Subcutaneous emphysema

Subcutaneous emphysema (SCE, SE) occurs when gas or air accumulates and seeps under the skin, where normally no gas should be present. Subcutaneous refers to the subcutaneous tissue, and emphysema refers to trapped air pockets resembling the pneumatosis seen in pulmonary emphysema. Since the air generally comes from the chest cavity, subcutaneous emphysema usually occurs around the upper torso, such as on the chest, neck, face, axillae and arms, where it is able to travel with little resistance along the loose connective tissue within the superficial fascia.[1] Subcutaneous emphysema has a characteristic crackling-feel to the touch, a sensation that has been described as similar to touching warm Rice Krispies.[2] This sensation of air under the skin is known as subcutaneous crepitation, a form of Crepitus.

| Subcutaneous emphysema | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Surgical emphysema, tissue emphysema, sub Q air |

| |

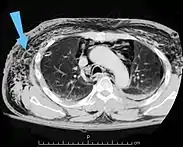

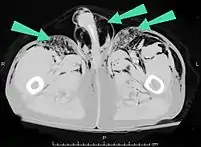

| An abdominal CT scan of a patient with subcutaneous emphysema (arrows) | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

Numerous etiologies of subcutaneous emphysema have been described. Pneumomediastinum was first recognized as a medical entity by Laennec, who reported it as a consequence of trauma in 1819. Later, in 1939, at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Dr. Louis Hamman described it in postpartum woman; indeed, subcutaneous emphysema is sometimes known as Hamman's syndrome. However, in some medical circles, it can instead be more commonly known as Macklin's Syndrome after L. Macklin, in 1939, and M.T. and C.C. Macklin, in 1944, who cumulatively went on to describe the pathophysiology in more detail.[3]

Subcutaneous emphysema can result from puncture of parts of the respiratory or gastrointestinal systems. Particularly in the chest and neck, air may become trapped as a result of penetrating trauma (e.g., gunshot wounds or stab wounds) or blunt trauma. Infection (e.g., gas gangrene) can cause gas to be trapped in the subcutaneous tissues. Subcutaneous emphysema can be caused by medical procedures and medical conditions that cause the pressure in the alveoli of the lung to be higher than that in the tissues outside of them.[4] Its most common causes are pneumothorax or a chest tube that has become occluded by a blood clot or fibrinous material. It can also occur spontaneously due to rupture of the alveoli, with dramatic presentation.[5] When the condition is caused by surgery it is called surgical emphysema.[6] The term spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema is used when the cause is not clear.[5] Subcutaneous emphysema is not typically dangerous in and of itself, however it can be a symptom of very dangerous underlying conditions, such as pneumothorax.[7] Although the underlying conditions require treatment, subcutaneous emphysema usually does not; small amounts of air are reabsorbed by the body. However, subcutaneous emphysema can be uncomfortable and may interfere with breathing, and is often treated by removing air from the tissues, for example by using large bore needles, skin incisions or subcutaneous catheterization.

Symptoms and signs

Signs and symptoms of spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema vary based on the cause, but it is often associated with swelling of the neck and chest pain, and may also involve sore throat, neck pain, difficulty swallowing, wheezing and difficulty breathing.[5] Chest X-rays may show air in the mediastinum, the middle of the chest cavity.[5] A significant case of subcutaneous emphysema is easy to detect by touching the overlying skin; it feels like tissue paper or Rice Krispies.[8] Touching the bubbles causes them to move and sometimes make a crackling noise.[9] The air bubbles, which are painless and feel like small nodules to the touch, may burst when the skin above them is palpated.[9] The tissues surrounding SCE are usually swollen. When large amounts of air leak into the tissues, the face can swell considerably.[8] In cases of subcutaneous emphysema around the neck, there may be a feeling of fullness in the neck, and the sound of the voice may change.[10] If SCE is particularly extreme around the neck and chest, the swelling can interfere with breathing. The air can travel to many parts of the body, including the abdomen and limbs, because there are no separations in the fatty tissue in the skin to prevent the air from moving.[11]

Causes

Trauma

Conditions that cause subcutaneous emphysema may result from both blunt and penetrating trauma;[5] SCE is often the result of a stabbing or gunshot wound.[12] Subcutaneous emphysema is often found in car accident victims because of the force of the crash.

