COVID-19 pandemic in Venezuela

The COVID-19 pandemic in Venezuela is part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The first two cases in Venezuela were confirmed on 13 March 2020;[2][3] the first death was reported on 26 March.[4] However, the first record of a patient claiming to have symptoms of coronavirus disease dates back to 29 February 2020,[5] with government officials suspecting that the first person carrying the virus could have entered the country as early as 25 February.[6]

| COVID-19 pandemic in Venezuela | |

|---|---|

Line for gas during the pandemic in Miranda | |

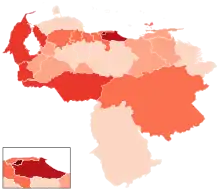

Federal entities with confirmed (red) cases (as of 1 November 2020)

No confirmed cases

1-1000 confirmed

1001-2500 confirmed

2501-5000 confirmed

5001-10000 confirmed

10001-20000 confirmed

≥20001 confirmed | |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | Venezuela |

| First outbreak | Wuhan, Hubei, China (global) Brazil, Colombia, Italy, Spain and the United States (imported) |

| Index case | Miranda State |

| Arrival date | 13 March 2020 (2 years, 7 months, 2 weeks and 5 days) |

| Confirmed cases | 376,311[1] (as of 5 October 2021) |

| Active cases | 4137[1] (as of 5 October 2021) |

| Recovered | 357,339[1] (as of 5 October 2021) |

Deaths | 4,539[1] (as of 5 October 2021) |

Territories | Capital District, all 23 states and 1 federal dependency |

| Government website | |

| covid19 coronavirusvenezuela | |

| Crisis in Venezuela |

|---|

|

|

|

Venezuela is particularly vulnerable to the wider effects of the pandemic because of its ongoing socioeconomic and political crisis causing massive shortages of food staples and basic necessities, including medical supplies. The mass emigration of Venezuelan doctors has also caused chronic staff shortages in hospitals.[7]

To prevent the spread of the disease into Venezuela, the governments of Brazil and Colombia temporarily closed their borders with Venezuela.[8][9][10] The Colombian government had placed 1 October as a tentative date for reopening the border.[11]

In February 2021, Venezuela started vaccinations with the Russian Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine produced by the Chinese company Sinopharm. It aimed to vaccinate 70 percent of the population by the end of 2021. An academic survey found that by the 1 September 2021, 10% of the Venezuelan population was fully vaccinated.[12] By the end of 2021, Venezuela had administered 30,049,714 doses of vaccine, about 52.7% of the country's population.[13][14]

Background

In January, Venezuela's Ministry of Popular Power for Health announced that the Rafael Rangel National Institute of Hygiene (Spanish: Instituto Nacional de Higiene Rafael Rangel) in Caracas would act as the observatory for non-influenza respiratory viruses, including coronaviruses in humans. It is the only health institution in the country with the ability to diagnose respiratory viruses and to operate logistically across the 23 states, the Capital District and the Federal Dependencies of Venezuela.[15]

In February, the Venezuelan government announced that the country had imposed epidemiological surveillance, restrictions and a plan to detect individuals with COVID-19 at the Simón Bolívar International Airport in Maiquetía, Venezuela's main international airport. They said Venezuela would receive diagnostic kits for the virus strain from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).[16]

Timeline

_-_Infizierte_(800px).svg.png.webp)

_-_Tote_(800px).svg.png.webp)

March

Venezuela reported its first official cases of coronavirus disease on 13 March 2020.[3] However, several days earlier a suspected case became controversial due to the state treatment of a whistleblower.[17] On 7 March, Fe y Alegría reported that a suspicious medical case was registered in Zulia: a 31-year-old who was not from Venezuela was examined at the Pedro Iturbe Hospital and later transferred to the University Hospital of Maracaibo. The patient had apparent symptoms and was discharged days later.[18] The state governor, Omar Prieto, asked the Public Ministry to investigate a University of Zulia professor, Freddy Pachano, for bringing attention to the suspected case in the state, and the NGO Espacio Público condemned Prieto for ordering such an investigation.[17] Nicolás Maduro declared a ban on protests on 12 March before cases were confirmed in Venezuela to prevent the spread of the outbreak, as well as a ban on flights from Europe and Colombia.[19]

The first cases, two on 13 March, were registered in the state of Miranda.[2][3] Colombian president Iván Duque closed the border with Venezuela effective from the next day.[8][9] On 14 March, the official number of cases rose by eight (to ten), and had spread across four states (Miranda, Apure, Aragua and Cojedes).[20] Communication Minister Jorge Rodríguez announced that flights from Panama and the Dominican Republic to the country would be suspended for 30 days, beginning on 15 March.[21]

Stay-at-home orders were announced on 15 March, when the country registered another seven cases, and introduced the next day across six states and the Caracas area.[22] The orders were dubbed "collective quarantine"; there are exceptions for transportation, health, and delivery of food.[22] It was on the first day of the quarantine across six states, 16 March, that Argentina's ambassador in Venezuela, Eduardo Porretti, tested positive for the virus,[23] and Nicolás Maduro announced that sixteen new cases were confirmed, bringing the total to 33. Based on this, Maduro extended the quarantine to the entire country.[24]

When Venezuela went into lockdown on 17 March, authorities in Brazil partially closed their border with Venezuela. Brazilian Health Minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta had urged closure of the border due to Venezuela's collapsing health system.[10] Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez announced three more cases the same day.[25] In the afternoon, a patient that would later test positive for coronavirus fled from a hospital in Propatria, in west Caracas.[26][27]

On 18 March, Delcy Rodríguez reported that the numbers of cases had not changed since the previous day.[28] By 21 March, the government reported 70 confirmed cases in the country.[29]

Economic measures to deal with the consequences of the pandemic were announced on 22 March, along with seven more cases.[30] Rent and credit payments were suspended for six months, accompanied by compensation in local currency for property owners and medium-sized businesses.[30] The measures also extended a 2015 policy that prevents companies from firing employees through December 2020.[30] The government said that no household would have their utilities cut off. The government also took over payment of wages for workers in non-essential companies that were not operating during the national emergency and gave workers in the informal sector a one-off social security payment.[31]

The first confirmed death from the disease was announced on 26 March.[4] Another death was reported the next day.[32][33] Also on 27 March, Delcy Rodríguez met with Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago Keith Rowley, with the meeting focused on the strategy being deployed in both countries to combat the pandemic.[34] There was also controversy on this day when NGO PROVEA revealed that around ninety people coming from Cúcuta, Colombia, were forcefully isolated on 25 March by the National Guard in Barqusimeto, Lara, without food or proper sanitary conditions.[35][36][37]

April

Information Minister Jorge Rodríguez first reported that there were more recoveries than new infections in Venezuela on 11 April.[38][39] Delcy Rodríguez and Nicolás Maduro announced an extension of the national quarantine and state of alarm for 30 days.[40]

After a sudden rise of the number of cases in Margarita Island, Nicolás Maduro announced a curfew the entire state of Nueva Esparta on 19 April.[41] 41 of the cases at the time, were related to Roberto Vahlis Baseball Academy. Some of its member had just arrived from Dominican Republic by plane.[42]

A 29-year-old man was killed by two gunshots to the head during riots in Upata, Bolívar state, caused by food and fuel shortages that were exacerbated by the lockdown since mid-March.[43] The message "Murió por hambre" (He died of hunger) was written in chalk besides the pool of blood that he left. Colectivos participated in the police operation to repress the riots, who used their motorcycles despite the fuel shortages. At least two people were injured and thirty others were arrested.[44]

May

Delcy Rodríguez reported the first cases of COVID-19 in Amazonas and Carabobo on 10 May. That left Delta Amacuro as the only unaffected state at that moment.[45]

Nicolás Maduro, on 12 May, extended the lockdown for 30 more days.[46] The restrictions to national flights were also extended 30 days by the national aeronautics institute INAC (Spanish: Instituto Nacional de Aeronáutica Civi).[47]

The first patient with COVID-19 in Delta Amacuro was reported on 13 May. As of that date, all states of Venezuela have reported at least a case of COVID-19.[48]

