Canada

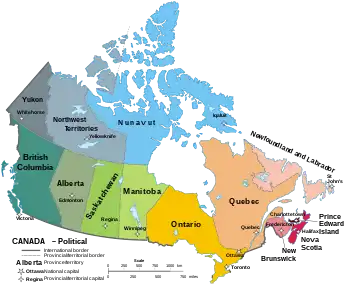

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over 9.98 million square kilometres (3.85 million square miles), making it the world's second-largest country by total area. Its southern and western border with the United States, stretching 8,891 kilometres (5,525 mi), is the world's longest binational land border. Canada's capital is Ottawa, and its three largest metropolitan areas are Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver.

Canada | |

|---|---|

| Motto: A mari usque ad mare (Latin) "From Sea to Sea" | |

| Anthem: "O Canada" | |

| |

| Capital | Ottawa 45°24′N 75°40′W |

| Largest city | Toronto |

| Official languages |

|

| Ethnic groups | See below |

| Religion | See below |

| Demonym(s) | Canadian |

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy[2] |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Mary Simon | |

| Justin Trudeau | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Commons | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

• Confederation | July 1, 1867 |

| December 11, 1931 | |

• Patriation | April 17, 1982 |

| Area | |

• Total area | 9,984,670 km2 (3,855,100 sq mi) (2nd) |

• Water (%) | 11.76 (as of 2015)[3] |

• Total land area | 9,093,507 km2 (3,511,023 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Q3 2022 estimate | 38,929,902[4] (37th) |

• 2021 census | 36,991,981[5] |

• Density | 4.2/km2 (10.9/sq mi) (236th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 15th |

| Currency | Canadian dollar ($) (CAD) |

| Time zone | UTC−3.5 to −8 |

| UTC−2.5 to −7 | |

| Date format | yyyy-mm-dd (AD)[9] |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +1 |

| Internet TLD | .ca |

Indigenous peoples have continuously inhabited what is now Canada for thousands of years. Beginning in the 16th century, British and French expeditions explored and later settled along the Atlantic coast. As a consequence of various armed conflicts, France ceded nearly all of its colonies in North America in 1763. In 1867, with the union of three British North American colonies through Confederation, Canada was formed as a federal dominion of four provinces. This began an accretion of provinces and territories and a process of increasing autonomy from the United Kingdom. This widening autonomy was highlighted by the Statute of Westminster 1931 and culminated in the Canada Act 1982, which severed the vestiges of legal dependence on the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Canada is a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy in the Westminster tradition. The country's head of government is the prime minister—who holds office by virtue of their ability to command the confidence of the elected House of Commons—and is appointed by the governor general, representing the monarch, who serves as head of state. The country is a Commonwealth realm and is officially bilingual (English and French) at the federal level. It ranks among the highest in international measurements of government transparency, civil liberties, quality of life, economic freedom, education, gender equality and environmental sustainability. It is one of the world's most ethnically diverse and multicultural nations, the product of large-scale immigration. Canada's long and complex relationship with the United States has had a significant impact on its economy and culture.

A highly developed country, Canada has the 24th highest nominal per capita income globally and the sixteenth-highest ranking on the Human Development Index. Its advanced economy is the eighth-largest in the world, relying chiefly upon its abundant natural resources and well-developed international trade networks. Canada is part of several major international and intergovernmental institutions or groupings including the United Nations, NATO, the G7, the Group of Ten, the G20, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Commonwealth of Nations, the Arctic Council, the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, and the Organization of American States.

Etymology

While a variety of theories have been postulated for the etymological origins of Canada, the name is now accepted as coming from the St. Lawrence Iroquoian word kanata, meaning "village" or "settlement".[10] In 1535, Indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Quebec City region used the word to direct French explorer Jacques Cartier to the village of Stadacona.[11] Cartier later used the word Canada to refer not only to that particular village but to the entire area subject to Donnacona (the chief at Stadacona);[11] by 1545, European books and maps had begun referring to this small region along the Saint Lawrence River as Canada.[11]

From the 16th to the early 18th century, "Canada" referred to the part of New France that lay along the Saint Lawrence River.[12] In 1791, the area became two British colonies called Upper Canada and Lower Canada. These two colonies were collectively named the Canadas until their union as the British Province of Canada in 1841.[13]

Upon Confederation in 1867, Canada was adopted as the legal name for the new country at the London Conference, and the word Dominion was conferred as the country's title.[14] By the 1950s, the term Dominion of Canada was no longer used by the United Kingdom, which considered Canada a "Realm of the Commonwealth".[15] The government of Louis St. Laurent ended the practice of using Dominion in the statutes of Canada in 1951.[16][17][18]

The Canada Act 1982, which brought the constitution of Canada fully under Canadian control, referred only to Canada. Later that year, the name of the national holiday was changed from Dominion Day to Canada Day.[19] The term Dominion was used to distinguish the federal government from the provinces, though after the Second World War the term federal had replaced dominion.[20]

History

Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples in present-day Canada include the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis,[21] the last being of mixed descent who originated in the mid-17th century when First Nations people married European settlers and subsequently developed their own identity.[21]

The first inhabitants of North America are generally hypothesized to have migrated from Siberia by way of the Bering land bridge and arrived at least 14,000 years ago.[22][23] The Paleo-Indian archeological sites at Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are two of the oldest sites of human habitation in Canada.[24] The characteristics of Indigenous societies included permanent settlements, agriculture, complex societal hierarchies, and trading networks.[25][26] Some of these cultures had collapsed by the time European explorers arrived in the late 15th and early 16th centuries and have only been discovered through archeological investigations.[27]

The Indigenous population at the time of the first European settlements is estimated to have been between 200,000[28] and two million,[29] with a figure of 500,000 accepted by Canada's Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.[30] As a consequence of European colonization, the Indigenous population declined by forty to eighty percent, and several First Nations, such as the Beothuk, disappeared.[31] The decline is attributed to several causes, including the transfer of European diseases, such as influenza, measles, and smallpox to which they had no natural immunity,[28][32] conflicts over the fur trade, conflicts with the colonial authorities and settlers, and the loss of Indigenous lands to settlers and the subsequent collapse of several nations' self-sufficiency.[33][34]

Although not without conflict, European Canadians' early interactions with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful.[35] First Nations and Métis peoples played a critical part in the development of European colonies in Canada, particularly for their role in assisting European coureur des bois and voyageurs in their explorations of the continent during the North American fur trade.[36] The Crown and Indigenous peoples began interactions during the European colonization period, though the Inuit, in general, had more limited interaction with European settlers.[37] From the late 18th century, European Canadians forced Indigenous peoples to assimilate into a western culture.[38] These attempts reached a climax in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with forced integration and relocations.[39] A period of redress is underway, which started with the appointment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada by the Government of Canada in 2008.[40]

European colonization

It is believed that the first European to explore the east coast of Canada was Norse explorer Leif Erikson.[41][42] In approximately 1000 AD, the Norse built a small short-lived encampment that was occupied sporadically for perhaps 20 years at L'Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland.[43] No further European exploration occurred until 1497, when Italian seafarer John Cabot explored and claimed Canada's Atlantic coast in the name of King Henry VII of England.[44] In 1534, French explorer Jacques Cartier explored the Gulf of Saint Lawrence where, on July 24, he planted a 10-metre (33 ft) cross bearing the words "Long Live the King of France" and took possession of the territory New France in the name of King Francis I.[45] The early 16th century saw European mariners with navigational techniques pioneered by the Basque and Portuguese establish seasonal whaling and fishing outposts along the Atlantic coast.[46] In general, early settlements during the Age of Discovery appear to have been short-lived due to a combination of the harsh climate, problems with navigating trade routes and competing outputs in Scandinavia.[47][48]

