Pia mater

Pia mater (/ˈpaɪ.ə ˈmeɪtər/ or /ˈpiːə ˈmɑːtər/),[1] often referred to as simply the pia, is the delicate innermost layer of the meninges, the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Pia mater is medieval Latin meaning "tender mother".[1] The other two meningeal membranes are the dura mater and the arachnoid mater. Both the pia and arachnoid mater are derivatives of the neural crest while the dura is derived from embryonic mesoderm. The pia mater is a thin fibrous tissue that is permeable to water and small solutes.[2][3] The pia mater allows blood vessels to pass through and nourish the brain. The perivascular space between blood vessels and pia mater is proposed to be part of a pseudolymphatic system for the brain (glymphatic system).[3][4] When the pia mater becomes irritated and inflamed the result is meningitis.[5]

| Pia mater | |

|---|---|

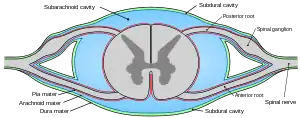

Diagrammatic transverse section of the spinal cord and its membranes. (At border, dura mater is black line, arachnoid mater is blue line, and pia mater is red line.) | |

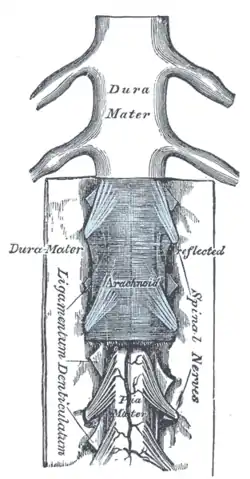

The spinal cord and its membranes | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D010841 |

| TA98 | A14.1.01.301 |

| TA2 | 5405 |

| FMA | 9590 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

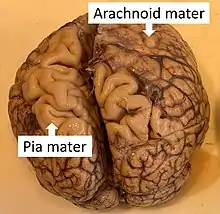

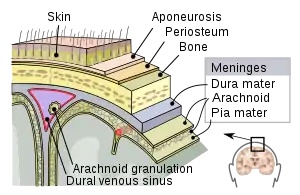

Pia mater is the thin, translucent, mesh-like meningeal envelope, spanning nearly the entire surface of the brain. It is absent only at the natural openings between the ventricles, the median aperture, and the lateral aperture. The pia firmly adheres to the surface of the brain and loosely connects to the arachnoid layer.[6] Because of this continuum, the layers are often referred to as the pia arachnoid or leptomeninges. A subarachnoid space exists between the arachnoid layer and the pia, into which the choroid plexus releases and maintains the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The subarachnoid space contains trabeculae, or fibrous filaments, that connect and bring stability to the two layers, allowing for the appropriate protection from and movement of the proteins, electrolytes, ions, and glucose contained within the CSF.[7]

The thin membrane is composed of fibrous connective tissue, which is covered by a sheet of flat cells impermeable to fluid on its outer surface. A network of blood vessels travels to the brain and spinal cord by interlacing through the pia membrane. These capillaries are responsible for nourishing the brain.[8] This vascular membrane is held together by areolar tissue covered by mesothelial cells from the delicate strands of connective tissue called the arachnoid trabeculae. In the perivascular spaces, the pia mater begins as mesothelial lining on the outer surface, but the cells then fade to be replaced by neuroglia elements.[9]

Although the pia mater is primarily structurally similar throughout, it spans both the spinal cord’s neural tissue and runs down the fissures of the cerebral cortex in the brain. It is often broken down into two categories, the cranial pia mater (pia mater encephali) and the spinal pia mater (pia mater spinalis).

