Black Indians in the United States

Black Indians are Native American people – defined as Native American due to being affiliated with Native American communities and being culturally Native American – who also have significant African American heritage.[3]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| True population unknown, 269,421 identified as ethnically mixed with African and Native American on 2010 census[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (especially the Southern United States or in locations populated by Southern descendants), Oklahoma, New York and Massachusetts). | |

| Languages | |

| American English, Louisiana Creole, Gullah, Native American languages (including Navajo, Dakota, Cherokee, Choctaw, Mvskoke, Ojibwe)[2], African languages | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Native Americans in the United States |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

|

Historically, certain Native American tribes have had close relations with African Americans, especially in regions where slavery was prevalent or where free people of color have historically resided. Members of the Five Civilized Tribes participated in holding enslaved African Americans in the Southeast and some enslaved or formerly enslaved people migrated with them to the West on the Trail of Tears in 1830 and later during the period of Indian Removal.

In controversial actions, since the late 20th century, the Cherokee, Creek and Seminole nations tightened their rules for membership and at times excluded Freedmen who did not have at least one ancestor listed as Native American on the early 20th-century Dawes Rolls. This exclusion was later appealed in the courts, both because of the treaty conditions and in some cases because of possible inaccuracies in some of the Rolls. The Chickasaw Nation never extended citizenship to Chickasaw Freedmen.[4]

Overview

Until recently, historic relations between Native Americans and African Americans were relatively neglected in mainstream United States history studies.[5] At various times, Africans had varying degrees of contact with Native Americans, although they did not live together in as great number as with Europeans. Enslaved Africans brought to the United States and their descendants have had a history of cultural exchange and intermarriage with Native Americans, as well as with other enslaved mixed-race persons who had some Native American and European ancestry.[6]

Most interaction took place in New England where contact was early[7][8] and the Southern United States, where the largest number of African-descended people were enslaved.[6] In the 21st century, a significant number of African Americans have some Native American ancestry, but most have not grown up within those cultures and do not have current social, cultural or linguistic ties to Native peoples.[9]

Relationships among different Native Americans, Africans, and African Americans have been varied and complex. Some tribes or bands were more accepting of ethnic Africans than others and welcomed them as full members of their respective cultures and communities. Native peoples often disagreed about the role of ethnic African people in their communities. Other Native Americans saw uses for slavery and did not oppose it for others. Some Native Americans and people of African descent fought alongside one another in armed struggles of resistance against U.S. expansion into Native territories, as in the Seminole Wars in Florida.

After the American Civil War, some African Americans became or continued as members of the US Army. Many were assigned to fight against Native Americans in the wars in the Western frontier states. Their military units became known as the Buffalo Soldiers, a nickname given by Native Americans. Black Seminole men in particular were recruited from Indian Territory to work as Native American scouts for the Army.

History

European colonization of the Americas

Records of contacts between Africans and Native Americans date to April 1502, when the first enslaved African arrived in Hispaniola. Some Africans escaped inland from the colony of Santo Domingo; those who survived and joined with the Native tribes became the first group of Black Indians.[10][11] In the lands which later became part of the United States, the first recorded example of an enslaved African escaping from European colonists and being absorbed by Native Americans dates to 1526. In June of that year, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón established a Spanish colony near the mouth of the Pee Dee River in present-day South Carolina. The Spanish settlement was named San Miguel de Guadalupe; its inhabitants included 100 enslaved Africans. In 1526 the first enslaved African fled the colony and took refuge with local Native Americans.[11]

In 1534 Pueblo peoples of the Southwest had contact with the Moroccan slave Esteban de Dorantes before any contact with the remainder of survivors of his Spanish expedition. As part of the Spanish Pánfilo de Narváez expedition, Esteban traveled from Florida in 1528 to what is now New Mexico in 1539, with a few other survivors. He is thought have been killed by Zuni.[12] More than a century later, when the Pueblos united to rid their homelands of the Spanish colonists during the 1690 Pueblo Revolt, one of the organizers of the revolt, Domingo Naranjo (c. 1644 – c. 1696) was a Santa Clara Pueblo man of African ancestry.[13][14]

In 1622 Algonquian Native Americans attacked the colony of Jamestown in Virginia. They massacred all the Europeans but brought some of the few enslaved Africans as captives back to their own communities, gradually assimilating them.[15] Interracial relationships continued to take place between Africans (and later African Americans) and members of Native American tribes in the coastal states. Although the colonists tried to enslave Native Americans in the early years, they abandoned the practise in the early 18th century.[16] Several colonial advertisements for runaway slaves made direct reference to the connections which Africans had in Native American communities. "Reward notices in colonial newspapers now told of African slaves who 'ran off with his Indian wife' or 'had kin among the Indians' or is 'part-Indian and speaks their language good'."[17][18]

Several of the Thirteen Colonies passed laws prohibiting the transportation of enslaved people into the frontier of the Cherokee Nation's territory to restrict interactions between the two groups.[19] European colonists told the Cherokee that the smallpox epidemic of 1739 in the Southeast was due to disease brought by enslaved African.[19] Some tribes encouraged intermarriage with Africans, with the idea that stronger children would result from the unions.[20]

Colonists in South Carolina felt so concerned about the possible threat posed by the mixed African and Native American population that they passed a law in 1725 prohibiting taking enslaved people to the frontier regions, and imposing a fine of 200 pounds if violated. In 1751, South Carolina passed a law against holding Africans in proximity to Native Americans, as the planters considered that detrimental to the security of the colony. Under Governor James Glen (in office 1743–1756), South Carolina promoted an official policy that aimed to create in Native Americans an "aversion" to African Americans in an attempt to thwart possible alliances between them.[21][22]

In 1753, during the chaos of Pontiac's War, a resident of Detroit observed that the Native tribes revolting were killing any whites they came across but were "saving and caressing all the Negroes they take."[15] The resident expressed fear that this practice could eventually lead to a uprising amongst the enslaved people.[15] Similarly, Iroquois chief Thayendanegea, more commonly known as Joseph Brant, similarly welcomed runaway slaves and encouraged them to intermarry in the tribe.[15] Native American adoptions system did not discriminate on the basis of color, and Indian villages would eventually serve as stations on the Underground Railroad.

