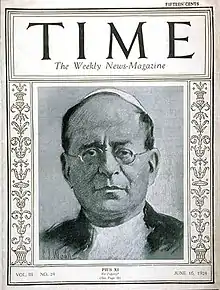

Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (Italian: Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti[lower-alpha 1] (Italian: [amˈbrɔ:dʒo daˈmja:no aˈkille ˈratti]; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City from its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929. He assumed as his papal motto "Pax Christi in Regno Christi," translated "The Peace of Christ in the Kingdom of Christ."

Pius XI | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

.jpg.webp) Portrait by Nicola Perscheid, c. 1922 | |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Papacy began | 6 February 1922 |

| Papacy ended | 10 February 1939 |

| Predecessor | Benedict XV |

| Successor | Pius XII |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 20 December 1879 by Raffaele Monaco La Valletta |

| Consecration | 28 October 1919 by Aleksander Kakowski |

| Created cardinal | 13 June 1921 by Benedict XV |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti 31 May 1857 Desio, Lombardy–Venetia, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 10 February 1939 (aged 81) Apostolic Palace, Vatican City |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Education | Pontifical Gregorian University (ThD, JCD, PhD) |

| Motto | Raptim Transit ("It goes by swiftly", Job 6:15)[1] Pax Christi in Regno Christi (The Peace of Christ in the Realm of Christ)[2] |

| Signature |  |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Other popes named Pius | |

Ordination history of Pope Pius XI | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Pius XI issued numerous encyclicals, including Quadragesimo anno on the 40th anniversary of Pope Leo XIII's groundbreaking social encyclical Rerum novarum, highlighting the capitalistic greed of international finance, the dangers of socialism/communism, and social justice issues, and Quas primas, establishing the feast of Christ the King in response to anti-clericalism. The encyclical Studiorum ducem, promulgated 29 June 1923, was written on the occasion of the 6th centenary of the canonization of Thomas Aquinas, whose thought is acclaimed as central to Catholic philosophy and theology. The encyclical also singles out the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum as the preeminent institution for the teaching of Aquinas: "ante omnia Pontificium Collegium Angelicum, ubi Thomam tamquam domi suae habitare dixeris" (before all others the Pontifical Angelicum College, where Thomas can be said to dwell).[3][4]

To establish or maintain the position of the Catholic Church, Pius XI concluded a record number of concordats, including the Reichskonkordat with Nazi Germany, whose betrayals of which he condemned four years later in the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge ("With Burning Concern"). During his pontificate, the longstanding hostility with the Italian government over the status of the papacy and the Church in Italy was successfully resolved in the Lateran Treaty of 1929. He was unable to stop the persecution of the Church and the killing of clergy in Mexico, Spain and the Soviet Union. He canonized important saints, including Thomas More, Peter Canisius, Bernadette of Lourdes and Don Bosco. He beatified and canonized Thérèse de Lisieux, for whom he held special reverence, and gave equivalent canonization to Albertus Magnus, naming him a Doctor of the Church due to the spiritual power of his writings. He took a strong interest in fostering the participation of lay people throughout the Catholic Church, especially in the Catholic Action movement. The end of his pontificate was dominated by speaking out against Hitler and Mussolini, and defending the Catholic Church from intrusions into Catholic life and education.

Pius XI died on 10 February 1939 in the Apostolic Palace and is buried in the Papal Grotto of Saint Peter's Basilica. In the course of excavating space for his tomb, two levels of burial grounds were uncovered which revealed bones now venerated as the bones of St. Peter.[5][6][7]

Early life and career

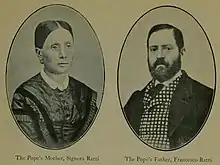

Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti was born in Desio, in the province of Milan, in 1857, the son of an owner of a silk factory.[8] His parents were Francesco and Teresa; his siblings were Carlo (1853–1906), Fermo (1854–1929),[9] Edoardo (1855–96), Camilla (1860–?), and Cipriano. He was ordained a priest in 1879 and embarked on an academic career within the Church. He obtained three doctorates (in philosophy, canon law and theology) at the Gregorian University in Rome, and then from 1882 to 1888 was a professor at the seminary in Padua. His scholarly specialty was as an expert paleographer, a student of ancient and medieval Church manuscripts. Eventually, he left seminary teaching to work full-time at the Ambrosian Library in Milan, from 1888 to 1911.[10]

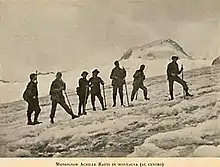

During this time, Ratti edited and published an edition of the Ambrosian Missal (the rite of Mass used in Milan), and researched and wrote much on the life and works of St. Charles Borromeo. He became chief of the Library in 1907 and undertook a thorough programme of restoration and re-classification of the Ambrosian's collection. He was also an avid mountaineer in his spare time, reaching the summits of Monte Rosa, the Matterhorn, Mont Blanc and Presolana. The combination of a scholar-athlete pope would not be seen again until the pontificate of John Paul II. In 1911, at Pope Pius X's (1903–1914) invitation, he moved to the Vatican to become Vice-Prefect of the Vatican Library, and in 1914 was promoted to Prefect.[11]

Nuncio to Poland and expulsion

.jpg.webp)

In 1918, Pope Benedict XV (1914–1922) asked Ratti to change careers and take a diplomatic post: apostolic visitor (that is, unofficial papal representative) in Poland, a state newly restored to existence, but still under effective German and Austro-Hungarian control. In October 1918, Benedict was the first head of state to congratulate the Polish people on the occasion of the restoration of their independence.[12] In March 1919, he nominated ten new bishops and, soon after, upgraded Ratti's position in Warsaw to the official position of papal nuncio.[12] Ratti was consecrated as a titular archbishop in October 1919.

Benedict XV and Ratti repeatedly cautioned Polish authorities against persecuting the Lithuanian and Ruthenian clergy.[13] During the Bolshevik advance against Warsaw, the Pope asked for worldwide public prayers for Poland, while Ratti was the only foreign diplomat who refused to flee Warsaw when the Red Army was approaching the city in August 1920.[14] On 11 June 1921, Benedict XV asked Ratti to deliver his message to the Polish episcopate, warning against political misuses of spiritual power, urging again peaceful coexistence with neighbouring people, stating that "love of country has its limits in justice and obligations".[15]

Ratti intended to work for Poland by building bridges to men of goodwill in the Soviet Union, even to shedding his blood for Russia.[16] Benedict, however, needed Ratti as a diplomat, not as a martyr, and forbade his traveling into the USSR despite his being the official papal delegate for Russia.[16] The nuncio's continued contacts with Russians did not generate much sympathy for him within Poland at the time. After Pope Benedict sent Ratti to Silesia to forestall potential political agitation within the Polish Catholic clergy,[13] the nuncio was asked to leave Poland. On 20 November, when German Cardinal Adolf Bertram announced a papal ban on all political activities of clergymen, calls for Ratti's expulsion climaxed.[17] Ratti was asked to leave. "While he tried honestly to show himself as a friend of Poland, Warsaw forced his departure, after his neutrality in Silesian voting was questioned"[18] by Germans and Poles. Nationalistic Germans objected to the Polish nuncio supervising local elections, and patriotic Poles were upset because he curtailed political action among the clergy.[17]

Elevation to the papacy

In the consistory of 3 June 1921, Pope Benedict XV created three new cardinals, including Ratti, who was appointed Archbishop of Milan simultaneously. The pope joked with them, saying, "Well, today I gave you the red hat, but soon it will be white for one of you."[19] After the Vatican celebration, Ratti went to the Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino for a retreat to prepare spiritually for his new role. He accompanied Milanese pilgrims to Lourdes in August 1921.[19] Ratti received a tumultuous welcome on a visit to his home town Desio, and was enthroned in Milan on 8 September. On 22 January 1922, Pope Benedict XV died unexpectedly of pneumonia.[20]

