Suprachiasmatic nucleus

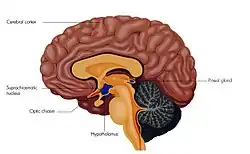

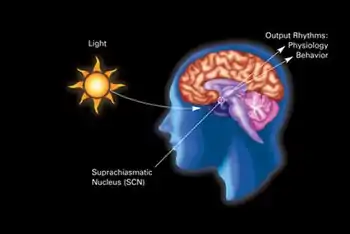

The suprachiasmatic nucleus or nuclei (SCN) is a tiny region of the brain in the hypothalamus, situated directly above the optic chiasm. It is responsible for controlling circadian rhythms. The neuronal and hormonal activities it generates regulate many different body functions in a 24-hour cycle. The mouse SCN contains approximately 20,000 neurons.[1]

| Suprachiasmatic nucleus | |

|---|---|

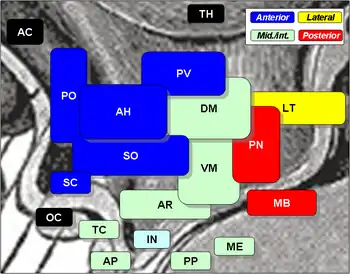

Suprachiasmatic nucleus is SC, at center left, labelled in blue. The optic chiasm is OC, just below, labelled in black. | |

Suprachiasmatic nucleus is labelled and shown in green. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nucleus suprachiasmaticus |

| MeSH | D013493 |

| NeuroNames | 384 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1325 |

| TA98 | A14.1.08.911 |

| TA2 | 5720 |

| FMA | 67883 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The SCN interacts with many other regions of the brain. It contains several cell types and several different peptides (including vasopressin and vasoactive intestinal peptide) and neurotransmitters.

Neuroanatomy

The SCN is situated in the anterior part of the hypothalamus immediately dorsal, or superior (hence supra) to the optic chiasm (CHO) bilateral to (on either side of) the third ventricle.

The nucleus can be divided into ventrolateral and dorsolateral portions, also known as the core and shell, respectively. These regions differ in their expression of the clock genes, the core expresses them in response to stimuli whereas the shell expresses them constitutively.

In terms of projections, the core receives innervation via three main pathways, the retinohypothalamic tract, geniculohypothalamic tract, and projections from some raphe nuclei. Dorsomedial SCN is mainly innervated by the core and also by other hypothalamic areas. Lastly, its output is mainly to the subparaventricular zone and dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus which both mediate the influence SCN exerts over circadian regulation of the body.

Circadian effects

Different organisms such as bacteria,[2] plants, fungi, and animals, show genetically based near-24-hour rhythms. Although all of these clocks appear to be based on a similar type of genetic feedback loop, the specific genes involved are thought to have evolved independently in each kingdom. Many aspects of mammalian behavior and physiology show circadian rhythmicity, including sleep, physical activity, alertness, hormone levels, body temperature, immune function, and digestive activity. The SCN coordinates these rhythms across the entire body, and rhythmicity is lost if the SCN is destroyed. For example, total time of sleep is maintained in rats with SCN damage, but the length and timing of sleep episodes becomes erratic. The SCN maintains control across the body by synchronizing "slave oscillators," which exhibit their own near-24-hour rhythms and control circadian phenomena in local tissue.[3]

The SCN receives input from specialized photosensitive ganglion cells in the retina via the retinohypothalamic tract. Neurons in the ventrolateral SCN (vlSCN) have the ability for light-induced gene expression. Melanopsin-containing ganglion cells in the retina have a direct connection to the ventrolateral SCN via the retinohypothalamic tract. When the retina receives light, the vlSCN relays this information throughout the SCN allowing entrainment, synchronization, of the person's or animal's daily rhythms to the 24-hour cycle in nature. The importance of entraining organisms, including humans, to exogenous cues such as the light/dark cycle, is reflected by several circadian rhythm sleep disorders, where this process does not function normally.[4]

Neurons in the dorsomedial SCN (dmSCN) are believed to have an endogenous 24-hour rhythm that can persist under constant darkness (in humans averaging about 24 hours 11 min).[5] A GABAergic mechanism is involved in the coupling of the ventral and dorsal regions of the SCN.[6]

The SCN sends information to other hypothalamic nuclei and the pineal gland to modulate body temperature and production of hormones such as cortisol and melatonin.

