Salicylate sensitivity

Salicylate sensitivity is any adverse effect that occurs when a usual amount of salicylate is ingested. People with salicylate intolerance are unable to consume a normal amount of salicylate without adverse effects.

| Salicylate sensitivity | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Salicylate intolerance |

| |

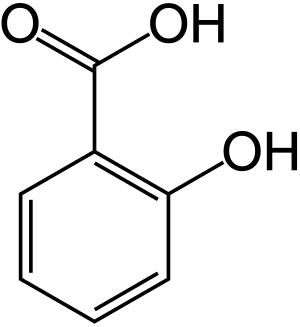

| Salicylic acid | |

Salicylate sensitivity differs from salicylism, which occurs when an individual takes an overdose of salicylates.[1] Salicylate overdose can occur in people without salicylate sensitivity, and can be deadly if untreated. For more information, see aspirin poisoning.

Salicylates are derivatives of salicylic acid that occur naturally in plants and serve as a natural immune hormone and preservative, protecting the plants against diseases, insects, fungi, and harmful bacteria. Salicylates can also be found in many medications, perfumes and preservatives. Both natural and synthetic salicylates can cause health problems in anyone when consumed in large doses. But for those who are salicylate intolerant, even small doses of salicylate can cause adverse reactions.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of salicylate sensitivity are:

- Stomach discomfort or diarrhea[2]

- Itchy skin, hives or rashes[2]

- Asthma and other breathing difficulties[2]

- Rhinitis, sinusitis, nasal polyps[2]

- Pseudoanaphylaxis[2]

- Angioedema

- Headaches

- Bed wetting or urgency to urinate

- Changes in skin color/skin discoloration

- Fatigue

- Sore, itchy, puffy or burning eyes

- Hyperactivity

- Memory loss and poor concentration

- Depression

- Tinnitus ringing of the ears

- Swelling of hands, feet, eyelids, face and/or lips

Asthma and nasal polyps are also symptoms of Aspirin Exacerbated Respiratory Disease (AERD, Samter's Triad), which is not believed to be caused by dietary salicylates.

Diagnosis

There is no laboratory test for salicylate sensitivity. Typically testing is done by an "elimination challenge," to see if symptoms improve, or "provocative challenge," which intends to induce a controlled reaction as a means of confirming diagnosis. During provocative challenge, the person is given incrementally higher doses of salicylates, usually aspirin, under medical supervision, until either symptoms appear or the likelihood of symptoms appearing is ruled out. This only pertains to short-term symptoms such as digestive, respiratory, and skin itching, rather than slower-developing symptoms such as nasal polyps.[2]

Treatment

Salicylate sensitivity can be treated with the use of low-salicylate diets, such as the Feingold Diet. The Feingold Diet removes artificial colors and preservatives and salicylates, whereas the Failsafe Diet removes salicylates, as well as amines and glutamates.[3] The range of foods that have no salicylate content is very limited, and consequently salicylate-free diets are very restricted.

Montelukast is one form of treatment used in aspirin-intolerant asthma.[4]

History

An important salicylate drug is aspirin, which has a long history. Aspirin intolerance was widely known by 1975, when the understanding began to emerge that it is a pharmacological reaction, not an allergy.[5][6]

Terminology

Salicylate intolerance is a form of food intolerance or of drug intolerance.

Salicylate sensitivity is a pharmacological reaction, not a true IgE-mediated allergy. However, it is possible for aspirin to trigger non-allergic hypersensitivity reactions.[7][8] About 5–10% of asthmatics have aspirin hypersensitivity, but dietary salicylates have been shown not to contribute to this. The reactions in AERD (Samter's triad) are due to inhibition of the COX-1 enzyme by aspirin, as well as other NSAIDs that are not salicylates. Dietary salicylates have not been shown to significantly affect COX-1.[9]

Samter's triad refers to NSAID sensitivity in conjunction with nasal polyps and asthma.[10]

References

- "salicylism" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Hanns-Wolf Baenkler (2008). "Salicylate Intolerance: Pathophysiology, Clinical Spectrum, Diagnosis and Treatment". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 105 (8): 137–142. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2008.0137. PMC 2696737. PMID 19633779.

- Matthews J. "Feingold Diet / Failsafe Diet". Nourishing Hope.

- Kim SH, Ye YM, Hur GY, Lee SK, Sampson AP, Lee HY, Park HS (September 2007). "CysLTR1 promoter polymorphism and requirement for leukotriene receptor antagonist in aspirin-intolerant asthma patients". Pharmacogenomics. 8 (9): 1143–50. doi:10.2217/14622416.8.9.1143. PMID 17924829.

- Casterline CL (November 1975). "Intolerance to aspirin". American Family Physician. 12 (5): 119–22. PMID 1199905.

- Patriarca G, Venuti A, Schiavino D, Fais G (1976). "Intolerance to aspirin: clinical and immunological studies". Zeitschrift für Immunitatsforschung. Immunobiology. 151 (4): 295–304. doi:10.1016/s0300-872x(76)80024-8. PMID 936715.

- Palikhe NS, Kim SH, Park HS (October 2008). "What do we know about the genetics of aspirin intolerance?". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 33 (5): 465–72. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00961.x. PMID 18834360. S2CID 22584486.

- Narayanankutty A, Reséndiz-Hernández JM, Falfán-Valencia R, Teran LM (May 2013). "Biochemical pathogenesis of aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD)". Review. Clinical Biochemistry. 46 (7–8): 566–78. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.12.005. PMID 23246457.

- Jang AS, Park JS, Park SW, Kim DJ, Uh ST, Seo KH, Kim YH, et al. (November 2008). "Obesity in aspirin-tolerant and aspirin-intolerant asthmatics". Respirology. 13 (7): 1034–8. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01358.x. PMID 18699807. S2CID 26399839.

- Kim JE, Kountakis SE (July 2007). "The prevalence of Samter's triad in patients undergoing functional endoscopic sinus surgery". Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal. 86 (7): 396–9. doi:10.1177/014556130708600715. PMID 17702319.

Further reading

- Parmet S, Lynm C, Glass RM (December 2004). "JAMA patient page. Aspirin sensitivity". JAMA. 292 (24): 3098. doi:10.1001/jama.292.24.3098. PMID 15613676.

External links

- "Salicylate Sensitivity Forums and Food/Product Guides". SalicylateSensitivity.com.