In 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, by the royal prerogative of Queen Elizabeth I, founded St. John's, Newfoundland, as the first North American English seasonal camp.[49] In 1600, the French established their first seasonal trading post at Tadoussac along the Saint Lawrence.[43] French explorer Samuel de Champlain arrived in 1603 and established the first permanent year-round European settlements at Port Royal (in 1605) and Quebec City (in 1608).[50] Among the colonists of New France, Canadiens extensively settled the Saint Lawrence River valley and Acadians settled the present-day Maritimes, while fur traders and Catholic missionaries explored the Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, and the Mississippi watershed to Louisiana.[51] The Beaver Wars broke out in the mid-17th century over control of the North American fur trade.[52]

The English established additional settlements in Newfoundland in 1610 along with settlements in the Thirteen Colonies to the south.[53][54] A series of four wars erupted in colonial North America between 1689 and 1763; the later wars of the period constituted the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War.[55] Mainland Nova Scotia came under British rule with the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, and Canada and most of New France came under British rule in 1763 after the Seven Years' War.[56]

British North America

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 established First Nation treaty rights, created the Province of Quebec out of New France, and annexed Cape Breton Island to Nova Scotia.[19] St. John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became a separate colony in 1769.[57] To avert conflict in Quebec, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act 1774, expanding Quebec's territory to the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley.[58] More importantly, the Quebec Act afforded Quebec special autonomy and rights of self-administration at a time when the Thirteen Colonies were increasingly agitating against British rule.[59] It re-established the French language, Catholic faith, and French civil law there, staving off the growth of an independence movement in contrast to the Thirteen Colonies.[60] The Proclamation and the Quebec Act in turn angered many residents of the Thirteen Colonies, further fuelling anti-British sentiment in the years prior to the American Revolution.[19]

After the successful American War of Independence, the 1783 Treaty of Paris recognized the independence of the newly formed United States and set the terms of peace, ceding British North American territories south of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi River to the new country.[61] The American war of independence also caused a large out-migration of Loyalists, the settlers who had fought against American independence. Many moved to Canada, particularly Atlantic Canada, where their arrival changed the demographic distribution of the existing territories. New Brunswick was in turn split from Nova Scotia as part of a reorganization of Loyalist settlements in the Maritimes, which led to the incorporation of Saint John, New Brunswick, as Canada's first city.[62] To accommodate the influx of English-speaking Loyalists in Central Canada, the Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the province of Canada into French-speaking Lower Canada (later Quebec) and English-speaking Upper Canada (later Ontario), granting each its own elected legislative assembly.[63]

The Canadas were the main front in the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. Peace came in 1815; no boundaries were changed.[64] Immigration resumed at a higher level, with over 960,000 arrivals from Britain between 1815 and 1850.[65] New arrivals included refugees escaping the Great Irish Famine as well as Gaelic-speaking Scots displaced by the Highland Clearances.[66] Infectious diseases killed between 25 and 33 percent of Europeans who immigrated to Canada before 1891.[28]

The desire for responsible government resulted in the abortive Rebellions of 1837.[67] The Durham Report subsequently recommended responsible government and the assimilation of French Canadians into English culture.[19] The Act of Union 1840 merged the Canadas into a united Province of Canada and responsible government was established for all provinces of British North America east of Lake Superior by 1855.[68] The signing of the Oregon Treaty by Britain and the United States in 1846 ended the Oregon boundary dispute, extending the border westward along the 49th parallel. This paved the way for British colonies on Vancouver Island (1849) and in British Columbia (1858).[69] The Anglo-Russian Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1825) established the border along the Pacific coast, but, even after the US Alaska Purchase of 1867, disputes continued about the exact demarcation of the Alaska–Yukon and Alaska–BC border.[70]

Confederation and expansion

Following several constitutional conferences, the British North America Act 1867 officially proclaimed Canadian Confederation on July 1, 1867, initially with four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.[71][72] Canada assumed control of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory to form the Northwest Territories, where the Métis' grievances ignited the Red River Rebellion and the creation of the province of Manitoba in July 1870.[73] British Columbia and Vancouver Island (which had been united in 1866) joined the confederation in 1871 on the promise of a transcontinental railway extending to Victoria in the province within 10 years,[74] while Prince Edward Island joined in 1873.[75] In 1898, during the Klondike Gold Rush in the Northwest Territories, Parliament created the Yukon Territory. Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces in 1905.[75] Between 1871 and 1896, almost one quarter of the Canadian population emigrated south to the U.S.[76]

To open the West and encourage European immigration, Parliament approved sponsoring the construction of three transcontinental railways (including the Canadian Pacific Railway), opening the prairies to settlement with the Dominion Lands Act, and establishing the North-West Mounted Police to assert its authority over this territory.[77][78] This period of westward expansion and nation building resulted in the displacement of many Indigenous peoples of the Canadian Prairies to "Indian reserves",[79] clearing the way for ethnic European block settlements.[80] This caused the collapse of the Plains Bison in western Canada and the introduction of European cattle farms and wheat fields dominating the land.[81] The Indigenous peoples saw widespread famine and disease due to the loss of the bison and their traditional hunting lands.[82] The federal government did provide emergency relief, on condition of the Indigenous peoples moving to the reserves.[83] During this time, Canada introduced the Indian Act extending its control over the First Nations to education, government and legal rights.[84]

Early 20th century

Because Britain still maintained control of Canada's foreign affairs under the British North America Act, 1867, its declaration of war in 1914 automatically brought Canada into World War I.[85] Volunteers sent to the Western Front later became part of the Canadian Corps, which played a substantial role in the Battle of Vimy Ridge and other major engagements of the war.[86] Out of approximately 625,000 Canadians who served in World War I, some 60,000 were killed and another 172,000 were wounded.[87] The Conscription Crisis of 1917 erupted when the Unionist Cabinet's proposal to augment the military's dwindling number of active members with conscription was met with vehement objections from French-speaking Quebecers.[88] The Military Service Act brought in compulsory military service, though it, coupled with disputes over French language schools outside Quebec, deeply alienated Francophone Canadians and temporarily split the Liberal Party.[88] In 1919, Canada joined the League of Nations independently of Britain,[86] and the Statute of Westminster, 1931 affirmed Canada's independence.[89]

The Great Depression in Canada during the early 1930s saw an economic downturn, leading to hardship across the country.[90] In response to the downturn, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in Saskatchewan introduced many elements of a welfare state (as pioneered by Tommy Douglas) in the 1940s and 1950s.[91] On the advice of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, war with Germany was declared effective September 10, 1939, by King George VI, seven days after the United Kingdom. The delay underscored Canada's independence.[86]

The first Canadian Army units arrived in Britain in December 1939. In all, over a million Canadians served in the armed forces during World War II and approximately 42,000 were killed and another 55,000 were wounded.[92] Canadian troops played important roles in many key battles of the war, including the failed 1942 Dieppe Raid, the Allied invasion of Italy, the Normandy landings, the Battle of Normandy, and the Battle of the Scheldt in 1944.[86] Canada provided asylum for the Dutch monarchy while that country was occupied and is credited by the Netherlands for major contributions to its liberation from Nazi Germany.[93]

The Canadian economy boomed during the war as its industries manufactured military materiel for Canada, Britain, China, and the Soviet Union.[86] Despite another Conscription Crisis in Quebec in 1944, Canada finished the war with a large army and strong economy.[94]

Contemporary era

The financial crisis of the Great Depression had led the Dominion of Newfoundland to relinquish responsible government in 1934 and become a Crown colony ruled by a British governor.[95] After two referendums, Newfoundlanders voted to join Canada in 1949 as a province.[96]

Canada's post-war economic growth, combined with the policies of successive Liberal governments, led to the emergence of a new Canadian identity, marked by the adoption of the Maple Leaf Flag in 1965,[97] the implementation of official bilingualism (English and French) in 1969,[98] and the institution of official multiculturalism in 1971.[99] Socially democratic programs were also instituted, such as Medicare, the Canada Pension Plan, and Canada Student Loans, though provincial governments, particularly Quebec and Alberta, opposed many of these as incursions into their jurisdictions.[100]

