Timeline of influenza

This is a timeline of influenza, briefly describing major events such as outbreaks, epidemics, pandemics, discoveries and developments of vaccines. In addition to specific year/period-related events, there's the seasonal flu that kills between 250,000 and 500,000 people every year, and has claimed between 340 million and 1 billion human lives throughout history.[1][2]

Overview

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| Before the 16th Century | The outbreak of influenza reported in 1173 is not considered to be a pandemic, and other reports to 1500 generally lack reliability. |

| 16th Century | The 1510 influenza pandemic spread from Asia to Africa, then engulfing Europe. It is the first documented case of intercontinental spread of an influenza virus, with less lethality than future pandemics.

The 1557 influenza pandemic spread from Asia to the Ottoman Empire, then Europe, the Americas, and Africa. This flu pandemic is the first to be reliably recorded as spreading worldwide,[3][4][5][6] is when flu received its first English names.[7][8] It is also the first pandemic in which flu is linked to miscarriages.[9] The pandemic lasted for at least two years.[10][11] The 1580 pandemic is well-documented, with high mortality recorded as influenza spreads across Europe.[12] |

| 18th century | Data from this century is more informative of pandemics than those of previous years. The first agreed influenza pandemic of the 18th century begins in 1729.[12] |

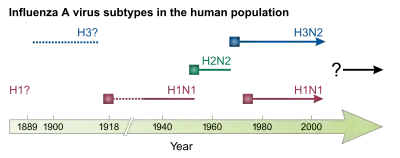

| 19th century | Two influenza pandemics are recorded in the century.[12] Avian influenza is recorded for the first time.[13] |

| 20th century | Influenza pandemics are recorded four times, starting with the deadly Spanish flu. This is also the period of virus isolation and development of vaccines.[14] Prior to 20th century, much information about influenza is generally not considered certain. Although the virus seems to have caused epidemics throughout human history, historical data on influenza are difficult to interpret, because the symptoms can be similar to those of other respiratory diseases.[15][16] |

| 1945 – 21st century | International health organizations merge, and large scale vaccination campaigns begin.[17] |

| 21st century | Worldwide accessible databases multiply in order to control outbreaks and prevent pandemics. New influenza strain outbreaks still occur. Efficacy of currently available vaccines is still insufficient to diminish the current annual health burden induced by the virus.[17] |

Full timeline: Hippocrates - 2017

Influenza has been studied by countless physicians, epidemiologists, and medical historians. Chroniclers distinguished its outbreaks from other diseases by the rapid, indiscriminate way it struck down entire populations. Flu has been called various names including tac,[20] coqueluche,[21][22][23] the new disease,[24] gruppie,[25] grippe, castrone,[26][27] influenza,[28] and commonly just catarrh[29][30][31] by many chroniclers and physicians throughout the ages.

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 BCE | Medical development | The symptoms of human influenza are described by Hippocrates.[32][14] | |

| 1173 | Epidemic | First epidemic, where symptoms are probably influenza, is reported.[12] | Europe |

| 1357 | The term influenza is first used to describe a disease prevailing in 1357.[28][33] It would be applied again to the epidemic in 1386−1387.[34] | Italy | |

| 1386–1387 | Epidemic | Influenza-like illness epidemic develops in Europe, preferentially killing elderly and debilitating persons. This is probably the first documentation of a key epidemiological feature of both pandemic and seasonal influenza.[34] | Europe |

| 1411 | Epidemic | Epidemic of coughing disease associated with spontaneous miscarriages is noted in Paris.[34] The illness is referred to as le tac by some contemporaries.[20] | France |

| 1414 | Epidemic | Another outbreak of flu is recorded in Paris, possibly the first time the disease is referred to as coqueluche. | |

| 1510 | Pandemic | Influenza pandemic develops in Asia and proceedes northward to involve North Africa, then all of Europe. Attack rates are extremely high, but fatality is low and said to be restricted to weaker individuals like children and those who were bled.[34] | Africa, Europe |

| 1557–1558 | Pandemic | Influenza pandemic spreads westward from Asia to Africa and Europe, then travels aboard European ships across the Atlantic Ocean. Another wave in 1558-59 spreads worldwide with devastating effects.[35][3][4][5][6][34] | Eurasia |

