Mass deworming

Mass deworming, also called preventive chemotherapy,[1][2] is the process of treating large numbers of people, particularly children, for helminthiasis (for example soil-transmitted helminths (STH)) and schistosomiasis in areas with a high prevalence of these conditions.[3][4] It involves treating everyone – often all children who attend schools, using existing infrastructure to save money – rather than testing first and then only treating selectively. Serious side effects have not been reported when administering the medication to those without worms,[1][2] and testing for the infection is many times more expensive than treating it. Therefore, for the same amount of money, mass deworming can treat more people more cost-effectively than selective deworming.[5] Mass deworming is one example of mass drug administration.[3]

| Mass deworming | |

|---|---|

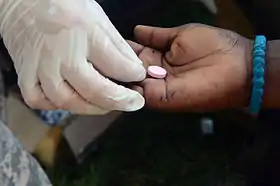

Nurse giving a deworming tablet to a child in Kakute, Uganda |

Mass deworming of children can be carried out by administering mebendazole and albendazole which are two types of anthelmintic drug.[5] The cost of providing one tablet every six to twelve months per child (typical doses) is relatively low.[6]

Soil-transmitted helminthiasis is the most prevalent neglected tropical disease.[7] Over 870 million children are at risk of parasitic worm infection.[8] Worm infections interfere with nutrient uptake, can lead to anemia, malnourishment and impaired mental and physical development, and pose a serious threat to children’s health, education, and productivity. Infected children are often too sick or tired to concentrate at school, or to attend at all.[9] In 2001, the World Health Assembly set a target for the World Health Organization (WHO) to treat 75% of school-aged children by 2010.[5]

Some non-governmental organizations support mass deworming, such as the Deworm the World Initiative (a project of the non-governmental organization Evidence Action), the END Fund (founded by Legatum Foundation in 2012),[10] the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, and Sightsavers. Because of the low cost of deworming children, large-scale implementation may provide wider benefits to society.[11]

Background

_gives_deworming_medication_to_a_child_at_the_Center_of_the_Grace_of_Good_Samaritan_Orp.jpg.webp)

_(3172335620).jpg.webp)

Intestinal parasitic worms (most of them falling in the category of soil-transmitted helminths) affect approximately 1.5 billion people, according to WHO estimates,[12] with 218 million needing preventive treatment for schistosoma-type worms in 2015.[13]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends mass deworming of children who live in endemic areas, in order to reduce morbidity by reducing the overall worm burden.[14] The WHO advises that worm infections adversely affect nutritional status, impair cognitive processes, and can cause conditions such as intestinal obstruction or lesions in the urinary tract and liver. Periodic drug treatment is expected to bring about health benefits such as reduced micronutrient loss, reduced environmental contamination, improved nutritional status and cognitive function, and better school performance in certain circumstances.[3][5]

In 2001, the World Health Assembly set a target for the WHO to treat 75 percent of school-aged children by 2010.[5] In 2014, over 396 million preschool and school-aged children were treated, corresponding to 47 percent of children at risk.[15]

Methods

Pills

Deworming programmes for children usually administer an anthelmintic drug such as albendazole or mebendazole (or praziquantel in a weight based or height based dose for schistosomiasis). The treatment is given as a single dose in a pill formulation.[3][5] Other drugs used, though not approved by the WHO, include pyrantel pamoate, piperazine, piperazine citrate, tetrachloroethylene, and levamisole.[3] In mass deworming programs, all children are given the medication, whether they are infected or not. In endemic areas, the deworming needs to be repeated regularly.[3] The frequency of the treatment depends on the prevalence and severity of infection which is determined by periodic surveys but is usually required annually.[5]

Accompanying measures

To increase the benefits of mass deworming and to lower the rate of reinfection, accompanying measures of mass deworming programmes should include water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions.[16] A good example for such a combined intervention is the Essential Health Care Program implemented by the Department of Education in the Philippines: This national programme combines twice annual deworming of school children with group handwashing with soap at set times of the day at the school premises.[17][18] This so-called "Fit for School" approach has also been implemented in Indonesia in 2014.[17]

