Economies of scale

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of output produced per unit of time. A decrease in cost per unit of output enables an increase in scale. At the basis of economies of scale, there may be technical, statistical, organizational or related factors to the degree of market control. This is just a partial description of the concept.

Economies of scale apply to a variety of the organizational and business situations and at various levels, such as a production, plant or an entire enterprise. When average costs start falling as output increases, then economies of scale occur. Some economies of scale, such as capital cost of manufacturing facilities and friction loss of transportation and industrial equipment, have a physical or engineering basis.

The economic concept dates back to Adam Smith and the idea of obtaining larger production returns through the use of division of labor.[1] Diseconomies of scale are the opposite.

Economies of scale often have limits, such as passing the optimum design point where costs per additional unit begin to increase. Common limits include exceeding the nearby raw material supply, such as wood in the lumber, pulp and paper industry. A common limit for a low cost per unit weight commodities is saturating the regional market, thus having to ship product uneconomic distances. Other limits include using energy less efficiently or having a higher defect rate.

Large producers are usually efficient at long runs of a product grade (a commodity) and find it costly to switch grades frequently. They will, therefore, avoid specialty grades even though they have higher margins. Often smaller (usually older) manufacturing facilities remain viable by changing from commodity-grade production to specialty products.[lower-alpha 1][2]

Economies of scale must be distinguished from economies stemming from an increase in the production of a given plant. When a plant is used below its optimal production capacity, increases in its degree of utilization bring about decreases in the total average cost of production. As noticed, among the others, by Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1966) and Nicholas Kaldor (1972) these economies are not economies of scale.

Overview

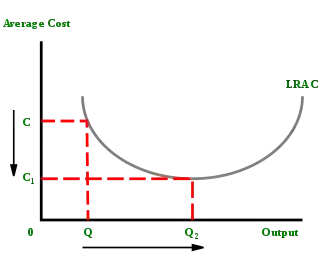

The simple meaning of economies of scale is doing things more efficiently with increasing size.[3] Common sources of economies of scale are purchasing (bulk buying of materials through long-term contracts), managerial (increasing the specialization of managers), financial (obtaining lower-interest charges when borrowing from banks and having access to a greater range of financial instruments), marketing (spreading the cost of advertising over a greater range of output in media markets), and technological (taking advantage of returns to scale in the production function). Each of these factors reduces the long run average costs (LRAC) of production by shifting the short-run average total cost (SRATC) curve down and to the right.

Economies of scale is a concept that may explain patterns in international trade or in the number of firms in a given market. The exploitation of economies of scale helps explain why companies grow large in some industries. It is also a justification for free trade policies, since some economies of scale may require a larger market than is possible within a particular country—for example, it would not be efficient for Liechtenstein to have its own carmaker if they only sold to their local market. A lone carmaker may be profitable, but even more so if they exported cars to global markets in addition to selling to the local market. Economies of scale also play a role in a "natural monopoly". There is a distinction between two types of economies of scale: internal and external. An industry that exhibits an internal economy of scale is one where the costs of production fall when the number of firms in the industry drops, but the remaining firms increase their production to match previous levels. Conversely, an industry exhibits an external economy of scale when costs drop due to the introduction of more firms, thus allowing for more efficient use of specialized services and machinery.

Determinants of economies of scale

Physical and engineering basis: economies of increased dimension

Some of the economies of scale recognized in engineering have a physical basis, such as the square–cube law, by which the surface of a vessel increases by the square of the dimensions while the volume increases by the cube. This law has a direct effect on the capital cost of such things as buildings, factories, pipelines, ships and airplanes.[lower-alpha 2]

In structural engineering, the strength of beams increases with the cube of the thickness.

Drag loss of vehicles like aircraft or ships generally increases less than proportional with increasing cargo volume, although the physical details can be quite complicated. Therefore, making them larger usually results in less fuel consumption per ton of cargo at a given speed.

Heat loss from industrial processes vary per unit of volume for pipes, tanks and other vessels in a relationship somewhat similar to the square–cube law.[lower-alpha 3][4] In some productions, an increase in the size of the plant reduces the average variable cost, thanks to the energy savings resulting from the lower dispersion of heat.