Historian Carter G. Woodson believed that relations with Native American tribes could have provided an escape hatch from slavery: Native American villages welcomed fugitive slaves and, in the antebellum years, some served as stations on the Underground Railroad.[15]

There were varieties of attitude: some Native Americans resented the presence of Africans.[24] In one account, the "Catawaba tribe in 1752 showed great anger and bitter resentment when an African American came among them as a trader."[24]

European and European-American colonists tried to divide Native Americans and African Americans against each other.[19] Europeans considered both races inferior and tried to convince Native Americans that Africans worked against their best interests.[25][26]

In the colonial period, Native Americans received rewards if they returned formerly enslaved people who had escaped . In the latter 19th century, African-American soldiers had assignments to fight with U.S. forces in Indian Wars in the West.[26][27][28]

European enslavement

European colonists created a new demand market for captives of raids when they founded what would go on to become the Thirteen Colonies.[29][30][31] Especially in the southern colonies, initially developed for resource exploitation rather than settlement, colonists purchased or captured Native Americans to be used as forced labor in cultivating tobacco, and, by the 18th century, rice and indigo.[29][30]

To acquire trade goods, Native Americans began selling war captives to whites rather than integrating them into their own societies.[29][32] Traded goods, such as axes, bronze kettles, Caribbean rum, European jewelry, needles, and scissors, varied among the tribes, but the most prized were rifles.[32] The English copied the Spanish and Portuguese: they saw the enslavement of Africans and Native Americans as a moral, legal, and socially acceptable institution; a common rationale for enslavement was the taking of captives after a "just war" and using slavery as an alternative to a death sentence.[33]

The escape of Native American slaves was frequent, because they had a better understanding of the land, which African slaves did not. Consequently, the Natives who were captured and sold into slavery were often sent to the West Indies, or far away from their traditional homeland.[29]

The oldest known record of a permanent Native American slave was a native man from Massachusetts in 1636.[34] By 1661 slavery had become legal in all of the thirteen colonies.[34] Virginia would later declare "Indians, Mulattos, and Negros to be real estate", and in 1682 New York forbade African or Native American slaves from leaving their master's home or plantation without permission.[34] European colonists also viewed the enslavement of Native Americans differently than the enslavement of Africans in some cases; a belief that Africans were "brutish people" was dominant. While both Native Americans and Africans were considered savages, Native Americans were romanticized as noble people that could be elevated into Christian civilization.[33]

It is estimated that Carolina traders operating out of Charles Town exported an estimated 30,000 to 51,000 Native American captives between 1670 and 1715 in a profitable slave trade with the Caribbean, Spanish Hispaniola, and the Northern colonies.[30][35] It was more profitable to have Native American slaves because African slaves had to be shipped and purchased, while native slaves could be captured and immediately taken to plantations; whites in the Northern colonies sometimes preferred Native American slaves, especially Native women and children, to Africans because Native American women were agriculturalist and children could be trained more easily.[29]

However, Carolinians had more of a preference for African slaves but also capitalized on the Indian slave trade combining both.[36] By the late 1700s records of slaves mixed with African and Native American heritage were recorded.[37] In the eastern colonies it became common practice to enslave Native American women and African men with a parallel growth of enslavement for both Africans and Native Americans.[36] This practice also lead to large number of unions between Africans and Native Americans.[38] This practice of combining African slave men and Native American women was especially common in South Carolina.[36]

During this time records also show that many Native American women bought African men but, unknown to the European traders, the women freed and married the men into their tribe.[26] The Indian wars of the early 18th century, combined with the growing availability of African slaves, essentially ended the Indian Slave trade by 1750.[30] Numerous colonial slave traders had been killed in the fighting, and the remaining Native American groups banded together, more determined to face the Europeans from a position of strength rather than be enslaved.[30][29][36]

Though the Indian Slave Trade ended the practice of enslaving Native Americans continued, records from June 28, 1771, show Native American children were kept as slaves in Long Island, New York.[37] Native Americans had also married while enslaved creating families both native and some of partial African descent.[34] Occasional mentioning of Native American slaves running away, being bought, or sold along with Africans in newspapers is found throughout the later colonial period.[36][37] There are also many accounts of former slaves mentioning having a parent or grandparent who was Native American or of partial descent.[38]

Advertisements asked for the return of both African American and Native American slaves. Records and slave narratives obtained by the WPA (Works Progress Administration) clearly indicate that the enslavement of Native Americans continued in the 1800s mostly through kidnappings.[38] The abductions showed that even in the 1800s little distinction was still made between African Americans and Native Americans.[38] Both Native American and African-American slaves were at risk of sexual abuse by slaveholders and other white men of power.[39][40]

During the transitional period of Africans' becoming the primary race enslaved, Native Americans had been sometimes enslaved at the same time. Africans and Native Americans worked together, lived together in communal quarters, along with white indentured servants, produced collective recipes for food, and shared herbal remedies, myths and legends.[34][41] Some intermarried and had mixed-race children.[34][41] The exact number of Native Americans who were enslaved is unknown because vital statistics and census reports were at best infrequent.[29][37] Andrés Reséndez estimates that between 147,000 and 340,000 Native Americans were enslaved in North America, excluding Mexico.[42]

Among the Cherokee, interracial marriages or unions increased as the number of slaves held by the tribe increased.[19] The Cherokee had a reputation for having slaves work side by side with their owners.[19] The Cherokee resistance to the Euro-American system of chattel slavery created tensions between them and European Americans.[19] The Cherokee tribe began to become divided; as intermarriage between white men and native women increased and there was increased adoption of European culture, so did racial discrimination against those of African-Cherokee blood and against African slaves.[19] Cultural assimilation among the tribes, particularly the Cherokee, created pressure to be accepted by European Americans.[19]

After Indian slavery was ended in the colonies, some African men chose Native American women as their partners because their children would be born free. Beginning from 1662 in Virginia, and soon followed by other colonies, they had established a law, known as partus sequitur ventrem, that said a child's status followed that of the mother. Separately, according to the matrilineal system among many Native American tribes, children were considered to be born to and to belong to the mother's people, so were raised as Native American. As European expansion increased in the Southeast, African and Native American marriages became more common.[26]

