Fleur-de-lis

The fleur-de-lis, also spelled fleur-de-lys (plural fleurs-de-lis or fleurs-de-lys),[pron 1] is a lily (in French, fleur and lis mean 'flower' and 'lily' respectively) that is used as a decorative design or symbol.

.svg.png.webp)

The fleur-de-lis has been used in the heraldry of numerous European nations, but is particularly associated with France, notably during its monarchical period. The fleur-de-lis became "at one and the same time, religious, political, dynastic, artistic, emblematic, and symbolic," especially in French heraldry.[4] The fleur-de-lis has been used by French royalty and throughout history to represent saints of France. In particular, the Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph are often depicted with a lily.

The fleur-de-lis is represented in Unicode at U+269C ⚜ in the Miscellaneous Symbols block.

Origin

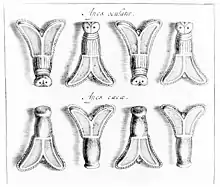

The fleur de lis is widely thought to be a stylized version of the species Iris pseudacorus, or Iris florentina.[5][6] However, the lily (genus lilium, family Liliaceae) and the iris (family Iridaceae) are two different plants, phylogenetically and taxonomically unrelated. Lily (in Italian: giglio) is the name usually associated with the stylized flower in the Florentine heraldic devices.

Decorative ornaments that resemble the fleur-de-lis have appeared in artwork from the earliest human civilizations. According to Pierre-Augustin Boissier de Sauvages, an 18th-century French naturalist and lexicographer:[7]

The old fleurs-de-lis, especially the ones found in our first kings' sceptres, have a lot less in common with ordinary lilies than the flowers called flambas [in Occitan], or irises, from which the name of our own fleur-de-lis may derive. What gives some colour of truth to this hypothesis that we already put forth, is the fact that the French or Franks, before entering Gaul itself, lived for a long time around the river named Lys in the Flanders. Nowadays, this river is still bordered with an exceptional number of irises —as many plants grow for centuries in the same places—: these irises have yellow flowers, which is not a typical feature of lilies but fleurs-de-lis. It was thus understandable that our kings, having to choose a symbolic image for what later became a coat of arms, set their minds on the iris, a flower that was common around their homes, and is also as beautiful as it was remarkable. They called it, in short, the fleur-de-lis, instead of the flower of the river of lis. This flower, or iris, looks like our fleur-de-lis not just because of its yellow colour but also because of its shape: of the six petals, or leaves, that it has, three of them are alternatively straight and meet at their tops. The other three on the opposite, bend down so that the middle one seems to make one with the stalk and only the two ones facing out from left and right can clearly be seen, which is again similar with our fleurs-de-lis, that is to say exclusively the one from the river Luts whose white petals bend down too when the flower blooms.

The heraldist François Velde is known to have expressed the same opinion:[9]

However, a hypothesis ventured in the 17th c. sounds very plausible to me. One species of wild iris, the Iris pseudacorus, yellow flag in English, is yellow and grows in marshes (cf. the azure field, for water). Its name in German is Lieschblume (also gelbe Schwertlilie), but Liesch was also spelled Lies and Leys in the Middle Ages. It is easy to imagine that, in Northern France, the Lieschblume would have been called 'fleur-de-lis'. This would explain the name and the formal origin of the design, as a stylized yellow flag. There is a fanciful legend about Clovis which links the yellow flag explicitly with the French coat of arms.[9]

Sauvages' hypothesis seems to be supported by the archaic English spelling fleur-de-luce[10] and by the Luts's variant name Lits.

Alternative derivations

Another (debated) hypothesis is that the symbol derives from the Frankish Angon.[11] Note that the angon, or sting, was a typical Frankish throwing spear.[11]

A possibly derived symbol of Frankish royalty was the bee, of similar shape, as found in the burial of Childric I, whose royal see of power over the Salian Franks was based over the valley of the Lys.

Other imaginative explanations include the shape having been developed from the image of a dove descending, which is the symbol of the Holy Ghost.

The golden bees/flies discovered in the tomb of Childeric I in 1653

The golden bees/flies discovered in the tomb of Childeric I in 1653 Seal of Philippe Auguste (1180)

Seal of Philippe Auguste (1180)_King_Hywel_cropped.jpg.webp) Laws of Hywel Dda, Welsh king 'Hywel the Good' holding a Fleur De Lis scepter (mid-13th century)

Laws of Hywel Dda, Welsh king 'Hywel the Good' holding a Fleur De Lis scepter (mid-13th century)

Ancient usages

It has consistently been used as a royal emblem, though different cultures have interpreted its meaning in varying ways. Gaulish coins show the first Western designs which look similar to modern fleurs-de-lis.[12] In the East it was found on the gold helmet of a Scythian king uncovered at the Ak-Burun kurgan and conserved in Saint Petersburg's Hermitage Museum.[13]

There is also a statue of Kanishka the Great, the emperor of the Kushan dynasty in 127–151 AD, in the Mathura Museum in India, with four modern Fleurs-de-lis symbols in a square emblem repeated twice on the bottom end of his smaller sword.

Royal symbolism

Frankish to the French monarchy

The graphic evolution of crita to fleur-de-lis was accompanied by textual allegory. By the late 13th century, an allegorical poem by Guillaume de Nangis (d. 1300), written at Joyenval Abbey in Chambourcy, relates how the golden lilies on an azure ground were miraculously substituted for the crescents on Clovis' shield, a projection into the past of contemporary images of heraldry.