| 1580 | Pandemic | [12][34] | Eurasia, Africa |

| 1729 | Pandemic | [16][12][34] | Eurasia |

| 1761–1762 | Pandemic | [34] | Americas, Europe |

| 1780–1782 | Pandemic | [34] | Eurasia |

| 1830–1833 | Pandemic | [12] | Eurasia, Americas |

| 1878 | Scientific development | First descriptions of avian influenza, termed "fowl plague," is recorded by Perroncito in Italy.[36][37][13] | Italy |

| 1889–1892 | Pandemic | [38][34] | Eurasia, Americas |

| 1901 | Scientific development | [37] | |

| 1918-1920 | Pandemic | In March 1918, 48 soldiers die of "pneumonia" during a, outbreak at Fort Riley, Kansas. Flu travels unchecked eastward[39] to New England military bases before traveling across the Atlantic Ocean on crowded military ships to Europe amid World War I. It spread rapidly through European cities, and was nicknamed Spanish flu for the uncensored reporting in Spain, as moving armies spread flu around the world. Spanish flu returns in waves for the next 2 years.[40][41] | Worldwide; originated in the US, some theories suggest France or other countries |

| 1931 | Scientific development | Richard Shope isolates the Influenza A virus from pigs.[42] | |

| 1933 | Scientific development | Shope and his team discover the Influenza A virus.[43][44][45][46] | United Kingdom |

| 1936 | Medical development | [47] | Russia |

| 1942 | Medical development | [46] | |

| 1945 | Medical development | [48] | United States |

| 1946 | Organization | [49][50] | United States (Atlanta) |

| 1947 | Organization | [51] | France (serves worldwide) |

| 1948 | Organization | [52] | |

| 1952 | Organization (Research institute) | [53] | |

| 1957 | Pandemic | [54][55][56][57][34] | China |

| 1959 | Non–human infection | [58] | United Kingdom |

| 1961 | Non–human infection | [59] | South Africa |

| 1963 | Non–human infection | [58] | United Kingdom |

| 1966 | Non–human infection | [58] | Canada |

| 1968-1969 | Pandemic | [34][60] | Eurasia, North America |

| 1973 | Program launch | [46] | |

| 1976 | Epidemic | [61][62] | United States (New Jersey) |

| 1976 | Non–human infection | [58] | Australia |

| 1977 | Epidemic | [62] | Russia, China, worldwide |

| 1978 | Medical development | [46] | |

| 1980 | Medical development | [63] | United States |

| 1983 | Non–human infection | [64] | Ireland |

| 1988 | Infection | [65] | China |

| 1990-1996 | Medical development | [66] | United States |

| 1997 | Infection | [67] | China (Hong Kong) |

| 1997 | Infection | Australia | |

| 1999 | Infection | [62] | China (Hong Kong) |

| 2002 | Infection | [68] | United States |

| 2003–2007 | Infection | [69] | East Asia, Southeast Asia |

| 2003 | Infection | [70] | Netherlands |

| 2004 | Organization | [71] | |

| 2004 | Infection | [72] | Canada |

| 2004 | Infection | [73] | Egypt |

| 2004 | Non–human infection | [74] | United States |

| 2005 | Organization | [75][76] | United States |

| 2005 | Organization | [77][78] | United States (New York City) |

| 2005 | Infection | [79] | Cambodia, Romania |

| 2006 | Organization | [80] | China (Beijing) |

| 2007 | Non-human infection | [81] | Australia |

| 2008 | Scientific development | [82] | Worldwide |

| 2008 | Service launch | [83] | United States |

| 2009 | Pandemic | [84][85][62] | Worldwide |

| 2011 | Non–human infection | [86] | United States |

| 2012 | Scientific development | [87] | |

| 2012 | Scientific project/controversy | [88][89] | Netherlands (Erasmus Medical Center), United States (University of Wisconsin–Madison) |

| 2012 | Medical development | [90] | United States |

| 2013 | Epidemic | [91][92] | China, Vietnam |

| 2013 | Medical development | [93] | United States |

| 2013 | Infection | [94] | China |

| 2015 | Program | [95][96][97] | United States |

| 2017 | Medical development | [98] | United States |

| 2017 | Scientific development | [99] | Finland |

See also

- Influenza

- Timeline of global health

References

- "WHO Europe – Influenza". World Health Organization (WHO). June 2009. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- "Influenza: Fact sheet". World Health Organization (WHO). March 2003. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- Thompson, Theophilus (1852). Annals of Influenza Or Epidemic Catarrhal Fever in Great Britain from 1510 to 1837. Sydenham Society. p. 101.

