Eurostar

Eurostar is an international high-speed rail service connecting the United Kingdom with France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Most Eurostar trains travel through the Channel Tunnel between the United Kingdom and France, owned and operated separately by Getlink.

.JPG.webp) | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Franchise(s) | Not subject to franchising; international joint operation 1994–2009; international high speed operator 2010–present | ||

| Main stations(s) |

| ||

| Fleet size |

| ||

| Stations called at | 14 | ||

| Parent company | Eurostar International Limited | ||

| Reporting mark | ES | ||

| Other | |||

| Website | www | ||

| |||

The London terminus is London St Pancras International; the other British calling points are Ebbsfleet International and Ashford International in Kent. Intermediate calling points in France are Calais-Fréthun and Lille-Europe. Trains to Paris terminate at Gare du Nord. Trains to Belgium and the Netherlands serve Brussels-South and Rotterdam Centraal, before terminating at Amsterdam Centraal. Additionally, in France there are direct services from London to Marne-la-Vallée–Chessy (Disneyland Paris) until June 2023 and seasonal direct services to the French Alps in winter.

The service is operated by 11 Class 373/1 trainsets, each with 18 coaches, and 17 Class 374 trainsets, each with 16 coaches. The trains run at up to 320 kilometres per hour (200 mph) on high-speed lines. The LGV Nord high-speed line in France opened before Eurostar services began in 1994, and newer lines enabling faster journeys were added later: HSL 1 in Belgium and High Speed 1 in south-east England. The French and Belgian parts of the network are shared with Paris–Brussels Thalys services and TGV trains.

Eurostar is operated by Eurostar International Limited (EIL), which is owned by Eurostar Group.

In December 2021, Eurostar said it intended to move its administrative activities from London to Brussels as part of a forthcoming merger with Thalys which was approved in March 2022, citing problems with doing business in the UK and stating that being based in an EU country would make expansion and development easier.

History

Conception and planning

.svg.png.webp)

The history of Eurostar can be traced to the choice in 1986 of a rail tunnel to provide a cross-channel link between Britain and France.[1] A previous attempt to construct a tunnel between the two nations had begun in 1974, but was quickly aborted. Construction began afresh in 1988. Eurotunnel was created to manage and own the tunnel, which was finished in 1993, the official opening taking place on 6 May 1994.[2]

In addition to the tunnel's shuttle trains carrying cars and lorries between Folkestone and Calais, the tunnel opened up the possibility of through passenger and freight train services between places further afield.[3] British Rail and SNCF contracted with Eurotunnel to use half the tunnel's capacity for this purpose. In 1987, Britain, France and Belgium set up an International Project Group to specify a train to provide an international high-speed passenger service through the tunnel. France had been operating high-speed TGV services since 1981, and had begun construction of a new high-speed line between Paris and the Channel Tunnel, LGV Nord; French TGV technology was chosen as the basis for the new trains. An order for 30 trainsets, to be manufactured in France but with some British and Belgian components, was placed in December 1989. On 20 June 1993, the first Eurostar test train travelled through the tunnel to the UK.[4] Various technical difficulties in running the new trains on British tracks were quickly overcome.[5]

Launch of service

On 14 November 1994, Eurostar services began running from London Waterloo International station in London, to Paris Gare du Nord in Paris, and Brussels-South railway station in Brussels.[3][6][7] The train service started with a limited Discovery service; the full daily service started from 28 May 1995.[8]

In 1995, Eurostar was achieving an average end-to-end speed of 171.5 km/h (106.6 mph) from London to Paris.[9] On 8 January 1996, Eurostar launched services from a second railway station in the UK when Ashford International was opened.[10]

Also in 1996, Eurostar commenced its year-round service to Disneyland with the first train running on 29 June. The following year saw the introduction of services to the French Alps during the winter.[11]

On 20 July 2002 a summer seasonal service to Avignon-Centre was launched. The service ran until 2014 after which it was replaced on 1 May 2015 by an expanded service calling at Avignon TGV and also serving Lyon and Marseille.[11]

On 23 September 2003, passenger services began running on the first completed section of High Speed 1.[4] Following a high-profile glamorous opening ceremony[12] and a large advertising campaign,[13] on 14 November 2007, Eurostar services in London transferred from Waterloo to the extended and extensively refurbished London St Pancras International.[14]

One Way services from London to Amsterdam (returning to Brussels only) were launched on 4 April 2018. This services was made a return service on 26 October 2020.

Records achieved

The Channel Tunnel used by Eurostar services holds the record for having the longest underwater section of any tunnel in the world,[15] and it is the third-longest railway tunnel (behind the Seikan Tunnel and the Gotthard Base Tunnel) in the world.[16]

On 30 July 2003, a Eurostar train set a new British speed record of 334.7 km/h (208.0 mph) on the first section of the "High Speed 1" railway between the Channel Tunnel,[4][6] and Fawkham Junction in north Kent, two months before official public services began running.

On 16 May 2006, Eurostar set a new record for the longest non-stop high-speed journey, a distance of 1,421 kilometres (883 mi) from London to Cannes taking 7 hours 25 minutes.[17]

On 4 September 2007, a record-breaking train left Paris Gare du Nord at 10:44 (09:44 BST) and reached London St Pancras International in 2 hours 3 minutes 39 seconds,[18] carrying journalists and railway workers. This record trip was also the first passenger-carrying arrival at the new London St Pancras International station.[19] On 20 September 2007, Eurostar broke another record when it completed the journey from Brussels to London in 1 hour 43 minutes.[20]

Regional Eurostar and Nightstar

The original proposals for Eurostar included direct services to Paris and Brussels from cities north of London: Manchester Piccadilly via Birmingham New Street on the West Coast Main Line and Leeds and Glasgow Central via Edinburgh Waverley, Newcastle and York on the East Coast Main Line.[21]

Seven 14-coach "North of London" Eurostar trains for these Regional Eurostar services were built, but these services never came to fruition. Predicted journey times of almost nine hours for Glasgow to Paris at the time of growth of low-cost air travel during the 1990s made the plans commercially unviable against the cheaper and quicker airlines.[22] Other reasons that have been suggested for these services having never been run were both government policies and the disruptive privatisation of British Rail.[23] Three of the Regional Eurostar units were leased by Great North Eastern Railway (GNER) to increase domestic services from London King's Cross to York and later Leeds.[24][25] The lease expired in December 2005, and most of the NoL sets were transferred to SNCF for TGV services in northern France.[26][27]

An international Nightstar sleeper train was also planned; this would have travelled the same routes as Regional Eurostar, plus the Great Western Main Line to Cardiff Central.[28] These were also deemed commercially unviable, and the scheme was abandoned with no services ever operated. In 2000, the coaches were sold to Via Rail in Canada.[29][30]

Ashford International station

Ashford International station was the original station for Eurostar services in Kent.[31] Once Ebbsfleet International railway station, also designed to serve Kent, had opened, only three trains a day to Paris Nord and one to Disneyland Paris called at Ashford for a considerable period of time. There were fears that services at Ashford International might be further reduced or withdrawn altogether as Eurostar planned to make Ebbsfleet the new regional hub instead.[32][33] However, after a period during which no Brussels trains served the station,[34] to the dissatisfaction of the local communities,[35][36][37] Eurostar reintroduced a single daily Ashford–Brussels service on 23 February 2009.[38][39]

Changes to corporate structure

On 1 September 2010, Eurostar was incorporated as a single corporate entity, Eurostar International Limited (EIL), replacing the joint operation between EUKL, SNCF and SNCB/NMBS.[40] EIL is owned by SNCF (55%), Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ) (30%), Hermes Infrastructure (10%) and SNCB (5%).[41][42][43]

In June 2014, the UK shareholding in Eurostar International Limited was transferred from London and Continental Railways / Department for Transport to HM Treasury.[44] That October, it was announced that the UK government planned to raise £300 million by selling its stake.[45] In March 2015, the UK government announced that it would sell its 40% share to an Anglo-Canadian consortium made up of the Caisse and Hermes Infrastructure. The sale was completed in May 2015.[42]

