American Beauty (1999 film)

American Beauty is a 1999 American black comedy-drama film written by Alan Ball and directed by Sam Mendes in his directorial debut. Kevin Spacey stars as Lester Burnham, an advertising executive who has a midlife crisis when he becomes infatuated with his teenage daughter's best friend, played by Mena Suvari. Annette Bening stars as Lester's materialistic wife, Carolyn, and Thora Birch plays their insecure daughter, Jane. Wes Bentley, Chris Cooper, and Allison Janney co-star. Academics have described the film as satirizing how beauty and personal satisfaction are perceived by the American middle class; further analysis has focused on the film's explorations of romantic and paternal love, sexuality, materialism, self-liberation, and redemption.

| American Beauty | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sam Mendes |

| Written by | Alan Ball |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Conrad L. Hall |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Thomas Newman |

Production company | Jinks/Cohen Company |

| Distributed by | DreamWorks Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 122 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million[2] |

| Box office | $356.3 million[2] |

Released in North America on September 17, 1999, American Beauty received widespread critical and popular acclaim; it was the second-best-reviewed American film of the year behind Being John Malkovich and grossed over $350 million worldwide against its $15-million budget. Reviewers praised most aspects of the production, with particular emphasis on Mendes, Spacey and Ball; criticism tended to focus on the familiarity of the characters and setting. DreamWorks launched a major campaign to increase American Beauty's chances of Oscar success following its controversial Best Picture snubs for Saving Private Ryan (1998) the previous year.

At the 72nd Academy Awards, the film won several Oscars, including Best Picture, along with Best Director for Mendes, Best Actor for Spacey, Best Original Screenplay for Ball, and Best Cinematography for Hall. The film was nominated for and won many other awards and honors, mainly for directing, writing, and acting. Retrospective reviews have been more mixed, with criticism towards the screenplay, social commentary, and parallels between the film's protagonist and allegations of sexual misconduct against Spacey.[3][4]

Plot

Middle-aged executive Lester Burnham hates his job and is unhappily married to neurotic and ambitious real estate broker Carolyn. Their 16-year-old daughter, Jane, abhors her parents and has low self esteem. Retired US Marine colonel Frank Fitts, his near-catatonic wife Barbara, and their teenage son Ricky move in next door. Ricky documents the world around him with a camcorder, collecting recordings on videotape in his bedroom, while using his part-time catering jobs as a front for dealing cannabis. Strict disciplinarian Frank has previously had Ricky committed to a psychiatric hospital and sent to military academy. Gay couple Jim Olmeyer and Jim Berkley, also neighbors to the Burnhams, welcome the Fitts family. Frank reveals his animus towards homosexuality later when angrily discussing the encounter with Ricky.

During a dance routine at a school basketball game, Lester becomes infatuated with Jane's cheerleader friend, Angela. He starts having sexual fantasies about her in which red rose petals are a recurring motif. Carolyn begins an affair with married business rival Buddy Kane. Lester is informed by his supervisor that he is to be laid off; Lester blackmails him into giving him an indulgent severance package and starts working at a drive-through restaurant. He buys his dream car, a 1970 Pontiac Firebird, and starts working out after overhearing Angela teasing Jane that she would have sex with him if he improved his physique. He begins smoking cannabis supplied by Ricky and flirts with Angela. The girls' friendship wanes when Jane starts a relationship with Ricky whom Angela scoffs at. Ricky and Jane bond over what Ricky considers the most beautiful image he has ever filmed: a plastic bag blowing in the wind.

Lester discovers Carolyn's infidelity when she and Kane unknowingly go to Lester's drive-through. He reacts with smug satisfaction. Buddy fears a costly divorce and ends the affair, while Carolyn is humiliated and simultaneously frustrated by her lack of professional success. Frank, suspicious of Lester and Ricky's friendship, finds footage Ricky captured by chance of Lester lifting weights naked and wrongly concludes they are sexually involved. He viciously accuses Ricky of prostitution which Ricky falsely admits, and goads his father into throwing him out. Carolyn, sitting distraught in her car, withdraws a handgun from the glove box. At home, Jane is arguing with Angela over her flirtation with Lester when Ricky interrupts to ask Jane to leave with him for New York City. He calls Angela ugly, boring, and ordinary.

Frank tentatively approaches Lester then breaks down and tearfully embraces him. Lester begins to comfort Frank until Frank attempts to kiss him. Lester gently rebuffs him, saying he had misunderstood, and Frank walks back out into the rain. Lester finds Angela sitting alone in the dark. He consoles her, saying she is beautiful and anything but ordinary. He asks what she wants and she says she does not know. She asks him what he wants and he says he has always wanted her. He takes her to the couch and as he begins to undress her, Angela admits her virginity. Lester is taken aback to realize her apparent experience was a veil for her innocence and he cannot continue.

Lester comforts her as they share their frustrations in life. Angela goes to the bathroom as Lester smiles at a family photograph, when an unseen figure shoots Lester in the back of the head at point-blank range. Ricky and Jane find Lester's body. Carolyn is in her closet discarding her gun, and crying hysterically as she hugs Lester’s clothing. A bloodied Frank, wearing surgical gloves, returns home: a gun is missing from his collection.

Lester's closing narration describes meaningful experiences during his life; he says that, despite his death, he is happy there is still so much beauty in the world.

Cast

- Kevin Spacey as Lester Burnham

- Annette Bening as Carolyn Burnham

- Thora Birch as Jane Burnham

- Wes Bentley as Ricky Fitts

- Mena Suvari as Angela Hayes

- Peter Gallagher as Buddy Kane

- Allison Janney as Barbara Fitts

- Chris Cooper as Col. Frank Fitts

- Scott Bakula as Jim Olmeyer

- Sam Robards as Jim Berkley

Themes and analysis

Multiple interpretations

Scholars and academics have offered many possible readings of American Beauty; film critics are similarly divided, not so much about the quality of the film, as their interpretations of it.[5] Described by many as about "the meaning of life" or "the hollow existence of the American suburbs",[6] the film has defied categorization by even the filmmakers. Mendes is indecisive, saying the script seemed to be about something different each time he read it: "a mystery story, a kaleidoscopic journey through American suburbia, a series of love stories; ... it was about imprisonment, ... loneliness, [and] beauty. It was funny; it was angry, sad."[7] The literary critic and author Wayne C. Booth concludes that the film resists any one interpretation: "[American Beauty] cannot be adequately summarized as 'here is a satire on what's wrong with American life'; that plays down the celebration of beauty. It is more tempting to summarize it as 'a portrait of the beauty underlying American miseries and misdeeds', but that plays down the scenes of cruelty and horror, and Ball's disgust with mores. It cannot be summarized with either Lester or Ricky's philosophical statements about what life is or how one should live."[5] He argues that the problem of interpreting the film is tied with that of finding its center—a controlling voice who "[unites] all of the choices".[nb 1][7] He contends that in American Beauty's case, it is neither Mendes nor Ball.[8] Mendes considers the voice to be Ball's, but even while the writer was "strongly influential" on set,[7] he often had to accept deviations from his vision,[8] particularly ones that transformed the cynical tone of his script into something more optimistic.[9] With "innumerable voices intruding on the original author's," Booth says, those who interpret American Beauty "have forgotten to probe for the elusive center". According to Booth, the film's true controller is the creative energy "that hundreds of people put into its production, agreeing and disagreeing, inserting and cutting".[5]

Imprisonment and redemption

Mendes called American Beauty a rite of passage film about imprisonment and escape from imprisonment. The monotony of Lester's existence is established through his gray, nondescript workplace and characterless clothing.[10] In these scenes, he is often framed as if trapped, "reiterating rituals that hardly please him". He masturbates in the confines of his shower;[12] the shower stall evokes a jail cell and the shot is the first of many where Lester is confined behind bars or within frames,[10][11] such as when he is reflected behind columns of numbers on a computer monitor, "confined [and] nearly crossed out".[12] The academic and author Jody W. Pennington argues that Lester's journey is the story's center.[13] His sexual reawakening through meeting Angela is the first of several turning points as he begins to "[throw] off the responsibilities of the comfortable life he has come to despise".[14] After Lester shares a joint with Ricky, his spirit is released and he begins to rebel against Carolyn.[15] Changed by Ricky's "attractive, profound confidence", he is convinced that Angela is attainable and sees that he must question his "banal, numbingly materialist suburban existence"; he takes a job at a fast-food outlet, which allows him to regress to a point when he could "see his whole life ahead of him".[16]