Economies of increased dimension are often misinterpreted because of the confusion between indivisibility and three-dimensionality of space. This confusion arises from the fact that three-dimensional production elements, such as pipes and ovens, once installed and operating, are always technically indivisible. However, the economies of scale due to the increase in size do not depend on indivisibility but exclusively on the three-dimensionality of space. Indeed, indivisibility only entails the existence of economies of scale produced by the balancing of productive capacities, considered above; or of increasing returns in the utilisation of a single plant, due to its more efficient use as the quantity produced increases. However, this latter phenomenon has nothing to do with the economies of scale which, by definition, are linked to the use of a larger plant.[5]

Economies in holding stocks and reserves

At the base of economies of scale there are also returns to scale linked to statistical factors. In fact, the greater of the number of resources involved, the smaller, in proportion, is the quantity of reserves necessary to cope with unforeseen contingencies (for instance, machine spare parts, inventories, circulating capital, etc.).[6]

Transaction economies

A larger scale generally determines greater bargaining power over input prices and therefore benefits from pecuniary economies in terms of purchasing raw materials and intermediate goods compared to companies that make orders for smaller amounts. In this case, we speak of pecuniary economies, to highlight the fact that nothing changes from the "physical" point of view of the returns to scale. Furthermore, supply contracts entail fixed costs which lead to decreasing average costs if the scale of production increases.[7] This is of important utility in the study of corporate finance.[8]

Economies deriving from the balancing of production capacity

Economies of productive capacity balancing derives from the possibility that a larger scale of production involves a more efficient use of the production capacities of the individual phases of the production process. If the inputs are indivisible and complementary, a small scale may be subject to idle times or to the underutilization of the productive capacity of some sub-processes. A higher production scale can make the different production capacities compatible. The reduction in machinery idle times is crucial in the case of a high cost of machinery.[9]

Economies resulting from the division of labour and the use of superior techniques

A larger scale allows for a more efficient division of labour. The economies of division of labour derive from the increase in production speed, from the possibility of using specialized personnel and adopting more efficient techniques. An increase in the division of labour inevitably leads to changes in the quality of inputs and outputs.[10]

Managerial economics

Many administrative and organizational activities are mostly cognitive and, therefore, largely independent of the scale of production.[11] When the size of the company and the division of labour increase, there are a number of advantages due to the possibility of making organizational management more effective and perfecting accounting and control techniques.[12] Furthermore, the procedures and routines that turned out to be the best can be reproduced by managers at different times and places.

Learning and growth economies

Learning and growth economies are at the base of dynamic economies of scale, associated with the process of growth of the scale dimension and not to the dimension of scale per se. Learning by doing implies improvements in the ability to perform and promotes the introduction of incremental innovations with a progressive lowering of average costs.[13] Learning economies are directly proportional to the cumulative production (experience curve). Growth economies occur when a company acquires an advantage by increasing its size. These economies are due to the presence of some resource or competence that is not fully utilized, or to the existence of specific market positions that create a differential advantage in expanding the size of the firms. That growth economies disappear once the scale size expansion process is completed. For example, a company that owns a supermarket chain benefits from an economy of growth if, opening a new supermarket, it gets an increase in the price of the land it owns around the new supermarket. The sale of these lands to economic operators, who wish to open shops near the supermarket, allows the company in question to make a profit, making a profit on the revaluation of the value of building land.[14]

Capital and operating cost

Overall costs of capital projects are known to be subject to economies of scale. A crude estimate is that if the capital cost for a given sized piece of equipment is known, changing the size will change the capital cost by the 0.6 power of the capacity ratio (the point six to the power rule).[15][lower-alpha 4]

In estimating capital cost, it typically requires an insignificant amount of labor, and possibly not much more in materials, to install a larger capacity electrical wire or pipe having significantly greater capacity.[16]

The cost of a unit of capacity of many types of equipment, such as electric motors, centrifugal pumps, diesel and gasoline engines, decreases as size increases. Also, the efficiency increases with size.[17]