Rules for cycles on trains

In 2015, Eurostar threatened to require that cyclists take apart bicycles before they could be transported on the trains. Following criticism from Boris Johnson and cycling groups, Eurostar reversed the plans.[46]

Wi-Fi and onboard entertainment

By March 2016, onboard entertainment was provided by GoMedia, including Wi-Fi connectivity and up to 300 hours of movies and television kept on the train's servers and accessed using the passenger's own devices: mobile phones, tablets, laptops etc. A tracker app allows customers to see where they are.[47]

Merger with Thalys

On 27 September 2019, the heads of two of Eurostar's major shareholders, Guillaume Pepy of SNCF, and the chair of SNCB, Sophie Dutordoir, publicised that Eurostar was planning to come together with its sister company the Franco-Belgian transnational rail service Thalys.[48][49] The arrangement is to merge their operations under the working title of "Green Speed" and expand services outside the core London-Paris-Brussels-Amsterdam service, to create a grand Western European high-speed rail service covering the UK, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany, serving up to 30 million customers by 2030.[50]

As of 2019, Thalys assisted Eurostar with onwards connections between Amsterdam and Brussels, and to provide the Amsterdam to London service, in lieu of passport and customs checks at Amsterdam Centraal station.

In September 2020, the merger between Thalys and Eurostar International was confirmed,[51] a year after Thalys announced its intention to merge with the cross-Channel provider subject to gaining European Commission clearance, to form "Green Speed". SNCF and SNCB already hold a controlling shareholding in Eurostar. In October 2021, it was announced that, following the completion of the merger, the Thalys brand would be discontinued, with all of the new operation's services to be operated under the Eurostar name but with each service's own liveries.[52]

Eurostar is also intending to merge with Thalys administratively, combining ticket sales in a single system.[53]

COVID-19 Impact

By January 2021, Eurostar ridership went down to less than 1% of pre-pandemic levels.[54] The combined financial troubles and lack of ridership caused by the COVID-19 pandemic led to Eurostar seeking governmental assistance from Britain's Treasury and Department for Transport, even though Britain sold its 40% Eurostar holding in 2015.[54][55][56] Eurostar's appeal included granting the company access to Bank of England-backed loans and a temporary reduction in track access charges for use of the UK's high-speed rail line.[54] Despite being majority-owned by the French state railway, SNCF, Eurostar was thought to have already exhausted options for governmental assistance from Paris,[57] but both the French transport minister and the UK Department for Transport confirmed they were working on further plans to maintain the service.

In March 2020, Eurostar placed all of their Class 373 or E300 into storage due to reduced operations. As of January 2022 the sets recommenced testing on HS1, before returning to service on 21 February.[58]

Mainline routes

Eurostar services | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fastest timetabled journeys from London St Pancras | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

LGV Nord (France)

LGV Nord is a French 333-kilometre (207 mi)-long high-speed rail line that connects Paris to the Belgian border and the Channel Tunnel via Lille. It opened in 1993.[63] Its extensions to Belgium and towards Paris, as well as connecting to the Channel Tunnel, have made LGV Nord a part of every Eurostar journey undertaken. A Belgian high-speed line, HSL 1, was added to the end of LGV Nord, at the Belgian border, in 1997. Of all French high-speed lines, LGV Nord sees the widest variety of high-speed rolling stock and is quite busy; a proposed cut-off bypassing Lille, which would reduce Eurostar journey times to Paris, is called LGV Picardie.

Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel is the most important part of the route as it is the only rail connection between Great Britain and the European mainland. It joins LGV Nord in France with High Speed One in Britain. Tunnelling began in 1988, and the 50.5-kilometre (31.4 mi) tunnel was officially opened by British sovereign Queen Elizabeth II and the French President François Mitterrand at a ceremony in Calais on 6 May 1994.[2] It is owned by Getlink, which charges a significant toll to Eurostar for its use.[64] In 1996, the American Society of Civil Engineers named the tunnel as one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World.[65] Along the current route of the Eurostar service, line speeds are 300 kilometres per hour (186 mph) except within the Channel Tunnel, where a reduced speed of 160 kilometres per hour (100 mph) applies for safety reasons.[66][67] Since the launch of Eurostar services, severe disruptions and cancellations have been caused by fires breaking out within the Channel Tunnel, such as in 1996,[68] 2006 (minor),[69] 2008 and 2015.[70]

HSL 1 (Belgium)

Until the opening on 2 June 1996, of the first phase of the Belgian high speed line,[71] Eurostar trains were routed via the Belgian railway line 94. The Eurostar routes still use the line as a diversion if engineering works are taking place on HSL1, depending where it is. The 06:13 from London St Pancras to Brussels still uses the line as a diversion to bypass the peak time disruptions on HSL1 due to the extra TGV services from Brussels for the commuters. After 2 June 1996, some Eurostars to Brussels were routed via the first phase of the Belgian High Speed line and the Belgian railway line 78 via Mons. Although this line is still as a diversion if HSL1 is doing engineering, also depending where the maintenance is taking place.[8] Journey times between London and Brussels were improved when an 88-kilometre (55 mi) Belgian high-speed line, HSL 1, opened on 14 December 1997.[72][73] It links with LGV Nord on the border with France, allowing Eurostar trains heading to Brussels to make the transition between the two without having to reduce speed. A further four-minute improvement for London–Brussels trains was achieved in December 2006, with the opening of the 435-metre (1,427 ft) Brussels South Viaduct.[74] Linking the international platforms of Brussels-South railway station with the high-speed line, the viaduct separates Eurostar (and Thalys) from local services.

High Speed 1 (United Kingdom)

High Speed 1 (HS1), formerly known as the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL), is a 108-kilometre (67 mi) high-speed railway line running from London through Kent to the British end of the Channel Tunnel.[75][76] It was built in two stages. The first section between the tunnel and Fawkham Junction in north Kent opened in September 2003, cutting London–Paris journey times by 21 minutes to 2 hours 35 minutes, and London–Brussels to 2 hours 20 minutes. On 14 November 2007, commercial services began over the whole of the new HS1 line. The redeveloped St Pancras International station became the new London terminus for all Eurostar services.[77] The completion of High Speed 1 has brought the British part of Eurostar's route up to the same standards as the French and Belgian high-speed lines. Non-stop journey times were reduced by a further 20 minutes to 2 hours 15 minutes for London–Paris and 1 hour 51 minutes for London–Brussels.[78][79] As of Autumn 2020, HS1 is the UK's first renewable-powered railway.[80]

Services

Frequency

Eurostar offers up to fifteen weekday London – Paris services (nineteen on Fridays) including nine non-stop (thirteen on Fridays). There are also nine (ten on Friday) London–Brussels services, of which two run non-stop (continuing to Amsterdam) and a further two call at Lille only. One service daily operates to Amsterdam via Brussels and Rotterdam, also calling at Lille.[81][82] In addition, there is a return trip from London to Marne-la-Vallée - Chessy for Disneyland Paris,[83] which runs 4 times a week with increased frequency during school holidays, however this will cease from 6 June 2023 and its future is unknown.[84] There are also seasonal services: in the winter, "Snow trains",[85] aimed at skiers, to Bourg-Saint-Maurice, Aime-la-Plagne and Moûtiers in the Alps; these run weekly, arriving in the alps in the evening and leaving the same evening to arrive in London the following morning.[86] In February 2018, Eurostar announced the start of its long-planned service from London to Amsterdam, with an initial two trains per day from April of that year running between St Pancras and Amsterdam Centraal. This launched as a one-way service, with return trains carrying passengers to Rotterdam and Brussels Midi/Zuid, making a 28-minute stop (which was not deemed long enough to process UK-bound passengers) and then carrying different passengers from Brussels to London.[87] Initially passengers travelling back took a Thalys service to Brussels Midi/Zuid where they could join the Eurostar. This was due to the lack of facilities for juxtaposed controls by the UK Border Force at Amsterdam Centraal and Rotterdam Centraal. On 4 February 2020, the Dutch Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management, Cora van Nieuwenhuizen, and the UK Transport Secretary, Grant Shapps, announced that juxtaposed controls would be established at Amsterdam Centraal and Rotterdam Centraal. The direct train from Amsterdam was originally due to launch on 30 April 2020, and from Rotterdam on 18 May 2020,[88][89] although it was later postponed to 26 October 2020 for both cities due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[90][91]

Since 14 November 2007, all Eurostar trains have been routed via High Speed 1 to or from the redeveloped London terminus at St Pancras International, which at a cost of £800 million was extensively rebuilt and extended to cope with 394-metre (431 yd) long Eurostar trains.[14][92][93] It had been intended to retain some Eurostar services at Waterloo International, but this was ruled out on cost grounds.[94] Completion of High Speed 1 increased the potential number of trains serving London. Separation of Eurostar from British domestic services through Kent meant that timetabling was no longer affected by peak-hour restrictions.