1800s through the Civil War

In the early 19th century, the US government believed that some tribes had become extinct, especially on the East Coast, where there had been a longer period of European settlement, and where most Native Americans had lost their communal land. Few reservations had been established and they were considered landless.[43] At that time, the government did not have a separate census designation for Native Americans. Those who remained among the European-American communities were frequently listed as mulatto, a term applied to Native American-white, Native American-African, and African-white mixed-race people, as well as tri-racial people.[43]

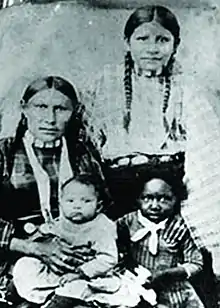

The Seminole people of Florida formed in the 18th century, in what is called ethnogenesis, from Muscogee (Creek) and Florida tribes. They incorporated some Africans who had escaped from slavery. Other maroons formed separate communities near the Seminole, and were allied with them in military actions. Much intermarriage took place. African Americans living near the Seminole were called Black Seminole. Several hundred people of African descent traveled with the Seminole when they were removed to Indian Territory. Others stayed with the few hundred Seminole who remained in Florida, undefeated by the Americans.

By contrast, an 1835 census of the Cherokee showed that 10% were of African descent.[18] In those years, censuses of the tribes classified people of mixed Native American and African descent as "Native American".[44] But during the registration of tribal members for the Dawes Rolls, which preceded land allotment by individual heads of household of the tribes, generally Cherokee Freedmen were classified separately on a Freedmen roll. Registrars often worked quickly, judging by appearance, without asking if the freedmen had Cherokee ancestry, which would have qualified them as "Cherokee by blood" and listing on those rolls.[15]

This issue has caused problems for their descendants in the late 20th and 21st century. The nation passed legislation and a constitutional amendment to make membership more restrictive, open only to those with certificates of blood ancestry (CDIB), with proven descent from "Cherokee by blood" individuals on the Dawes Rolls. Western frontier artist George Catlin described "Negro and North American Indian, mixed, of equal blood" and stated they were "the finest built and most powerful men I have ever yet seen."[15] By 1922 John Swanton's survey of the Five Civilized Tribes noted that half the Cherokee Nation consisted of Freedmen and their descendants.

Former slaves and Native Americans intermarried in northern states as well. Massachusetts Vital Records prior to 1850 included notes of "Marriages of 'negroes' to Indians". By 1860 in some areas of the South, where race was considered binary of black (mostly enslaved) or white, white legislators thought the Native Americans no longer qualified as "Native American," as many were mixed and part black. They did not recognized that many mixed-race Native Americans identified as Indian by culture and family. Legislators wanted to revoke the Native American tax exemptions.[15]

Freed African Americans, Black Indians, and Native Americans fought in the American Civil War against the Confederate Army. During November 1861, the Muscogee Creek and Black Indians, led by Creek Chief Opothleyahola, fought three pitched battles against Confederate whites and allied Native Americans to reach Union lines in Kansas and offer their services.[15] Some Black Indians served in colored regiments with other African-American soldiers.[45]

Black Indians were documented in the following regiments: The 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, the Kansas Colored at Honey Springs, the 79th US Colored Infantry, and the 83rd US Colored Infantry, along with other colored regiments that included men listed as Negro.[45] Some Civil War battles occurred in Indian Territory.[46] The first battle in Indian Territory took place July 1 and 2 in 1863, and Union forces included the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry.[46] The first battle against the Confederacy outside Indian Territory occurred at Horse Head Creek, Arkansas on February 17, 1864. The 79th US Colored Infantry participated.[46]

Many Black Indians returned to Indian Territory after the Civil War had been won by the Union.[45] When the Confederacy and its Native American allies were defeated, the US required new peace treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes, requiring them to emancipate slaves and make those who chose to stay with the tribes full citizens of their nations, with equal rights in annuities and land allotments. The former slaves were called "Freedmen," as in Cherokee Freedmen, Chickasaw Freedmen, Choctaw Freedmen, Creek Freedmen and Seminole Freedmen. The pro-Union branch of the Cherokee government had freed their slaves in 1863, before the end of the war, but the pro-Confederacy Cherokee held their slaves until forced to emancipate them.[15][47]

Native American slave ownership

Slavery had existed among Native Americans, as a way to make use of war captives, before it was introduced by the Europeans. It was not the same as the European style of chattel slavery, in which slaves were counted as the personal property of a master. In Cherokee oral tradition, they enslaved war captives and it was a temporary status pending adoption into a family and clan, or release.[48]

As the United States Constitution and the laws of several states permitted slavery after the American Revolution (while northern states prohibited it), Native Americans were legally allowed to own slaves, including those brought from Africa by Europeans. In the 1790s, Benjamin Hawkins was the federal agent assigned to the southeastern tribes. Promoting assimilation to European-American mores, he advised the tribes to take up slaveholding so that they could undertake farming and plantations as did other Americans.[19] The Cherokee tribe had the most members who held black slaves, more than any other Native American nation.[49]

Records from the slavery period show several cases of brutal Native American treatment of black slaves. However, most Native American masters rejected the worst features of Southern practices.[15] Federal Agent Hawkins considered the form of slavery as practiced by the Southern tribes to be inefficient because the majority didn't practice chattel slavery.[19] Travelers reported enslaved Africans "in as good circumstances as their masters". A white Indian Agent, Douglas Cooper, upset by the Native American failure to practice more severe rules, insisted that Native Americans invite white men to live in their villages and "control matters".[15]

Though less than 3% of Native Americans owned slaves, the fact of a racial caste system and bondage, and pressure from European-American culture, created destructive cleavages in their villages. Some already had a class hierarchy based on "white blood", in part because Native Americans of mixed race sometimes had stronger networks with traders for goods they wanted.[15] Among some bands, Native Americans of mixed white blood stood at the top, pure Native Americans next, and people of African descent were at the bottom.[15] Some of the status of partial white descent may have been related to the economic and social capital passed on by white relations.