The fleur-de-lis' symbolic origins with French monarchs may stem from the baptismal lily used in the crowning of King Clovis I.[14] The French monarchy may have adopted the Fleur-de-lis for its royal coat of arms as a symbol of purity to commemorate the conversion of Clovis I,[15] and a reminder of the Fleur-de-lis ampulla that held the oil used to anoint the king. So, the fleur-de-lis stood as a symbol of the king's divinely approved right to rule. The thus "anointed" kings of France later maintained that their authority was directly from God. A legend enhances the mystique of royalty by informing us that a vial of oil—the Holy Ampulla—descended from Heaven to anoint and sanctify Clovis as King,[16] descending directly on Clovis or perhaps brought by a dove to Saint Remigius. One version explains that an angel descended with the Fleur-de-lis ampulla to anoint the king.[17] Another story tells of Clovis putting a flower in his helmet just before his victory at the Battle of Vouillé.[9] Through this propagandist connection to Clovis, the fleur-de-lis has been taken in retrospect to symbolize all the Christian Frankish kings, most notably Charlemagne.[18]

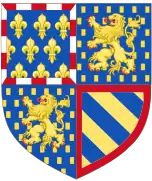

In the 14th-century French writers asserted that the monarchy of France, which developed from the Kingdom of the West Franks, could trace its heritage back to the divine gift of royal arms received by Clovis. This story has remained popular, even though modern scholarship has established that the fleur-de-lis was a religious symbol before it was a true heraldic symbol.[19] Along with true lilies, it was associated with the Virgin Mary, and in the 12th century Louis VI and Louis VII started to use the emblem, on sceptres for example, so connecting their rulership with this symbol of saintliness and divine right. Louis VII ordered the use of fleur-de-lis clothing in his son Philip's coronation in 1179,[20] while the first visual evidence of clearly heraldic use dates from 1211: a seal showing the future Louis VIII and his shield strewn with the "flowers".[21] Until the late 14th century the French royal coat of arms was Azure semé-de-lis Or (a blue shield "sown" (semé) with a scattering of small golden fleurs-de-lis), but Charles V of France changed the design from an all-over scattering to a group of three in about 1376.[a][b] These two coats are known in heraldic terminology as France Ancient and France Modern, respectively.

In the reign of King Louis IX (St. Louis) the three petals of the flower were said to represent faith, wisdom and chivalry, and to be a sign of divine favour bestowed on France.[22] During the next century, the 14th, the tradition of Trinity symbolism was established in France, and then spread elsewhere.

In 1328, King Edward III of England inherited a claim to the crown of France, and in about 1340 he quartered France Ancient with the arms of Plantagenet, as "arms of pretence". [c] After the kings of France adopted France Modern, the kings of England adopted the new design as quarterings from about 1411.[23] The monarchs of England (and later of Great Britain) continued to quarter the French arms until 1801, when George III abandoned his formal claim to the French throne.

King Charles VII ennobled Joan of Arc's family on 29 December 1429 with an inheritable symbolic denomination. The Chamber of Accounts in France registered the family's designation to nobility on 20 January 1430. The grant permitted the family to change their surname to du Lys.

France Moderne

France moderne remained the French royal standard, and with a white background was the French national flag until the French Revolution, when it was replaced by the tricolor of modern-day France. The fleur-de-lis was restored to the French flag in 1814, but replaced once again after the revolution against Charles X of France in 1830.[d] In a very strange turn of events after the end of the Second French Empire, where a flag apparently influenced the course of history, Henri, comte de Chambord, was offered the throne as King of France, but he agreed only if France gave up the tricolor and brought back the white flag with fleurs-de-lis.[24] His condition was rejected and France became a republic.

Other European monarchs and rulers

Fleurs-de-lis feature prominently in the Crown Jewels of England and Scotland. In English heraldry, they are used in many different ways, and can be the cadency mark of the sixth son. Additionally, it features in a large number of royal arms of the House of Plantagenet, from the 13th century onwards to the early Tudors (Elizabeth of York and the de la Pole family).

The tressure flory–counterflory (flowered border) has been a prominent part of the design of the Scottish royal arms and Royal Standard since James I of Scotland.[e]

The treasured fleur-de-luce he claims

To wreathe his shield, since royal James

—Sir Walter Scott, The Lay of the Last Minstrel[25]

In Italy, fleurs-de-lis have been used for some papal crowns[g] and coats of arms, the Farnese Dukes of Parma, and by some doges of Venice.

The fleur-de-lis was also the symbol of the House of Kotromanić, a ruling house in medieval Bosnia allegedly in recognition of the Capetian House of Anjou, where the flower is thought of as a Lilium bosniacum.[h] Today, fleur-de-lis is a national symbol of Bosniaks.[i]

Other countries include Spain in recognition of rulers from the House of Bourbon. Coins minted in 14th-century Romania, from the region that was the Principality of Moldova at the time, ruled by Petru I Mușat, carry the fleur-de-lis symbol.[26]

As a dynastic emblem it has also been very widely used: not only by noble families but also, for example, by the Fuggers, a medieval banking family.

Three fleurs-de-lis appeared in the personal coat of arms of Grandmaster Alof de Wignacourt who ruled the Malta between 1601 and 1622. His nephew Adrien de Wignacourt, who was Grandmaster himself from 1690 to 1697, also had a similar coat of arms with three fleurs-de-lis.