Health aspects

Evidence

- In 2015, a review in a World Bank journal concluded that evidence supports a benefit with respect to school attendance and long term income.[19]

- A Cochrane review updated in 2019 found that high-quality medical evidence on mass deworming of children did not support beneficial effect on school performance, body weight, cognition, and rates of anemia.[3] However, it excluded a number of studies which showed positive long-term results as they did not meet the inclusion criteria of a pure control (for studies using the method of randomized controlled trials (RCT)). Supporters of mass deworming argue that these studies make a case for long-term benefits.[20][21]

- A review in 2016 examining the effects of deworming on child weight included studies omitted from Cochrane. It also extracted additional data from included studies. This review concluded that in environments with greater than 20% prevalence, where the WHO recommends mass treatment, the estimated average weight gain per dollar expenditure from deworming MDA is more than 35 times that estimated from school feeding programs.[22]

- In 2017, a systematic review and meta-analysis re-examined available studies and concluded that mass deworming for soil-transmitted helminths had little effect. However, for schistosomiasis, mass deworming might have been effective for weight but probably was ineffective for height, cognition, and school attendance.[23]

- A 2019 meta-analysis from the Campbell Collaboration found that mass deworming of pregnant women reduced maternal anemia by 23%, but there was no evidence of other effects.[24]

Reinfection and resistance

Reinfection with worms may begin shortly after the pill has killed the intestinal worm population.[25] Regular re-treatment together with an increased focus on other aspects of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) reduces the rates of infection in areas where parasitic worms are endemic.[16][25]

Resistance of worms to anthelmintic drugs over time is a possibility.[26]

Costs

Mass deworming has been determined to be cheap when calculated on a 'per child/per year'[6] or $/DALY[27] basis. Screening test to detect if a child is actually infected would be up to 12 times more expensive.[19]

The cost of treating a child for infection of soil transmitted helminths and schistosomes costs different amounts in different countries when administered as part of mass school-based deworming, but Evidence Action states that their recent programmes cost $0.56 or less per child per dose.[6] This programme is recommended by Giving What We Can and the Copenhagen Consensus Centre as one of the most efficient and cost-effective solutions. Modelling studies also suggest that deworming programmes are highly cost effective.[28]

National deworming programmes

National deworming programmes target children of school age, which the WHO defines as being between 5 and 14 years of age.[5] By 2015, the total global number estimated to be in deworming programmes was 495 million[29] and national deworming programs had been started in a number of countries. The world's largest deworming programme was started in 2015 in India, with an aim to target 240 million children at risk for parasitic worms.[30]

National deworming programmes listed by country in alphabetical order:

- Burundi: around 2 million children received two doses of medication in 2014.[31]

- Cameroon: began a deworming programme in 2006, it expanded to target 4 million children.[32]

- Côte d'Ivoire: more than 1.4 million children treated in 2014[31]

- Central African Republic: began a deworming programme in 2015 aiming to target 250,000 children.[33]

- Democratic Republic of Congo: began a deworming campaign in 2009 aiming to target 12.5 million children.[34]

- Ethiopia: announced it would begin a national deworming programme in 2015.[35] following an estimated 6.8 million children treated in 2014.[31]

- Gambia: began a deworming programme in 2010, by 2013 it was targeting 1.6 million children.[36]

- Kenya: began a deworming programme in 2009 of all children in 45 districts of high density STH infections.[37] By 2014, the programme had expanded to target 6 million children.[38]

- India: announced a deworming programme in 2015 which aimed to treat 240 million children.[30]

- Liberia: more than 600,000 children treated in 2014, but delayed due to ebola[31]

- Madagascar: began a deworming programme in 2012 aiming to target all of the children in the country, more than 5 million in total.[39]

- Malawi: around 2 million children targeted in a deworming programme in 2011.[40]

- Mozambique: began a deworming programme in 2007 when nearly 500,000 children were treated, by 2014 around 5 million were targeted.[41]

