populations and not release vaccines to other countries until their own population is protected. Indonesia has refused to share samples of H5N1 strains which have infected and killed its citizens until it receives assurances that it will have access to vaccines produced with those samples. So far, it has not received those assurances.[157] However, in September 2009, Australia, Brazil, France, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA agreed to make 10 percent of their H1N1 vaccine supply available to less-developed countries.[158]

There are two serious technical problems associated with the development of a vaccine against H5N1. The first problem is this: seasonal influenza vaccines require a single injection of 15 μg haemagluttinin in order to give protection; H5 seems to evoke only a weak immune response and a large multicentre trial found that two injections of 90 µg H5 given 28 days apart provided protection in only 54% of people.[159] Even if it is considered that 54% is an acceptable level of protection, the world is currently capable of producing only 900 million doses at a strength of 15 μg (assuming that all production were immediately converted to manufacturing H5 vaccine); if two injections of 90 μg are needed then this capacity drops to only 70 million.[160] Trials using adjuvants such as alum, AS03, AS04 or MF59 to try and lower the dose of vaccine are urgently needed. The second problem is this: there are two circulating clades of virus, clade 1 is the virus originally isolated in Vietnam, clade 2 is the virus isolated in Indonesia. Vaccine research has mostly been focused on clade 1 viruses, but the clade 2 virus is antigenically distinct and a clade 1 vaccine will probably not protect against a pandemic caused by clade 2 virus.

Since 2009, most vaccine development efforts have been focused on the current pandemic influenza virus H1N1. As of July 2009, more than 70 known clinical trials have been completed or are ongoing for pandemic influenza vaccines.[161] In September 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration approved four vaccines against the 2009 H1N1 influenza virus, and expected the initial vaccine lots to be available within the following month.[162]

Government preparations for a potential H5N1 pandemic (2003–2009)

According to The New York Times as of March 2006, "governments worldwide have spent billions planning for a potential influenza pandemic: buying medicines, running disaster drills, [and] developing strategies for tighter border controls" due to the H5N1 threat.[163]

[T]he United States is collaborating closely with eight international organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), and 88 foreign governments to address the situation through planning, greater monitoring, and full transparency in reporting and investigating avian influenza occurrences. The United States and these international partners have led global efforts to encourage countries to heighten surveillance for outbreaks in poultry and significant numbers of deaths in migratory birds and to rapidly introduce containment measures. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Departments of State, Health and Human Services (HHS), and Agriculture (USDA) are coordinating future international response measures on behalf of the White House with departments and agencies across the federal government.[164]

Together steps are being taken to "minimize the risk of further spread in animal populations", "reduce the risk of human infections", and "further support pandemic planning and preparedness".[164]

Ongoing detailed mutually coordinated onsite surveillance and analysis of human and animal H5N1 avian flu outbreaks are being conducted and reported by the USGS National Wildlife Health Center, the CDC, the ECDC, the World Health Organization, the European Commission, the National Influenza Centers, and others.[165]

United Nations

In September 2005, David Nabarro, a lead UN health official, warned that a bird flu outbreak could happen at any time and had the potential to kill 5–150 million people.[166]

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO), believing that the world was closer to another influenza pandemic than it has been any time since 1968, when the last of the 20th century's three pandemics swept the globe, has developed guidelines on pandemic influenza preparedness and response. The March 2005 plan includes guidance on roles and responsibilities in preparedness and response; information on pandemic phases; and recommended actions for before, during, and after a pandemic.[167]

United States

"[E]fforts by the federal government to prepare for pandemic influenza at the national level include a $100 million DHHS initiative in 2003 to build U.S. vaccine production. Several agencies within Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)—including the Office of the Secretary, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), CDC, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)—are in the process of working with vaccine manufacturers to facilitate production of pilot vaccine lots for both H5N1 and H9N2 strains as well as contracting for the manufacturing of 2 million doses of an H5N1 vaccine. This H5N1 vaccine production will provide a critical pilot test of the pandemic vaccine system; it will also be used for clinical trials to evaluate dose and immunogenicity and can provide initial vaccine for early use in the event of an emerging pandemic."[168]

Each state and territory of the United States has a specific pandemic flu plan which covers avian flu, swine flu (H1N1), and other potential influenza epidemics. The state plans together with a professionally vetted search engine of flu related research, policies, and plans, is available at the current portal: Pandemic Flu Search.