Fares

Eurostar's fares were significantly higher in its early years; the cheapest fare in 1994 was £99 return.[95] In 2002, Eurostar was planning cheaper fares, an example of which was an offer of £50-day returns from London to Paris or Brussels. By March 2003, the cheapest fare from the UK was £59 return, available all year around.[95] In June 2009 it was announced that one-way single fares would be available at £31 at the cheapest. Competition between Eurostar and airline services was a large factor in ticket prices being reduced from the initial levels.[96][97] Business Premier fares also slightly undercut air fares on similar routes, targeted at regular business travellers.[98] In 2009, Eurostar greatly increased its budget ticket availability to help maintain and grow its dominant market share. The Eurostar ticketing system is very complex, being distributed through no fewer than 48 individual sales systems.[99] Eurostar is a member of the Amadeus CRS distribution system, making its tickets available alongside those of airlines worldwide.[100]

Eurostar has two sub-classes of first class: Standard Premier and Business Premier; benefits include guaranteed faster checking-in and meals served at-seat, as well as the improved furnishings and interior of carriages.[101] The rebranding is part of Eurostar's marketing drive to attract more business professionals.[102] Increasingly, business people in a group have been chartering private carriages as opposed to individual seats on the train.[103]

Service connections

Without the operation of Regional Eurostar services using the North of London trainsets across the rest of Britain, Eurostar has developed its connections with other transport services instead, such as integrating effectively with traditional UK rail operators' schedules and routes, making it possible for passengers to use Eurostar as a quick connection to further destinations on the continent.[104] All three main terminals used by the Eurostar service – St Pancras International, Paris Gare du Nord, and Brussels Midi/Zuid – are served by domestic trains and by local urban transport networks such as the London Underground and the Paris Metro. Standard Eurostar tickets no longer include free onward connections to or from any other station in Belgium: this is now available for a flat-rate supplement, currently £5.50.[105]

Eurostar has announced several partnerships with other rail services,[106] most notably Thalys connections at Lille and Brussels for passengers to go beyond current Eurostar routes towards the Netherlands and Germany.[107] In 2002, Eurostar initiated the Eurostar-Plus program, offering connecting tickets for onward journeys from Lille and Paris to dozens of destinations in France. Through fares are also available from 68 British towns and cities to destinations in France and Belgium.[108] In May 2009 Eurostar announced that a formal connection to Switzerland had been established in a partnership between Eurostar and Lyria, which will operate TGV services from Lille to the Swiss Alps for Eurostar connection.[109][110][111]

In May 2019, Eurostar ended its agreement with Deutsche Bahn that allowed passengers to travel by train from the UK to Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Under the agreement passengers could travel on a single booking which made rescheduling easier. However, the direct tickets ceased to be sold from 9 November 2019.[112]

Controls and security

Because the UK is not part of the European Union or the Schengen Area,[113] and because the Netherlands, Belgium and France are not part of the Common Travel Area, all Eurostar passengers must go through border controls. Both the British Government and the Schengen governments concerned (Belgium, Netherlands and France) have legal obligations to check the travel documents of those entering and leaving their respective countries.

To allow passengers to walk off the train without arrival checks in most cases, juxtaposed controls ordinarily take place at the embarkation station.

To comply with UK law,[114] there are full security checks similar to those at airports, scanning both bags and people's pockets. The recommended check-in time is 90–120 minutes except for business class where it is 45–60 minutes; these are much longer than previously because of extra checks in place due to Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic.[115]

Eurostar passengers travelling within the Schengen area on trains towards London bypass border checks, and enter the preallocated cars at the rear of the train, which are reserved for these passengers. This area is then searched at Lille and all passengers removed. This arrangement was set up after numerous people entered the UK without prior authorisation, by buying a ticket from Brussels to Lille or Calais but remaining on the train until London – an issue exacerbated by Belgian police threatening to arrest UK Border Agency staff at Brussels-Midi if they tried to prevent passengers whom they suspected of attempting to exploit this loophole from boarding Eurostar trains.[116] Travel from Calais or Lille towards Brussels and the Netherlands has no border or security control. On 7 July 2020 a modified agreement was signed in Brussels that includes The Netherlands in the previous agreement. This allows for juxtaposed controls in Amsterdam and Rotterdam like those in Brussels and Paris.[117]

When the tripartite agreements were signed, the Belgian Government said that it had serious questions about the compatibility of this agreement with the Schengen Convention and the principle of free movement of people enshrined in various European treaties.[118] On 30 June 2009 Eurostar raised concerns at the UK House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee that it was illegal under French law to collect the information required by the UK government under the e-Borders scheme, and the company would be unable to cooperate.[119][120]

On the northbound Disneyland and ski trains, the security check and French passport check take place at the origin, while the UK passport check takes place at the UK arrival stations. These are the only route where passengers are not cleared by UK border officials before crossing the Channel.

On the northbound Marseille-London train, there is no facility for security or passport checks at the southern French stations, so passengers must leave the train at Lille-Europe, taking all their belongings with them, and undergo security and border checks there before rejoining the train which waits at the station for just over an hour.[121]

On several occasions, people have tried to stow away illegally on board the train,[122] sometimes in large groups,[123] trying to enter the UK; border monitoring and security is therefore extremely tight.[124] Eurostar claims to have good and well-funded security measures.[125]

Operational performance

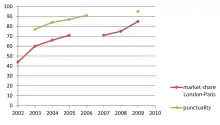

Eurostar's punctuality has fluctuated from year to year, but usually remains over 90%;[126] in the first quarter of 1999, 89% of services operated were on time, and in the second quarter it reached 92%.[127] Eurostar's best punctuality record was 97.35%, between 16 and 22 August 2004.[4] In 2006, it was 92.7%,[128] and in 2007, 91.5% were on time.[129][130] In the first quarter of 2009, 96% of Eurostar services were punctual, compared with rival air routes' 76%.[131]

An advantage held by Eurostar is the convenience and speed of the service: with shorter check-in times than at most airports and hence quicker boarding and less queueing[132][133] and high punctuality, it takes less time to travel between central London and central Paris by high-speed rail than by air. Eurostar now has a dominant share of the combined rail–air market on its routes to Paris and Brussels. In 2004, it had a 66% share of the London–Paris market, and a 59% share of the London–Brussels market.[134] In 2007, it achieved record market shares of 71% for London–Paris and 65% for London–Brussels routes.[135]

Eurostar's passenger numbers initially failed to meet predictions. In 1996, London and Continental Railways forecast that passenger numbers would reach 21.4 million annually by 2004,[136] but only 7.3 million was achieved. 82 million passengers used Waterloo International Station from its opening in 1994 to its closure in 2007.[6] 2008 was a record year for Eurostar, with a 10.3% rise in passenger use, which was attributed to the use of High Speed 1 and the move to St Pancras.[137] The following year, Eurostar saw an 11.5% fall in passenger numbers[138] during the first three months of 2009, attributed to the 2008 Channel Tunnel fire[70] and the 2009 recession.[139]

As a result of the poor economic conditions, Eurostar received state aid in May 2009 to cancel out some of the accumulated debt from the High Speed 1 construction programme.[140] Later that year, during snowy conditions in the run-up to Christmas, thousands of passengers were left stranded as several trains broke down and many more were cancelled. In an independent review commissioned by Eurostar, the company came in for serious criticism about its handling of the incident and lack of plans for such a scenario.[141]

In 2006, the Department for Transport predicted that, by 2037, annual cross-channel passenger numbers would probably reach 16 million,[142] considerably less optimistic than London and Continental Railways's original 1996 forecast.[136] In 2007 Eurostar set a target of carrying 10 million passengers by 2010.[143] The company cited several factors to support this objective, such as improved journey times, punctuality and station facilities. Passengers in general, it stated, are becoming increasingly aware of the environmental effects of air travel, and Eurostar services emit much less carbon dioxide.[144] and that its remaining carbon emissions are now offset, making its services carbon neutral.[145][146] Further expansion of the high-speed rail network in Europe, such as the HSL-Zuid line between Belgium and the Netherlands, continues to bring more destinations within rail-competitive range, giving Eurostar the possibility of opening up new services in future.