Usage by country

Albania

In Albania, fleur-de-lys (alb: Lulja e Zambakut) has been always associated with the Noble House of Topia. According to Karl Hopf, Andrea Thopia, as told by Gjon Muzaka (fl. 1510), had fallen in love with the daughter of Robert of Naples when her ship, en route to the Principality of the Morea to be wed with the bailli, had stopped at Durazzo where they met. Andrea abducted and married her, and they had two sons, Karl and George. King Robert, enraged, under the pretext of reconciliation had the couple invited to Naples where he had them executed. During Karl's Reign the Fleur-de-lys became a symbol implying his royal blood. After Ottoman's Conquest of Albania the symbol was removed by the converted Toptani Family a muslim branch of Topia Family. [27]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The golden lily is a traditional symbol of the Bosniak people.[28] The coat of arms of the medieval Kingdom of Bosnia contained six fleurs-de-lis, understood as the native Bosnian or Golden Lily, Lilium bosniacum.[29] This emblem was revived in 1992 as a national symbol of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and was the flag of Bosnia-Herzegovina from 1992 to 1998.[30] The state insignia were changed in 1999. The former flag of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina contains a fleur-de-lis alongside the Croatian chequy. Fleurs also appear in the flags and arms of many cantons, municipalities, cities and towns. It is still used as official insignia of the Bosniak Regiment of the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[31]

Canada

The Royal Banner of France or "Bourbon Flag" symbolizing royal France, was the most commonly used flag in New France.[32][33] The "Bourbon Flag" has three gold fleur-de-lis on a dark blue field arranged two and one.[34] The fleur-de-lys was also seen on New France's currency often referred to as "card money".[35] The white Royal Banner of France was used by the military of New France and was seen on naval vessels and forts of New France.[36] After the fall of New France to the British Empire the fleur-de-lys remained visible on churches and remained part of French cultural symbolism.[37] There are many French-speaking Canadians for whom the fleur-de-lis remains a symbol of their French cultural identity. Franco-Ontarians, Franco-Ténois and Franco-Albertans, feature the fleur-de-lis prominently on their flags.

The Fleur-de-lys, as a traditional Royal symbol in Canada, has been incorporated into many national symbols, provincial symbols and municipal symbols, The Canadian Red Ensign that served as the nautical flag and civil ensign for Canada from 1892 to 1965 and later as an informal flag of Canada before 1965 featured the traditional number of three golden fleur-de-lys on a blue background.[38] The Arms of Canada throughout its variations has used fleur-de-lys, beginning in 1921 and subsequent various has featuring the blue "Bourbon Flag" in two locations within arms.[39] The Canadian Royal cypher and the Arms of Canada feature St Edward's Crown that displays five cross pattée and four fleur-de-lys.[40] Fleur-de-lys are also featured on the personal flag used by the Queen of Canada.[41] The fleur-de-lis is featured on the flag of Quebec, known as the Fleurdelisé, as well as the flags of the cities of Montreal, Sherbrooke and Trois-Rivières.

France

While the fleur-de-lis has appeared on countless European coats of arms and flags over the centuries, it is particularly associated with the French monarchy in a historical context and continues to appear in the arms of the king of Spain (from the French House of Bourbon), the grand duke of Luxembourg, and members of the House of Bourbon. It remains an enduring symbol of France which appears on French postage stamps, although it has never been adopted officially by any of the French republics. According to French historian Georges Duby, the three petals represent the three medieval social estates: the commoners, the nobility, and the clergy.[42]

Although the origin of the fleur-de-lis is unclear, it has retained an association with French nobility. It is widely used in French city emblems as in the coat of arms of the city of Lille, Saint-Denis, Brest, Clermont-Ferrand, Boulogne-Billancourt, and Calais. Some cities that had been particularly faithful to the French Crown were awarded a heraldic augmentation of two or three fleurs-de-lis on the chief of their coat of arms; such cities include Paris, Lyon, Toulouse, Bordeaux, Reims, Le Havre, Angers, Le Mans, Aix-en-Provence, Tours, Limoges, Amiens, Orléans, Rouen, Argenteuil, Poitiers, Chartres, and Laon, among others. The fleur-de-lis was the symbol of Île-de-France, the core of the French kingdom. It has appeared on the coat-of-arms of other historical provinces of France including Burgundy, Anjou, Picardy, Berry, Orléanais, Bourbonnais, Maine, Touraine, Artois, Dauphiné, Saintonge, and the County of La Marche. Many of the current French departments use the symbol on their coats-of-arms to express this heritage.

Italy

In Italy, the fleur de lis, called giglio bottonato (it), is mainly known from the crest of the city of Florence. In the Florentine fleurs-de-lis,[f] the stamens are always posed between the petals. Originally argent (silver or white) on gules (red) background, the emblem became the standard of the imperial party in Florence (parte ghibellina), causing the town government, which maintained a staunch Guelph stance, being strongly opposed to the imperial pretensions on city states, to reverse the color pattern to the final gules lily on argent background.[43] This heraldic charge is often known as the Florentine lily to distinguish it from the conventional (stamen-not-shown) design. As an emblem of the city, it is therefore found in icons of Zenobius, its first bishop,[44] and associated with Florence's patron Saint John the Baptist in the Florentine fiorino. Several towns subjugated by Florence or founded within the territory of the Florentine Republic adopted a variation of the Florentine lily in their crests, often without the stamens.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania and successor countries

The fleur-de-lis was used in Grand Duchy of Lithuania as part of the Sapieha family coat of arms

The design of the arms of Jurbarkas is believed to originate from the arms of the Sapieha house, a noble family from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania which was responsible for Jurbarkas receiving city rights and a coat of arms in 1611.[45][46]