On 26 August 2004, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Tommy Thompson released a draft Pandemic Influenza Response and Preparedness Plan,[169] which outlined a coordinated national strategy to prepare for and respond to an influenza pandemic. Public comments were accepted for 60 days.

In a speech before the United Nations General Assembly on 14 September 2005, President George W. Bush announced the creation of the International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza. The Partnership brings together nations and international organizations to improve global readiness by:

- elevating the issue on national agendas;

- coordinating efforts among donor and affected nations;

- mobilizing and leveraging resources;

- increasing transparency in disease reporting and surveillance; and

- building capacity to identify, contain and respond to a pandemic influenza.

On 5 October 2005, Democratic Senators Harry Reid, Evan Bayh, Dick Durbin, Ted Kennedy, Barack Obama, and Tom Harkin introduced the Pandemic Preparedness and Response Act as a proposal to deal with a possible outbreak.[170]

On 27 October 2005, the Department of Health and Human Services awarded a $62.5 million contract to Chiron Corporation to manufacture an avian influenza vaccine designed to protect against the H5N1 influenza virus strain. This followed a previous awarded $100 million contract to Sanofi Pasteur, the vaccines business of Sanofi, for avian flu vaccine.

In October 2005, Bush urged bird flu vaccine manufacturers to increase their production.[171]

On 1 November 2005, Bush unveiled the National Strategy To Safeguard Against The Danger of Pandemic Influenza.[172] He also submitted a request to Congress for $7.1 billion to begin implementing the plan. The request includes $251 million to detect and contain outbreaks before they spread around the world; $2.8 billion to accelerate development of cell-culture technology; $800 million for development of new treatments and vaccines; $1.519 billion for the Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Defense to purchase influenza vaccines; $1.029 billion to stockpile antiviral medications; and $644 million to ensure that all levels of government are prepared to respond to a pandemic outbreak.[173]

On 6 March 2006, Mike Leavitt, Secretary of Health and Human Services, said U.S. health agencies are continuing to develop vaccine alternatives that will protect against the evolving avian influenza virus.[174]

The U.S. government, bracing for the possibility that migrating birds could carry a deadly strain of bird flu to North America, plans to test nearly eight times as many wild birds starting in April 2006 as have been tested in the past decade.[175]

On 8 March 2006, Dr. David Nabarro, senior UN coordinator for avian and human influenza, said that given the flight patterns of wild birds that have been spreading avian influenza (bird flu) from Asia to Europe and Africa, birds infected with the H5N1 virus could reach the Americas within the next six to 12 months.[176]

July 5, 2006, (CIDRAP News) – "In an update on pandemic influenza preparedness efforts, the federal government said last week it had stockpiled enough vaccine against H5N1 avian influenza virus to inoculate about 4 million people and enough antiviral medication to treat about 6.3 million."[177]

Canada

The Public Health Agency of Canada follows the WHO's categories, but has expanded them.[178] The avian flu scare of 2006 prompted The Canadian Public Health Agency to release an updated Pandemic Influenza Plan for Health Officials. This document was created to address the growing concern over the hazards faced by public health officials when exposed to sick or dying patients.

Malaysia

Since the Nipah virus outbreak in 1999, the Malaysian Health Ministry have put in place processes to be better prepared to protect the Malaysian population from the threat of infectious diseases. Malaysia was fully prepared during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) situation (Malaysia was not a SARS-affected country) and the episode of the H5N1 outbreak in 2004.

The Malaysian government has developed a National Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Plan (NIPPP) which serves as a time bound guide for preparedness and response plan for influenza pandemic. It provides a policy and strategic framework for a multisectoral response and contains specific advice and actions to be undertaken by the Ministry of Health at the different levels, other governmental departments and agencies and non-governmental organizations to ensure that resources are mobilized and used most efficiently before, during and after a pandemic episode.

See also

- Timeline of influenza

- List of epidemics

Citations

- Klenk HD, Matrosovich M, Stech J (2008). "Avian Influenza: Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Host Range". In Mettenleiter TC, Sobrino F (eds.). Animal Viruses: Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-22-6.

- Kawaoka Y, ed. (2006). Influenza Virology: Current Topics. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-06-6.

- "Current WHO phase of pandemic alert". World Health Organization, 2009

- World Health Organization. "World now at the start of 2009 influenza pandemic".