Circadian rhythms of endothermic (warm-blooded) and ectothermic (cold-blooded) vertebrates

Information about the direct neuronal regulation of metabolic processes and circadian rhythm-controlled behaviors is not well known among either endothermic or ectothermic vertebrates, although extensive research has been done on the SCN in model animals such as the mammalian mouse and ectothermic reptiles, in particular, lizards. The SCN is known to be involved not only in photoreception through innervation from the retinohypothalamic tract but also in thermoregulation of vertebrates capable of homeothermy, as well as regulating locomotion and other behavioral outputs of the circadian clock within ectothermic vertebrates.[7] The behavioral differences between both classes of vertebrates, when compared to the respective structures and properties of the SCN and various other nuclei proximate to the hypothalamus, provide insight into how these behaviors are the consequence of differing circadian regulation. Ultimately, many neuroethological studies must be done to completely ascertain the direct and indirect roles of the SCN on circadian-regulated behaviors of vertebrates.

The SCN of endotherms and ectotherms

In general, external temperature does not influence endothermic animal behavior or circadian rhythm because of the ability of these animals to keep their internal body temperature constant through homeostatic thermoregulation; however, peripheral oscillators (see Circadian rhythm) in mammals are sensitive to temperature pulses and will experience resetting of the circadian clock phase and associated genetic expression, suggesting how peripheral circadian oscillators may be separate entities from one another despite having a master oscillator within the SCN. Furthermore, when individual neurons of the SCN from a mouse were treated with heat pulses, a similar resetting of oscillators was observed, but when an intact SCN was treated with the same heat pulse treatment the SCN was resistant to temperature change by exhibiting an unaltered circadian oscillating phase.[7] In ectothermic animals, particularly the ruin lizard Podacris sicula, temperature has been shown to affect the circadian oscillators within the SCN.[8] This reflects a potential evolutionary relationship among endothermic and ectothermic vertebrates, in how ectotherms rely on environmental temperature to affect their circadian rhythms and behavior and endotherms have an evolved SCN to essentially ignore external temperature and use photoreception as a means for entraining the circadian oscillators within their SCN. In addition, the differences of the SCN between endothermic and ectothermic vertebrates suggest that the neuronal organization of the temperature-resistant SCN in endotherms is responsible for driving thermoregulatory behaviors in those animals differently from those of ectotherms, since they rely on external temperature for engaging in certain behaviors.

Behaviors controlled by the SCN of vertebrates

Significant research has been conducted on the genes responsible for controlling circadian rhythm, in particular within the SCN. Knowledge of the gene expression of Clock (Clk) and Period2 (Per2), two of the many genes responsible for regulating circadian rhythm within the individual cells of the SCN, has allowed for a greater understanding of how genetic expression influences the regulation of circadian rhythm-controlled behaviors. Studies on thermoregulation of ruin lizards and mice have informed some connections between the neural and genetic components of both vertebrates when experiencing induced hypothermic conditions. Certain findings have reflected how evolution of SCN both structurally and genetically has resulted in the engagement of characteristic and stereotyped thermoregulatory behavior in both classes of vertebrates.

- Mice: Among vertebrates, it is known that mammals are endotherms that are capable of homeostatic thermoregulation. Mice have been shown to have some thermosensitivity within the SCN, although the regulation of body temperature by mice experiencing hypothermia is more sensitive to whether they are in a bright or dark environment; it has been shown that mice in darkened conditions and experiencing hypothermia maintain a stable internal body temperature, even while fasting. In light conditions, mice showed a drop in body temperature under the same fasting and hypothermic conditions. Through analyzing genetic expression of Clock genes in wild-type and knockout strains, as well as analyzing the activity of neurons within the SCN and connections to proximate nuclei of the hypothalamus in the aforementioned conditions, it has been shown that the SCN is the center of control for circadian body temperature rhythm.[9] This circadian control, thus, includes both direct and indirect influence of many of the thermoregulatory behaviors that mammals engage in to maintain homeostasis.

