Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east and northeast, Kenya to the south, South Sudan to the west, and Sudan to the northwest. Ethiopia has a total area of 1,100,000 square kilometres (420,000 sq mi). As of 2022, it is home to around 113.5 million inhabitants, making it the 12th-most populous country in the world and the 2nd-most populous in Africa after Nigeria.[15][16][17] The national capital and largest city, Addis Ababa, lies several kilometres west of the East African Rift that splits the country into the African and Somali tectonic plates.[18]

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Name in national languages

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Flag

Emblem

| |||||||||||

| Anthem: ወደፊት ገስግሺ ፣ ውድ እናት ኢትዮጵያ (English: "March Forward, Dear Mother Ethiopia") | |||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) | |||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Addis Ababa 9°1′N 38°45′E | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Afar Amharic Oromo Somali Tigrinya[1][2][3] | ||||||||||

Regional languages[4] |

| ||||||||||

| Ethnic groups | |||||||||||

| Religion (2016[7]) |

| ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Ethiopian | ||||||||||

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic[8] | ||||||||||

• President | Sahle-Work Zewde | ||||||||||

• Prime Minister | Abiy Ahmed | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Federal Parliamentary Assembly | ||||||||||

| House of Federation | |||||||||||

| House of Peoples' Representatives | |||||||||||

| Formation | |||||||||||

• Ethiopian Empire | 1270 | ||||||||||

• Zemene Mesafint | 7 May 1769 | ||||||||||

• Reunification | 11 February 1855 | ||||||||||

| 1904 | |||||||||||

• Occupied and annexed into Italian East Africa | 9 May 1936 | ||||||||||

• Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement | 31 January 1942 | ||||||||||

• Derg | 12 September 1974 | ||||||||||

• Transitional government | 28 May 1991 | ||||||||||

• Current constitution | 21 August 1995 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

• Total | 1,104,300[9] km2 (426,400 sq mi) (26th) | ||||||||||

• Water (%) | 0.7 | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 2022 estimate | 113,656,596[10] (13th) | ||||||||||

• 2007 census | 73,750,932[6] | ||||||||||

• Density | 92.7/km2 (240.1/sq mi) (123rd) | ||||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate | ||||||||||

• Total | $345.14 billion[11] (56th) | ||||||||||

• Per capita | $3,407[12] | ||||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate | ||||||||||

• Total | $122.591 billion[12] (65th) | ||||||||||

• Per capita | $1,040[12] | ||||||||||

| Gini (2015) | medium | ||||||||||

| HDI (2019) | low · 173rd | ||||||||||

| Currency | Birr (ETB) | ||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) | ||||||||||

| Driving side | right | ||||||||||

| Calling code | +251 | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ET | ||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .et | ||||||||||

Anatomically modern humans emerged from modern-day Ethiopia and set out to the Near East and elsewhere in the Middle Paleolithic period.[19][20][21][22][23] Southwestern Ethiopia has been proposed as a possible homeland of the Afroasiatic language family.[24] In 980 BCE, the Kingdom of D'mt extended its realm over Eritrea and the northern region of Ethiopia, while the Kingdom of Aksum maintained a unified civilization in the region for 900 years. Christianity was embraced by the kingdom in 330,[25] and Islam arrived by the first Hijra in 615.[26] After the collapse of Aksum in 960, a variety of kingdoms, largely tribal confederations, existed in the land of Ethiopia. The Zagwe dynasty ruled the north-central parts until being overthrown by Yekuno Amlak in 1270, inaugurating the Ethiopian Empire and the Solomonic dynasty, claimed descent from the biblical Solomon and Queen of Sheba under their son Menelik I. By the 14th century, the empire grew in prestige through territorial expansion and fighting against adjacent territories; most notably, the Ethiopian–Adal War (1529–1543) contributed to fragmentation of the empire, which ultimately fell under a decentralization known as Zemene Mesafint in the mid-18th century. Emperor Tewodros II ended Zemene Mesafint at the beginning of his reign in 1855, marking the reunification and modernization of Ethiopia.[27]