The three fleurs-de-lis design on the Jurbarkas coat of arms was abolished during the final years of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but officially restored in 1993 after the independence of present-day Lithuania. Before restoration, several variant designs, such as using one over two fleurs-de-lis, had been restored and abolished. The original two over one version was briefly readopted in 1970 during the Soviet period, but abolished that same year.[47] There is also a Belarusian Scouting and Guiding organization that, while preserving the traditions of the past, uses a fleur-de-lis as a symbol.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, a fleur-de-lis has appeared in the official arms of the Norroy King of Arms for hundreds of years. A silver fleur-de-lis on a blue background is the arms of the Barons Digby.[48]

In English and Canadian heraldry the fleur-de-lis is the cadence mark of a sixth son.[49]

It can also be found on the arms of the Scottish clan Chiefs of both Carruthers; Gules two engrailed chevrons between three fleur-d-lis Or and the Brouns/Browns: Gules a chevron between three fleur d-lis Or.[50][51]

United States

Fleurs-de-lis crossed the Atlantic along with Europeans going to the New World, especially with French settlers. Their presence on North American flags and coats of arms usually recalls the involvement of French settlers in New France of the town or region concerned, and in some cases the persisting presence there of a population descended from such settlers.

_Shoulder_Sleeve_Insignia.jpg.webp)

In the US, the fleur-de-lis symbols tend to be along or near the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. These are areas of strong French colonial empire settlement. Some of the places that have it in their flag or seal are the cities of Baton Rouge, Detroit, Lafayette, Louisville, Mobile, New Orleans, Ocean Springs and St. Louis[m]. On 9 July 2008, Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal signed a bill into law making the fleur-de-lis an official symbol of the state.[52] Following Hurricane Katrina on 29 August 2005, the fleur-de-lis has been widely used in New Orleans and throughout Louisiana, as a symbol of grassroots support for New Orleans' recovery.[53] The coat of arms of St. Augustine, Florida has a fleur-de-lis on the first quarter, due to its connection with Huguenots. Several counties have flags and seals based on pre-1801 British royal arms also includes fleur-de-lis symbols. They are King George County, Virginia and Prince George's County, Somerset County and Kent County in Maryland. It has also become the symbol for the identity of the Cajuns and Louisiana Creole people, and their French heritage.

Elsewhere

In Brazil, the city of Joinville has three fleurs-de-lis surmounted with a label of three points on its flag and coat of arms. Due to the city is named after François d'Orléans, Prince of Joinville, son of King Louis-Philippe I of France, who married Princess Francisca of Brazil in 1843.

The fleur-de-lis appears on the coat of Guadeloupe, an overseas département of France in the Caribbean, Saint Barthélemy, an overseas collectivity of France, and French Guiana. The overseas department of Réunion in the Indian Ocean uses the same feature. It appears on the coat of Port Louis, the capital of Mauritius which was named in honour of King Louis XV. On the coat of arms of Saint Lucia it represents the French heritage of the country.

In Ukraine, the Foreign Intelligence Service used the emblem with the coat of arms of Ukraine in conjunction with four golden fleurs-de-lis, along with the motto "Omnia, Vincit, Veritas".

Municipal coats-of-arms

The heraldic fleur-de-lis is still widespread: among the numerous cities which use it as a symbol are some whose names echo the word 'lily', for example, Liljendal, Finland, and Lelystad, Netherlands. This is called canting arms in heraldic terminology. Other European examples of municipal coats-of-arms bearing the fleur-de-lis include Lincoln in England, Morcín in Spain, Wiesbaden and Darmstadt in Germany, Skierniewice in Poland and Jurbarkas in Lithuania. The Swiss municipality of Schlieren and the Estonian municipality of Jõelähtme also have a fleur-de-lis on their coats.

In Malta, the town of Santa Venera has three red fleurs-de-lis on its flag and coat of arms. These are derived from an arch which was part of the Wignacourt Aqueduct that had three sculpted fleurs-de-lis on top, as they were the heraldic symbols of Alof de Wignacourt, the Grand Master who financed its building. Another suburb which developed around the area became known as Fleur-de-Lys, and it also features a red fleur-de-lis on its flag and coat of arms.[54]

Symbolic usage

Some modern usage of the fleur-de-lis reflects "the continuing presence of heraldry in everyday life", often intentionally, but also when users are not aware that they are "prolonging the life of centuries-old insignia and emblems".[55]

Military

Fleurs-de-lis are featured on military badges. E.g., in the United States, the New Jersey Army National Guard unit 112th Field Artillery (Self Propelled)—part of the much larger 42nd Infantry Division Mechanized—which has it in the upper left side of their distinctive unit insignia; the U.S. Army's 2nd Cavalry Regiment, 319th Airborne Field Artillery Regiment, 62nd Medical Brigade, 256th Infantry Brigade Combat Team; and the Corps of Cadets at Louisiana State University. The U.S. Air Force's Special Operations Weather Beret Flash also used a fleurs-de-lis in its design, carried over from its Vietnam War era Commando Weatherman Beret Flash.[56] It is also featured by the Israeli Intelligence Corps, and the First World War Canadian Expeditionary Force. In the British Army, the fleur-de-lis was the cap badge of the Manchester Regiment from 1922 until 1958, and also its successor, the King's Regiment up to its amalgamation in 2006. It commemorates the capture of French regimental colours by their predecessors, the 63rd Regiment of Foot, during the Invasion of Martinique in 1759.[57] It is also the formation sign of the 2nd (Independent) Armored Brigade of the Indian Army, known as the 7th Indian Cavalry Brigade in First World War, which received the emblem for its actions in France.[58]

Sports

The fleur-de-lis is used by a number of sports teams, especially when it echoes a local flag. This is true with the teams from Quebec (Nordiques (ex-NHL), Montreal Expos (ex-MLB) and CF Montréal (MLS)), the teams of New Orleans, Louisiana (Saints (NFL), Pelicans (NBA), and Zephyrs (PCL)), the Serie A team Fiorentina, the Bundesliga side SV Darmstadt 98 (also known as Die Lilien – The Lilies), the Rugby league team Wakefield Trinity Wildcats, the NPSL team Detroit City FC.