Members of Native groups held numerous African-American slaves through the Civil War. Some of these slaves later recounted their lives for a WPA oral history project during the Great Depression in the 1930s.[50]

Native American Freedmen

After the Civil War, in 1866 the United States government required new treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes, who each had major factions allied with the Confederacy. They were required to emancipate their slaves and grant them citizenship and membership in the respective tribes, as the United States freed slaves and granted them citizenship by amendments to the US Constitution. These people were known as "Freedmen," for instance, Muscogee or Cherokee Freedmen.[52]

Similarly, the Cherokee were required to reinstate membership for the Delaware, who had earlier been given land on their reservation, but fought for the Union during the war.[52] Many of the Freedmen played active political roles in their tribal nations over the ensuing decades, including roles as interpreters and negotiators with the federal government. African Muscogee men, such as Harry Island and Silas Jefferson, helped secure land for their people when the government decided to make individual allotments to tribal members under the Dawes Act.

Some Maroon communities allied with the Seminole in Florida and intermarried. The Black Seminole included those with and without Native American ancestry.

When the Cherokee Nation drafted its constitution in 1975, enrollment was limited to descendants of people listed on the Dawes "Cherokee By Blood" rolls. On the Dawes Rolls, US government agents had classified people as Cherokee by blood, intermarried whites, and Cherokee Freedmen, regardless of whether the latter had Cherokee ancestry qualifying them as Cherokee by blood. The Shawnee and Delaware gained their own federal recognition as the Delaware Tribe of Indians and the Shawnee Tribe. A political struggle over this issue has ensued since the 1970s. Cherokee Freedmen have taken cases to the Cherokee Supreme Court. The Cherokee later reinstated the rights of Delaware to be considered members of the Cherokee, but opposed their bid for independent federal recognition.[52]

The Cherokee Nation Supreme Court ruled in March 2006 that Cherokee Freedmen were eligible for tribal enrollment. In 2007, leaders of the Cherokee Nation held a special election to amend their constitution to restrict requirements for citizenship in the tribe. The referendum established direct Cherokee ancestry as a requirement. The measure passed in March 2007, thereby forcing out Cherokee Freedmen and their descendants unless they also had documented, direct "Cherokee by blood" ancestry. This has caused much controversy.[53] The tribe has determined to limit membership only to those who can demonstrate Native American descent based on listing on the Dawes Rolls.[54]

Similarly, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma moved to exclude Seminole Freedmen from membership. In 1990 it received $56 million from the US government as reparations for lands taken in Florida. Because the judgment trust was based on tribal membership as of 1823, it excluded Seminole Freedmen, as well as Black Seminoles who held land next to Seminole communities. In 2000 the Seminole chief moved to formally exclude Black Seminoles unless they could prove descent from a Native American ancestor on the Dawes Rolls. 2,000 Black Seminoles were excluded from the nation.[55] Descendants of Freedmen and Black Seminoles are working to secure their rights.

There's never been any stigma about intermarriage", says Stu Phillips, editor of The Seminole Producer, a local newspaper in central Oklahoma. "You've got Indians marrying whites, Indians marrying blacks. It was never a problem until they got some money.

An advocacy group representing descendants of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes claims that members are entitled to be citizens in both the Seminole and Cherokee nations, as many are indeed part Native American by blood, with records to prove it. Because of racial discrimination, their ancestors were classified and listed incorrectly, under only the category of Freedmen, at the time of the Dawes Rolls. In addition, the group notes that post-Civil War treaties of these tribes with the US government required they give African Americans full citizenship upon emancipation, regardless of blood quantum. In many cases, Native American descent has been difficult for people to trace from historical records.[56] Over 25,000 Freedmen descendants of the Five Civilized Tribes may be affected by the legal controversies.[55]

The Dawes Commission enrollment records, intended to establish rolls of tribal members for land allocation purposes, were done under rushed conditions by a variety of recorders. Many tended to exclude Freedmen from Cherokee rolls and enter them separately, even when they claimed Cherokee descent, had records of it, and had Cherokee physical features. Descendants of Freedmen see the tribe's contemporary reliance on the Dawes Rolls as a racially based way to exclude them from citizenship.[57][58]

Before the Dawes Commission was established,

(t)he majority of the people with African blood living in the Cherokee nation prior to the Civil war lived there as slaves of Cherokee citizens or as free black non-citizens, usually the descendants of Cherokee men and women with African blood ... In 1863, the Cherokee government outlawed slavery through acts of the tribal council. In 1866, a treaty was signed with the US government in which the Cherokee government agreed to give citizenship to those people with African blood living in the Cherokee nations who were not already citizens. African Cherokee people participated as full citizens of that nation, holding office, voting, running businesses, etc.[59]

After the Dawes Commission established tribal rolls, in some cases Freedmen of the Cherokee and the other Five Civilized Tribes were treated more harshly. Degrees of continued acceptance into tribal structures were low during the ensuing decades. Some tribes restricted membership to those with a documented Native ancestor on the Dawes Commission listings, and many restricted officeholders to those of direct Native American ancestry. In the later 20th century, it was difficult for Black Native Americans to establish official ties with Native groups to which they genetically belonged. Many Freedmen descendants believe that their exclusion from tribal membership, and the resistance to their efforts to gain recognition, are racially motivated and based on the tribe's wanting to preserve the new gambling revenues for fewer people.[52][60]

Genealogy and genetics

African Americans looking to trace their genealogy can face many difficulties. While a number of the Native American nations are better-documented than the white communities of the era,[62] the destruction of family ties and family records during the human trafficking of the Atlantic slave trade has made tracking African American family lines much more difficult. In Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage, William Katz writes that the number of Black Indians among the Native American nations were "understated by hundreds of thousands"; and that by comparing pictorial documentation to verbal and written accounts it is clear that when Black Indians were spotted in these settings, they were often simply not remarked upon or recorded by white chroniclers of the era.[63]

Enslaved Africans were renamed by those who enslaved them, and usually not even recorded with surnames until after the American Civil War. Historical records usually relied upon by genealogists, such as censuses, did not record the names of enslaved African Americans before the Civil war. While some major slavers kept extensive records, which historians and genealogists have used to create family trees, generally researchers find it difficult to trace African American families before the Civil War. Enslaved people were also forbidden to learn to read and write, and harshly punished or even killed if they defied this ban, making records kept by families themselves extremely rare.[5]

Elder family members may have tried to keep an oral history of the family, but due to these many difficulties, these accounts have not always been as reliable as hoped for. Knowing the family's geographic origins may help individuals know where to start in piecing together their genealogy.[5] Working from oral history and what records exist, descendants can try to confirm stories of more precise African origins, and any possible Native ancestry through genealogical research and even DNA testing. However, DNA cannot reliably indicate Native American ancestry, and no DNA test can indicate tribal origin.[64][65][66]