From 1878 onwards, Emperor Menelik II launched a series of conquests known as Menelik's Expansions, which resulted in the formation of Ethiopia's current border. Externally, during the late 19th century, Ethiopia defended itself against foreign invasions, including from Egypt and Italy; as a result, Ethiopia and Liberia preserved their sovereignty during the Scramble for Africa. In 1935, Ethiopia was occupied by Fascist Italy and annexed with Italian-possessed Eritrea and Somaliland, later forming Italian East Africa. In 1941, during World War II, it was occupied by the British Army, and its full sovereignty was restored in 1944 after a period of military administration. The Derg, a Soviet-backed military junta, took power in 1974 after deposing Emperor Haile Selassie and the Solomonic dynasty, and ruled the country for nearly 17 years amidst the Ethiopian Civil War. Following the dissolution of the Derg in 1991, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) dominated the country with a new constitution and ethnic-based federalism. Since then, Ethiopia has suffered from prolonged and unsolved inter-ethnic clashes and political instability marked by democratic backsliding. From 2018, regional and ethnically based factions carried out armed attacks in multiple ongoing wars throughout Ethiopia.[28]

Ethiopia is a multi-ethnic state with over 80 different ethnic groups. Christianity is the most widely professed faith in the country, with significant minorities of the adherents of Islam and a small percentage to traditional faiths. This sovereign state is a founding member of the UN, the Group of 24, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Group of 77, and the Organisation of African Unity. Addis Ababa is the headquarters of the African Union, the Pan African Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the African Standby Force and many of the global non-governmental organizations focused on Africa. Ethiopia is considered an emerging power[29][30] and developing country, having the fastest economic growth in Sub-Saharan African countries because of foreign direct investment in expansion of agricultural and manufacturing industries.[31] However, in terms of per capita income and the Human Development Index,[32] the country is regarded as poor with high rates of poverty,[33] poor respect for human rights, and a literacy rate of only 49%.[34] Agriculture is the largest economic sector in Ethiopia, accounting for 36% of the country's gross domestic product as of 2020.[35][36]

Etymology

The Greek name Αἰθιοπία (from Αἰθίοψ, Aithiops, "an Ethiopian") is a compound word, derived from the two Greek words, from αἴθω + ὤψ (aithō "I burn" + ōps "face"). According to the Liddell-Scott Jones Greek-English Lexicon, the designation properly translates as burnt-face in noun form and red-brown in adjectival form.[37] The historian Herodotus used the appellation to denote those parts of Africa south of the Sahara that were then known within the Ecumene (habitable world).[38] Since the Greeks understood the term as "dark-faced", they divided the Ethiopians into two, those in Africa and those to the east from eastern Turkey to India.[39] This Greek name was borrowed into Amharic as ኢትዮጵያ, ʾĪtyōṗṗyā.

In Greco-Roman epigraphs, Aethiopia was a specific toponym for ancient Nubia.[40] At least as early as c. 850,[41] the name Aethiopia also occurs in many translations of the Old Testament in allusion to Nubia. The ancient Hebrew texts identify Nubia instead as Kush.[42] However, in the New Testament, the Greek term Aithiops does occur, referring to a servant of the Kandake, the queen of Kush.[43]

Following the Hellenic and biblical traditions, the Monumentum Adulitanum, a 3rd-century inscription belonging to the Aksumite Empire, indicates that Aksum's ruler governed an area which was flanked to the west by the territory of Ethiopia and Sasu. The Aksumite King Ezana eventually conquered Nubia the following century, and the Aksumites thereafter appropriated the designation "Ethiopians" for their own kingdom. In the Ge'ez version of the Ezana inscription, Aἰθίοπες is equated with the unvocalized Ḥbšt and Ḥbśt (Ḥabashat), and denotes for the first time the highland inhabitants of Aksum. This new demonym was subsequently rendered as ḥbs ('Aḥbāsh) in Sabaic and as Ḥabasha in Arabic.[40]

In the 15th-century Ge'ez Book of Axum, the name is ascribed to a legendary individual called Ityopp'is. He was an extra-biblical son of Cush, son of Ham, said to have founded the city of Axum.[44]

In English, and generally outside of Ethiopia, the country was historically known as Abyssinia. This toponym was derived from the Latinized form of the ancient Habash.[45]