When Lester is caught masturbating by Carolyn, his angry retort about their lack of intimacy is the first time he says aloud what he thinks about her.[17] By confronting the issue and Carolyn's "superficial investments in others", he is trying to "regain a voice in a home that [only respects] the voices of mother and daughter".[16] His final turning point comes when he and Angela almost have sex;[18] after she confesses her virginity, he no longer thinks of her as a sex object, but as a daughter.[19] He holds her close and "wraps her up". Mendes called it "the most satisfying end to [Lester's] journey there could possibly have been". With these final scenes, Mendes intended to show him at the conclusion of a "mythical quest". After Lester gets a beer from the refrigerator, the camera pushes toward him, then stops facing a hallway down which he walks "to meet his fate".[18][20] Having begun to act his age again, Lester achieves closure.[19] As he smiles at a family photo, the camera pans slowly from Lester to the kitchen wall, onto which blood spatters as a gunshot rings out; the slow pan reflects the peace of his death.[21] His body is discovered by Jane and Ricky. Mendes said that Ricky's staring into Lester's dead eyes is "the culmination of the theme" of the film: that beauty is found where it is least expected.[22]

Conformity and beauty

Like other American films of 1999—such as Fight Club, Bringing Out the Dead and Magnolia, American Beauty instructs its audience to "[lead] more meaningful lives".[23] The film argues the case against conformity, but does not deny that people need and want it; even the gay characters just want to fit in.[24] Jim and Jim, the Burnhams' other neighbors, are a satire of "gay bourgeois coupledom",[25] who "[invest] in the numbing sameness" that the film criticizes in heterosexual couples.[nb 2][26] The feminist academic and author Sally R. Munt argues that American Beauty uses its "art house" trappings to direct its message of nonconformity primarily to the middle classes, and that this approach is a "cliché of bourgeois preoccupation; ... the underlying premise being that the luxury of finding an individual 'self' through denial and renunciation is always open to those wealthy enough to choose, and sly enough to present themselves sympathetically as a rebel."[14]

Professor Roy M. Anker argues that the film's thematic center is its direction to the audience to "look closer". The opening combines an unfamiliar viewpoint of the Burnhams' neighborhood with Lester's narrated admission that this is the last year of his life, forcing audiences to consider their own mortality and the beauty around them.[27] It also sets a series of mysteries; Anker asks, "from what place exactly, and from what state of being, is he telling this story? If he's already dead, why bother with whatever it is he wishes to tell about his last year of being alive? There is also the question of how Lester has died—or will die." Anker believes the preceding scene—Jane's discussion with Ricky about the possibility of his killing her father—adds further mystery.[28] Professor Ann C. Hall disagrees; she says by presenting an early resolution to the mystery, the film allows the audience to put it aside "to view the film and its philosophical issues".[29] Through this examination of Lester's life, rebirth and death, American Beauty satirizes American middle class notions of meaning, beauty and satisfaction.[30] Even Lester's transformation only comes about because of the possibility of sex with Angela; he therefore remains a "willing devotee of the popular media's exaltation of pubescent male sexuality as a sensible route to personal wholeness".[31] Carolyn is similarly driven by conventional views of happiness; from her belief in "house beautiful" domestic bliss to her car and gardening outfit, Carolyn's domain is a "fetching American millennial vision of Pleasantville, or Eden".[32] The Burnhams are unaware that they are "materialists philosophically, and devout consumers ethically" who expect the "rudiments of American beauty" to give them happiness. Anker argues that "they are helpless in the face of the prettified economic and sexual stereotypes ... that they and their culture have designated for their salvation."[33]

The film presents Ricky as its "visionary, ... spiritual and mystical center".[34] He sees beauty in the minutiae of everyday life, videoing as much as he can for fear of missing it. He shows Jane what he considers the most beautiful thing he has filmed: a plastic bag, tossing in the wind in front of a wall. He says capturing the moment was when he realized that there was "an entire life behind things"; he feels that "sometimes there's so much beauty in the world I feel like I can't take it... and my heart is going to cave in." Anker argues that Ricky, in looking past the "cultural dross", has "[grasped] the radiant splendor of the created world" to see God.[35] As the film progresses, the Burnhams move closer to Ricky's view of the world.[36] Lester only forswears personal satisfaction at the film's end. On the cusp of having sex with Angela, he returns to himself after she admits her virginity. Suddenly confronted with a child, he begins to treat her as a daughter; in doing so, Lester sees himself, Angela, and his family "for the poor and fragile but wondrous creatures they are". He looks at a picture of his family in happier times,[37] and dies having had an epiphany that infuses him with "wonder, joy, and soul-shaking gratitude"—he has finally seen the world as it is.[30]

According to Patti Bellantoni, colors are used symbolically throughout the film,[38] none more so than red, which is an important thematic signature that drives the story and "[defines] Lester's arc". First seen in drab colors that reflect his passivity, Lester surrounds himself with red as he regains his individuality.[39] The American Beauty rose is repeatedly used as symbol; when Lester fantasizes about Angela, she is usually naked and surrounded by rose petals. In these scenes, the rose symbolizes Lester's desire for her. When associated with Carolyn, the rose represents a "façade for suburban success".[13] Roses are included in almost every shot inside the Burnhams' home, where they signify "a mask covering a bleak, unbeautiful reality".[33] Carolyn feels that "as long as there can be roses, all is well".[33] She cuts the roses and puts them in vases,[13] where they adorn her "meretricious vision of what makes for beauty"[33] and begin to die.[13] The roses in the vase in the Angela–Lester seduction scene symbolize Lester's previous life and Carolyn; the camera pushes in as Lester and Angela get closer, finally taking the roses—and thus Carolyn—out of the shot.[18] Lester's epiphany at the end of the film is expressed by rain and the use of red, building to a crescendo that is a deliberate contrast to the release Lester feels.[40] The constant use of red "lulls [the audience] subliminally" into becoming used to it; consequently, it leaves the audience unprepared when Lester is shot and his blood spatters on the wall.[39]

Sexuality and repression

Pennington argues that American Beauty defines its characters through their sexuality. Lester's attempts to relive his youth are a direct result of his lust for Angela,[13] and the state of his relationship with Carolyn is in part shown through their lack of sexual contact. Also sexually frustrated, Carolyn has an affair that takes her from "cold perfectionist" to more of a carefree soul who "[sings] happily along with" the music in her car.[41] Jane and Angela constantly reference sex, through Angela's descriptions of her supposed sexual encounters and the way the girls address each other.[41] Their nude scenes are used to communicate their vulnerability.[18][42] By the end of the film, Angela's hold on Jane has weakened until the only power she has over her friend is Lester's attraction to her.[43] Col. Fitts reacts with disgust to meeting Jim and Jim; he asks, "How come these faggots always have to rub it in your face? How can they be so shameless?" To which Ricky replies, "That's the thing, Dad—they don't feel like it's anything to be ashamed of." Pennington argues that Col. Fitts' reaction is not homophobic, but an "anguished self-interrogation".[44]

With other turn-of-the-millennium films such as Fight Club (1999), In the Company of Men (1997), American Psycho (2000), and Boys Don't Cry (1999), American Beauty "raises the broader, widely explored issue of masculinity in crisis".[45] Professor Vincent Hausmann charges that in their reinforcement of masculinity "against threats posed by war, by consumerism, and by feminist and queer challenges", these films present a need to "focus on, and even to privilege" aspects of maleness "deemed 'deviant'". Lester's transformation conveys "that he, and not the woman, has borne the brunt of [lack of being]"[nb 3] and he will not stand for being emasculated.[45] Lester's attempts to "strengthen traditional masculinity" conflict with his responsibilities as a father. Although the film portrays the way Lester returns to that role positively, he does not become "the hypermasculine figure implicitly celebrated in films like Fight Club". Hausmann concludes that Lester's behavior toward Angela is "a misguided but nearly necessary step toward his becoming a father again".[12]