DNA testing and research has provided some data about the extent of Native American ancestry among African Americans, which varies in the general population. Based on the work of geneticists, Harvard University historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr. hosted a popular, and at times controversial, PBS series, African American Lives, in which geneticists said DNA evidence shows that Native American ancestry is far less common among African Americans than previously believed.[67]

Their conclusions were that while almost all African Americans are racially mixed, and many have family stories of Native heritage, usually these stories turn out to be inaccurate,[68][69][70] with only 5 percent of African American people showing more than 2 percent Native American ancestry.[68] Gates summarized these statistics to mean that, "If you have 2 percent Native American ancestry, you had one such ancestor on your family tree five to nine generations back (150 to 270 years ago)."[68] Their findings also concluded that the most common "non-Black" mix among African Americans is English and Scots-Irish.[70] Some critics thought the PBS series did not sufficiently explain the limitations of DNA testing for assessment of heritage.[71]

Another study, published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, also indicated that, despite how common these family stories are, relatively few African-Americans who have these stories actually turned out to have detectable Native American ancestry.[72] A study reported in the American Journal of Human Genetics stated, "We analyzed the European genetic contribution to 10 populations of African descent in the United States (Maywood, Illinois; Detroit; New York; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh; Baltimore; Charleston, South Carolina; New Orleans; and Houston) ... mtDNA haplogroups analysis shows no evidence of a significant maternal Amerindian contribution to any of the 10 populations."[73] Despite this, some still insist that most African Americans have at least some Native American heritage.[74] Henry Louis Gates, Jr. wrote in 2009,

Here are the facts: Only 5 percent of all black Americans have at least 12.5 percent Native American ancestry, the equivalent of at least one great-grandparent. Those 'high cheek bones' and 'straight black hair' your relatives brag about at every family reunion and holiday meal since you were 2 years old? Where did they come from? To paraphrase a well-known French saying, 'Seek the white man.' African Americans, just like our first lady, are a racially mixed or mulatto people—deeply and overwhelmingly so. Fact: Fully 58 percent of African American people, according to geneticist Mark Shriver at Morehouse College, possess at least 12.5 percent European ancestry (again, the equivalent of that one great-grandparent).[75]

Geneticists from Kim Tallbear (Dakota) to The Indigenous Peoples Council on Biocolonialism (IPCB) agree that DNA testing is not how tribal identity is determined, with Tallbear stressing that

People think there is a DNA test to prove you are Native American. There isn't.[64]

and the IPCB noting that

"Native American markers" are not found solely among Native Americans. While they occur more frequently among Native Americans they are also found in people in other parts of the world.[76]

Tallbear also stresses that tribal identity is based in political citizenship, culture, lineage and family ties, not "blood", "race", or genetics.[64][65]

Writing for ScienceDaily, Troy Duster wrote that the two common types of tests used are Y-chromosome and mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) testing. The tests processes for direct-line male and female ancestors. Each follows only one line among many ancestors and thus can fail to identify others.[77][78] Though DNA testing for ancestry is limited, a paper in 2015 posited that ancestries can show different percentages based on the region and sex of one's ancestors. These studies found that on average, people who identified as African American in their sample group had 73.2-82.1% West African, 16.7%-29% European, and 0.8–2% Native American genetic ancestry, with large variation between individuals.[79][80][81][82]

Autosomal DNA testing surveys DNA that has been inherited from parents of an individual.[83] Autosomal tests focus on genetic markers which might be found in Africans, Asians, and people from every other part of the world.[83] DNA testing still cannot determine an individual's full ancestry with absolute certitude.[83]

Notable Black Native Americans

Claims of African American and Native American identity are often disputed. As Sharon P. Holland and Tiya Miles note, "Pernicious cultural definitions of race ... structure this divide, as blackness has been capaciously defined by various state laws according to the legendary one-drop rule, while Indianness has been defined by the US government according to the many buckets rule."[84]

While many US states historically categorized a person as Black if they had even one Black ancestor (the "one drop rule"), Native Americans have been required to meet high blood quantum requirements. For example, the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 only recognized Native people with "one half or more Indian blood". It can sometimes be difficult for Native people to provide paper evidence of their ancestry, especially for Black Native Americans as their mixed race ancestors may have been recorded only as Black. Many tribes today still have blood quantum requirements as part of their criteria for tribal membership.[85]

The list below contains notable individuals with African American ancestry who are tribal citizens or who have been recognized by their communities.

Historic

- William Apess (African-Pequot, 1798–1839), Methodist minister and author.[86][87]

- Crispus Attucks (African-Wampanoag, 1723–1770) dockworker, merchant seaman, an icon in the anti-slavery movement, the first casualty of the Boston Massacre and the American Revolutionary War.[88]

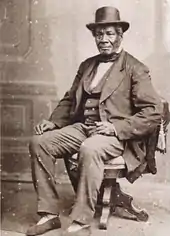

- George Bonga (African-Ojibwe, 1802–1880), fur trader and interpreter in what is now Minnesota, son of trader and interpreter Pierre Bonga.[89]

- Billy Bowlegs III (African-Seminole, 1862–1965)[90]

- Olivia Ward Bush, (Montauk, 1869–1944), author, poet, journalist and tribal historian.[91][92]

- Joseph Louis Cook (Mohawk tribal member of African-Abenaki descent, d. 1814) colonel in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.[93]

- Paul Cuffee (Ashanti/Wampanoag, 1759–1817)[94][95]

- Pompey Factor (African-Seminole, 1849–1928) Black Seminole Scout, Medal of Honor recipient.

- John Horse, Juan Caballo (Black Seminole, 1812–1882), war chief in Florida, also the leader of African-Seminole in Mexico.[96]

- Edmonia Lewis (African-Haitian-Mississauga, c. 1845–1911) sculptor.[97]

- Adam Paine (African-Seminole, 1843–1877) Black Seminole Scout, Medal of Honor recipient.

- Charlie Patton (African-Cherokee descent, 1887–1934), founding father of the blues in the Mississippi Delta.[98]

- Isaac Payne (African-Seminole, 1854–1904) Black Seminole Scout, Medal of Honor recipient.