History

Prehistory

Several important finds have propelled Ethiopia and the surrounding region to the forefront of palaeontology. The oldest hominid discovered to date in Ethiopia is the 4.2 million-year-old Ardipithicus ramidus (Ardi) found by Tim D. White in 1994.[46] The most well-known hominid discovery is Australopithecus afarensis (Lucy). Known locally as Dinkinesh, the specimen was found in the Awash Valley of Afar Region in 1974 by Donald Johanson, and is one of the most complete and best preserved adult Australopithecine fossils ever uncovered. Lucy's taxonomic name refers to the region where the discovery was made. This hominid is estimated to have lived 3.2 million years ago.[47][48][49]

Ethiopia is also considered one of the earliest sites of the emergence of anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens. The oldest of these local fossil finds, the Omo remains, were excavated in the southwestern Omo Kibish area and have been dated to the Middle Paleolithic, around 200,000 years ago.[50] Additionally, skeletons of Homo sapiens idaltu were found at a site in the Middle Awash valley. Dated to approximately 160,000 years ago, they may represent an extinct subspecies of Homo sapiens, or the immediate ancestors of anatomically modern humans.[51] Archaic Homo sapiens fossils excavated at the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco have since been dated to an earlier period, about 300,000 years ago,[52] while Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) from southern Ethiopia is the oldest anatomically modern Homo sapiens skeleton currently known (196 ± 5 ka).[53]

According to some linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic era from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[54] or the Near East.[55] The majority of scholars today propose that the Afroasiatic family developed in northeast Africa because of the higher diversity of lineages in that region, a telltale sign of linguistic origin.[56][57][58]

In 2019, archaeologists discovered a 30,000-year-old Middle Stone Age rock shelter at the Fincha Habera site in Bale Mountains at an elevation of 3,469 metres above sea level. At this high altitude humans are susceptible both to hypoxia and to extreme weather. According to a study published in the journal Science, this dwelling is proof of the earliest permanent human occupation at high altitude yet discovered. Thousands of animal bones, hundreds of stone tools, and ancient fireplaces were discovered, revealing a diet that featured giant mole rats.[59][60][61][62][63][64][65]

Evidence of some of the earliest known stone-tipped projectile weapons (a characteristic tool of Homo sapiens), the stone tips of javelins or throwing spears, were discovered in 2013 at the Ethiopian site of Gademotta, which date to around 279,000 years ago.[66] In 2019, additional Middle Stone Age projectile weapons were found at Aduma, dated 100,000–80,000 years ago, in the form of points considered likely to belong to darts delivered by spear throwers.[67]

Antiquity

In 980 BCE, Dʿmt was established in present-day Eritrea and the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. This polity's capital was located at Yeha in what is now northern Ethiopia. Most modern historians consider this civilization to be a native Ethiopian one, although in earlier times many suggested it was Sabaean-influenced because of the latter's hegemony of the Red Sea.[68]

Other scholars regard Dʿmt as the result of a union of Afroasiatic-speaking cultures of the Cushitic and Semitic branches; namely, local Agaw peoples and Sabaeans from Southern Arabia. However, Ge'ez, the ancient Semitic language of Ethiopia, is thought to have developed independently from the Sabaean language. As early as 2000 BCE, other Semitic speakers were living in Ethiopia and Eritrea where Ge'ez developed.[69][70] Sabaean influence is now thought to have been minor, limited to a few localities, and disappearing after a few decades or a century. It may have been a trading or military colony in alliance with the Ethiopian civilization of Dʿmt or some other proto-Axumite state.[68]

After the fall of Dʿmt during the 4th century BCE, the Ethiopian plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms. In the 1st century CE, the Kingdom of Aksum emerged in what is now Tigray Region and Eritrea. According to the medieval Book of Axum, the kingdom's first capital, Mazaber, was built by Itiyopis, son of Cush.[44] Aksum would later at times extend its rule into Yemen on the other side of the Red Sea.[71] The Persian prophet Mani listed Axum with Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of his era, during the 3rd century.[72] It is also believed that there was a connection between Egyptian and Ethiopian churches. There is diminutive evidence that the Aksumites were associated with the Queen of Sheba, via their royal inscription.[73]