The following chart presents the estimated number of passengers annually transported by the Eurostar service since 1995: [147][148][149][150][151][152][153][154]

Awards and accolades

Eurostar has been hailed as having set new standards in international rail travel and has won praise several times over for its high standards.[155][156][157] However, Eurostar had previously struggled with its reputation and brand image. One commentator had defined the situation at the time as:[158]

In June 2003, Eurostar was battling to recover from the worst period in its 10-year history. Negative media coverage combined with poor sales and the general public's low opinion of the British rail industry, created a major challenge... Eurostar was finding it difficult to pick itself up from one of the worst periods in its decade-long history. The period post 9/11 had sent the business into a downturn. Passenger numbers were drying up due to worries over international travel. Several management changes had led to a pause in strategy. Punctuality had suffered badly because of wider problems with the UK's rail infrastructure.

Eurostar won the Train Operator of the Year award in the HSBC Rail Awards for 2005.[106] In 2006, Eurostar's Environment Group was set up,[159] with the aim of making changes in the Eurostar services' daily running to decrease negative environmental impact.[160] The organization set itself a target of reducing carbon emissions per passenger journey by 25% by 2012.[160] Drivers were trained in techniques to achieve maximum energy efficiency, and lighting was minimised; the provider of the bulk of the energy for the Channel Tunnel was switched to nuclear power stations in France.[160] Eurostar's target was to reduce emissions by 35 percent per passenger journey by 2012, putting itself beyond the efforts of other railway companies in this field and thereby winning the 2007 Network Rail Efficiency Award.[159] In the grand opening ceremony of St Pancras International, one of the Eurostar trains was given the name 'Tread Lightly', said to symbolise their smaller impact on the environment compared to planes.[161] By 2008, Eurostar's environmental credentials had become highly developed and promoted.[162]

Since then, Eurostar has received multiple awards. It was declared the Best Train Company in the joint Guardian/Observer Travel Awards 2008[163] and earned a spot on the Sunday Times' Best Green Companies List (2009).[164] Other awards include: ICARUS’ Environmental Award for Best Rail Provider (2009),[165] Guardian & Observer Travel Award for Best Train Company (2009),[166] Travel Weekly's Golden Globes Award for Best Rail Operator (2010),[167] World Travel Market's Responsible Tourism Award for Best Low Carbon Initiative (2011),[168] TNT Magazine's Gold Backpack Award for Favourite Travel Transport (2012),[169] World Travel Awards Europe's Leading Passenger Rail Operator (2011),[170] National Rail Awards Train of the Year (2017),[171] PETA's Travel Award for Best Travel Experience (2019),[172] Mobile Industry Awards' Distributor of the Year (2020).[173]

Environmental Initiatives

In 2007, Eurostar became the world's first carbon-neutral train service through its launch of "Tread Lightly," an environmental programme with the goal of reducing the service's carbon-dioxide emissions by 25% by 2012.[174][175] The programme included: reducing power consumption on its rolling stock; sourcing more electricity from lower-emission generators; adding new controls on lighting, heating, and air conditioning; reducing paper usage via electronic tickets; recycling water and employee uniforms; sourcing all food on board from Britain, France, or Belgium.[175] Eurostar also funded three renewable energy projects in developing regions around the world: a windfarm in Tamil Nadu, India; a micro-hydropower project in China; and a plan specifying improvements on fuel consumption of three-wheeler taxis in Indonesia.[174]

In 2019, Eurostar removed all single-use plastics from its trains between London and Paris.[176] Now the trains serve only wooden cutlery, recyclable cans of water, glass wine bottles, paper-based coffee cups, and eco-friendly food packaging.[176][177][178] Eurostar partnered with the Woodland Trust, ReforestAction, and Trees for All in 2020, with the goal of planting 20,000 trees each year in woodlands along its routes across the UK, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Since Tread Lightly launched, Eurostar has reduced its carbon footprint by over 40% and now emits up to 90% less greenhouse gas emissions than the equivalent flight.[176][177][178]

Organisation

Since 2010, Eurostar has been operated by Eurostar International Limited (EIL), a company owned since April 2022 by Eurostar Group.

Railteam

Eurostar is a member of Railteam, a marketing alliance formed in July 2007 of seven European high-speed rail operators.[179] The alliance plans to allow tickets to be booked from one end of Europe to the other on a single website.[179] In June 2009 London and Continental Railways, and the Eurostar UK operations they held ownership of, became fully nationalised by the UK government.[180]

Domestic journeys

Eurostar is not permitted to carry passengers on journeys within a country, so passengers cannot travel (for example) from Lille to Marne-la-Vallée–Chessy, London to Ashford, or Rotterdam to Amsterdam. Lille to Brussels is the only international intra-Schengen journey that Eurostar is offering for sale.[181]

Fleet

Fleet details

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Carriages | Number | Unit Nos. | Routes operated | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | ||||||||

| Class 373 Eurostar e300 |

.jpg.webp)  |

Locomotive hauled trainset | 186 | 300 | Two Class 373 locomotives with 18 coaches between them | 12 | 373001-373022 373101-373108 373201-373202 373205-373224 373229-373232 |

London–Paris London–Brussels London–Marne-la-Vallée – Chessy London–Bourg Saint Maurice London–Marseille - Saint-Charles |

1992–1996 |

| Class 374 Eurostar e320 |

|

EMU trainset | 200 | 320 | 16 | 17 | 374001-374034 | London–Paris London–Brussels London–Amsterdam Centraal London–Marne-la-Vallée – Chessy London–Bourg Saint Maurice London–Marseille - Saint-Charles |

2011–2018 |

In addition to its multiple unit fleet units, Eurostar operates a single Class 08 diesel shunter as the pilot at Temple Mills depot.[182]

Class 373

Built between 1992 and 1996, Eurostar's fleet consisted of 38 EMU trains, designated Class 373 in the United Kingdom and TGV TMST in France. The units have also been branded as the Eurostar e300 by Eurostar since 2015. There are two variants:

- 31 "Inter-Capital" sets consisting of two power cars and eighteen passenger carriages. These trains are 394 metres (1,293 ft) long and can carry 750 passengers: 206 in first class, 544 in standard class.[183]

- 7 shorter "North of London" sets which have two power cars and fourteen passenger carriages and are 320 metres (1,050 ft) long. These sets have a capacity of 558 seats: 114 first class, 444 standard and which were designed to operate the aborted Regional Eurostar services.