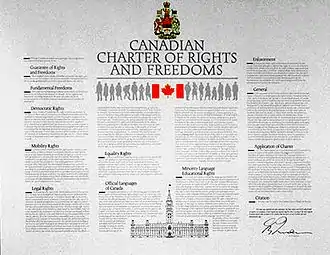

Finally, another series of constitutional conferences resulted in the UK's Canada Act 1982, the patriation of Canada's constitution from the United Kingdom, concurrent with the creation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[101][102][103] Canada had established complete sovereignty as an independent country, although the monarch is retained as sovereign.[104][105] In 1999, Nunavut became Canada's third territory after a series of negotiations with the federal government.[106]

At the same time, Quebec underwent profound social and economic changes through the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, giving birth to a secular nationalist movement.[107] The radical Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) ignited the October Crisis with a series of bombings and kidnappings in 1970[108] and the sovereignist Parti Québécois was elected in 1976, organizing an unsuccessful referendum on sovereignty-association in 1980. Attempts to accommodate Quebec nationalism constitutionally through the Meech Lake Accord failed in 1990.[109] This led to the formation of the Bloc Québécois in Quebec and the invigoration of the Reform Party of Canada in the West.[110][111] A second referendum followed in 1995, in which sovereignty was rejected by a slimmer margin of 50.6 to 49.4 percent.[112] In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession by a province would be unconstitutional and the Clarity Act was passed by parliament, outlining the terms of a negotiated departure from Confederation.[109]

In addition to the issues of Quebec sovereignty, a number of crises shook Canadian society in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These included the explosion of Air India Flight 182 in 1985, the largest mass murder in Canadian history;[113] the École Polytechnique massacre in 1989, a university shooting targeting female students;[114] and the Oka Crisis of 1990,[115] the first of a number of violent confrontations between the government and Indigenous groups.[116] Canada also joined the Gulf War in 1990 as part of a United States–led coalition force and was active in several peacekeeping missions in the 1990s, including the UNPROFOR mission in the former Yugoslavia.[117] Canada sent troops to Afghanistan in 2001 but declined to join the United States–led invasion of Iraq in 2003.[118]

In 2011, Canadian forces participated in the NATO-led intervention into the Libyan Civil War,[119] and also became involved in battling the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq in the mid-2010s.[120] The COVID-19 pandemic in Canada began on January 27, 2020, with wide social and economic disruption.[121] In 2021, the remains of hundreds of Indigenous people were discovered near the former sites of Canadian Indian residential schools.[122] Administered by the Canadian Catholic Church and funded by the Canadian government from 1828 to 1997, these boarding schools attempted to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture.[123]

Geography

By total area (including its waters), Canada is the second-largest country in the world, after Russia.[124] By land area alone, Canada ranks fourth, due to having the world's largest area of fresh water lakes.[125] Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the east, along the Arctic Ocean to the north, and to the Pacific Ocean in the west, the country encompasses 9,984,670 km2 (3,855,100 sq mi) of territory.[126] Canada also has vast maritime terrain, with the world's longest coastline of 243,042 kilometres (151,019 mi).[127][128] In addition to sharing the world's largest land border with the United States—spanning 8,891 km (5,525 mi)—Canada shares a land border with Greenland (and hence the Kingdom of Denmark) to the northeast on Hans Island[129] and a maritime boundary with France's overseas collectivity of Saint Pierre and Miquelon to the southeast.[130] Canada is also home to the world's northernmost settlement, Canadian Forces Station Alert, on the northern tip of Ellesmere Island—latitude 82.5°N—which lies 817 kilometres (508 mi) from the North Pole.[131]

Canada can be divided into seven physiographic regions: the Canadian Shield, the interior plains, the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Lowlands, the Appalachian region, the Western Cordillera, Hudson Bay Lowlands and the Arctic Archipelago.[132] Boreal forests prevail throughout the country, ice is prominent in northern Arctic regions and through the Rocky Mountains, and the relatively flat Canadian Prairies in the southwest facilitate productive agriculture.[126] The Great Lakes feed the St. Lawrence River (in the southeast) where the lowlands host much of Canada's economic output.[126] Canada has over 2,000,000 lakes—563 of which are larger than 100 km2 (39 sq mi)—containing much of the world's fresh water.[133][134] There are also fresh-water glaciers in the Canadian Rockies, the Coast Mountains and the Arctic Cordillera.[135] Canada is geologically active, having many earthquakes and potentially active volcanoes, notably Mount Meager massif, Mount Garibaldi, Mount Cayley, and the Mount Edziza volcanic complex.[136]

Climate

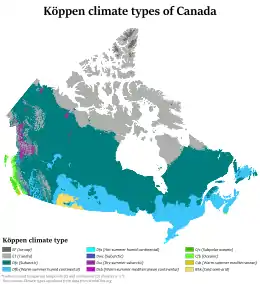

Average winter and summer high temperatures across Canada vary from region to region. Winters can be harsh in many parts of the country, particularly in the interior and Prairie provinces, which experience a continental climate, where daily average temperatures are near −15 °C (5 °F), but can drop below −40 °C (−40 °F) with severe wind chills.[137] In non-coastal regions, snow can cover the ground for almost six months of the year, while in parts of the north snow can persist year-round. Coastal British Columbia has a temperate climate, with a mild and rainy winter. On the east and west coasts, average high temperatures are generally in the low 20s °C (70s °F), while between the coasts, the average summer high temperature ranges from 25 to 30 °C (77 to 86 °F), with temperatures in some interior locations occasionally exceeding 40 °C (104 °F).[138]

Much of Northern Canada is covered by ice and permafrost. The future of the permafrost is uncertain because the Arctic has been warming at three times the global average as a result of climate change in Canada.[139] Canada's annual average temperature over land has warmed by 1.7 °C (3.1 °F), with changes ranging from 1.1 to 2.3 °C (2.0 to 4.1 °F) in various regions, since 1948.[140] The rate of warming has been higher across the North and in the Prairies.[140] In the southern regions of Canada, air pollution from both Canada and the United States—caused by metal smelting, burning coal to power utilities, and vehicle emissions—has resulted in acid rain, which has severely impacted waterways, forest growth and agricultural productivity in Canada.[141]

Biodiversity

Canada is divided into fifteen terrestrial and five marine ecozones.[142] These ecozones encompass over 80,000 classified species of Canadian wildlife, with an equal number yet to be formally recognized or discovered.[143] Although Canada has a low percentage of endemic species compared to other countries,[144] due to human activities, invasive species and environmental issues in the country, there are currently more than 800 species at risk of being lost.[145] About 65 percent of Canada's resident species are considered "Secure".[146] Over half of Canada's landscape is intact and relatively free of human development.[147] The boreal forest of Canada is considered to be the largest intact forest on Earth, with approximately 3,000,000 km2 (1,200,000 sq mi) undisturbed by roads, cities or industry.[148] Since the end of the last glacial period, Canada has consisted of eight distinct forest regions,[149] with 42 percent of its land area covered by forests (approximately 8 percent of the world's forested land).[150]

Approximately 12.1 percent of the nation's landmass and freshwater are conservation areas, including 11.4 percent designated as protected areas.[151] Approximately 13.8 percent of its territorial waters are conserved, including 8.9 percent designated as protected areas.[151] Canada's first National Park, Banff National Park established in 1885, spans 6,641 square kilometres (2,564 sq mi)[152] of mountainous terrain, with many glaciers and ice fields, dense coniferous forest, and alpine landscapes.[153] Canada's oldest provincial park, Algonquin Provincial Park, established in 1893, covers an area of 7,653.45 square kilometres (2,955.01 sq mi). It is dominated by old-growth forest with over 2,400 lakes and 1,200 kilometres of streams and rivers.[154] Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area is the world's largest freshwater protected area, spanning roughly 10,000 square kilometres (3,900 sq mi) of lakebed, its overlaying freshwater, and associated shoreline on 60 square kilometres (23 sq mi) of islands and mainland.[155] Canada's largest national wildlife region is the Scott Islands Marine National Wildlife Area, which spans 11,570.65 square kilometres (4,467.45 sq mi)[156] and protects critical breeding and nesting habitat for over 40 percent of British Columbia's seabirds.[157] Canada's 18 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves cover a total area of 235,000 square kilometres (91,000 sq mi).[158]