Around 316 CE, Frumentius and his brother Edesius from Tyre accompanied their uncle on a voyage to Ethiopia. When the vessel stopped at a Red Sea port, the natives killed all the travellers except the two brothers, who were taken to the court as slaves. They were given positions of trust by the monarch, and they converted members of the royal court to Christianity. Frumentius became the first bishop of Aksum.[74] A coin dated to 324 shows that Ethiopia was the second country to officially adopt Christianity (after Armenia did so in 301), although the religion may have been at first confined to court circles; it was the first major power to do so. The Aksumites were accustomed to the Greco-Roman sphere of influence, but embarked on significant cultural ties and trade connections between the Indian subcontinent and the Roman Empire via the Silk Road, primarily exporting ivory, tortoise shell, gold and emeralds, and importing silk and spices.[73][75][76]

Middle Ages

The kingdom adopted the name "Ethiopia" during the reign of Ezana in the 4th century. After the conquest of Kingdom of Kush in 330, the Aksumite territory reached its peak between the 5th and 6th centuries.[68] This period was interrupted by several incursions into the South Arabian protectorate, including Jewish Dhu Nuwas of the Himyarite Kingdom and the Aksumite–Persian wars. In 575, the Aksumites besieged and retook Sana'a following the assassination of its governor Sayf ibn Dhī Yazan. The port city of Adulis was plundered by Arab Muslims in the 8th century; along with irrevocable land degradation, claimed climate change and sporadic rainfall precipitation from 730 to 760,[77] the kingdom likely said to decline its power and important trade route, and Red Sea was left to the Rashidun Caliphate in 646.[68][78]

Aksum came to an end in 960 when Queen Gudit defeated the last king of Aksum. Gudit's reign, which lasted for 40 years, aimed to abolish Christianity (a religion first accepted by King Ezana of the Axumite dynasty) by burning down churches and crucifying people who remained faithful to the Orthodox Tewahedo Church, which at the time was considered as the religion of the state.[79] Gudit tried to force many people to change their religion and destroyed much historical heritage of the Axumite dynasty, earning her the epithet of Yodit Gudit (in Amharic: ዮዲት ጉዲት a play on words approximating to Judith the Evil One). Gudit's devastation caused the remnant of the Aksumite population to shift into the southern region and establish the Zagwe dynasty, changing its capital to Lalibela. The dynasty was ruled by ethnic Agaw from circa 912, although most native sources indicate 1137 when its founder Mara Takla Haymanot overthrew the last Aksumite king Dil Na'od and married his daughter. The Zagwe dynasty was known for the revival of Christianity, and by the 13th century Christianity reached the Shewan region.[80]

.jpg.webp)

Zagwe's rule ended when an Amhara noble man Yekuno Amlak revolted against King Yetbarak and established the Ethiopian Empire (known by exonym "Abyssinia"). He inaugurated the Solomonic dynasty that supposedly traced to the biblical Solomon and Queen of Sheba, a claim that Menelik I was their firstborn inaugurated the dynasty and the first Emperor of Ethiopia in the 10th century BCE. According to the medieval Ethiopian chronicle Kebra Nagast, which was translated to Ge'ez in 1321, his name was Bäynä Ləḥkəm (from Arabic: ابن الحكيم, Ibn Al-Hakim, "Son of the Wise"[81]).

In the early 15th century, Ethiopia sought to make diplomatic contact with European kingdoms for the first time since the Aksumite era. A letter from Henry IV of England to the Ethiopian emperor survives.[82] In 1428, Yeshaq I sent two emissaries to Alfonso V of Aragon, who sent his own emissaries that failed to complete the return trip home to Aragon.[83] The first continuous relations Europeans began in 1508 with Portugal under Dawit II.[84]

Abyssinian–Adal War (1529–1543)

The Ethiopian Empire embarked on territorial expansion starting with Amda Seyon I, who conquered the first Muslim state in the region, Ifat Sultanate, in the 14th century after seizing the Kingdom of Damot around 1317, and expansion efforts were sustained by Emperor Zara Yaqob who conquered Massawa and Dahlak Archipelago around 1465.[85][86][87] Ifat's successor, the Adal Sultanate, emerged in 1415 with its capital at Zelia, situated in the present-day Somaliland.[88]