- Niger: began a deworming programme in 2004,[42] in 2014 more than 1.3 million children.[31]

- Senegal: more than 500,000 children treated in 2013.[31]

- Sierra Leone: 1.1 million school children received two doses of medication in 2011[43]

- Tanzania: more than 960,000 children treated in 2014.[31]

- Uganda: more than 500,000 received a biannual treatment in 2014.[31]

- Yemen: more than 2.5 million children treated in 2014, but programme on hold in 2015 due to political unrest.[31]

- Zambia: more than 90,000 children treated in 2014.[31]

- Zanzibar: almost 1.7 million children treated in 2014.[31]

Acceptance

Deworming programmes are widely accepted, although there have been some reports of parents refusing to allow their children to receive medication due to fears of illness, such as those reported in the media in the Philippines.[44] One survey in the Philippines reported that some parents will not allow their children to receive deworming tablets, while the majority would.[45] Another in rural China found that scepticism and local myths about the deworming programme could affect the uptake of medication.[46]

Other actors

UN agencies and NGOs

The UN is involved in mass deworming programmes via the World Food Programme,[47] UNICEF[37] and World Health Organization.[37]

NGOs involved in deworming advocacy or delivery include: the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, the Deworm the World Initiative from Evidence Action, Goods For Good, Save the Children, Counterpart International, Helen Keller International, the Carter Center, Inmed Partnerships for Children, Operation Blessing International, and Children Without Worms.[47]

Pharmaceutical companies

Biotechnology companies in the developing world have targeted neglected tropical diseases – which many helminth infections are classified as – and mass drug administration due to a need to improve global health.[48][49]

For example, in 2012 Johnson & Johnson pledged 200 million deworming tablets per year.[50]

Examples

Nicaragua

The national deworming programme was established as a partnership between the Pan American Health Organization – which serves as the Regional Office of the WHO, the Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases, the Inter-American Development Bank, Nicaraguan Government ministries, International NGOs and the main donor Children Without Worms.[51]

Children Without Worms is a public-private partnership between The Task Force for Global Health and Johnson & Johnson, who donated the mebendazole medication.[51] Intestinal helminths are a major problem in Nicaragua with 73% of rural households lacking clean drinking water and 73% lacking sanitation.[51]

Since 2009, drug donations from Johnson & Johnson have enabled annual deworming of school-aged children and medication supplied by other NGOs has enabled deworming of pre-school children, although questions were raised as to whether the frequency should have been increased.[51]

Burundi

In 2007, Burundi undertook a parasitological survey across its population which demonstrated that intestinal schistosomiasis was highly focalised in areas close to water and soil-transmitted helminthiases, including hook worm, was more widely distributed amongst its people. The report demonstrated the suitability of a mass drug administration for the entire population.[52] The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative had developed an approach which would cost 50 US cents per person per year, and was piloted in Burundi and Rwanda in 2007 with a $9 million investment from the Legatum Foundation, along with support from various other government donors, philanthropists and pharmaceutical companies, over a four-year period.[10][53][52]

Soil Transmitted Helminth Control Program run by the Department of Health

The Philippines Soil Transmitted Helminth Control Program is run by the Department of Health and implemented by the Department of Education in the Philippines.[54] It is a partnership with the WHO, University of the Philippines Manila, UNICEF, World Vision International, Feed the Children, Helen Keller International, Plan International and Save the Children.[54] It involves giving all children doses of Albendazole or Mebendazole.[54]

However, in 2013 the Director of the National Institute of Health in the Philippines questioned the effectiveness of the programme because it only covered only 20% of affected children with an infection rate of 44%.[55] By 2015, 16 million children were targeted in the deworming programme.[56] with some media claims that some of the medication was found to be expired.[57] Government officials later denied this.[58] Other national press reports in July 2015 stated that a small number of children had been admitted to hospital due to an "adverse effect" of the deworming medication.[44]

Essential Health Care Program implemented by the Philippine Department of Education

