Supraoptic nucleus

The supraoptic nucleus (SON) is a nucleus of magnocellular neurosecretory cells in the hypothalamus of the mammalian brain. The nucleus is situated at the base of the brain, adjacent to the optic chiasm. In humans, the SON contains about 3,000 neurons.

| Supraoptic nucleus | |

|---|---|

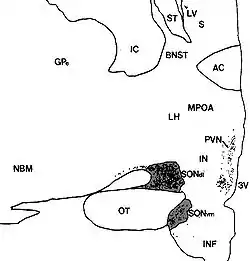

Human supraoptic nucleus (SON, dorsolateral and ventromedial components) in this coronal section is indicated by the shaded areas. Dots represent vasopressin (AVP) neurons (also seen in the paraventricular nucleus, PVN). The medial surface is the 3rd ventricle (3V), with more lateral to the left. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nucleus supraopticus |

| MeSH | D013495 |

| NeuroNames | 385 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1411 |

| TA98 | A14.1.08.912 |

| TA2 | 5721 |

| FMA | 62317 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Function

The cell bodies produce the peptide hormone vasopressin, which is also known as anti-diuretic hormone (ADH), and the peptide hormone oxytocin.[1] Both of these peptides are released from the posterior pituitary. ADH travels via the bloodstream to its target cells in the papillary ducts in the kidneys, enhancing water reabsorption. OT travels via the bloodstream to act at the mammary glands and the uterus.

In the cell bodies, the hormones are packaged in large, membrane-bound vesicles that are transported down the axons to the nerve endings. The secretory granules are also stored in packets along the axon called Herring bodies.

Similar magnocellular neurons are also found in the paraventricular nucleus.

Signaling

Each neuron in the nucleus has one long axon that projects to the posterior pituitary gland, where it gives rise to about 10,000 neurosecretory nerve terminals. The magnocellular neurons are electrically excitable: In response to afferent stimuli from other neurons, they generate action potentials, which propagate down the axons. When an action potential invades a neurosecretory terminal, the terminal is depolarised, and calcium enters the terminal through voltage-gated channels. The calcium entry triggers the secretion of some of the vesicles by a process known as exocytosis. The vesicle contents are released into the extracellular space, from where they diffuse into the bloodstream.[2]

Regulation of supraoptic neurons

Vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone, ADH) is released in response to solute concentration in the blood, decreased blood volume, or blood pressure.

Some other inputs come from the brainstem, including from some of the noradrenergic neurons of the nucleus of the solitary tract and the ventrolateral medulla. However, many of the direct inputs to the supraoptic nucleus come from neurons just outside the nucleus (the "perinuclear zone").

Of the afferent inputs to the supraoptic nucleus, most contain either the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA or the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, but these transmitters often co-exist with various peptides. Other afferent neurotransmitters include noradrenaline (from the brainstem), dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine.

The supraoptic nucleus as a "model system"

The supraoptic nucleus is an important "model system" in neuroscience. There are many reasons for this: Some technical advantages of working on the supraoptic nucleus are that the cell bodies are relatively large, the cells make exceptionally large amounts of their secretory products, and the nucleus is relatively homogeneous and easy to separate from other brain regions. The gene expression and electrical activity of supraoptic neurons has been studied extensively, in many physiological and experimental conditions.[3] These studies have led to many insights of general importance, as in the examples below.

Morphological plasticity in the supraoptic nucleus

Anatomical studies using electron microscopy have shown that the morphology of the supraoptic nucleus is remarkably adaptable.[4][5][6]

For example, during lactation there are large changes in the size and shape of the oxytocin neurons, in the numbers and types of synapses that these neurons receive, and in the structural relationships between neurons and glial cells in the nucleus. These changes arise during parturition, and are thought to be important adaptations that prepare the oxytocin neurons for a sustained high demand for oxytocin. Oxytocin is essential for milk let-down in response to suckling.

These studies showed that the brain is much more "plastic" in its anatomy than previously recognized, and led to great interest in the interactions between glial cells and neurons in general.

Stimulus-secretion coupling

In response to, for instance, a rise in the plasma sodium concentration, vasopressin neurons also discharge action potentials in bursts, but these bursts are much longer and are less intense than the bursts displayed by oxytocin neurons, and the bursts in vasopressin cells are not synchronised.[7]

It seemed strange that the vasopressin cells should fire in bursts. As the activity of the vasopressin cells is not synchronised, the overall level of vasopressin secretion into the blood is continuous, not pulsatile. Richard Dyball and his co-workers speculated that this pattern of activity, called "phasic firing", might be particularly effective for causing vasopressin secretion. They showed this to be the case[8] by studying vasopressin secretion from the isolated posterior pituitary gland in vitro. They found that vasopressin secretion could be evoked by electrical stimulus pulses applied to the gland, and that much more hormone was released by a phasic pattern of stimulation than by a continuous pattern of stimulation.

These experiments led to interest in "stimulus-secretion coupling" - the relationship between electrical activity and secretion. Supraoptic neurons are unusual because of the large amounts of peptide that they secrete, and because they secrete the peptides into the blood. However, many neurons in the brain, and especially in the hypothalamus, synthesize peptides. It is now thought that bursts of electrical activity might be generally important for releasing large amounts of peptide from peptide-secreting neurons.