Hausmann says the film "explicitly affirms the importance of upholding the prohibition against incest";[46] a recurring theme of Ball's work is his comparison of the taboos against incest and homosexuality.[47] Instead of making an overt distinction, American Beauty looks at how their repression can lead to violence.[48] Col. Fitts is so ashamed of his homosexuality that it drives him to murder Lester.[44] Ball said, "The movie is in part about how homophobia is based in fear and repression and about what [they] can do."[49] The film implies two unfulfilled incestuous desires:[24] Lester's pursuit of Angela is a manifestation of his lust for his own daughter,[50] while Col. Fitts' repression is exhibited through the almost sexualized discipline with which he controls Ricky.[24] Consequently, Ricky realizes that he can only hurt his father by falsely telling him he is homosexual, while Angela's vulnerability and submission to Lester reminds him of his responsibilities and the limits of his fantasy.[43] Col. Fitts represents Ball's father,[51] whose repressed homosexual desires led to his own unhappiness.[52] Ball rewrote Col. Fitts to delay revealing him as homosexual.[48]

Temporality and music

American Beauty follows a traditional narrative structure, only deviating with the displaced opening scene of Jane and Ricky from the middle of the story. Although the plot spans one year, the film is narrated by Lester at the moment of his death. Jacqueline Furby says that the plot "occupies ... no time [or] all time", citing Lester's claim that life did not flash before his eyes, but that it "stretches on forever like an ocean of time".[53] Furby argues that a "rhythm of repetition" forms the core of the film's structure.[54] For example, two scenes have the Burnhams sitting down to an evening meal, shot from the same angle. Each image is broadly similar, with minor differences in object placement and body language that reflect the changed dynamic brought on by Lester's new-found assertiveness.[55][56] Another example is the pair of scenes in which Jane and Ricky film each other. Ricky films Jane from his bedroom window as she removes her bra, and the image is reversed later for a similarly "voyeuristic and exhibitionist" scene in which Jane films Ricky at a vulnerable moment.[53]

Lester's fantasies are emphasized by slow- and repetitive-motion shots;[58] Mendes uses double-and-triple cutbacks in several sequences,[17][59] and the score alters to make the audience aware that it is entering a fantasy.[60] One example is the gymnasium scene—Lester's first encounter with Angela. While the cheerleaders perform their half-time routine to "On Broadway", Lester becomes increasingly fixated on Angela. Time slows to represent his "voyeuristic hypnosis" and Lester begins to fantasize that Angela's performance is for him alone.[61] "On Broadway"—which provides a conventional underscore to the onscreen action—is replaced by discordant, percussive music that lacks melody or progression. This nondiegetic score is important to creating the narrative stasis in the sequence;[62] it conveys a moment for Lester that is stretched to an indeterminate length. The effect is one that Stan Link likens to "vertical time", described by the composer and music theorist Jonathan Kramer as music that imparts "a single present stretched out into an enormous duration, a potentially infinite 'now' that nonetheless feels like an instant".[nb 4] The music is used like a visual cue, so that Lester and the score are staring at Angela. The sequence ends with the sudden reintroduction of "On Broadway" and teleological time.[57]

According to Drew Miller of Stylus, the soundtrack "[gives] unconscious voice" to the characters' psyches and complements the subtext. The most obvious use of pop music "accompanies and gives context to" Lester's attempts to recapture his youth; reminiscent of how the counterculture of the 1960s combated American repression through music and drugs, Lester begins to smoke cannabis and listen to rock music.[nb 5] Mendes' song choices "progress through the history of American popular music". Miller argues that although some may be over familiar, there is a parodic element at work, "making good on [the film's] encouragement that viewers look closer". Toward the end of the film, Thomas Newman's score features more prominently, creating "a disturbing tempo" that matches the tension of the visuals. The exception is "Don't Let It Bring You Down", which plays during Angela's seduction of Lester. At first appropriate, its tone clashes as the seduction stops. The lyrics, which speak of "castles burning", can be seen as a metaphor for Lester's view of Angela—"the rosy, fantasy-driven exterior of the 'American Beauty'"—as it burns away to reveal "the timid, small-breasted girl who, like his wife, has willfully developed a false public self".[63]

Production

Development

Ball began writing American Beauty as a play in the early 1990s, partly inspired by the media circus that accompanied the Amy Fisher trial in 1992.[64] He shelved the play after deciding that the story would not work on stage. After spending the next few years writing for television, Ball revived the idea in 1997 when attempting to break into the film industry after several frustrating years writing for the television sitcoms Grace Under Fire and Cybill. He joined the United Talent Agency, where his representative, Andrew Cannava, suggested he write a spec script to "reintroduce [himself] to the town as a screenwriter". Ball pitched three ideas to Cannava: two conventional romantic comedies and American Beauty.[nb 6][66] Despite the story's lack of an easily marketable concept, Cannava selected American Beauty because he felt it was the one for which Ball had the most passion.[67] While developing the script, Ball created another television sitcom, Oh, Grow Up. He channeled his anger and frustration at having to accede to network demands on that show—and during his tenures on Grace Under Fire and Cybill—into writing American Beauty.[66]

Ball did not expect to sell the script, believing it would act as more of a calling card, but American Beauty drew interest from several production bodies.[68] Cannava passed the script to several producers, including Dan Jinks and Bruce Cohen, who took it to DreamWorks.[69] With the help of executives Glenn Williamson and Bob Cooper, and Steven Spielberg in his capacity as studio partner, Ball was convinced to develop the project at DreamWorks;[70] he received assurances from the studio—known at the time for its more conventional fare—that it would not "iron the [edges] out".[nb 7][68] In an unusual move, DreamWorks decided not to option the script;[71] instead, in April 1998, the studio bought it outright[72] for $250,000,[73] outbidding Fox Searchlight Pictures, October Films, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and Lakeshore Entertainment.[74] DreamWorks planned to make the film for $6–8 million.[75]

Jinks and Cohen involved Ball throughout the film's development, including casting and director selection. The producers met with about twenty interested directors,[76] several of whom were considered A-list at the time. Ball was not keen on the more well-known directors because he believed their involvement would increase the budget and lead DreamWorks to become "nervous about the content".[77] Nevertheless, the studio offered the film to Mike Nichols and Robert Zemeckis; neither accepted.[75] In the same year, Mendes (then a theater director) revived the musical Cabaret in New York with fellow director Rob Marshall. Beth Swofford of the Creative Artists Agency arranged meetings for Mendes with studio figures in Los Angeles to see if film direction was a possibility.[nb 8] Mendes came across American Beauty in a pile of eight scripts at Swofford's house,[79] and knew immediately that it was the one he wanted to make; early in his career, he had been inspired by how the film Paris, Texas (1984) presented contemporary America as a mythic landscape and he saw the same theme in American Beauty, as well as parallels with his own childhood.[80] Mendes later met with Spielberg; impressed by Mendes' productions of Oliver! and Cabaret,[65] Spielberg encouraged him to consider American Beauty.[75]

Mendes found that he still had to convince DreamWorks' production executives to let him direct.[75] He had already discussed the film with Jinks and Cohen, and felt they supported him.[81] Ball was also keen; having seen Cabaret, he was impressed with Mendes' "keen visual sense" and thought he did not make obvious choices. Ball felt that Mendes liked to look under the story's surface, a talent he felt would be a good fit with the themes of American Beauty.[77] Mendes' background also reassured him, because of the prominent role the playwright usually has in a theater production.[76] Over two meetings—the first with Cooper, Walter Parkes, and Laurie MacDonald,[81] the second with Cooper alone[82]—Mendes pitched himself to the studio.[81] The studio soon approached Mendes with a deal to direct for the minimum salary allowed under Directors Guild of America rules—$150,000. Mendes accepted, and later recalled that after taxes and his agent's commission, he only earned $38,000.[82] In June 1998, DreamWorks confirmed that it had contracted Mendes to direct the film.[83]

Writing

"I think I was writing about ... how it's becoming harder and harder to live an authentic life when we live in a world that seems to focus on appearance. ... For all the differences between now and the [1950s], in a lot of ways this is just as oppressively conformist a time. ... You see so many people who strive to live the unauthentic life and then they get there and they wonder why they're not happy. ... I didn't realize it when I sat down to write [American Beauty], but these ideas are important to me."