Mid May, Maracaibo reports a major outbreak of cases related to Las Pulgas, a popular market. The market was closed.[49]

After 34 days without a death report, a new deceased by COVID-19 was reported on 26 May.[50]

June

The easing of the lockdown started on 1 June, with gyms and shopping centers opening. Schools, courts and bars remain closed.[51]

As of 9 June the Venezuelan government had reduced re-emigrations to 400 per day, three days a week, a reduction of 80% from previous levels.[52]

The state of alarm was extended a third time for an additional month on 12 June.[53]

Opposition and health care workers in Maracaibo announced on the fourth week of June that hospitals in the city were filled and dozens of doctors and nursed were infected.[49] William Barrientos, a surgeon and opposition legislator, said that 40 health workers were infected with the virus. A nurse died in the Maracaibo Military Hospital. The authorities enabled 20 small and midsized hotels in Maracaibo to treat patients. Measures were increased in Zulia, Caracas and eight other states.[49]

July

Diosdado Cabello, vice-president of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela and president of the pro-government Constituent National Assembly announced he tested positive for COVID-19 on 9 July.[54]

Tareck El Aissami, the Minister of Petroleum and Omar Prieto, the Governor of Zulia also tested positive on 10 July.[55]

A member of the National Constituent Assembly and the Governor of the Capital District, Darío Vivas tested positive for COVID-19 on 19 July.[56]

August

Venezuela Minister of Communication and Information Jorge Rodríguez tested positive for COVID-19 on 13 August.[57] On the same day, Darío Vivas died of COVID-19 at the age of 70.[56]

February

In February 2021, Venezuela started vaccinating health care workers with the Russian Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine and started using a vaccine produced by the Chinese company Sinopharm. It aimed to vaccinate 70 percent of the population by the end of 2021.[58][59]

March

In March 2021, Juan Guaidó and the opposition National Assembly approved 30 million dollars to import Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccines. Delcy Rodríguez announced that permits for its use would not be conceded.[60] Venezuela decided not to approve use of the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine when several European countries suspended their vaccination programmes due to concerns over possible side-effects.[59]

October

School children and university students started going back to their classes in October 2021. The government claimed that 56% of the population had been vaccinated but Johns Hopkins University reported that less than 22% of the population had been fully vaccinated. Venezuelans could get vaccinated from the age of 11.[61]

Measures

Executive response

On 12 March, Nicolás Maduro declared a public health emergency in the country and suspended all inbound flights from Europe and Colombia for 30 days. He also announced that public gatherings were to be suspended and that the government would be evaluating whether or not to suspend flights from other regions in the coming weeks. According to Maduro, there had been 30 suspected cases in Venezuela, but these had all tested negative.[62]

After the first cases in the country were confirmed, Vice-President Delcy Rodríguez instructed all passengers of the 5 March and 8 March flights of Iberia 6673 to immediately enter into a mandatory preventive quarantine because two passengers tested positive.[63]

Rodríguez announced that all classes would be suspended at public and private schools from Monday 16 March until further notice,[64] while Néstor Reverol announced that the government would provide border control authorities with face masks, gloves and thermometers, without mentioning supplies for citizens and hospitals.[3] Reverol also announced that the operational control of all the police forces would be transferred to the Armed Forces in order to coordinate the action and contingency plan.[65]

On 14 March, authorities arrested two people for spreading false information about the virus, recording a video about fake cases in Los Teques.[66] SUDEBAN, the government's department related to banks and financial institutions, announced the suspension of banking activities, effective from 16 March.[67]

Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino López announced that, effective from 16 March, the Armed Forces would control access to the six states and the Capital District declared by Nicolás Maduro to be in quarantine.[68]

On 16 March, Maduro reversed the country's official position against the International Monetary Fund (IMF), asking the institution for US$5 billion to combat the pandemic,[69] a first during Maduro's presidency; he has been a critic of the institution.[70][71] The IMF also has had conflicts with the Venezuelan government in the past, as Maduro's predecessor Hugo Chávez had pledged to cut ties with the fund in 2007, and the IMF suspended US$400 million in special drawing rights during the Venezuelan presidential crisis in 2019.[72] The IMF rejected the deal as it was not clear, among its member states, on who it recognizes as Venezuela's president, Nicolás Maduro or Juan Guaidó.[73] According to a report by Bloomberg, the Maduro administration also tried to request aid of $1 billion from the IMF after the first request was denied.[74]

On 19 March, Rodríguez announced that 4,000 diagnosis kits were delivered from China to test for coronavirus disease. The government said that the Chinese diagnosis kits would benefit 300,000 Venezuelans and thanked the Chinese government and President Xi Jinping for their generosity. In a separate measure, Venezuela's INEA maritime authority has prohibited crews aboard ships docking in the country's ports from disembarking.[75] The same day, Maduro announced that he had received a letter from the United Nations (UN) Resident Coordinator and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Resident Representative Peter Grohmann, confirming that the organization "is ready to support the Venezuelan government in its fight against COVID-19." Maduro stressed that the UN has taken concrete actions, particularly in the areas of health and water, sanitation and hygiene, and "will support the Ministry of Health in the care and containment of the coronavirus." Likewise, they will offer support in the disclosure of reliable and updated information. China provided a further one million rapid antigen test kits in March 2020.[31]

On 20 March, Maduro said that Russia was considering "a significant donation of special humanitarian aid" to the country, such as medical equipment and kits for the diagnosis of COVID-19, which were expected to arrive by the following week.[76] On 23 March, Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza and Russian ambassador Sergei Melik-Bagdasarov announced that 10,000 diagnosis kits had been delivered from Russia, with more to be supplied in future shipments.[77] In a tweet, Maduro thanked the Russian government and President Vladimir Putin for their generosity and for standing in solidarity with the Venezuelan people.[78]

Maduro announced several economic measures on 23 March to deal with unemployment, the assumption of wage payment by the state, the suspension of rent and credit interests payments, the assignment of new bonds, the flexibility of new loans and credit, the prohibition of the cutting of telecommunication services and the guarantee of CLAP (Local Committees for Supply and Production) supplies.[79]

Russian Sputnik V vaccine

In September 2020, Maduro suggested administering the Russian Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine to the candidates in the upcoming legislative elections so that they could campaign safely. In October 2020, the Venezuelan government received a shipment of the Sputnik V vaccine. Venezuela was the first country in Latin America to participate in the Sputnik V trial, which involved around 2000 Venezuelan participants.[80] In December 2020, the Venezuelan government signed a contract to acquire enough doses of the Sputnik V vaccine for 10 million people.[81]

Doctors without Borders

The international aid group Doctors without Borders (MSF) stopped operations in Caracas in November 2020 due to government restrictions. About 150 doctors, that worked in Petare, a poor neighborhood, risk to lose their jobs.[82] Maribelsi Mancera, head nurse for MSF, stated that they do not understand the government decision.[82] Miguel Pizarro, Venezuela's representative in the United Nations, regretted the decision and criticized the government behavior against non governmental organizations trying to help with the crisis.[82]

National Assembly response

In March 2020, Juan Guaidó said that the country is experiencing one of the most serious health crises in its history, caused by the inaction of the Maduro government, and announced a series of measures in order to take "responsible measures against the pandemic."[83][84] These include the postponement of opposition protests and the creation of the Special Health Commission.[9][83] Guaidó also called for the entry of humanitarian aid from the United Nations, and said that health services are not impacted by international sanctions.[84]

The Committee of Electoral Candidacies, in charge of appointing a new National Electoral Council (CNE), announced that it would suspend its meetings because of the pandemic.[85]

Julio Castro, head of the Special Health Commission appointed by Juan Guaidó, said on 16 March that face masks are a prevention measure useful only for one day, and that once used the mask loses its effectiveness and can become a source of infection; he also said that Venezuelans have to take additional measures to deal with the pandemic.[86]