- "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 – update 74". Situation updates – Pandemic (H1N1) 2009. World Health Organization. 13 November 2009. Archived from the original on 15 November 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- St Mouritz AA (1921). 'The Flu' A Brief World History of Influenza. Honolulu: Advertiser Publishing Co., Ltd. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Merck Manual Home Edition. "Influenza". Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Eccles R (2005). "Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 5 (11): 718–25. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70270-X. PMC 7185637. PMID 16253889.

- Duda K. "Seasonal Flu vs. Stomach Flu". About, Inc., A part of The New York Times Company. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- Suarez DL, Spackman E, Senne DA, Bulaga L, Welsch AC, Froberg K (2003). "The effect of various disinfectants on detection of avian influenza virus by real time RT-PCR". Avian Dis. 47 (3 Suppl): 1091–95. doi:10.1637/0005-2086-47.s3.1091. PMID 14575118. S2CID 8612187.

- Avian Influenza (Bird Flu): Implications for Human Disease. Physical characteristics of influenza A viruses. UMN CIDRAP.

- "Flu viruses 'can live for decades' on ice". The New Zealand Herald. Reuters. 30 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Copeland CS (November–December 2013). "Deadliest Catch: Elusive, evolving flu difficult to predict" (PDF). Healthcare Journal of Baton Rouge: 32–36.

- "Avian influenza ("bird flu") fact sheet". World Health Organization. February 2006. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- "Influenza vaccines: WHO position paper" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 80 (33): 277–88. 19 August 2005.

- Villegas P (August 1998). "Viral diseases of the respiratory system". Poultry Science. 77 (8): 1143–45. doi:10.1093/ps/77.8.1143. PMC 7107121. PMID 9706079. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- Horwood F, Macfarlane J (2002). "Pneumococcal and influenza vaccination: current situation and future prospects". Thorax. 57 Suppl 2: II24–30. PMC 1766003. PMID 12364707.

- Palese P (December 2004). "Influenza: old and new threats". Nature Medicine. 10 (12 Suppl): S82–87. doi:10.1038/nm1141. PMID 15577936. S2CID 1668689.

- See the articles for references that use these names.

- Harder TC, Werner O (2006). "Avian Influenza". In Kamps BS, Hoffman C, Preiser W (eds.). Influenza Report 2006. Paris, France: Flying Publisher. ISBN 978-3-924774-51-6.

- "Pandemic Influenza Overview". CIDRAP – Center for Infectious Disease Research And Policy. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010.

- Zhu X, Yu W, McBride R, Li Y, Chen LM, Donis RO, et al. (January 2013). "Hemagglutinin homologue from H17N10 bat influenza virus exhibits divergent receptor-binding and pH-dependent fusion activities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (4): 1458–63. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1458Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218509110. PMC 3557073. PMID 23297216.

- Roos R, Schnirring L (1 February 2007). "HHS ties pandemic mitigation advice to severity". University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP). Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- Barry JM (2005). "1 The Story of Influenza: 1918 Revisited: Lessons and Suggestions for Further Inquiry". In Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon SM (eds.). The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). The National Academies Press. p. 62. doi:10.17226/11150. ISBN 978-0-309-09504-4. PMID 20669448.

- Barry JM (2005). "1 The Story of Influenza: 1918 Revisited: Lessons and Suggestions for Further Inquiry". In Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon SM (eds.). The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). The National Academies Press. p. 66. doi:10.17226/11150. ISBN 978-0-309-09504-4. PMID 20669448.

- Barry JM (2005). "1 The Story of Influenza: 1918 Revisited: Lessons and Suggestions for Further Inquiry". In Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon SM (eds.). The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). The National Academies Press. p. 59. doi:10.17226/11150. ISBN 978-0-309-09504-4. PMID 20669448.

- Barry JM (2005). "Chapter 1: The Story of Influenza: 1918 Revisited: Lessons and Suggestions for Further Inquiry". In Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon SM (eds.). The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). The National Academies Press. pp. 60–61. doi:10.17226/11150. ISBN 978-0-309-09504-4. PMID 20669448.

- Barry JM (2005). "1 The Story of Influenza: 1918 Revisited: Lessons and Suggestions for Further Inquiry". In Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon SM (eds.). The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). The National Academies Press. p. 63. doi:10.17226/11150. ISBN 978-0-309-09504-4. PMID 20669448.