Marc-André Fleury, a Canadian ice hockey goaltender, has a fleur-de-lis logo on his mask. The UFC Welterweight Champion from 2006 to 2013, Georges St-Pierre, has a tattoo of the fleur-de-lis on his right calf. The IT University of Copenhagen's soccer team ITU F.C. has it in their logo.[59] France uses the symbol in the official emblem on the 2019 FIFA Women's World Cup.[60]

Education

The emblem appears in coats of arms and logos for universities (like Washington University in St. Louis, Saint Louis University, and University of Louisiana at Lafayette) and schools such as in Hilton College (South Africa), Adamson University and St. Paul's University in the Philippines. The Lady Knights of the University of Arkansas at Monticello have also adopted the fleur de lis as one of the symbols associated with their coat of arms. The flag of Lincolnshire, adopted in 2005, has a fleur-de-lis for the city of Lincoln. It is one of the symbols of the American sororities Kappa Kappa Gamma and Theta Phi Alpha, the American fraternities Alpha Epsilon Pi, Sigma Alpha Epsilon and Sigma Alpha Mu, as well as the international co-ed service fraternity Alpha Phi Omega. It is also used by the high school and college fraternity Scouts Royale Brotherhood of the Philippines.

Scouting

The fleur-de-lis is the main element in the logo of most Scouting organizations. The symbol was first used by Sir Robert Baden-Powell as an arm-badge for soldiers who qualified as scouts (reconnaissance specialists) in the 5th Dragoon Guards, which he commanded at the end of the 19th century; it was later used in cavalry regiments throughout the British Army until 1921. In 1907, Baden-Powell made brass fleur-de-lis badges for the boys attending his first experimental "Boy Scout" camp at Brownsea Island.[61] In his seminal book Scouting for Boys, Baden-Powell referred to the motif as "the arrowhead which shows the North on a map or a compass" and continued; "It is the Badge of the Scout because it points in the right direction and upward... The three points remind you of the three points of the Scout Promise",[62] being duty to God and country, helping others and keeping the Scout Law. The World Scout Emblem of the World Organization of the Scout Movement has elements which are used by most national Scout organizations. The stars stand for truth and knowledge, the encircling rope for unity, and its reef knot or square knot, service.[63]

Organizations

Fleurs-de-lis appear on military insignia and the logos of many organisations. During the 20th century the symbol was adopted by various Scouting organisations worldwide for their badges. Architects and designers use it alone and as a repeated motif in a wide range of contexts, from ironwork to bookbinding, especially where a French context is implied.

Compass rose

The symbol is also often used on a compass rose to mark the north direction, a tradition started by the Portuguese cartographer Jorge de Aguiar in his chart of 1492.

Slave branding

In Mauritius, slaves were branded with a fleur-de-lis, when being punished for escaping or stealing food.[64]

In France, some categories of outlaws were branded with a fleur de lys iron rod as a punishment for crimes involving a banishment sentence. In 1724, the punishment evolved in a system of letters brandings relative to the crime. The fleur de lys became an exclusive punishment for slaves in the colonies.

The fleur-de-lis (or flower de Luce) could be branded on slaves as punishment for certain offenses in French Louisiana. For instance, the Louisiana Code Noir (1724) stated:

XXXII. The runaway slave, who shall continue to be so for one month from the day of his being denounced to the officers of justice, shall have his ears cut off, and shall be branded with the flower de luce on the shoulder: and on a second offence of the same nature, persisted in during one month from the day of his being denounced, he shall be hamstrung, and be marked with the flower de luce on the other shoulder. On the third offence, he shall suffer death".[65]

The Code Noir was an arrangement of controls received in Louisiana in 1724 from other French settlements around the globe, intended to represent the state's slave populace. Those guidelines included marking slaves with the fleur-de-lis as discipline for fleeing.[66]

Other uses

The symbol may be used in less traditional ways. After Hurricane Katrina many New Orleanians of varying ages and backgrounds were tattooed with "one of its cultural emblems" as a "memorial" of the storm, according to a researcher at Tulane University.[67] The US Navy Blue Angels have named a looping flight demonstration manoeuvre after the flower as well, and there are even two surgical procedures called "after the fleur."

American automobile manufacturer Chevrolet takes its name from the racing driver Louis Chevrolet, who was born in Switzerland. But, because the Chevrolet name is French, the manufacturer has used the fleur-de-lis emblems on their cars, most notably the Corvette, but also as a small detail in the badges and emblems on the front of a variety of full-size Chevys from the 1950s, and 1960s. The fleur-de-lis has also been featured more prominently in the emblems of the Caprice sedan.

A fleur-de-lis also appears in some of the logos of local Louisiana media, such as WGNO-TV and WVUE-TV, the local ABC-affiliated and Fox-affiliated television stations in New Orleans respectively.

