Confederate States of America

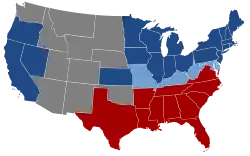

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or simply the Confederacy, was an unrecognized breakaway[1] republic in North America that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865.[8] The Confederacy comprised U.S. states that declared secession and warred against the United States (the Union) during the American Civil War.[8][9] Eleven U.S. states, nicknamed Dixie, declared secession and formed the main part of the CSA. They were South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Kentucky and Missouri also had declarations of secession and full representation in the Confederate Congress during their Union army occupation.

Confederate States of America | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1861–1865 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Flag

(1861–1863)  Seal

(1863–1865) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: Deo vindice ("Under God, our Vindicator") | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthems: "God Save the South" (de facto) "Dixie" (popular, unofficial) March: "The Bonnie Blue Flag" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | New Orleans (until May 1, 1862) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | English (de facto) minor languages : French (Louisiana), Indigenous languages (Indian territory) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Confederate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Confederated presidential non-partisan republic[4][5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

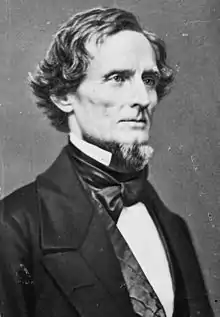

• 1861–1865 | Jefferson Davis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

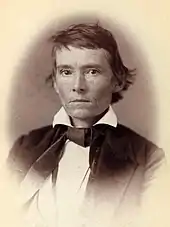

• 1861–1865 | Alexander H. Stephens | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Congress | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | American Civil War / International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Provisional constitution | February 8, 1861 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| April 12, 1861 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Permanent constitution | February 22, 1862 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia | April 9, 1865 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Military Collapse | April 26, 1865 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Debellation and Dissolution | May 5, 1865 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 18601 | 9,103,332 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Slaves2 | 3,521,110 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Confederacy was formed on February 8, 1861, by seven slave states: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas.[10] All seven of the states were located in the Deep South region of the United States, whose economy was heavily dependent upon agriculture—particularly cotton—and a plantation system that relied upon enslaved Americans of African descendent for labor.[11][12] Convinced that white supremacy and slavery were threatened by the November 1860 election of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln to the U.S. presidency, on a platform which opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories, the Confederacy declared its secession from the United States, with the loyal states becoming known as the Union during the ensuing American Civil War.[9][10][7] In the Cornerstone Speech, Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens described its ideology as centrally based "upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition."[13]

Before Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861, a provisional Confederate government was established on February 8, 1861. It was considered illegal by the United States federal government, and Northerners thought of the Confederates as traitors. After war began in April, four slave states of the Upper South—Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina—also joined the Confederacy. The Confederacy later accepted the slave states of Missouri and Kentucky as members, accepting rump state assembly declarations of secession as authorization for full delegations of representatives and senators in the Confederate Congress; they were never substantially controlled by Confederate forces, despite the efforts of Confederate shadow governments, which were eventually expelled. The Union rejected the claims of secession as illegitimate.

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter, a Union fort in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. No foreign government ever recognized the Confederacy as an independent country, although Great Britain and France granted it belligerent status, which allowed Confederate agents to contract with private concerns for weapons and other supplies.[1][14][15] By 1865, the Confederacy's civilian government dissolved into chaos: the Confederate States Congress adjourned sine die, effectively ceasing to exist as a legislative body on March 18. After four years of heavy fighting, nearly all Confederate land and naval forces either surrendered or otherwise ceased hostilities by May 1865.[16][17] The war lacked a clean end, with Confederate forces surrendering or disbanding sporadically throughout most of 1865. The most significant capitulation was Confederate general Robert E. Lee's surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on April 9, after which any doubt about the war's outcome or the Confederacy's survival was extinguished, although another large army under Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston did not formally surrender to William T. Sherman until April 26. Contemporaneously, President Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth on April 15. Confederate President Jefferson Davis's administration declared the Confederacy dissolved on May 5, and acknowledged in later writings that the Confederacy "disappeared" in 1865.[18][19][20] On May 9, 1865, U.S. president Andrew Johnson officially called an end to the armed resistance in the South.

After the war, Confederate states were readmitted to the Congress during the Reconstruction era, after each ratified the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution outlawing slavery. Lost Cause ideology, an idealized view of the Confederacy valiantly fighting for a just cause, emerged in the decades after the war among former Confederate generals and politicians, as well as organizations such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Intense periods of Lost Cause activity developed around the time of World War I, and during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s in reaction to growing support for racial equality. Advocates sought to ensure future generations of Southern whites would continue to support white supremacist policies such as the Jim Crow laws through activities such as building Confederate monuments and influencing textbooks to portray the Confederacy in a favorable light.[21] The modern display of Confederate flags primarily started during the 1948 presidential election, when the battle flag was used by the Dixiecrats, who opposed the Civil Rights Movement; more recently, segregationists have continued the practice, using it for demonstrations.[22][23]

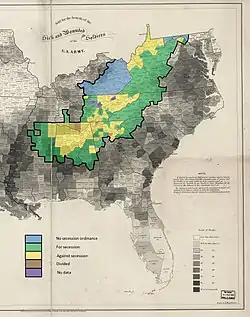

Span of control

On February 22, 1862, the Confederate States Constitution of seven state signatories – Mississippi, South Carolina, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas – replaced the Provisional Constitution of February 8, 1861, with one stating in its preamble a desire for a "permanent federal government". Four additional slave-holding states – Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina – declared their secession and joined the Confederacy following a call by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln for troops from each state to recapture Sumter and other seized federal properties in the South.[24]

Missouri and Kentucky were represented by partisan factions adopting the forms of state governments without control of substantial territory or population in either case. The antebellum state governments in both maintained their representation in the Union. Also fighting for the Confederacy were two of the "Five Civilized Tribes" – the Choctaw and the Chickasaw – in Indian Territory, and a new, but uncontrolled, Confederate Territory of Arizona. Efforts by certain factions in Maryland to secede were halted by federal imposition of martial law; Delaware, though of divided loyalty, did not attempt it. A Unionist government was formed in opposition to the secessionist state government in Richmond and administered the western parts of Virginia that had been occupied by Federal troops. The Restored Government of Virginia later recognized the new state of West Virginia, which was admitted to the Union during the war on June 20, 1863, and relocated to Alexandria for the rest of the war.[24]

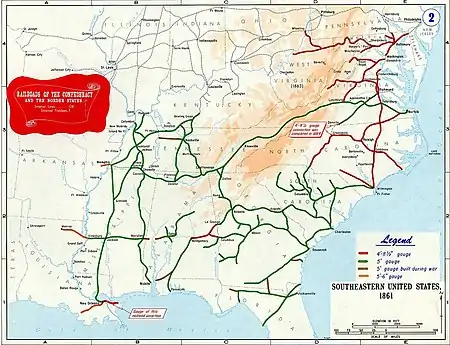

Confederate control over its claimed territory and population in congressional districts steadily shrank from three-quarters to a third during the American Civil War due to the Union's successful overland campaigns, its control of inland waterways into the South, and its blockade of the southern coast.[25] With the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the Union made abolition of slavery a war goal (in addition to reunion). As Union forces moved southward, large numbers of plantation slaves were freed. Many joined the Union lines, enrolling in service as soldiers, teamsters and laborers. The most notable advance was Sherman's "March to the Sea" in late 1864. Much of the Confederacy's infrastructure was destroyed, including telegraphs, railroads, and bridges. Plantations in the path of Sherman's forces were severely damaged. Internal movement within the Confederacy became increasingly difficult, weakening its economy and limiting army mobility.[26]