Each train has a unique four-digit number starting with "3" (3xxx). This designates the train as a Mark 3 TGV (Mark 1 being SNCF TGV Sud-Est; Mark 2 being SNCF TGV Atlantique). The second digit denotes the country of ownership:

- 30xx UK

- 31xx Belgium

- 32xx France

- 33xx Regional Eurostar

The trains are essentially modified TGV sets,[184][185] and can operate at up to 300 kilometres per hour (186 mph) on high-speed lines, and 160 kilometres per hour (100 mph) in the Channel Tunnel.[66][67] It is possible to exceed the 300 km/h speed limit, but only with special permission from the safety authorities in the respective country.[186] Speed limits in the Channel Tunnel are dictated by air-resistance, energy (heat) dissipation and the need to be used with other, slower trains. The trains were designed with Channel Tunnel safety in mind, and consist of two independent "half-sets" each with its own power car.[26][67] In the event of a serious fire on board while travelling through the tunnel, passengers would be transferred into the undamaged half of the train, which would then be detached and driven out of the tunnel to safety.[187] If the undamaged part were the rear half of the train, this would be driven by the Chef du Train, who is a fully authorised driver and occupies the rear driving cab while the train travels through the tunnel for this purpose.[188]

As 27 of the 31 Inter-Capital sets were sufficient to operate the service, four were used by SNCF for domestic TGV services. The Eurostar logos were removed from these sets, but the base colours of white, black, and yellow remained.

As the Class 374 units have entered service the Class 373 fleet has gradually been reduced. 11 remain in regular service with 17 scrapped and 10 in store.

Fleet updates

In 2004–2005 the "Inter-Capital" sets still in daily use for international services were refurbished with a new interior designed by Philippe Starck.[4][189] The original grey-yellow scheme in Standard class and grey-red of First/Premium First were replaced with a grey-brown look in Standard and grey-burnt-orange in First class. Power points were added to seats in First class and coaches 5 and 14 in Standard class. Premium First class was renamed BusinessPremier.

In 2008, Eurostar announced that it would be carrying out a mid-life refurbishment of its Class 373 trains to allow the fleet to remain in service beyond 2020.[190] This will include the 28 units making up the Eurostar fleet, but not the three Class 373/1 units used by SNCF or the seven Class 373/2 "North of London" sets.[191] As part of the refurbishment, the Italian company Pininfarina was contracted to redesign the interiors,[192] and The Yard Creative was selected to design the new buffet cars.[193] On 11 May 2009 Eurostar revealed the new look for its first-class compartments.[194] The first refurbished train was due in service in 2012,[195] and Eurostar planned to complete the entire process by 2014. On 13 November 2014 Eurostar announced the first refurbished trains would not re-enter the fleet until the 3rd or 4th quarter of 2015 due to delays at the completion centre. The last refurbished e300 eventually re-entered service in April 2019.

Class 374

In addition to the announced mid-life update of the existing Class 373 fleet, Eurostar in 2009 reportedly entered prequalification bids for eight new trainsets to be purchased.[196] Any new trains would need to meet the same safety rules governing passage through the Channel Tunnel as the existing Class 373 fleet. The replacement to the Class 373 trains has been decided jointly between the French Transport Ministry and the UK Department for Transport. The new trains will be equipped to use the new ERTMS in-cab signalling system, due to be fitted to High Speed 1 around 2040.[197]

On 7 October 2010, it was reported that Eurostar had selected Siemens as preferred bidder to supply 10 Siemens Velaro e320[198] trainsets at a cost of €600 million (and a total investment of more than £700 million with the refurbishment of the existing fleet included)[199] to operate an expanded route network, including services from London to Cologne and Amsterdam.[200] These would be sixteen-car, 400-metre (1,312 ft) long trainsets built to meet current Channel Tunnel regulations.[200] The top speed will be 320 km/h (200 mph) and they will have 894–950 seats, unlike the current fleet built by the French company Alstom, which has a top speed of 300 km/h (186 mph) and a seating capacity of 750. Total traction power will be rated at 16 MW.[198][201][202][203]

The nomination of Siemens would see it break into the French high-speed market for the first time, as all French and French subsidiary high-speed operators use TGV derivatives produced by Alstom.[204] Alstom attempted legal action to prevent Eurostar from acquiring German-built trains, claiming that the Siemens sets ordered would breach Channel Tunnel safety rules,[205] but this was thrown out of court.[206] Alstom said, after its High Court defeat, that it would "pursue alternative legal options to uphold its position". On 4 November 2010, the company lodged a complaint with the European Commission over the tendering process, which then asked the British government for "clarification".[207] Alstom then announced it had started legal action against Eurostar, again in the High Court in London.[208] In July 2011, the High Court rejected Alstom's claim that the tender process was "ineffective",[209] and in April 2012 Alstom said it would call off pending court actions against Siemens.[210] This effectively freed the way for Siemens to build the new Eurostar trains,[211] the first of which were expected to enter service in late 2015.[212]

On 13 November 2014 Eurostar announced the purchase of an additional seven e320s for delivery in the second half of 2016. At the same time, Eurostar announced the first five e320s from the original order of ten would be available by December 2015, with the remaining five entering service by May 2016. Of the five sets ready by December 2015, three of them were planned to be used on London-Paris and London-Brussels routes.[213]

Past fleet

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Number operated |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | |||||

| Class 37 |  |

Diesel locomotive | 90 | 145 | 12 | Intended to operate sleeper services over non-electrified parts of the railway network in Britain. Eurostar retained three locomotives for the rescue of failed trains, route learning and driver training, but sold them to Direct Rail Services when the new Temple Mills Depot opened in November 2007.[214] |

| Class 73 |  |

Electro-diesel locomotive | 90 | 145 | 2 | Were used primarily to rescue failed trains. Eurostar operated two of these from its North Pole depot until 2007, when they were loaned to a pair of educational initiatives having become redundant following the move to Temple Mills.[215][216] |

| Class 92 |  |

Electric locomotive | 87 | 140 | 7 | Intended to operate the Nightstar sleeper services. Eurostar owned seven units of this class, which never saw service until they were sold in 2007 to Europorte 2.[217] |

| Class 373 Eurostar e300 |  |

EMU | 186 | 300 | 38 | 11 in operation, 10 in storage, 17 scrapped, 4 power cars preserved. |

Possible use of double-deck trains

In 2005, the chief executive of Eurostar, Richard Brown, suggested that existing Eurostar trains could be replaced by double-deck trains similar to the TGV Duplex units when they are withdrawn from service. According to Brown, a double-deck fleet could carry 40 million passengers per year from Britain to Continental Europe, equivalent to adding an extra runway at a London airport.[218]

Accidents, incidents and events

A number of technical incidents have affected Eurostar services over the years, but up to the present there has only been one major accident involving a service operated by Eurostar, a derailment in June 2000. Other incidents in the Channel Tunnel – such as the 1996 and 2008 Channel Tunnel fires – have affected Eurostar services but were not directly related to Eurostar's operations. However, the breakdowns in the tunnel, which resulted in cessation of service and inconvenience to thousands of passengers, in the run-up to Christmas 2009, proved a public-relations disaster.[219]

Minor incidents

There have been several minor incidents with a few Eurostar services. In October 1994 there were teething problems relating to the start of operations. The first preview train, carrying 400 members of the press and media, was delayed for two hours by technical problems.[5][220][221][222] On 29 May 2002 a Eurostar train was initially sent down a wrong line – towards London Victoria railway station instead of London Waterloo – causing the service to arrive 25 minutes late. A signalling error that led to the incorrect routeing was stated to have caused "no risk" as a result.[223]

On 11 April 2006, a house collapsed next to a railway line near London which caused Eurostar services to have to terminate and start from Ashford International instead of London Waterloo. Passengers waiting at Waterloo International were initially directed on to local trains towards Ashford leaving from the adjacent London Waterloo East railway station, until overcrowding occurred at Ashford.[224]

1996

Approximately 1,000 passengers were trapped in darkness for several hours inside two Eurostar trains on the night of 19/20 February 1996. The trains stopped inside the tunnels due to electronic failures caused by snow and ice. Questions were raised at the time about the ability of the train and tunnel electronics to withstand the mix of snow, salt and ice which collect in the tunnels during periods of extreme cold.[225]