The fleur-de-lis is one of the objects to drop during the New Year's Eve celebrations in New Orleans, which was broadcast for the first time during Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve '17 with Ryan Seacrest.

New Orleans sludge metal band Crowbar use it as a logo. It's appeared on every album cover since Lifesblood for the Downtrodden and is sometimes incorporated into the artwork (on The Serpent Only Lies as a snake and on Sever the Wicked Hand as a sword's hilt). The Fleur-de-lis is also used decoratively on fire apparatus.

In religion and art

In the Middle Ages, the symbols of lily and fleur-de-lis overlapped considerably in Christian religious art. The historian Michel Pastoureau says that until about 1300 they were found in depictions of Jesus, but gradually they took on Marian symbolism and were associated with the Song of Solomon's "lily among thorns" (lilium inter spinas), understood as a reference to Mary. Other scripture and religious literature in which the lily symbolizes purity and chastity also helped establish the flower as an iconographic attribute of the Virgin. It was also believed that the fleur-de-lis represented the Holy Trinity.[68][69]

In medieval England, from the mid-12th century, a noblewoman's seal often showed the lady with a fleur-de-lis, drawing on the Marian connotations of "female virtue and spirituality".[70] Images of Mary holding the flower first appeared in the 11th century on coins issued by cathedrals dedicated to her, and next on the seals of cathedral chapters, starting with Notre Dame de Paris in 1146. A standard portrayal was of Mary carrying the flower in her right hand, just as she is shown in that church's Virgin of Paris statue (with lily), and in the centre of the stained glass rose window (with fleur-de-lis sceptre) above its main entrance. The flowers may be "simple fleurons, sometimes garden lilies, sometimes genuine heraldic fleurs-de-lis".[21] As attributes of the Madonna, they are often seen in pictures of the Annunciation, notably in those of Sandro Botticelli and Filippo Lippi. Lippi also uses both flowers in other related contexts: for instance, in his Madonna in the Forest.

The three petals of the heraldic design reflect a widespread association with the Holy Trinity, with the band on the bottom symbolizing Mary. The tradition says that without Mary you can not understand the Trinity since it was she who bore the Son.[71] A tradition going back to 14th century France[12] added onto the earlier belief that they also represented faith, wisdom and chivalry. Alternatively, the cord can be seen as representing the one Divine Substance (godhood) of the three Persons, which binds Them together.

"Flower of light" symbolism has sometimes been understood from the archaic variant fleur-de-luce (see Latin lux, luc- = "light"), but the Oxford English Dictionary suggests this arose from the spelling, not from the etymology.[72]

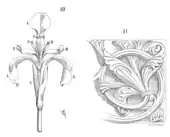

In architecture

In building and architecture, the fleur-de-lis is often placed on top of iron fence posts, as a pointed defence against intruders. It may ornament any tip, point or post with a decorative flourish, for instance, on finials, the arms of a cross, or the point of a gable. The fleur-de-lis can be incorporated in friezes or cornices, although the distinctions between fleur-de-lis, fleuron, and other stylized flowers are not always clear,[8][73] or can be used as a motif in an all-over tiled pattern, perhaps on a floor. It may appear in a building for heraldic reasons, as in some English churches where the design paid a compliment to a local lord who used the flower on his coat of arms. Elsewhere the effect seems purely visual, like the crenellations on the 14th-century Muslim Mosque-Madrassa of Sultan Hassan. It can also be seen on the doors of the 16th-century Hindu Padmanabhaswamy Temple.

In fiction

The symbol has featured in modern fiction on historical and mystical themes, as in the bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code and other books discussing the Priory of Sion. It recurs in French literature, where examples well known in English translation include Fleur-de-Lys de Gondelaurier, a character in The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo, and the mention in Dumas's The Three Musketeers of the old custom of branding a criminal with the sign (fleurdeliser). During the reign of Elizabeth I of England, known as the Elizabethan era, it was a standard name for an iris, a usage which lasted for centuries,[74] but occasionally refers to lilies or other flowers. It also appeared in the novel A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole on a sign composed by the protagonist.

The lilly, Ladie of the flowring field,

The Flowre-deluce, her louely Paramoure— Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene, 1590[75]

In John Steinbeck's East of Eden, Cathy Ames ("Kate") wears a gold watch with a fleur-de-lis pin around her neck.[76]

A variation on the symbol has also been used in the Star Wars franchise to represent the planet of Naboo. The fleur de lis is also used as the heraldic emblem for the Kingdom of Temeria in Andrzej Sapkowski's fantasy novel series The Witcher.

The fleur de lis has also been used in the TV series The Originals, in which it is used to represent the Mikaelson family, the first vampires in the world. The symbol's representation of unity and its usage in New Orleans where the show is set, are used to represent the vow three of the Mikaelson siblings made to each other that they remain together, always and forever.

The fleur de lis is displayed in Champion, a cavalry unit that appears in Heroes of Might and Magic V: Tribes of the East, and is also a symbol adopted by the Sisters of Battle, a faction in Warhammer 40,000. A heavily stylized fleur de lis symbol can also be recognized as the symbol of the ICA in the Hitman series of video games.[77]

The Pokémon villain Lysandre; whose debut game was Pokémon X and Y is known in Japan as フラダリ (Furadari); a romanised name for the fleur-de-lis. Relevant is that Pokémon X and Y are inspired by France.[78][79] Many locations and landmarks across Kalos have real-world inspirations, including Prism Tower (Eiffel Tower), the Lumiose Art Museum (the Louvre) and the stones outside Geosenge Town (Carnac stones).[78][80]

This symbol is also used as the icon for the fictional street gang "Third Street Saints" in the Saints Row series.