These losses created an insurmountable disadvantage in men, materiel, and finance. Public support for Confederate President Jefferson Davis's administration eroded over time due to repeated military reverses, economic hardships, and allegations of autocratic government. After four years of campaigning, Richmond was captured by Union forces in April 1865. A few days later General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, effectively signaling the collapse of the Confederacy. President Davis was captured on May 10, 1865, and jailed for treason, but no trial was ever held.[27]

History

The Confederacy was established by the Montgomery Convention in February 1861 by seven states (South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, adding Texas in March before Lincoln's inauguration), expanded in May–July 1861 (with Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, North Carolina), and disintegrated in April–May 1865. It was formed by delegations from seven slave states of the Lower South that had proclaimed their secession from the Union. After the fighting began in April, four additional slave states seceded and were admitted. Later, two slave states (Missouri and Kentucky) and two territories were given seats in the Confederate Congress.[28]

Southern nationalism was rising and pride supported the new founding.[29][30] Confederate nationalism prepared men to fight for "The Southern Cause". For the duration of its existence, the Confederacy underwent trial by war.[31] The Southern Cause transcended the ideology of states' rights, tariff policy, and internal improvements. This "Cause" supported, or derived from, cultural and financial dependence on the South's slavery-based economy. The convergence of race and slavery, politics, and economics raised almost all South-related policy questions to the status of moral questions over way of life, merging love of things Southern and hatred of things Northern. Not only did political parties split, but national churches and interstate families as well divided along sectional lines as the war approached.[32] According to historian John M. Coski,

The statesmen who led the secession movement were unashamed to explicitly cite the defense of slavery as their prime motive ... Acknowledging the centrality of slavery to the Confederacy is essential for understanding the Confederate.[33]

Southern Democrats had chosen John Breckinridge as their candidate during the U.S. presidential election of 1860, but in no Southern state (other than South Carolina, where the legislature chose the electors) was support for him unanimous, as all of the other states recorded at least some popular votes for one or more of the other three candidates (Abraham Lincoln, Stephen A. Douglas and John Bell). Support for these candidates, collectively, ranged from significant to an outright majority, with extremes running from 25% in Texas to 81% in Missouri.[34] There were minority views everywhere, especially in the upland and plateau areas of the South, being particularly concentrated in western Virginia and eastern Tennessee.[35]

Following South Carolina's unanimous 1860 secession vote, no other Southern states considered the question until 1861, and when they did none had a unanimous vote. All had residents who cast significant numbers of Unionist votes in either the legislature, conventions, popular referendums, or in all three. Voting to remain in the Union did not necessarily mean that individuals were sympathizers with the North. Once fighting began, many of these who voted to remain in the Union, particularly in the Deep South, accepted the majority decision, and supported the Confederacy.[36]

Many writers have evaluated the Civil War as an American tragedy—a "Brothers' War", pitting "brother against brother, father against son, kin against kin of every degree".[37][38]

A revolution in disunion

According to historian Avery O. Craven in 1950, the Confederate States of America nation, as a state power, was created by secessionists in Southern slave states, who believed that the federal government was making them second-class citizens.[39] They judged the agents of change to be abolitionists and anti-slavery elements in the Republican Party, whom they believed used repeated insult and injury to subject them to intolerable "humiliation and degradation".[39] The "Black Republicans" (as the Southerners called them) and their allies soon dominated the U.S. House, Senate, and Presidency. On the U.S. Supreme Court, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (a presumed supporter of slavery) was 83 years old and ailing.

During the campaign for president in 1860, some secessionists threatened disunion should Lincoln (who opposed the expansion of slavery into the territories) be elected, including William L. Yancey. Yancey toured the North calling for secession as Stephen A. Douglas toured the South calling for union if Lincoln was elected.[40] To the secessionists the Republican intent was clear: to contain slavery within its present bounds and, eventually, to eliminate it entirely. A Lincoln victory presented them with a momentous choice (as they saw it), even before his inauguration – "the Union without slavery, or slavery without the Union".[41]

Causes of secession

The new [Confederate] Constitution has put at rest forever all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institutions—African slavery as it exists among us—the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson, in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the "rock upon which the old Union would split." He was right. What was conjecture with him, is now a realized fact. But whether he fully comprehended the great truth upon which that rock stood and stands, may be doubted.

The prevailing ideas entertained by him and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old Constitution were, that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with; but the general opinion of the men of that day was, that, somehow or other, in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away... Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the idea of a Government built upon it—when the "storm came and the wind blew, it fell."

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

Alexander H. Stephens, speech to The Savannah Theatre. (March 21, 1861)

The immediate catalyst for secession was the victory of the Republican Party and the election of Abraham Lincoln as president in the 1860 elections. American Civil War historian James M. McPherson suggested that, for Southerners, the most ominous feature of the Republican victories in the congressional and presidential elections of 1860 was the magnitude of those victories: Republicans captured over 60 percent of the Northern vote and three-fourths of its Congressional delegations. The Southern press said that such Republicans represented the anti-slavery portion of the North, "a party founded on the single sentiment ... of hatred of African slavery", and now the controlling power in national affairs. The "Black Republican party" could overwhelm conservative Yankees. The New Orleans Delta said of the Republicans, "It is in fact, essentially, a revolutionary party" to overthrow slavery.[42]

By 1860, sectional disagreements between North and South concerned primarily the maintenance or expansion of slavery in the United States. Historian Drew Gilpin Faust observed that "leaders of the secession movement across the South cited slavery as the most compelling reason for southern independence".[43] Although most white Southerners did not own slaves, the majority supported the institution of slavery and benefited indirectly from the slave society. For struggling yeomen and subsistence farmers, the slave society provided a large class of people ranked lower in the social scale than themselves.[44] Secondary differences related to issues of free speech, runaway slaves, expansion into Cuba, and states' rights.

Historian Emory Thomas assessed the Confederacy's self-image by studying correspondence sent by the Confederate government in 1861–62 to foreign governments. He found that Confederate diplomacy projected multiple contradictory self-images:

The Southern nation was by turns a guileless people attacked by a voracious neighbor, an 'established' nation in some temporary difficulty, a collection of bucolic aristocrats making a romantic stand against the banalities of industrial democracy, a cabal of commercial farmers seeking to make a pawn of King Cotton, an apotheosis of nineteenth-century nationalism and revolutionary liberalism, or the ultimate statement of social and economic reaction.[45]

In what later became known as the Cornerstone Speech, Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens declared that the "cornerstone" of the new government "rest[ed] upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery – subordination to the superior race – is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth".[46] After the war Stephens tried to qualify his remarks, claiming they were extemporaneous, metaphorical, and intended to refer to public sentiment rather than "the principles of the new Government on this subject".[47][48]

Four of the seceding states, the Deep South states of South Carolina,[49] Mississippi,[50] Georgia,[51] and Texas,[52] issued formal declarations of the causes of their decision; each identified the threat to slaveholders' rights as the cause of, or a major cause of, secession. Georgia also claimed a general Federal policy of favoring Northern over Southern economic interests. Texas mentioned slavery 21 times, but also listed the failure of the federal government to live up to its obligations, in the original annexation agreement, to protect settlers along the exposed western frontier. Texas resolutions further stated that governments of the states and the nation were established "exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity". They also stated that although equal civil and political rights applied to all white men, they did not apply to those of the "African race", further opining that the end of racial enslavement would "bring inevitable calamities upon both [races] and desolation upon the fifteen slave-holding states".[52]