- Barry JM (2005). "1 The Story of Influenza: 1918 Revisited: Lessons and Suggestions for Further Inquiry". In Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon SM (eds.). The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). The National Academies Press. p. 61. doi:10.17226/11150. ISBN 978-0-309-09504-4. PMID 20669448.

- Potter CW (October 2006). "A History of Influenza". J Appl Microbiol. 91 (4): 572–79. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290.

- Hilleman MR (August 2002). "Realities and enigmas of human viral influenza: pathogenesis, epidemiology and control". Vaccine. 20 (25–26): 3068–87. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00254-2. PMID 12163258.

- Potter CW (October 2001). "A history of influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290. S2CID 26392163.

- Biggerstaff M, Cauchemez S, Reed C, Gambhir M, Finelli L (September 2014). "Estimates of the reproduction number for seasonal, pandemic, and zoonotic influenza: a systematic review of the literature". BMC Infectious Diseases. 14 (1): 480. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-480. PMC 4169819. PMID 25186370.

- Valleron AJ, Cori A, Valtat S, Meurisse S, Carrat F, Boëlle PY (May 2010). "Transmissibility and geographic spread of the 1889 influenza pandemic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (19): 8778–81. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8778V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000886107. PMC 2889325. PMID 20421481.

- Mills CE, Robins JM, Lipsitch M (December 2004). "Transmissibility of 1918 pandemic influenza". Nature. 432 (7019): 904–6. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..904M. doi:10.1038/nature03063. PMC 7095078. PMID 15602562.

- Taubenberger JK, Morens DM (January 2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (1): 15–22. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050979. PMC 3291398. PMID 16494711.

- "Report of the Review Committee on the Functioning of the International Health Regulations (2005) in relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009" (PDF). 5 May 2011. p. 37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Spreeuwenberg P, Kroneman M, Paget J (December 2018). "Reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic". American Journal of Epidemiology. 187 (12): 2561–2567. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy191. PMID 30202996.

- Morens DM, Fauci AS (April 2007). "The 1918 influenza pandemic: insights for the 21st century". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 195 (7): 1018–28. doi:10.1086/511989. PMID 17330793.

- Johnson NP, Mueller J (2002). "Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 "Spanish" influenza pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 76 (1): 105–15. doi:10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. PMID 11875246. S2CID 22974230.

- Lin II R, Karlamangla S (6 March 2020). "Why the coronavirus outbreak isn't likely to be a repeat of the 1918 Spanish flu". Los Angeles Times.

- Schwarzmann SW, Adler JL, Sullivan RJ, Marine WM (June 1971). "Bacterial pneumonia during the Hong Kong influenza epidemic of 1968-1969". Archives of Internal Medicine. 127 (6): 1037–41. doi:10.1001/archinte.1971.00310180053006. PMID 5578560.

- Michaelis M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J (August 2009). "Novel swine-origin influenza A virus in humans: another pandemic knocking at the door". Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 198 (3): 175–83. doi:10.1007/s00430-009-0118-5. PMID 19543913. S2CID 20496301.

- Donaldson LJ, Rutter PD, Ellis BM, Greaves FE, Mytton OT, Pebody RG, Yardley IE (December 2009). "Mortality from pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza in England: public health surveillance study". BMJ. 339: b5213. doi:10.1136/bmj.b5213. PMC 2791802. PMID 20007665.

- "First Global Estimates of 2009 H1N1 Pandemic Mortality Released by CDC-Led Collaboration". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 25 June 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Kelly H, Peck HA, Laurie KL, Wu P, Nishiura H, Cowling BJ (5 August 2011). "The age-specific cumulative incidence of infection with pandemic influenza H1N1 2009 was similar in various countries prior to vaccination". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e21828. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621828K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021828. PMC 3151238. PMID 21850217.

- Dawood FS, Iuliano AD, Reed C, Meltzer MI, Shay DK, Cheng PY, et al. (September 2012). "Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: a modelling study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 12 (9): 687–95. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70121-4. PMID 22738893.

- Riley S, Kwok KO, Wu KM, Ning DY, Cowling BJ, Wu JT, et al. (June 2011). "Epidemiological characteristics of 2009 (H1N1) pandemic influenza based on paired sera from a longitudinal community cohort study". PLOS Medicine. 8 (6): e1000442. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000442. PMC 3119689. PMID 21713000.