Government and politics

Canada is described as a "full democracy",[159] with a tradition of liberalism,[160] and an egalitarian,[161] moderate political ideology.[162] An emphasis on social justice has been a distinguishing element of Canada's political culture.[163][164] Peace, order, and good government, alongside an Implied Bill of Rights, are founding principles of the Canadian government.[165][166]

At the federal level, Canada has been dominated by two relatively centrist parties practising "brokerage politics",[lower-alpha 1] the centre-left leaning Liberal Party of Canada and the centre-right leaning Conservative Party of Canada (or its predecessors).[173] The historically predominant Liberal Party position themselves at the centre of the Canadian political spectrum,[174] with the Conservative Party positioned on the right and the New Democratic Party occupying the left.[175][176] Far-right and far-left politics have never been a prominent force in Canadian society.[177][178][179] Five parties had representatives elected to the Parliament in the 2021 election—the Liberal Party, who currently form a minority government; the Conservative Party, who are the Official Opposition; the New Democratic Party; the Bloc Québécois; and the Green Party of Canada.[180]

Canada has a parliamentary system within the context of a constitutional monarchy—the monarchy of Canada being the foundation of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.[181][182][183] The reigning monarch is King Charles III, who is also monarch of 14 other Commonwealth countries and each of Canada's 10 provinces. The person who is the Canadian monarch is the same as the British monarch, although the two institutions are separate.[184] The monarch appoints a representative, the governor general, with the advice of the prime minister, to carry out most of their federal royal duties in Canada.[185][186]

While the monarchy is the source of authority in Canada, in practice its position is mainly symbolic.[183][187][188] The use of the executive powers is directed by the Cabinet, a committee of ministers of the Crown responsible to the elected House of Commons and chosen and headed by the prime minister (at present Justin Trudeau),[189] the head of government. The governor general or monarch may, though, in certain crisis situations exercise their power without ministerial advice.[187] To ensure the stability of government, the governor general will usually appoint as prime minister the individual who is the current leader of the political party that can obtain the confidence of a plurality in the House of Commons.[190] The Prime Minister's Office (PMO) is thus one of the most powerful institutions in government, initiating most legislation for parliamentary approval and selecting for appointment by the Crown, besides the aforementioned, the governor general, lieutenant governors, senators, federal court judges, and heads of Crown corporations and government agencies.[187] The leader of the party with the second-most seats usually becomes the leader of the Official Opposition and is part of an adversarial parliamentary system intended to keep the government in check.[191]

Each of the 338 members of Parliament in the House of Commons is elected by simple plurality in an electoral district or riding. General elections in Canada must be called by the governor general, either on the advice of the prime minister or if the government loses a confidence vote in the House.[192][193] The Constitution Act, 1982 requires that no more than five years pass between elections, although the Canada Elections Act limits this to four years with a fixed election date in October. The 105 members of the Senate, whose seats are apportioned on a regional basis, serve until age 75.[194]

Canadian federalism divides government responsibilities between the federal government and the ten provinces. Provincial legislatures are unicameral and operate in parliamentary fashion similar to the House of Commons.[188] Canada's three territories also have legislatures, but these are not sovereign and have fewer constitutional responsibilities than the provinces.[195] The territorial legislatures also differ structurally from their provincial counterparts.[196]

The Bank of Canada is the central bank of the country. In addition, the minister of finance and minister of innovation, science and industry utilize the Statistics Canada agency for financial planning and economic policy development.[197] The Bank of Canada is the sole authority authorized to issue currency in the form of Canadian bank notes.[198] The bank does not issue Canadian coins; they are issued by the Royal Canadian Mint.[199]

Law

The Constitution of Canada is the supreme law of the country, and consists of written text and unwritten conventions.[200] The Constitution Act, 1867 (known as the British North America Act prior to 1982), affirmed governance based on parliamentary precedent and divided powers between the federal and provincial governments.[201] The Statute of Westminster, 1931 granted full autonomy, and the Constitution Act, 1982 ended all legislative ties to Britain, as well as adding a constitutional amending formula and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[202] The Charter guarantees basic rights and freedoms that usually cannot be over-ridden by any government—though a notwithstanding clause allows Parliament and the provincial legislatures to override certain sections of the Charter for a period of five years.[203]

Canada's judiciary plays an important role in interpreting laws and has the power to strike down Acts of Parliament that violate the constitution. The Supreme Court of Canada is the highest court and final arbiter and has been led since December 18, 2017, by Richard Wagner, the chief justice of Canada.[204] The governor general appoints its nine members on the advice of the prime minister and minister of justice. All judges at the superior and appellate levels are appointed after consultation with non-governmental legal bodies. The federal Cabinet also appoints justices to superior courts in the provincial and territorial jurisdictions.[205]

Common law prevails everywhere except in Quebec, where civil law predominates.[206] Criminal law is solely a federal responsibility and is uniform throughout Canada.[207] Law enforcement, including criminal courts, is officially a provincial responsibility, conducted by provincial and municipal police forces.[208] In most rural and some urban areas, policing responsibilities are contracted to the federal Royal Canadian Mounted Police.[209]

Canadian Aboriginal law provides certain constitutionally recognized rights to land and traditional practices for Indigenous groups in Canada.[210] Various treaties and case laws were established to mediate relations between Europeans and many Indigenous peoples.[211] Most notably, a series of eleven treaties known as the Numbered Treaties were signed between the Indigenous peoples and the reigning monarch of Canada between 1871 and 1921.[212] These treaties are agreements between the Canadian Crown-in-Council with the duty to consult and accommodate.[213] The role of Aboriginal law and the rights they support were reaffirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.[211] These rights may include provision of services, such as health care through the Indian Health Transfer Policy, and exemption from taxation.[214]

Foreign relations and military

Canada is recognized as a middle power for its role in international affairs with a tendency to pursue multilateral solutions.[215] Canada's foreign policy based on international peacekeeping and security is carried out through coalitions and international organizations, and through the work of numerous federal institutions.[216][217] Canada's peacekeeping role during the 20th century has played a major role in its global image.[218][219] The strategy of the Canadian government's foreign aid policy reflects an emphasis to meet the Millennium Development Goals, while also providing assistance in response to foreign humanitarian crises.[220]

Canada was a founding member of the United Nations and has membership in the World Trade Organization, the G20 and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).[215] Canada is also a member of various other international and regional organizations and forums for economic and cultural affairs.[221] Canada acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1976.[222] Canada joined the Organization of American States (OAS) in 1990 and hosted the OAS General Assembly in 2000 and the 3rd Summit of the Americas in 2001.[223] Canada seeks to expand its ties to Pacific Rim economies through membership in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC).[224]

Canada and the United States share the world's longest undefended border, co-operate on military campaigns and exercises, and are each other's largest trading partner.[225][226] Canada nevertheless has an independent foreign policy.[227] For example, it maintains full relations with Cuba and declined to participate in the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[228]

Canada maintains historic ties to the United Kingdom and France and to other former British and French colonies through Canada's membership in the Commonwealth of Nations and the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie.[229] Canada is noted for having a positive relationship with the Netherlands, owing, in part, to its contribution to the Dutch liberation during World War II.[93]

Canada's strong attachment to the British Empire and Commonwealth led to major participation in British military efforts in the Second Boer War (1899–1902), World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945).[230] Since then, Canada has been an advocate for multilateralism, making efforts to resolve global issues in collaboration with other nations.[231][232] During the Cold War, Canada was a major contributor to UN forces in the Korean War and founded the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) in cooperation with the United States to defend against potential aerial attacks from the Soviet Union.[233]

During the Suez Crisis of 1956, future prime minister Lester B. Pearson eased tensions by proposing the inception of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force, for which he was awarded the 1957 Nobel Peace Prize.[234] As this was the first UN peacekeeping mission, Pearson is often credited as the inventor of the concept.[235] Canada has since served in over 50 peacekeeping missions, including every UN peacekeeping effort until 1989,[86] and has since maintained forces in international missions in Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia, and elsewhere; Canada has sometimes faced controversy over its involvement in foreign countries, notably in the 1993 Somalia affair.[236]