Alabama did not provide a separate declaration of causes. Instead, the Alabama ordinance stated "the election of Abraham Lincoln ... by a sectional party, avowedly hostile to the domestic institutions and to the peace and security of the people of the State of Alabama, preceded by many and dangerous infractions of the Constitution of the United States by many of the States and people of the northern section, is a political wrong of so insulting and menacing a character as to justify the people of the State of Alabama in the adoption of prompt and decided measures for their future peace and security". The ordinance invited "the slaveholding States of the South, who may approve such purpose, in order to frame a provisional as well as a permanent Government upon the principles of the Constitution of the United States" to participate in a February 4, 1861 convention in Montgomery, Alabama.[53]

The secession ordinances of the remaining two states, Florida and Louisiana, simply declared their severing ties with the federal Union, without stating any causes.[54][55] Afterward, the Florida secession convention formed a committee to draft a declaration of causes, but the committee was discharged before completion of the task.[56] Only an undated, untitled draft remains.[57]

Four of the Upper South states (Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina) rejected secession until after the clash at Ft. Sumter.[36][58][59][60][61] Virginia's ordinance stated a kinship with the slave-holding states of the Lower South, but did not name the institution itself as a primary reason for its course.[62]

Arkansas's secession ordinance encompassed a strong objection to the use of military force to preserve the Union as its motivating reason.[63] Before the outbreak of war, the Arkansas Convention had on March 20 given as their first resolution: "The people of the Northern States have organized a political party, purely sectional in its character, the central and controlling idea of which is hostility to the institution of African slavery, as it exists in the Southern States; and that party has elected a President ... pledged to administer the Government upon principles inconsistent with the rights and subversive of the interests of the Southern States."[64]

North Carolina and Tennessee limited their ordinances to simply withdrawing, although Tennessee went so far as to make clear they wished to make no comment at all on the "abstract doctrine of secession".[65][66]

In a message to the Confederate Congress on April 29, 1861 Jefferson Davis cited both the tariff and slavery for the South's secession.[67]

Secessionists and conventions

The pro-slavery "Fire-Eaters" group of Southern Democrats, calling for immediate secession, were opposed by two factions. "Cooperationists" in the Deep South would delay secession until several states left the union, perhaps in a Southern Convention. Under the influence of men such as Texas Governor Sam Houston, delay would have the effect of sustaining the Union.[68] "Unionists", especially in the Border South, often former Whigs, appealed to sentimental attachment to the United States. Southern Unionists' favorite presidential candidate was John Bell of Tennessee, sometimes running under an "Opposition Party" banner.[68]

William L. Yancey, Alabama Fire-Eater, "The Orator of Secession"

William L. Yancey, Alabama Fire-Eater, "The Orator of Secession" William Henry Gist, Governor of South Carolina, called the Secessionist Convention

William Henry Gist, Governor of South Carolina, called the Secessionist Convention

Many secessionists were active politically. Governor William Henry Gist of South Carolina corresponded secretly with other Deep South governors, and most southern governors exchanged clandestine commissioners.[69] Charleston's secessionist "1860 Association" published over 200,000 pamphlets to persuade the youth of the South. The most influential were: "The Doom of Slavery" and "The South Alone Should Govern the South", both by John Townsend of South Carolina; and James D. B. De Bow's "The Interest of Slavery of the Southern Non-slaveholder".[70]

Developments in South Carolina started a chain of events. The foreman of a jury refused the legitimacy of federal courts, so Federal Judge Andrew Magrath ruled that U.S. judicial authority in South Carolina was vacated. A mass meeting in Charleston celebrating the Charleston and Savannah railroad and state cooperation led to the South Carolina legislature to call for a Secession Convention. U.S. Senator James Chesnut, Jr. resigned, as did Senator James Henry Hammond.[71]

Elections for Secessionist conventions were heated to "an almost raving pitch, no one dared dissent", according to historian William W. Freehling. Even once–respected voices, including the Chief Justice of South Carolina, John Belton O'Neall, lost election to the Secession Convention on a Cooperationist ticket. Across the South mobs expelled Yankees and (in Texas) executed German-Americans suspected of loyalty to the United States.[72] Generally, seceding conventions which followed did not call for a referendum to ratify, although Texas, Arkansas, and Tennessee did, as well as Virginia's second convention. Kentucky declared neutrality, while Missouri had its own civil war until the Unionists took power and drove the Confederate legislators out of the state.[73]

Attempts to thwart secession

In the antebellum months, the Corwin Amendment was an unsuccessful attempt by the Congress to bring the seceding states back to the Union and to convince the border slave states to remain.[74] It was a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution by Ohio Congressman Thomas Corwin that would shield "domestic institutions" of the states (which in 1861 included slavery) from the constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by Congress.[75][76]

It was passed by the 36th Congress on March 2, 1861. The House approved it by a vote of 133 to 65 and the United States Senate adopted it, with no changes, on a vote of 24 to 12. It was then submitted to the state legislatures for ratification.[77] In his inaugural address Lincoln endorsed the proposed amendment.

The text was as follows:

No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.

Had it been ratified by the required number of states prior to 1865, it would have made institutionalized slavery immune to the constitutional amendment procedures and to interference by Congress.[78][79]

Inauguration and response

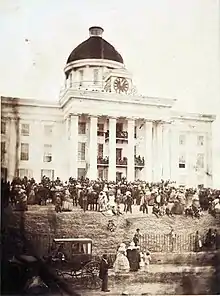

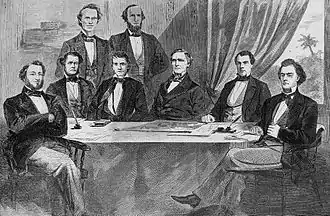

The first secession state conventions from the Deep South sent representatives to meet at the Montgomery Convention in Montgomery, Alabama, on February 4, 1861. There the fundamental documents of government were promulgated, a provisional government was established, and a representative Congress met for the Confederate States of America.[80]

The new 'provisional' Confederate President Jefferson Davis issued a call for 100,000 men from the various states' militias to defend the newly formed Confederacy.[80] All Federal property was seized, along with gold bullion and coining dies at the U.S. mints in Charlotte, North Carolina; Dahlonega, Georgia; and New Orleans.[80] The Confederate capital was moved from Montgomery to Richmond, Virginia, in May 1861. On February 22, 1862, Davis was inaugurated as president with a term of six years.[81]

The newly inaugurated Confederate administration pursued a policy of national territorial integrity, continuing earlier state efforts in 1860 and early 1861 to remove U.S. government presence from within their boundaries. These efforts included taking possession of U.S. courts, custom houses, post offices, and most notably, arsenals and forts. But after the Confederate attack and capture of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Lincoln called up 75,000 of the states' militia to muster under his command. The stated purpose was to re-occupy U.S. properties throughout the South, as the U.S. Congress had not authorized their abandonment. The resistance at Fort Sumter signaled his change of policy from that of the Buchanan Administration. Lincoln's response ignited a firestorm of emotion. The people of both North and South demanded war, with soldiers rushing to their colors in the hundreds of thousands. Four more states (Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas) refused Lincoln's call for troops and declared secession, while Kentucky maintained an uneasy "neutrality".[80]