—Alan Ball, 2000[84]

Ball was partly inspired by two encounters he had in the early 1990s. In about 1991–92, Ball saw a plastic bag blowing in the wind outside the World Trade Center. He watched the bag for ten minutes, saying later that it provoked an "unexpected emotional response".[85] In 1992, Ball became preoccupied with the media circus that accompanied the Amy Fisher trial.[67] Discovering a comic book telling of the scandal, he was struck by how quickly it had become commercialized.[64] He said he "felt like there was a real story underneath [that was] more fascinating and way more tragic" than the story presented to the public,[67] and attempted to turn the idea into a play. Ball produced around 40 pages,[64] but stopped when he realized it would work better as a film.[67] He felt that because of the visual themes, and because each character's story was "intensely personal", it could not be done on a stage. All the main characters appeared in this version, but Carolyn did not feature strongly; Jim and Jim instead had much larger roles.[86]

Ball based Lester's story on aspects of his own life.[87] Lester's re-examination of his life parallels feelings Ball had in his mid-30s;[88] like Lester, Ball put aside his passions to work in jobs he hated for people he did not respect.[87] Scenes in Ricky's household reflect Ball's own childhood experiences.[68] Ball suspected his father was homosexual and used the idea to create Col. Fitts, a man who "gave up his chance to be himself".[89] Ball said the script's mix of comedy and drama was not intentional, but that it came unconsciously from his own outlook on life. He said the juxtaposition produced a starker contrast, giving each trait more impact than if they appeared alone.[90]

In the script that was sent to prospective actors and directors, Lester and Angela had sex;[91] by the time of shooting, Ball had rewritten the scene to the final version.[92] Ball initially rebuffed counsel from others that he change the script, feeling they were being puritanical; the final impetus to alter the scene came from DreamWorks' then-president Walter Parkes. He convinced Ball by indicating that in Greek mythology, the hero "has a moment of epiphany before ... tragedy occurs".[93] Ball later said his anger when writing the first draft had blinded him to the idea that Lester needed to refuse sex with Angela to complete his emotional journey—to achieve redemption.[92] Jinks and Cohen asked Ball not to alter the scene right away, as they felt it would be inappropriate to make changes to the script before a director had been hired.[94] Early drafts also included a flashback to Col. Fitts' service in the Marines, a sequence that unequivocally established his homosexual leanings. In love with another Marine, Col. Fitts sees the man die and comes to believe that he is being punished for the "sin" of being gay. Ball removed the sequence because it did not fit the structure of the rest of the film—Col. Fitts was the only character to have a flashback[95]—and because it removed the element of surprise from Col. Fitts' later pass at Lester.[94] Ball said he had to write it for his own benefit to know what happened to Col. Fitts, though all that remained in later drafts was subtext.[95]

Ball remained involved throughout production;[76] he had signed a television show development deal, so had to get permission from his producers to take a year off to be close to American Beauty.[91] Ball was on-set for rewrites and to help interpret his script for all but two days of filming.[96] His original bookend scenes—in which Ricky and Jane are prosecuted for Lester's murder after being framed by Col. Fitts[97]—were excised in post-production;[67] the writer later felt the scenes were unnecessary, saying they were a reflection of his "anger and cynicism" at the time of writing (see "Editing").[90] Ball and Mendes revised the script twice before it was sent to the actors, and twice more before the first read-through.[77] The script was written between June 1997 and February 1998.[98]

The shooting script features a scene in Angela's car in which Ricky and Jane talk about death and beauty; the scene differed from earlier versions, which set it as a "big scene on a freeway"[99] in which the three witness a car crash and see a dead body.[100] The change was a practical decision, as the production was behind schedule and they needed to cut costs.[99] The schedule called for two days to be spent filming the crash, but only half a day was available.[100] Ball agreed, but only if the scene could retain a line of Ricky's where he reflects on having once seen a dead homeless woman: "When you see something like that, it's like God is looking right at you, just for a second. And if you're careful, you can look right back." Jane asks: "And what do you see?" Ricky: "Beauty." Ball said, "They wanted to cut that scene. They said it's not important. I said, 'You're out of your fucking mind. It's one of the most important scenes in the movie!' ... If any one line is the heart and soul of this movie, that is the line."[99] Another scene was rewritten to accommodate the loss of the freeway sequence; set in a schoolyard, it presents a "turning point" for Jane in that she chooses to walk home with Ricky instead of going with Angela.[100] By the end of filming, the script had been through ten drafts.[77]

Casting

First row: Wes Bentley, Chris Cooper, Mena Suvari, Kevin Spacey

Second row: Annette Bening, Thora Birch, Allison Janney

Mendes had Spacey and Bening in mind for the leads from the beginning, but DreamWorks executives were unenthusiastic. The studio suggested several alternatives, including Bruce Willis, Kevin Costner, and John Travolta to play Lester (the role was also offered to Chevy Chase, but he turned it down),[101] while Helen Hunt or Holly Hunter were proposed to play Carolyn. Mendes did not want a big star "weighing the film down"; he felt Spacey was the right choice based on his performances in the 1995 films The Usual Suspects and Seven, and 1992's Glengarry Glen Ross.[102] Spacey was surprised; he said, "I usually play characters who are very quick, very manipulative and smart. ... I usually wade in dark, sort of treacherous waters. This is a man living one step at a time, playing by his instincts. This is actually much closer to me, to what I am, than those other parts."[73] Mendes offered Bening the role of Carolyn without the studio's consent; although executives were upset at Mendes,[102] by September 1998, DreamWorks had entered negotiations with Spacey and Bening.[103][104]

Spacey loosely based Lester's early "schlubby" deportment on Walter Matthau.[105] During the film, Lester's physique improves from flabby to toned;[106] Spacey worked out during filming to improve his body,[107] but because Mendes shot the scenes out of chronological order, Spacey varied postures to portray the stages.[106] Before filming, Mendes and Spacey analyzed Jack Lemmon's performance in The Apartment (1960), because Mendes wanted Spacey to emulate "the way [Lemmon] moved, the way he looked, the way he was in that office and the way he was an ordinary man and yet a special man".[73] Spacey's voiceover is a throwback to Sunset Boulevard (1950), which is also narrated in retrospect by a dead character. Mendes felt it evoked Lester's—and the film's—loneliness.[10] Bening recalled women from her youth to inform her performance: "I used to babysit constantly. You'd go to church and see how people present themselves on the outside, and then be inside their house and see the difference." Bening and a hair stylist collaborated to create a "PTA president coif" hairstyle, and Mendes and production designer Naomi Shohan researched mail-order catalogs to better establish Carolyn's environment of a "spotless suburban manor".[108] To help Bening get into Carolyn's mindset, Mendes gave her music that he believed Carolyn would like.[109] He lent Bening the Bobby Darin version of the song "Don't Rain on My Parade", which she enjoyed and persuaded the director to include it for a scene in which Carolyn sings in her car.[108]

Kirsten Dunst was offered the role of Angela Hayes but she turned it down.[110]

For the roles of Jane, Ricky, and Angela, DreamWorks gave Mendes carte blanche.[111] By November 1998, Thora Birch, Wes Bentley, and Mena Suvari had been cast in the parts[112]—in Birch's case, despite the fact she was 16 years old and was deemed underage for a brief nude scene, which her parents had to approve. Child labor representatives accompanied Birch's parents on set during the filming of the nude scene.[113][114] Bentley overcame competition from top actors under the age of 25 to be cast.[112] The 2009 documentary My Big Break followed Bentley, and several other young actors, before and after he landed the part.[115] To prepare, Mendes provided Bentley with a video camera, telling the actor to film what Ricky would.[109] Peter Gallagher and Allison Janney were cast (as Buddy Kane and Barbara Fitts) after filming began in December 1998.[116][117] Mendes gave Janney a book of paintings by Edvard Munch. He told her, "Your character is in there somewhere."[109] Mendes cut much of Barbara's dialogue,[118] including conversations between Colonel Frank Fitts and her, as he felt that what needed to be said about the pair—their humanity and vulnerability—was conveyed successfully through their shared moments of silence.[119] Chris Cooper plays Colonel Frank Fitts, Scott Bakula plays Jim Olmeyer, and Sam Robards plays Jim Berkley.[120] Jim and Jim were deliberately depicted as the most normal, happy—and boring—couple in the film.[49] Ball's inspiration for the characters came from a thought he had after seeing a "bland, boring, heterosexual couple" who wore matching clothes: "I can't wait for the time when a gay couple can be just as boring." Ball also included aspects of a gay couple he knew who had the same forename.[89]