2000

On 5 June 2000 a Eurostar train travelling from Paris to London derailed on the LGV Nord high-speed line while traveling at 290 km/h (180 mph). Fourteen people were treated for light injuries or shock, with no fatalities or major injuries. The articulated nature of the trainset was credited with maintaining stability during the incident and all of the train stayed upright.[226] The incident was caused by a traction link on the second bogie of the front power car coming loose, leading to components of the transmission system on that bogie impacting the track.[220]

2007

The first departures from St Pancras on 14 November 2007 coincided with an open-ended strike by French rail unions as part of general strike actions over proposed public-sector pension reforms. The trains were operated by uninvolved British employees and service was not interrupted.[77]

2009

On 23 September 2009 an overhead power line dropped on to a Class 373 train arriving at St Pancras station, activating a circuit breaker and delaying eleven other trains.[227] Two days later, on 25 September 2009, electrical power via the overhead lines was lost on a section of high-speed line outside Lille, delaying passengers on two evening Eurostar-operated services.[228]

During the December 2009 European snowfall, five Eurostar trains broke down inside the Channel Tunnel, after leaving France, and one in Kent on 18 December. Although the trains had been winterised, the systems had not coped with the conditions.[229] Over 2,000 passengers were stuck inside failed trains inside the tunnel, and over 75,000 had their services disrupted.[230] All Eurostar services were cancelled from Saturday 19 December to Monday 21 December 2009.[231] An independent review, published on 12 February 2010, was critical of the contingency plans in place for assisting passengers stranded by the delays, calling them "insufficient".[232][233]

2010

On 7 January 2010 a Brussels-London train broke down in the Channel Tunnel,[234] resulting in three other trains failing to complete their journeys.[235] The cause of the failure was the onboard signalling system.[236] Due to the severe weather, a limited service was operated in the next few days.[237][238]

On 15 February 2010, services between Brussels and London were interrupted following the Halle train collision, this time after the dedicated HSL 1 lines in the suburbs of the Belgian capital were blocked by debris from a serious train crash on the suburban commuter lines alongside.[239] No efforts were made to reroute trains around the blockage; Eurostar instead terminated services to Brussels at Lille, directing passengers to continue their journey on local trains. Brussels services resumed on a limited scale on 22 February.

On 21 February 2010 the 21:43 service from Paris to London broke down just outside Ashford International,[240] stranding 740 passengers for several hours while a rescue train was called in.

On 15 April 2010 air traffic in Western Europe closed because of the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano. Many travellers between the UK and the European mainland instead took the Eurostar train, all tickets between Brussels and London on 15 and 16 April being sold out within 3½ hours after the closure of British airspace. [241] Between 15 and 20 April, Eurostar put on 33 additional trains and carried 165,000 passengers – 50,000 more than had been scheduled to travel during this period.

On 20 December 2010, the Channel Tunnel was closed off for a day due to snowy weather. Eurostar Trains were suspended that day with thousands of passengers stranded in the run up to Christmas.

2011

On 17 October 2011 a man fell from the 17:04 service from London to Brussels as it passed through Westenhanger and Cheriton in Folkestone, near the entry to the Channel Tunnel.[242] The individual was an Albanian who had been refused entry to the United Kingdom and was voluntarily returning to Brussels. He was pronounced dead at the scene. The line was closed for several hours following the incident.[243] The train itself returned north to Ashford International, where passengers were transferred to a Eurostar service operating from Marne-la-Vallée to London.[243]

Possible developments

Stratford International station

Eurostar trains do not currently call at Stratford International, which was intended to be a London stop for the regional Eurostars when the station was constructed.[244] This was to be reviewed following the 2012 Olympics.[245] However, in 2013, Eurostar claimed that its 'business would be hit' by stopping trains there.[246]

Regional Eurostar

Although the original plan for Regional Eurostar services to destinations north of London was abandoned,[23] the significantly improved journey times available since the opening of High Speed 1 — which is physically connected to both the East Coast Main Line and the North London Line (for the West Coast Main Line) at London St Pancras International – and the increased maximum speeds on the West Coast Main Line since the 2000s may make potential Regional Eurostar services more commercially viable. This would be even more likely if proposals are adopted for a new high-speed line from London to the north of Britain.[247] Simon Montague, Eurostar's Director of Communications, commented that: "...International services to the regions are only likely once High Speed 2 is built."[248] However, as of 2014 the current plans for High Speed 2 do not allow for a direct rail link between that new line, and High Speed 1, meaning passengers would still be required to change at London Euston and take some form of transportation to London St Pancras International.[249]

Key pieces of infrastructure still belong to LCR via its subsidiary London & Continental Stations and Property, such as the Manchester International Depot, and Eurostar (UK) still owns several track access rights and the rights to paths on both the East Coast Main Line and the West Coast Main Line.[250][251] While no announcement has been made of plans to start Regional Eurostar services, it remains a possibility for the future. In the meantime, the closest equivalent to Regional Eurostar services are same-station connections with East Midlands Railway and Thameslink, changing at London St Pancras International. The construction of a new concourse at adjacent London King's Cross improved interchange with St Pancras and provided London North Eastern Railway, Great Northern, Hull Trains and Grand Central services with easier connections to Eurostar.

High Speed 2

Eurostar has already been involved in reviewing and publishing reports into High Speed 2 for the British Government[252] and looks favourably upon such an undertaking. The operation of Regional Eurostar services will not be considered until such time as High Speed 2 has been completed.[248] Alternatively, future loans of the North of London sets to other operators would enable the trains to operate at their full speed, unlike GNER's previous loan between 2000 and 2005, where the trains were limited to 175 km/h (109 mph) on regular track.

LGV Picardie

LGV Picardie is a proposed high-speed line between Paris and Calais via Amiens. By cutting off the corner of the LGV Nord at Lille, it would enable Eurostar trains to save 20 minutes on the journey between Paris and Calais, bringing the London–Paris journey time under 2 hours. In 2008 the French Government announced its future investment plans for new LGVs to be built up to 2020; LGV Picardie was not included but was listed as planned in the longer term.[253]

Operational difficulties with cross-border trains

"We know we can go to most places in France physically, because our trains are compatible with French infrastructure, but then you've got to look at impact on fleet utilisation, you've got to have a station that's got the spare capacity to have a train stood for a number of hours, for all the security, screening, passport control passes. So it's not possible to go just anywhere. And you've got to be able to get the control authorities to agree that there's a big enough market for it to be worthwhile for them to set up there."

Richard Brown, Chief Executive of Eurostar.[254]

The reduced journey times offered by the opening of High Speed 1[78] and the opening of the LGV Est and HSL-Zuid bring more continental destinations[255] within a range from London where rail is competitive with air travel. By Eurostar's estimates a train would then take 3 hours 30 minutes from London to Amsterdam.[256] At present Eurostar is concentrating on developing its connections with other services,[106][107] but direct services to other destinations would be possible. With the new e320 rolling stock allowed Eurostar to enter the Netherlands and possibly Germany in future. In additional with every new country Eurostar enters there are security issues, due to the UK's not having signed up to the Schengen Agreement,[113] which allows unrestricted movement across borders of member countries. For example, the Amsterdam to London route was previously direct in only one way, with people needing to get a train to Brussels to go through the juxtaposed controls; the direct connection was subject to talks between the UK and Dutch governments, and became completed in 2020 for services to start.