Secession

Secessionists argued that the United States Constitution was a contract among sovereign states that could be abandoned at any time without consultation and that each state had a right to secede. After intense debates and statewide votes, seven Deep South cotton states passed secession ordinances by February 1861 (before Abraham Lincoln took office as president), while secession efforts failed in the other eight slave states. Delegates from those seven formed the CSA in February 1861, selecting Jefferson Davis as the provisional president. Unionist talk of reunion failed and Davis began raising a 100,000 man army.[82]

States

Initially, some secessionists may have hoped for a peaceful departure.[83] Moderates in the Confederate Constitutional Convention included a provision against importation of slaves from Africa to appeal to the Upper South. Non-slave states might join, but the radicals secured a two-thirds requirement in both houses of Congress to accept them.[84]

Seven states declared their secession from the United States before Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861. After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter April 12, 1861, and Lincoln's subsequent call for troops on April 15, four more states declared their secession:[85]

Kentucky declared neutrality but after Confederate troops moved in, the state government asked for Union troops to drive them out. The splinter Confederate state government relocated to accompany western Confederate armies and never controlled the state population. By the end of the war, 90,000 Kentuckians had fought on the side of the Union, compared to 35,000 for the Confederate States.[86]

In Missouri, a constitutional convention was approved and delegates elected by voters. The convention rejected secession 89–1 on March 19, 1861.[87] The governor maneuvered to take control of the St. Louis Arsenal and restrict Federal movements. This led to confrontation, and in June Federal forces drove him and the General Assembly from Jefferson City. The executive committee of the constitutional convention called the members together in July. The convention declared the state offices vacant, and appointed a Unionist interim state government.[88] The exiled governor called a rump session of the former General Assembly together in Neosho and, on October 31, 1861, passed an ordinance of secession.[89][90] It is still a matter of debate as to whether a quorum existed for this vote. The Confederate state government was unable to control very much Missouri territory. It had its capital first at Neosho, then at Cassville, before being driven out of the state. For the remainder of the war, it operated as a government in exile at Marshall, Texas.[91]

Neither Kentucky nor Missouri was declared in rebellion in Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. The Confederacy recognized the pro-Confederate claimants in both Kentucky (December 10, 1861) and Missouri (November 28, 1861) and laid claim to those states, granting them Congressional representation and adding two stars to the Confederate flag. Voting for the representatives was mostly done by Confederate soldiers from Kentucky and Missouri.[92]

The order of secession resolutions and dates are:

- 1. South Carolina (December 20, 1860)[93]

- 2. Mississippi (January 9, 1861)[94]

- 3. Florida (January 10)[95]

- 4. Alabama (January 11)[96]

- 5. Georgia (January 19)[97]

- 6. Louisiana (January 26)[98]

- 7. Texas (February 1; referendum February 23)[99]

- Inauguration of President Lincoln, March 4

- Bombardment of Fort Sumter (April 12) and President Lincoln's call-up (April 15)[100]

- 8. Virginia (April 17; referendum May 23, 1861)[101]

- 9. Arkansas (May 6)[102]

- 10. Tennessee (May 7; referendum June 8)[103]

- 11. North Carolina (May 20)[104]

In Virginia, the populous counties along the Ohio and Pennsylvania borders rejected the Confederacy. Unionists held a Convention in Wheeling in June 1861, establishing a "restored government" with a rump legislature, but sentiment in the region remained deeply divided. In the 50 counties that would make up the state of West Virginia, voters from 24 counties had voted for disunion in Virginia's May 23 referendum on the ordinance of secession.[105] In the 1860 Presidential election "Constitutional Democrat" Breckenridge had outpolled "Constitutional Unionist" Bell in the 50 counties by 1,900 votes, 44% to 42%.[106] Regardless of scholarly disputes over election procedures and results county by county, altogether they simultaneously supplied over 20,000 soldiers to each side of the conflict.[107][108] Representatives for most of the counties were seated in both state legislatures at Wheeling and at Richmond for the duration of the war.[109]

Attempts to secede from the Confederacy by some counties in East Tennessee were checked by martial law.[110] Although slave-holding Delaware and Maryland did not secede, citizens from those states exhibited divided loyalties. Regiments of Marylanders fought in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.[111] But overall, 24,000 men from Maryland joined the Confederate armed forces, compared to 63,000 who joined Union forces.[86]

Delaware never produced a full regiment for the Confederacy, but neither did it emancipate slaves as did Missouri and West Virginia. District of Columbia citizens made no attempts to secede and through the war years, referendums sponsored by President Lincoln approved systems of compensated emancipation and slave confiscation from "disloyal citizens".[112]

Territories

Citizens at Mesilla and Tucson in the southern part of New Mexico Territory formed a secession convention, which voted to join the Confederacy on March 16, 1861, and appointed Dr. Lewis S. Owings as the new territorial governor. They won the Battle of Mesilla and established a territorial government with Mesilla serving as its capital.[113] The Confederacy proclaimed the Confederate Arizona Territory on February 14, 1862, north to the 34th parallel. Marcus H. MacWillie served in both Confederate Congresses as Arizona's delegate. In 1862 the Confederate New Mexico Campaign to take the northern half of the U.S. territory failed and the Confederate territorial government in exile relocated to San Antonio, Texas.[114]

Confederate supporters in the trans-Mississippi west also claimed portions of the Indian Territory after the United States evacuated the federal forts and installations. Over half of the American Indian troops participating in the Civil War from the Indian Territory supported the Confederacy; troops and one general were enlisted from each tribe. On July 12, 1861, the Confederate government signed a treaty with both the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indian nations. After several battles Union armies took control of the territory.[115]

The Indian Territory never formally joined the Confederacy, but it did receive representation in the Confederate Congress. Many Indians from the Territory were integrated into regular Confederate Army units. After 1863 the tribal governments sent representatives to the Confederate Congress: Elias Cornelius Boudinot representing the Cherokee and Samuel Benton Callahan representing the Seminole and Creek people. The Cherokee Nation aligned with the Confederacy. They practiced and supported slavery, opposed abolition, and feared their lands would be seized by the Union. After the war, the Indian territory was disestablished, their black slaves were freed, and the tribes lost some of their lands.[116]

Capitals

Montgomery, Alabama, served as the capital of the Confederate States of America from February 4 until May 29, 1861, in the Alabama State Capitol. Six states created the Confederate States of America there on February 8, 1861. The Texas delegation was seated at the time, so it is counted in the "original seven" states of the Confederacy; it had no roll call vote until after its referendum made secession "operative".[117] Two sessions of the Provisional Congress were held in Montgomery, adjourning May 21.[118] The Permanent Constitution was adopted there on March 12, 1861.[119]

The permanent capital provided for in the Confederate Constitution called for a state cession of a ten-miles square (100 square mile) district to the central government. Atlanta, which had not yet supplanted Milledgeville, Georgia, as its state capital, put in a bid noting its central location and rail connections, as did Opelika, Alabama, noting its strategically interior situation, rail connections and nearby deposits of coal and iron.[120]

Richmond, Virginia, was chosen for the interim capital at the Virginia State Capitol. The move was used by Vice President Stephens and others to encourage other border states to follow Virginia into the Confederacy. In the political moment it was a show of "defiance and strength". The war for Southern independence was surely to be fought in Virginia, but it also had the largest Southern military-aged white population, with infrastructure, resources, and supplies required to sustain a war. The Davis Administration's policy was that, "It must be held at all hazards."[121]

The naming of Richmond as the new capital took place on May 30, 1861, and the last two sessions of the Provisional Congress were held in the new capital. The Permanent Confederate Congress and President were elected in the states and army camps on November 6, 1861. The First Congress met in four sessions in Richmond from February 18, 1862, to February 17, 1864. The Second Congress met there in two sessions, from May 2, 1864, to March 18, 1865.[122]

As war dragged on, Richmond became crowded with training and transfers, logistics and hospitals. Prices rose dramatically despite government efforts at price regulation. A movement in Congress led by Henry S. Foote of Tennessee argued for moving the capital from Richmond. At the approach of Federal armies in mid-1862, the government's archives were readied for removal. As the Wilderness Campaign progressed, Congress authorized Davis to remove the executive department and call Congress to session elsewhere in 1864 and again in 1865. Shortly before the end of the war, the Confederate government evacuated Richmond, planning to relocate farther south. Little came of these plans before Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia on April 9, 1865.[123] Davis and most of his cabinet fled to Danville, Virginia, which served as their headquarters for eight days.