Cranial pia mater

The section of the pia mater enveloping the brain is known as the cranial pia mater. It is anchored to the brain by the processes of astrocytes, which are glial cells responsible for many functions, including maintenance of the extracellular space. The cranial pia mater joins with the ependyma, which lines the cerebral ventricles to form choroid plexuses that produce cerebrospinal fluid. Together with the other meningeal layers, the function of the pia mater is to protect the central nervous system by containing the cerebrospinal fluid, which cushions the brain and spine.[7]

The cranial pia mater covers the surface of the brain. This layer goes in between the cerebral gyri and cerebellar laminae, folding inward to create the tela chorioidea of the third ventricle and the choroid plexuses of the lateral and third ventricles. At the level of the cerebellum, the pia mater membrane is more fragile due to the length of blood vessels as well as decreased connection to the cerebral cortex.[9]

Spinal pia mater

The spinal pia mater closely follows and encloses the curves of the spinal cord, and is attached to it through a connection to the anterior fissure. The pia mater attaches to the dura mater through 21 pairs of denticulate ligaments that pass through the arachnoid mater and dura mater of the spinal cord. These denticular ligaments help to anchor the spinal cord and prevent side to side movement, providing stability.[10] The membrane in this area is much thicker than the cranial pia mater, due to the two-layer composition of the pia membrane. The outer layer, which is made up of mostly connective tissue, is responsible for this thickness. Between the two layers are spaces which exchange information with the subarachnoid cavity as well as blood vessels. At the point where the pia mater reaches the conus medullaris or medullary cone at the end of the spinal cord, the membrane extends as a thin filament called the filum terminale or terminal filum, contained within the lumbar cistern. This filament eventually blends with the dura mater and extends as far as the coccyx, or tailbone. It then fuses with the periosteum, a membrane found at the surface of all bones, and forms the coccygeal ligament. There it is called the central ligament and assists with movements of the trunk of the body.[9]

Function

In conjunction with the other meningeal membranes, pia mater functions to cover and protect the central nervous system (CNS), to protect the blood vessels and enclose the venous sinuses near the CNS, to contain the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and to form partitions with the skull.[11] The CSF, pia mater, and other layers of the meninges work together as a protection device for the brain, with the CSF often referred to as the fourth layer of the meninges.

CSF production and circulation

Cerebrospinal fluid is circulated through the ventricles, cisterns, and subarachnoid space within the brain and spinal cord. About 150 mL of CSF is always in circulation, constantly being recycled through the daily production of nearly 500 mL of fluid. The CSF is primarily secreted by the choroid plexus; however, about one-third of the CSF is secreted by pia mater and the other ventricular ependymal surfaces (the thin epithelial membrane lining the brain and central canal) and arachnoidal membranes. The CSF travels from the ventricles and cerebellum through three foramina in the brain, emptying into the cerebrum, and ending its cycle in the venous blood via structures like the arachnoid granulations. The pia spans every surface crevice of the brain other than the foramina to allow the circulation of CSF to continue.[12]

Perivascular spaces

Pia mater allows for the formation of perivascular spaces that help serve as the brain’s lymphatic system. Blood vessels that penetrate the brain first pass across the surface and then go inwards toward the brain. This direction of flow leads to a layer of the pia mater being carried inwards and loosely adhering to the vessels, leading to the production of a space, namely a perivascular space, between the pia mater and each blood vessel. This is critical because the brain lacks a true lymphatic system. In the remainder of the body, small amounts of protein are able to leak from the parenchymal capillaries through the lymphatic system. In the brain, this ends up in the interstitial space. The protein portions are able to leave through the very permeable pia mater and enter the subarachnoid space in order to flow in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), eventually ending up in the cerebral veins. The pia mater serves to create these perivascular spaces to allow passage of certain material, such as fluids, proteins, and even extraneous particulate matter such as dead white blood cells from the blood stream to the CSF, and essentially the brain.[12]

Permeability

Due to the pia mater’s and the ependyma's high permeability, water and small molecules in the CSF are able to enter the brain interstitial fluid, so the interstitial brain fluid and the CSF are very similar in terms of composition.[3] However, regulation of this permeability is achieved through the abundant amount of astrocyte foot processes which are responsible for connecting the capillaries and the pia mater in a way that helps limit the amount of free diffusion going into the CNS.[13]

The function of the pia mater is more simply visualized through these ordinary occurrences. This last property is evident in cases of head injury. When the head comes into contact with another object, the brain is protected from the skull due to the similarity in density between these two fluids so that the brain does not simply smash through into the skull, but rather its movement is slowed and stopped by the viscous ability of this fluid. The contrast in permeability between the pia mater and the blood–brain barrier means that many drugs that enter the blood stream cannot enter the brain, but instead must be administered into the cerebrospinal fluid.[12]

Spinal cord compression

The pia mater also functions to deal with the deformation of the spinal cord under compression. Due to the high elastic modulus of the pia mater, it is able to provide a constraint on the surface of the spinal cord. This constraint stops the elongation of the spinal cord, as well as providing a high strain energy. This high strain energy is useful and responsible for the restoration of the spinal cord to its original shape following a period of decompression.[14]

Sensory

Ventral root afferents are unmyelinated sensory axons located within the pia mater. These ventral root afferents relay sensory information from the pia mater and allow for the transmission of pain from disc herniation and other spinal injury.[15]

Evolution

The significant increase in the size of the cerebral hemisphere through evolution has been made possible in part through the evolution of the vascular pia mater, which allows nutrient blood vessels to penetrate deep into the intertwined cerebral matter, providing the necessary nutrients in this larger neural mass. Throughout the course of life on earth, the nervous system of animals has continued to evolve to a more compact and increased organization of neurons and other nervous system cells. This process is most evident in vertebrates and especially mammals in which the increased size of the brain is generally condensed into a smaller space through the presence of sulci or fissures on the surface of the hemisphere divided into gyri allowing more superficies of the cortical grey matter to exist. The development of the meninges and the existence of a defined pia mater was first noted in the vertebrates, and has been more and more significant membrane in the brains of mammals with larger brains.[16]

Pathology

Meningitis is the inflammation of the pia and arachnoid mater. This is often due to bacteria that have entered the subarachnoid space, but can also be caused by viruses, fungi, as well as non-infectious causes such as certain drugs. It is believed that bacterial meningitis is caused by bacteria that enter the central nervous system through the blood stream. The molecular tools these pathogens would require to cross the meningeal layers and the blood–brain barrier are not yet well understood. Inside the subarachnoid, bacteria replicate and cause inflammation from released toxins such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) . These toxins have been found to damage the mitochondria and produce a large scale immune response. Headache and meningismus are often signs of inflammation relayed via trigeminal sensory nerve fibers within the pia mater. Disabling neuropsychological effects are seen in up to half of bacterial meningitis survivors. Research into how bacteria invade and enter the meningeal layers is the next step in prevention of the progression of meningitis.[17]

A tumor growing from the meninges is referred to as a meningioma. Most meningiomas grow from the arachnoid mater inward applying pressure on the pia mater and therefore the brain or spinal cord. While meningiomas make up 20% of primary brain tumors and 12% of spinal cord tumors, 90% of these tumors are benign. Meningiomas tend to grow slowly and therefore symptoms may arise years after initial tumor formation. The symptoms often include headaches and seizures due to the force the tumor creates on sensory receptors. The treatments available for these tumors include surgery and radiation.[18]

Additional images

Meninges of the CNS

Meninges of the CNS- Human brain dissection. Demonstrating removal of pia mater from the left cerebral hemisphere.

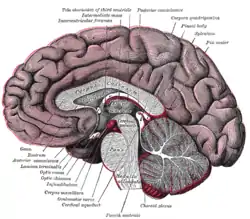

Median sagittal section of brain

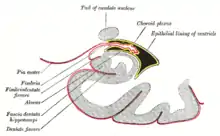

Median sagittal section of brain Coronal section of inferior horn of lateral ventricle

Coronal section of inferior horn of lateral ventricle Diagrammatic representation of a section across the top of the skull, showing the membranes of the brain, etc.

Diagrammatic representation of a section across the top of the skull, showing the membranes of the brain, etc. Diagrammatic section of scalp

Diagrammatic section of scalp Ultrastructural diagram of the cerebral cortex (Viorel Pais, 2012)

Ultrastructural diagram of the cerebral cortex (Viorel Pais, 2012)

Notes

- Entry "pia mater" in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, retrieved 2012-07-28.

- Levin, Emanuel; Sisson, Warden B. (8 June 1972). "The penetration of radiolabeled substances into rabbit brain from subarachnoid space". Brain Research. 41 (1): 145–153. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(72)90622-1. ISSN 0006-8993. PMID 5036032.

- Hladky, Stephen B.; Barrand, Margery A. (2 December 2014). "Mechanisms of fluid movement into, through and out of the brain: evaluation of the evidence". Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 11 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/2045-8118-11-26. ISSN 2045-8118. PMC 4326185. PMID 25678956.

- Jessen, Nadia Aalling; Munk, Anne Sofie Finmann; Lundgaard, Iben; Nedergaard, Maiken (1 December 2015). "The Glymphatic System: A Beginner's Guide". Neurochemical Research. 40 (12): 2583–2599. doi:10.1007/s11064-015-1581-6. ISSN 1573-6903. PMC 4636982. PMID 25947369.

- Parsons, Thomas. "Meninges". McGraw-Hill Companies 2008. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- "meninges". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Timmons, Martini (2006). Human Anatomy. San Francisco: Pearson/Benjamin Cummings.

- Polzin, Scott. "Meninges". Gale Encyclopedia of Neurological Disorders. 2005. Encyclopedia.com. 20 February 2011 <http://www.encyclopedia.com>. l

- Gray, Henry (1918). Susan Standring (ed.). Anatomy of the Human Body (40 ed.). Lea and Febiger.

- Saladin, Kenneth. Anatomy and Physiology- the Unity of Form and Function. 5th Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2010. 485. Print.

- Marieb, Elaine (2001). Human Anatomy & Physiology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. pp. 453, 455.

- Guyton, Arthur (2011). Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier.

- Berne, Robert (2008). Berne & Levy Physiology. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier.

- Ozawa, Hiroshi (July 2004). "Mechanical properties and function of the spinal pia mater". Journal of Neurosurgery. 1 (1): 122–127. doi:10.3171/spi.2004.1.1.0122. PMID 15291032.

- Remahl, Sten; Angeria (25 October 2010). "Observations at the CNS–PNS Border of Ventral Roots Connected to a Neuroma". Frontiers in Neurology. 1 (136): 136. doi:10.3389/fneur.2010.00136. PMC 3008941. PMID 21188264.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, additional text.

- Hoffman, Olaf; Weber (November 2009). "Pathophysiology and Treatment of Bacterial Meningitis". Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders. 2 (6): 401–412. doi:10.1177/1756285609337975. PMC 3002609. PMID 21180625.

- Tew, John. "Meningiomas". Mayfield Clinic. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

Further reading

- Martini, F. Timmons, M. and Tallitsch, R. Human Anatomy. 5th ed. San Francisco: Pearson/Benjamin Cummings, 2006.

- Saladin, Kenneth. Anatomy and Physiology- the Unity of Form and Function. 5th Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2010. 485. Print.

- Gray, Henry (1918). Susan Standring. ed. Anatomy of the Human Body (40 ed.). Lea and Febiger.

- Ozawa, Hiroshi (2004). "Mechanical properties and function of the spinal pia mater". Journal of Neurosurgery. 1 (1): 122–127. doi:10.3171/spi.2004.1.1.0122. PMID 15291032.

- Tubbs R, Salter G, Grabb P, Oakes W (2001). "The denticulate ligament: anatomy and functional significance". J Neurosurg. 94 (2 Suppl): 271–5. doi:10.3171/spi.2001.94.2.0271. PMID 11302630.

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Moore, Keith and Arthur F. Dalley. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2006.

- Pais V, Danaila L, Pais E (2012). "From pluripotent stem cells to multifunctional cordocytic phenotypes in the human brain: An ultrastructural study". Ultrastruct Pathol. 36 (4): 252–9. doi:10.3109/01913123.2012.669451. PMID 22849527. S2CID 19486572.

- Pais V, Danaila L, Pais E (2013). "Cordocytes-stem cells cooperation in the human brain with emphasis on pivotal role of cordocytes in perivascular areas of broken and thrombosed vessels". Ultrastruct Pathol. 37 (6): 425–32. doi:10.3109/01913123.2013.846449. PMID 24205927. S2CID 432311.

- Pais V, Danaila L, Pais E (2014). "The vascular stem cell niches and their significance in the brain". J Neurosurg Sci. 58 (3): 161–8. PMID 25033975.