Mendes insisted on two weeks of cast rehearsals, although the sessions were not as formal as he was used to in the theater, and the actors could not be present at every one.[109] Several improvisations and suggestions by the actors were incorporated into the script.[77] An early scene showing the Burnhams leaving home for work was inserted later on to show the low point that Carolyn and Lester's relationship had reached.[10] Spacey and Bening worked to create a sense of the love that Lester and Carolyn once had for one another; for example, the scene in which Lester almost seduces Carolyn after the pair argues over Lester's buying a car was originally "strictly contentious".[121]

Filming

Principal photography lasted about 50 days,[122] from December 14, 1998[123] to February 1999.[124] American Beauty was filmed on soundstages at the Warner Bros. backlot in Burbank, California, and at Hancock Park and Brentwood in Los Angeles.[40] The aerial shots at the beginning and end of the film were captured in Sacramento, California,[125] and many of the school scenes were shot at South High School in Torrance, California; several extras in the gym crowd were South High students.[126] The film is set in an upper middle-class neighborhood in an unidentified American town. Production designer Naomi Shohan likened the locale to Evanston, Illinois, but said, "it's not about a place, it's about an archetype... The milieu was pretty much Anywhere, USA—upwardly mobile suburbia." The intent was for the setting to reflect the characters, who are also archetypes. Shohan said, "All of them are very strained, and their lives are constructs." The Burnhams' household was designed as the reverse of the Fitts'—the former a pristine ideal, but graceless and lacking in "inner balance", leading to Carolyn's desire to at least give it the appearance of a "perfect all-American household"; the Fitts' home is depicted in "exaggerated darkness [and] symmetry".[40]

The production selected two adjacent properties on the Warner backlot's "Blondie Street" for the Burnham and Fitts' homes.[nb 9][40] The crew rebuilt the houses to incorporate false rooms that established lines of sight—between Ricky and Jane's bedroom windows, and between Ricky's bedroom and Lester's garage.[127] The garage windows were designed specifically to obtain the crucial shot toward the end of the film in which Col. Fitts—watching from Ricky's bedroom—mistakenly assumes that Lester is paying Ricky for sex.[107] Mendes made sure to establish the line of sight early on in the film to make the audience feel a sense of familiarity with the shot.[128] The house interiors were filmed on the backlot, on location, and on soundstages when overhead shots were needed.[40] The inside of the Burnhams' home was shot at a house close to Interstate 405 and Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles; the inside of the Fitts' home was shot in the city's Hancock Park neighborhood.[127] Ricky's bedroom was designed to be cell-like to suggest his "monkish" personality, while at the same time blending with the high-tech equipment to reflect his voyeuristic side. The production deliberately minimized the use of red, as it was an important thematic signature elsewhere. The Burnhams' home uses cool blues, while the Fitts' is kept in a "depressed military palette".[40]

Mendes' dominating visual style was deliberate and composed, with a minimalist design that provided "a sparse, almost surreal feeling—a bright, crisp, hard edged, near Magritte-like take on American suburbia"; Mendes constantly directed his set dressers to empty the frame. He made Lester's fantasy scenes "more fluid and graceful",[20] and Mendes made minimal use of steadicams, feeling that stable shots generated more tension. For example, when Mendes used a slow push in to the Burnhams' dinner table, he held the shot because his training as a theater director taught him the importance of putting distance between the characters. He wanted to keep the tension in the scene, so he only cut away when Jane left the table.[nb 10][105] Mendes used a hand-held camera for the scene in which Col. Fitts beats Ricky. Mendes said the camera provided the scene with a "kinetic ... off-balance energy". He also went hand-held for the excerpts of Ricky's camcorder footage.[42] Mendes took a long time to get the quality of Ricky's footage to the level he wanted.[105] For the plastic-bag footage, Mendes used wind machines to move the bag in the air. The scene took four takes; two by the second unit did not satisfy Mendes, so he shot the scene himself. He felt his first take lacked grace, but for the last attempt, he changed the location to the front of a brick wall and added leaves on the ground. Mendes was satisfied by the way the wall gave definition to the outline of the bag.[130]

Mendes avoided using close-ups, as he believed the technique was overused; he also cited Spielberg's advice that he should imagine an audience silhouetted at the bottom of the camera monitor, to keep in mind that he was shooting for display on a 40-foot (10 m) screen.[18] Spielberg—who visited the set a few times—also advised Mendes not to worry about costs if he had a "great idea" toward the end of a long working day. Mendes said, "That happened three or four times, and they are all in the movie."[131] Despite Spielberg's support, DreamWorks and Mendes fought constantly over the schedule and budget, although the studio interfered little with the film's content.[20] Spacey, Bening and Hall worked for significantly less than their usual rates. American Beauty cost DreamWorks $15 million to produce, slightly above their projected sum.[132] Mendes was so dissatisfied with his first three days' filming that he obtained permission from DreamWorks to reshoot the scenes. He said, "I started with a wrong scene, actually, a comedy scene.[nb 11] And the actors played it way too big: ... it was badly shot, my fault, badly composed, my fault, bad costumes, my fault ...; and everybody was doing what I was asking. It was all my fault." Aware that he was a novice, Mendes drew on the experience of Hall: "I made a very conscious decision early on, if I didn't understand something technically, to say, without embarrassment, 'I don't understand what you're talking about, please explain it.'"[73]

Mendes encouraged some improvisation; for example, when Lester masturbates in bed beside Carolyn, the director asked Spacey to improvise several euphemisms for the act in each take. Mendes said, "I wanted that not just because it was funny ... but because I didn't want it to seem rehearsed. I wanted it to seem like he was blurting it out of his mouth without thinking. [Spacey] is so in control—I wanted him to break through." Spacey obliged, eventually coming up with 35 phrases, but Bening could not always keep a straight face, which meant the scene had to be shot ten times.[131] The production used small amounts of computer-generated imagery. Most of the rose petals in Lester's fantasies were added in post-production,[59] although some were real and had the wires holding them digitally removed.[133] When Lester fantasizes about Angela in a rose-petal bath, the steam was real, save for in the overhead shot. To position the camera, a hole had to be cut in the ceiling, through which the steam escaped; it was instead added digitally.[17]

Editing

American Beauty was edited by Christopher Greenbury and Tariq Anwar; Greenbury began in the position, but had to leave halfway through post-production because of a scheduling conflict with Me, Myself and Irene (2000). Mendes and an assistant edited the film for ten days between the appointments.[134] Mendes realized during editing that the film was different from the one he had envisioned. He believed he had been making a "much more whimsical, ... kaleidoscopic" film than what came together in the edit suite. Instead, Mendes was drawn to the emotion and darkness; he began to use the score and shots he had intended to discard to craft the film along these lines.[135] In total, he cut about 30 minutes from his original edit.[122] The opening included a dream in which Lester imagines himself flying above the town. Mendes spent two days filming Spacey against bluescreen, but removed the sequence as he believed it to be too whimsical—"like a Coen brothers movie"—and therefore inappropriate for the tone he was trying to set.[105] The opening in the final cut reused a scene from the middle of the film where Jane tells Ricky to kill her father.[10] This scene was to be the revelation to the audience that the pair was not responsible for Lester's death, as the way it was scored and acted made it clear that Jane's request was not serious. However, in the portion he used in the opening—and when the full scene plays out later—Mendes used the score and a reaction shot of Ricky to leave a lingering ambiguity as to his guilt.[136] The subsequent shot—an aerial view of the neighborhood—was originally intended as the plate shot for the bluescreen effects in the dream sequence.[105]

Mendes spent more time recutting the first ten minutes than the rest of the film taken together. He trialed several versions of the opening;[10] the first edit included bookend scenes in which Jane and Ricky are convicted of Lester's murder,[137] but Mendes excised these in the last week of editing[10] because he felt they made the film lose its mystery,[138] and because they did not fit with the theme of redemption that had emerged during production. Mendes believed the trial drew focus away from the characters and turned the film "into an episode of NYPD Blue". Instead, he wanted the ending to be "a poetic mixture of dream and memory and narrative resolution".[20] When Ball first saw a completed edit, it was a version with truncated versions of these scenes. He felt that they were so short that they "didn't really register". Mendes and he argued,[96] but Ball was more accepting after Mendes cut the sequences completely; Ball felt that without the scenes, the film was more optimistic and had evolved into something that "for all its darkness had a really romantic heart".[97]