Crew size and other operating costs for ships, trains and airplanes

Operating crew size for ships, airplanes, trains, etc., does not increase in direct proportion to capacity.[18] (Operating crew consists of pilots, co-pilots, navigators, etc. and does not include passenger service personnel.) Many aircraft models were significantly lengthened or "stretched" to increase payload.[19]

Many manufacturing facilities, especially those making bulk materials like chemicals, refined petroleum products, cement and paper, have labor requirements that are not greatly influenced by changes in plant capacity. This is because labor requirements of automated processes tend to be based on the complexity of the operation rather than production rate, and many manufacturing facilities have nearly the same basic number of processing steps and pieces of equipment, regardless of production capacity.

Economical use of byproducts

Karl Marx noted that large scale manufacturing allowed economical use of products that would otherwise be waste.[20] Marx cited the chemical industry as an example, which today along with petrochemicals, remains highly dependent on turning various residual reactant streams into salable products. In the pulp and paper industry, it is economical to burn bark and fine wood particles to produce process steam and to recover the spent pulping chemicals for conversion back to a usable form.

Economies of scale and the size of exporter

Large and more productive firms typically generate enough net revenues abroad to cover the fixed costs associated with exporting.[21] However, in the event of trade liberalization, resources will have to be reallocated toward the more productive firm, which raises the average productivity within the industry.[22]

Firms differ in their labor productivity and the quality of their goods produced. It is because of this that more efficient firms are more likely to generate more net income abroad and thus become exporters of their goods or services. There is a correlating relationship between a firms' total sales and underlying efficiency. Firms with higher productivity will always outperform a firm with lower productivity which will lead to lower sales. Through trade liberalization, organizations are able to drop their trade costs due to export growth. However, trade liberalization does not account for any tariff reduction or shipping logistics improvement.[22] However, total economies of scale is based on the exporters individual frequency and size. So large-scale companies are more likely to have a lower cost per unit as opposed to small-scale companies. Likewise, high trade frequency companies are able to reduce their overall cost attributed per unit when compared to those of low-trade frequency companies. [23]

Economies of scale and returns to scale

Economies of scale is related to and can easily be confused with the theoretical economic notion of returns to scale. Where economies of scale refer to a firm's costs, returns to scale describe the relationship between inputs and outputs in a long-run (all inputs variable) production function. A production function has constant returns to scale if increasing all inputs by some proportion results in output increasing by that same proportion. Returns are decreasing if, say, doubling inputs results in less than double the output, and increasing if more than double the output. If a mathematical function is used to represent the production function, and if that production function is homogeneous, returns to scale are represented by the degree of homogeneity of the function. Homogeneous production functions with constant returns to scale are first degree homogeneous, increasing returns to scale are represented by degrees of homogeneity greater than one, and decreasing returns to scale by degrees of homogeneity less than one.

If the firm is a perfect competitor in all input markets, and thus the per-unit prices of all its inputs are unaffected by how much of the inputs the firm purchases, then it can be shown that at a particular level of output, the firm has economies of scale if and only if it has increasing returns to scale, has diseconomies of scale if and only if it has decreasing returns to scale, and has neither economies nor diseconomies of scale if it has constant returns to scale.[24][25][26] In this case, with perfect competition in the output market the long-run equilibrium will involve all firms operating at the minimum point of their long-run average cost curves (i.e., at the borderline between economies and diseconomies of scale).

If, however, the firm is not a perfect competitor in the input markets, then the above conclusions are modified. For example, if there are increasing returns to scale in some range of output levels, but the firm is so big in one or more input markets that increasing its purchases of an input drives up the input's per-unit cost, then the firm could have diseconomies of scale in that range of output levels. Conversely, if the firm is able to get bulk discounts of an input, then it could have economies of scale in some range of output levels even if it has decreasing returns in production in that output range.