In March 2020, National Assembly deputy Jesús Yánez announced that the government of Taiwan donated 1,000 surgical masks as a measure to prevent the coronavirus pandemic. The masks were distributed in five stations of the Caracas Metro (Plaza Sucre, Pérez Bonalde, Plaza Venezuela, Chacao and Petare). Yánez highlighted that the metro is a means of transportation used by a large part of the population and is a breeding ground for the pandemic due to the crowding of people in closed spaces, should any one of them be carrying the virus.[87]

In March 2020, Guaidó's Special Health Commission collected 3,500 protection kits for caregivers at five hospitals on 16 March.[88]

On 21 March, Guaidó announced that he delivered medical kits to protect the health sector from the coronavirus pandemic. On his official Twitter account, he shared a video expressing that "We are protecting a sector that today is giving everything: the health sector, our doctors and nurses. To support them is to support us all. We must bring this help to hundreds who need it", and concluded "We can contain this emergency. Venezuela is in our hands."[89][90] Guaidó also announced the creation of the Human Rights Observatory as a response to the increase of human rights violations in the country during the social isolation orders.[91]

Guaidó called for the creation of a "national emergency government", not lead by Maduro, on 28 March. According to Guaidó, a loan of US$1.2 billion was ready to be given in support of a power-sharing coalition between pro-Maduro officials, the military and the opposition in order to fight the pandemic in Venezuela. If accepted, the money would go to assist families affected by the disease and its economic consequences.[92]

Juan Guaidó announced a financial help to health workers during the pandemic supported by Venezuelan funds frozen in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In August 2020, opposition parties announced that the request had been granted by the United States Department of the Treasury. In the statement, an amount of 300 USD would be granted to 62,000 health workers, with US$100 a month starting 23 August 2020 for those registered. The resources were planned to be distributed through AirTM, a digital payment platform, but after the announcement the access to the platform was blocked in Venezuela. A manual to circumvent the internet block using a virtual private network (VPN) was published afterwards. An amount of US$4.5 million to support Venezuelans at risk of death, was also announced.[93]

The "Health heroes" program of Guaidó is the first time that frozen funds in United States, as part of sanctions on Venezuela, were directly transferred to Venezuelan health workers. By November 2020, the second wave of payments were granted.[94]

Joint response

In June 2020, Carlos Alvarado, Maduro's health minister and Julio Castro, representing Juan Guaidó and the National Assembly, signed an unprecedent joint agreement with the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization. The accord seeks cooperation between Maduro's government and the opposition deputies of the National Assembly to handle the pandemic and seek funds.[95]

According to opposition lawmakers, Maduro administration violated the agreement in January 2021, as resources and equipment to handle the pandemic were transferred to facilities controlled by Maduro administration.[96]

Other responses

Baltazar Porras, Apostolic Administrator of Caracas, announced the suspension of ecclesiastic activities on 15 March, while assuring that temples would remain open, asking Venezuelans to avoid crowded places and to remain calm.[97]

The Health Ministry certified the microbiology laboratory of the University of the Andes, in Mérida state, to start carrying out tests to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 disease, on 18 March. Once the necessary supplies are received, the laboratory will be able to perform up to 20 tests per day and would be the second laboratory in the country to perform detection tests after the National Hygiene Institute in Caracas; it would be expected to carry out tests for the states of Mérida, Táchira, Trujillo and Barinas, and possibly other states in the west, as it is closer than the Hygiene Institute in Caracas.[98]

Three men that were playing dominoes outdoors during the quarantine were murdered on 21 March in the 23 de Enero parish, in Caracas, and two more were injured.[99] According to neighbors and relatives, a dozen members of the colectivo Tres Raíces arrived while they were playing and were responsible for their deaths; the witnesses accused the colectivo members of being linked with Iris Varela, Minister of Popular Power for the Prison Service, being linked to a CICPC officer, and of wearing FAES and National Police uniforms, announcing that they would protest as a response to the killings, in defiance of the quarantine.[100] The colectivo denied the accusations of being related to the government or police, saying that the murders were instead motivated by revenge.[99]

On late March 2020, the colectivos Tres Raíces and La Piedrita started imposing a paramilitary-enforced curfew in the 23 de Enero parish, increasing repression and imposing closure times to businesses.[99]

Reactions

Government reactions

Maduro asked people to not politicize the pandemic,[101] while also expressing concern as to how the country could control the pandemic with the United States-imposed sanctions.[2] Maduro called on US President Donald Trump to lift the sanctions so the country could acquire necessary medical supplies.[102]

Juan Guaidó said that since the start of the pandemic, human rights violations by Maduro's administration had increased, citing the murders in the 23 de Enero parish, the arrest of Darvinson Rojas, and human rights abuses against political prisoners, who are held in prisons with a high infection risk. Guaidó announced the creation of a Human Rights Observatory as a response.[91]

Other reactions

The Venezuelan Medical Federation expressed condemnation at how a medic in Zulia was forced to leave for Colombia after denouncing the inability of Venezuela to cope if the disease arrived;[103] it also asked for the release of the political prisoners in the country, who are vulnerable to the virus, specifically Roberto Marrero, Juan Requesens, and other lawmakers.[104]

In the Anzoátegui state, nurses denounced the lack of face masks, gloves and disposable gowns.[105]

Transparencia Venezuela asked for transparency and access to public information regarding the handling of the emergency.[106]

Media outlets, such as El Nacional, denounced the price increase of face masks.[107][108][109] Outlets have also reported on the violation of the quarantine for reasons such as buying food, medicines, and both cleaning and hygiene products, as well as the public services crisis, including the lack of drinking water, electric power, cooking gas, telephone signal and waste collection.[110]

International sanctions

The Virtual United States Embassy in Venezuela rejected claims from Nicolás Maduro and Jorge Arreaza that sanctions are preventing the government from purchasing medical supplies, saying that "medicines, medical supplies, spare parts and components for medical devices in Venezuela, or to people from third countries who buy specifically for resale from Venezuela are excluded from the sanctions."[111][112] Days later, Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza called the statements "the height of impudence and falsehood." He declared that Venezuelan government assets worth more than US$5 billion were blocked overseas, in addition to "Venezuela's ban on access to the international banking system."[113]

Former Attorney General Luisa Ortega Díaz declared that Maduro "lied" when saying that there were no medicines in the country because of the sanctions, saying that the reasons were incompetence and corruption.[114] The US Acting Assistant Secretary for Western Hemisphere Affairs Michael Kozak also accused Maduro of lying, saying that U.S. sanctions never block food or medicine purchases. He emphasized that shortages in Venezuela resulted from "the regime's theft of the nation's wealth."[115][116]

On 24 March, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet called for any sanctions imposed on Venezuela and other countries facing the pandemic such as Cuba, Iran, and Zimbabwe to be "urgently reevaluated" in order to avoid pushing strained medical systems into collapse. In a statement, Bachelet said: "At this crucial time, both for global public health reasons, and to support the rights and lives of millions of people in these countries, sectoral sanctions should be eased or suspended."[117][118] Bachelet also accentuated the need to protect health workers in these countries as authorities should not punish professionals that point out the deficiencies in the state response to the crisis.[117]

On 10 June 2021, Venezuelan officials announced they have been unable to complete payments for available vaccines from the COVAX program. Initially the transaction of $120 million was to be paid per agreement with Juan Guaidó using funds frozen in the United States via Washington's sanctions against Maduro, but later Venezuelan officials said they would use their own funds. Subsequently, Swiss bank UBS confirmed that four operations, totaling $4.6 million, "were blocked and under investigation." Vice President Delcy Rodríguez remarked the remaining payment of $10 million could not be completed. UBS would not specify further due to legal and regulatory reasons. The Maduro government said for months that it was unable to pay for the COVAX program because of U.S. sanctions. Venezuela expressed interest in the Janssen and Novavax vaccines after the requested shipment of AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccines was never approved by national authorities.[119] In August 2021, those payments were reportedly unblocked, and Venezuela will receive 6.2 million doses of the Sinopharm BIBP vaccine and CoronaVac through the program.[120]

International concern

International concern was raised before the first cases were reported, as Venezuela's health care system has completely collapsed due to the ongoing crisis, meaning its already suffering population is especially vulnerable to the spread of a pandemic.[7]

