Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework

The Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework (PSAF) is an evaluation framework which uses quadrants to evaluate both the transmissibility and clinical severity of a pandemic and to combine these into an overall impact estimate.[1] Clinical severity is calculated via multiple measures including case fatality rate, case-hospitalization ratios, and deaths-hospitalizations ratios, while viral transmissibility is measured via available data among secondary household attack rates, school attack rates, workplace attack rates, community attack rates, rates of emergency department and outpatient visits for influenza-like illness.[2][3]

The PSAF superseded the 2007 linear Pandemic Severity Index (PSI), which assumed 30% spread and measured case fatality rate (CFR) to assess the severity and evolution of the pandemic.[3][4] The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) adopted the PSAF as its official pandemic severity assessment tool in 2014,[4] and it was the official pandemic severity assessment tool listed in the CDC's National Pandemic Strategy at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.[5]

Measures used in the framework

Historically, measures of pandemic severity were based on the case fatality rate.[6] However, the case fatality rate might not be an adequate measure of pandemic severity during a pandemic response because:[2]

- Deaths may lag several weeks behind cases, making the case fatality rate an underestimate

- The total number of cases may not be known, making the case fatality rate an overestimate[7]

- A single case fatality rate for the entire population may obscure the effect on vulnerable sub-populations, such as children, the elderly, those with chronic conditions, and members of certain racial and ethnic minorities

- Fatalities alone may not account for the full effects of the pandemic, such as absenteeism or demand on healthcare services

To account for the limitations of measuring the case fatality rate alone, the PSAF rates severity of a disease outbreak on two dimensions: clinical severity of illness in infected persons; and the transmissibility of the infection in the population.[2] Each dimension can be measured using more than one measure, which are scaled to facilitate comparison. Having multiple measures for each dimension offers flexibility to choose a measure that is readily available, accurate, and representative of the impact of the pandemic. It also allows comparison across measures for a more complete understanding of the severity. The framework gives commentary on the strengths and limitations of various measures of clinical severity and transmissibility as well as guidelines for scaling them. It also provides examples of assessing past pandemics using the framework.[2]

Measures of transmissibility

The original documentation for the PSAF includes the following as potential measures of transmissibility:[2]

- Basic reproduction number R0 and serial interval

- Estimated attack rate (community, household, school, workplace)

- Medically-attended outpatient influenza-like illness visits

- Underlying population immunity

- Genetic markers of transmissibility

- Animal transmission experiments

- School/workplace absenteeism, including healthcare workers

Measures of clinical severity

The original documentation for the PSAF includes the following as potential measures of clinical severity:[2]

- Case fatality rate and case hospitalization rate

- Ratio of deaths to hospitalizations

- Genetic markers of virulence

- Animal immunopathologic experiments

- Percent of emergency department visits that resulted in hospitalization

- Percent of hospitalizations admitted to intensive care unit

- Rate of hospitalization

- Excess deaths

Severity of past pandemics using the Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework

The original developers of the PSAF provided a model for the number of hypothetical deaths in the United States 2010 population of an influenza pandemic using the PSAF. While the axes of the PSAF are scaled measures of transmissibility and clinical severity, this model uses the case-fatality ratio instead of the scaled measure of clinical severity and the cumulative incidence of infection instead of the scaled measure of transmissibility.[2]

Influenza severity

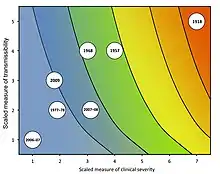

During its development, the PSAF was applied to past influenza pandemics and epidemics, resulting in the following assessments:[2]