- Vaughan, M.D., Warren T. (July 1921). "Influenza - An Epidemiologic Study". The American Journal of Hygiene. 1: 19. ISBN 9780598840387.

- Dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences médicales (in French). Paris: Asselin. 1877. p. 332.

- Pease, Franklin; Damas (1999). Historia general de América Latina: El primer contacto y la formación de nuevas sociedades (in Spanish). Paris, France: UNESCO. p. 311. ISBN 978-92-3-303151-7.

- Creighton, Charles (1891). A History of Epidemics in Britain - The type of sickness in 1558. Cambridge, England: The University Press. pp. 403–407.

- The American Journal of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children. New York: W. Wood & Company. 1919. p. 231.

- Threats, Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial; Knobler, Stacey L.; Mack, Alison; Mahmoud, Adel; Lemon, Stanley M. (2005). The Story of Influenza. National Academies Press (US).

- Creighton, Charles (1894). A History of Epidemics in Britain: From the extinction of plague to the present time. Cambridge, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 307–308.

- Rappaport, Steve (2002-04-04). Worlds Within Worlds: Structures of Life in Sixteenth-Century London. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-521-89221-6.

- Potter, C. W. (October 2001). "A history of influenza". J. Appl. Microbiol. 91 (4): 572–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290.

- "History of Avian Influenza". extension.org. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- Lam, Vincent; Lee, Colin (2009-11-17). The Flu Pandemic and You: A Canadian Guide. ISBN 9780307373199. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Beveridge, W I (1991). "The chronicle of influenza epidemics". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 13 (2): 223–234. PMID 1724803.

- Potter CW (October 2001). "A History of Influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–579. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290.

- Vaccine Analysis: Strategies, Principles, and Control. Springer. 2014. p. 61. ISBN 9783662450246.

- "REPORTED CASES OF NOTIFIABLE DISEASES IN THE AMERICAS 1949 - 1958" (PDF). paho.org. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Palese, Peter (2004). "Influenza: old and new threats". Nature Medicine. 10 (12s): S82–S87. doi:10.1038/nm1141. PMID 15577936.

- Blyth, Alexander Wynter (1876). A Dictionary of Hygiène and Public Health: Comprising Sanitary Chemistry, Engineering, and Legislation, the Dietetic Value of Foods, and the Detection of Adulterations, on the Plan of the "Dictionnaire D'hygiène Publique" of Professor Ambroise Tardieu. Edinburgh: Ballantyne, Hanson and Co. p. 316.

- Louis, X. I. I.; Godefroy (1712). Lettres du roi Louis XII et du cardinal Georges d'Amboise: depuis 1504 à 1514 (in French). Foppens. pp. 287–288.

- Brouardel, Paul; Agustin, Gilbert; Girode, Joseph (1895). Traité de médecine et de thérapeutique (in French). Paris: B. Ballière et Fils. p. 363.

- Delorme, Raige (1837). "GRIPPE - IV. Histoire et Literature". Encyclographie des Sciences Médicales. Répertoire Général de Ces Sciences, Au XIXe Siècle. Brussels, Belgium: Établissement Encyclographique. 13: 258–259 – via Google Books.

- Creighton, Charles (1891). A History of Epidemics in Britain - The type of sickness in 1558. Cambridge, England: The University Press. pp. 403–407.

- Karsten, Gustaf (1920). The Journal of English and German Philology. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. p. 513.

- Reynolds, Sir John Russell (1880). A System of Medicine: General diseases and diseases of the nervous system. Philadelphia, PA: H.C. Lea's Son & Company. p. 33.

- Finkler, Ditmar (1898). "Influenza". Twentieth Century Practice - an International Encyclopedia of Modern Medical Practice. 15: 17 – via Google Books.

- Morens, David M.; Taubenberger, Jeffery K. (27 June 2011). "Pandemic influenza: certain uncertainties". Reviews in Medical Virology. 21 (5): 262–284. doi:10.1002/rmv.689. ISSN 1052-9276. PMC 3246071. PMID 21706672.

- Annaes das sciencias e lettras (in Brazilian Portuguese). Lisbon: Typographia da Academia. 1857. p. 302.

- Immerman, H.; von Jurgenson, Th.; Liebermeister, C.; Lenhartz, H.; Sticker, G. (1902). Moore, John (ed.). Encyclopedia of Practical Medicine. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. p. 543.