At the conclave to choose a new pope, which proved to be the longest of the 20th century, the College of Cardinals was divided into two factions, one led by Rafael Merry del Val favoring the policies and style of Pope Pius X and the other favoring those of Pope Benedict XV led by Pietro Gasparri.[21]

Gasparri approached Ratti before voting began on the third day and told him he would urge his supporters to switch their votes to Ratti, who was shocked to hear this. When it became clear that neither Gasparri nor del Val could win, the cardinals approached Ratti, thinking him a compromise candidate not identified with either faction. Cardinal Gaetano de Lai approached Ratti and was believed to have said: "We will vote for Your Eminence if Your Eminence will promise that you will not choose Cardinal Gasparri as your secretary of state". Ratti is said to have responded: "I hope and pray that among so highly deserving cardinals the Holy Spirit selects someone else. If I am chosen, it is indeed Cardinal Gasparri whom I will take to be my secretary of state".[21]

Ratti was elected pope on the conclave's fourteenth ballot on 6 February 1922 and took the name "Pius XI", explaining that Pius IX was the pope of his youth and Pius X had appointed him head of the Vatican Library. It was rumoured that immediately after the election, he decided to appoint Pietro Gasparri as his Cardinal Secretary of State.[21] When asked if he accepted his election, Ratti was said to have replied: "In spite of my unworthiness, of which I am deeply aware, I accept". He went on to say that his choice in papal name was because "Pius is a name of peace".[22]

It was said after the dean Cardinal Vincenzo Vannutelli asked if he assented to the election that Ratti paused in silence for two minutes according to Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier. The Hungarian cardinal János Csernoch later commented: "We made Cardinal Ratti pass through the fourteen stations of the Via Crucis and then we left him alone on Calvary".[23]

As Pius XI's first act as pope, he revived the traditional public blessing from the balcony, Urbi et Orbi ("to the city and to the world"), abandoned by his predecessors since the loss of Rome to the Italian state in 1870. This suggested his openness to a rapprochement with the government of Italy.[24] Less than a month later, considering that all four cardinals from the Western Hemisphere had been unable to participate in his election, he issued Cum proxime to allow the College of Cardinals to delay the start of a conclave for as long as eighteen days following the death of a pope.[25][26]

Public teaching: "The Peace of Christ in the Reign of Christ"

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Pius XI's first encyclical as pope was directly related to his aim of Christianising all aspects of increasingly secular societies. Ubi arcano, promulgated in December 1922, inaugurated the "Catholic Action" movement.

Similar goals were in evidence in two encyclicals of 1929 and 1930. Divini illius magistri ("That Divine Teacher") (1929) made clear the need for Christian over secular education.[27] Casti connubii ("Chaste Wedlock") (1930) praised Christian marriage and family life as the basis for any good society; it condemned artificial means of contraception, but acknowledged the unitive aspect of intercourse:

- ...[A]ny use whatsoever of matrimony exercised in such a way that the act is deliberately frustrated in its natural power to generate life is an offense against the law of God and of nature, and those who indulge in such are branded with the guilt of a grave sin.[28]

- ....Nor are those considered as acting against nature who in the married state use their right in the proper manner although on account of natural reasons either of time or of certain defects, new life cannot be brought forth. For in matrimony as well as in the use of the matrimonial rights there are also secondary ends, such as mutual aid, the cultivating of mutual love, and the quieting of concupiscence which husband and wife are not forbidden to consider so long as they are subordinated to the primary end and so long as the intrinsic nature of the act is preserved.[29]

Political teachings

In contrast to some of his predecessors in the nineteenth century who had favoured monarchy and dismissed democracy, Pius XI took a pragmatic approach toward the different forms of government. In his encyclical Dilectissima Nobis (1933), in which he addressed the situation of the Church in Republican Spain, he proclaimed,

Universally known is the fact that the Catholic Church is never bound to one form of government more than to another, provided the Divine rights of God and of Christian consciences are safe. She does not find any difficulty in adapting herself to various civil institutions, be they monarchic or republican, aristocratic or democratic.[30]

Social teachings

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic social teaching |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

|

Pius XI argued for a reconstruction of economic and political life on the basis of religious values. Quadragesimo anno (1931) was written to mark 'forty years' since Pope Leo XIII's (1878–1903) encyclical Rerum novarum, and restated that encyclical's warnings against both socialism and unrestrained capitalism, as enemies to human freedom and dignity. Pius XI instead envisioned an economy based on co-operation and solidarity.

In Quadragesimo anno, Pius XI stated that social and economic issues are vital to the Church not from a technical point of view but in terms of moral and ethical issues involved. Ethical considerations include the nature of private property[31] in terms of its functions for society and the development of the individual.[32] He defined fair wages and branded the exploitation both materially and spiritually by international capitalism.

Gender roles

Pius XI wrote that mothers should work primarily within the home, or in its immediate vicinity, and concentrate on household duties. He argued that every effort in society must be made for fathers to possess high enough wages, so that it never becomes a necessity within families for mothers to work. These forced dual income situations in which mothers work he describes as an "intolerable abuse".[33] Pius also attacks egalitarianist stances, describing modern attempts to liberate women as a "crime".[34] Pius XI states that attempts to liberate women from their husbands are a "false liberty and unnatural equality" and that the true emancipation of women "belongs to the noble office of a Christian woman and wife."[35]

Private property

The Church has a role in discussing the issues related to the social order. Social and economic issues are vital to her not from a technical point of view but in terms of the moral and ethical issues involved. Ethical considerations include the nature of private property.[31] Within the Catholic Church, several conflicting views had developed. Pope Pius XI declared private property essential for the development and freedom of the individual, and those who deny private property also deny personal freedom and development. Pius also said that private property has a social function and loses its morality, if it is not subordinated to the common good, and governments have a right to redistribution policies. In extreme cases, the Pope grants the state a right of expropriation of private property.[32]

Capital and labour

A related issue, said Pius, is the relation between capital and labour and the determination of fair wages.[36] Pius develops the following ethical mandate: The Church considers it a perversion of industrial society to have developed sharp opposite camps based on income. He welcomes all attempts to alleviate these differences. Three elements determine a fair wage: the worker's family, the economic condition of the enterprise, and the economy as a whole. The family has an innate right to development, but this is only possible within the framework of a functioning economy and a sound enterprise. Thus, Pius concludes that cooperation and not conflict is a necessary condition, given the mutual interdependence of the parties involved.[36]

Social order

Pius XI believed that industrialization results in less freedom at the individual and communal level because numerous free social entities get absorbed by larger ones. The society of individuals becomes the mass class-society. People are much more interdependent than in ancient times, and become egoistic or class-conscious in order to save some freedom for themselves. The pope demands more solidarity, especially between employers and employees, through new forms of cooperation and communication. Pius displays a negative view of capitalism, especially of the anonymous international finance markets.[37] He identifies certain dangers for small and medium-size enterprises, which have insufficient access to capital markets and are squeezed or destroyed by the larger ones. He warns that capitalist interests can become a danger for nations, which could be reduced to "chained slaves of individual interests"[38]

Pius XI was the first Pope to utilise the power of modern communications technology in evangelising the wider world. He established Vatican Radio in 1931, and he was the first Pope to broadcast on radio.

Internal Church affairs and ecumenism

In his management of the Church's internal affairs, Pius XI mostly continued the policies of his predecessor. Like Benedict XV, he emphasised spreading Catholicism in Africa and Asia and on the training of native clergy in those mission territories. He ordered every religious order to devote some of its personnel and resources to missionary work.