In essence, returns to scale refer to the variation in the relationship between inputs and output. This relationship is therefore expressed in "physical" terms. But when talking about economies of scale, the relation taken into consideration is that between the average production cost and the dimension of scale. Economies of scale therefore are affected by variations in input prices. If input prices remain the same as their quantities purchased by the firm increase, the notions of increasing returns to scale and economies of scale can be considered equivalent. However, if input prices vary in relation to their quantities purchased by the company, it is necessary to distinguish between returns to scale and economies of scale. The concept of economies of scale is more general than that of returns to scale since it includes the possibility of changes in the price of inputs when the quantity purchased of inputs varies with changes in the scale of production.[27]

The literature assumed that due to the competitive nature of reverse auctions, and in order to compensate for lower prices and lower margins, suppliers seek higher volumes to maintain or increase the total revenue. Buyers, in turn, benefit from the lower transaction costs and economies of scale that result from larger volumes. In part as a result, numerous studies have indicated that the procurement volume must be sufficiently high to provide sufficient profits to attract enough suppliers, and provide buyers with enough savings to cover their additional costs.[28]

However, surprisingly enough, Shalev and Asbjornse found, in their research based on 139 reverse auctions conducted in the public sector by public sector buyers, that the higher auction volume, or economies of scale, did not lead to better success of the auction. They found that auction volume did not correlate with competition, nor with the number of bidders, suggesting that auction volume does not promote additional competition. They noted, however, that their data included a wide range of products, and the degree of competition in each market varied significantly, and offer that further research on this issue should be conducted to determine whether these findings remain the same when purchasing the same product for both small and high volumes. Keeping competitive factors constant, increasing auction volume may further increase competition.[28]

Economies of scale in the history of economic analysis

Economies of scale in classical economists

The first systematic analysis of the advantages of the division of labour capable of generating economies of scale, both in a static and dynamic sense, was that contained in the famous First Book of Wealth of Nations (1776) by Adam Smith, generally considered the founder of political economy as an autonomous discipline.

John Stuart Mill, in Chapter IX of the First Book of his Principles, referring to the work of Charles Babbage (On the economics of machines and manufactories), widely analyses the relationships between increasing returns and scale of production all inside the production unit.

Economies of scale in Marx and distributional consequences

In Das Kapital (1867), Karl Marx, referring to Charles Babbage, extensively analyzed economies of scale and concludes that they are one of the factors underlying the ever-increasing concentration of capital. Marx observes that in the capitalist system the technical conditions of the work process are continuously revolutionized in order to increase the surplus by improving the productive force of work. According to Marx, with the cooperation of many workers brings about an economy in the use of the means of production and an increase in productivity due to the increase in the division of labour. Furthermore, the increase in the size of the machinery allows significant savings in construction, installation and operation costs. The tendency to exploit economies of scale entails a continuous increase in the volume of production which, in turn, requires a constant expansion of the size of the market.[29] However, if the market does not expand at the same rate as production increases, overproduction crises can occur. According to Marx the capitalist system is therefore characterized by two tendencies, connected to economies of scale: towards a growing concentration and towards economic crises due to overproduction.[30]

In his 1844 Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, Karl Marx observes that economies of scale have historically been associated with an increasing concentration of private wealth and have been used to justify such concentration. Marx points out that concentrated private ownership of large-scale economic enterprises is a historically contingent fact, and not essential to the nature of such enterprises. In the case of agriculture, for example, Marx calls attention to the sophistical nature of the arguments used to justify the system of concentrated ownership of land:

- As for large landed property, its defenders have always sophistically identified the economic advantages offered by large-scale agriculture with large-scale landed property, as if it were not precisely as a result of the abolition of property that this advantage, for one thing, received its greatest possible extension, and, for another, only then would be of social benefit.[31]

Instead of concentrated private ownership of land, Marx recommends that economies of scale should instead be realized by associations:

- Association, applied to land, shares the economic advantage of large-scale landed property, and first brings to realization the original tendency inherent in land-division, namely, equality. In the same way association re-establishes, now on a rational basis, no longer mediated by serfdom, overlordship and the silly mysticism of property, the intimate ties of man with the earth, for the earth ceases to be an object of huckstering, and through free labor and free enjoyment becomes once more a true personal property of man.[31]