Cinematography

Conrad Hall was not the first choice for director of photography; Mendes believed he was "too old and too experienced" to want the job, and he had been told that Hall was difficult to work with. Instead, Mendes asked Frederick Elmes, who turned the job down because he did not like the script.[139] Hall was recommended to Mendes by Tom Cruise, because of Hall's work on Without Limits (1998), which Cruise had executive produced. Mendes was directing Cruise's then-wife Nicole Kidman in the play The Blue Room during preproduction on American Beauty,[127] and had already storyboarded the whole film.[65] Hall was involved for one month during preproduction;[127] his ideas for lighting the film began with his first reading of the script, and further passes allowed him to refine his approach before meeting Mendes.[140] Hall was initially concerned that audiences would not like the characters; he only felt able to identify with them during cast rehearsals, which gave him fresh ideas on his approach to the visuals.[127]

Hall's approach was to create peaceful compositions that evoked classicism, to contrast with the turbulent on-screen events and allow audiences to take in the action. Hall and Mendes first discussed the intended mood of a scene, but he was allowed to light the shot in any way he felt necessary.[140] In most cases, Hall first lit the scene's subject by "painting in" the blacks and whites, before adding fill light, which he reflected from beadboard or white card on the ceiling. This approach gave Hall more control over the shadows while keeping the fill light unobtrusive and the dark areas free of spill.[141] Hall shot American Beauty in a 2.39:1 aspect ratio in the Super 35 format, primarily using Kodak Vision 500T 5279 35 mm film stock.[142] He used Super 35 partly because its larger scope allowed him to capture elements such as the corners of the petal-filled pool in its overhead shot, creating a frame around Angela within.[133] He shot the whole film at the same T-stop (T1.9);[142] given his preference for shooting that wide, Hall favored high-speed stocks to allow for more subtle lighting effects.[141] He used Panavision Platinum cameras with the company's Primo series of prime and zoom lenses. Hall employed Kodak Vision 200T 5274 and EXR 100T 5248 stock for scenes with daylight effects. He had difficulty adjusting to Kodak's newly introduced Vision release print stock, which, combined with his contrast-heavy lighting style, created a look with too much contrast. Hall contacted Kodak, who sent him a batch of 5279 that was five percent lower in contrast. Hall used a 1/8th strength Tiffen Black ProMist filter for almost every scene, which he said in retrospect may not have been the best choice, as the optical steps required to blow Super 35 up for its anamorphic release print led to a slight amount of degradation; therefore, the diffusion from the filter was not required. When he saw the film in a theater, Hall felt that the image was slightly unclear and that had he not used the filter, the diffusion from the Super 35–anamorphic conversion would have generated an image closer to what he originally intended.[142]

A shot where Lester and Ricky share a cannabis joint behind a building came from a misunderstanding between Hall and Mendes. Mendes asked Hall to prepare the shot in his absence; Hall assumed the characters would look for privacy, so he placed them in a narrow passage between a truck and the building, intending to light from the top of the truck. When Mendes returned, he explained that the characters did not care if they were seen. He removed the truck and Hall had to rethink the lighting; he lit it from the left, with a large light crossing the actors, and with a soft light behind the camera. Hall felt the consequent wide shot "worked perfectly for the tone of the scene".[142] Hall made sure to keep rain, or the suggestion of it, in every shot near the end of the film. In one shot during Lester's encounter with Angela at the Burnhams' home, Hall created rain effects on the foreground cross lights; in another, he partly lit the pair through French windows to which he had added material to make the rain run slower, intensifying the light (although the strength of the outside light was unrealistic for a night scene, Hall felt it justified because of the strong contrasts it produced). For the close-ups when Lester and Angela move to the couch, Hall tried to keep rain in the frame, lighting through the window onto the ceiling behind Lester.[141] He also used rain boxes to produce rain patterns where he wanted without lighting the entire room.[143]

Music

Thomas Newman's score was recorded in Santa Monica, California.[73] He used mainly percussion instruments to create the mood and rhythm, the inspiration for which was provided by Mendes.[144] Newman "favored pulse, rhythm, and color over melody", making for a more minimalist score than he had previously created. He built each cue around "small, endlessly repeating phrases"—often, the only variety through a "thinning of the texture for eight bars".[145] The percussion instruments included tablas, bongos, cymbals, piano, xylophones, and marimbas; also featured were guitars, flute, and world music instruments.[144] Newman also used electronic music and on "quirkier" tracks employed more unorthodox methods, such as tapping metal mixing bowls with a finger and using a detuned mandolin.[145] Newman believed the score helped move the film along without disturbing the "moral ambiguity" of the script: "It was a real delicate balancing act in terms of what music worked to preserve [that]."[144]

The soundtrack features songs by Newman, Bobby Darin, The Who, Free, Eels, The Guess Who, Bill Withers, Betty Carter, Peggy Lee, The Folk Implosion, Gomez, and Bob Dylan, as well as two cover versions—The Beatles' "Because", performed by Elliott Smith, and Neil Young's "Don't Let It Bring You Down", performed by Annie Lennox.[120] Produced by the film's music supervisor Chris Douridas,[146] an abridged soundtrack album was released on October 5, 1999, and went on to be nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Soundtrack Album. An album featuring 19 tracks from Newman's score was released on January 11, 2000, and won the Grammy Award for Best Score Soundtrack Album.[147] Filmmaker considered the score to be one of Newman's best, saying it "[enabled] the film's transcendentalist aspirations". In 2006, the magazine chose the score as one of twenty essential soundtracks it believed spoke to the "complex and innovative relationships between music and screen storytelling".[148]

Release

Publicity

DreamWorks contracted Amazon.com to create the official website, marking the first time that Amazon had created a special section devoted to a feature film. The website included an overview, a photo gallery, cast and crew filmographies, and exclusive interviews with Spacey and Bening.[149] The film's tagline—"look closer"—originally came from a cutting pasted on Lester's workplace cubicle by the set dresser.[105] DreamWorks ran parallel marketing campaigns and trailers—one aimed at adults, the other at teenagers. Both trailers ended with the poster image of a girl holding a rose.[nb 12][nb 13][152] Reviewing the posters of several films of the year, David Hochman of Entertainment Weekly rated American Beauty's highly, saying it evoked the tagline; he said, "You return to the poster again and again, thinking, this time you're gonna find something."[150] DreamWorks did not want to test screen the film; according to Mendes, the studio was pleased with it, but he insisted on one where he could question the audience afterward. The studio reluctantly agreed and showed the film to a young audience in San Jose, California. Mendes claimed the screening went very well.[nb 14][132]

Theatrical run

The film had its world premiere on September 8, 1999, at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre in Los Angeles.[153] Three days later, the film appeared at the Toronto International Film Festival.[154] With the filmmakers and cast in attendance, it screened at several American universities, including the University of California at Berkeley, New York University, the University of California at Los Angeles, the University of Texas at Austin, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Northwestern University.[155]

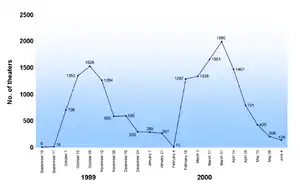

On September 15, 1999, American Beauty opened to the public in limited release at three theaters in Los Angeles and three in New York.[nb 15][158] More theaters were added during the limited run,[157] and on October 1, the film officially entered wide release[nb 16] by screening in 706 theaters across North America.[159] The film grossed $8,188,587 over the weekend, ranking third at the box office.[160] Audiences polled by the market research firm CinemaScore gave American Beauty a "B+" grade on average.[nb 17][162] The theater count hit a high of 1,528 at the end of the month, before a gradual decline.[157] Following American Beauty's wins at the 57th Golden Globe Awards, DreamWorks re-expanded the theater presence from a low of 7 in mid-February,[156] to a high of 1,990 in March.[157] The film ended its North American theatrical run on June 4, 2000, having grossed $130.1 million.[160]

American Beauty had its European premiere at the London Film Festival on November 18, 1999;[163] in January 2000, it began to screen in various territories outside North America.[164] It debuted in Israel to "potent" returns,[165] and limited releases in Germany, Italy, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Finland followed on January 21.[166] After January 28 opening weekends in Australia, the United Kingdom, Spain and Norway, American Beauty had earned $7 million in 12 countries for a total of $12.1 million outside North America.[167] On February 4, American Beauty debuted in France and Belgium. Expanding to 303 theaters in the United Kingdom, the film ranked first at the box office with $1.7 million.[168] On the weekend of February 18—following American Beauty's eight nominations for the 72nd Academy Awards—the film grossed $11.7 million from 21 territories, for a total of $65.4 million outside North America. The film had "dazzling" debuts in Hungary, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and New Zealand.[169]

