Serology

Serology is the scientific study of serum and other body fluids. In practice, the term usually refers to the diagnostic identification of antibodies in the serum.[1] Such antibodies are typically formed in response to an infection (against a given microorganism),[2] against other foreign proteins (in response, for example, to a mismatched blood transfusion), or to one's own proteins (in instances of autoimmune disease). In either case, the procedure is simple.

Serological tests

Serological tests are diagnostic methods that are used to identify antibodies and antigens in a patient's sample. Serological tests may be performed to diagnose infections and autoimmune illnesses, to check if a person has immunity to certain diseases, and in many other situations, such as determining an individual's blood type.[1] Serological tests may also be used in forensic serology to investigate crime scene evidence.[3] Several methods can be used to detect antibodies and antigens, including ELISA,[4] agglutination, precipitation, complement-fixation, and fluorescent antibodies and more recently chemiluminescence.[5]

Microbiology

In microbiology, serologic tests are used to determine if a person has antibodies against a specific pathogen, or to detect antigens associated with a pathogen in a person's sample.[6] Serologic tests are especially useful for organisms that are difficult to culture by routine laboratory methods, like Treponema pallidum (the causative agent of syphilis), or viruses.[7]

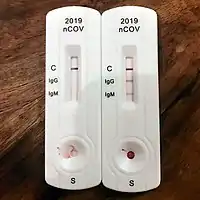

The presence of antibodies against a pathogen in a person's blood indicates that they have been exposed to that pathogen. Most serologic tests measure one of two types of antibodies: immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG). IgM is produced in high quantities shortly after a person is exposed to the pathogen, and production declines quickly thereafter. IgG is also produced on the first exposure, but not as quickly as IgM. On subsequent exposures, the antibodies produced are primarily IgG, and they remain in circulation for a prolonged period of time.[6]

This affects the interpretation of serology results: a positive result for IgM suggests that a person is currently or recently infected, while a positive result for IgG and negative result for IgM suggests that the person may have been infected or immunized in the past. Antibody testing for infectious diseases is often done in two phases: during the initial illness (acute phase) and after recovery (convalescent phase). The amount of antibody in each specimen (antibody titer) is compared, and a significantly higher amount of IgG in the convalescent specimen suggests infection as opposed to previous exposure.[8] False negative results for antibody testing can occur in people who are immunosuppressed, as they produce lower amounts of antibodies, and in people who receive antimicrobial drugs early in the course of the infection.[7]

Transfusion medicine

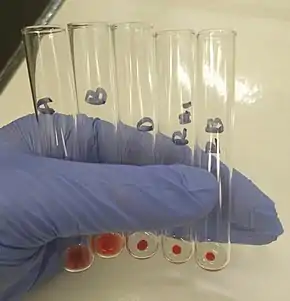

Blood typing is typically performed using serologic methods. The antigens on a person's red blood cells, which determine their blood type, are identified using reagents that contain antibodies, called antisera. When the antibodies bind to red blood cells that express the corresponding antigen, they cause red blood cells to clump together (agglutinate), which can be identified visually. The person's blood group antibodies can also be identified by adding plasma to cells that express the corresponding antigen and observing the agglutination reactions.[9][6]

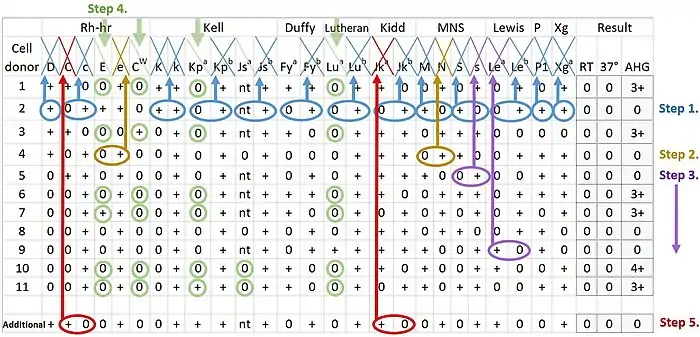

Other serologic methods used in transfusion medicine include crossmatching and the direct and indirect antiglobulin tests. Crossmatching is performed before a blood transfusion to ensure that the donor blood is compatible. It involves adding the recipient's plasma to the donor blood cells and observing for agglutination reactions.[9] The direct antiglobulin test is performed to detect if antibodies are bound to red blood cells inside the person's body, which is abnormal and can occur in conditions like autoimmune hemolytic anemia, hemolytic disease of the newborn and transfusion reactions.[10] The indirect antiglobulin test is used to screen for antibodies that could cause transfusion reactions and identify certain blood group antigens.[11]

Immunology

Serologic tests can help to diagnose autoimmune disorders by identifying abnormal antibodies directed against a person's own tissues (autoantibodies).[12] All people have different immunology graphs.