The Adals, supported by Ottoman Turks, initially tried to encroach the Ethiopian Empire under Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi in 1529, launching the Ethiopian–Adal War. After several campaigns, Al-Ghazi overwhelmed the Ethiopian troops at the Battle of Amba Sel in 1531. Cristóvão da Gama played a prominent role in the war, helping the Ethiopian Empire with 400 musketeers at Massawa. His vital efforts eventually led to his death at Battle of Wofla in 1542. In 1543, the Abyssinian troops led by Emperor Gelawdewos decisively defeated the Adal forces at the Battle of Wayna Daga; the Imam was fatally wounded, where tradition states that Ahmad was wounded by a Portuguese musketeer who had charged alone into the Muslim lines and died. The wounded Imam was then chased and beheaded by an Ethiopian cavalry commander, named Azmach Calite. Upon learning of his death, the Adal troops immediately withdrew the area.[89]

Gelawdewos was beheaded at the Battle of Fatagar in 1559.[90][91] In response, Abyssinian Ras Hamalmal sacked the Adal capital of Harar and killed the Sultan Barakat ibn Umar Din.[92][93] These series of conflicts paved the way for 16th-century Oromo migrations to the northern highlands.[94]

Oromo migrations (16th century)

By the 16th century, an influx of migration by ethnic Oromo into northern parts of the region fragmented the empire's power, referred to as the "Great Oromo Expansions." Embarking from present-day Guji and Borena Zone, the Oromos were largely motivated by several folkloric conceptions—beginning with Moggaasaa[95] and Liqimssa[96]—many of whom related to their raids. Early expansion was marked by rapid raids, as the raiders captured most cattle and booty and then returned to their homeland. This technique persisted until gada of Meslé.[97][98] According to Abba Bahrey, the earliest expansion occurred under Emperor Dawit II (luba Melbah), when they encroached to Bale before invading Adal Sultanate.[99]

Emperor Sarsa Dengel unsuccessfully attempted to suppress the invasion in the south after they had taken Wej in 1572.[100]

Jesuit influence (1555–1632)

.jpg.webp)

Ethiopia saw major diplomatic contact with Portugal from the 17th century, mainly related to religion. Beginning in 1555,[101] the Portuguese Jesuits attempted to develop Roman Catholicism as the state religion. After several failures, they sent several missionaries in 1603, including the most influential Spanish Jesuit Pedro Paez. Paez's enthusiastic relation had huge favorable effects on the political sphere. The Jesuits, including Manoel de Almeida, Manoel Barradas, and Jerónimo Lobo, wrote a half dozen histories regarding the first interaction with Ethiopians. Their book, however, was unknown until the 20th century when it was fully published.[102] Under Emperor Susenyos I, Roman Catholicism became the state religion of the Ethiopian Empire in 1622.[103] This unprecedented decision immediately caused an uprising by the Orthodox populace.[104]

Gondarine period (1632–1769)

In 1632, Emperor Fasilides successfully halted Roman Catholic state administration and restored Orthodox Tewahedo as the state religion.[103] Fasilides' reign sparked solidification of imperial power and moved the capital to Gondar in 1636, commencing a period of transition known as "Gondarine period".[105] He expelled Jesuits by reclaiming possessed lands and relegating them to Fremona. During his reign, he built one of the most iconic royal fortress, Fasil Ghebbi, forty-four churches were built[106] and Ethiopian art was revived. He also credited with constructing seven stone bridges over Blue Nile River.[107]

Rebellion of the Agaw population in Lasta endured the reformation. Fasilides conducted punitive expeditions to Lasta and successfully suppress it, which was described by the Scottish traveler James Bruce, "almost the whole army perished amidst the mountains; great part from famine, but a greater still from cold, a very remarkable circumstance in these latitudes."[108] Fasilides tried to establish firm relations with Yemeni Imam Al-Mutawakkil Isma'il between 1642 and 1647 to discuss a trade route through Ottoman-held Massawa, which was unsuccessful.[109]

Gondar's power and reputation decayed following the death of Iyasu I in 1706 because most emperors preferred to enjoy luxurious life rather than spending in politics. After Iyasu II death in 1755, Empress Mentewab brought her brother, Ras Wolde Leul, to Gondar and made him Ras Bitwaded, resulted in regnal conflict between Mentewab's Quaregnoch and Wollo group led by Wubit. In 1767, Ras Mikael Sehul, a regent in Tigray Province, seized Gondar and murdered the child Iyoas I in 1769, who was emperor at the time, and installed 70-year-old Yohannes II, marking the beginning of the decentralized Zemene Mesafint era.[110]

Zemene Mesafint (1769–1889)