- Wong JY, Kelly H, Ip DK, Wu JT, Leung GM, Cowling BJ (November 2013). "Case fatality risk of influenza A (H1N1pdm09): a systematic review". Epidemiology. 24 (6): 830–41. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182a67448. PMC 3809029. PMID 24045719.

- "WHO Europe – Influenza". World Health Organization (WHO). June 2009. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- "Key Facts About Influenza (Flu)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 October 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Tokars JI, Olsen SJ, Reed C (May 2018). "Seasonal Incidence of Symptomatic Influenza in the United States". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 66 (10): 1511–1518. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1060. PMC 5934309. PMID 29206909.

- "Influenza: Fact sheet". World Health Organization (WHO). 6 November 2018. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- "H1N1 fatality rates comparable to seasonal flu". The Malaysian Insider. Washington, D.C., USA. Reuters. 17 September 2009. Archived from the original on 20 October 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- Ryan, Jeffrey R., ed. (2008). "Chapter 1 - Past Pandemics and Their Outcome". Pandemic Influenza: Emergency Planning and Community Preparedness. CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-42006088-1.

The Asiatic Flu of 1889-1890 was first reported in Bukhara, Russia

- Shally-Jensen, Michael, ed. (2010). "Influenza". Encyclopedia of Contemporary American Social Issues. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 1510. ISBN 978-0-31339205-4.

The Asiatic flu killed roughly one million individuals

- Williams, Michelle Harris; Preas, Michael Anne (2015). "Influenza and Pneumonia Basics Facts and Fiction" (PDF). Maryland Department of Health - Developmental Disabilities Administration. University of Maryland. Pandemics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

Asiatic Flu 1889-1890 1 million

- Garmaroudi, Farshid S. (30 October 2007). "The Last Great Uncontrolled Plague of Mankind". Science Creative Quarterly. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

The Asiatic flu, 1889-1890: It was the last great pandemic of the nineteenth century.

- Rosenwald, Michael S. (7 April 2020). "History's deadliest pandemics, from ancient Rome to modern America". Washington Post. Covid mortality figure frequently updated.

- Taubenberger JK, Morens DM (2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (1): 15–22. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050979. PMC 3291398. PMID 16494711.

- Andrew Price-Smith, Contagion and Chaos (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009)

- Patterson KD, Pyle GF (1991). "The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 65 (1): 4–21. PMID 2021692.

- Spreeuwenberg P, Kroneman M, Paget J (December 2018). "Reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic". American Journal of Epidemiology. Oxford University Press. 187 (12): 2561–67. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy191. PMC 7314216. PMID 30202996.

- Potter CW (October 2001). "A history of influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290.

- "Historical Estimates of World Population". Census.gov. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Taubenberger JK, Reid AH, Janczewski TA, Fanning TG (December 2001). "Integrating historical, clinical and molecular genetic data in order to explain the origin and virulence of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 356 (1416): 1829–39. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.1020. PMC 1088558. PMID 11779381.

- Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Schonberger LB, Arden NH, Cox NJ, Fukuda K (July 1998). "Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution". J Infect Dis. 178 (1): 53–60. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.327.2581. doi:10.1086/515616. PMID 9652423.

- Greene, Jeffrey. Moline, Karen. [2006] (2006) The Bird Flu Pandemic. ISBN 0-312-36056-8.

- Goldsmith, Connie. (2007) Influenza: The Next Pandemic? 21st century publishing. ISBN 0-7613-9457-5

- Murray, Roderick (1969). "Production and testing in the USA of influenza virus vaccine made from the Hong Kong variant in 1968-69". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 495–496. hdl:10665/262478. PMC 2427701. PMID 5309463.

- Ziegler, T.; Mamahit, A.; Cox, N. J. (25 June 2018). "65 years of influenza surveillance by a World Health Organization-coordinated global network". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 12 (5): 558–565. doi:10.1111/irv.12570. PMC 6086847. PMID 29727518.

- "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1957, vol. 32, 19". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 19: 231–244. 10 May 1957. hdl:10665/211021 – via IRIS.

- Gomes Candau, Marcolino Gomes (April 1958). "The work of WHO, 1957: annual report of the Director-General to the World Health Assembly and to the United Nations". Official Records of the World Health Organization. hdl:10665/85693 – via IRIS.

- Kilbourne, Edwin D. (January 2006). "Influenza Pandemics of the 20th Century". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (1): 9–14. doi:10.3201/eid1201.051254. PMC 3291411. PMID 16494710.