Per the Global Health Security Index, Venezuela's health system is ranked among the worst in the world in its ability to detect, quickly respond, and mitigate a pandemic.[121] Hospitals are plagued by chronic shortages of supplies, including eye protectors, gloves, masks, and soap.[122] Due to ongoing shortages of resources, hospitals must also constantly deal with chronic lack of staff, thus making the response to treating a large number of infected patients significantly more challenging.[122] Patients are also often turned away at hospitals due to overcrowding, or asked to bring in their own gauze, IV solution, or syringes, while there are often no hygiene facilities like toilets, and power outages are a regular occurrence.[7]

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) said that it would be prioritizing Venezuela alongside Haiti and other Central and South American countries because of "challenges to their health systems."[3]

Associated Press reported that experts are worried that the Venezuelan refugee crisis could worsen the spread of the virus.[9]

Prison system

Reuters reported that Venezuela's notoriously overcrowded and unsanitary prisons could spread the coronavirus "like a fast-moving fire." Venezuelan prisons frequently lack bathrooms, people sleep on floors, and many inmates spend their days without shirts or shoes on, in part to combat the infernal heat of windowless facilities.[123] This has caused US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to demand the Maduro government release six Citgo executives, held in prison since 2017, on humanitarian grounds.[124][125] Pompeo said that all six men have weakened immune systems and "face a grave health risk if they become infected" with the coronavirus pandemic.[125]

On 18 March, 84 out of 518 inmates escaped from a prison in San Carlos, Zulia, after restrictions against the pandemic were announced, including jail visits. Mayor Bladimir Labrador declared that ten prisoners were killed during the prison break and that two policemen were detained for complicity. According to Carlos Nieto Palma from the NGO Ventana a la Libertad, the suspension of visits directly affects the prisoner's nutrition, given that there was no state-sponsored program to feed them.[126] The NGO PROVEA denounced "grave human rights violations" after a military spokesperson announced the "neutralization" of 35 escapees. State authorities later declared that there were eight deaths.[127]

Hearing over the Esequibo

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) planned to discuss Guyana and Venezuela border dispute over Guayana Esequiba in March 2020. The hearing was postponed due to the pandemic.[128] In April, Guyana reported cases of COVID-19 in the disputed territory.[129]

The first hearing was finally carried out on 30 June 2020, but Venezuela did not participate saying that the ICJ lacked jurisdiction. The hearing was held by video conference due to the pandemic.[130]

Economic impact

As a result of the pandemic's economic impact, some businesses have sought to supplement lost business with deliveries, though exact figures remain obscure and the services are prohibitively costly for average Venezuelans. Some have started to make deliveries to support their families using bicycles instead of motorcycles due to gasoline shortages.[131]

Misinformation by authorities

In a national broadcast on 27 February 2020, Nicolás Maduro warned that COVID-19 may have been a US-made biological weapon aimed against China, without providing any evidence.[132][133]

Maduro has supported in social media the use of infusions as a cure to COVID-19.[134] Twitter deleted a tweet of Maduro in March that cited the works of Sergio Quintero, a Venezuelan doctor that claims to have found an herbal antidote against COVID-19.[134] Quintero also claims that the virus was created by the United States as a biological weapon.[135] The works were also posted in Facebook and government webpages and shared by thousands of users.[134] The Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research refuted Quintero's claims.[135] Agence France Presse has fact checked this information and has cataloged Quintero's works as misleading and false, no natural cure has either been approved by other specialists nor by the World Health Organization.[134][135]

Maduro's administration has authorized and supported the use of chloroquine and interferon alfa-2b at large scale as treatments for COVID-19.[136] Interferon alfa-2b is an antiviral that has been used in China and has been promoted by Cuba, sometimes as a "vaccine".[137] Both chloroquine and interferon have not been proven to be effective against the disease.[136][137] Chloroquine is an antimalarial drug that can cause cardiac problems if abused.[136]

Throughout March and July 2020, Maduro and his administration have accused Colombia of promoting the "intentional infection" of Venezuelan migrants that returned to their country, saying they were "biological weapon" and threatening them with quarantine. Local authorities have repeated the accusations since.[138][139][140] Maduro administration has given the hypothesis of a "Colombian virus", that would be a more aggressive strain of the virus, to explain the increase in numbers in neighboring Zulia state, but no medical evidence has been provided.[141]

Maduro notified the Pan American Health Organization in October 2020, that a molecule that nullifies the replication capacity of the new coronavirus had been discovered, yet no proof was ever disclosed.[142]

In early 2021, Nicolás Maduro started promoting Carvativir, a thyme-based oral medication that he said was tested on patients in Caracas and neutralizes COVID-19 with no side effect.[143] He described the drug as "tears of José Gregorio Hernández", a 19th-century Venezuelan doctor beatified in 2020.[143] Francisco Marty, an infectious diseases expert at Brigham and Women's Hospital said that the claims about the efficiency of drug effects were unsubstantiated.[143] David Boulware, professor of medicine and an infectious diseases physician at the University of Minnesota Medical School, noted the lack of scientific data.[142] Venezuela's National Academy of Medicine stated that Carvativir had therapeutic potential against coronavirus but warned that, according to international protocols, more data was needed to consider it an anti-COVID-19 medication.[142][143]

In March 2021, Nicolás Maduro Facebook page was frozen for violating policies against spreading misinformation about the coronavirus of the website.[144]

Concerns with government estimates

The official reports have not always been consistent, presenting errors such as missing states, numbers that do not match and inconsistencies with the published estimates.[145][146][147][148] The government keeps a centralized system and does not authorize private clinics and universities to access the tests processing.[149]

The government receives many tests kits from China. Early May, the Maduro administration reported to have performed over 400,000 tests, the largest number of tests in South America at the time.[150] Many of these tests are unreliable rapid tests, raising the possibility of a large number of false positives and negatives.[151]

As of 17 April, only the laboratory of the National Institute of Hygiene (INH) was certified to analyze COVID-19 tests.[149] It is estimated that the INH only has the capacity to analyze 100 samples per day.[149] The current virology team consists of three technicians, working on aging equipment.[149] In comparison, Colombia has 38 certified labs.[149] The government does not allow universities or private clinics to test, even if they have the capacity to do so. Due to lack of transparency, even some top health officials do not know how fast the epidemic is spreading.[149] According to health workers that disclosed information to Reuters, the government is prioritizing sectors that are allied with the United Socialist Party of Venezuela.[149]

The Maduro administration was reporting an average of less than a dozen cases daily until the last weeks of May,[151] a very low number compared to other countries in South America.[151] Human Rights Watch and Johns Hopkins University published that Venezuela's hospitals were "grossly unprepared" and most hospitals lack running water.[151] The American director from Human Rights Watch indicated that "Maduro's statistics are absolutely absurd," in a country "where doctors do not even have water to wash their hands."[151] Kathleen Page from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine involved in the report said that some of the health official interviewed stated "that even when they see confirmed cases of Covid-19 they are not being reported in the epidemiological reports".[152]

Many Venezuelans are skeptical of the government statistics due to the Maduro administration's history of hiding numbers.[151]

Juan Guaidó has questioned the veracity of the official number of cases, stating that there are inconsistencies in the estimates given.[153] In an interview with El Nuevo Herald on 22 March, Guaidó declared that the number of confirmed cases in Venezuela could be more than two hundred, according to opposition estimates, contrary to the 70 cases that Maduro's administration recognized at the moment. El Nuevo Herald reported that internal sources extraofficially confirmed that estimate, that according to said sources there were 181 confirmed cases on the morning of 21 March and a total of 298 in observation.[154]

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, when discussing Cuba, North Korea, Venezuela and Zimbabwe, called for the easing of sanctions to enable their medical systems to combat COVID-19.[155] These countries should provide transparent information and accept offers of humanitarian help when needed, according to Bachelet.[155] She also said that Venezuela suffers from many kind of supply and technical shortages, that pre-date the sanctions.[155] She also called Venezuelan government to protect health workers saying that they "should never be punished by the authorities for pointing out deficiencies in the response to the crisis."[155]