- Marguerite Scypion (African-Natchez, c. 1770s–after 1836), freedwoman who won her freedom from slavery in court.[99]

- John Ward (Medal of Honor) (African-Seminole, 1847 or 1848–1911) Black Seminole Scout, Medal of Honor recipient.

Contemporary

- Natalie Ball (Klamath/Modoc), born 1980, interdisciplinary artist[100]

- Joe Burton (Soboba Luiseño, basketball player

- Radmilla Cody (Diné), 46th Miss Navajo Nation (1998), traditional singer, enrolled member of the Navajo Nation with African-American ancestry, first bi-racial Miss Navajo, and advocate against domestic violence in both the Navajo Nation and the state of Arizona[101]

- Angel Goodrich (Cherokee Nation), WNBA basketball player for the Tulsa Shock and the Seattle Storm[102]

- Mary Ann Green (Augustine Cahuilla, 1964–2017), chairperson who reestablished the Augustine Cahuilla reservation and tribal government[103]

- Lisa Holt (Cochiti Pueblo), ceramic artist[104]

- Mwalim (Mashpee Wampanoag), musician, writer, and educator[105]

- Harlan Reano (Kewa Pueblo), ceramic artist[104]

- Angel Haze (Cherokee), born 1991, a Two-Spirit rapper and singer[106][107]

- Kyrie Irving (Lakota), born 1992, NBA basketball player[108][109]

- France Winddance Twine (Muscogee (Creek) Nation, born 1960), sociologist[110]

- William S. Yellow Robe Jr. (Assiniboine), playwright and educator[111]

- Nyla Rose (Oneida descent), professional wrestler, martial artist, and actress[112]

- Kelvin Sampson (Lumbee), college basketball coach [113]

- Santiago X, Louisiana Coushatta multidisciplinary artist and architect[114]

- Powtawche Valerino (Mississippi Choctaw), NASA engineer

- Delonte West (Piscataway), retired NBA basketball player [115]

See also

- Black Seminoles

- Creek Freedmen

- Cherokee freedmen controversy

- Dawes Rolls

- Mardi Gras Indians

- Native American name controversy

- One-drop rule

Notes

- "Table 4. Two or More Races Population by Number of Races and Selected Combinations for the United States" (PDF). Census 2010 Quicktables. US Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Siebens, J & T Julian. Native North American Languages Spoken at Home in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2006–2010. United States Census Bureau. December 2011.

- Katz, William Loren (3 January 2012). Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage. Simon and Schuster. p. 5. ISBN 9781442446373. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

I have defined Black Indians as people who have a dual ancestry or black people who have lived for some time with Native Americans (e.g., lived on reservations)

- Reese, Linda. Freedmen. Oklahoma History Center's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Archived from the original on 2013-08-25. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Mary A. Dempsey (1996). "The Indian Connection". American Visions.

- Angela Y. Walton-Raji (2008). "Researching Black Indian Genealogy of the Five Civilized Tribes". Heritage Books. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- Daniel Mandell, "The Saga of Sarah Muckamugg: Indian and African American Intermarriage in Colonial New England," in Martha Hodes, ed. Sex, Love Race: Crossing Boundaries in North American History(New York: New York University Press, 1999), 72-90

- Tiffany McKinney, "Race and Federal Recognition in Native New England," in Tiya Miles and Sharon Holland, eds. Crossing Waters, crossing Worlds: The African Diaspora in Indian Country (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 57-79

- G. Reginald Daniel (2008). More Than Black?: Multiracial. Temple University Press. ISBN 9781439904831. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- Katz, Black Indians, 28.

- Muslims in American History: A Forgotten Legacy by Dr. Jerald F. Dirks. ISBN 1-59008-044-0 Page 204.

- Flint, Richard and Shirley Cushing Flint. "Dorantes, Esteban de". Archived 2012-03-24 at the Wayback Machine New Mexico Office of the State Historian. 10 Aug 2013.

- Jones, Rhett (2003). Conyers, James L. Jr. (ed.). Afrocentricity and the Academy: Essays on Theory and Practice. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. p. 268. ISBN 0-7864-1542-8.

- Afrocentricity and the academy : essays on theory and practice. James L. Conyers. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. 2003. ISBN 0-7864-1542-8. OCLC 51297099.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - William Loren Katz (2008). "Africans and Indians: Only in America". William Loren Katz. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- Angela Y. Walton-Raji (2008). "Tri-Racials: Black Native Americans of the Upper South". Design © 1997. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- Black NDNs. Archived 2013-12-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 10 Aug 2013.

- Katz, Black Indians, p. 103.

- Tiya Miles (2008). Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520250024. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- Nomad Winterhawk (1997). "Black Indians want a place in history". Djembe Magazine. Archived from the original on 2009-07-14. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- Patrick Minges (2003), Slavery in the Cherokee Nation: The Keetoowah Society and the Defining of a People, 1855-1867, Psychology Press, p. 27, ISBN 978-0-415-94586-8

- Kimberley Tolley (2007), Transformations in Schooling: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, Macmillan, p. 228, ISBN 978-1-4039-7404-4

- "Diana Fletcher." Women in History-Ohio. Accessed 18 May 2014.

- Red, White, and Black, p. 99. ISBN 0-8203-0308-9

- Red, White, and Black, p. 105, ISBN 0-8203-0308-9

- Dorothy A. Mays (2004). Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World. ABC-CLIO. p. 214. ISBN 9781851094295.

- Art T. Burton (1996). "Cherokee Slave Revolt of 1842". LWF Communications. Archived from the original on 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- Fay A. Yarbrough (2007). Race and the Cherokee Nation. Univ of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812240566. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- Gallay, Alan (2009). "Introduction: Indian Slavery in Historical Context". In Gallay, Alan (ed.). Indian Slavery in Colonial America. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 1–32. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Lauber, Almon Wheeler (1913). "Indian Slavery in Colonial Times Within the Present Limits of the United States Chapter 1: Enslavement by the Indians Themselves". 53 (3). Columbia University: 25–48.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Katz, William Loren (3 January 2012). Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage. Simon and Schuster. pp. 254. ISBN 9781442446373. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

black indians.

- Snyder (2010), "Indian Slave Trade" [Ch. 2], in Slavery, pp. 46-79.