- Culbertson, M.D., J. C., ed. (1890). The Cincinnati Lancet-clinic. Cincinnati: J.C. Culbertson. p. 52.

- Martin, P; Martin-Granel E (June 2006). "2,500-year evolution of the term epidemic". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (6): 976–80. doi:10.3201/eid1206.051263. PMC 3373038. PMID 16707055.

- A. Mir, Shakil (December 2009). "History of Swine Flu". JK Science. PG Department of Pharmacology, Govt Medical College, Srinagar. 8: 163 – via ProQuest.

- Taubenberger, J.K.; Morens, D.M. (2009). "Pandemic influenza – including a risk assessment of H5N1". Rev Sci Tech. 28 (1): 187–202. doi:10.20506/rst.28.1.1879. PMC 2720801. PMID 19618626.

- Stow, John (1575). A Summarie of the Chronicles of England, from the first coming of Brute into this land, unto this present yeare of Christ 1575 ... Corrected and enlarged, etc. B.L. Richard Cottle and Henry Binneman. p. 501.

- Lupiani, Blanca; Reddy, Sanjay M. (2009-07-01). "The history of avian influenza". Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Special Issue: Avian Influenza. 32 (4): 311–323. doi:10.1016/j.cimid.2008.01.004. ISSN 0147-9571. PMID 18533261.

- "FLU-LAB-NET - About Avian Influenza". science.vla.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Valleron, A.-J. (2010). "Transmissibility and geographic spread of the 1889 influenza pandemic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (19): 8778–8781. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8778V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000886107. PMC 2889325. PMID 20421481.

- American Experience | Influenza: Chapter 1 | Season 10 | Episode 5, retrieved 2021-01-06

- "The Influenza Pandemic of 1918". stanford.edu. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Potter CW (October 2001). "A History of Influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–579. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290.

- Shimizu, K (October 1997). "History of influenza epidemics and discovery of influenza virus". Nippon Rinsho. 55 (10): 2505–201. PMID 9360364.

- Shimizu, K. (1997). "[History of influenza epidemics and discovery of influenza virus]". Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine. 55 (10): 2505–2511. ISSN 0047-1852. PMID 9360364.

- Smith, W; Andrewes CH; Laidlaw PP (1933). "A virus obtained from influenza patients". Lancet. 2 (5732): 66–68. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)78541-2.

- Dobson, Mary. 2007. Disease: The Extraordinary Stories behind History’s Deadliest Killers. London, UK: Quercus.

- "The Evolving History of Influenza Viruses and Influenza Vaccines 1". medscape.com. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- "The Evolving History of Influenza Viruses and Influenza Vaccines 2". medscape.com. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- P. CROVARI; M. ALBERTI; C. ALICINO (2011). "History and evolution of influenza vaccines". Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. Department of Health Sciences, University of Genoa, Italy. 52 (3): 91–4. PMID 22010533.

- Turnock, Bernard J. (2015-07-15). Public Health. ISBN 9781284069426. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Ogunseitan, Oladele (2011-05-03). Green Health: An A-to-Z Guide. ISBN 9781452266213. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Influenza Immunization Campaign". wma.net. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Global Health Timeline". 2014-05-16. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Global influenza virological surveillance". WHO. Archived from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Influenza Pandemics". historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Strahan, Lachlan (1994). "An oriental scourge: Australia and the Asian flu epidemic of 1957". Australian Historical Studies. 26 (103): 182–201. doi:10.1080/10314619408595959. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Epidemics Of Chinese Origin". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Asian flu of 1957". britannica.com. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Avian influenza A(H5N1)- update 31: Situation (poultry) in Asia: need for a long-term response, comparison with previous outbreaks". WHO. Archived from the original on March 7, 2004. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)". Nebraska Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Viboud, Cécile; Grais Bernard, Rebecca F.; Lafont, A. P.; Miller, Mark A.; Simonsen, Lone (2005). "Multinational Impact of the 1968 Hong Kong Influenza Pandemic: Evidence for a Smoldering Pandemic". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 192 (2): 233–248. doi:10.1086/431150. PMID 15962218.

- "Timeline of Human Flu Pandemics". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Pandemic Flu History". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Fluzone". vaccineshoppe.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Influenza Strain Details for A/turkey/Ireland/?/1983(H5N8)". Influenza Research Database. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Guo, YJ; Xu, XY; Cox, NJ (1992). "Human influenza A (H1N2) viruses isolated from China". The Journal of General Virology. 73 (2): 383–7. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-73-2-383. PMID 1538194.