- Taubenberger, Jeffery K.; Morens, David M. (April 2010). "Influenza: The Once and Future Pandemic". Public Health Reports. 125 (3_suppl): 18. doi:10.1177/00333549101250S305. PMC 2862331. PMID 20568566.

- Offit, Paul A. "Maurice R. Hilleman". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- "Symposium on the Asian Influenza Epidemic, 1957". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 51 (12): 1009–1018. 1 December 1958. doi:10.1177/003591575805101205. ISSN 0035-9157.

- Eickhoff, Theodore C. (July 1960). "The Epidemiology of Asian Influenza, 1957-1960". Stephen B. Thacker CDC Library – via CDC.

- Burch, George E.; Walsh, John J.; Mogabgab, William J. (May 1959). "Asian Influenza—Clinical Picture". A.M.A. Archives of Internal Medicine. 103 (5): 705.

- Louria, Donald B.; Blumenfeld, Herbert L.; Ellis, John T.; Kilbourne, Edwin D.; Rogers, David E. (January 1959). "Studies on Influenza in the Pandemic of 1957-1958. Ii. Pulmonary Complications of Influenza*†". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 38 (1 Pt 1-2): 262–263. doi:10.1172/JCI103791. PMC 444127. PMID 13620784.

- Dauer, Carl C. (September 1958). "Mortality in the 1957-58 Influenza Epidemic". Public Health Reports. 73 (9): 809. PMC 1951613. PMID 13579118.

- "Pandemic Influenza Risk Management: WHO Interim Guidance" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2013. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021.

- Burney, Leroy E. (October 1960). "Influenza Immunization". Public Health Reports. 75 (10): 944. doi:10.2307/4590965. JSTOR 4590965. PMC 1929542. PMID 19316369.

- Eickhoff, Theodore C.; Sherman, Ida L.; Serfling, Robert E. (3 June 1961). "Observations on Excess Mortality Associated with Epidemic Influenza". Journal of the American Medical Association. 176 (9): 776–782. doi:10.1001/jama.1961.03040220024005. PMID 13726091.

- Housworth, Jere; Langmuir, Alexander D. (July 1974). "EXCESS MORTALITY FROM EPIDEMIC INFLUENZA, 1957–1966". American Journal of Epidemiology. 100 (1): 43. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112007. PMID 4858301.

- Viboud, Cécile; Simonsen, Lone; Fuentes, Rodrigo; Flores, Jose; Miller, Mark A.; Chowell, Gerardo (1 March 2016). "Global Mortality Impact of the 1957–1959 Influenza Pandemic". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 213 (5): 738–745. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv534. PMC 4747626. PMID 26908781.

- Chowell, Gerardo; Simonsen, Lone; Fuentes, Rodrigo; Flores, Jose; Miller, Mark A.; Viboud, Cécile (May 2017). "Severe mortality impact of the 1957 influenza pandemic in Chile". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 11 (3): 230–239. doi:10.1111/irv.12439. PMC 5410718. PMID 27883281.

- Shope, Richard E. (February 1958). "Influenza: History, Epidemiology, and Speculation". Public Health Reports. 73 (2): 165–178. doi:10.2307/4590072. JSTOR 4590072. PMC 1951634. PMID 13506005.

- Trotter, Yates; Dunn, Frederick L.; Drachman, Robert H.; Henderson, Donald A.; Pizzi, Mario; Langmuir, Alexander D. (July 1959). "ASIAN INFLUENZA IN THE UNITED STATES, 1957–1958". American Journal of Epidemiology. 70 (1): 34–50. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120063. PMID 13670166.

- Murray, Roderick (1969). "Production and Testing in the USA of Influenza Virus Vaccine Made from the Hong Kong Variant in 1968-69". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 496. PMC 2427701. PMID 5309463.

- Paul WE (1993). Fundamental Immunology. New York: Plenum Press. p. 1273. ISBN 978-0-306-44407-4.

- "World health group issues alert Mexican president tries to isolate those with swine flu". Associated Press. 25 April 2009. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- "Asia on high alert for flu virus". BBC News. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1968-pandemic.html

- "Influenza Pandemic Plan. The Role of WHO and Guidelines for National and Regional Planning" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 1999. pp. 38, 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2020.

- Rozo M, Gronvall GK (August 2015). "The Reemergent 1977 H1N1 Strain and the Gain-of-Function Debate". mBio. 6 (4). doi:10.1128/mBio.01013-15. PMC 4542197. PMID 26286690.