Economies of scale in Marshall

Alfred Marshall notes that "some, among whom Cournot himself," have considered "the internal economies [...] apparently without noticing that their premises lead inevitably to the conclusion that, whatever firm first gets a good start will obtain a monopoly of the whole business of its trade … ".[32] Marshall believes that there are factors that limit this trend toward monopoly, and in particular:

- the death of the founder of the firm and the difficulty that the successors may have inherited his/her entrepreneurial skills;

- the difficulty of reaching new markets for one's goods;

- the growing difficulty of being able to adapt to changes in demand and to new techniques of production;

- The effects of external economies, that is the particular type of economies of scale connected not to the production scale of an individual production unit, but to that of an entire sector.[33]

Sraffa's critique

Piero Sraffa observes that Marshall, in order to justify the operation of the law of increasing returns without it coming into conflict with the hypothesis of free competition, tended to highlight the advantages of external economies linked to an increase in the production of an entire sector of activity. However, "those economies which are external from the point of view of the individual firm, but internal as regards the industry in its aggregate, constitute precisely the class which is most seldom to be met with." "In any case - Sraffa notes – in so far as external economies of the kind in question exist, they are not linked to be called forth by small increases in production," as required by the marginalist theory of price.[34] Sraffa points out that, in the equilibrium theory of the individual industries, the presence of external economies cannot play an important role because this theory is based on marginal changes in the quantities produced.

Sraffa concludes that, if the hypothesis of perfect competition is maintained, economies of scale should be excluded. He then suggests the possibility of abandoning the assumption of free competition to address the study of firms that have their own particular market.[35] This stimulated a whole series of studies on the cases of imperfect competition in Cambridge. However, in the succeeding years Sraffa followed a different path of research that brought him to write and publish his main work Production of commodities by means of commodities (Sraffa 1966). In this book, Sraffa determines relative prices assuming no changes in output, so that no question arises as to the variation or constancy of returns.

Economies of scale and the tendency towards monopoly: "Cournot's dilemma"

It has been noted that in many industrial sectors there are numerous companies with different sizes and organizational structures, despite the presence of significant economies of scale. This contradiction, between the empirical evidence and the logical incompatibility between economies of scale and competition, has been called the ‘Cournot dilemma’.[36] As Mario Morroni observes, Cournot's dilemma appears to be unsolvable if we only consider the effects of economies of scale on the dimension of scale.[37] If, on the other hand, the analysis is expanded, including the aspects concerning the development of knowledge and the organization of transactions, it is possible to conclude that economies of scale do not always lead to monopoly. In fact, the competitive advantages deriving from the development of the firm's capabilities and from the management of transactions with suppliers and customers can counterbalance those provided by the scale, thus counteracting the tendency towards a monopoly inherent in economies of scale. In other words, the heterogeneity of the organizational forms and of the size of the companies operating in a sector of activity can be determined by factors regarding the quality of the products, the production flexibility, the contractual methods, the learning opportunities, the heterogeneity of preferences of customers who express a differentiated demand with respect to the quality of the product, and assistance before and after the sale. Very different organizational forms can therefore co-exist in the same sector of activity, even in the presence of economies of scale, such as, for example, flexible production on a large scale, small-scale flexible production, mass production, industrial production based on rigid technologies associated with flexible organizational systems and traditional artisan production. The considerations regarding economies of scale are therefore important, but not sufficient to explain the size of the company and the market structure. It is also necessary to take into account the factors linked to the development of capabilities and the management of transaction costs.[37]

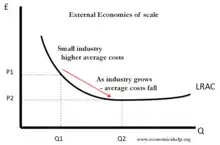

External economies of scale

External economies of scale tend to be more prevalent than internal economies of scale.[38] Through the external economies of scale, the entry of new firms benefits all existing competitors as it creates greater competition and also reduces the average cost for all firms as opposed to internal economies of scale which only allows benefits to the individual firm.[39] Advantages that arise from external economies of scale include;

- Expansion of the industry.