Pius XI continued the approach of Benedict XV on the issue of how to deal with the threat of modernism in Catholic theology. The Pope was thoroughly orthodox theologically and had no sympathy with modernist ideas that relativised fundamental Catholic teachings. He condemned modernism in his writings and addresses. However, his opposition to modernist theology was by no means a rejection of new scholarship within the Church, as long as it was developed within the framework of orthodoxy and compatible with the Church's teachings. Pius XI was interested in supporting serious scientific study within the Church, establishing the Pontifical Academy of the Sciences in 1936. In 1928 he formed the Gregorian Consortium of universities in Rome administered by the Society of Jesus, fostering closer collaboration between their Gregorian University, Biblical Institute, and Oriental Institute.[39][40]

Pius XI strongly encouraged devotion to the Sacred Heart in his encyclical Miserentissimus Redemptor (1928).

Pius XI was the first pope to directly address the Christian ecumenical movement. Like Benedict XV he was interested in achieving reunion with the Eastern Orthodox (failing that, he determined to give special attention to the Eastern Catholic churches). He also allowed the dialogue between Catholics and Anglicans which had been planned during Benedict XV's pontificate to take place at Mechelen. However, these enterprises were firmly aimed at actually reuniting with the Catholic Church other Christians who basically agreed with Catholic doctrine, bringing them back under papal authority. To the broad pan-Protestant ecumenical movement he took a more negative attitude.

He rejected, in his 1928 encyclical, Mortalium animos, the idea that Christian unity could be attained by establishing a broad federation of many bodies holding conflicting doctrines; rather, the Catholic Church was the true Church of Christ. "The union of Christians can only be promoted by promoting the return to the one true Church of Christ of those who are separated from it, for in the past they have unhappily left it." The pronouncement also prohibited Catholics from joining groups that encouraged interfaith discussion without distinction.[41]

The next year, the Vatican was successful in lobbying the Mussolini regime to require Catholic religious education in all schools, even those with a majority of Protestants or Jews. The Pope expressed his "great pleasure" with the move.[42]

In 1934, the Fascist government at the urging of the Vatican agreed to expand the probation on public gatherings of Protestants to include even private worship in homes.[43]

Beatifications and canonizations

Pius XI canonised a total of 34 saints throughout his pontificate including some prominent individuals such as: Bernadette Soubirous (1933), Therese of Lisieux (1925), John Vianney (1925), John Fisher (1935), Thomas More (1935) and John Bosco (1934). He also beatified a total of 464 individuals throughout his pontificate such as Pierre-René Rogue (1934) and Noël Pinot (1926).

Pius XI also named four individuals as Doctors of the Church:

- Peter Canisius (21 May 1925)

- John of the Cross (24 August 1926; naming him as "Doctor mysticus" or "Mystical Doctor")

- Roberto Bellarmino (17 September 1931)

- Albert the Great (16 December 1931; naming him as "Doctor universalis" or "Universal Doctor")

Consistories

Pius XI created a total of 76 cardinals in 17 consistories, including notable individuals such as August Hlond (1927), Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster (1929), Raffaele Rossi (1930), Elia Dalla Costa (1933), and Giuseppe Pizzardo (1937). One of those cardinals he elevated, on 16 December 1929, was his eventual successor, Eugenio Pacelli, who would become Pope Pius XII. Pius XI, in fact, believed that Pacelli would be his successor and dropped many hints he desired that. On one such occasion at a consistory for new cardinals on 13 December 1937, while posing with the new cardinals, Pius XI pointed to Pacelli and told them: "He'll make a good pope!"[23]

Pius XI also accepted the resignation of a cardinal from the cardinalate during his pontificate in 1927: the Jesuit Louis Billot.

The pope deviated from the usual practice of naming cardinals in collective consistories, instead, opting for smaller and more frequent consistories, with some of them being less than six months apart in length. He made the effort to increase the number of non-Italian cardinals, which had been lacking in his predecessor's consistories.

In 1923, Pius XI wanted to nominate Ricardo Sanz de Samper y Campuzano (majordomo in the Papal Household) to the College of Cardinals but was forced to abandon the idea when King Alfonso XIII of Spain insisted that the pope appoint cardinals from South America despite the fact that Sanz hailed from Colombia. Since Pius XI desired not appearing to have been influenced by politics, he named no South American cardinals in the December 1923 consistory. According to an article by the historian Monsignor Vicente Cárcel y Ortí, a 1928 letter saw Alfonso XIII ask that the pope restore Valencia as a cardinalitial see, hence, promote its archbishop Prudencio Melo y Alcalde to the cardinalate. However, Pius XI responded and said that he could not consider the promotion because Spain already had the habitual number of cardinals (set at four) with two of them fixed (Toledo and Seville) while the other two were variable appointments. While Pius XI recommended that Alfonso XIII wait for a future occasion, Pius XI never elevated the archbishop, leaving Valencia without a cardinal until 2007. In December 1935, the pope intended to name the Jesuit priest Pietro Tacchi Venturi to the cardinalate. However, he was forced to abandon the idea because he did not want to upset England since the promotion could have been perceived as a step towards supporting Fascism; the priest and Benito Mussolini were considered to be close.[44]

International relations

The pontificate of Pius XI coincided with the early aftermath of the First World War. The old European monarchies had been largely swept away and a new and precarious order formed across the continent. In the East, the Soviet Union arose. In Italy, the Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini took power, while in Germany, the fragile Weimar Republic collapsed with the Nazi seizure of power.[45] His reign was one of busy diplomatic activity for the Vatican. The Church made advances on several fronts in the 1920s, improving relations with France and, most spectacularly, settling the Roman question with Italy and gaining recognition of an independent Vatican state.

Pius XI's major diplomatic approach was to make concordats. He concluded eighteen such treaties during the course of his pontificate. However, wrote Peter Hebblethwaite, these concordats did not prove "durable or creditable" and "wholly failed in their aim of safeguarding the institutional rights of the Church" for "Europe was entering a period in which such agreements were regarded as mere scraps of paper".[46]

From 1933 to 1936 Pius wrote several protests against the Nazi regime, while his attitude to Mussolini's Italy changed dramatically in 1938, after Nazi racial policies were adopted in Italy.[45] Pius XI watched the rising tide of totalitarianism with alarm and delivered three papal encyclicals challenging the new creeds: against Italian Fascism Non abbiamo bisogno (1931; "We Do Not Need [to Acquaint You)"); against Nazism Mit brennender Sorge (1937; "With Deep Concern"), and against atheist Communism Divini redemptoris (1937; "Divine Redeemer"). He also challenged the extremist nationalism of the Action Française movement and anti-Semitism in the United States.[45]

Relations with France

France's republican government had long been anti-clerical, and much of the French catholic church anti-republican. The Law of Separation of Church and State in 1905 had expelled many religious orders from France, declared all Church buildings to be government property, and had led to the closure of most Church schools. Since that time Pope Benedict XV had sought a rapprochement, but it was not achieved until the reign of Pope Pius XI. In Maximam gravissimamque (1924), many areas of dispute were tacitly settled and a bearable coexistence made possible.[47]

In 1926, worried by the agnosticism of its leader Charles Maurras, Pius XI condemned the monarchist movement Action Française. The Pope also judged that it was folly for the French Church to continue to tie its fortunes to the unlikely dream of a monarchist restoration, and distrusted the movement's tendency to defend the Catholic religion in merely utilitarian and nationalistic terms.[48][49] Prior to this, Action Française had operated with the support of a great number of French lay Catholics, such as Jacques Maritain, as well as members of the clergy. Pius XI's decision was strongly criticized by Cardinal Billot who believed that the political activities of monarchist Catholics should not be censured by Rome.[50] He later resigned from his position as Cardinal, the only man to do so in the twentieth century, which is believed by some to have been the ultimate result of Pius XI's condemnation.[51] Pope Pius XII repealed the papal ban on the group in 1939, once again allowing Catholics to associate themselves with the movement.[52] However, despite Pius XII's actions to rehabilitate the group, Action Française ultimately never recovered to their former status.