Chest trauma, a major cause of subcutaneous emphysema, can cause air to enter the skin of the chest wall from the neck or lung.[9] When the pleural membranes are punctured, as occurs in penetrating trauma of the chest, air may travel from the lung to the muscles and subcutaneous tissue of the chest wall.[9] When the alveoli of the lung are ruptured, as occurs in pulmonary laceration, air may travel beneath the visceral pleura (the membrane lining the lung), to the hilum of the lung, up to the trachea, to the neck and then to the chest wall.[9] The condition may also occur when a fractured rib punctures a lung;[9] in fact, 27% of patients who have rib fractures also have subcutaneous emphysema.[11] Rib fractures may tear the parietal pleura, the membrane lining the inside of chest wall, allowing air to escape into the subcutaneous tissues.[13]

Subcutaneous emphysema is frequently found in pneumothorax (air outside of the lung in the chest cavity)[14][15] and may also result from air in the mediastinum, pneumopericardium (air in the pericardial cavity around the heart).[16] A tension pneumothorax, in which air builds up in the pleural cavity and exerts pressure on the organs within the chest, makes it more likely that air will enter the subcutaneous tissues through pleura torn by a broken rib.[13] When subcutaneous emphysema results from pneumothorax, air may enter tissues including those of the face, neck, chest, armpits, or abdomen.[1]

Pneumomediastinum can result from a number of events. For example, foreign body aspiration, in which someone inhales an object, can cause pneumomediastinum (and lead to subcutaneous emphysema) by puncturing the airways or by increasing the pressure in the affected lung(s) enough to cause them to burst.[17]

Subcutaneous emphysema of the chest wall is commonly among the first indications that barotrauma, damage caused by excessive pressure, has occurred;[1][18] it suggests that the lung was subjected to significant barotrauma.[19] Thus the phenomenon may occur in diving injuries.[5][20]

Trauma to parts of the respiratory system other than the lungs, such as rupture of a bronchial tube, may also cause subcutaneous emphysema.[13] Air may travel upward to the neck from a pneumomediastinum that results from a bronchial rupture, or downward from a torn trachea or larynx into the soft tissues of the chest.[13] It may also occur with fractures of the facial bones, neoplasms, during asthma attacks, when the Heimlich maneuver is used, and during childbirth.[5]

Injury with pneumatic tools, those that are driven by air, is also known to cause subcutaneous emphysema, even in extremities (the arms and legs).[21] It can also occur as a result of rupture of the esophagus; when it does, it is usually as a late sign.[22]

Medical treatment

Subcutaneous emphysema is a common result of certain types of surgery; for example it is not unusual in chest surgery.[8] It may also occur from surgery around the esophagus, and is particularly likely in prolonged surgery.[7] Other potential causes are positive pressure ventilation for any reason and by any technique, in which its occurrence is frequently unexpected. It may also occur as a result of oral surgery,[23] laparoscopy,[7] and cricothyrotomy. In a pneumonectomy, in which an entire lung is removed, the remaining bronchial stump may leak air, a rare but very serious condition that leads to progressive subcutaneous emphysema.[8] Air can leak out of the pleural space through an incision made for a thoracotomy to cause subcutaneous emphysema.[8] On infrequent occasions, the condition can result from dental surgery, usually due to use of high-speed tools that are air driven.[24] These cases result in usually painless swelling of the face and neck, with an immediate onset, the crepitus (crunching sound) typical of subcutaneous emphysema, and often with subcutaneous air visible on X-ray.[24]

One of the main causes of subcutaneous emphysema, along with pneumothorax, is an improperly functioning chest tube.[2] Thus subcutaneous emphysema is often a sign that something is wrong with a chest tube; it may be clogged, clamped, or out of place.[2] The tube may need to be replaced, or, when large amounts of air are leaking, a new tube may be added.[2]

Since mechanical ventilation can worsen a pneumothorax, it can force air into the tissues; when subcutaneous emphysema occurs in a ventilated patient, it is an indication that the ventilation may have caused a pneumothorax.[2] It is not unusual for subcutaneous emphysema to result from positive pressure ventilation.[25] Another possible cause is a ruptured trachea.[2] The trachea may be injured by tracheostomy or tracheal intubation; in cases of tracheal injury, large amounts of air can enter the subcutaneous space.[2] An endotracheal tube can puncture the trachea or bronchi and cause subcutaneous emphysema.[12]