Successful deworming and positive health outcomes were also achieved by the Essential Health Care Program implemented by the Department of Education in the Philippines. This national programme includes giving school children deworming drugs twice a year, as well as group handwashing with soap and brushing teeth daily with fluoride toothpaste as a group activity at set times of the day at the school premises.[17] In 2012 UNICEF described it as an "outstanding example of at scale action to promote children’s health and education".[18]

United States

Public health campaigns to reduce helminth infections in the U.S. may be traced as far back as 1910, when the Rockefeller Foundation began the fight against hookworm – the so-called "germ of laziness" – which was found to infect 40% of children in the American South.[59][60] Records of the programme suggest that it led to increased school enrollment and attendance for children, and improved literacy and income for adults who were treated as children.[59][61] This campaign was enthusiastically received by educators throughout the region; as one Virginian school observed: "children who were listless and dull are now active and alert; children who could not study a year ago are not only studying now, but are finding joy in learning... for the first time in their lives their cheeks show the glow of health."[61] From Louisiana, a grateful school board added: "As a result of your treatment ... their lessons are not so hard for them, they pay better attention in class and they have more energy ... In short, we have here in our school-rooms today about 120 bright, rosy-faced children, whereas had you not been sent here to treat them we would have had that many pale-faced, stupid children."[61]

Military personnel returning from the Second World War were found to be bringing intestinal worms back to the United States, so in 1947 the American Society of Parasitologists called for increased attention on deworming.[59]

History

Following World War II, the World Health Organization "has been the principal body concerned with the international support of research and control programmes" of schistosomiasis.[62]: 266

In 2001, the World Health Assembly declared the goal of 75% of schoolchildren in endemic areas receiving deworming treatment.[63]: 2

References

- WHO (2006). Preventive chemotherapy in human helminthiasis: coordinated use of anthelminthic drugs in control interventions: a manual for health professionals and programme managers (PDF). WHO Press, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. pp. 1–61. ISBN 9241547103.

- Albonico M, Allen H, Chitsulo L, Engels D, Gabrielli AF, Savioli L (March 2008). "Controlling soil-transmitted helminthiasis in pre-school-age children through preventive chemotherapy". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (3): e126. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000126. PMC 2274864. PMID 18365031.

- Taylor-Robinson DC, Maayan N, Donegan S, Chaplin M, Garner P (September 2019). "Public health deworming programmes for soil-transmitted helminths in children living in endemic areas". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD000371. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000371.pub7. PMC 6737502. PMID 31508807.

- Gabrielli AF, Montresor A, Chitsulo L, Engels D, Savioli L (December 2011). "Preventive chemotherapy in human helminthiasis: theoretical and operational aspects". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 105 (12): 683–93. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.08.013. PMC 5576527. PMID 22040463.

- Helminth control in school-age children: a guide for managers of control programmes (PDF) (2nd ed.). World Health Organization. 2011. pp. vii. ISBN 9789241548267.

- Williams, Katherine (16 January 2015). "How do we calculate the cost of deworming?". Evidence Action. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Lo, Nathan C.; Heft-Neal, Sam; Coulibaly, Jean T.; Leonard, Leslie; Bendavid, Eran; Addiss, David G. (2019-11-01). "State of deworming coverage and equity in low-income and middle-income countries using household health surveys: a spatiotemporal cross-sectional study". The Lancet Global Health. 7 (11): e1511–e1520. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30413-9. ISSN 2214-109X. PMC 7024997. PMID 31558383.

- "Soil Transmitted Helminths". WHO. Archived from the original on August 20, 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Baird S, Hicks JH, Kremer M, Miguel E (November 2016). "Worms at Work: Long-run Impacts of a Child Health Investment" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 131 (4): 1637–1680. doi:10.1093/qje/qjw022. PMC 5094294. PMID 27818531.

- "Philanthropy: the search for the best way to give". Financial Times. April 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- "GiveWell Top Charities". Givewell. 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- "Soil-transmitted helminth infections". WHO. January 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- "Schistosomiasis fact sheet". WHO. January 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- "WHO intestinal worms strategy". who.int. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- "Soil-transmitted helminthiases: number of children treated in 2014" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. World Health Organization. 90 (51/52): 701–712. 18 December 2015. ISSN 0049-8114.