- Ruin lizards: Several studies have been conducted on the genes expressed in circadian oscillating cells of the SCN during various light and dark conditions, as well as effects from inducing mild hypothermia in reptiles. In terms of structure, the SCNs of lizards have a closer resemblance to those of mice, possessing a dorsomedial portion and a ventrolateral core.[10] However, genetic expression of the circadian-related Per2 gene in lizards is similar to that in reptiles and birds, despite the fact that birds have been known to have a distinct SCN structure consisting of a lateral and medial portion.[11] Studying the lizard SCN because of the lizard's small body size and ectothermy is invaluable to understanding how this class of vertebrates modifies its behavior within the dynamics of circadian rhythm, but it has not yet been determined whether the systems of cold-blooded vertebrates were slowed as a result of decreased activity in the SCN or showed decreases in metabolic activity as a result of hypothermia.[8]

Other signals from the retina

The SCN is one of many nuclei that receive nerve signals directly from the retina.

Some of the others are the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), the superior colliculus, the basal optic system, and the pretectum:

- The LGN passes information about color, contrast, shape, and movement on to the visual cortex and itself signals to the SCN.

- The superior colliculus controls the movement and orientation of the eye.

- The basal optic system also controls eye movements.[12]

- The pretectum controls the size of the pupil.

Gene expression

The circadian rhythm in the SCN is generated by a gene expression cycle in individual SCN neurons. This cycle has been well conserved through evolution and in essence is similar in cells from many widely different organisms that show circadian rhythms. For example, although fruit flies (like all invertebrates) do not have an SCN, the cycle is largely similar to that of mammals. It is currently thought that all animals share a common root in their circadian rhythm.[13]

Fruitfly

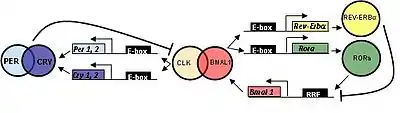

In the fruitfly Drosophila, the cellular circadian rhythm in neurons is controlled by two interlocked feedback loops.

- In the first loop, the bHLH transcription factors clock (CLK) and cycle (CYC) drive the transcription of their own repressors period (PER) and timeless (TIM). PER and TIM proteins then accumulate in the cytoplasm, translocate into the nucleus at night, and turn off their own transcription, thereby setting up a 24-hour oscillation of transcription and translation.

- In the second loop, the transcription factors vrille (VRI) and Pdp1 are initiated by CLK/CYC. PDP1 acts positively on CLK transcription and negatively on VRI.

These genes encode various transcription factors that trigger expression of other proteins. The products of clock and cycle, called CLK and CYC, belong to the PAS-containing subfamily of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family of transcription factors, and form a heterodimer. This heterodimer (CLK-CYC) initiates the transcription of PER and TIM, whose protein products dimerize and then inhibit their own expression by disrupting CLK-CYC-mediated transcription. This negative feedback mechanism gives a 24-hour rhythm in the expression of the clock genes. Many genes are suspected to be linked to circadian control by "E-box elements" in their promoters, as CLK-CYC and its homologs bind to these elements.

The 24-hour rhythm could be reset by light via the protein cryptochrome (CRY), which is involved in the circadian photoreception in Drosophila. CRY associates with TIM in a light-dependent manner that leads to the destruction of TIM. Without the presence of TIM for stabilization, PER is eventually destroyed during the day. As a result, the repression of CLK-CYC is reduced and the whole cycle reinitiates again.

Mammals

In mammals, circadian clock genes behave in a manner similar to that of flies.

CLOCK (circadian locomotor output cycles kaput) was first cloned in mouse and BMAL1 (brain and muscle aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT)-like 1) is the primary homolog of Drosophila CYC.

Three homologs of PER (PER1, PER2, and PER3) and two CRY homologs (CRY1 and CRY2) have been identified.

TIM has been identified in mammals; however, its function is still not determined. Mutations in TIM result in an inability to respond to zeitgebers, which is essential for resetting the biological clock.

Recent research suggests that, outside the SCN, clock genes may have other important roles as well, including their influence on the effects of drugs of abuse such as cocaine.[14][15]

Electrophysiology

Neurons in the SCN fire action potentials in a 24-hour rhythm. At mid-day, the firing rate reaches a maximum, and, during the night, it falls again. How the gene expression cycle (so-called the core clock) connects to the neural firing remains unknown.