Southern Unionism

Unionism—opposition to the Confederacy—was widespread in the mountain regions of Appalachia and the Ozarks.[124] Unionists, led by Parson Brownlow and Senator Andrew Johnson, took control of eastern Tennessee in 1863.[125] Unionists also attempted control over western Virginia but never effectively held more than half of the counties that formed the new state of West Virginia.[126][127][128] Union forces captured parts of coastal North Carolina, and at first were welcomed by local unionists. That changed as the occupiers became perceived as oppressive, callous, radical and favorable to the Freedmen. Occupiers pillaged, freed slaves, and evicted those who refused to swear loyalty oaths to the Union.[129]

Support for the Confederacy was perhaps weakest in Texas; Claude Elliott estimates that only a third of the population actively supported the Confederacy. Many Unionists supported the Confederacy after the war began, but many others clung to their Unionism throughout the war, especially in the northern counties, the German districts, and the Mexican areas.[130] According to Ernest Wallace: "This account of a dissatisfied Unionist minority, although historically essential, must be kept in its proper perspective, for throughout the war the overwhelming majority of the people zealously supported the Confederacy ..."[131] Randolph B. Campbell states, "In spite of terrible losses and hardships, most Texans continued throughout the war to support the Confederacy as they had supported secession".[132] Dale Baum in his analysis of Texas politics in the era counters: "This idea of a Confederate Texas united politically against northern adversaries was shaped more by nostalgic fantasies than by wartime realities." He characterizes Texas Civil War history as "a morose story of intragovernmental rivalries coupled with wide-ranging disaffection that prevented effective implementation of state wartime policies".[133]

In Texas, local officials harassed and murdered Unionists and Germans. In Cooke County, 150 suspected Unionists were arrested; 25 were lynched without trial and 40 more were hanged after a summary trial. Draft resistance was widespread especially among Texans of German or Mexican descent; many of the latter went to Mexico. Confederate officials hunted down and killed potential draftees who had gone into hiding.[130]

Civil liberties were of small concern in both the North and South. Lincoln and Davis both took a hard line against dissent. Neely explores how the Confederacy became a virtual police state with guards and patrols all about, and a domestic passport system whereby everyone needed official permission each time they wanted to travel. Over 4,000 suspected Unionists were imprisoned without trial.[134]

United States, a foreign power

During the four years of its existence under trial by war, the Confederate States of America asserted its independence and appointed dozens of diplomatic agents abroad. None were ever officially recognized by a foreign government. The United States government regarded the Southern states as being in rebellion or insurrection and so refused any formal recognition of their status.

Even before Fort Sumter, U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward issued formal instructions to the American minister to Britain, Charles Francis Adams:

[Make] no expressions of harshness or disrespect, or even impatience concerning the seceding States, their agents, or their people, [those States] must always continue to be, equal and honored members of this Federal Union, [their citizens] still are and always must be our kindred and countrymen.[135]

Seward instructed Adams that if the British government seemed inclined to recognize the Confederacy, or even waver in that regard, it was to receive a sharp warning, with a strong hint of war:

[if Britain is] tolerating the application of the so-called seceding States, or wavering about it, [they cannot] remain friends with the United States ... if they determine to recognize [the Confederacy], [Britain] may at the same time prepare to enter into alliance with the enemies of this republic.[135]

The United States government never declared war on those "kindred and countrymen" in the Confederacy, but conducted its military efforts beginning with a presidential proclamation issued April 15, 1861.[136] It called for troops to recapture forts and suppress what Lincoln later called an "insurrection and rebellion".[137]

Mid-war parleys between the two sides occurred without formal political recognition, though the laws of war predominantly governed military relationships on both sides of uniformed conflict.[138]

On the part of the Confederacy, immediately following Fort Sumter the Confederate Congress proclaimed that "war exists between the Confederate States and the Government of the United States, and the States and Territories thereof". A state of war was not to formally exist between the Confederacy and those states and territories in the United States allowing slavery, although Confederate Rangers were compensated for destruction they could effect there throughout the war.[139]

Concerning the international status and nationhood of the Confederate States of America, in 1869 the United States Supreme Court in Texas v. White, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 700 (1869) ruled Texas' declaration of secession was legally null and void.[140] Jefferson Davis, former President of the Confederacy, and Alexander H. Stephens, its former vice-president, both wrote postwar arguments in favor of secession's legality and the international legitimacy of the Government of the Confederate States of America, most notably Davis' The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.

International diplomacy

Once war with the United States began, the Confederacy pinned its hopes for survival on military intervention by Great Britain and/or France. The Confederate government sent James M. Mason to London and John Slidell to Paris. On their way to Europe in 1861, the U.S. Navy intercepted their ship, the Trent, and forcibly took them to Boston, an international episode known as the Trent Affair. The diplomats were eventually released and continued their voyage to Europe.[141] However, their mission was unsuccessful; historians give them low marks for their poor diplomacy.[142] Neither secured diplomatic recognition for the Confederacy, much less military assistance.

The Confederates who had believed that "cotton is king", that is, that Britain had to support the Confederacy to obtain cotton, proved mistaken. The British had stocks to last over a year and had been developing alternative sources of cotton, most notably India and Egypt. Britain had so much cotton that it was exporting some to France.[143] England was not about to go to war with the U.S. to acquire more cotton at the risk of losing the large quantities of food imported from the North.[144][145]

Aside from the purely economic questions, there was also the clamorous ethical debate. Great Britain took pride in being a leader in suppressing slavery, ending it in its empire in 1833, and the end of the Atlantic slave trade was enforced by British vessels. Confederate diplomats found little support for American slavery, cotton trade or not. A series of slave narratives about American slavery was being published in London.[146] It was in London that the first World Anti-Slavery Convention had been held in 1840; it was followed by regular smaller conferences. A string of eloquent and sometimes well-educated Negro abolitionist speakers crisscrossed not just England but Scotland and Ireland as well. In addition to exposing the reality of America's shameful and sinful chattel slavery—some were fugitive slaves—they rebutted the Confederate position that negroes were "unintellectual, timid, and dependent",[147] and "not equal to the white man...the superior race," as it was put by Confederate Vice-president Alexander H. Stephens in his famous Cornerstone Speech. Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, Sarah Parker Remond, her brother Charles Lenox Remond, James W. C. Pennington, Martin Delany, Samuel Ringgold Ward, and William G. Allen all spent years in Britain, where fugitive slaves were safe and, as Allen said, there was an "absence of prejudice against color. Here the colored man feels himself among friends, and not among enemies".[148] One speaker alone, William Wells Brown, gave more than 1,000 lectures on the shame of American chattel slavery.[149]: 32

.jpg.webp)