In 2001, Canada deployed troops to Afghanistan as part of the U.S. stabilization force and the UN-authorized, NATO-led International Security Assistance Force.[237] In August 2007, Canada's territorial claims in the Arctic were challenged after a Russian underwater expedition to the North Pole; Canada has considered that area to be sovereign territory since 1925.[238]

The unified Canadian Forces (CF) comprise the Royal Canadian Navy, Canadian Army, and Royal Canadian Air Force. The nation employs a professional, volunteer force of approximately 68,000 active personnel and 27,000 reserve personnel, increasing to 71,500 and 30,000 respectively under "Strong, Secure, Engaged" with a sub-component of approximately 5,000 Canadian Rangers.[239][lower-alpha 2] In 2021, Canada's military expenditure totalled approximately $26.4 billion, or around 1.3 percent of the country's gross domestic product (GDP).[241] Canada's total military expenditure is expected to reach $32.7 billion by 2027.[242] Canada's military currently has over 3000 personnel deployed overseas in multiple operations, such as Operation Snowgoose in Cyprus, Operation Unifier supporting Ukraine, Operation Caribbe in the Caribbean Sea, and Operation Impact a coalition for the military intervention against ISIL.[243]

Provinces and territories

Canada is a federation composed of ten provinces and three territories. In turn, these may be grouped into four main regions: Western Canada, Central Canada, Atlantic Canada, and Northern Canada (Eastern Canada refers to Central Canada and Atlantic Canada together).[244] Provinces and territories have responsibility for social programs such as health care, education, and welfare,[245] as well as administration of justice (but not criminal law). Together, the provinces collect more revenue than the federal government, an almost unique structure among federations in the world. Using its spending powers, the federal government can initiate national policies in provincial areas, such as the Canada Health Act; the provinces can opt out of these, but rarely do so in practice. Equalization payments are made by the federal government to ensure reasonably uniform standards of services and taxation are kept between the richer and poorer provinces.[246]

The major difference between a Canadian province and a territory is that provinces receive their power and authority from the Constitution Act, 1867, whereas territorial governments have powers delegated to them by the Parliament of Canada.[247] The powers flowing from the Constitution Act, 1867 are divided between the federal government and the provincial governments to exercise exclusively.[248] As the division of powers between the federal government and the provinces is defined in the constitution, any changes require a constitutional amendment. The territories being creatures of the federal government, changes to their role and division of powers may be performed unilaterally by the Parliament of Canada.[249]

Economy

Canada has a highly developed mixed-market economy,[251][252] with the world's eighth-largest economy as of 2022, and a nominal GDP of approximately US$2.221 trillion.[253] It is one of the least corrupt countries in the world,[254] and is one of the world's largest trading nations, with a highly globalized economy.[255] Canada mixed economy ranks above the U.S. and most western European nations on The Heritage Foundation's Index of Economic Freedom,[256] and experiencing a relatively low level of income disparity.[257] The country's average household disposable income per capita is "well above" the OECD average.[258] The Toronto Stock Exchange is the ninth-largest stock exchange in the world by market capitalization, listing over 1,500 companies with a combined market capitalization of over US$2 trillion.[259]

In 2021, Canadian trade in goods and services reached $2.016 trillion.[260] Canada's exports totalled over $637 billion, while its imported goods were worth over $631 billion, of which approximately $391 billion originated from the United States.[260] In 2018, Canada had a trade deficit in goods of $22 billion and a trade deficit in services of $25 billion.[260]

Since the early 20th century, the growth of Canada's manufacturing, mining, and service sectors has transformed the nation from a largely rural economy to an urbanized, industrial one.[261] Like many other developed countries, the Canadian economy is dominated by the service industry, which employs about three-quarters of the country's workforce.[262] Among developed countries, Canada has an unusually important primary sector, of which the forestry and petroleum industries are the most prominent components.[263]

Canada's economic integration with the United States has increased significantly since World War II.[264] The Automotive Products Trade Agreement of 1965 opened Canada's borders to trade in the automobile manufacturing industry.[265] In the 1970s, concerns over energy self-sufficiency and foreign ownership in the manufacturing sectors prompted Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's Liberal government to enact the National Energy Program (NEP) and the Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA).[266] In the 1980s, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservatives abolished the NEP and changed the name of FIRA to Investment Canada, to encourage foreign investment.[267] The Canada – United States Free Trade Agreement (FTA) of 1988 eliminated tariffs between the two countries, while the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) expanded the free-trade zone to include Mexico in 1994 (later replaced by the Canada–United States–Mexico Agreement).[268] Canada has a strong cooperative banking sector, with the world's highest per-capita membership in credit unions.[269]

Canada is one of the few developed nations that are net exporters of energy.[263][270] Atlantic Canada possesses vast offshore deposits of natural gas, and Alberta also hosts large oil and gas resources. The vastness of the Athabasca oil sands and other assets results in Canada having a 13 percent share of global oil reserves, comprising the world's third-largest share after Venezuela and Saudi Arabia.[271] Canada is additionally one of the world's largest suppliers of agricultural products; the Canadian Prairies are one of the most important global producers of wheat, canola, and other grains.[272] The federal Department of Natural Resources provides statistics regarding its major exports; the country is a leading exporter of zinc, uranium, gold, nickel, platinoids, aluminum, steel, iron ore, coking coal, lead, copper, molybdenum, cobalt, and cadmium.[273] Many towns in northern Canada, where agriculture is difficult, are sustainable because of nearby mines or sources of timber. Canada also has a sizeable manufacturing sector centred in southern Ontario and Quebec, with automobiles and aeronautics representing particularly important industries.[274]

Science and technology

In 2019, Canada spent approximately $40.3 billion on domestic research and development, of which over $7 billion was provided by the federal and provincial governments.[275] As of 2020, the country has produced fifteen Nobel laureates in physics, chemistry, and medicine,[276] and was ranked fourth worldwide for scientific research quality in a major 2012 survey of international scientists.[277] It is furthermore home to the headquarters of a number of global technology firms.[278] Canada has one of the highest levels of Internet access in the world, with over 33 million users, equivalent to around 94 percent of its total 2014 population.[279] Canada was ranked 16th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021 and 17th in 2019 and 2020.[280][281][282]

.jpg.webp)

Some of the most notable scientific developments in Canada include the creation of the modern alkaline battery,[283] Insulin,[284] and the polio vaccine[285] and discoveries about the interior structure of the atomic nucleus.[286] Other major Canadian scientific contributions include the artificial cardiac pacemaker, mapping the visual cortex,[287][288] the development of the electron microscope,[289][290] plate tectonics, deep learning, multi-touch technology and the identification of the first black hole, Cygnus X-1.[291] Canada has a long history of discovery in genetics, which include stem cells, site-directed mutagenesis, T-cell receptor and the identification of the genes that cause Fanconi anemia, cystic fibrosis and early-onset Alzheimer's disease, among numerous other diseases.[288][292]

The Canadian Space Agency operates a highly active space program, conducting deep-space, planetary, and aviation research, and developing rockets and satellites.[293] Canada was the third country to design and construct a satellite after the Soviet Union and the United States, with the 1962 Alouette 1 launch.[294] Canada is a participant in the International Space Station (ISS), and is a pioneer in space robotics, having constructed the Canadarm, Canadarm2 and Dextre robotic manipulators for the ISS and NASA's Space Shuttle.[295] Since the 1960s, Canada's aerospace industry has designed and built numerous marques of satellite, including Radarsat-1 and 2, ISIS and MOST.[296] Canada has also produced one of the world's most successful and widely used sounding rockets, the Black Brant; over 1,000 Black Brants have been launched since the rocket's introduction in 1961.[297]