- Benefits most or all of the firms within the industry.

- Can lead to rapid growth of local governments.

Sources

Purchasing

Firms are able to lower their average costs by buying their inputs required for the production process in bulk or from special wholesalers.[40]

Managerial

Firms might be able to lower their average costs by improving their management structure within the firm. This can range from hiring better skilled or more experienced managers from the industry.[40]

Technological

Technological advancements will change the production process which will subsequently reduce the overall cost per unit.[41]

See also

- Economies of density

- Economies of scope

- Ideal firm size

- Mass production

- Network effect

Notes

- Manufacture of specialty grades by small scale producers is a common practice in steel, paper, and many commodity industries today. See various industry trade publications.

- See various estimating guides, such as Means. Also see various engineering economics texts related to plant design and construction, etc.

- The relationship is rather complex. See engineering texts on heat transfer.

- In practice, capital cost estimates are prepared from specifications, budget grade vendor pricing for equipment, general arrangement drawings and materials take-offs from the drawings. This information is then used in cost formulas to arrive at a final detailed estimate.

References

Citations

- O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 157. ISBN 978-0-13-063085-8.

- Landes, David. S. (1969). The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present. Cambridge, New York: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-09418-4. Landes describes the problem of new steel mills in late 19th century Britain being too large for the market and unable to economically produce short production runs of specialty grades. The old mills had another advantage in that they were fully amortized.

- Chandler, Alfred D. Jr. (1993). The Visible Hand: The Management Revolution in American Business. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0674940529. Chandler uses the example of high turn over in distribution.

- Robinson (1958), pp. 22–23; Scherer (1980), pp. 82–83; Pratten (1991), pp. 16–17.

- Morroni (2006), pp. 169–170.

- Baumol (1961), p. 1.

- Morroni (2006), pp. 170–171.

- "Economies of Scale - Definition, Types, Effects of Economies of Scale". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- Morroni (2006), p. 166.

- Smith (1976); Pratten (1991), pp. 7, 17–8 On the relationship between built-in technical change and scale growth, see Evangelista (1999), chapter 4.

- Demsetz (1995), pp. 11, 31–32 shows how these economies of scale in the acquisition of specialized knowledge play an essential role in the existence of the company.

- Scherer (1980), p. 86; Penrose (1959), pp. 92 ff.; Demsetz (1995), pp. 31–2.

- Rosenberg (1982); Levin et al. (1987); Scherer (2000), p. 22.

- Penrose (1959), pp. 99–101; Morroni (2006), p. 172.

- [[In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to size, output, or scale of operation, with cost per unit of output generally decreasing with increasing scale as fixed costs are spread out over more units of output. Often operational efficiency is also greater with increasing scale, leading to lower variable cost as well. Economies of scale apply to a variety of organizational and business situations and at various levels, such as a business or manufacturing unit, plant or an entire enterprise. For example, a large manufacturing facility would be expected to have a lower cost per unit of output than a smaller facility, all other factors being equal, while a company with many facilities should have a cost advantage over a competitor with fewer. Some economies|Moore, Fredrick T.]] (May 1959). "Economies of Scale: Some Statistical Evidence" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 73 (2): 232–245. doi:10.2307/1883722. JSTOR 1883722.

- See various estimating guides that publish tables of tasks commonly encountered in building trades with estimates of labor hours and costs per hour for the trade, often with regional pricing.

- See various engineering handbooks and manufacturers data.

- Rosenberg 1982, p. 63<Specifically mentions ships.>

- Rosenberg (1982), pp. 127–128.

- Rosenberg (1982).

- Melitz, Marc J (2003). "The Impact of Trade on Intra-industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity" (PDF). Econometrica. 71 (6): 1695–1725. doi:10.1111/1468-0262.00467. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Armenter, Roc; Koren, Miklós (2015). "Economies of Scale and the Size of Exporters". Journal of the European Economic Association. 13 (1): 482–511. doi:10.1111/jeea.12108. SSRN 1448001. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- Baumgartner, Kerstin; Fuetterer, André; Thoneman, Ulrich W (2012). "Supply chain design considering economies of scale and transport frequencies". European Journal of Operational Research. 218 (3): 789–800. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2011.11.032.