The difficulties that Eurostar faces in expanding its services would also be faced by any potential competitors to Eurostar. As the UK is outside the Schengen Agreement, London-bound trains must use platforms that are physically isolated,[187] a constraint which other international operators such as Thalys do not face. In addition, the British authorities are required to make passenger security and passport checks before they board the train,[257] which might deter domestic passengers. Compounding the difficulties in providing a similar service are the Channel Tunnel safety rules, the major ones being the "half-train rule" and the "length rule". The "half-train rule" stipulated that passenger trains had to be able to split in the case of emergency.[67] Class 373 trains were designed as two half-sets, which when coupled form a complete train, enabling them to be split easily in the event of an emergency while in the tunnel, with the unaffected set able to be driven out. The half-train rule was finally abolished in May 2010. However, the "length rule", which states that passenger trains must be at least 375 metres long with a through corridor (to match the distance between the safety doors in the tunnel), was retained, preventing any potential operators from applying to run services with existing fleets (the majority of both TGV and ICE trains are only 200m long).[258]

Eurostar expansion

At the same time as Pepy's announcement, Richard Brown announced that Eurostar's plans for expanding its network potentially included Amsterdam and Rotterdam as destinations, using the HSL Zuid line. This would require either equipment upgrades of the existing fleet, or a new fleet equipped for both ERTMS and the domestic signalling systems used by Nederlandse Spoorwegen.[259] Following the December 2009 opening of HSL Zuid, a London–Amsterdam journey is estimated to take 4 hr 16 min.[260]

In an interview with Eurostar's Chief Executive Nicolas Petrovic in the Financial Times in May 2012, an intention for Eurostar to serve ten new destinations was expressed, including Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Cologne, Lyon, Marseille and Geneva, along with a likely second hub to be created in Brussels.[261][262]

In March 2016 in an interview with Bloomberg, Eurostar's Chief Executive expressed interest in operating a direct train service between London and Bordeaux, but not before 2019. Journey time was said to be around four and a half hours using the new LGV Sud Europe Atlantique.[263]

Southern France

In December 2012 Eurostar announced that on Saturdays during May 2013–June 2013 a new seasonal service would be introduced to Aix-en-Provence, also serving Lyon-Part-Dieu and Avignon TGV on the way (the latter being 6 kilometres (4 miles) from central Avignon). This was in addition to the seasonal service launched in 2002 which ran on Saturdays during July and August and the first week of September travelling to Avignon-Centre.[264] The Aix-en-Provence services did not run in 2014 but was replaced along with the seasonal Avignon Centre services with the new year-round service to Lyon, Avignon and Marseille as of 1 May 2015.[213]

The winter service ended in November 2017, meaning that - from 2018 - these services ran only from May to September,[265][266] with connections during the rest of the year being offered via Eurostar, but requiring a change to SNCF trains in Paris or Lille.[267] Travel time from London to Marseille was roughly 6.5 hours in 2018.[266] These services have been suspended since 2019.

Netherlands

In September 2013, Eurostar announced an agreement with the Government of Netherlands and NS, the Dutch railway company, to start twice daily services between London and Amsterdam Centraal; the launch was initially planned for December 2016. The service will use the newly bought Siemens Velaro trainsets and will also call at Brussels, and Rotterdam. The journey time will be around four hours.[268]

Initially, trains stop in Brussels for about half an hour to allow domestic passengers from Amsterdam and Rotterdam to leave and allow London bound passengers to board.[269] Eventually, Passengers for London from Amsterdam and Rotterdam will undertake all security checks before boarding and will be able to travel direct both ways. The trains will also convey passengers from the Netherlands on journeys to Brussels who will not need to pass through security and they will be allocated half the train which will be kept separate from the London-bound passengers by locking the intermediate door. The Brussels-bound half of the train will be security swept on arrival at Brussels before Brussels-to-London passengers can board.[270]

The journey from London to Amsterdam Centraal will take 3 hr 41 min and trains will call at Brussels Zuid/Midi and Rotterdam Centraal Station. From Amsterdam Centraal to London St Pancras, trains will take 4 hr 9 min to include the 28-minute stop at Brussels.

In November 2014, Eurostar announced the service to Amsterdam would start in "2016-2017", and would include a stop at Schiphol Airport in addition to the previously announced destinations. Eurostar have indicated that the calling pattern 'is not set in stone' and if a business case supports it the service might be extended to additional cities such as Utrecht.[271]

The service was finally planned to start running on 4 April 2018, with fare prices starting at £35 for a single ticket.[272] An "inaugural train" from St Pancras International to Amsterdam via Rotterdam broke a speed record for the journey to Brussels (1hr 46mins) on 20 February 2018.[272] The first regular service to Amsterdam left St Pancras at 08:31 on 4 April 2018.[273]

The direct Amsterdam to London service launched on 26 October 2020 with two trains a day Monday - Friday.[274] Until that date, a change in Brussels for passport controls and security added about an hour to journey time. Eurostar stated that the new journey time to London was 4 hr 9 min from Amsterdam, and 3 hr 29 min from Rotterdam.

Competition

In 2010, international rail travel was liberalised by new European Union directives, designed to break up monopolies in order to encourage competition for services between countries.[275][276] This sparked interest among other companies in providing services in competition to Eurostar and new services to destinations beyond Paris and Brussels. The only rail carrier to formally propose and secure permission for such a service up to now is Deutsche Bahn, which intends to run services between London and Germany and the Netherlands. The sale of High Speed One by the British Government having effectively nationalised LCR in June 2009 is also likely to stimulate competition on the line.[277]

In March 2010, it was announced that Eurotunnel was in discussions with the Intergovernment Commission, which oversees the tunnel, with the aim of amending elements of the safety code governing the tunnel's usage. Most saliently, the requirement that trains be able to split within the tunnel and each part of the train be driven out to opposite ends has been removed. However, the proposal to allow shorter trains was not passed.[258] Eurotunnel Chairman & Chief Executive Jacques Gounon said that he hoped the liberalisation of rules would allow entry into the market of competitors such as Deutsche Bahn. Sources at Eurotunnel suggested that Deutsche Bahn could have entered the market at the timetable change in December 2012.[278] This, however, did not happen.

In July 2010 Deutsche Bahn (DB) announced that it intended to make a test run with a high-speed ICE-3MF train through the Channel Tunnel in October 2010 in preparation for possible future operations.[279] The trial ran on 19 October 2010 with a Class 406 ICE train specially liveried with a British "Union flag" decal. The train was then put on display for the press at St Pancras International. However, this is not the class of train that would be used for the proposed service. At the St Pancras ceremony, DB revealed that it planned to operate from London to Frankfurt and Amsterdam (two of the biggest air travel markets in Europe), with trains 'splitting & joining' in Brussels. It hoped to begin these services in 2013 using Class 407 ICE units, with three trains per day each way—morning, midday and afternoon. Initially the only calling points would be Rotterdam on the way to Amsterdam, and Cologne on the way to Frankfurt. Amsterdam and Cologne would be under four hours from London, Frankfurt around five hours.[280] DB decided to put this on hold mainly due to advance passport check requirements. DB had hoped that immigration checks could be done on board, but British authorities required immigration and security checks to be done at Lille Europe station, taking at least 30 minutes.[121]

In August 2010, Trenitalia announced its desire to eventually run high-speed trains from Italy to the United Kingdom, using its newly ordered high-speed trains. The trains will be delivered from 2013.[281]

Ridership

Cumulative ridership since 1994 has reached 190 million, 11 million passengers had used its international services during 2018, the highest ever, a 7% increase on the 10.3 million carried in 2017.[282]

References

- Due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, Ebbsfleet and Ashford will not be served by Eurostar trains until 2025.[59]

- Due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, Calais-Fréthun, Lyon Part-Dieu, Avignon TGV, and Marseille, are not served by Eurostar trains for the foreseeable future.[60]

- Due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, Disneyland Paris services will be suspended from 6 June 2023.[61]

- Operated as a charter service for Travelski.[62]

- Noulton, John (February 2001). "The Channel Tunnel" (PDF). Japan Railway & Transport Review (26): 38–45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- "On this day: 6 May 1994: President and Queen open Chunnel (with video clip)". BBC News. 6 May 1994. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- "Our history". Eurotunnel. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- "Our history". Eurostar. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- Wolmar, Christian (21 October 1994). "Channel train opens with a breakdown". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- "Official Waterloo 'Goodbye' video, useful statistics and numbers shown". Youtube.com. 20 December 2007. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "Waterloo International: 1994–2007". The Guardian. London. 13 November 2007. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- "Rail Chronology: Eurostar services". www.railchronology.free-online.co.uk.