As of February 18, the most successful territories were the United Kingdom ($15.2 million), Italy ($10.8 million), Germany ($10.5 million), Australia ($6 million), and France ($5.3 million).[169] The Academy Award nominations meant strong performances continued across the board;[170] the following weekend, American Beauty grossed $10.9 million in 27 countries, with strong debuts in Brazil, Mexico, and South Korea.[171] Other high spots included robust returns in Argentina, Greece, and Turkey.[170] On the weekend of March 3, 2000, American Beauty debuted strongly in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, markets traditionally "not receptive to this kind of upscale fare". The impressive South Korean performance continued, with a return of $1.2 million after nine days.[172] In total, American Beauty grossed $130.1 million in North America and $226.2 million internationally, for $356.3 million worldwide.[160]

Home media

American Beauty was released on VHS on May 9, 2000,[173] and on DVD with the DTS format on October 24, 2000.[174] Before the North American rental release on May 9,[175] Blockbuster Video wanted to purchase hundreds of thousands of extra copies for its "guaranteed title" range, whereby anyone who wanted to rent the film would be guaranteed a copy. Blockbuster and DreamWorks could not agree on a profit-sharing deal, so Blockbuster ordered two-thirds the number of copies it originally intended.[176] DreamWorks made around one million copies available for rental; Blockbuster's share would usually have been about 400,000 of these. Some Blockbuster stores only displayed 60 copies,[177] and others did not display the film at all, forcing customers to ask for it.[176][177] The strategy required staff to read a statement to customers explaining the situation; Blockbuster claimed it was only "[monitoring] customer demand" due to the reduced availability.[176] Blockbuster's strategy leaked before May 9, leading to a 30 percent order increase from other retailers.[175][176] In its first week of rental release, American Beauty made $6.8 million. This return was lower than would have been expected had DreamWorks and Blockbuster reached an agreement. In the same year, The Sixth Sense made $22 million, while Fight Club made $8.1 million, though the latter's North American theatrical performance was just 29 percent that of American Beauty. Blockbuster's strategy also affected rental fees; American Beauty averaged $3.12, compared with $3.40 for films that Blockbuster fully promoted. Only 53 percent of the film's rentals were from large outlets in the first week, compared with the usual 65 percent.[176]

The DVD release included a behind-the-scenes featurette, film audio commentary from Mendes and Ball, and a storyboard presentation with discussion from Mendes and Hall.[174] In the film commentary, Mendes refers to deleted scenes he intended to include in the release.[178] However, these scenes are not on the DVD, as he changed his mind after recording the commentary;[179] Mendes felt that to show scenes he previously chose not to use would detract from the film's integrity.[180]

On September 21, 2010, Paramount Home Entertainment released American Beauty on Blu-ray, as part of Paramount's Sapphire Series. All the extras from the DVD release were present, with the theatrical trailers upgraded to HD.[181]

Critical reception and legacy

Contemporary

American Beauty was widely considered the best film of 1999 by the American press. It received overwhelming praise, chiefly for Spacey, Mendes and Ball.[182] Variety reported that "no other 1999 movie has benefited from such universal raves."[183] It was the best-received title at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF),[154] where it won the People's Choice award after a ballot of the festival's audiences.[184] TIFF's director, Piers Handling, said, "American Beauty was the buzz of the festival, the film most talked-about."[185]

Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 87% of 190 critics gave the film a positive review, with an average rating of 8.2/10. The website's critics' consensus reads: "Flawlessly cast and brimming with dark, acid wit, American Beauty is a smart, provocative high point of late '90s mainstream Hollywood film."[186] According to Metacritic, which assigned a weighted average score of 84 out of 100 based on 34 critics, the film received "universal acclaim".[187]

Writing in Variety, Todd McCarthy said the cast ensemble "could not be better"; he praised Spacey's "handling of innuendo, subtle sarcasm, and blunt talk" and the way he imbued Lester with "genuine feeling".[188] Janet Maslin in The New York Times said Spacey was at his "wittiest and most agile" to date,[189]. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, who awarded the film four out of four stars, singled Spacey out for successfully portraying a man who "does reckless and foolish things [but who] doesn't deceive himself".[190] Kevin Jackson of Sight & Sound said Spacey impressed in ways distinct from his previous performances, the most satisfying aspect being his portrayal of "both sap and hero".[120]

Writing in Film Quarterly, Gary Hentzi praised the actors,[191] but said that characters such as Carolyn and Col. Fitts were stereotypes.[192] Hentzi accused Mendes and Ball of identifying too readily with Jane and Ricky, saying the latter was their "fantasy figure"—a teenaged boy who's an absurdly wealthy artist able to "finance [his] own projects".[193] Hentzi said Angela was the most believable teenager, in particular with her "painfully familiar" attempts to "live up to an unworthy image of herself".[182] Maslin agreed that some characters were unoriginal, but said their detailed characterizations made them memorable.[189]

Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times said the actors coped "faultlessly" with what were difficult roles; he called Spacey's performance "the energy that drives the film", saying the actor commanded audience involvement despite Lester not always being sympathetic. "Against considerable odds, we do like [these characters]," Turan concluded. He stated that the film was layered, subversive, complex, and surprising, concluding it was "a hell of a picture".[194]

Maslin felt that Mendes directed with "terrific visual flair", saying his minimalist style balanced "the mordant and bright" and that he evoked the "delicate, eroticized power-playing vignettes" of his theater work.[189] Jackson said Mendes' theatrical roots rarely showed, and that the "most remarkable" aspect was that Spacey's performance did not overshadow the film. He said that Mendes worked the script's intricacies smoothly, to the ensemble's strengths, and staged the tonal shifts skillfully.[120] McCarthy believed American Beauty a "stunning card of introduction" for film débutantes Mendes and Ball. He said Mendes' "sure hand" was "as precise and controlled" as his theater work. McCarthy cited Hall's involvement as fortunate for Mendes, as the cinematographer was "unsurpassed" at conveying the themes of a work.[188] Turan agreed that Mendes' choice of collaborators was "shrewd", naming Hall and Newman in particular. Turan suggested that American Beauty may have benefited from Mendes' inexperience, as his "anything's possible daring" made him attempt beats that more seasoned directors might have avoided. Turan felt that Mendes' accomplishment was to "capture and enhance [the] duality" of Ball's script—the simultaneously "caricatured ... and painfully real" characters.[194] Hentzi, while critical of many of Mendes and Ball's choices, admitted the film showed off their "considerable talents".[191]

Turan cited Ball's lack of constraint when writing the film as the reason for its uniqueness, in particular the script's subtle changes in tone.[194] McCarthy said the script was "as fresh and distinctive" as any of its American film contemporaries, and praised how it analyzed the characters while not compromising narrative pace. He called Ball's dialogue "tart" and said the characters—Carolyn excepted—were "deeply drawn". One other flaw, McCarthy said, was the revelation of Col. Fitts' homosexuality, which he said evoked "hoary Freudianism".[188] Jackson said the film transcended its clichéd setup to become a "wonderfully resourceful and sombre comedy". He said that even when the film played for sitcom laughs, it did so with "unexpected nuance".[120] Hentzi criticized how the film made a mystery of Lester's murder, believing it manipulative and simply a way of generating suspense.[191] McCarthy cited the production and costume design as pluses, and said the soundtrack was good at creating "ironic counterpoint[s]" to the story.[188] Hentzi concluded that American Beauty was "vital but uneven"; he felt the film's examination of "the ways which teenagers and adults imagine each other's lives" was its best point, and that although Lester and Angela's dynamic was familiar, its romantic irony stood beside "the most enduring literary treatments" of the theme, such as Lolita. Nevertheless, Hentzi believed that the film's themes of materialism and conformity in American suburbia were "hackneyed".[182] McCarthy conceded that the setting was familiar, but said it merely provided the film with a "starting point" from which to tell its "subtle and acutely judged tale".[188] Maslin agreed; she said that while it "takes aim at targets that are none too fresh", and that the theme of nonconformity did not surprise, the film had its own "corrosive novelty".