- Gelles, Gregory M.; Mitchell, Douglas W. (1996). "Returns to Scale and Economies of Scale: Further Observations". Journal of Economic Education. 27 (3): 259–261. doi:10.1080/00220485.1996.10844915. JSTOR 1183297.

- Frisch, R. (1965). Theory of Production. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

- Ferguson, C. E. (1969). The Neoclassical Theory of Production & Distribution. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-07453-7.

- Morroni (1992), p. 142; Morroni (2006), pp. 164–165.

- Shalev, Moshe Eitan; Asbjornsen, Stee (2010). "Electronic Reverse Auctions and the Public Sector – Factors of Success". Journal of Public Procurement. 10 (3): 428–452. SSRN 1727409.

- Marx (1867), pp. 432–442, 469.

- Marx (1894), pp. 172, 288, 360–365.

- Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, M. Milligan, trans. (1988), p. 65–66

- Marshall (1890), 380, note 1; cf. Cournot (1838), pp. 96 ff.

- Marshall (1890), pp. 232–238, 378–380.

- Sraffa (1926), p. 49; Sraffa (1925).

- Sraffa (1926), p. 58.

- Arrow (1979), p. 156.

- Morroni (2006), pp. 253–256.

- Broadberry, Stephen; Marrison, Andrew (2002). "External economies of scale in the Lancashire cotton industry, 1900–1950". The Economic History Review. 55 (1): 51–77. doi:10.1111/1468-0289.00214. JSTOR 3091815. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Mukherjee, Arijit (2010). "External Economies of Scale and Insufficient Entry". Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade. 10 (3): 365-371. doi:10.1007/s10842-010-0069-y. S2CID 153725116. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Xue, Xiao; Wang, Shufang; Lu, Baoyun (2015). "Computational Experiment Approach to Controlled Evolution of Procurement Pattern in Cluster Supply Chain". Sustainability. 7 (1): 1516–1541. doi:10.3390/su7021516.

- Rajagopal (2014). Innovations, Technology, and Economies of Scale (1 ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 174–199. ISBN 978-1-137-36678-8.

General and cited references

- Arrow, Kenneth (1979). "The division of labor in the economy, the polity, and society". In O’Driscoll, Gerald P. Jr (ed.). Adam Smith and Modern Political Economy. Bicentennial Essays on the Wealth of Nations. Uckfield: The Iowa State University Press. pp. 153–164. ISBN 978-0813819006.

- Babbage, Charles (1832). On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures. London: Knight.

- Baumol, William Jack (1961). Economic Theory and Operational Analysis (4 ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780132271240.

- Cournot, Antoine Augustin (1838). Recherches sur les Principes Mathématiques de la Théorie des Richesses (in French). Paris: Hachette. ISBN 978-2012871786. New ed. with Appendices by Léon Walras, Joseph Bertrand and Vilfredo Pareto, Introduction and notes by Georges Lutfalla, Paris: Librairie des Sciences Politiques et Sociales Marcel Rivière, 1938. English translation: Cournot, Antoine Augustin (1927). Researches into the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth. Translated by Bacon, Nathaniel T. New York: Macmillan. Repr. New York: A.M. Kelley, 1971.

- Demsetz, Harold (1995). The Economics of the Business Firm. Seven Critical Comments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521588650. Repr. 1997.

- Evangelista, Rinaldo (1999). Knowledge and Investment. The Source of Innovation in Industry. cheltenham: Elgar.

- Färe, Rolf; Grosskopf, Shawna; Lovell, C. A. Knox (June 1986). "Scale Economies and Duality". Journal of Economics. 46 (2): 175–182. doi:10.1007/BF01229228. S2CID 154480027.

- Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1966). Analytical Economics: Issues and Problems. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674281639.

- Hanoch, Giora (June 1975). "The Elasticity of Scale and the Shape of Average Costs". American Economic Review. 65 (3): 492–497. JSTOR 1804855.