- Ziegelbauer K, Speich B, Mäusezahl D, Bos R, Keiser J, Utzinger J (January 2012). "Effect of sanitation on soil-transmitted helminth infection: systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 9 (1): e1001162. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001162. PMC 3265535. PMID 22291577.

- School Community Manual - Indonesia (formerly Manual for teachers), Fit for School. GIZ Fit for School, Philippines. 2014. ISBN 978-3-95645-250-5.

- UNICEF (2012) Raising Even More Clehran Hands: Advancing Health, Learning and Equity through WASH in Schools, Joint Call to Action

- Ahuja A, Baird S, Hicks JH, Kremer M, Miguel E, Powers S (2015). "When Should Governments Subsidize Health? The Case of Mass Deworming". The World Bank Economic Review. 29 (suppl 1): S9–S24. doi:10.1093/wber/lhv008.

- Ozier O (Oct 2014). "Exploiting Externalities to Estimate the Long-Term Effects of Early Childhood Deworming" (PDF). World Bank Group.

- "New deworming reanalyses and Cochrane review". The GiveWell Blog. July 24, 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Croke K, Hicks JH, Hsu E, Kremer M, Miguel E (July 2016). "Does Mass Deworming Affect Child Nutrition? Meta-analysis, Cost-Effectiveness, and Statistical Power". NBER Working Paper No. 22382. doi:10.3386/w22382.

- Welch VA, Ghogomu E, Hossain A, Awasthi S, Bhutta ZA, Cumberbatch C, et al. (January 2017). "Mass deworming to improve developmental health and wellbeing of children in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". The Lancet. Global Health. 5 (1): e40–e50. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30242-X. PMID 27955788.

- Salam RA, Cousens S, Welch V, Gaffey M, Middleton P, Makrides M, et al. (2019). "Mass deworming for soil-transmitted helminths and schistosomiasis among pregnant women: A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis". Campbell Systematic Reviews. 15 (3): e1052. doi:10.1002/cl2.1052. ISSN 1891-1803.

- Jia TW, Melville S, Utzinger J, King CH, Zhou XN (2012). "Soil-transmitted helminth reinfection after drug treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (5): e1621. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001621. PMC 3348161. PMID 22590656.

- Levecke B, Montresor A, Albonico M, Ame SM, Behnke JM, Bethony JM, et al. (October 2014). "Assessment of anthelmintic efficacy of mebendazole in school children in six countries where soil-transmitted helminths are endemic". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (10): e3204. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003204. PMC 4191962. PMID 25299391.

- "Cost-effectiveness in $/DALY for deworming interventions". Givewell.org. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Lo NC, Bogoch II, Blackburn BG, Raso G, N'Goran EK, Coulibaly JT, et al. (October 2015). "Comparison of community-wide, integrated mass drug administration strategies for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: a cost-effectiveness modelling study". The Lancet. Global Health. 3 (10): e629–38. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00047-9. PMID 26385302.

- "Deworming campaign improves child health, school attendance in Rwanda". WHO.int. 2015. Archived from the original on July 18, 2015.

- "World's largest deworming program in India to start". Evidence Action. 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "SCI Summary sheet of treatments instigated and overseen by SC". Givewell. 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- "Scaling Cameroon's deworming program to the national level". Children Without Worms. 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "The Central African Republic: going beyond providing food as part of our school meal programme". World Food Programme. 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "DRC: National deworming campaign under way". IRIN. 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Ethiopia launches school program to treat parasitic worms". Reuters. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Gambia SHN success story". Schools and Health. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Kabaka S, Kisia CW (2011). "National deworming program - Kenya's experience" (PDF). World Conference on the Social Determinants of Health.