- Takagi, Ryo (March 2005). "High-speed Railways:The last ten years" (PDF). Japan Railway & Transport Review (40): 4–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- "Eurostar celebrates 10 years at Ashford International" (Press release). Eurostar. 9 January 2006. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012.

- "Eurostar at 20: how has the service grown?". the Guardian. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Carmichael, Sri; Low, Valentine (7 November 2007). "The royal pride of reborn St Pancras". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- Sweney, Mark (14 July 2007). "Eurostar launches St Pancras ads". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Higham, Nick (6 November 2007). "The transformation of St Pancras". BBC News. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- Gilbert, Jane (1 December 2006). "'Chunnel' workers link France and Britain". The Daily Post. Rotorua, New Zealand: APN New Zealand.

- Minus, Jodie (26 January 2007). "Eurostar an underground force". The Australian. Sydney. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- "Eurostar sets new Guinness World Record with cast and filmmakers of Columbia Pictures' The Da Vinci Code" (Press release). Eurostar. 17 June 2006. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- "Eurostar breaks UK high speed record" (Press release). Eurostar. 30 July 2003.

- "Eurostar sets Paris-London record". BBC News. 4 September 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- Williams, Michael (21 September 2007). "Eurostar puts Brussels within the 'two-hour club' after record rail journey". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- "Review of regional Eurostar services: summary report". Department for Transport. n.d. Archived from the original on 14 December 2010.

- "Eurostar extension in doubt". BBC News. 28 April 1999. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- Knowles, Richard; Farrington, John (December 1998). "Why Has the Market Not Been Created for Channel Tunnel Regional Passenger Rail Services?". Area. Royal Geographical Society. 30 (4): 359–366. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.1998.tb00080.x. JSTOR 20003928.

- "High-speed GNER trains scrapped". BBC News. 16 January 2002. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- White Rose to run to Leeds with extra trains Rail issue 428 6 February 2002 page 16

- "Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL), United Kingdom". Railway-technology-com. n.d. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- SNCF prepares to use Eurostar sets Today's Railways UK issue 64 April 2007 page 68

- Guerra, Michael (December 2003). "Second chance for Eurostar sleepers" (PDF). Railwatch. No. 93. RailFuture. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- Middleton, William D. (August 2003). "Via Rail's renaissance: "Renaissance" is the name Via Rail Canada has given its new fleet of European-built passenger cars, but it applies equally well to the entire operation". Railway Age. New York. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- Hickling, Michael (1 November 2007). "Fast track to Europe – old track to Yorkshire". Yorkshire Post. Leeds.

- "Official Ashford International information page". Eurostar. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- "Save Ashford International". saveashfordinternational.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- "Ashford to become a 'ghost town'". Metro. 12 September 2006.

- Harrison, Michael (12 September 2006). "Eurostar cutbacks deliver blow to Ashford". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- "New station means Eurostar change". BBC News. 12 September 2006. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- "Petition opposing Eurostar cuts". BBC News. 3 April 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- "Town fears losing Eurostar trains". BBC News. 27 October 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- "Ashford International to Brussels". Eurostar. Archived from the original on 30 January 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- Hemsley, Andy. "Rye back on international rail map". Rye and Battle Observer. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- "Eurostar confirms plans for senior management changes". Breaking Travel News. 20 August 2009.

- "UK government sells Eurostar stake for £757.1m". BBC News Online. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

Patina Rail LLP will acquire the UK Treasury's entire share … consortium is made up of two companies: Canadian-based Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ) and the UK's Hermes Infrastructure … will own 30% and 10% of Eurostar respectively

- "Behind the scenes - Eurostar". Eurostar.com.

- "Hermes secures Eurostar ownership for pension funds after UK sell-off". Realestate.jpe.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- "House of Commons Hansard Ministerial Statements for 19 Jun 2014 (pt 0001)". UK Parliament. House of Commons. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "Eurostar rail stake touted for sale by UK government". BBC News. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Eurostar reverses bike storage decision". BBC News. 14 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Julian Glover (16 March 2016). "Bring your own device to Eurostar entertainment". Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "Green Speed: A project to combine Eurostar and Thalys has been presented to the boards of their shareholders to meet the demand for sustainable travel in Europe". Eurostar Media Centre (Press release). 27 September 2019. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- "Eurostar-Thalys merger proposal revealed". International Railway Journal. 27 September 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Posaner, Joshua (27 September 2019). "Eurostar, Thalys merger floated to create high-speed rail giant". Politico. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Eurostar and Thalys to merge in 2021 BusinessTraveller

- "Eurostar brand to remain after Thalys merger". Railway Gazette International. 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- "Eurostar brand to be retained in Thalys merger". International Railway Journal. 4 October 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- Rizzo, Cailey (19 January 2021). "Eurostar Rail Service Facing Financial Woes Due to COVID-19". Travel + Leisure.

- "Eurostar finances near collapse as Covid cuts cross-channel train traffic". RFI. 19 January 2021.

- Jasper, Christopher (17 January 2021). "Eurostar Survival Concern Grows as U.K. Firms Lobby for Rescue". Bloomberg.

- Wood, Zoe (17 January 2021). "Eurostar warns of 'risk to survival' without government help". Guardian.

- Twitter. 19 February 2021 https://twitter.com/EurostarJustinp/status/1495033418656239616. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Coronavirus: Eurostar trains will not stop in Kent until at least 2023". BBC News. 16 September 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- "TIMETABLES". Eurostar4Agents. 29 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- "Important information about trains to Disneyland® Paris - Summer 2023". Eurostar4Agents. 25 August 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- "Eurostar & Travelski 2022/23". Eurostar4Agents. 13 September 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- (in French)"Bilan LOTI de la LGV Nord Rapport" (PDF). Réseau Ferré de France. May 2005. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- O'Connell, Dominic (13 March 2008). "Fees for high-speed tunnel link derail Eurostar's gravy train". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- Reynolds, Christopher (19 May 1996). "Seven Wonders of the World: The Modern List". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio.

- "Eurostar article". railfaneurope.net. 27 May 2001. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- "Eurotunnel Network Statement 2008" (PDF). Eurotunnel. 18 March 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- Kirkland, C.J. (2002). "The fire in the Channel Tunnel" (PDF). Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology. 17 (2): 129–132. doi:10.1016/S0886-7798(02)00014-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2010.

- "Lorry fire closes Channel Tunnel". BBC News. 21 August 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- "Tunnel fire eats into Eurostar's passenger numbers". Kent Online. Maidstone. 16 April 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- "Belgische spoorlijnen". users.telenet.be.

- "Infrabel celebrates 10 years of the High Speed Line in Belgium" (Press release). Brussels: Infrabel. 14 December 2007. Archived from the original (DOC) on 3 March 2016.

- "Detailed map layout of Belgian railway transportation network" (PDF). Infrabel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- "New £7.5 million railway viaduct at Brussels Midi station further enhances Eurostar reliability on the London–Brussels route" (Press release). Eurostar. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "High Speed 1, United Kingdom". railway-technology.com. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- "The need for a Channel Tunnel Rail Link". Department for Transport. Archived from the original on 13 June 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- "Eurostar arrives in Paris on time". BBC News. 14 November 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- "With the new Eurostar high speed rail link, Alstom participates in the European rail network" (Press release). Alstom. 7 November 2007.

- Rudd, Matt (28 October 2007). "Eurostar to Brussels". The Times. London. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- "UK's HS1 becomes the country's first renewable-powered railway". ET Energy World. 21 October 2020.

- "Eurostar service from 16 December 2019 to 16 May 2020" (PDF). Eurostar. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- "Destinations". Eurostar. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- "Disneyland by Eurostar". Travel Empire. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "Eurostar confirms end of Disneyland service". Railway Gazette International. London. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- "Eurostar Snow Train". Eurostar. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "Eurostar winter ski tickets". thisfrenchlife.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- "Direct Eurostar from London to Amsterdam - Starts 4 April 2018 - Timetable, fares, tickets". www.seat61.com.