Relations with Italy and the Lateran Treaties

Pius XI aimed to end the long breach between the papacy and the Italian government and to gain recognition once more of the sovereign independence of the Holy See. Most of the Papal States had been seized by the forces of King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy (1861–1878) in 1860 at the foundation of the modern unified Italian state, and the rest, including Rome, in 1870. The Papacy and the Italian Government had been at loggerheads ever since: the Popes had refused to recognise the Italian state's seizure of the Papal States, instead withdrawing to become prisoners in the Vatican, and the Italian government's policies had always been anti-clerical. Now Pius XI thought a compromise would be the best solution.

To bolster his own new regime, Benito Mussolini was also eager for an agreement. After years of negotiation, in 1929, the Pope supervised the signing of the Lateran Treaties with the Italian government. According to the terms of the treaty that was one of the agreed documents, Vatican City was given sovereignty as an independent nation in return for the Vatican relinquishing its claim to the former territories of the Papal States. Pius XI thus became a head of state (albeit the smallest state in the world), the first Pope who could be termed a head of state since the Papal States fell after the unification of Italy in the 19th century. The concordat that was another of the agreed documents of 1929 recognised Catholicism as the sole religion of the state (as it already was under Italian law, while other religions were tolerated), paid salaries to priests and bishops, gave civil recognition to church marriages (previously couples had to have a civil ceremony), and brought religious instruction into the public schools. In turn, the bishops swore allegiance to the Italian state, which had veto power over their selection.[53] The Church was not officially obligated its support the Fascist regime; the strong differences remained, but the seething hostility ended. Friction continued over the Catholic Action youth network, which Mussolini wanted to merge into his Fascist youth group.[54]

The third document in the agreement paid the Vatican 1750 million lira (about $100 million) for the seizures of church property since 1860. Pius XI invested the money in the stock markets and real estate. To manage these investments, the Pope appointed the lay-person Bernardino Nogara, who, through shrewd investing in stocks, gold, and futures markets, significantly increased the Catholic Church's financial holdings. The income largely paid for the upkeep of the expensive-to-maintain stock of historic buildings in the Vatican which until 1870 had been maintained through funds raised from the Papal States.

The Vatican's relationship with Mussolini's government deteriorated drastically after 1930 as Mussolini's totalitarian ambitions began to impinge more and more on the autonomy of the Church. For example, the Fascists tried to absorb the Church's youth groups. In response, Pius issued the encyclical Non abbiamo bisogno ("We Have No Need)" in 1931. It denounced the regime's persecution of the church in Italy and condemned "pagan worship of the State."[55] It also condemned Fascism's "revolution which snatches the young from the Church and from Jesus Christ, and which inculcates in its own young people hatred, violence and irreverence".[56]

From the earliest days of the Nazi takeover in Germany, the Vatican was taking diplomatic action to attempt to defend the Jews of Germany. In the spring of 1933, Pope Pius XI urged Mussolini to ask Hitler to restrain the anti-Semitic actions taking place in Germany.[57] Mussolini urged Pius to excommunicate Hitler, as he thought it would render him less powerful in Catholic Austria and reduce the danger to Italy and wider Europe. The Vatican refused to comply and thereafter Mussolini began to work with Hitler, adopting his anti-Semitic and race theories.[58] In 1936, with the Church in Germany facing clear persecution, Italy and Germany agreed to the Berlin-Rome Axis.[59]

Relations with Germany and Austria

The Nazis, like the Pope, were unalterably opposed to Communism. In the years leading up to the 1933 election, the German bishops opposed the NSDAP (Nazis) by proscribing German Catholics from joining and participating in the NSDAP (Nazi) party. This changed by the end of March after Cardinal Michael Von Fauhaber of Munich met with the Pope. One author claims that Pius expressed support for the regime soon after Hitler's rise to power, with the author asserting that he said, "I have changed my mind about Hitler, it is for the first time that such a government voice has been raised to denounce Bolshevism in such categorical terms, joining with the voice of the pope."[60]

A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the 1933 Nazi takeover in Germany.[61] In the dying days of the Weimar Republic, the newly appointed Chancellor Adolf Hitler moved quickly to eliminate political Catholicism. Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen was dispatched to Rome to negotiate a Reich concordat with the Holy See.[62] Ian Kershaw wrote that the Vatican was anxious to reach an agreement with the new government, despite "continuing molestation of Catholic clergy, and other outrages committed by Nazi radicals against the Church and its organisations".[63] Negotiations were conducted by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII (1939–1958). The Reichskonkordat was signed by Pacelli and by the German government in June 1933, and included guarantees of liberty for the Church, independence for Catholic organisations and youth groups, and religious teaching in schools.[64] The treaty was an extension of existing concordats already signed with Prussia and Bavaria, but wrote Hebblethwaite, it seemed "more like a surrender than anything else: it involved the suicide of the Centre Party... ".[46]

"The agreement", wrote William Shirer, "was hardly put to paper before it was being broken by the Nazi Government". On 25 July, the Nazis promulgated their sterilization law, an offensive policy in the eyes of the Catholic Church. Five days later, moves began to dissolve the Catholic Youth League. Clergy, nuns and lay leaders began to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality".[65]

In February 1936, Hitler sent Pius a telegram congratulating the Pope on the anniversary of his coronation, but he responded with criticisms of what was happening in Germany, so much so that Neurath, the foreign secretary, wanted to suppress it, but Pius insisted it be forwarded.[66]

Austria

The pope supported the Christian Socialists in Austria, a country with a majority Catholic population but a powerful secular element. He especially supported the regime of Engelbert Dollfuss (1932–1934), who wanted to remold society based on papal encyclicals. Dollfuss suppressed the anti-clerical elements and the socialists but was assassinated by the Austrian Nazis in 1934. His successor Kurt von Schuschnigg (1934–1938) was also pro-Catholic and received Vatican support.[67] The Anschluss saw the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in early 1938.[68] Austria was overwhelmingly Catholic.[69]

At the direction of Cardinal Innitzer, the churches of Vienna pealed their bells and flew swastikas for Hitler's arrival in the city on 14 March.[70] However, wrote Mark Mazower, such gestures of accommodation were "not enough to assuage the Austrian Nazi radicals, foremost among them the young Gauleiter Globocnik".[71] Globocnik launched a crusade against the Church, and the Nazis confiscated property, closed Catholic organisations and sent many priests to Dachau.[71] Anger at the treatment of the Church in Austria grew quickly and October 1938, wrote Mazower, saw the "very first act of overt mass resistance to the new regime", when a rally of thousands left Mass in Vienna chanting "Christ is our Fuehrer", before being dispersed by police.[72] A Nazi mob ransacked Cardinal Innitzer's residence, after he had denounced Nazi persecution of the Church.[69] The American National Catholic Welfare Conference wrote that Pope Pius, "again protested against the violence of the Nazis, in language recalling Nero and Judas the Betrayer, comparing Hitler with Julian the Apostate."[73]

Mit brennender Sorge

The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity, interfered with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies.[74] By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI issued the Mit brennender Sorge encyclical – accusing the Nazi Government of violations of the 1933 Concordat, and further that it was sowing the "tares of suspicion, discord, hatred, calumny, of secret and open fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church". The Pope noted on the horizon the "threatening storm clouds" of religious wars of extermination over Germany.[65]

Copies had to be smuggled into Germany so they could be read from their pulpits.[75] The encyclical, the only one ever written in German, was addressed to German bishops and was read in all parishes of Germany. The actual writing of the text is credited to Munich Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber and to the Cardinal Secretary of State, Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII.[76]

There was no advance announcement of the encyclical, and its distribution was kept secret in an attempt to ensure the unhindered public reading of its contents in all the Catholic churches of Germany. This encyclical condemned particularly the paganism of Nazism, the myth of race and blood, and fallacies in the Nazi conception of God:

Whoever exalts race, or the people, or the State, or a particular form of State, or the depositories of power, or any other fundamental value of the human community – however necessary and honorable be their function in worldly things – whoever raises these notions above their standard value and divinizes them to an idolatrous level, distorts and perverts an order of the world planned and created by God; he is far from the true faith in God and from the concept of life which that faith upholds.[77]

The Nazis responded with an intensification of their campaign against the churches, beginning around April.[78] There were mass arrests of clergy and church presses were expropriated.[79]

Response of the press and governments

While numerous German Catholics, who participated in the secret printing and distribution of the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge, went to jail and concentration camps, the Western democracies remained silent, which Pius XI labeled bitterly a "conspiracy of silence".[80][81] As the extreme nature of Nazi racial anti-Semitism became obvious, and as Mussolini in the late 1930s began imitating Hitler's anti-Jewish race laws in Italy, Pius XI continued to make his position clear, both in Mit brennender Sorge and after Fascist Italy's Manifesto of Race was published, in a public address in the Vatican to Belgian pilgrims in 1938: "Mark well that in the Catholic Mass, Abraham is our Patriarch and forefather. Anti-Semitism is incompatible with the lofty thought which that fact expresses. It is a movement with which we Christians can have nothing to do. No, no, I say to you it is impossible for a Christian to take part in anti-Semitism. It is inadmissible. Through Christ and in Christ we are the spiritual progeny of Abraham. Spiritually, we [Christians] are all Semites"[82] These comments were reported by neither Osservatore Romano nor Vatican Radio.[83] They were reported in Belgium on 14 September 1938 issue of La Libre Belgique[84] and on 17 September 1938 issue of French Catholic daily La Croix.[85] They were then published worldwide but had little resonance at the time in the secular media.[80] The "conspiracy of silence" included not only the silence of secular powers against the horrors of Nazism but also their silence on the persecution of the Church in Mexico, the Soviet Union and Spain. Despite these public comments, Pius was reported to have suggested privately that the Church's problems in those three countries were "reinforced by the anti-Christian spirit of Judaism".[86]

Kristallnacht

When the then-newly installed Nazi government began to instigate its program of anti-Semitism in 1933, Pius XI ordered the papal nuncio in Berlin, Cesare Orsenigo, to "look into whether and how it may be possible to become involved" in their aid. Orsenigo proved a poor instrument in this regard, concerned more with the anti-church policies of the Nazis and how these might affect German Catholics, than with taking action to help German Jews.[87]

On 11 November 1938, following Kristallnacht, Pius XI joined Western leaders in condemning the pogrom. In response, the Nazis organised mass demonstrations against Catholics and Jews in Munich, and the Bavarian Gauleiter Adolf Wagner declared before 5,000 protesters: "Every utterance the Pope makes in Rome is an incitement of the Jews throughout the world to agitate against Germany".[88] On 21 November, in an address to the world's Catholics, the Pope rejected the Nazi claim of racial superiority, and insisted instead that there was only a single human race. Robert Ley, the Nazi Minister of Labour declared the following day in Vienna: "No compassion will be tolerated for the Jews. We deny the Pope's statement that there is but one human race. The Jews are parasites." Catholic leaders, including Cardinal Schuster of Milan, Cardinal van Roey in Belgium and Cardinal Verdier in Paris, backed the Pope's strong condemnation of Kristallnacht.[89]

Relations with East Asia

Under Pius XI, papal relations with East Asia were marked by the rise of the Japanese Empire to prominence, as well as the unification of China under Chiang Kai-shek. In 1922 he established the position of Apostolic Delegate to China, and the first person in that capacity was Celso Benigno Luigi Costantini.[90] On 1 August 1928, the Pope addressed a message of support for the political unification of China. Following the Japanese invasion of North China in 1931 and the creation of Manchukuo, the Holy See recognized the new state. On 10 September 1938, the Pope held a reception at Castel Gandolfo for an official delegation from Manchukuo, headed by Manchukuoan Minister of Foreign Affairs Han Yun.[91]

Involvement with American efforts

Mother Katharine Drexel, who founded the American order of Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People, corresponded with Pius XI, as she had with his papal predecessors. (In 1887, Pope Leo XIII had encouraged Katharine Drexel—then a young Philadelphia socialite— to do missionary work with America's disadvantaged people of color). In the early 1930s, Mother Drexel wrote Pius XI asking him to bless a publicity campaign to acquaint white Catholics with the needs of these disadvantaged races among them. An emissary had shown him photos of Xavier University, New Orleans, LA, which Mother Drexel had established to educate African-Americans at the highest level in the USA. Pius XI replied promptly, sending his blessing and encouragement. Upon his return, the emissary told Mother Katharine that the Pope said he had read the novel Uncle Tom's Cabin as a boy, and it had ignited his lifelong concern for the American Negro.[92]

Brazil

In 1930, Pius XI declared the Immaculate Conception under the title of Our Lady of Aparecida as the Queen and Patroness of Brazil.[93]

Persecution of Christians

Pius XI was faced with unprecedented persecution of the Catholic Church in Mexico and Spain and with the persecution of all Christians especially the Eastern Catholic Churches in the Soviet Union. He called this the "terrible triangle".[94]

Soviet Union

Worried by the persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union, Pius XI mandated Berlin nuncio Eugenio Pacelli to work secretly on diplomatic arrangements between the Vatican and the Soviet Union. Pacelli negotiated food shipments for Russia and met with Soviet representatives, including Foreign Minister Georgi Chicherin, who rejected any kind of religious education and the ordination of priests and bishops but offered agreements without the points vital to the Vatican.[95] Despite Vatican pessimism and a lack of visible progress, Pacelli continued the secret negotiations, until Pius XI ordered them discontinued in 1927 because they generated no results and would be dangerous to the Church if made public.

The "harsh persecution short of total annihilation of the clergy, monks, and nuns and other people associated with the Church",[96] continued well into the 1930s. In addition to executing and exiling many clerics, monks and laymen, the confiscating of Church implements "for victims of famine" and the closing of churches were common.[97] Yet according to an official report based on the census of 1936, some 55% of Soviet citizens identified themselves openly as religious.[97]

Mexico

During the pontificate of Pius XI, the Catholic Church was subjected to extreme persecutions in Mexico, which resulted in the death of over 5,000 priests, bishops and followers.[98] In the state of Tabasco the Church was in effect outlawed altogether. In his encyclical Iniquis afflictisque[99] from 18 November 1926, Pope Pius protested against the slaughter and persecution. The United States intervened in 1929 and moderated an agreement.[98] The persecutions resumed in 1931. Pius XI condemned the Mexican government again in his 1932 encyclical Acerba animi. Problems continued with reduced hostilities until 1940, when in the new pontificate of Pope Pius XII President Manuel Ávila Camacho returned the Mexican churches to the Catholic Church.[98]

There were 4,500 Mexican priests serving the Mexican people before the rebellion, in 1934, over 90% of them suffered persecution as only 334 priests were licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people. Excluding foreign religious, over 4,100 Mexican priests were eliminated by emigration, expulsion and assassination.[100][101] By 1935, 17 Mexican states were left with no priests at all.[102]

Spain

The Republican government which came to power in Spain in 1931 was strongly anti-clerical, secularising education, prohibiting religious education in the schools, and expelling the Jesuits from the country. On Pentecost 1932, Pope Pius XI protested against these measures and demanded restitution.

Syro-Malankara Catholic Church

Pius XI accepted the Reunion Movement of Mar Ivanios along with four other members of the Malankara Orthodox Church in 1930. As a result of the Reunion Movement, the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church is in full communion with the Bishop of Rome and the Catholic Church.