- "Kenya national deworming programme". Children's Investment Fund Foundation. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Deworming in Madagascar: the power of partnerships". Children Without Worms. 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Child Health Week reaches more than two million children in Malawi". UNICEF Malawi. 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Schistosomasis control initiative - Mozambique". Imperial College. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Leslie J, Garba A, Oliva EB, Barkire A, Tinni AA, Djibo A, et al. (October 2011). "Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth control in Niger: cost effectiveness of school based and community distributed mass drug administration [corrected]". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 5 (10): e1326. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001326. PMC 3191121. PMID 22022622.

- "Sierra Leone". Helen Keller International. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Garcia B (July 2015). "Deworming tablet downs hundreds of schoolchildren". Sun Star. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Parikh DS, Totañes FI, Tuliao AH, Ciro RN, Macatangay BJ, Belizario VY (September 2013). "Knowledge, attitudes and practices among parents and teachers about soil-transmitted helminthiasis control programs for school children in Guimaras, Philippines" (PDF). The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 44 (5): 744–52. PMID 24437309.

- Lu L, Liu C, Zhang L, Medina A, Smith S, Rozelle S (March 2015). "Gut instincts: knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding soil-transmitted helminths in rural China". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (3): e0003643. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003643. PMC 4373855. PMID 25807188.

- Global NGO Deworming Inventory 2010 (2011). "2010 Global NGO Deworming Inventory summary report: deworming programs by country" (PDF). deworminginventory.org.

- Frew SE, Liu VY, Singer PA (2009). "A business plan to help the 'global South' in its fight against neglected diseases" (PDF). Health Affairs. 28 (6): 1760–73. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.1760. PMID 19887417.

- Keenan JD, Hotez PJ, Amza A, Stoller NE, Gaynor BD, Porco TC, Lietman TM (2013). "Elimination and eradication of neglected tropical diseases with mass drug administrations: a survey of experts". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 7 (12): e2562. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002562. PMC 3855072. PMID 24340111.

- Fenwick A (March 2012). "The global burden of neglected tropical diseases". Public Health. 126 (3): 233–236. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2011.11.015. PMID 22325616.

- Lucien F, Janus CB (2011). "Worms and WASH(ED) Nicaragua" (PDF). The George Washington University. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ndayishimiye O, Ortu G, Soares Magalhaes RJ, Clements A, Willems J, Whitton J, et al. (May 2014). "Control of neglected tropical diseases in Burundi: partnerships, achievements, challenges, and lessons learned after four years of programme implementation". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (5): e2684. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002684. PMC 4006741. PMID 24785993.

- "National Programme Managers and Partners Meet to Take Stock of Progress in the African Region". July 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- "Soil Transmitted Helminth Control Program". Republic of the Philippines Department of Health. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Tubeza P (2013). "Gov deworming programme in public schools not very effective". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Crisostomo S (July 2015). "DOH targets deworming of 16M students". philststar. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Geronimo J (2015). "DOH looks into 'expired' deworming medicine claim". Rappler. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Jocson L (2015). "DOH confirms deworming medicine not expired". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Bundy DA, Walson JL, Watkins KL (March 2013). "Worms, wisdom, and wealth: why deworming can make economic sense". Trends in Parasitology. 29 (3): 142–48. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2012.12.003. PMID 23332661.

- Watkins WE, Pollitt E (March 1997). ""Stupidity or worms": do intestinal worms impair mental performance?". Psychological Bulletin. 121 (2): 171–91. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.121.2.171. PMID 9100486.

- Bleakley H (2007). "Disease and Development: Evidence from Hookworm Eradication in the American South". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 122 (1): 73–117. doi:10.1162/qjec.121.1.73. PMC 3800113. PMID 24146438.

- Sandbach FR (July 1976). "The history of schistosomiasis research and policy for its control". Medical History. 20 (3): 259–75. doi:10.1017/s0025727300022663. PMC 1081781. PMID 792584.

- Donald A.P. Bundy, Judd L. Walson, and Kristie L. Watkins (2013). "Worms, wisdom, and wealth: why deworming can make economic sense" (PDF). Retrieved April 16, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)