- Gallay, Alan (2009). "South Carolina's Entrance into the Indian Slave Trade". In Gallay, Alan (ed.). Indian Slavery in Colonial America. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 109–146. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Katz, William Loren (1996). "Their Mixing is to be Prevented". Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage. Atheneum Books For Young Readers. pp. 109–125.

- Krauthamer (2013), "Black Slaves, Indian Masters" [Ch. 1], in Black Slaves, pp. 17–45.

- Bossy, Denise I. (2009). "Indian Slavery in Southeastern Indian and British Societies, 1670–1730". In Gallay, Alan (ed.). Indian Slavery in Colonial America. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 207–250. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Lauber (1913), "The Number of Indian Slaves" [Ch. IV], in Indian Slavery, pp. 105-117.

- Yarbrough, Fay A. (2008). "Indian Slavery and Memory: Interracial sex from the slaves' perspective". Race and the Cherokee Nation. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 112–123.

- Browne-Marshall, Gloria J. (2011) [2002]. "The Realities of Enslaved Female Africans in America". Race, Racism and the Law: Speaking Truth to Power!!. Dayton, OH: University of Dayton, School of Law. Archived from the original on December 11, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Linwood Custalow & Angela L. Daniel (2009). The true story of Pocahontas. Fulcrum Publishing. ISBN 9781555916329. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- National Park Service (2009-05-30). "Park Ethnography: Work, Marriage, Christianity". National Park Service.

- Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The other slavery: The uncovered story of Indian enslavement in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-544-94710-8.

- Angela Y. Walton-Raji (1999). "Tri-Racials: Black Indians of the Upper South". GenealogyToday. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- Knickmeyer, Ellen. "Cherokee Nation To Vote on Expelling Slaves' Descendants", Washington Post, 3 March 2007 (Accessible as of July 13, 2007 here )

- Angela Y. Walton-Raji (2008). "Oklahoma Freedmen in the Civil War". Angela Y. Walton-Raji. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- Angela Y. Walton-Raji (2008). "Battles Fought in Indian Territory: Battles Fought by I.T. Freedmen outside of Indian Territory". Angela Y. Walton-Raji. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- Taylor, Quintard. "Cherokee Emancipation Proclamation (1863)", The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed (retrieved 10 January 2010).

- Russell, Steve (2002). "Apples are the Color of Blood", Critical Sociology, Vol. 28, 1, 2002, p. 70.

- Littlefield, Daniel F. Jr. The Cherokee Freedmen: From Emancipation to American Citizenship, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978, p. 68.

- "Lucinda Davis". www.african-nativeamerican.com.

- Hudson, Charles. The Southeastern Indians, 1976, p. 479.

- "Delaware Tribe of Indians Supports Cherokee Freedmen Treaty Rights" Archived 2006-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, Descendants of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, 2004, accessed 6 October 2009.

- "Cherokees eject slave descendants". BBC News. 2007-03-04. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- "Tulsa World: News".

- Brendan I. Koerner, "Blood Feud", Wired 13.09, accessed 3 June 2008.

- "History" Archived 2006-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, Descendants of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, 2 August 2005, accessed 6 October 2009.

- "Myths" Archived 2006-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, Descendants of Freedmen of the 5 Civilized Tribes, 2 August 2005, accessed 6 October 2009

- "History" Archived 2006-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, Descendants of Freedmen of the 5 Civilized Tribes, 2 August 2005, accessed 6 October 2009.

- Marilyn Vann, "Why: Cherokee Freedmen Story" Archived 2006-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, Descendants of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, 2 August 2005, accessed 6 October 2009.

- William Loren Katz, "Racism and the Cherokee Nation", Final Call.com, 8 April 2007.

- "Czarina Conlan Collection: Photographs". Oklahoma Historical Society Star Archives. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- Cornsilk, David (10 July 2015). "An Open Letter to Defenders of Andrea Smith: Clearing Up Misconceptions about Cherokee Identification". IndianCountryToday.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- Katz, William Loren (3 January 2012). Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage. Simon and Schuster. p. 3. ISBN 9781442446373. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Geddes, Linda (5 February 2014). "'There is no DNA test to prove you're Native American'". New Scientist. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Kimberly Tallbear (2003). "DNA, Blood, and Racializing the Tribe". Wíčazo Ša Review. University of Minnesota Press. 18 (1): 81–107. doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0008. JSTOR 140943. S2CID 201778441.

- Brett Lee Shelton, J. D.; Jonathan Marks (2008). "Genetic Markers Not a Valid Test of Native Identity". Counsel for Responsible Genetics. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- "DNA Testing: review, African American Lives, About.com". Archived from the original on March 13, 2009.

- Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (29 Dec 2014). "High Cheekbones and Straight Black Hair?". The Root. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. On DNA Testing And Finding His Own Roots - Transcript". Fresh Air . 21 Jan 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "DNA Testing: review, African American Lives, About.com". Archived from the original on March 13, 2009.

- Troy Duster (2008). "Deep Roots and Tangled Branches". Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- Esteban Parra; et al. (1998). "Estimating African American Admixture Proportions by Use of Population-Specific Alleles". American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (6): 1839–1851. doi:10.1086/302148. PMC 1377655. PMID 9837836.

- Parra, Esteban J. (1998). "Estimating African American Admixture Proportions by Use of Population". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (6): 1839–1851. doi:10.1086/302148. PMC 1377655. PMID 9837836.

- Sherrel Wheeler Stewart (2008). "More Blacks are Exploring the African-American/Native American Connection". BlackAmericaWeb.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2006. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr., "Michelle's Great-Great-Great-Granddaddy—and Yours." Archived October 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine The Root.com, 8 October 2009. Retrieved 10 Aug 2013.

- Kim TallBear (2008). "Can DNA Determine Who is American Native American?". The WEYANOKE Association. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ScienceDaily (2008). "Genetic Ancestral Testing Cannot Deliver On Its Promise, Study Warns". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- Troy Duster (2008). "Deep Roots and Tangled Branches". Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- Katarzyna Bryc; Adam Auton; Matthew R. Nelson; Jorge R. Oksenberg; Stephen L. Hauser; Scott Williams; Alain Froment; Jean-Marie Bodo; Charles Wambebe; Sarah A. Tishkoff; Carlos D. Bustamante (January 12, 2010). "Genome-wide patterns of population structure and admixture in West Africans and African Americans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (2): 786–791. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107..786B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909559107. PMC 2818934. PMID 20080753.

