Poisoning

A poison can be any substance that is harmful to the body. It can be swallowed, inhaled, injected or absorbed through the skin. Poisoning is the harmful effect that occurs when too much of that substance has been taken.[2] Poisoning is not to be confused with envenomation.

| Poisoning | |

|---|---|

| |

| The symbol of a toxic substance | |

| Specialty | Toxicology |

Acute poisoning is exposure to a poison on one occasion or during a short period of time. Symptoms develop in close relation to the degree of exposure. Absorption of a poison is necessary for systemic poisoning (that is, in the blood throughout the body). In contrast, substances that destroy tissue but do not absorb, such as lye, are classified as corrosives rather than poisons. Furthermore, many common household medications are not labeled with skull and crossbones, although they can cause severe illness or even death. In the medical sense, toxicity and poisoning can be caused by less dangerous substances than those legally classified as a poison. Toxicology is the study and practice of the symptoms, mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment of poisoning.

Chronic poisoning is long-term repeated or continuous exposure to a poison where symptoms do not occur immediately or after each exposure. The patient gradually becomes ill, or becomes ill after a long latent period. Chronic poisoning most commonly occurs following exposure to poisons that bioaccumulate, or are biomagnified, such as mercury, gadolinium, and lead.

Contact or absorption of poisons can cause rapid death or impairment. Agents that act on the nervous system can paralyze in seconds or less, and include both biologically derived neurotoxins and so-called nerve gases, which may be synthesized for warfare or industry.

Inhaled or ingested cyanide, used as a method of execution in gas chambers, almost instantly starves the body of energy by inhibiting the enzymes in mitochondria that make ATP. Intravenous injection of an unnaturally high concentration of potassium chloride, such as in the execution of prisoners in parts of the United States, quickly stops the heart by eliminating the cell potential necessary for muscle contraction.

Most biocides, including pesticides, are created to act as poisons to target organisms, although acute or less observable chronic poisoning can also occur in non-target organisms (secondary poisoning), including the humans who apply the biocides and other beneficial organisms. For example, the herbicide 2,4-D imitates the action of a plant hormone, which makes its lethal toxicity specific to plants. Indeed, 2,4-D is not a poison, but classified as "harmful" (EU).

Many substances regarded as poisons are toxic only indirectly, by toxication. An example is "wood alcohol" or methanol, which is not poisonous itself, but is chemically converted to toxic formaldehyde and formic acid in the liver. Many drug molecules are made toxic in the liver, and the genetic variability of certain liver enzymes makes the toxicity of many compounds differ between people.

Exposure to radioactive substances can produce radiation poisoning, an unrelated phenomenon.

Treatment

If a person is suspected to have been exposed or ingested a poison, medical assistance to determine an appropriate treatment is necessary. If a suspected poisoning has occurred but the person is awake and alert, it is recommended to call the local poison information centre.[3] If the person has collapsed or is having difficulty breathing, emergency medical assistance is required.[3][4] To assist medical personnel, describe the person's symptoms, age, weight, other medications that person is taking, and any information about the poison. Try to determine the amount ingested and how long since the person was exposed to it. If possible, have on hand the pill bottle, medication package or other suspect container.[5]

The treatment will depend on the substance to which the patient is exposed. Depending on the type of poisoning, some first aid measures may help. Treatments include activated charcoal, induction of vomiting and dilution or neutralizing of the poison.[6]

Prevention

Prevention strategies include locking up medicines and cleaners, reading labels on medicines and cleaners before using or storing, and safely discarding unneeded medicines, herbal supplements, and vitamins.[3]

References

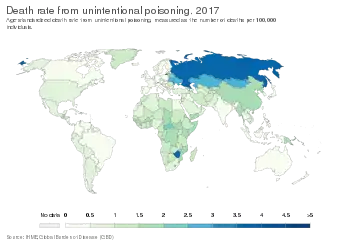

- "Death rate from unintentional poisoning". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Poisoning". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- "Poisoning Prevention | Child Safety and Injury Prevention| CDC Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 2020-07-02. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- Yadav, Sharad; Shah, Gautam Kumar; Verma, Dharmesh; Yadav, Prakash Chand (2022-07-22). "Study of profile, pattern and outcomes of oral poisoning cases admitted in emergency department of Janakpur provincial hospital, Nepal". doi:10.5281/zenodo.6879818.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Poisoning: First aid - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- Avau, Bert; Borra, Vere; Vanhove, Anne-Catherine; Vandekerckhove, Philippe; De Paepe, Peter; De Buck, Emmy (December 2018). "First aid interventions by laypeople for acute oral poisoning". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD013230. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013230. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6438817. PMID 30565220.