Non-government estimates

Four cases were extraofficially reported in El Helicoide on 18 March 2020, three women and a male officer of the motorized brigade of the National Police.[156][157]

A person self-identified as a member of the Tupamaro colectivo in the 23 de Enero parish of Caracas declared to his community with a megaphone that a case was confirmed on 19 March 2020, specifically in Block 39, asking his neighbors to stay home and to prevent other blocks from being infected.[158][159]

Venezuelan newspaper El Nacional, reported a total of 65 cases for 20 March, according to undisclosed sources from the Health Ministry.[160] On that day the ministry did not report any official numbers, the toll was officially updated the next day going from 42 to 70.[161] Similarly, before the official report on 23 March, El Nacional reported 84 cases according undisclosed source from the Health Ministry.[162]

The Academy of Physical, Mathematical and Natural Science (Spanish: Academia de Ciencias Físicas, Matemáticas y Naturales) warned that on 2 April the epidemiological curves of Venezuela were unusual, saying that there was just a linear increase of accumulated confirmed cases, a pattern that is atypical for the initial phase of COVID-19 outbreaks.[163]

Physician and opposition deputy, Jose Manuel Olivares, said Maduro's administration has concealed at least four COVID-19 deaths from the 10 it has made public up to 27 May 2020.[151] Two of these extra cases had received PCR tests that resulted positive after their death, but were not counted in the official reports.[164]

Authorities' actions on reporting

On 13 March, Delta Amacuro indigenous leader and journalist Melquiades Ávila, who has criticized health infrastructure in the country, questioned publicly through Facebook "will our hospital be ready for coronavirus?" and ridiculed Maduro's claim that 46 hospitals were prepared for COVID-19. The Governor of Delta Amacuro Lizeta Hernández and member of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, sent the state army to detain Ávila. When asked why by Reuters on the matter, she said that it was to "orient" Ávila and ensure he was being "serious and responsible".[165]

An opposition lawmaker, Tony Geara, was arrested on 14 March in a roadblock after declaring that there was no running water in one of the hospitals listed as prepared by the Bolivarian government.[165] A court charged Geara with illegal possession of explosives and weapons. Geara denies the charges.[165]

According to twelve medical workers interviewed by Reuters, security forces use roadblocks and checkpoints to shakedown medical staff.[165]

Julio Molinos, a medical union leader and retired technician, published a video asking the government to be transparent about hospital conditions on 15 March. Special Action Forces (FAES) arrested Molinos, who was sentenced to house arrest on charges of conspiracy and inciting hatred.[165]

The National Assembly released a webpage to provide information and health recommendations on COVID-19 but the access to the website was restricted by CANTV, the state internet provider. The censorship was denounced by Guaidó.[166]

Iván Virgüez, a 65-year-old human rights lawyer was arrested in April for criticizing the conditions of quarantine centers for migrants returning to Venezuela. He reports to the Human Rights Watch to have been handcuffed for two hours under the sun to a metal tube 2 feet off the ground and was denied a bathroom for 26 hours.[167] Virgüez was later held under house arrest, charged with public disturbance, contempt, defamation of authorities and instigation of rebellion.[167]

According to a Human Rights Watch report, healthcare worker Andrea Sayago was coerced to resign after the photos she shared of their first coronavirus cases through WhatsApp, a private messaging service, were leaked through social media in April. Her photos were described as "terrorism" and she was charged with misuse of privileged information.[167]

Arrest of Darvinson Rojas

On the night of 21 March 2020, journalist Darvinson Rojas was arrested at his home in Caracas by officials of the Bolivarian National Police (PNB) and around fifteen armed personnel from the Special Actions Force (FAES).[168][169] According to the National Union of Press Workers (SNTP), the arrest was related to the coverage of Rojas with his recent publications on the COVID-19 situation in Venezuela.[170]

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) called for the immediate release of Rojas. Nathalie Southwick, CPJ coordinator, stated that "Violently detaining a journalist and interrogating him about his sources on a vital public health issue like the COVID-19 outbreak has an undeniable chilling effect that will only discourage other journalists from reporting on the pandemic."[171] Amnesty International demanded Rojas immediate and unconditional release.[172]

The SNTP, on 24 March, denounced that Darvinson was presented in the tribunals "illegally" and "clandestinely".[173]

After 12 days incarcerated, Darvinson Rojas was set free on 3 April 2020 under precautionary measures.[174]

Backlash on Venezuelan scientific report

Venezuela's Academy of Physical, Mathematical and Natural Science published an estimate of the future cases in Venezuela in May 2020. The report predicts that the number of infected in Venezuela could reach 4000 cases sometime in June.[175] The report also states that the number of deaths reported so far were inconsistent with the epidemic.[175] The academy called for an increase in the number of PCR tests and raised concerns of the difficulty of flattening the curve under the current conditions.[176][175]

Diosdado Cabello, vice-president of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela and president of pro-government Constituent National Assembly, criticized the academy for provoking "terror" in the population, discredited the academy report and demanded security forces to investigate its researchers. The academy answered by saying "it worries us as scientists, that we are harassed and marked for a technical report intended to improve management of the pandemic."[176][175] The National Assembly defended the academy and answered that "Providing scientific facts in an unbiased way for the well-being of our people who are suffering the worst crisis in our history, is a heroic act that deserves to be recognized by all Venezuelans."[175]

Human Rights Watch report

In an August 2020 report, Human Rights Watch described how the Venezuelan government had used the pandemic to control and crackdown on journalists, healthcare workers, human rights lawyers and political opponents that are critical to the government response. The report listed 162 alleged cases of physical abuse and torture committed by the authorities between March and June, corroborated through interviews with the victims, media reports and human rights advocate groups.[167]

Statistics

Cumulative number of cases and recoveries

Notes:

- There was no official report on 20 March 2020, Worldometer[177] and the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) of the Johns Hopkins University reported 65 cases, numbers coming from an article of El Nacional from undisclosed sources from the Venezuelan Ministry of Health.[160]

- The recoveries from 21 March to 25 March indicate people without symptoms for at least 5 days, considered as recovered in the official reports.

Daily new cases

Cumulative number of deaths

Daily deaths

Regional distribution

Cases per federal entity touched by the pandemic, as of 29 September 2021:[178]

| Federal entity | Number of reported cases[178] |

|---|---|

| 2,101 | |

| 10,125 | |

| 12,566 | |

| 14,493 | |

| 8,936 | |

| 12,755 | |

| 57,344 | |

| 18,339 | |

| 5,830 | |

| 2,231 | |

| 9,835 | |

| 230 | |

| 2,740 | |

| 16,497 | |

| 12,836 | |

| 44,881 | |

| 8,987 | |

| 15,655 | |

| 3,934 | |

| 9,125 | |

| 13,121 | |

| 5,293 | |

| 20,465 | |

| 28,865 | |

| 28,966 | |

| Total | 366,150 |

Various Venezuelan newspapers have pointed out that there have been some inconsistencies with the government reports by federal states.[179][180][181][182] For example, 24 March report differs from 23 report, as Táchira and Portuguesa that reported cases before, were no longer included.[182] On 26 March, while the official report indicated 107 total cases, the number of cases per dependency amounted to 108.[179]

In April, the Ministry of Public Health of Guyana confirmed patients with coronavirus in Barima-Waini,[129] located in Guayana Esequiba and a territory disputed with Venezuela. These cases are not included in the statistics provided by the Bolivarian Government of Venezuela.