Many SCN neurons are sensitive to light stimulation via the retina, and sustainedly firing action potentials during a light pulse (~30 seconds) in rodents. The photic response is likely linked to effects of light on circadian rhythms. In addition, focal application of melatonin can decrease firing activity of these neurons, suggesting that melatonin receptors present in the SCN mediate phase-shifting effects through the SCN.

See also

References

- Fahey J (2009-10-15). "How Your Brain Tells Time". Out Of The Labs. Forbes.

- Clodong S, Dühring U, Kronk L, Wilde A, Axmann I, Herzel H, Kollmann M (2007). "Functioning and robustness of a bacterial circadian clock". Molecular Systems Biology. 3 (1): 90. doi:10.1038/msb4100128. PMC 1847943. PMID 17353932.

- Bernard S, Gonze D, Cajavec B, Herzel H, Kramer A (April 2007). "Synchronization-induced rhythmicity of circadian oscillators in the suprachiasmatic nucleus". PLOS Computational Biology. 3 (4): e68. Bibcode:2007PLSCB...3...68B. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030068. PMC 1851983. PMID 17432930.

- Reid KJ, Chang AM, Zee PC (May 2004). "Circadian rhythm sleep disorders". The Medical Clinics of North America. 88 (3): 631–51, viii. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2004.01.010. PMC 3523094. PMID 15087208.

- "Human Biological Clock Set Back an Hour". Harvard Gazette. 1999-07-15. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- Azzi, A; Evans, JA; Leise, T; Myung, J; Takumi, T; Davidson, AJ; Brown, SA (18 January 2017). "Network Dynamics Mediate Circadian Clock Plasticity". Neuron. 93 (2): 441–450. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.022. PMC 5247339. PMID 28065650.

- Buhr ED, Yoo SH, Takahashi JS (October 2010). "Temperature as a universal resetting cue for mammalian circadian oscillators". Science. 330 (6002): 379–85. Bibcode:2010Sci...330..379B. doi:10.1126/science.1195262. PMC 3625727. PMID 20947768.

- Magnone MC, Jacobmeier B, Bertolucci C, Foà A, Albrecht U (February 2005). "Circadian expression of the clock gene Per2 is altered in the ruin lizard (Podarcis sicula) when temperature changes" (PDF). Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 133 (2): 281–5. doi:10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.10.014. PMID 15710245.

- Tokizawa K, Uchida Y, Nagashima K (December 2009). "Thermoregulation in the cold changes depending on the time of day and feeding condition: physiological and anatomical analyses of involved circadian mechanisms". Neuroscience. 164 (3): 1377–86. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.040. PMID 19703527. S2CID 207246725.

- Casini G, Petrini P, Foà A, Bagnoli P (1993). "Pattern of organization of primary visual pathways in the European lizard Podarcis sicula Rafinesque". Journal für Hirnforschung. 34 (3): 361–74. PMID 7505790.

- Abraham U, Albrecht U, Gwinner E, Brandstätter R (August 2002). "Spatial and temporal variation of passer Per2 gene expression in two distinct cell groups of the suprachiasmatic hypothalamus in the house sparrow (Passer domesticus)". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 16 (3): 429–36. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02102.x. PMID 12193185. S2CID 15282323.

- Giolli RA, Blanks RH, Lui F (2006). "The accessory optic system: basic organization with an update on connectivity, neurochemistry, and function" (PDF). Neuroanatomy of the Oculomotor System. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 151. pp. 407–40. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(05)51013-6. ISBN 9780444516961. PMID 16221596.

- Young, Michael W.; Kay, Steve A. (September 2001). "Time zones: a comparative genetics of circadian clocks". Nature Reviews Genetics. 2 (9): 702–715. doi:10.1038/35088576. PMID 11533719. S2CID 13286388.

- Yuferov V, Butelman ER, Kreek MJ (October 2005). "Biological clock: biological clocks may modulate drug addiction". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (10): 1101–3. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201483. PMID 16094306. S2CID 26531678.

- Manev H, Uz T (January 2006). "Clock genes as a link between addiction and obesity". European Journal of Human Genetics. 14 (1): 5. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201524. PMID 16288309.