- Michaelis M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J (August 2009). "Novel swine-origin influenza A virus in humans: another pandemic knocking at the door". Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 198 (3): 175–83. doi:10.1007/s00430-009-0118-5. PMID 19543913. S2CID 20496301.

- Rozo M, Gronvall GK (August 2015). "The Reemergent 1977 H1N1 Strain and the Gain-of-Function Debate". mBio. 6 (4). doi:10.1128/mBio.01013-15. PMC 4542197. PMID 26286690.

- Mermel LA (June 2009). "Swine-origin influenza virus in young age groups". Lancet. 373 (9681): 2108–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61145-4. PMID 19541030. S2CID 27656702.

- Wertheim JO (June 2010). "The re-emergence of H1N1 influenza virus in 1977: a cautionary tale for estimating divergence times using biologically unrealistic sampling dates". PLOS ONE. 5 (6): e11184. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511184W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011184. PMC 2887442. PMID 20567599.

- Furmanski M (September 2015). "The 1977 H1N1 Influenza Virus Reemergence Demonstrated Gain-of-Function Hazards". mBio. 6 (5): e01434-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01434-15. PMC 4611044. PMID 26419881.

- Zimmer SM, Burke DS (July 2009). "Historical perspective--Emergence of influenza A (H1N1) viruses". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (3): 279–85. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0904322. PMID 19564632.

- Nolan T (2 July 2009). "Was H1N1 leaked from a laboratory?". The BMJ. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Influenza A (H1N1) – update 11". WHO. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009.

- "WHO: Swine flu pandemic has begun, 1st in 41 years". Associated Press. 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- "Deadly new flu virus in U.S. and Mexico may go pandemic". New Scientist. 28 April 2009. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- Greenbaum JA, Kotturi MF, Kim Y, Oseroff C, Vaughan K, Salimi N, et al. (December 2009). "Pre-existing immunity against swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses in the general human population". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (48): 20365–70. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620365G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911580106. PMC 2777968. PMID 19918065.

- Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 – update 70, "As of 1 November 2009 [...] Laboratory-confirmed cases of the pandemic influenza H1N1 as officially reported to the WHO by States Parties to the International Health Regulations (2005)". Also see the WHO page Situation updates – Pandemic (H1N1) 2009, which has clickable links for all 70 updates, starting with the initial report of 24 April 2009.

- Enserink M (10 August 2010). "WHO Declares Official End to H1N1 'Swine Flu' Pandemic". Science Insider. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "First Global Estimates of 2009 H1N1 Pandemic Mortality Released by CDC-Led Collaboration". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 25 June 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Dawood FS, Iuliano AD, Reed C, et al. (September 2012). "Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: a modelling study". Lancet Infect Dis. 12 (9): 687–95. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70121-4. PMID 22738893.

- "Key Facts About Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) and Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus". CDC. Archived from the original on 16 March 2005.

- "Scientists Move Closer to Understanding Flu Virus Evolution". Bloomberg News. 28 August 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- Chen GW, Chang SC, Mok CK, Lo YL, Kung YN, Huang JH, et al. (September 2006). "Genomic signatures of human versus avian influenza A viruses". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (9): 1353–60. doi:10.3201/eid1209.060276. PMC 3294750. PMID 17073083.

- de Jong MD, Bach VC, Phan TQ, Vo MH, Tran TT, Nguyen BH, Beld M, Le TP, Truong HK, Nguyen VV, Tran TH, Do QH, Farrar J (17 February 2005). "Fatal avian influenza A (H5N1) in a child presenting with diarrhea followed by coma". N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (7): 686–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044307. PMID 15716562.

- "The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005)" The National Academies Press, p. 7

- Herring DA, Swedlund AC, eds. (2010). Plagues and Epidemics: Infected Spaces Past and Present. Wenner-Gren International Symposium Series (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 185. ISBN 978-1847885487.

- "Hazard in Hunt for New Flu: Looking for Bugs in All the Wrong Places". The New York Times, 8 November 2005.

- "WHO fears pandemic is 'imminent'". BBC News. 30 April 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "WHO declares swine flu pandemic". BBC News. 11 June 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 74". Archived from the original on 10 May 2020.

- Detailed chart of its evolution here at PDF called Ecology and Evolution of the Flu Archived 9 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine