Picoeukaryote

Picoeukaryotes are picoplanktonic eukaryotic organisms 3.0 µm or less in size. They are distributed throughout the world's marine and freshwater ecosystems and constitute a significant contribution to autotrophic communities. Though the SI prefix pico- might imply an organism smaller than atomic size, the term was likely used to avoid confusion with existing size classifications of plankton.

Characteristics

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

|

Cell structure

Picoeukaryotes can be either autotrophic and heterotrophic, and usually contain a minimal number of organelles. For example, Ostreococcus tauri, an autotrophic picoeukaryote belonging to the class Prasinophyceae, contains only the nucleus, one mitochondrion and one chloroplast, tightly packed within a cell membrane. Members of a heterotrophic class, the Bicosoecida, similarly contain only two mitochondria, one food vacuole and a nucleus.[1]

Distributions

These organisms are found throughout the water columns. Autotrophic picoeukaryotes are restricted to the upper 100–200 m (the layer that receives light) and are often characterized by a sharp cell maximum near the Deep Chlorophyll Maximum Layer (DCML)[2] and decrease significantly below.[3] Heterotrophic groups are found at greater depths and for example, in the Pacific Ocean, they have been found in the vicinity of hydrothermal vents at depths up to 2000–2550 m. Some heterotrophic lineages are found, unstratified, at all depths from the surface down to 3000 m.[1] They show high phylogenetic diversity[4][5] and high variability in global cell concentrations, ranging from 107 to 105 liter−1.[3]

Diversity

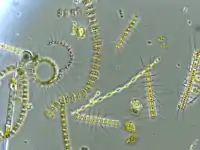

Autotrophic picoeukaryotes commonly found in nature are members of groups such as the Prasinophyceae[6] (a kind of green algae) and the Haptophyceae.[4][7] Despite their small size, these organisms have been found to contribute >10% of the total global aquatic net primary productivity.[8] Although much less abundant than cyanobacterial Photosynthetic picoplankton they have been shown to be as important in terms of biomass and primary production than picocyanobacteria.[9] In more oligotrophic environments, such as Station ALOHA, researchers believe that approximately 80% of the chlorophyll α biomass is due to cells in the pico-size range.[2] and picoeukaryotes are now known to make up a large fraction of the biomass and productivity in this size fraction in open ocean environments[10] and even in exported carbon in the North Atlantic Bloom.[11] Analysis of rDNA sequences indicate that heterotrophic oceanic picoeukaryotes belong to lineages such as the Alveolata, stramenopiles, choanoflagellates, and Acantharea.[5] In these lineages, many groups do not have cultured representatives yet. Grazing experiments have demonstrated that novel stramenopile picoeukaryotes are bacterivorous.[4]

Ecology

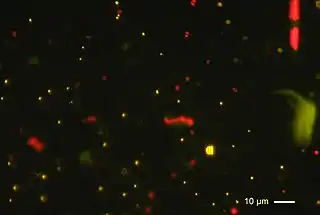

Since the size of these organisms determines how they interact with their environment, it is no surprise that they are not known to form significant sinking organic aggregates.[12] Their contribution to carbon cycling is difficult to assess because they are difficult to separate by techniques such as filtration.[13] Recent fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) experiments have shown that picoeukaryotes are fairly abundant in the deep sea.[1] Increased resolution with the development of better FISH techniques indicates that study and detection should become easier.[14] Additionally, qPCR has been a valuable approach for delineating and quantifying the different species, e.g. oceanic and coastal Bathycoccus[15] and Ostreococcus species.[16] Research has also shown that picoeukaryotes have a strong correlation with chlorophyll concentrations in both meso-autotrophic reservoirs and hypereutrophic reservoirs.[17] Moreover, nitrogen enrichment experiments suggest that picoeukaryotes have an advantage over larger cells when it comes to acquiring nutrients because of their large surface area per unit volume. They have exhibited more effectiveness in the uptake of photons and nutrient from low-resource environments.[8]

Biological characteristics

Photosynthetic picoeukaryotes, much like other planktonic species in the ocean photic zone, are exposed to light variations during the diel cycle and due to vertical displacement in the mixed layer of the water column. They have specialized biological reactions to help them deal with excessive densities of light, such as the Xanthophyll cycle.[18] However, there are also many types of non-photosynthetic picoeukaryotes that extend into the deep ocean and do not have these biochemical pathways.[19]

See also

- Bacterioplankton

- List of eukaryotic picoplankton species

- Phytoplankton

Notes

- Moreira, D.; P. Lopez-Garcia (2002). "The molecular ecology of microbial eukaryotes unveils a hidden world". Trends in Microbiology. 10 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02257-0. PMID 11755083.

- Campbell, Lisa and Daniel Vaulot. Photosynthetic picoplankton community structure in the subtropical north pacific ocean near Hawaii (station ALOHA). Archived 2011-05-20 at the Wayback Machine Deep-Sea Research Part I, Vol. 40, No. 10, pp. 2043-2060 (1993). Accessed April 30, 2008.

- Hall, J.A. and W.F. Vincent. Vertical and horizontal structure in the picoplankton communities of a coastal upwelling system. Marine Biology 106, 465-471 (1990). Accessed April 30, 2008.

- Massana, R. et al. Unveiling the Organisms behind Novel Eukaryotic Ribosomal DNA Sequences from the Ocean. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 4554-4558 (2002). Accessed April 30, 2008

- Moon-van der Staay, S. et al. Oceanic 18S rDNA sequences from picoplankton reveal unsuspected eukaryotic diversity. Nature 409, 607-610 (2001). Accessed April 30, 2008.

- Worden AZ (2006). "Picoeukaryote diversity in coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean". Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 43 (2): 165–175. doi:10.3354/ame043165.

- Cuvelier ML, et al. (2010). "Targeted metagenomics and ecology of globally important uncultured eukaryotic phytoplankton". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (33): 14679–84. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10714679C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1001665107. PMC 2930470. PMID 20668244.

- Fouilland, E. et al. Productivity and growth of a natural population of the smallest free-living eukaryote under nitrogen deficiency and sufficiency. Microbial Ecology 48, 103–110(2004). Accessed April 30, 2008.

- Worden AZ, Nolan JK, Palenik B (2004). "Assessing the dynamics and ecology of marine picophytoplankton: The importance of the eukaryotic component". Limnology and Oceanography. 49 (1): 168–179. Bibcode:2004LimOc..49..168W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.527.5206. doi:10.4319/lo.2004.49.1.0168. S2CID 86571162.

- Cuvelier ML, et al. (2010). "Targeted metagenomics and ecology of globally important uncultured eukaryotic phytoplankton". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (33): 14679–84. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10714679C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1001665107. PMC 2930470. PMID 20668244.

- Omand, M. M.; d'Asaro, E. A.; Lee, C. M.; Perry, M. J.; Briggs, N.; Cetini, I.; Mahadevan, A. (2015). "Eddy-driven subduction exports particulate organic carbon from the spring bloom". Science. 348 (6231): 222–225. Bibcode:2015Sci...348..222O. doi:10.1126/science.1260062. PMID 25814062.

- Waite, Anya M.; Safi, Karl A.; Hall, Julie A.; Nodder, Scott D. (2000). "Mass Sedimentation of Picoplankton Embedded in Organic Aggregates". Limnology and Oceanography. 45 (1): 87–97. Bibcode:2000LimOc..45...87W. doi:10.4319/lo.2000.45.1.0087. JSTOR 2670791.

- Worden, A. Z. et al. (2004). Assessing the dynamics and ecology of marine picophytoplankton: The importance of the eukaryotic component. Limnology and Oceanography 49: 168-79.

- Biegala, I.C. et al. Quantitative Assessment of Picoeukaryotes in the Natural Environment by Using Taxon-Specific Oligonucleotide Probes in Association with Tyramide Signal Amplification-Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization and Flow Cytometry. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 5519-5529 (2003). Accessed April 30, 2008.

- Limardo, Alexander J.; Sudek, Sebastian; Choi, Chang Jae; Poirier, Camille; Rii, Yoshimi M.; Blum, Marguerite; Roth, Robyn; Goodenough, Ursula; Church, Matthew J.; Worden, Alexandra Z. (2017). "Quantitative biogeography of picoprasinophytes establishes ecotype distributions and significant contributions to marine phytoplankton". Environmental Microbiology. 19 (8): 3219–3234. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13812. PMID 28585420.

- Demir-Hilton, Elif; Sudek, Sebastian; Cuvelier, Marie L.; Gentemann, Chelle L.; Zehr, Jonathan P.; Worden, Alexandra Z. (2011). "Global distribution patterns of distinct clades of the photosynthetic picoeukaryote Ostreococcus". The ISME Journal. 5 (7): 1095–1107. doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.209. PMC 3146286. PMID 21289652.

- Wang, Baoli et al. The distributions of autumn picoplankton in relation to environmental factors in the reservoirs along the Wujiang River in Guizhou Province, SW China. Hydrobiologia 598:35–45 (2008). Accessed April 30, 2008.

- Dimier, Celine. et al. Photophysiological properties of the marine picoeukaryote Picochlorum RCC 237 (Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta). J. Phycol. 43, 275–283 (2007). Accessed April 30, 2008.

- Not, Fabrice; Gausling, Rudolf; Azam, Farooq; Heidelberg, John F.; Worden, Alexandra Z. (2007). "Vertical distribution of picoeukaryotic diversity in the Sargasso Sea". Environmental Microbiology. 9 (5): 1233–1252. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01247.x. PMID 17472637.

External links

- MicrobeWiki A site on a biology Wiki run by Kenyon College