Demographics

The 2021 Canadian census enumerated a total population of 36,991,981, an increase of around 5.2 percent over the 2016 figure.[299] The main drivers of population growth are immigration and, to a lesser extent, natural growth.[300] Canada has one of the highest per-capita immigration rates in the world,[301] driven mainly by economic policy and also family reunification.[302][303] A record number of 405,000 immigrants were admitted to Canada in 2021.[304] New immigrants settle mostly in major urban areas in the country, such as Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver.[305] Canada also accepts large numbers of refugees, accounting for over 10 percent of annual global refugee resettlements; it resettled more than 28,000 in 2018.[306][307]

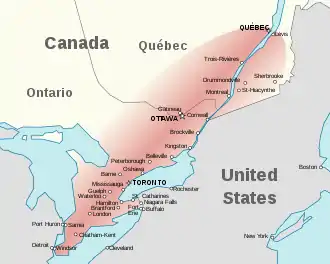

Canada's population density, at 4.2 inhabitants per square kilometre (11/sq mi), is among the lowest in the world.[299] Canada spans latitudinally from the 83rd parallel north to the 41st parallel north, and approximately 95 percent of the population is found south of the 55th parallel north.[308] About four-fifths of the population lives within 150 kilometres (93 mi) of the border with the contiguous United States.[309] The most densely populated part of the country, accounting for nearly 50 percent, is the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor in Southern Quebec and Southern Ontario along the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence River.[298][308]

The majority of Canadians (81.1 percent) live in family households, 12.1 percent report living alone, and those living with other relatives or unrelated persons reported at 6.8 percent.[310] Fifty-one percent of households are couples with or without children, 8.7% are single-parent households, 2.9% are multigenerational households, and 29.3% are single-person households.[310]

Largest metropolitan areas in Canada 2021 Canadian census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

| 1 | Toronto | Ontario | 6,202,225 | 11 | London | Ontario | 543,551 | ||

| 2 | Montreal | Quebec | 4,291,732 | 12 | Halifax | Nova Scotia | 465,703 | ||

| 3 | Vancouver | British Columbia | 2,642,825 | 13 | St. Catharines–Niagara | Ontario | 433,604 | ||

| 4 | Ottawa–Gatineau | Ontario–Quebec | 1,488,307 | 14 | Windsor | Ontario | 422,630 | ||

| 5 | Calgary | Alberta | 1,481,806 | 15 | Oshawa | Ontario | 415,311 | ||

| 6 | Edmonton | Alberta | 1,418,118 | 16 | Victoria | British Columbia | 397,237 | ||

| 7 | Quebec City | Quebec | 839,311 | 17 | Saskatoon | Saskatchewan | 317,480 | ||

| 8 | Winnipeg | Manitoba | 834,678 | 18 | Regina | Saskatchewan | 249,217 | ||

| 9 | Hamilton | Ontario | 785,184 | 19 | Sherbrooke | Quebec | 227,398 | ||

| 10 | Kitchener–Cambridge–Waterloo | Ontario | 575,847 | 20 | Kelowna | British Columbia | 222,162 | ||

Health

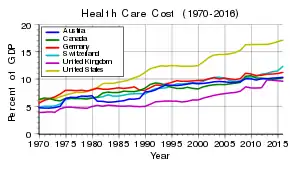

Healthcare in Canada is delivered through the provincial and territorial systems of publicly funded health care, informally called Medicare.[311][312] It is guided by the provisions of the Canada Health Act of 1984,[313] and is universal.[314] Universal access to publicly funded health services "is often considered by Canadians as a fundamental value that ensures national health care insurance for everyone wherever they live in the country."[315] Around 30 percent of Canadians' healthcare is paid for through the private sector.[316] This mostly pays for services not covered or partially covered by Medicare, such as prescription drugs, dentistry and optometry.[316] Approximately 65 to 75 percent of Canadians have some form of supplementary health insurance related to the aforementioned reasons; many receive it through their employers or utilizes secondary social service programs related to extended coverage for families receiving social assistance or vulnerable demographics, such as seniors, minors, and those with disabilities.[317][316]

In common with many other developed countries, Canada is experiencing a cost increase due to a demographic shift toward an older population, with more retirees and fewer people of working age. In 2006, the average age was 39.5 years;[318] it rose to 42.4 years by 2018[319] before falling slightly to 41.9 in 2021.[310] Life expectancy is 81.1 years.[320] A 2016 report by the chief public health officer found that 88 percent of Canadians, one of the highest proportions of the population among G7 countries, indicated that they "had good or very good health".[321] Eighty percent of Canadian adults self-report having at least one major risk factor for chronic disease: smoking, physical inactivity, unhealthy eating or excessive alcohol use.[322] Canada has one of the highest rates of adult obesity among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries attributing to approximately 2.7 million cases of diabetes (types 1 and 2 combined).[322] Four chronic diseases—cancer (leading cause of death), cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and diabetes—account for 65 percent of deaths in Canada.[323][324]

In 2021, the Canadian Institute for Health Information reported that healthcare spending reached $308 billion, or 12.7 percent of Canada's GDP for that year.[325] Canada's per-capita spending on health expenditures ranked 4th among health-care systems in the OECD.[326] Canada has performed close to, or above the average on the majority of OECD health indicators since the early 2000s.[327] Although Canada consistently ranks above the average on OECD indicators for wait-times and access to care, with average scores for quality of care and use of resources.[328] The Commonwealth Funds 2021 report comparing the healthcare systems of the 11 most developed countries ranked Canada second -to-last.[329] Identified weaknesses were comparatively higher infant mortality rate, the prevalence of chronic conditions, long wait times, poor availability of after-hours care, and a lack of prescription drugs and dental coverage.[329]

Education

Education in Canada is for the most part provided publicly, funded and overseen by federal, provincial, and local governments.[330] Education is within provincial jurisdiction and the curriculum is overseen by the province.[331][332] Education in Canada is generally divided into primary education, followed by secondary education and post-secondary. Education in both English and French is available in most places across Canada.[333] Canada has a large number of universities, almost all of which are publicly funded.[334] Established in 1663, Université Laval is the oldest post-secondary institution in Canada.[335] The largest university is the University of Toronto with over 85,000 students.[336] Four universities are regularly ranked among the top 100 world-wide, namely University of Toronto, University of British Columbia, McGill University and McMaster University, with a total of 18 universities ranked in the top 500 worldwide.[337]

According to a 2019 report by the OECD, Canada is one of the most educated countries in the world;[338] the country ranks first worldwide in the number of adults having tertiary education, with over 56 percent of Canadian adults having attained at least an undergraduate college or university degree.[338] Canada spends about 5.3 percent of its GDP on education.[339] The country invests heavily in tertiary education (more than US$20,000 per student).[340] As of 2014, 89 percent of adults aged 25 to 64 have earned the equivalent of a high-school degree, compared to an OECD average of 75 percent.[341]

The mandatory education age ranges between 5–7 to 16–18 years,[342] contributing to an adult literacy rate of 99 percent.[319] Just over 60,000 children are homeschooled in the country as of 2016. The Programme for International Student Assessment indicates Canadian students perform well above the OECD average, particularly in mathematics, science, and reading,[343][344] ranking the overall knowledge and skills of Canadian 15-year-olds as the sixth-best in the world, although these scores have been declining in recent years. Canada is a well-performing OECD country in reading literacy, mathematics, and science with the average student scoring 523.7, compared with the OECD average of 493 in 2015.[345][346]

Ethnicity

English Irish Scottish French German Chinese Indian Ukrainian |

Métis Acadian Mennonite Inuit Cree Ojibway Dene Heiltsuk |

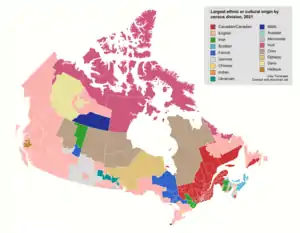

According to the 2021 Canadian census, over 450 "ethnic or cultural origins" were self-reported by Canadians.[347] The major panethnic groups chosen were; European (52.5%), North American (22.9%), Asian (19.3%), North American Indigenous (6.1%), African (3.8%), Latin, Central and South American (2.5%), Caribbean (2.1%), Oceanian (0.3%), and Other (6%).[347][348] Statistics Canada reports that 35.5% of the population reported multiple ethnic origins, thus the overall total is greater than 100%.[347]