| Influenza pandemic or flu season | Transmissibility | Clinical Severity |

|---|---|---|

| Spanish flu pandemic | 5 | 7 |

| 1957–1958 influenza pandemic | 4 | 4 |

| 1968 influenza pandemic | 4 | 3 |

| 1977-1978 influenza epidemic | 2 | 2 |

| 2006-2007 flu season | 1 | 1 |

| 2007-2008 flu season | 2 | 3 |

| 2009 swine flu pandemic | 3 | 2 |

COVID-19 pandemic severity

A team of Brazilian researchers preliminarily assessed the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic using the PSAF in April 2020 based on Chinese data through 11 February 2020. In their preliminary assessment, they rate COVID-19's scaled transmissibility at 5 and its scaled clinical severity at 4 to 7, placing the COVID-19 pandemic in the "very high severity" quadrant. This preliminary assessment ranks the COVID-19 pandemic as the most severe pandemic since the 1918 influenza pandemic.[8]

| Human and pandemic coronaviruses | Transmissibility | Clinical Severity |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 pandemic | 5 | 4~7 |

While the CDC has not published a PSAF rating for the COVID-19 pandemic, they maintain best estimates of some of the relevant transmissibility and clinical severity measures for scenario planning.[9]

SARS-CoV-2 variants

Different variants of SARS-CoV-2 can have unique transmissibility and clinical severity. Multiple variants have been determined to have higher transmissibility and severity than the original strain.[10]

See also

References

- Roos, Robert (24 April 2017). "New CDC guidelines on flu pandemic measures reflect 2009 lessons". Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Reed, Carrie; Biggerstaff, Matthew; Finelli, Lyn; Koonin, Lisa M.; Beauvais, Denise; Uzicanin, Amra; Plummer, Andrew; Bresee, Joe; Redd, Stephen C.; Jernigan, Daniel B. (January 2013). "Novel framework for assessing epidemiologic effects of influenza epidemics and pandemics". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 19 (1): 85–91. doi:10.3201/eid1901.120124. ISSN 1080-6059. PMC 3557974. PMID 23260039.

- Qualls, Noreen; Levitt, Alexandra; Kanade, Neha; Wright-Jegede, Narue; Dopson, Stephanie; Biggerstaff, Matthew; Reed, Carrie; Uzicanin, Amra (21 April 2017). "Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza — United States, 2017" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 66 (RR-1): 1–34. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6601a1. ISSN 1057-5987. PMC 5837128. PMID 28426646. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Holloway, Rachel; Rasmussen, Sonja A.; Zaza, Stephanie; Cox, Nancy J.; Jernigan, Daniel B. (26 September 2014). "Updated Preparedness and Response Framework for Influenza Pandemics" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 63 (RR-6): 1–18. ISSN 1057-5987. PMID 25254666. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

This report provides an update to the 2008 framework to reflect experiences with 2009 H1N1 and recent responses to localized outbreaks of novel influenza A viruses. The revised framework also incorporates the recently developed Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT) (12) and Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework (PSAF) (13)...PSAF replaces the Pandemic Severity Index as a severity assessment tool (13).

- "Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework (PSAF)". National Pandemic Strategy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 3 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Interim Pre-Pandemic Planning Guidance: Community Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Mitigation in the United States (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 2007. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-19. Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- Rajgor, Dimple D.; Lee, Meng Har; Archuleta, Sophia; Bagdasarian, Natasha; Quek, Swee Chye (27 March 2020). "The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Ltd. 20 (7): 776–777. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30244-9. PMC 7270047. PMID 32224313.

- Ribas Freitas, André Ricardo; Napimoga, Marcelo; Donalisio, Maria Rita (April 2020). "Assessing the severity of COVID-19". Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde. 29 (2): 5. doi:10.5123/S1679-49742020000200008. PMID 32267300. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "COVID-19 Pandemic Planning Scenarios". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021-03-19. Table 1. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- Tao, Kaiming; Tzou, Philip L.; Nouhin, Janin; Gupta, Ravindra K.; de Oliveira, Tulio; Kosakovsky Pond, Sergei L.; Fera, Daniela; Shafer, Robert W. (17 September 2021). "The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants". Nature Reviews Genetics. 22 (12): 757–773. doi:10.1038/s41576-021-00408-x. PMC 8447121. PMID 34535792.

The Alpha and Delta variants are each associated with increased transmissibility and greater disease severity because of immune evasion, and potentially because of higher virus levels resulting from the antagonism of innate immunity.