Dendritic secretion

Supraoptic neurons have typically 1-3 large dendrites, most of which projecting ventrally to form a mat of process at the base of the nucleus, called the ventral glial lamina. The dendrites receive most of the synaptic terminals from afferent neurons that regulate the supraoptic neurons, but neuronal dendrites are often actively involved in information processing, rather than being simply passive receivers of information. The dendrites of supraoptic neurons contain large numbers of neurosecretory vesicles that contain oxytocin and vasopressin, and they can be released from the dendrites by exocytosis. The oxytocin and vasopressin that is released at the posterior pituitary gland enters the blood, and cannot re-enter the brain because the blood–brain barrier does not allow oxytocin and vasopressin through, but the oxytocin and vasopressin that is released from dendrites acts within the brain. Oxytocin neurons themselves express oxytocin receptors, and vasopressin neurons express vasopressin receptors, so dendritically-released peptides "autoregulate" the supraoptic neurons. Francoise Moos and Phillipe Richard first showed that the autoregulatory action of oxytocin is important for the milk-ejection reflex.

These peptides have relatively long half-lives in the brain (about 20 minutes in the CSF), and they are released in large amounts in the supraoptic nucleus, and so they are available to diffuse through the extracellular spaces of the brain to act at distant targets. Oxytocin and vasopressin receptors are present in many other brain regions, including the amygdala, brainstem, and septum, as well as most nuclei in the hypothalamus.

Because so much vasopressin and oxytocin are released at this site, studies of the supraoptic nucleus have made an important contribution to understanding how release from dendrites is regulated, and in understanding its physiological significance. Studies have demonstrated that secretin helps to facilitate dendritic oxytocin release in the SON, and that secretin administration into the SON enhances social recognition in rodents. This enhanced social capability appears to be working through secretin's effects on oxytocin neurons in the SON, as blocking oxytocin receptors in this region blocks social recognition.[9]

Co-existing peptides

Vasopressin neurons and oxytocin neurons make many other neuroactive substances in addition to vasopressin and oxytocin, though most are present only in small quantities. However, some of these other substances are known to be important. Dynorphin produced by vasopressin neurons is involved in regulating the phasic discharge patterning of vasopressin neurons, and nitric oxide produced by both neuronal types is a negative-feedback regulator of cell activity. Oxytocin neurons also make dynorphin; in these neurons, dynorphin acts at the nerve terminals in the posterior pituitary as a negative feedback inhibitor of oxytocin secretion. Oxytocin neurons also make large amounts of cholecystokinin as well as the cocaine and amphetamine regulatory transcript (CART).

See also

References

- Ishuina, Tatjana (1999). "Vasopressin and Oxytocin Neurons of the Human Supraoptic and Paraventricular Nucleus; Size Changes in Relation to Age and Sex". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism – via CrossRef.

- Marieb, Elaine (2014). Anatomy & physiology. Glenview, IL: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 978-0-321-86158-0.

- Burbach, J. Peter H.; Luckman, Simon M.; Murphy, David; Gainer, Harold (2001). "Gene regulation in the magnocellular hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system". Physiological Reviews. 81 (3): 1197–1267. doi:10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1197. PMID 11427695.

- Theodosis, Dionysia T. (January 2002). "Oxytocin-secreting neurons: A physiological model of morphological neuronal and glial plasticity in the adult hypothalamus". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 23 (1): 101–135. doi:10.1006/frne.2001.0226. PMID 11906204.

- Hatton, Glenn I. (March 2004). "Dynamic neuronal-glial interactions: an overview 20 years later". Peptides. 25 (3): 403–411. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2003.12.001. PMID 15134863.

- Tasker JG, Di S, Boudaba C (2002). "Functional synaptic plasticity in hypothalamic magnocellular neurons". Prog. Brain Res. Progress in Brain Research. 139: 113–9. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(02)39011-3. ISBN 9780444509826. PMID 12436930.

- Armstrong WE, Stern JE (1998). "Phenotypic and state-dependent expression of the electrical and morphological properties of oxytocin and vasopressin neurones". Prog. Brain Res. Progress in Brain Research. 119: 101–13. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(08)61564-2. ISBN 9780444500809. PMID 10074783.

- Dutton, A.; Dyball, R. E. J. (1979). "Phasic firing enhances vasopressin release from the rat neurohypophysis". Journal of Physiology. 290 (2): 433–440. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012781. PMC 1278845. PMID 469785.

- Takayanagi, Yuki; Yoshida, Masahide; Takashima, Akihide; Takanami, Keiko; Yoshida, Shoma; Nishimori, Katsuhiko; Nishijima, Ichiko; Sakamoto, Hirotaka; Yamagata, Takanori; Onaka, Tatsushi (December 2015). "Activation of Supraoptic Oxytocin Neurons by Secretin Facilitates Social Recognition". Biological Psychiatry. 81 (3): 243–251. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.11.021. PMID 26803341.