Infection

Air can be trapped under the skin in necrotizing infections such as gangrene, occurring as a late sign in gas gangrene,[2] of which it is the hallmark sign. Subcutaneous emphysema is also considered a hallmark of fournier gangrene.[26] Symptoms of subcutaneous emphysema can result when infectious organisms produce gas by fermentation. When emphysema occurs due to infection, signs that the infection is systemic, i.e. that it has spread beyond the initial location, are also present.[9][21]

Pathophysiology

Air is able to travel to the soft tissues of the neck from the mediastinum and the retroperitoneum (the space behind the abdominal cavity) because these areas are connected by fascial planes.[4] From the punctured lungs or airways, the air travels up the perivascular sheaths and into the mediastinum, from which it can enter the subcutaneous tissues.[17]

Spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema is thought to result from increased pressures in the lung that cause alveoli to rupture.[5] In spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema, air travels from the ruptured alveoli into the interstitium and along the blood vessels of the lung, into the mediastinum and from there into the tissues of the neck or head.[5]

Diagnosis

Significant cases of subcutaneous emphysema are easy to diagnose because of the characteristic signs of the condition.[1] In some cases, the signs are subtle, making diagnosis more difficult.[13] Medical imaging is used to diagnose the condition or confirm a diagnosis made using clinical signs. On a chest radiograph, subcutaneous emphysema may be seen as radiolucent striations in the pattern expected from the pectoralis major muscle group. Air in the subcutaneous tissues may interfere with radiography of the chest, potentially obscuring serious conditions such as pneumothorax.[18] It can also reduce the effectiveness of chest ultrasound.[27] On the other hand, since subcutaneous emphysema may become apparent in chest X-rays before a pneumothorax does, its presence may be used to infer that of the latter injury.[13] Subcutaneous emphysema can also be seen in CT scans, with the air pockets appearing as dark areas. CT scanning is so sensitive that it commonly makes it possible to find the exact spot from which air is entering the soft tissues.[13] In 1994, M.T. Macklin and C.C. Macklin published further insights into the pathophysiology of spontaneous Macklin's Syndrome occurring from a severe asthmatic attack.

The presence of subcutaneous emphysema in a person who appears quite ill and febrile after bout of vomiting followed by left chest pain is very suggestive of the diagnosis of Boerhaave's syndrome, which is a life-threatening emergency caused by rupture of the distal esophagus.

Subcutaneous emphysema can be a complication of CO2 insufflation with laparoscopic surgery. A sudden rise in end-tidal CO2 following the initial rise that occurs with insufflation (first 15-30 min) should raise suspicion of subcutaneous emphysema.[4] Of note, there are no changes in the pulse oximetry or airway pressure in subcutaneous emphysema, unlike in endobronchial intubation, capnothorax, pneumothorax, or CO2 embolism.

Treatment

Subcutaneous emphysema is usually benign.[1] Most of the time, SCE itself does not need treatment (though the conditions from which it results may); however, if the amount of air is large, it can interfere with breathing and be uncomfortable.[28] It occasionally progresses to a state "Massive Subcutaneous Emphysema" which is quite uncomfortable and requires surgical drainage. When the amount of air pushed out of the airways or lung becomes massive, usually due to positive pressure ventilation, the eyelids swell so much that the patient cannot see. Also the pressure of the air may impede the blood flow to the areolae of the breast and skin of the scrotum or labia. This can lead to necrosis of the skin in these areas. The latter are urgent situations requiring rapid, adequate decompression.[29][30][31] Severe cases can compress the trachea and do require treatment.[32]

In severe cases of subcutaneous emphysema, catheters can be placed in the subcutaneous tissue to release the air.[1] Small cuts, or "blow holes", may be made in the skin to release the gas.[16] When subcutaneous emphysema occurs due to pneumothorax, a chest tube is frequently used to control the latter; this eliminates the source of the air entering the subcutaneous space.[2] If the volume of subcutaneous air is increasing, it may be that the chest tube is not removing air rapidly enough, so it may be replaced with a larger one.[8] Suction may also be applied to the tube to remove air faster.[8] The progression of the condition can be monitored by marking the boundaries with a special pencil for marking on skin.[32]