Condemnation of racism

The Fascist government in Italy abstained from copying Germany's racial and anti-Semitic laws and regulations until 1938 when Italy introduced anti-Semitic legislation. The Pope publicly asked Italy to abstain from adopting a demeaning racist legislation, stating that the term "race" is divisive but may be appropriate to differentiate animals.[103] The Catholic view would refer to "the unity of human society", which includes as many differences as music includes intonations. Italy, a civilized country, should not ape the barbarian German legislation, he said.[104] In the same speech, he criticized the Italian government for attacking Catholic Action and even the papacy itself.

In April 1938, at the request of Pius XI, the Sacred Congregation of seminaries and universities developed a syllabus condemning racist theories. Its publication was postponed.[105]

In one historian's view:

By the time of his death ... Pius XI had managed to orchestrate a swelling chorus of Church protests against the racial legislation and the ties that bound Italy to Germany. He had single-mindedly continued to denounce the evils of the Nazi regime at every possible opportunity and feared above all else the re-opening of the rift between Church and State in his beloved Italy. He had, however, few tangible successes. There had been little improvement in the position of the Church in Germany and there was growing hostility to the Church in Italy on the part of the fascist regime. Almost the only positive result of the last years of his pontificate was a closer relationship with the liberal democracies and yet, even this was seen by many as representing a highly partisan stance on the part of the Pope.[106]

Humani generis unitas

Pius XI planned an encyclical Humani generis unitas (The Unity of the Human Race) to denounce racism in the US, Europe and elsewhere, as well as antisemitism, colonialism and violent German nationalism. He died without issuing it.[107]

Pius XI's successor, Pius XII, who was not aware of the text before the death of his predecessor,[108] chose not to publish it. His first encyclical Summi Pontificatus ("On the Supreme Pontificate", 12 October 1939), published after the beginning of World War II, bore the title On the Unity of Human Society and used many of the arguments of the document drafted for Pius XI, while avoiding its negative characterizations of the Jewish people.

To denounce racism and anti-Semitism, Pius XI sought out the American Jesuit journalist John LaFarge and summoned him to Castel Gandolfo on 25 June 1938. The pope told the Jesuit that he planned to write an encyclical denouncing racism, and asked LaFarge to help write it while swearing him to strict silence. LaFarge took up this task in secret in Paris, but the Jesuit Superior-General Wlodimir Ledóchowski promised the pope and LaFarge that he would facilitate the encyclical's production. This proved to be a hindrance since Ledóchowski was privately an anti-Semite and conspired to block Lafarge's efforts whenever and wherever possible. In late September 1938, the Jesuit had finished his work and returned to Rome, where Ledóchowski welcomed him and promised to deliver the work to the pope immediately. LaFarge was directed to return to the United States, while Ledóchowski concealed the draft from the pope, who remained wholly unaware of what had transpired.[109]

But in the fall of 1938, LaFarge had realized the Pope still had not received the draft and sent a letter to Pius XI where he implied that Ledóchowski had the document in his possession. Pius XI demanded that the draft be delivered to him, but did not receive it until 21 January 1939 with a note from Ledóchowski, who warned that the draft's language was excessive and advised caution. Pius XI planned to issue the encyclical following his meeting with bishops on 11 February, but died before both the meeting and encyclical's promulgation could take place.[109]

Personality

Pius XI was seen as a blunt-spoken and no-nonsense man, qualities he shared with Pope Pius X. He was passionate about science and was fascinated with the power of radio, which would soon result in the founding and inauguration of Vatican Radio. He was intrigued by new forms of technology that he employed during his pontificate. He was also known for a rare smile.

Pius XI was known[110] to have a temper at times[110] and was someone who had a keen sense of knowledge and dignity of the office he held.[110] He insisted that he eat alone with no one around him[110] and would not allow his assistants or any other priests or clergy to dine with him.[110] He would frequently meet with political figures but would always greet them seated. He insisted that when his brother and sister wanted to see him, they had to refer to him as "Your Holiness"[110] and book an appointment.[110]

Pius XI was also a very demanding individual, certainly one of the stricter pontiffs at that time. He held very high standards and did not tolerate any sort of behaviour that was not up to that standard.[110] In regard to Angelo Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII, a diplomatic blunder in Bulgaria, where Roncalli was stationed, led Pius XI to make Roncalli kneel for 45 minutes as a punishment.[111][110] However when in due course Pius learned that Roncalli had made the error in circumstances for which he could not fairly be considered culpable, he apologized to him. Aware of the implied impropriety of a Supreme Pontiff's going back on a reprimand in a matter concerning Catholic faith and morals,[112] but also deeply conscious that on a human level he had failed to keep his temper in check, he made his apology "as Achille Ratti" and in doing so stretched out his hand in friendship to Monsignor Roncalli.[113]

| Papal styles of Pope Pius XI | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | None |

Death and burial

Pius XI had been ill for some time when, on 25 November 1938, he suffered two heart attacks within several hours. He had serious breathing problems and could not leave his apartment.[114] He gave his last major pontifical address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, which he had founded, speaking without a prepared text on the relation between science and the Catholic religion.[115] Medical specialists reported that heart insufficiency combined with bronchial attacks had hopelessly complicated his already poor prospects.

Pius XI died at 5:31 a.m. (Rome time) of a third heart attack on 10 February 1939, at the age of 81. His last words to those near him at the time of his death were spoken with clarity and firmness: "My soul parts from you all in peace."[116] Some believe he was murdered, based on the fact that his primary physician was Dr. Francesco Petacci, father of Claretta Petacci, Mussolini's mistress.[117][118][119][120][121] Cardinal Eugène Tisserant wrote in his diary that the pope had been murdered, which was a statement that Carlo Confalonieri later strongly denied.[109]

The Pope's last audible words were reported to have been: "peace, peace" as he died. Those at his bedside at 4:00 am realized that the pontiff's end was near, at which stage the sacrist was summoned to administer the final sacrament to the pope 11 minutes before the pope's death. The pontiff's confessor Cardinal Lorenzo Lauri arrived a few seconds too late. After his final words, the pope's lips moved slowly with Dr. Rocchi saying it was occasionally possible to discern that the pope was making an effort to recite a Latin prayer.[122] About half a minute before his death, Pius XI raised his right hand weakly and tried making the sign of the Cross to impart his last blessing to those gathered at his bedside. One of the last things the pontiff was reported to have said was "We still had so many things to do" and died among a low murmur of psalms recited from those present. Upon his death, his face was covered by a white veil. Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, in accordance with his duties as Camerlengo lifted the veil and gently struck the pope's forehead three times reciting his Christian name (Achille) and pausing for an answer to confirm truly if the pope had died, before turning to those present and in Latin saying: "Truly the pope is dead."[122]

Upon Pius XI's death, the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Lang paid tribute to the pope's efforts for world peace, calling him a man of "sincere piety" who bore his duties with exceptional "dignity and courage". Others who sent messages of condolences were Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, the former visiting the Vatican to pay his respects to the deceased pontiff. Flags were flown half-staff in Rome, Paris, and Berlin.[122]

Pius XI's body was placed in a wooden coffin, placed in a bronze casket, which was then placed in a lead casket.[123] The casket was designed by Antonio Berti.[124] Following the funeral, Pius XI was buried in the crypt of St. Peter's Basilica on 14 February 1939, in the Chapel of Saint Sebastian, close to the tomb of Saint Peter.[125] His tomb was modified in 1944 to be more ornate.[126]

Legacies

Pius XI is remembered as the pope who reigned between the two great wars of the 20th century. The onetime librarian also reorganized the Vatican archives. Nevertheless, Pius XI was hardly a withdrawn and bookish figure. He was also a well-known mountain climber with many peaks in the Alps named after him, he having been the first to scale them.[127]

A Chilean glacier bears Pius XI's name.[128] In 1940, Bishop T. B. Pearson founded the Achille Ratti Climbing Club, based in the United Kingdom and named for Pius XI.[129]

Pius XI also refounded the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1936, with the aim of turning it into the "scientific senate" of the Church. Hostile to any form of ethnic or religious discrimination, he appointed over eighty academicians from a variety of countries, backgrounds and areas of research.[130] In his honour, John XXIII established the Pius XI Medal that the Council of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences awards to a young scientist under the age of 45 who has distinguished himself or herself at the international level.[131]

The Syro-Malankara Catholic Church founded a school in his name in Kattanam, Mavelikkara, Kerala, India.[132]

Pius XI High School in Milwaukee Wisconsin, founded in 1929, is named in honor of the pontiff.