Per origin

As of 16 March, there were 33 confirmed cases in Venezuela. According to official estimates, among these, 28 came from Europe and 5 from Cúcuta, Colombia. Two of the cases consisted of foreign citizens, one of a diplomatic official, while the rest consisted of Venezuelan residents.[24]

By 22 March, Maduro announced out of all the 77 cases were imported.[183] According to him, 43 had traveled recently, the distribution was as follows:[183]

| Country | Number of imported cases |

|---|---|

| 2 | |

| 10 | |

| 3 | |

| 3 | |

| 1 | |

| 21 | |

| 3 | |

| Total | 43 |

On 24 March, Maduro first mentioned the existence of cases transmitted locally in the country.[184]

Jorge Rodríguez announced on 15 May that between 70 and 80% of the cases reported in May were from foreign origin.[185]

See also

- COVID-19 pandemic by country

- COVID-19 pandemic in South America

- 2009 flu pandemic in Venezuela

- 2019 shipping of humanitarian aid to Venezuela

Footnotes

- The only affected federal dependency is Los Roques

References

- "Coronavirus en Venezuela: cuatro fallecidos y 492 casos nuevos este #14Nov". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). 8 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- "Régimen de Maduro confirma dos primeros casos de coronavirus". NTN24.com (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Venezuela confirms coronavirus cases amid public health concerns". Reuters. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Venezuela confirms first coronavirus death: official". Reuters. 26 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- María Victoria Fermín (29 March 2020). "Tercer fallecido por coronavirus en el país era un taxista de Antímano". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Souquett Gil, Mariana (1 April 2020). "De marzo a febrero: versiones sobre la llegada del coronavirus a Venezuela". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "Venezuela Conducts 'Tens' of Virus Tests and Bans Europe Flights". Bloomberg. 12 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Duque ordena cerrar los pasos fronterizos con Venezuela". El Tiempo (Anzoátegui) (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Smith, Scott (13 March 2020). "Venezuela, already in crisis, reports 1st coronavirus cases". Associated Press. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "Brazil partially closing Venezuela border, allowing trucks". Reuters. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Dinero (26 August 2020). "Fronteras de Colombia se mantendrán cerradas en septiembre". ¿Cuándo se abrirán las fronteras terrestres en Colombia? (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- "Venezuela has fully vaccinated around 10% of its population, doctors group says". Reuters. 2 September 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- "Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of): WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data". covid19.who.int. WHO. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- "Venezuela: the latest coronavirus counts, charts and maps". Reuters. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- Souquett Gil, Mariana (31 January 2020). "Venezuela sin kits de diagnóstico ni condiciones para enfrentar el nuevo coronavirus". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Venezuela imposes entry restrictions over coronavirus". Prensa Latina. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Omar Prieto pide investigar a profesor por denunciar casos sospechosos de coronavirus". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). 9 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "Detectan un caso sospechoso de Coronavirus en Maracaibo". Fe y Alegría (in Spanish). 7 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Digital, Periodista (12 March 2020). "El sátrapa Nicolás Maduro prohíbe las manifestaciones en su contra "para evitar el coronavirus"". Periodista Digital (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "Jorge Rodríguez confirma ocho nuevos casos de coronavirus en Venezuela" (in Spanish). El Caraboreño. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Torrealba, Diego (14 March 2020). "Suben a 10 los casos por coronavirus en Venezuela". El Pitazo (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Venezuela orders 'collective quarantine' in response to coronavirus". Reuters. 15 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Embajador de Argentina en Venezuela contrajo coronavirus". El Nacional (in Spanish). 16 March 2020.

- "Maduro confirma 33 casos de coronavirus en Venezuela y ordena "cuarentena total" #16Mar". Runrunes (in Spanish). 17 March 2020.

- "Quarantine threatens to deepen Venezuelan crisis as roadblocks snarl food supplies". Reuters. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Paciente portador de COVID-19 huyó de CDI en Propatria donde permanecía aislado". El Carabobeño (in Spanish). 19 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Paciente con coronavirus huye del hospital en Caracas". Diario Las Américas (in Spanish). 19 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Delcy Rodríguez: No se confirmaron nuevos casos de coronavirus en las últimas 24 horas". El Nacional (in Spanish). 18 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "Venezuela usará cuartos de hotel para aislar casos suaves de coronavirus: ministro – Reuters". Reuters (in Spanish). 21 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "Venezuela prohibits company layoffs and suspends credit collections over coronavirus". Reuters. 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Fuentes, Federico (1 April 2020). "Venezuela: Combatting COVID-19 through solidarity". Green Left. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- Rodríguez Rosas, Ronny (27 March 2020). "Segunda muerte por COVID-19 y suben a 113 los contagiados". Efecto Cocuyo. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Venezuela reporta segunda muerte por COVID-19, casos ascienden a 113 en el país". Reuters (in Spanish). 27 March 2020. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Prime Minister Meets with Venezuelan Vice President". gov.tt. 27 March 2020.

- Sarmiento, Mabel (27 March 2020). "En Lara la GNB somete a cuarentena forzosa a más de 60 personas que regresaron de Cúcuta". Crónica Uno (in Spanish).

- "Provea: Aislan a 90 personas de manera forzosa en Barquisimeto". El Carabobeño (in Spanish). 27 March 2020.

- "ONG denuncia "confinamiento forzado" de 90 venezolanos por COVID-19". Diario las Américas (in Spanish).

- Leonett, Vanessa (11 April 2020). "Jorge Rodríguez: Venezuela no reporta nuevos casos de COVID-19 este #11abril". El Pitazo (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Ibis León (11 April 2020). "Rodríguez asegura que en Venezuela se hacen "25.000 pruebas diarias" para COVID-19". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Venezuela extiende 30 días más el estado de alarma y cuarentena por coronavirus – Reuters". Reuters (in Spanish). 12 April 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Venezuela impone nuevo toque de queda en una isla por salto de casos de coronavirus – Reuters". Reuters (in Spanish). 19 April 2020. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Maria Souquett Gil (19 April 2020). "Venezuela reporta 29 casos nuevos y decreta toque de queda en Nueva Esparta #19Abr". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "Venezuelan man shot dead amid protests over shortages, NGO says". Reuters. 24 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Primer muerto en Venezuela durante los saqueos y protestas por el hambre". El Mundo (in Spanish). 23 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Shari Avedaño (10 May 2020). "Cifra de personas con COVID-19 en Venezuela llega a 414 este #10May". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Ronny Rodríguez (12 May 2020). "Maduro extiende alarma nacional por un mes más y anuncia un caso de COVID-19". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Ronny Rodríguez (12 May 2020). "Inac extienden hasta el 12 de junio restricción de vuelos nacionales". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Rodríguez Rosas, Ronny (13 May 2020). "Se reportan 17 nuevos casos de coronavirus en Venezuela este #13May". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Sánchez, Fabiola (26 June 2020). "Virus hits Venezuelan city, raising fears of broader crisis". Associated Press. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Casos de coronavirus en Venezuela: un muerto y 34 nuevos contagios este #26May". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). 26 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Carvajal, Johnny (17 June 2020). "Some Venezuelans welcome relaxing of lockdown after 14 weeks inside". Reuters. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Hundreds of Venezuelans camp in northern Bogota, await return home". Reuters. 9 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Gobierno de Maduro extiende estado de alarma por un mes más". Efecto Cocuyo. 12 June 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Venezuela socialist party boss announces he has COVID-19". AP NEWS. 9 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- "Venezuela oil minister El Aissami tests positive for COVID-19". Reuters. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- "Governor of Venezuela's capital district, key Maduro ally, dies of COVID-19". Reuters. 13 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "Close adviser to Venezuela's president has coronavirus". Associated Press. 13 August 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Venezuela kicks off Covid vaccine program". au.news.yahoo.com. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "Venezuela won't authorise AstraZeneca vaccine due to safety fears". www.aljazeera.com. 16 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "Vacuna AstraZeneca: Guaidó la compra y Maduro la prohíbe". El Estímulo (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- "Venezuelan students return to class after COVID-19 closures". Aljazeera. 25 October 2021. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Venezuela's Maduro suspends flights from Europe, Colombia over coronavirus concerns". Reuters. 12 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Gobierno convoca a viajeros del vuelo 6673 presentarse para cumplir la cuarentena". El Pitazo (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "Anuncian suspensión de clases tras llegada del Coronavirus a Venezuela". Noticias de Venezuela y el Mundo – Caraota Digital (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Reverol: "No puede entrar ninguna persona al territorio nacional sin tapabocas"". Panorama (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Dos detenidos por difundir información falsa sobre el Covid 19". El Universal (Caracas) (in Spanish). 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Sudeban informó que actividades bancarias estarán suspendidas desde el lunes (+Comunicado)". El Tiempo (Anzoátegui) (in Spanish). 15 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "Padrino López: Fuerza Armada controlará acceso a los estados en cuarentena". El Pitazo (in Spanish). 16 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- "Maduro le pide al FMI 5 mil millones de dólares para actuar contra el COVID-19". EFE (in Spanish). eldiario.es. 17 March 2020.