Since treatment usually involves dealing with the underlying condition, cases of spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema may require nothing more than bed rest, medication to control pain, and perhaps supplemental oxygen.[5] Breathing oxygen may help the body to absorb the subcutaneous air more quickly.[10]

Prognosis

Air in subcutaneous tissue does not usually pose a lethal threat;[4] small amounts of air are reabsorbed by the body.[8] Once the pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum that causes the subcutaneous emphysema is resolved, with or without medical intervention, the subcutaneous emphysema will usually clear.[18] However, spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema can, in rare cases, progress to a life-threatening condition,[5] and subcutaneous emphysema due to mechanical ventilation may induce ventilatory failure.[25]

History

The first report of subcutaneous emphysema resulting from air in the mediastinum was made in 1850 in a patient who had been coughing violently.[5] In 1900, the first recorded case of spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema was reported in a bugler for the Royal Marines who had had a tooth extracted: playing the instrument had forced air through the hole where the tooth had been and into the tissues of his face.[5] Since then, another case of spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema was reported in a submariner for the US Navy who had had a root canal in the past; the increased pressure in the submarine forced air through it and into his face. In recent years a case was reported at the University Hospital of Wales of a young man who had been coughing violently causing a rupture in the esophagus resulting in SE.[5] The cause of spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema was clarified between 1939 and 1944 by Macklin, contributing to the current understanding of the pathophysiology of the condition.[5]

References

- Papiris SA, Roussos C (2004). "Pleural disease in the intensive care unit". In Bouros D (ed.). Pleural Disease (Lung Biology in Health and Disease). Florida: Bendy Jean Baptiste. pp. 771–777. ISBN 978-0-8247-4027-6. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- Lefor, Alan T. (2002). Critical Care on Call. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division. pp. 238–240. ISBN 978-0-07-137345-6. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- Macklin, M. T; C. C Macklin (1944). "Malignant interstitial emphysema of the lungs and mediastinum as an important occult complication in many respiratory diseases and other conditions: an interpretation of the clinical literature in the light of laboratory experiment". Medicine. 23 (4): 281–358. doi:10.1097/00005792-194412000-00001. S2CID 56803581.

- Maunder RJ, Pierson DJ, Hudson LD (July 1984). "Subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management". Arch. Intern. Med. 144 (7): 1447–53. doi:10.1001/archinte.144.7.1447. PMID 6375617.

- Parker GS, Mosborg DA, Foley RW, Stiernberg CM (September 1990). "Spontaneous cervical and mediastinal emphysema". Laryngoscope. 100 (9): 938–940. doi:10.1288/00005537-199009000-00005. PMID 2395401. S2CID 21114664.

- Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary (6th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-19-860753-3.

- Brooks DR (1998). Current Review of Minimally Invasive Surgery. Philadelphia: Current Medicine. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-387-98338-7.

- Long BC, Cassmeyer V, Phipps WJ (1995). Adult Nursing: Nursing Process Approach. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-7234-2004-0. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- DeGowin RL, LeBlond RF, Brown DR (2004). DeGowin's Diagnostic Examination. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division. pp. 388, 552. ISBN 978-0-07-140923-0. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- NOAA (1991). NOAA Diving Manual. US Dept. of Commerce – National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 3.15. ISBN 978-0-16-035939-2. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- Schnyder P, Wintermark M (2000). Radiology of Blunt Trauma of the Chest. Berlin: Springer. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-3-540-66217-4. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- Peart O (2006). "Subcutaneous emphysema". Radiologic Technology. 77 (4): 296. PMID 16543482.

- Wicky S, Wintermark M, Schnyder P, Capasso P, Denys A (2000). "Imaging of blunt chest trauma". European Radiology. 10 (10): 1524–1538. doi:10.1007/s003300000435. PMID 11044920. S2CID 22311233.

- Hwang JC, Hanowell LH, Grande CM (1996). "Peri-operative concerns in thoracic trauma". Baillière's Clinical Anaesthesiology. 10 (1): 123–153. doi:10.1016/S0950-3501(96)80009-2.