Serological surveys

A 2016 research paper by Metcalf et al., amongst whom were Neil Ferguson and Jeremy Farrar, stated that serological surveys are often used by epidemiologists to determine the prevalence of a disease in a population. Such surveys are sometimes performed by random, anonymous sampling from samples taken for other medical tests or to assess the prevalence of antibodies of a specific organism or protective titre of antibodies in a population. Serological surveys are usually used to quantify the proportion of people or animals in a population positive for a specific antibody or the titre or concentrations of an antibody. These surveys are potentially the most direct and informative technique available to infer the dynamics of a population's susceptibility and level of immunity. The authors proposed a World Serology Bank (or serum bank) and foresaw "associated major methodological developments in serological testing, study design, and quantitative analysis, which could drive a step change in our understanding and optimum control of infectious diseases."[13]

In a helpful reply entitled "Opportunities and challenges of a World Serum Bank", de Lusignan and Correa observed[14] that the

principal ethical and logistical challenges that need to be overcome are the methods of obtaining specimens, how informed consent is acquired in busy practices, and the filling in of gaps in patient sampling.

In another helpful reply on the World Serum Bank, the Australian researcher Karen Coates declared that:[15]

Improved serological surveillance would allow governments, aid agencies, and policy writers to direct public health resources to where they are needed most. A better understanding of infection dynamics with respect to the changing patterns of global weather should inform policy measures including where to concentrate vaccination efforts and insect control measures.

In April 2020, Justin Trudeau formed the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force, whose mandate is to carry out a serological survey in a scheme hatched in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.[16][17]

See also

- Medical laboratory

- Seroconversion

- Serovar

- Medical technologist

- Dr. Geoffrey Tovey, noted serologist

- Forensic serology

References

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 247–9. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- Washington JA (1996). "Principles of Diagnosis". In Baron S, et al. (eds.). Principles of Diagnosis: Serodiagnosis. in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2.

- Gardner, Ross M. (2011). Practical crime scene processing and investigation (Second ed.). CRC Press.

- "Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)". British Society for Immunology.

- Atmar, Robert L. (2014), "Immunological Detection and Characterization", Viral Infections of Humans, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 47–62, doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-7448-8_3, ISBN 978-1-4899-7447-1, S2CID 68212270, retrieved 2021-06-13

- Mary Louise Turgeon (10 February 2015). Linne & Ringsrud's Clinical Laboratory Science - E-Book: The Basics and Routine Techniques. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 586–95, 543, 556. ISBN 978-0-323-37061-5.

- Frank E. Berkowitz; Robert C. Jerris (15 February 2016). Practical Medical Microbiology for Clinicians. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1-119-06674-3.

- Connie R. Mahon; Donald C. Lehman; George Manuselis (18 January 2018). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 193–4. ISBN 978-0-323-48212-7.

- Denise M Harmening (30 November 2018). Modern Blood Banking & Transfusion Practices. F.A. Davis. pp. 65, 261. ISBN 978-0-8036-9462-0.

- American Association for Clinical Chemistry (24 December 2019). "Direct Antiglobulin Test". Lab Tests Online. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Richard A. McPherson; Matthew R. Pincus (6 September 2011). Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 714–5. ISBN 978-1-4557-2684-4.

- American Association for Clinical Chemistry (13 November 2019). "Autoantibodies". Lab Tests Online. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Metcalf, C Jessica E.; Farrar, Jeremy; Cutts, Felicity T.; Basta, Nicole E.; Graham, Andrea L.; Lessler, Justin; Ferguson, Neil M.; Burke, Donald S.; Grenfell, Bryan T. (2016). "Use of serological surveys to generate key insights into the changing global landscape of infectious disease". The Lancet. 388 (10045): 728–730. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30164-7. PMC 5678936. PMID 27059886.

- De Lusignan, Simon; Correa, Ana (2017). "Opportunities and challenges of a World Serum Bank". The Lancet. 389 (10066): 250–251. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30046-6. PMID 28118910.

- Coates, Karen M. (2017). "Opportunities and challenges of a World Serum Bank". The Lancet. 389 (10066): 251–252. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30052-1. PMID 28118912.

- "WHO set pandemic response back by 2-3 weeks, says doctor on new federal task force". CBC. 23 April 2020.

- "Prime Minister announces new support for COVID-19 medical research and vaccine development". Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada. 23 April 2020.

External links

- Serology (archived) – MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia

- Serologic+Tests at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)