Throughout the early years of the war, British foreign secretary Lord John Russell, Emperor Napoleon III of France, and, to a lesser extent, British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, showed interest in recognition of the Confederacy or at least mediation of the war. British Chancellor of the Exchequer William Gladstone, convinced of the necessity of intervention on the Confederate side based on the successful diplomatic intervention in Second Italian War of Independence against Austria, attempted unsuccessfully to convince Lord Palmerston to intervene.[150] By September 1862 the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln's preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and abolitionist opposition in Britain put an end to these possibilities.[151] The cost to Britain of a war with the U.S. would have been high: the immediate loss of American grain-shipments, the end of British exports to the U.S., and the seizure of billions of pounds invested in American securities. War would have meant higher taxes in Britain, another invasion of Canada, and full-scale worldwide attacks on the British merchant fleet. Outright recognition would have meant certain war with the United States; in mid-1862 fears of race war (as had transpired in the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804) led to the British considering intervention for humanitarian reasons. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation did not lead to interracial violence, let alone a bloodbath, but it did give the friends of the Union strong talking points in the arguments that raged across Britain.[152]

John Slidell, the Confederate States emissary to France, did succeed in negotiating a loan of $15,000,000 from Erlanger and other French capitalists. The money went to buy ironclad warships, as well as military supplies that came in with blockade runners.[153] The British government did allow the construction of blockade runners in Britain; they were owned and operated by British financiers and ship owners; a few were owned and operated by the Confederacy. The British investors' goal was to get highly profitable cotton.[154]

Several European nations maintained diplomats in place who had been appointed to the U.S., but no country appointed any diplomat to the Confederacy. Those nations recognized the Union and Confederate sides as belligerents. In 1863 the Confederacy expelled European diplomatic missions for advising their resident subjects to refuse to serve in the Confederate army.[155] Both Confederate and Union agents were allowed to work openly in British territories. Some state governments in northern Mexico negotiated local agreements to cover trade on the Texas border.[156] The Confederacy appointed Ambrose Dudley Mann as special agent to the Holy See on September 24, 1863. But the Holy See never released a formal statement supporting or recognizing the Confederacy. In November 1863, Mann met Pope Pius IX in person and received a letter supposedly addressed "to the Illustrious and Honorable Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America"; Mann had mistranslated the address. In his report to Richmond, Mann claimed a great diplomatic achievement for himself, asserting the letter was "a positive recognition of our Government". The letter was indeed used in propaganda, but Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin told Mann it was "a mere inferential recognition, unconnected with political action or the regular establishment of diplomatic relations" and thus did not assign it the weight of formal recognition.[157][158]

Nevertheless, the Confederacy was seen internationally as a serious attempt at nationhood, and European governments sent military observers, both official and unofficial, to assess whether there had been a de facto establishment of independence. These observers included Arthur Lyon Fremantle of the British Coldstream Guards, who entered the Confederacy via Mexico, Fitzgerald Ross of the Austrian Hussars, and Justus Scheibert of the Prussian Army.[159] European travelers visited and wrote accounts for publication. Importantly in 1862, the Frenchman Charles Girard's Seven months in the rebel states during the North American War testified "this government ... is no longer a trial government ... but really a normal government, the expression of popular will".[160] Fremantle went on to write in his book Three Months in the Southern States that he had

not attempted to conceal any of the peculiarities or defects of the Southern people. Many persons will doubtless highly disapprove of some of their customs and habits in the wilder portion of the country; but I think no generous man, whatever may be his political opinions, can do otherwise than admire the courage, energy, and patriotism of the whole population, and the skill of its leaders, in this struggle against great odds. And I am also of opinion that many will agree with me in thinking that a people in which all ranks and both sexes display a unanimity and a heroism which can never have been surpassed in the history of the world, is destined, sooner or later, to become a great and independent nation.[161]

French Emperor Napoleon III assured Confederate diplomat John Slidell that he would make "direct proposition" to Britain for joint recognition. The Emperor made the same assurance to British Members of Parliament John A. Roebuck and John A. Lindsay.[162] Roebuck in turn publicly prepared a bill to submit to Parliament June 30 supporting joint Anglo-French recognition of the Confederacy. "Southerners had a right to be optimistic, or at least hopeful, that their revolution would prevail, or at least endure."[163] Following the double disasters at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in July 1863, the Confederates "suffered a severe loss of confidence in themselves", and withdrew into an interior defensive position. There would be no help from the Europeans.[164]

By December 1864, Davis considered sacrificing slavery in order to enlist recognition and aid from Paris and London; he secretly sent Duncan F. Kenner to Europe with a message that the war was fought solely for "the vindication of our rights to self-government and independence" and that "no sacrifice is too great, save that of honor". The message stated that if the French or British governments made their recognition conditional on anything at all, the Confederacy would consent to such terms.[165] Davis's message could not explicitly acknowledge that slavery was on the bargaining table due to still-strong domestic support for slavery among the wealthy and politically influential. European leaders all saw that the Confederacy was on the verge of total defeat.[166]

Cuba and Brazil

The Confederacy's biggest foreign policy successes were with Cuba and Brazil. Militarily this meant little during the war. Brazil represented the "peoples most identical to us in Institutions",[167] in which slavery remained legal until the 1880s. Cuba was a Spanish colony and the Captain–General of Cuba declared in writing that Confederate ships were welcome, and would be protected in Cuban ports.[167] They were also welcome in Brazilian ports;[168] slavery was legal throughout Brazil, and the abolitionist movement was small. After the end of the war, Brazil was the primary destination of those Southerners who wanted to continue living in a slave society, where, as one immigrant remarked, slaves were cheap (see Confederados). Historians speculate that if the Confederacy had achieved independence, it probably would have tried to acquire Cuba as a base of expansion.[169]

Motivations of soldiers

Most soldiers who joined Confederate national or state military units joined voluntarily. Perman (2010) says historians are of two minds on why millions of soldiers seemed so eager to fight, suffer and die over four years:

Some historians emphasize that Civil War soldiers were driven by political ideology, holding firm beliefs about the importance of liberty, Union, or state rights, or about the need to protect or to destroy slavery. Others point to less overtly political reasons to fight, such as the defense of one's home and family, or the honor and brotherhood to be preserved when fighting alongside other men. Most historians agree that, no matter what he thought about when he went into the war, the experience of combat affected him profoundly and sometimes affected his reasons for continuing to fight.[170][171]

Military strategy

Civil War historian E. Merton Coulter wrote that for those who would secure its independence, "The Confederacy was unfortunate in its failure to work out a general strategy for the whole war". Aggressive strategy called for offensive force concentration. Defensive strategy sought dispersal to meet demands of locally minded governors. The controlling philosophy evolved into a combination "dispersal with a defensive concentration around Richmond". The Davis administration considered the war purely defensive, a "simple demand that the people of the United States would cease to war upon us".[172] Historian James M. McPherson is a critic of Lee's offensive strategy: "Lee pursued a faulty military strategy that ensured Confederate defeat".[173]

As the Confederate government lost control of territory in campaign after campaign, it was said that "the vast size of the Confederacy would make its conquest impossible". The enemy would be struck down by the same elements which so often debilitated or destroyed visitors and transplants in the South. Heat exhaustion, sunstroke, endemic diseases such as malaria and typhoid would match the destructive effectiveness of the Moscow winter on the invading armies of Napoleon.[174]

Early in the war both sides believed that one great battle would decide the conflict; the Confederates won a surprise victory at the First Battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas (the name used by Confederate forces). It drove the Confederate people "insane with joy"; the public demanded a forward movement to capture Washington, relocate the Confederate capital there, and admit Maryland to the Confederacy.[176] A council of war by the victorious Confederate generals decided not to advance against larger numbers of fresh Federal troops in defensive positions. Davis did not countermand it. Following the Confederate incursion into Maryland halted at the Battle of Antietam in October 1862, generals proposed concentrating forces from state commands to re-invade the north. Nothing came of it.[177] Again in mid-1863 at his incursion into Pennsylvania, Lee requested that Davis Beauregard simultaneously attack Washington with troops taken from the Carolinas. But the troops there remained in place during the Gettysburg Campaign.