The country's ten largest self-reported specific ethnic or cultural origins in 2021 were Canadian[lower-alpha 3] (accounting for 15.6 percent of the population), followed by English (14.7 percent), Irish (12.1 percent), Scottish (12.1 percent), French (11.0 percent), German (8.1 percent), Chinese (4.7 percent), Italian (4.3 percent), Indian (3.7 percent), and Ukrainian (3.5 percent).[352]

Of the 36.3 million people enumerated in 2021 approximately 25.4 million reported being "white", representing 69.8 percent of the population.[353] The indigenous population representing 5 percent or 1.8 million individuals, grew by 9.4 percent compared to the non-Indigenous population, which grew by 5.3 percent from 2016 to 2021.[354] One out of every four Canadians or 26.5 percent of the population belonged to a non-White and non-Indigenous visible minority,[355][lower-alpha 4] the largest of which in 2021 were South Asian (2.6 million people; 7.1 percent), Chinese (1.7 million; 4.7 percent) and Black (1.5 million; 4.3 percent).[353]

Between 2011 and 2016, the visible minority population rose by 18.4 percent.[357] In 1961, less than two percent of Canada's population (about 300,000 people) were members of visible minority groups.[358] The 2021 Census indicated that 8.3 million people, or almost one-quarter (23.0 percent) of the population reported themselves as being or having been a landed immigrant or permanent resident in Canada—above the 1921 Census previous record of 22.3 percent.[359] In 2021 India, China, and the Philippines were the top three countries of origin for immigrants moving to Canada.[360]

Languages

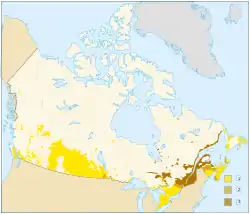

A multitude of languages are used by Canadians, with English and French (the official languages) being the mother tongues of approximately 54 percent and 19 percent of Canadians, respectively.[362] As of the 2021 Census, just over 7.8 million Canadians listed a non-official language as their mother tongue. Some of the most common non-official first languages include Mandarin (679,255 first-language speakers), Punjabi (666,585), Cantonese (553,380), Spanish (538,870), Arabic (508,410), Tagalog (461,150), Italian (319,505), and German (272,865).[362] Canada's federal government practices official bilingualism, which is applied by the commissioner of official languages in consonance with section 16 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the federal Official Languages Act. English and French have equal status in federal courts, Parliament, and in all federal institutions. Citizens have the right, where there is sufficient demand, to receive federal government services in either English or French and official-language minorities are guaranteed their own schools in all provinces and territories.[363]

The 1977 Charter of the French Language established French as the official language of Quebec.[364] Although more than 82 percent of French-speaking Canadians live in Quebec, there are substantial Francophone populations in New Brunswick, Alberta, and Manitoba; Ontario has the largest French-speaking population outside Quebec.[365] New Brunswick, the only officially bilingual province, has a French-speaking Acadian minority constituting 33 percent of the population.[366] There are also clusters of Acadians in southwestern Nova Scotia, on Cape Breton Island, and through central and western Prince Edward Island.[367]

Other provinces have no official languages as such, but French is used as a language of instruction, in courts, and for other government services, in addition to English. Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec allow for both English and French to be spoken in the provincial legislatures, and laws are enacted in both languages. In Ontario, French has some legal status, but is not fully co-official.[368] There are 11 Indigenous language groups, composed of more than 65 distinct languages and dialects.[369] Several Indigenous languages have official status in the Northwest Territories.[370] Inuktitut is the majority language in Nunavut, and is one of three official languages in the territory.[371]

Additionally, Canada is home to many sign languages, some of which are Indigenous.[372] American Sign Language (ASL) is spoken across the country due to the prevalence of ASL in primary and secondary schools.[373] Due to its historical relation to the francophone culture, Quebec Sign Language (LSQ) is spoken primarily in Quebec, although there are sizeable Francophone communities in New Brunswick, Ontario and Manitoba.[374]

Religion

The "Fundamental Freedoms" section of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms states:[375]

- 2. Everyone has the following fundamental freedoms:

- (a) freedom of conscience and religion;

- (b) freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication;

- (c) freedom of peaceful assembly; and

- (d) freedom of association.

Canada is religiously diverse, encompassing a wide range of beliefs and customs. Although the Constitution of Canada refers to God and the monarch carries the title of "Defender of the Faith", Canada has no official church, and the government is officially committed to religious pluralism.[376] Freedom of religion in Canada is a constitutionally protected right, allowing individuals to assemble and worship without limitation or interference.[377]

The practice of religion is generally considered a private matter throughout society and the state.[378] With Christianity in decline after having once been central and integral to Canadian culture and daily life,[379] Canada has become a post-Christian, secular state.[380][381][382][383] The majority of Canadians consider religion to be unimportant in their daily lives,[384] but still believe in God.[385]

According to the 2021 census, Christianity is the largest religion in Canada, with Roman Catholics having the most adherents. Christians, representing 53.3% of the population in 2021, are followed by people having irreligion/no religion at 34.6%.[386] Other faiths include Islam (4.9%), Hinduism (2.3%), Sikhism (2.1%), Buddhism (1.0%), Judaism (0.9%), and Indigenous spirituality (0.2%).[387][388] Rates of religious adherence are steadily decreasing.[389][390]

Culture

Canada's culture draws influences from its broad range of constituent nationalities, and policies that promote a "just society" are constitutionally protected.[391][392][393] Canada has placed emphasis on equality and inclusiveness for all its people.[394] The official state policy of multiculturalism is often cited as one of Canada's significant accomplishments,[395] and a key distinguishing element of Canadian identity.[396][397] In Quebec, cultural identity is strong, and there is a French Canadian culture that is distinct from English Canadian culture.[398] As a whole, Canada is in theory a cultural mosaic of regional ethnic subcultures.[399]

Canada's approach to governance emphasizing multiculturalism, which is based on selective immigration, social integration, and suppression of far-right politics, has wide public support.[400] Government policies such as publicly funded health care, higher taxation to redistribute wealth, the outlawing of capital punishment, strong efforts to eliminate poverty, strict gun control, a social liberal attitude toward women's rights (like pregnancy termination) and LGBTQ rights, legalized euthanasia and cannabis use are indicators of Canada's political and cultural values.[401][402][403] Canadians also identify with the country's foreign aid policies, peacekeeping roles, the National park system and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[404][405]

Historically, Canada has been influenced by British, French, and Indigenous cultures and traditions. Through their language, art and music, Indigenous peoples continue to influence the Canadian identity.[406] During the 20th century, Canadians with African, Caribbean and Asian nationalities have added to the Canadian identity and its culture.[407] Canadian humour is an integral part of the Canadian identity and is reflected in its folklore, literature, music, art, and media. The primary characteristics of Canadian humour are irony, parody, and satire.[408]

Symbols

Themes of nature, pioneers, trappers, and traders played an important part in the early development of Canadian symbolism.[410] Modern symbols emphasize the country's geography, cold climate, lifestyles and the Canadianization of traditional European and Indigenous symbols.[411] The use of the maple leaf as a Canadian symbol dates to the early 18th century. The maple leaf is depicted on Canada's current and previous flags, and on the Arms of Canada.[412] Canada's official tartan, known as the "maple leaf tartan", has four colours that reflect the colours of the maple leaf as it changes through the seasons—green in the spring, gold in the early autumn, red at the first frost, and brown after falling.[413] The Arms of Canada are closely modelled after the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom with French and distinctive Canadian elements replacing or added to those derived from the British version.[414]