- Berwick, Angus (17 March 2020). "Quarantine threatens to deepen Venezuelan crisis as roadblocks snarl food supplies". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- "Venezuela seeks emergency $5 billion IMF loan to fight virus". AP NEWS. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- "Venezuela Requests $5 Billion from IMF to Fight Coronavirus". Bloomberg.com. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- "IMF rejects Maduro's bid for emergency loan to fight virus". AP NEWS. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Vasquez, Alex (21 March 2020). "Rejected Venezuela Returns to IMF Seeking $1 Billion in Aid". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Venezuela lifts coronavirus cases to 42, thanks China for aid". Reuters. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Fermín Kancev, María Victoria (20 March 2020). "Maduro: Rusia enviará ayuda humanitaria a Venezuela por el coronavirus". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Ariza, Joselyn (23 March 2020). "Rusia envía insumos médicos a Venezuela para detectar Covid-19" (in Spanish). Venezuelan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Maduro, Nicolás [@NicolasMaduro] (23 March 2020). "Llegaron a Venezuela 10 mil kits de pruebas diagnósticas procedentes de la Federación de Rusia para el despistaje del COVID-19. En nombre de nuestro pueblo, agradezco la solidaridad y la cooperación del hermano Presidente Vladímir Putin y del pueblo ruso. ¡Un Abrazo! t.co/snyYnzjwWT" (Tweet) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022 – via Twitter.

- Hernández, Erika (23 March 2020). "Medidas económicas populistas anunciadas por Maduro podrían enterrar al sector privado". El Nacional (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Reuters Staff (2 October 2020). "Venezuela receives shipment of Russian Sputnik-V coronavirus vaccine". Reuters. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- Reuters Staff (29 December 2020). "Venezuela signs contract with Russia to acquire coronavirus vaccine". Reuters. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "Doctors Without Borders ends COVID care in Venezuela clinic". AP NEWS. 25 November 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- "Guaidó anunció una redefinición de la agenda de protestas por el coronavirus: "Es momento de que el régimen deje entrar la ayuda humanitaria"". Infobae (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Rodríguez Rosas, Ronny (13 March 2020). "Guaidó anuncia redefinición de las convocatorias de calle por el coronavirus". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Murillo, Yuskerli (16 March 2020). "Comité para designar nuevo CNE suspenderá reuniones". El Universal (Caracas) (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Escalona, José (16 March 2020). "Julio Castro: La mascarilla solo sirve para un día, puede ser un foco de infección si se usa varias veces #16Mar". El Impulso (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- "Mil venezolanos recibieron donación de Taiwán para prevenir el coronavirus". La Patilla (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Berwick, Angus (17 March 2020). "Venezuela expands quarantine as number of coronavirus cases climbs to 33". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- "EN VIDEO: Guaidó entrega kits para proteger al sector salud del brote de coronavirus". La Patilla (in Spanish). 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Guaidó, Juan [@jguaido] (21 March 2020). "Estamos protegiendo a un sector que hoy está dándolo todo: el sector salud, nuestros médicos y enfermeras. Apoyarlos es apoyarnos todos. Esta ayuda debemos llevarla a cientos que la necesitan. Podemos contener esta emergencia. Venezuela está en nuestras manos. #AuxilioParaVzla t.co/iUpXnWmpJf" (Tweet) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2022 – via Twitter.

- "Guaidó denuncia un aumento de las violaciones de los DDHH en Venezuela desde el estallido de la pandemia". Europa Press (in Spanish). 23 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Goodman, Joshua (29 March 2020). "Guaido urges unity government backed by loans to fight virus". Associated Press. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "U.S. unfreezing Venezualan assets to help opposition fight COVID-19: Guaido". Reuters. 21 August 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- Sequera, Brian Ellsworth, Vivian (12 November 2020). "Funds seized in U.S. help Venezuela health workers survive crisis". Reuters. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Smith, Scot (3 June 2020). "Virus forges rare accord among bitter Venezuelan rivals". Associated Press. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Reuters Staff (22 January 2021). "Venezuelan opposition says Maduro government violated COVID response agreement". Reuters. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Suspendieron actividades eclesiásticas en Venezuela tras brote de coronavirus". VPItv (in Spanish). 15 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Fern Rodríguez, María (18 March 2020). "Laboratorio de microbiología de la ULA hará pruebas para detectar coronavirus". El Pitazo (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Galaviz, Daisy (23 March 2020). "Colectivos imponen toque de queda en el 23 de Enero por el coronavirus". El Pitazo (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Familiares señalan colectivos por asesinato tres vecinos del 23 de Enero". El Pitazo (in Spanish). 22 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Maduro pide no politizar el tema del coronavirus mientras apunta el dedo a los EEUU y la oposición (VIDEOS)". Entorno Inteligente (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Laya, Patricia (12 March 2020). "Venezuela Conducts 'Tens' of Virus Tests and Bans Europe Flights". Bloomberg. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "FMV denunció amedrentamiento a médicos tras estado de alarma por coronavirus". La Patilla (in Spanish). 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Presidente de la FMV exhorta a que se liberen a presos políticos por coronavirus". La Patilla (in Spanish). 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Pellicani, Giovanna (16 March 2020). "Enfermeras denuncian falta de mascarillas, guantes y bata desechable en Anzoátegui". El Pitazo (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- "Transparencia Venezuela exige información veraz". Runrun.es (in Spanish). 7 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Villarreal, Karina (13 March 2020). "Coronavirus en Venezuela: encarecimiento de las mascarillas". El Nacional (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus en Venezuela: $ 140 mil por caja de tapabocas". El Tiempo (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Tapabocas desechables se elevan de 7.000 a 80.000 bolívares tras confirmación de coronavirus". Diario Versión Final (in Spanish). 13 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Brito, Estefani (26 March 2020). "La necesidad obliga: el pueblo en la calle a pesar de la cuarentena". El Nacional (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Embajada virtual de EEUU en Venezuela se las cantó clarito a Maduro tras llorantina por sanciones". La Patilla (in Spanish). 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Embajador James "Jimmy" Story [@usembassyve] (13 March 2020). "Medicinas, insumos médicos, piezas de repuesto y componentes para productos sanitarios en Venezuela, o a personas de terceros países que compran específicamente para reventa a Venezuela quedan excluidos de las sanciones estadounidenses. Para que sepan @NicolasMaduro @jaarreaza" (Tweet) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2022 – via Twitter.

- "Jorge Arreaza: bloqueo económico contra Venezuela afecta adquisición de insumos". Diario 2001 (in Spanish). Agencia Venezolana de Noticias. 21 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Pitazo, Redacción El (16 March 2020). "Ortega Díaz: Maduro miente al decir que no hay medicinas por las sanciones". El Pitazo (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Nichols, Brian [@WHAAsstSecty] (19 March 2020). "More lies from #Maduro, author of the #MaduroCrisis, about #Venezuela's tragedy. U.S. sanctions NEVER block food or medicine. Shortages in Venezuela result from the regime's theft of the nation's wealth. #EstamosUnidosVE" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2022 – via Twitter.

- "Kozak reiteró que las sanciones de EEUU al régimen de Maduro 'no bloquean comida o medicinas'". AlbertoNews (in Spanish). 20 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "Ease sanctions against countries fighting COVID-19: UN human rights chief". UN News. 24 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Bachelet calls for easing of sanctions to enable medical systems to fight COVID-19 and limit global contagion". ReliefWeb. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Venezuela says payments to COVAX vaccine system have been blocked". Reuters Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- "Venezuela to receive COVAX vaccines in coming days, Maduro says" Reuters. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- "2019 Global Health Security Index" (PDF). 22 October 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Buckets for toilets, recycled gloves: Venezuelan hospitals await coronavirus unprepared". Reuters. 10 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Ellsworth, Brian; Sequera, Vivian (18 March 2020). "Overcrowded and unsanitary, Venezuela's prisons brace for coronavirus". Reuters. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Pompeo, Mike [@SecPompeo] (19 March 2020). "It is past time for the Maduro regime to release the #Citgo6 who are currently languishing in the notorious Helicoide prison in #Venezuela. 2+ years in prison with no evidence brought against them; 18 hearings cancelled. Unacceptable" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022 – via Twitter.