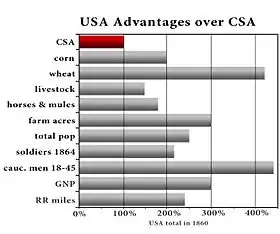

The eleven states of the Confederacy were outnumbered by the North about four-to-one in military manpower. It was overmatched far more in military equipment, industrial facilities, railroads for transport, and wagons supplying the front.

Confederates slowed the Yankee invaders, at heavy cost to the Southern infrastructure. The Confederates burned bridges, laid land mines in the roads, and made harbors inlets and inland waterways unusable with sunken mines (called "torpedoes" at the time). Coulter reports:

Rangers in twenty to fifty-man units were awarded 50% valuation for property destroyed behind Union lines, regardless of location or loyalty. As Federals occupied the South, objections by loyal Confederate concerning Ranger horse-stealing and indiscriminate scorched earth tactics behind Union lines led to Congress abolishing the Ranger service two years later.[178]

The Confederacy relied on external sources for war materials. The first came from trade with the enemy. "Vast amounts of war supplies" came through Kentucky, and thereafter, western armies were "to a very considerable extent" provisioned with illicit trade via Federal agents and northern private traders.[179] But that trade was interrupted in the first year of war by Admiral Porter's river gunboats as they gained dominance along navigable rivers north–south and east–west.[180] Overseas blockade running then came to be of "outstanding importance".[181] On April 17, President Davis called on privateer raiders, the "militia of the sea", to wage war on U.S. seaborne commerce.[182] Despite noteworthy effort, over the course of the war the Confederacy was found unable to match the Union in ships and seamanship, materials and marine construction.[183]

An inescapable obstacle to success in the warfare of mass armies was the Confederacy's lack of manpower, and sufficient numbers of disciplined, equipped troops in the field at the point of contact with the enemy. During the winter of 1862–63, Lee observed that none of his famous victories had resulted in the destruction of the opposing army. He lacked reserve troops to exploit an advantage on the battlefield as Napoleon had done. Lee explained, "More than once have most promising opportunities been lost for want of men to take advantage of them, and victory itself had been made to put on the appearance of defeat, because our diminished and exhausted troops have been unable to renew a successful struggle against fresh numbers of the enemy."[184]

Armed forces

The military armed forces of the Confederacy comprised three branches: Army, Navy and Marine Corps.

The Confederate military leadership included many veterans from the United States Army and United States Navy who had resigned their Federal commissions and were appointed to senior positions. Many had served in the Mexican–American War (including Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis), but some such as Leonidas Polk (who graduated from West Point but did not serve in the Army) had little or no experience.

.svg.png.webp) Navy Jack – light blue cross; also square canton, white fly

Navy Jack – light blue cross; also square canton, white fly Battle Flag – square

Battle Flag – square

The Confederate officer corps consisted of men from both slave-owning and non-slave-owning families. The Confederacy appointed junior and field grade officers by election from the enlisted ranks. Although no Army service academy was established for the Confederacy, some colleges (such as The Citadel and Virginia Military Institute) maintained cadet corps that trained Confederate military leadership. A naval academy was established at Drewry's Bluff, Virginia[185] in 1863, but no midshipmen graduated before the Confederacy's end.

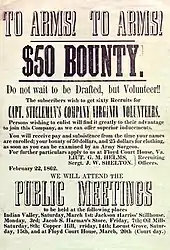

Most soldiers were white males aged between 16 and 28. The median year of birth was 1838, so half the soldiers were 23 or older by 1861.[186] In early 1862, the Confederate Army was allowed to disintegrate for two months following expiration of short-term enlistments. Most of those in uniform would not re-enlist following their one-year commitment, so on April 16, 1862, the Confederate Congress enacted the first mass conscription on the North American continent. (The U.S. Congress followed a year later on March 3, 1863, with the Enrollment Act.) Rather than a universal draft, the initial program was a selective service with physical, religious, professional and industrial exemptions. These were narrowed as the war progressed. Initially substitutes were permitted, but by December 1863 these were disallowed. In September 1862 the age limit was increased from 35 to 45 and by February 1864, all men under 18 and over 45 were conscripted to form a reserve for state defense inside state borders. By March 1864, the Superintendent of Conscription reported that all across the Confederacy, every officer in constituted authority, man and woman, "engaged in opposing the enrolling officer in the execution of his duties".[187] Although challenged in the state courts, the Confederate State Supreme Courts routinely rejected legal challenges to conscription.[188]

Many thousands of slaves served as personal servants to their owner, or were hired as laborers, cooks, and pioneers.[189] Some freed blacks and men of color served in local state militia units of the Confederacy, primarily in Louisiana and South Carolina, but their officers deployed them for "local defense, not combat".[190] Depleted by casualties and desertions, the military suffered chronic manpower shortages. In early 1865, the Confederate Congress, influenced by the public support by General Lee, approved the recruitment of black infantry units. Contrary to Lee's and Davis's recommendations, the Congress refused "to guarantee the freedom of black volunteers". No more than two hundred black combat troops were ever raised.[191]

Raising troops

The immediate onset of war meant that it was fought by the "Provisional" or "Volunteer Army". State governors resisted concentrating a national effort. Several wanted a strong state army for self-defense. Others feared large "Provisional" armies answering only to Davis.[192] When filling the Confederate government's call for 100,000 men, another 200,000 were turned away by accepting only those enlisted "for the duration" or twelve-month volunteers who brought their own arms or horses.[193]

It was important to raise troops; it was just as important to provide capable officers to command them. With few exceptions the Confederacy secured excellent general officers. Efficiency in the lower officers was "greater than could have been reasonably expected". As with the Federals, political appointees could be indifferent. Otherwise, the officer corps was governor-appointed or elected by unit enlisted. Promotion to fill vacancies was made internally regardless of merit, even if better officers were immediately available.[194]

Anticipating the need for more "duration" men, in January 1862 Congress provided for company level recruiters to return home for two months, but their efforts met little success on the heels of Confederate battlefield defeats in February.[195] Congress allowed for Davis to require numbers of recruits from each governor to supply the volunteer shortfall. States responded by passing their own draft laws.[196]

The veteran Confederate army of early 1862 was mostly twelve-month volunteers with terms about to expire. Enlisted reorganization elections disintegrated the army for two months. Officers pleaded with the ranks to re-enlist, but a majority did not. Those remaining elected majors and colonels whose performance led to officer review boards in October. The boards caused a "rapid and widespread" thinning out of 1,700 incompetent officers. Troops thereafter would elect only second lieutenants.[197]

In early 1862, the popular press suggested the Confederacy required a million men under arms. But veteran soldiers were not re-enlisting, and earlier secessionist volunteers did not reappear to serve in war. One Macon, Georgia, newspaper asked how two million brave fighting men of the South were about to be overcome by four million northerners who were said to be cowards.[198]