Other prominent symbols include the national motto "A mari usque ad mare" ("From Sea to Sea"),[415] the sports of ice hockey and lacrosse, the beaver, Canada goose, common loon, Canadian horse, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Canadian Rockies,[412] and more recently the totem pole and Inuksuk.[416] Material items such as Canadian beer, maple syrup, tuques, canoes, nanaimo bars, butter tarts and the Quebec dish of poutine are defined as uniquely Canadian.[416][417] Canadian coins feature many of these symbols: the loon on the $1 coin, the Arms of Canada on the 50¢ piece, the beaver on the nickel.[418] The penny, removed from circulation in 2013, featured the maple leaf.[419] An image of the previous monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, appears on $20 bank notes, and on the obverse of all current Canadian coins.[418]

Literature

Canadian literature is often divided into French- and English-language literatures, which are rooted in the literary traditions of France and Britain, respectively.[420] The earliest Canadian narratives were of travel and exploration.[421] This progressed into three major themes that can be found within historical Canadian literature: nature, frontier life, Canada's position within the world, all three of which tie into the garrison mentality.[422] In recent decades, Canada's literature has been strongly influenced by immigrants from around the world.[423] Since the 1980s, Canada's ethnic and cultural diversity has been openly reflected in its literature.[424] By the 1990s, Canadian literature was viewed as some of the world's best.[424]

Numerous Canadian authors have accumulated international literary awards,[425] including novelist, poet, and literary critic Margaret Atwood, who received two Booker Prizes;[426] Nobel laureate Alice Munro, who has been called the best living writer of short stories in English;[427] and Booker Prize recipient Michael Ondaatje, who wrote the novel The English Patient, which was adapted as a film of the same name that won the Academy Award for Best Picture.[428] L. M. Montgomery produced a series of children's novels beginning in 1908 with Anne of Green Gables.[429]

Media

Canada's media is highly autonomous, uncensored, diverse and very regionalized.[430][431] The Broadcasting Act declares "the system should serve to safeguard, enrich and strengthen the cultural, political, social and economic fabric of Canada".[432] Canada has a well-developed media sector, but its cultural output—particularly in English films, television shows, and magazines—is often overshadowed by imports from the United States.[433] As a result, the preservation of a distinctly Canadian culture is supported by federal government programs, laws, and institutions such as the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC).[434]

Canadian mass media, both print and digital and in both official languages, is largely dominated by a "handful of corporations".[435] The largest of these corporations is the country's national public broadcaster, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, which also plays a significant role in producing domestic cultural content, operating its own radio and TV networks in both English and French.[436] In addition to the CBC, some provincial governments offer their own public educational TV broadcast services as well, such as TVOntario and Télé-Québec.[437]

Non-news media content in Canada, including film and television, is influenced both by local creators as well as by imports from the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and France.[438] In an effort to reduce the amount of foreign-made media, government interventions in television broadcasting can include both regulation of content and public financing.[439] Canadian tax laws limit foreign competition in magazine advertising.[440]

Visual arts

Art in Canada is marked by thousands of years of habitation by its indigenous peoples.[441] Historically, the Catholic Church was the primary patron of art in New France and early Canada, especially Quebec,[442] and in later times, artists have combined British, French, Indigenous and American artistic traditions, at times embracing European styles while working to promote nationalism.[443] The nature of Canadian art reflects these diverse origins, as artists have taken their traditions and adapted these influences to reflect the reality of their lives in Canada.[444]

The Canadian government has played a role in the development of Canadian culture through the department of Canadian Heritage, by giving grants to art galleries,[445] as well as establishing and funding art schools and colleges across the country, and through the Canada Council for the Arts (established in 1957), the national public arts funder, helping artists, art galleries and periodicals, and thus contributing to the development of Canada's cultural works.[446] Since the 1950s, works of Inuit art have been given as gifts to foreign dignitaries by the Canadian government.[447]

Canadian visual art has been dominated by figures such as painter Tom Thomson and by the Group of Seven.[448] The Group of Seven were painters with a nationalistic and idealistic focus, who first exhibited their distinctive works in May 1920. Though referred to as having seven members, five artists—Lawren Harris, A. Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer, J. E. H. MacDonald, and Frederick Varley—were responsible for articulating the group's ideas. They were joined briefly by Frank Johnston and by commercial artist Franklin Carmichael. A. J. Casson became part of the group in 1926.[449] Associated with the group was another prominent Canadian artist, Emily Carr, known for her landscapes and portrayals of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast.[450]

Music

Canadian music reflects a variety of regional scenes.[451] Canada has developed a vast music infrastructure that includes church halls, chamber halls, conservatories, academies, performing arts centres, record companies, radio stations and television music video channels.[452] Government support programs, such as the Canada Music Fund, assist a wide range of musicians and entrepreneurs who create, produce and market original and diverse Canadian music.[453] The Canadian music industry is the sixth-largest in the world, producing internationally renowned composers, musicians and ensembles.[454] Music broadcasting in the country is regulated by the CRTC.[455] The Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences presents Canada's music industry awards, the Juno Awards, which were first awarded in 1970.[456] The Canadian Music Hall of Fame, established in 1976, honours Canadian musicians for their lifetime achievements.[457]

Patriotic music in Canada dates back over 200 years as a distinct category from British patriotism, preceding Canadian Confederation by over 50 years. The earliest work of patriotic music in Canada, "The Bold Canadian", was written in 1812.[458] "The Maple Leaf Forever" written in 1866, was a popular patriotic song throughout English Canada and for many years served as an unofficial national anthem.[459] The official national anthem, "O Canada", was originally commissioned by the lieutenant governor of Quebec, Théodore Robitaille, for the 1880 St. Jean-Baptiste Day ceremony and was officially adopted in 1980.[460] Calixa Lavallée wrote the music, which was a setting of a patriotic poem composed by the poet and judge Sir Adolphe-Basile Routhier. The text was originally only in French before it was adapted into English in 1906.[461]

Sports

The roots of organized sports in Canada date back to the 1770s,[462] culminating in the development and popularization of the major professional games of ice hockey, lacrosse, curling, basketball, baseball, association football and Canadian football.[463] Canada's official national sports are ice hockey and lacrosse.[464] Other sports such as volleyball, skiing, cycling, swimming, badminton, tennis, bowling and the study of martial arts are all widely enjoyed at the youth and amateur levels.[465] Great achievements in Canadian sports are recognized by Canada's Sports Hall of Fame,[466] while the Lou Marsh Trophy is awarded annually to Canada's top athlete by a panel of journalists.[467] There are numerous other sport "halls of fame" in Canada, such as the Hockey Hall of Fame.[466]

Canada shares several major professional sports leagues with the United States.[468] Canadian teams in these leagues include seven franchises in the National Hockey League, as well as three Major League Soccer teams and one team in each of Major League Baseball and the National Basketball Association. Other popular professional competitions include the Canadian Football League, National Lacrosse League, the Canadian Premier League, and the various curling tournaments sanctioned and organized by Curling Canada.[469]

Canada has enjoyed success both at the Winter Olympics and at the Summer Olympics,[470] though particularly the Winter Games as a "winter sports nation", and has hosted several high-profile international sporting events such as the 1976 Summer Olympics,[471] the 1988 Winter Olympics,[472] the 2010 Winter Olympics[473][474] and the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup.[475] Most recently, Canada hosted the 2015 Pan American Games and 2015 Parapan American Games in Toronto, the former being one of the largest sporting event hosted by the country.[476] The country is scheduled to co-host the 2026 FIFA World Cup alongside Mexico and the United States.[477]

See also

- Index of Canada-related articles

- Outline of Canada

- Topics by provinces and territories

Notes

- "Brokerage politics: A Canadian term for successful big tent parties that embody a pluralistic catch-all approach to appeal to the median Canadian voter ... adopting centrist policies and electoral coalitions to satisfy the short-term preferences of a majority of electors who are not located on the ideological fringe."[167][168] "The traditional brokerage model of Canadian politics leaves little room for ideology"[169][170][171][172]

- "The Royal Canadian Navy is composed of approximately 8,400 full-time sailors and 5,100 part-time sailors. The Canadian Army is composed of approximately 22,800 full-time soldiers, 18,700 Reservists, and 5,000 Canadian Rangers. The Royal Canadian Air Force is composed of approximately 13,000 Regular Force personnel and 2,400 Air Reserve personnel."[240]