See also

- Cardinals created by Pius XI

- List of encyclicals of Pope Pius XI

- Pope Pius XI and Judaism

Citations

- "Ratti Ambrogio Damiano Achille". Araldicavaticana.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- Metzler, Josef (1 April 1993). "The legacy of Pius XI". International Bulletin of Missionary Research. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- "Studiorum ducem". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- "STUDIORUM DUCEM (On St. Thomas Aquinas)[English translation]". EWTN. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Rev. William P. Saunders (13 February 2014). "Does the church possess the actual bones of St. Peter?". Catholic Straight Answers. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- "Vatican displays Saint Peter's bones for the first time". The Guardian. 24 November 2013. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Jacob Neusner (9 July 2004). Christianity, Judaism and Other Greco-Roman Cults, Part 2: Early Christianity. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-59244-740-4. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018.

- D'Orazi, 15–19.

- "POPE'S BROTHER DIES.; Count Fermo Ratti, Ill Two Days, Succumbs Suddenly". The New York Times. 1 January 1930. p. 29. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- D'Orazi, 14–24.

- D'Orazi, 27.

- Schmidlin III, 306.

- Schmidlin III, 307.

- Fontenelle, 34–44.

- AAS 1921, 566.

- Stehle, 25.

- Schmidlin IV, 15.

- Stehle, 26.

- Fontenelle, 40.

- Fontenelle, 44.

- Kertzer 2014.

- Luca Frigerio (3 February 2022). "Achille Ratti: cento anni fa la sua elezione a Papa". Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Milan. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- John-Peter Pham (2004). Heirs of the Fisherman: Behind the Scenes of Papal Death and Succession. ISBN 9780195346350.

- Fontenelle, 44–56.

- Trythall, Marisa Patrulli (2010). "Pius XI and American Pragmatism". In Gallagher, Charles R.; Kertzer, David I.; Melloni, Alberto (eds.). Pius XI and America: Proceedings of the Brown University Conference. Lit Verlag. p. 28. ISBN 9783643901460. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018.

- Pope Pius XI (1 March 1922). "Cum proxime" (in Italian). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Divini Illius Magistri (December 31, 1929) | PIUS XI". w2.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015.

- Casti Connubii Archived 18 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Section 56.

- Casti Connubii Archived 18 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Section 59.

- Pius XI (3 June 1933). "Vatican website information re pontificate and policies of Pius XI". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 5 October 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- Quadragesimo anno, 44–52.

- Quadragesimo anno, 114–115.

- Quadragesimo Anno, 71.

- Casti Connubii, 74."

- Casti Connubii, 75.

- Quadragesimo anno, 63–75.

- Quadragesimo anno, 99 ff.

- Quadragesimo anno, 109.

- "Storia del P.I.O." Orientale (in Italian). Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Pope Pius XI (30 September 1928). "Motu Proprio Quod Maxime". w2.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Pope Pius XI, Mortalium animos, 6 January 1928.

- Kertzer 2014, 3329.

- Kertzer 2014, 3323.

- Salvador Miranda. "Pius XI (1922-1939)". The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online: Pius XI; web Apr. 2013

- Peter Hebblethwaite; Paul VI, the First Modern Pope; Harper Collins Religious; 1993; p.118

- Kenneth Scott Latourette, Christianity in a Revolutionary Age: A History of Christianity in the 19th and 20th Century: Vol 4 The 20th Century In Europe (1961) pp 129–53

- Latourette, Christianity in a Revolutionary Age pp 37–38

- Eugen Weber (1962). Action Française: Royalism and Reaction in Twentieth-Century France. Stanford U.P. p. 249. ISBN 9780804701341.

- TIME Magazine. Billot v. Pope October 3, 1927

- "French Cardinal Resigns Purple to Enter Monastery" (PDF). The New York Times. 16 October 1927. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Friedländer, Saul. Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Persecution, 1997, New York: HarperCollins, p. 223

- Cyprian Blamires (2006). World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 120. ISBN 9781576079409. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016.

- Kenneth Scott Latourette, Christianity in a Revolutionary Age A History of Christianity in the 19th and 20th Century: Vol 4 The 20th Century In Europe (1961) pp 32–35, 153, 156, 371

- Eamon Duffy (2002). Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes; Second Edition. Yale University Press. p. 340. ISBN 9780300091656. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online: Fascism – identification with Christianity; web Apr. 2013

- Paul O'Shea; A Cross Too Heavy; Rosenberg Publishing; p. 230 ISBN 9781877058714

- Frank J. Coppa, The papacy, the Jews, and the Holocaust, Catholic University of America Press, 2006, p. 166-167, ISBN 0813214491.

- Peter Hebblethwaite; Paul VI, the First Modern Pope; Harper Collins Religious; 1993; p.129

- Kertzer 2014, 3359.

- Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; W.W. Norton & Company; London; p.332

- Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; W.W. Norton & Company; London; p.290

- Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; WW Norton & Company; London; p.295

- Latourette, Christianity in a Revolutionary Age: A History of Christianity in the 19th and 20th Century: Vol 4 The 20th Century in Europe (1961) pp 176–88

- William L. Shirer; The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; Secker & Warburg; London; 1960; p234-5

- "The papacy, the Jews, and the Holocaust", Frank J. Coppa, p. 160, Catholic University Press of America, 2006, ISBN 0813214491

- Latourette, Christianity in a Revolutionary Age A History of Christianity in the 19th and 20th Century: Vol 4 The 20th Century In Europe (1961) pp 188–91

- William L. Shirer; The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; Secker & Warburg; London; 1960; pp. 325–329

- William L. Shirer; The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; Secker & Warburg; London; 1960; pp. 349–350.

- Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; W.W. Norton & Co; London; p. 413

- Mark Mazower; Hitler's Empire – Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe; Penguin; 2008; ISBN 978-0-713-99681-4; pp.51–52

- Mark Mazower; Hitler's Empire – Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe; Penguin; 2008; ISBN 978-0-713-99681-4; p.52

- The Nazi War Against the Catholic Church; National Catholic Welfare Conference; Washington D.C.; 1942; pp.29–30

- Theodore S. Hamerow; On the Road to the Wolf's Lair – German Resistance to Hitler; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1997; ISBN 0-674-63680-5; p. 136

- Manners 2002, p. 374.

- August Franzen, Remigius Bäumer Papstgeschichte Herder Freiburg, 1988, p. 394.

- Mit brennender Sorge, 8.

- Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; WW Norton & Company; London; p.381-382

- Joachim Fest; Plotting Hitler's Death: The German Resistance to Hitler 1933–1945; Weidenfeld & Nicolson; London; p.374

- Franzen, 395.

- Encyclical Divini Redemptoris, § 18 (AAS 29 [1937], 74). 1937. Libreria Editrice Vaticana (English translation Archived 9 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine)

- Marchione 1997, p. 53.

- John Connelly, Nazi Racism & the Church: How Converts Showed the Way to Resist Archived 21 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Commonweal, 24 February 2012

- Giovanni Miccoli, " Les Dilemmes et les silences de Pie XII: Vatican, Seconde Guerre mondiale et Shoah », Éditions Complexe, 2005, ISBN 9782870279373, p. 401

- La Croix, 17 September 1938, page 1 Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Gallica, accessed 12 November 2012

- Geert, Mak (2004). In Europe:Travels through the 20th century. p. 295.