Conscription

The Confederacy passed the first American law of national conscription on April 16, 1862. The white males of the Confederate States from 18 to 35 were declared members of the Confederate army for three years, and all men then enlisted were extended to a three-year term. They would serve only in units and under officers of their state. Those under 18 and over 35 could substitute for conscripts, in September those from 35 to 45 became conscripts.[199] The cry of "rich man's war and a poor man's fight" led Congress to abolish the substitute system altogether in December 1863. All principals benefiting earlier were made eligible for service. By February 1864, the age bracket was made 17 to 50, those under eighteen and over forty-five to be limited to in-state duty.[200]

Confederate conscription was not universal; it was a selective service. The First Conscription Act of April 1862 exempted occupations related to transportation, communication, industry, ministers, teaching and physical fitness. The Second Conscription Act of October 1862 expanded exemptions in industry, agriculture and conscientious objection. Exemption fraud proliferated in medical examinations, army furloughs, churches, schools, apothecaries and newspapers.[201]

Rich men's sons were appointed to the socially outcast "overseer" occupation, but the measure was received in the country with "universal odium". The legislative vehicle was the controversial Twenty Negro Law that specifically exempted one white overseer or owner for every plantation with at least 20 slaves. Backpedaling six months later, Congress provided overseers under 45 could be exempted only if they held the occupation before the first Conscription Act.[202] The number of officials under state exemptions appointed by state Governor patronage expanded significantly.[203] By law, substitutes could not be subject to conscription, but instead of adding to Confederate manpower, unit officers in the field reported that over-50 and under-17-year-old substitutes made up to 90% of the desertions.[204]

Gen. Gabriel J. Rains, Conscription Bureau chief, April 1862 – May 1863

Gen. Gabriel J. Rains, Conscription Bureau chief, April 1862 – May 1863 Gen. Gideon J. Pillow, military recruiter under Bragg, then J.E. Johnston[205]

Gen. Gideon J. Pillow, military recruiter under Bragg, then J.E. Johnston[205]

The Conscription Act of February 1864 "radically changed the whole system" of selection. It abolished industrial exemptions, placing detail authority in President Davis. As the shame of conscription was greater than a felony conviction, the system brought in "about as many volunteers as it did conscripts." Many men in otherwise "bombproof" positions were enlisted in one way or another, nearly 160,000 additional volunteers and conscripts in uniform. Still there was shirking.[206] To administer the draft, a Bureau of Conscription was set up to use state officers, as state Governors would allow. It had a checkered career of "contention, opposition and futility". Armies appointed alternative military "recruiters" to bring in the out-of-uniform 17–50-year-old conscripts and deserters. Nearly 3,000 officers were tasked with the job. By late 1864, Lee was calling for more troops. "Our ranks are constantly diminishing by battle and disease, and few recruits are received; the consequences are inevitable." By March 1865 conscription was to be administered by generals of the state reserves calling out men over 45 and under 18 years old. All exemptions were abolished. These regiments were assigned to recruit conscripts ages 17–50, recover deserters, and repel enemy cavalry raids. The service retained men who had lost but one arm or a leg in home guards. Ultimately, conscription was a failure, and its main value was in goading men to volunteer.[207]

The survival of the Confederacy depended on a strong base of civilians and soldiers devoted to victory. The soldiers performed well, though increasing numbers deserted in the last year of fighting, and the Confederacy never succeeded in replacing casualties as the Union could. The civilians, although enthusiastic in 1861–62, seem to have lost faith in the future of the Confederacy by 1864, and instead looked to protect their homes and communities. As Rable explains, "This contraction of civic vision was more than a crabbed libertarianism; it represented an increasingly widespread disillusionment with the Confederate experiment."[208]

Victories: 1861

The American Civil War broke out in April 1861 with a Confederate victory at the Battle of Fort Sumter in Charleston.

.jpg.webp)

In January, President James Buchanan had attempted to resupply the garrison with the steamship, Star of the West, but Confederate artillery drove it away. In March, President Lincoln notified South Carolina Governor Pickens that without Confederate resistance to the resupply there would be no military reinforcement without further notice, but Lincoln prepared to force resupply if it were not allowed. Confederate President Davis, in cabinet, decided to seize Fort Sumter before the relief fleet arrived, and on April 12, 1861, General Beauregard forced its surrender.[210]

Following Sumter, Lincoln directed states to provide 75,000 troops for three months to recapture the Charleston Harbor forts and all other federal property.[211] This emboldened secessionists in Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina to secede rather than provide troops to march into neighboring Southern states. In May, Federal troops crossed into Confederate territory along the entire border from the Chesapeake Bay to New Mexico. The first battles were Confederate victories at Big Bethel (Bethel Church, Virginia), First Bull Run (First Manassas) in Virginia July and in August, Wilson's Creek (Oak Hills) in Missouri. At all three, Confederate forces could not follow up their victory due to inadequate supply and shortages of fresh troops to exploit their successes. Following each battle, Federals maintained a military presence and occupied Washington, DC; Fort Monroe, Virginia; and Springfield, Missouri. Both North and South began training up armies for major fighting the next year.[212] Union General George B. McClellan's forces gained possession of much of northwestern Virginia in mid-1861, concentrating on towns and roads; the interior was too large to control and became the center of guerrilla activity.[213][214] General Robert E. Lee was defeated at Cheat Mountain in September and no serious Confederate advance in western Virginia occurred until the next year.

Meanwhile, the Union Navy seized control of much of the Confederate coastline from Virginia to South Carolina. It took over plantations and the abandoned slaves. Federals there began a war-long policy of burning grain supplies up rivers into the interior wherever they could not occupy.[215] The Union Navy began a blockade of the major southern ports and prepared an invasion of Louisiana to capture New Orleans in early 1862.

Incursions: 1862

The victories of 1861 were followed by a series of defeats east and west in early 1862. To restore the Union by military force, the Federal strategy was to (1) secure the Mississippi River, (2) seize or close Confederate ports, and (3) march on Richmond. To secure independence, the Confederate intent was to (1) repel the invader on all fronts, costing him blood and treasure, and (2) carry the war into the North by two offensives in time to affect the mid-term elections.

Much of northwestern Virginia was under Federal control.[217] In February and March, most of Missouri and Kentucky were Union "occupied, consolidated, and used as staging areas for advances further South". Following the repulse of Confederate counter-attack at the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, permanent Federal occupation expanded west, south and east.[218] Confederate forces repositioned south along the Mississippi River to Memphis, Tennessee, where at the naval Battle of Memphis, its River Defense Fleet was sunk. Confederates withdrew from northern Mississippi and northern Alabama. New Orleans was captured April 29 by a combined Army-Navy force under U.S. Admiral David Farragut, and the Confederacy lost control of the mouth of the Mississippi River. It had to concede extensive agricultural resources that had supported the Union's sea-supplied logistics base.[219]

Although Confederates had suffered major reverses everywhere, as of the end of April the Confederacy still controlled territory holding 72% of its population.[220] Federal forces disrupted Missouri and Arkansas; they had broken through in western Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee and Louisiana. Along the Confederacy's shores, Union forces had closed ports and made garrisoned lodgments on every coastal Confederate state except Alabama and Texas.[221] Although scholars sometimes assess the Union blockade as ineffectual under international law until the last few months of the war, from the first months it disrupted Confederate privateers, making it "almost impossible to bring their prizes into Confederate ports".[222] British firms developed small fleets of blockade running companies, such as John Fraser and Company and S. Isaac, Campbell & Company while the Ordnance Department secured its own blockade runners for dedicated munitions cargoes.[223]