- "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "History of Avian Influenza". extension.org. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- Akey, BL (2003). "Low-pathogenicity H7N2 avian influenza outbreak in Virginia during 2002". Avian Dis. 47 (3 Suppl): 1099–103. doi:10.1637/0005-2086-47.s3.1099. PMID 14575120. S2CID 198160190.

- The Global Strategy for Prevention and Control of H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2007. ISBN 9789251057339. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Stegeman, A; Bouma, A; Elbers, AR; De Jong, MC; Nodelijk, G; De Klerk, F; Koch, G; Van Boven, M. (2004). "Avian influenza A virus (H7N7) epidemic in The Netherlands in 2003: course of the epidemic and effectiveness of control measures". J Infect Dis. 190 (12): 2088–95. doi:10.1086/425583. PMID 15551206.

- Fauci AS (January 2006). "Pandemic influenza threat and preparedness". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (1): 73–7. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050983. PMC 3291399. PMID 16494721.

- "Influenza Strain Details for A/Canada/rv504/2004(H7N3)". Influenza Research Database. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "EID Weekly Updates - Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases, Region of the Americas". Pan American Health Organization. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza". usda.gov. Archived from the original on 20 October 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Shannon Brownlee and Jeanne Lenzer (November 2009) "Does the Vaccine Matter?", The Atlantic

- National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Archived 2009-02-21 at the Wayback Machine Whitehouse.gov Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- "The International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza" (PDF). apec.org. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- "International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza". U.S. State Department. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- "Influenza Strain Details for A/Cambodia/V0803338/2011(H1N1)". Influenza Research Database. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "The International Pledging Conference on Avian and Human Pandemic Influenza Is Successfully Held in Beijing".

- Webster, R. W. (2011). "Overview of the 2007 Australian outbreak of equine influenza". Australian Veterinary Journal. 89: 3–4. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00721.x. PMID 21711267.

- Robin Liechti1, Anne Gleizes, Dmitry Kuznetsov, Lydie Bougueleret, Philippe Le Mercier, Amos Bairoch and Ioannis Xenarios (2010). "OpenFluDB, a database for human and animal influenza virus". Database. 2010: baq004. doi:10.1093/database/baq004. PMC 2911839. PMID 20624713.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Butler, Declan (2013). "When Google got flu wrong". Nature. 494 (7436): 155–156. Bibcode:2013Natur.494..155B. doi:10.1038/494155a. PMID 23407515.

- "Europeans urged to avoid Mexico and US as swine flu death toll rises". 27 April 2009.

- "How vaccines became big business".

- Karlsson, Erik A.; Hon, S.; Hall, Jeffrey S.; Yoon, Sun Woo; Johnson, Jordan; Beck, Melinda A.; Webby, Richard J.; Schultz-Cherry, Stacey (2014). "Respiratory transmission of an avian H3N8 influenza virus isolated from a harbour seal". Nature Communications. 5: 4791. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4791K. doi:10.1038/ncomms5791. PMC 4801029. PMID 25183346.

- Osterholm, MT; Kelley, NS; Sommer, A; Belongia, EA (January 2012). "Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 12 (1): 36–44. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(11)70295-x. PMID 22032844.

- "Scientists condemn 'crazy, dangerous' creation of deadly airborne flu virus". The Guardian. 11 June 2014.

- "Exclusive: Controversial US scientist creates deadly new flu strain for pandemic research". The Independent. 2014-06-30. Archived from the original on 2022-05-07.

- "FDA approves first seasonal influenza vaccine manufactured using cell culture technology". FDA. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- "Avian and other zoonotic influenza". WHO. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "Study says Vietnam at H7N9 risk as two new cases noted". umn.edu. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "FDA Approves Flublok Quadrivalent Flu Vaccine". medscape.com. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Avian influenza A (H10N8)". WHO. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "Real-time influenza tracking with 'big data'". eurekalert.org. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- Lazer, David; Kennedy, Ryan (October 2015). "What We Can Learn From the Epic Failure of Google Flu Trends". Wired. Science. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- "Google Flu Trends". datacollaboratives.org. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- "Researchers build flu detector that can diagnose at a breath, no doctor required". digitaltrends.com. February 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- "Certain anti-influenza compounds also inhibit Zika virus infection, researchers find". sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 6 February 2017.