- Paul O'Shea; A Cross Too Heavy; Rosenberg Publishing; p. 232 ISBN 9781877058714

- Martin Gilbert; Kristallnacht – Prelude to Disaster; HarperPress; 2006; p.143

- Martin Gilbert; Kristallnacht – Prelude to Disaster; HarperPress; 2006; p.172

- "Celso Costantini's Contribution to the Localization and Inculturation of the Church in China". Hsstudyc.org.hk. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- "Chen Fang-Chung, "Lou Tseng-Tsiang, A Lover of His Church and of His Country"". Hsstudyc.org.hk. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- The Golden Door: The Life of Katharine Drexel, by Katherine Burton (P. J. Kenedy & Sons, New York, 1957, p. 261)

- Rosales, Luis; Olivera, Daniel (2013). Francis: A Pope for our Time: The Definitive Biography. Humanix Books. p. 96. ISBN 978-1630060022. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016.

- Fontenelle, 164.

- Hansjakob Stehle, Die Ostpolitik des Vatikans, Piper, München, 1975, pp. 139–141.

- Riasanovsky 1963, p. 617.

- Riasanovsky 1963, p. 634.

- Franzen, 398.

- Pope Pius XI (18 November 1926). "Iniquis afflictisque". Archived from the original on 8 November 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899 Archived 19 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine p. 33 (2003 Brassey's) ISBN 1-57488-452-2.

- Van Hove, Brian Blood-Drenched Altars Archived 15 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine Faith & Reason 1994.

- Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People Archived 17 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine p. 393 (1993 W. W. Norton & Company) ISBN 0-393-31066-3.

- Confalioneri, 351.

- Confalioneri, 352.

- Hubert Wolf, Kenneth Kronenberg, Pope and Devil: The Vatican's Archives and the Third Reich (2010), p. 283

- Peter C. Kent, "A Tale of Two Popes: Pius XI, Pius XII and the Rome-Berlin Axis," Journal of Contemporary History (1988) 23#4 pp 589–608 in JSTOR Archived 7 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- The draft text was published in 1995 by Georges Passelecq and Berard Suchecky as L'Encyclique Cachée De Pie XI. La Découverte, Paris 1995.

- Letter of Father Maher to Father La Farge, 16 March 1939.

- Peter Eisner (15 April 2013). "Pope Pius XI's Last Crusade". Huffington Post. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "'Pope And Mussolini' Tells The 'Secret History' Of Fascism and the Church : NPR". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- Yves Chiron, Pius XI, Perrin, 2004, 418 pp.

- Hebblethwaite, Peter (1994), John XXIII, Pope of the Council (rev ed.), Glasgow: Harper Collins

- Elliott, L, 1974, I will be called John – A Biography of Pope John XXIII, London, Collins.

- Confalonieri, 356.

- Confalonieri, 358.

- Confalonieri, 373.

- Frank J. Coppa, Pope Pius XII: From the Diplomacy of Impartiality to the Silence of the Holocaust, Journal of Church and State, 23 December 2011.

- Saul Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews: I. The Years of Persecution, 1933–1939, New York: Harper-Collins, 1997, p. 277.

- Harry J. Cargas, Holocaust scholars write to the Vatican, 1998, ISBN 0-313-30487-4.

- John Cornwell, Hitler's Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII. Viking, 1999. ISBN 978-0-670-88693-7, p.204

- Newsweek, Volume 79, 1972, p. 238.

- "DEATH OF POPE PIUS XI. AFTER REIGN OF 17 YEARS Last Words Typified His Life". 11 February 1939. p. 1 – via Trove.

- Reardon, Wendy J. (2010). The Deaths of the Popes: Comprehensive Accounts, Including Funerals, Burial Places and Epitaphs. McFarland. p. 240. ISBN 9780786461165.

- Spike, John T. (19 February 2007). "The Marinelli Foundry Of Florence - An Overview".

- "PIUS ENTOMBED BENEATH ALTAR OF ST. PETER'S". San Pedro News Pilot. Vol. 11, no. 293. 14 February 1939.

- "Given the high quality of the monumental reliefs that adorn the ramp of the restored entry of the Vatican Museum, executed by the Fonderia Marinelli, the Vatican also commissioned the construction of a new bronze tomb of Pope Pius XI". Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- The New York Times. Tuesday, 7 February 1922, Page 1 (continued on page 3) Archived 6 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 3059 words.

- McIlvain, Josh (2009). Fodor's Patagonia. Fodor's Travel. pp. 45–6. ISBN 978-1-4000-0684-7. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016.

- "About the ARCC". Achille Ratti Climbing Club. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Pius XI". Casinapioiv.va. Archived from the original on 13 July 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- "John XXIII, Blessed". Casinapioiv.va. Archived from the original on 13 July 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- "Sametham - Kerala School Data Bank". SAMETHAM - Kerala School Bank.

Notes

- English: Ambrose Damian Achilles Ratti

Sources and further reading

- Browne-Olf, Lillian. Their Name Is Pius (1941) pp 305–59 online

- Confalonieri, Carlo (1975). Pius XI – A Close Up. (1975). Altadena, California: The Benzinger Sisters Press.

- Eisner, Peter, (2013), The Pope's Last Crusade: How an American Jesuit Helped Pope Pius XI's Campaign to Stop Hitler, New York, New York: HarperCollins |ISBN 978-0-06-204914-8

- Fattorini, Emma (2011), Hitler, Mussolini and the Vatican: Pope Pius XI and the Speech that was Never Made, Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity Press

- Kertzer, David I. (2014). The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198716167.

- Manners, John (2002), The Oxford History of Christianity, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-280336-8

- Marchione, Margherita (1997), Yours Is a Precious Witness: Memoirs of Jews and Catholics in Wartime Italy, Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, ISBN 978-0-8091-0485-7

- Morgan, Thomas B. (1937) A Reporter at the Papal Court – A Narrative of the Reign of Pope Pius XI. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Wolf, Hubert (2010), Pope and Devil: The Vatican Archives and the Third Reich. Trans. Kenneth Kronenberg, Cambridge, MA and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Other languages

- Ceci, Lucia (2013), L'interesse superiore. Il Vaticano e l'Italia di Mussolini, Laterza, Roma-Bari

- Chiron, Yves (2004), Pie XI (1857–1939), Perrin, Paris, ISBN 2-262-01846-4.

- D'Orazi, Lucio (1989), Il Coraggio Della Verita Vita do Pio XI, Edizioni logos, Roma

- Ceci, Lucia (2010), Il papa non-deve parlare. Chiesa, fascismo e guerra di Etiopia", Laterza, Roma-Bari

- Fontenelle, Mrg R (1939), Seine Heiligkeit Pius XI. Alsactia, France

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (1963), A History of Russia, New York: Oxford University Press

- Schmidlin, Josef (1922–1939), Papstgeschichte, Vol I-IV, Köstel-Pusztet München

- Peter Rohrbacher (2012), "Völkerkunde und Afrikanistik für den Papst". Missionsexperten und der Vatikan 1922–1939 in: Römische Historische Mitteilungen 54: 583–610

External links

- The Life of Pope Pius XI, also about his encyclical Quadragesimo anno

- Vatican Website for Pope Pius XI

- Pius XI Medal of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences

- Pius XI biography and his addresses to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences

- Catholic Forum Biography

- Vatican Museum Biography

- Pius XI and the mystery of the disappeared encyclical on YouTube

- Pope Benedict XVI opens the Archives for the pontificate (1922–1939) of Pope Pius XI – VATICAN CITY, 2 July 2006 "...researchers will be able to consult all the documents of the period kept in the different series of archives of the Holy See, primarily in the Vatican Secret Archives and the Archive of the Second Section of the Secretariat of State...."

- Achille Ratti climbing club

- Pathe News archive footage of Pius XI

- Newspaper clippings about Pope Pius XI in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

.jpg.webp)