- Kaldor, Nicholas (December 1972). "The irrelevance of equilibrium economics". The Economic Journal. 82 (328): 1237–1255. doi:10.2307/2231304. JSTOR 2231304.

- Levin, Richard C.; Klevorick, Alvin K.; Nelson, Richard R.; Winter, Sidney G. (1987). Baily, M.N.; Winston, C. (eds.). "Appropriating the returns from industrial research and development" (PDF). Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1987 (3): 783–820. doi:10.2307/2534454. JSTOR 2534454. S2CID 51821102.

- Marshall, Alfred (1890). Principles of Economics (8 ed.). London: Macmillan. Repr. 1990.

- Marx, Karl (1867). Das Kapital [Capital. A Critique to Political Economy]. Vol. 1. Translated by Fowkes, Ben. London: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review. Repr. 1990.

- Marx, Karl (1894). Das Kapital [Capital. A Critique to Political Economy]. Vol. 3. Translated by Fernbach, David B.; introduced by Mandel, Ernest. London: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review.

- Morroni, Mario (1992). Production Process and Technical Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511599019.

- Morroni, Mario (2006). Knowledge, Scale and Transactions in the Theory of the Firm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107321007. Repr. 2009.

- Panzar, John; Willig, Robert D. (August 1977). "Economies of Scale in Multi-Output Production". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 91 (3): 481–493. doi:10.2307/1885979. JSTOR 1885979.

- Penrose, Edith (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm (3 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198289777. Repr. (1997).

- Pratten, Clifford Frederick (1991). The Competitiveness of Small Firms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Robinson, Austin (1958) [1931]. The Structure of Competitive Industry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rosenberg, Nathan (1982). "Learning by using". Inside the Black Box. Technology and Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Scherer, F.M. (1980). Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance (2 ed.). Chicago: Rand McNally. ISBN 9780528671029.

- Scherer, F.M. (2000). "Professor Sutton's 'Technology and market structure'". The Journal of Industrial Economics. 48 (2): 215–223. doi:10.1111/1467-6451.00120.

- Silvestre, Joaquim (1987). "Economies and Diseconomies of Scale". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. Vol. 2. London: Macmillan. pp. 80–84. ISBN 978-0-333-37235-7.

- Smith, Adam (1976) [1776]. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sraffa, Piero (1925). "Sulle relazioni tra costo e quantità prodotta". Annali di Economia (in Italian). 2: 277–328. English translation: Sraffa, Piero (1998). "On the relations between cost and quantity produced". Italian Economic Papers. Volume III. Translated by Pasinetti, L.L. (1998 ed.). Bologna: Società Italiana degli Economisti, Oxford University Press, Il Mulino. ISBN 978-0198290346. Repr. in Kurz, H.D.; Salvadori, N. (2003). The Legacy of Piero Sraffa. Vol. 2 (2003 ed.). Cheltenham: An Elgar Reference Collection. pp. 3–43. ISBN 978-1-84064-439-5.

- Sraffa, Piero (December 1926). "The law of returns under competitive conditions". The Economic Journal. 36 (144): 535–550. doi:10.2307/2959866. JSTOR 2959866. S2CID 6458099. Repr. in Kurz, H.D.; Salvadori, N. (2003). The Legacy of Piero Sraffa. Vol. 2 (2003 ed.). Cheltenham: An Elgar Reference Collection. pp. 44–59. ISBN 978-1-84064-439-5.

- Sraffa, Piero (1966). Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities. Prelude to a Critique of Economic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521099691.

- Zelenyuk, V. (2013). "A scale elasticity measure for directional distance function and its dual: Theory and DEA estimation". European Journal of Operational Research. 228 (3): 592–600. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2013.01.012.

- Zelenyuk, V. (2014). "Scale efficiency and homotheticity: equivalence of primal and dual measures". Journal of Productivity Analysis. 42 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1007/s11123-013-0361-z. S2CID 122978026.

External links

- Economies of Scale Definition by The Linux Information Project (LINFO)

- Economies of Scale by Economics Online