See also

- Cross fleury

- Floral emblem

- Armorial of France

- The Golden Lily (disambiguation)

- Iris florentina

- Iris pseudacorus

- Jessant-de-lys

- Lilium

- Palmette

- Prince of Wales's feathers

- Shamrock

- Scottish thistle

- Tree of Life

- Use of the lily in coinage and coat-of-arms in the Land of Israel/Palestine

- Acre, Israel, where the Hospitaller refectory contains two early depictions of the French fleur-de-lis

- Hasmonean coinage, coins minted during Hasmonean rule, sometimes depicting a lily

- Yehud coinage, Achaemenid period coinage often depicting a lily

Explanatory notes

- /ˈflɜːr də ˈliː(s)/; French: [flœʁ də lis]. The Oxford English Dictionary gives both pronunciations for English. In French, Larousse[1] and Robert[2] have the former: [lis]. The CNRTL[3] has that pronunciation for the plant itself, but, following Barbeau-Rodhe 1930, [li] for the compound fleur-de-lis.

References

- Dictionnaire de la Langue Française, Lexis, Paris, 1993

- Petit Robert 1, Paris, 1990

- "LIS : Définition de LIS". www.cnrtl.fr.

- Pastoureau, Michel (1997). Heraldry: Its Origins and Meaning. 'New Horizons' series. Translated by Garvie, Francisca. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 98. ISBN 0-500-30074-7.

- Stefan Buczacki The Herb Bible: The definitive guide to choosing and growing herbs , p. 223, at Google Books

- McVicar, Jekka (2006) [1997]. Jekka's Complete Herb Book (Revised ed.). Bookmark Ltd. ISBN 1845093704.

- Pierre Augustin Boissier de Sauvages (1756). Languedocien Dictionnaire François. p. 154. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- "Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle – Tome 5, Flore – Wikisource" (in French). Fr.wikisource.org. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Velde, François. "The Fleur-de-lis". Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Fleur-de-lis

- Thomas Dudley Fosbroke, A Treatise on the Arts, Manufactures, Manners, and Institutions of the Greek and Romans Volume 2 (1835)

- Michel Pastoureau, Heraldry: its origins and meaning p.99

- "www.anaharsis.ru/histori/Skif/R19.htm - Сервис регистрации доменов и хостинга *.RU-TLD.RU". www.anaharsis.ru. Archived from the original on 28 March 2009.

- Ellen J. Millington, Heraldry in History, Poetry, and Romance, London, 1858, pp. 332-343.

- Lewis, Philippa & Darley, Gillian (1986) Dictionary of Ornament

- Ralph E. Giesey, Models of Rulership in French Royal Ceremonial in Rites of Power: Symbolism, Ritual, and Politics Since the Middle Ages, ed. Wilentz (Princeton 1985), p. 43.

- Michel Pastoureau: Traité d'Héraldique, Paris, 1979

- Claire Richter Sherman (1 January 1995). Imaging Aristotle: Verbal and Visual Representation in Fourteenth-century France. University of California Press. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-0-520-08333-2. OCLC 1008315349.

- Pastoureau, Michel (1997). Heraldry: Its Origins and Meaning. 'New Horizons' series. Translated by Garvie, Francisca. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 99–100. ISBN 9780500300749.

- Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, London, 1909, p. 274.

- Pastoureau, Michel (1997). Heraldry: Its Origins and Meaning. 'New Horizons' series. Translated by Garvie, Francisca. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 100. ISBN 0-500-30074-7.

- Joseph Fr. Michaud; Jean Joseph François Poujoulat (1836). Nouvelle collection des mémoires pour servir a l'histoire de France: depuis le XIIIe siècle jusqu'à la fin du XVIIIe; précédés de notices pour caractériser chaque auteur des mémoires et son époque; suivis de l'analyse des documents historiques qui s'y rapportent. Éditeur du Commentaire analytique du Code civil. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Fox-Davies

- Pierre Goubert (12 April 2002). The Course of French History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-41468-2. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Sir Walter Scott (1833) The Complete Works of Sir Michael Scott, Volume 1 of 7, Canto Fourth, VIII, New York: Conner and Cooke

- Petru Musat Coins image

- Durham, M. E. (2001). Albania and the Albanians : selected articles and letters 1903-1944. Harry Hodgkinson, Bejtullah D. Destani. London: Centre for Albanian Studies. ISBN 1-903616-09-3. OCLC 49270089.

- "Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1992–1998". Flagspot.net. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- "Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1992-1998". Flagspot.net. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- "Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1992-1998". Flagspot.net. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). www.mpr.gov.ba. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - New York State Historical Association (1915). Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association with the Quarterly Journal: 2nd-21st Annual Meeting with a List of New Members. The Association.

It is most probable that the Bourbon Flag was used during the greater part of the occupancy of the French in the region extending southwest from the St. Lawrence to the Mississippi , known as New France... The French flag was probably blue at that time with three golden fleur - de - lis ....

- Wallace, W. Stewart (1948). "Flag of New France". The Encyclopedia of Canada. Vol. II. Toronto: University Associates of Canada. pp. 350–351.