- Katarzyna Bryc; Eric Y. Durand; J. Michael Macpherson; David Reich; Joanna L. Mountain (January 8, 2015). "The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 96 (1): 37–53. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010. PMC 4289685. PMID 25529636.

- Soheil Baharian; Maxime Barakatt; Christopher R. Gignoux; Suyash Shringarpure; Jacob Errington; William J. Blot; Carlos D. Bustamante; Eimear E. Kenny; Scott M. Williams; Melinda C. Aldrich; Simon Gravel (May 27, 2015). "The Great Migration and African-American Genomic Diversity". PLOS Genetics. 12 (5): e1006059. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006059. PMC 4883799. PMID 27232753.

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr., "Exactly How 'Black' Is Black America?", The Root, February 11, 2013.

- John Hawks (2008). "How African Are You? What genealogical testing can't tell you". Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- Warrior, Robert, ed. (2014). The World of Indigenous North America. Routledge. p. 525.

- Hilleary, Cecily (24 July 2021). "Some Native Americans Fear Blood Quantum is Formula For 'Paper Genocide'". voanews.com.

- Barry O'Connell, ed., A Son of the Forest and Other Writings, University of Massachusetts, 1997, p. 3

- O'Connell, Barry, ed. On Our Own Ground: The Complete Writings of William Apess, a Pequot, N.P.: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992, p. 314

- African American Trail Project - 18th Century at Tufts University. Accessed 5 May 2019

- "George Bonga, an early settler in Minnesota". African American Registry. Archived from the original on 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- Robinson, Jim (April 5, 1998). "Billy Bowlegs III had a name with History". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

Stout, Wesley (March 1, 1965). "Billy Bowlegs Told of How 7 Were Killed". The Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved February 2, 2019. - "Olivia Ward Bush: 1869–1944." New York State Hall of Governors. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- http://easthamptonlibrary.org/wp-content/files/pdfs/history/lectures/19980823.pdf

- Darren Bonaparte, "Louis Cook: A French and Indian Warrior", Wampum Chronicles, 16 September 2005

- Gates, Henry Louis; Root, Jr (4 January 2013). "Paul Cuffee and the First Back-to-Africa Effort - African American History Blog". PBS.

- Kaplan, Sidney; Kaplan, Emma Nogrady (1989). The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution (Rev. ed.). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780870236631.

- Jon D. May (2009). "Horse, John (ca. 1812-1882)". OKState.org/. Oklahoma Historical Society: Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015.

- Edmonia Lewis, Edmonia Lewis. Accessed 2008-01-05.

- Farber, Jim (2017-07-19). "'Buried history': unearthing the influence of Native Americans on rock'n'roll". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- Corbett, Katharine T. (1999). In Her Place: A Guide to St. Louis Women's History. Missouri History Museum. ISBN 9781883982300.

- Steinkopf-Frank, Hannah (10 October 2017). "Existence as Resistance". Herald and News. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- March 7, Leo W. Banks; Now, 2011 From the print edition Like Tweet Email Print Subscribe Donate (7 March 2011). "An Unusual Miss Navajo". www.hcn.org.

- "Native Daughters: Angel Goodrich". UNL College of Journalism and Mass Communications. November 24, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- "Valley Mourns Passing of Mary Ann Green". Greater Coachella Valley Chamber of Commerce. No. 13 January 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Lisa Holt & Harlan Reano". Shumakolowa Native Arts. 19 Pueblo Tribes of New Mexico. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Cooper, Kenneth J. (December 30, 2014). "Black Native Americans beginning to assert identity". Bay State Banner. Dorchester, Boston, Massachusetts. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- Keating, Shannon (March 28, 2015). "The Evolution of Angel Haze". buzzfeed.com.

- Feather, Talking (n.d.). "First Nations Rappers: Keeping Culture: Changing Stereotypes". talking-feather.com.

- Hatton, Faith (August 27, 2021). "Standing Rock Sioux Tribe welcomes NBA player as official member". kfyrtv.com. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- Vardon, Joe (February 3, 2022). "'Who can I trust?': Following Kyrie Irving's footsteps on his ongoing quest to find himself". The Athletic. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- "Curriculum Vitae". Retrieved 26 May 2019

- Morgan-Hubbard, Sage (1 November 2002). "Interview with William S. Yellow Robe, Jr". library.brown.edu. Brown University Library. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Schmidt, Samantha. "In a professional wrestling ring, a transgender woman faces a roaring crowd". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- Championship within reach for Lumbee coach. Indian Country Today. April 2, 2021. Retrieved on November 23, 2021.

- "Artist Santiago X makes his mark". Chicago Tribune. 25 February 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Delonte West Player Mailbox. NBA.com. February 3, 2009. Retrieved on October 3, 2010.

References

- Katz, William Loren. Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage. New York: Atheneum, 1986. ISBN 978-0-689-31196-3.

Further reading

- Bonnett, A. "Shades of Difference: African Native Americans", History Today, 58, 12, December 2008, pp. 40–42

- Sylviane A. Diouf (1998), Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. ISBN 0-8147-1905-8

- Allan D. Austin (1997), African Muslims in Antebellum America. ISBN 0-415-91270-9

- Tiya Miles (2006), Ties that Bind: the Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom. ISBN 0-520-24132-0

- J. Leitch Wright (1999), The Only Land They Knew: American Indians in the Old South. ISBN 0-8032-9805-6

- Patrick Minges (2004), Black Indians Slave Narratives. ISBN 0-89587-298-6

- Jack D. Forbes (1993), Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples. ISBN 0-252-06321-X

- James F. Brooks (2002), Confounding the Color Line: The (American) Indian–Black Experience in North America. ISBN 0-8032-6194-2

- Claudio Saunt (2005), Black, White, and Indian: Race and the Unmaking of an American Family. ISBN 0-19-531310-0

- Valena Broussard Dismukes (2007), The Red-Black Connection: Contemporary Urban African-Native Americans and their Stories of Dual Identity. ISBN 978-0-9797153-0-3

External links

- Ancestors Know Who We Are (2022), NMAI virtual art exhibition of Black-Indigenous women artists

- "Aframerindian Slave Narratives," by Patrick Minges