- Myers JW, Neighbors M, Tannehill-Jones R (2002). Principles of Pathophysiology and Emergency Medical Care. Albany, N.Y: Delmar Thomson Learning. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-7668-2548-2. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- Grathwohl KW, Miller S (2004). "Anesthetic implications of minimally invasive urological surgery". In Bonnett R, Moore RG, Bishoff JT, Loenig S, Docimo SG (eds.). Minimally Invasive Urological Surgery. London: Taylor & Francis Group. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-84184-170-0. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- Findlay CA, Morrissey S, Paton JY (July 2003). "Subcutaneous emphysema secondary to foreign-body aspiration". Pediatric Pulmonology. 36 (1): 81–82. doi:10.1002/ppul.10295. PMID 12772230. S2CID 33808524.

- Criner GJ, D'Alonzo GE (2002). Critical Care Study Guide: text and review. Berlin: Springer. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-387-95164-5. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- Rankine JJ, Thomas AN, Fluechter D (July 2000). "Diagnosis of pneumothorax in critically ill adults". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 76 (897): 399–404. doi:10.1136/pmj.76.897.399. PMC 1741653. PMID 10878196.

- Raymond LW (June 1995). "Pulmonary barotrauma and related events in divers". Chest. 107 (6): 1648–52. doi:10.1378/chest.107.6.1648. PMID 7781361. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- van der Molen AB, Birndorf M, Dzwierzynski WW, Sanger JR (May 1999). "Subcutaneous tissue emphysema of the hand secondary to noninfectious etiology: a report of two cases". Journal of Hand Surgery. 24 (3): 638–41. doi:10.1053/jhsu.1999.0638. PMID 10357548.

- Kosmas EN, Polychronopoulos VS (2004). "Pleural effusions in gastrointestinal tract diseases". In Bouros D (ed.). Pleural Disease (Lung Biology in Health and Disease). New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker. p. 798. ISBN 978-0-8247-4027-6. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- Pan PH (1989). "Perioperative subcutaneous emphysema: Review of differential diagnosis, complications, management, and anesthetic implications". Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 1 (6): 457–459. doi:10.1016/0952-8180(89)90011-1. PMID 2696508.

- Monsour PA, Savage NW (October 1989). "Cervicofacial emphysema following dental procedures". Australian Dental Journal. 34 (5): 403–406. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.1989.tb00695.x. PMID 2684113.

- Conetta R, Barman AA, Iakovou C, Masakayan RJ (September 1993). "Acute ventilatory failure from massive subcutaneous emphysema". Chest. 104 (3): 978–980. doi:10.1378/chest.104.3.978. PMID 8365332. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- Levenson RB, Singh AK, Novelline RA (2008). "Fournier gangrene: Role of imaging". Radiographics. 28 (2): 519–528. doi:10.1148/rg.282075048. PMID 18349455.

- Gravenstein N, Lobato E, Kirby RM (2007). Complications in Anesthesiology. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-7817-8263-0. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- Abu-Omar Y, Catarino PA (February 2002). "Progressive subcutaneous emphysema and respiratory arrest". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 95 (2): 90–91. doi:10.1177/014107680209500210. PMC 1279319. PMID 11823553.

- Maunder, R J; D J Pierson; L D Hudson (July 1984). "Subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management". Archives of Internal Medicine. 144 (7): 1447–1453. doi:10.1001/archinte.144.7.1447. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 6375617.

- Romero, Kleber J; Máximo H Trujillo (2010-04-21). "Spontaneous pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in asthma exacerbation: The Macklin effect". Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care. 39 (5): 444–7. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.10.001. ISSN 1527-3288. PMID 20561891.

- Ito, Takeo; Koichi Goto; Kiyotaka Yoh; Seiji Niho; Hironobu Ohmatsu; Kaoru Kubota; Kanji Nagai; Eishi Miyazaki; Toshihide Kumamoto; Yutaka Nishiwaki (July 2010). "Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy as a paraneoplastic manifestation of lung cancer". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 5 (7): 976–980. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181dc1f3c. ISSN 1556-1380. PMID 20453688. S2CID 2989121.

- Carpenito-Moyet LJ (2004). Nursing Care Plans and Documentation: Nursing Diagnoses and Collaborative Problems. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 889. ISBN 978-0-7817-3906-1. Retrieved 2008-05-12.