- "US demands Venezuela free Citgo executives as virus hits". France 24. Agence France-Presse. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- "Las restricciones por el coronavirus provocan una fuga de presos que deja 10 muertos en Venezuela". El Mundo (in Spanish). AFP. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Provea denuncia asesinato de 35 presos fugados de retén en Zulia". Tal Cual (in Spanish). 18 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Guyana: Hearing of border controversy matter postponed". St. Lucia News Online. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Joseph, Sharine (8 April 2020). "Guyana: 33 test positive for COVID-19". St. Lucia News Online. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Venezuela boycotts UN court hearing on Guyana border row". The Jakarta Post. Agence-France Presse. 1 July 2020.

- "For struggling Venezuelans in quarantine, an opportunity in delivery services". Reuters. 16 April 2020.

- Wyss, Jim (28 February 2020). "As coronavirus lands in Latin America, Venezuela's Maduro amps up conspiracy theories". Miami Herald. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Fisher, Max (8 April 2020). "Why Coronavirus Conspiracy Theories Flourish. And Why It Matters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Según expertos, el "remedio" con saúco, jengibre, pimienta y miel que difundió el presidente de Venezuela no cura el COVID-19". AFP Factual (in Spanish). 25 March 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Gutierrez, Jeanfreddy (25 March 2020). "¿Quién es Sirio Quintero, el "científico" antivacunas que Maduro respaldó?". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Torres del Cerro, Antonio (22 May 2020). "Bolsonaro y Maduro, dos líderes enfrentados unidos por la cloroquina". Agencia EFE (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "El antiviral cubano Interferón Alfa 2B se usa en China para tratar a enfermos del nuevo coronavirus, pero no es ni una vacuna ni una cura". AFP Factual (in Spanish). 18 March 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "El Gobierno de Maduro llama 'armas biológicas' a venezolanos retornados y amenaza con recluirlos en cuarentena". El Comercio. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Herrero, Ana Vanessa; Faiola, Anthony; Zuñiga, Mariana (19 July 2020). "As coronavirus explodes in Venezuela, Maduro's government blames 'biological weapon': the country's returning refugees". The Washington Post.

- "Returning home, Venezuelans face accusations of spreading COVID-19". Reuters. 20 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Sequera, Vivian (15 July 2020). "Venezuela coronavirus cases spike, opposition warns healthcare system may be overwhelmed". Reuters. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Maduro's 'miracle' treatment for COVID-19 draws skeptics". AP NEWS. 26 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Doctors skeptical as Venezuela's Maduro touts coronavirus 'miracle' drug". Reuters. 26 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Venezuela: Facebook freezes Maduro's page over COVID misinformation". Deutsche Welle. 27 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "Cifras de coronavirus presentadas por el gobierno de Maduro revelan incongruencias". Runrun (in Spanish). 20 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "¿"Importados" o locales?, contradicciones del chavismo en torno a los casos de COVID-19". Efecto Cocuyo. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Maduro informa que se elevan a 91 contagios de COVID-19 y dice que "hay casos comunitarios"". Efecto Cocuyo. 25 March 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Delcy Rodríguez confirma primer fallecido por Covid-19". Runrun (in Spanish). 26 March 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "In run-down Caracas institute, Venezuela's coronavirus testing falters". Reuters. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Pruebas rápidas de COVID-19 aplicadas en Venezuela no pasan el examen". Runrunes (in Spanish). 12 May 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Smith, Scott (27 May 2020). "Venezuela's apparent respite from COVID-19 may not last long". Associated Press. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Phillips, Tom (26 May 2020). "Venezuela's Covid-19 death toll claims 'not credible', human rights group says". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Guaidó asegura que hay "incongruencias" en cifras del régimen sobre COVID-19". Diario Las Americas (in Spanish). 23 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Delgado, Antonio María (22 March 2020). "Exclusiva: Maduro oculta gravedad del coronavirus. Hay más de 200 casos en Venezuela, dice Guaidó". El Nuevo Herald. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Bachelet, Michelle (24 March 2020). "OHCHR | Bachelet calls for easing of sanctions to enable medical systems to fight COVID-19 and limit global contagion". OHCR. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Detectaron cuatro casos de coronavirus en El Helicoide". El Nacional (in Spanish). 18 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "Los presos políticos de Venezuela están en riesgo por el coronavirus: se detectaron cuatro casos en la cárcel de El Helicoide". Infobae (in European Spanish). 19 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus Colectivos del 23 de Enero aseguran un caso en el bloque 39". El Pitazo (in Spanish). 20 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "[VIDEO] Tupamaros aseguran que el coronavirus ya llegó al 23 de Enero". El Nacional (in Spanish). 20 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Venezuela registró otros 19 casos de coronavirus este viernes". El Nacional (in Spanish). 23 March 2020.

- "Cifras de coronavirus presentadas por el gobierno de Maduro revelan incongruencias". Runrunes (in Spanish). 20 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "Venezuela registró otros siete casos por coronavirus y la cifra de contagios se elevó a 84". El Nacional (in Spanish). 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Singer, Florantonia (24 April 2020). "Los agujeros del coronavirus en Venezuela". El País. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "José Manuel Olivares denunció que Maduro ocultó cuatro muertes por covid-19". El Nacional (in Spanish). 18 May 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Angus Berwick; Sarah Kinosian; Maria Ramirez (25 March 2020). "As coronavirus hits Venezuela, Maduro further quashes dissent". Reuters. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Fermín, María Victoria (18 March 2020). "Cantv bloquea web informativa sobre el COVID-19, denuncia Venezuela Sin Filtro". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Human Rights Watch: Venezuela using COVID-19 to crack down". Associated Press. 28 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Avendaño, Shari (21 March 2020). "Faes detiene a periodista Darvinson Rojas y su familia, denuncia Sntp" (in Spanish). Efecto Cocuyo. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "Denuncian la detención del periodista venezolano Darvinson Rojas en Caracas" (in Spanish). eldiario.es. EFE. 22 March 2020.

- "Denuncian la detención del periodista venezolano Darvinson Rojas en Caracas" (in Spanish). La Vanguardia. 21 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "Venezuelan journalist arrested by special forces following coronavirus coverage". Committee to Protect Journalists. 22 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Venezuela: Journalist reporting on COVID-19 jailed". Amnesty International. 23 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Sntp: Darvinson Rojas fue presentado en tribunales de manera ilegal y clandestina". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). 24 March 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Venezuela libera a periodista detenido por publicaciones en Twitter sobre COVID-19". Deutsche Welle (in Spanish). 3 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Venezuela scientists face government backlash for research predicting surge in COVID-19 cases". Reuters. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Rodríguez Rosas, Ronny (14 May 2020). "Academia de Ciencias rechaza amenazas de Diosdado Cabello". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "Venezuela Coronavirus: 197 Cases and 9 Deaths – Worldometer". Worldometer. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Estadísticas Venezuela". COVID-19 en Venezuela PATRIA blog (Gobierno Bolivariano de Venezuela) (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Delcy Rodríguez confirma primer fallecido por Covid-19". Runrun (in Spanish). 26 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Cronología de incongruencias y opacidad en cifras oficiales de Covid-19 en Venezuela". Runrunes (in Spanish). 26 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Avendaño, Shari (19 March 2020). "¿"Importados" o locales?, contradicciones del chavismo en torno a los casos de COVID-19". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Rodríguez Rosas, Ronny (25 March 2020). "Maduro informa que se elevan a 91 contagios de COVID-19 y dice que "hay casos comunitarios"". Efecto Cocuyo (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Maduro anunció que cifra de contagiados por Covid-19 aumentó a 77". Runrun.es (in Spanish). 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.