Retrospective

A few months after the film's release, reports of a backlash appeared in the American press,[195] and the years since have seen its critical regard wane in post-9/11 society and after Spacey's sexual allegations.[196][197] In 2005, Premiere named American Beauty as one of 20 "most overrated movies of all time."[198] Mendes accepted the inevitability of the critical reappraisal, saying in 2008, "I thought some of it was entirely justified—it was a little overpraised at the time."[197]

In 2019, on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the film's release, The Huffington Post's Matthew Jacobs wrote that "the film's reputation has tumbled precipitously," adding, "Plenty of classics undergo cultural reappraisals [...] but few have turned into such a widespread punchline."[3]

In popular culture

The film was spoofed by the animated sitcom Family Guy,[199] the Todd Solondz film Storytelling, the teen movie spoof Not Another Teen Movie, and in the DreamWorks animated film Madagascar.[200]

Accolades

American Beauty was not considered an immediate favorite to dominate the American awards season. Several other contenders opened at the end of 1999, and US critics spread their honors among them when compiling their end-of-year lists.[201] The Chicago Film Critics Association and the Broadcast Film Critics Association named the film the best of 1999, but while the New York Film Critics Circle, the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association recognized American Beauty,[202] they gave their top awards to other films.[201] By the end of the year, reports of a critical backlash suggested American Beauty was the underdog in the race for Best Picture;[195] however, at the Golden Globe Awards in January 2000, American Beauty won Best Film, Best Director and Best Screenplay.[202]

As the nominations for the 72nd Academy Awards approached, a frontrunner had not emerged.[201] DreamWorks had launched a major campaign for American Beauty five weeks before ballots were due to be sent to the 5,600 Academy Award voters. Its campaign combined traditional advertising and publicity with more focused strategies. Although direct mail campaigning was prohibited, DreamWorks reached voters by promoting the film in "casual, comfortable settings" in voters' communities. The studio's candidate for Best Picture the previous year, Saving Private Ryan, lost to Shakespeare in Love, so the studio took a new approach by hiring outsiders to provide input for the campaign. It hired three veteran consultants, who told the studio to "think small". Nancy Willen encouraged DreamWorks to produce a special about the making of American Beauty, to set up displays of the film in the communities' bookstores, and to arrange a question-and-answer session with Mendes for the British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Dale Olson advised the studio to advertise in free publications that circulated in Beverly Hills—home to many voters—in addition to major newspapers. Olson arranged to screen American Beauty to about 1,000 members of the Actors Fund of America, as many participating actors were also voters. Bruce Feldman took writer Alan Ball to the Santa Barbara International Film Festival, where Ball attended a private dinner in honor of Anthony Hopkins, meeting several voters who were in attendance.[203]

In February 2000, American Beauty was nominated for eight Academy Awards; its closest rivals, The Cider House Rules and The Insider, received seven nominations each. In March 2000, the major industry labor organizations[nb 18] all awarded their top honors to American Beauty; perceptions had shifted—the film was now the favorite to dominate the Academy Awards.[201] American Beauty's closest rival for Best Picture was still The Cider House Rules, from Miramax. Both studios mounted aggressive campaigns; DreamWorks bought 38 percent more advertising space in Variety than Miramax.[204] On March 26, 2000, American Beauty won five Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Spacey), Best Original Screenplay and Best Cinematography.[205][nb 19] At the 53rd British Academy Film Awards, American Beauty won six of the 14 awards for which it was nominated: Best Film, Best Actor, Best Actress (Bening), Best Cinematography, Best Film Music and Best Editing.[202] In 2000, the Publicists Guild of America recognized DreamWorks for the best film publicity campaign.[207]

In 2006, the Writers Guild of America ranked the screenplay number 38 on its list of the 101 greatest screenplays.[208]

References

Annotations

- Some postmodernist readings would posit no need for an identified voice; see Death of the Author.

- Despite their desire to conform, Jim and Jim are openly, proudly gay, a contradiction that Sally R. Munt says may seem strange to heterosexual audiences.[24]

- According to Hausmann, "These films appear to suggest that [the film theorist] Kaja Silverman's wish 'that the typical male subject, like his female counterpart, might learn to live with lack'—namely, the 'lack of being' that remains 'the irreducible condition of subjectivity'—has not yet been fulfilled."[45] See Silverman, Kaja (1992). Male Subjectivity at the Margins (New York: Routledge): 65+20. ISBN 9780415904193.

- Kramer uses the analogy of looking at a sculpture: "We determine for ourselves the pacing of our experience: we are free to walk around the piece, view it from many angles, concentrate on some details, see other details in relationship to each other, step back and view the whole, see the relationship between the piece and the space in which we see it, leave the room when we wish close our eyes and remember, and return for further viewings."[57]

- Another example comes with the songs that Carolyn picks to accompany the Burnhams' dinners—upbeat "elevator music" which is later replaced with more discordant tunes that reflect the "escalating tension" at the table. When Jane plays "Cancer for the Cure", she switches off after a few moments because her parents return home. The moment reinforces her as someone whose voice is "cut short", as does her lack of association with as clearly defined genres as her parents.[63]

- At that point called American Rose.[65]

- Ball said he decided on DreamWorks after an accidental meeting with Spielberg in the Amblin Entertainment parking lot, where the writer became confident that Spielberg "got" the script and its intended tone.[70]

- Mendes had considered the idea before; he almost took on The Wings of the Dove (1997) and had previously failed to secure financing for an adaptation of the play The Rise and Fall of Little Voice, which he directed in 1992. The play made it to the screen in 1998 as Little Voice, without Mendes' involvement.[78]

- One of which director of photography Conrad Hall had filmed for Divorce American Style (1967).[127]

- The shot references a similar one in Ordinary People (1980). Mendes included several such homages to other films; family photographs in the characters' homes were inserted to give them a sense of history, but also as a nod to the way Terrence Malick used still photographs in Badlands (1973).[105] A shot of Lester's jogging was a homage to Marathon Man (1976) and Mendes watched several films to help improve his ability to evoke a "heightened sense of style": The King of Comedy (1983), All That Jazz (1979) and Rosemary's Baby (1968).[129]

- The scene at the fast food outlet where Lester discovers Carolyn's affair.[107]

- The navel pictured is not Mena Suvari's; it belongs to the model Chloe Hunter.[150]

- The hand on the poster belongs to actress Christina Hendricks, who was a hand model at the time.[151]

- Mendes said, "So at the end of the film I got up, and I was terribly British, I said, 'So, who kind of liked the movie?' And about a third of them put up their hands, and I thought, 'Oh shit.' So I said, 'OK, who kind of didn't like it?' Two people. And I said, 'Well, what else is there?' And a guy in the front said, 'Ask who really liked the movie.' So I did, and they all put up their hands. And I thought, 'Thank you, God.'"[132]

- "Theaters" refers to individual movie theaters, which may have multiple auditoriums. Later, "screens" refers to single auditoriums.

- Crossing the 600-theater threshold.

- According to the firm, men under 21 gave American Beauty an "A+" grade; women under 21 gave it an "A". Men in the 21–34 age group gave the film a "B+"; women 21–34 gave it an "A−". Men 35 and over awarded a "B+"; women 35 and over gave a "B".[161]

- The Writers Guild of America, the Screen Actors Guild, the Producers Guild of America, the American Society of Cinematographers, and the Directors Guild of America[201]

- The Best Director award was presented to Mendes by Spielberg.[206]

Footnotes

- "American Beauty". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- "American Beauty (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- Jacobs, Matthew (September 9, 2019). "The Steady Cultural Demise Of 'American Beauty'". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on September 10, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- Zacharek, Stephanie. "American Beauty Was Bad 20 Years Ago and It's Bad Now. But It Still Has Something to Tell Us". Time (magazine). Time. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- Booth 2002, p. 129

- Hall 2006, p. 23

- Booth 2002, p. 126

- Booth 2002, p. 128

- Booth 2002, pp. 126–128

- Mendes & Ball 2000, chapter 1

- Anker 2004, pp. 348–349

- Hausmann 2004, p. 118

- Pennington 2007, p. 104

- Munt 2006, pp. 264–265

- Mendes & Ball 2000, chapter 8

- Hausmann 2004, pp. 118–119