During the French régime in Canada, there does not appear to have been any French national flag in the modern sense of the term. The "Banner of France", which was composed of fleur-de-lys on a blue field, came nearest to being a national flag, since it was carried before the king when he marched to battle, and thus in some sense symbolized the kingdom of France. During the later period of French rule, it would seem that the emblem...was a flag showing the fleur-de-lys on a white ground.... as seen in Florida. There were, however, 68 flags authorized for various services by Louis XIV in 1661; and a number of these were doubtless used in New France

- "Background: The First National Flags". The Canadian Encyclopedia. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

At the time of New France (1534 to the 1760s), two flags could be viewed as having national status. The first was the banner of France — a blue square flag bearing three gold fleurs-de-lys. It was flown above fortifications in the early years of the colony. For instance, it was flown above the lodgings of Pierre Du Gua de Monts at Île Sainte-Croix in 1604. There is some evidence that the banner also flew above Samuel de Champlain’s habitation in 1608. ..... the completely white flag of the French Royal Navy was flown from ships, forts and sometimes at land-claiming ceremonies.

- Lester, Richard A. (1964). "Playing-Card Currency of French Canada". In Edward P. Neufeld (ed.). Money and Banking in Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 9–23. ISBN 9780773560536. OCLC 732600576.

- "INQUINTE.CA | CANADA 150 Years of History ~ The story behind the flag". inquinte.ca.

When Canada was settled as part of France and dubbed "New France," two flags gained national status. One was the Royal Banner of France. This featured a blue background with three gold fleurs-de-lis. A white flag of the French Royal Navy was also flown from ships and forts and sometimes flown at land-claiming ceremonies.

- "Fleur-de-lys | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca.

- "History of the National Flag of Canada". canada.ca. Department of Canadian Heritage. 4 February 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- Heritage, Canadian (28 August 2017). "The history of the National Flag of Canada". aem.

- "Arms & Badges - Royal Arms of Canada, A Brief History". www.heraldry.ca.

- "The Personal Flag of the Queen for use in Canada". Archived from the original on 20 August 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- Georges Duby, France in the Middle Ages 987–1460: From Hugh Capet to Joan of Arc

- Luciano Artusi, Firenze araldica, pp. 280, Polistampa, Firenze, 2006, ISBN 88-596-0149-5

- Hall, James (1974). Dictionary of Subjects & Symbols in Art. Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-433316-7. p.124.

- "Jurbarkas Tourist Information Centre - About region". www.jurbarkotic.lt. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- "Jurbarkas - Herb Jurbarkas (coat of arms, crest)". www.ngw.nl. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Rimša, Edmundas Antanas (1998). Heraldry of Lithuania.

- Moncrieffe, Ian; Pottinger, Don. Simple Heraldry Cheerfully Illustrated. Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd. p. 54.

- Moncrieffe, Ian; Pottinger, Don. Simple Heraldry Cheerfully Illustrated. Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd. p. 20.

- "Carruthers: Our History through our Arms". Archived from the original on 18 August 2017.

- "CLAN CARRUTHERS SOCIETY - Clan History". Archived from the original on 6 November 2019.

- Fleur-de-lis Now Official State Symbol at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 March 2009)

- "2005: The fleur-de-lis becomes a symbol of post-Katrina pride in New Orleans". 31 August 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- "Fleur-de-Lys". Fleur-de-Lys Administrative Committee. 18 November 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- Michel Pastoureau, Heraldry: its origins and meaning p.93-94

- Air Force Weather, Our Heritage 1937 to 2012, prepared by TSgt C. A. Ravenstein (Historical Division, AW3DI, Hq AWS), dated 22 January 2012, last accessed 14 March 2020

- Shepperd, Alan (1973), The King's Regiment, Osprey Publishing Ltd, ISBN 0-85045-120-5 (p. 39)

- "Bharat Rakshak :: Land Forces Site – Armoured Formations". Archived from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- "ITU FC". www.facebook.com.

- "Picture". img.washingtonpost.com/. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Walker, Colin (March 2007). "The Evolution of The World Badge". Scouting Milestones. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- Baden-Powell, Robert Scouting for Boys, Arthur Pearson, (Campfire Yarn No. 3 – Becoming a Scout)

- Troop 25. "Origin of the World Scouting Symbol "Fleur-de-lis"". Web. USA: Troop 25, Scouting of America. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- Bernardin de Saint-PierreJourney to Mauritius, p. 15, at Google Books

- BlackPast (28 July 2007). "(1724) Louisiana's Code Noir is italicized". Blackpast.org. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "The Fleur-de-lis". Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "New Orleans LA Living & Lifestyle". NOLA.com. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- "The Fleur-de-Lys". Heraldica.org. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Post, W. Ellwood (1986). Saints, Signs, and Symbols. Wilton, Connecticut: Morehouse-Barlow. p. 29.

- Susan M. Johns, Noblewomen, Aristocracy and Power in the Twelfth-Century Anglo-Norman Realm (Manchester 2003) p130

- F. R. Webber; Ralph Adams Cram (October 2013). Church Symbolism. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-4941-0856-4.

- A "fanciful derivation", Oxford English Dictionary (1989)

- Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle – Tome 5, Flore

- OED

- "The Faerie Queene: Book II". Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- See the beginning of Chapter 40.

- "Hitman logo and symbol, meaning, history, PNG".

- Campbell, Colin (5 July 2013). "How France inspired Junichi Masuda in making Pokémon X and Y". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Watts, Steve (23 October 2013). "How Europe inspired Pokemon X and Y's creature designs". Shacknews. GameFly. Archived from the original on 19 July 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- O'Farrell, Brad (10 April 2015). "How Pokemon's world was shaped by real-world locations". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

External links

- The Fleur-de-Lys at Heraldica.org

- The Origin of the Fleur-de-Lis

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.png.webp)