Between 1769 and 1855, Ethiopia experienced a period of isolation referred to as the Zemene Mesafint or "Age of Princes". The emperors became figureheads, controlled by regional lords and noblemen like Ras Mikael Sehul, Ras Wolde Selassie of Tigray, and by the Yejju Oromo dynasty of the Wara Sheh, such as Ras Gugsa of Yejju. Prior to the Zemene Mesafint, Emperor Iyoas I had introduced the Oromo language (Afaan Oromo) at court, instead of Amharic.[111][112]

Ethiopian isolationism ended following a British mission that concluded with an alliance between the two nations, but it was not until 1855 that the Amhara kingdoms of northern Ethiopia (Gondar, Gojjam, and Shewa) were briefly united after the power of the emperor was restored beginning with the reign of Tewodros II.[113][114] Tewodros II began a process of consolidation, centralisation, and state-building that would be continued by succeeding emperors. This process reduced the power of regional rulers, restructured the empire's administration, and created a professional army. These changes created the basis for establishing the effective sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Ethiopian state.[115]

Conversely, Tewodros suffered several rebellions inside his empire. Northern Oromo militias, Tigrayan rebellions, and the constant incursion of the Ottoman Empire and Egyptian forces near the Red Sea brought the weakening and the final downfall of Tewodros II. He killed himself in 1868 during his last fight with the British expedition to Abyssinia at the Battle of Magdala. After Tewodros' death, Tekle Giyorgis II was proclaimed emperor but was defeated in the Battles of Zulawu (21 June 1871) and Adwa (11 July 1871).

The victorious Mercha Kassai was subsequently declared Yohannes IV on 21 January 1872. In 1875 and 1876, Ottoman/Egyptian forces, accompanied by many European and American 'advisors', twice invaded Abyssinia but were initially defeated: once at the Battle of Gundit losing 800 men, and then in the second invasion, they were decisively defeated at the Battle of Gura on 7 March 1875, where the invading forces lost at least 3,000 men by death or capture.[116]

At the council of Boru Meda in 1878, Yohannes came out with a decree that Ethiopian Muslims must accept Christianity or be banned. Those that refused were executed on the spot. Tens of thousands were killed and more left their land and belongings to flee to Harar, Bale, Arsi, Jimma, and even to Sudan.[117] From 1885 to 1889, Ethiopia joined the Mahdist War allied to Britain, Turkey, and Egypt against the Sudanese Mahdist State. In 1887, Menelik II, king of Shewa, invaded the Emirate of Harar after his victory at the Battle of Chelenqo.[118] On 10 March 1889, Yohannes IV was killed by the Sudanese Khalifah Abdullah's army whilst leading his army in the Battle of Gallabat.[119]

From Menelik II to Adwa (1889–1913)

Ethiopia in roughly its current form began under the reign of Menelik II, who was Emperor from 1889 until his death in 1913. From his base in the central province of Shewa, Menelik set out to annex territories to the south, east, and west[120] — areas inhabited by the Oromo, Sidama, Gurage, Welayta, and other peoples.[121] He achieved this with the help of Ras Gobana Dacche's Shewan Oromo militia, which occupied lands that had not been held since Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi's war, as well as other areas that had never been under Ethiopian rule.[122] During the conquest of the Oromo, the Ethiopian Army carried out atrocities against the Oromo population including mass mutilation, mass killings, and large-scale slavery.[123][124] Some estimates of the number of people killed as a result of the conquest are in the millions.[125][123][126] Large-scale atrocities were also committed against the Dizi people and the people of the Kingdom of Kaffa.[126][127] Menelik's campaign against Oromos outside his army was largely in retaliation for centuries of Oromo expansionism and the Zemene Mesafint, a period during which a succession of Oromo feudal rulers dominated the highlanders.[128] Chief among these was the Yejju dynasty, which included Aligaz of Yejju and his brother Ali I of Yejju. The latter founded the town of Debre Tabor, in the Amhara Region, which became the dynasty's capital.[129]

Menelik II was the son of Haile Melekot, Negus of Shewa, and Ejegayehu Lema Adeyamo, a palace servant.[130] He was born at Angolala in an Oromo area and lived his first twelve years with Shewan Oromos, with whom he thus had much in common.[131] During Menelik's reign, road construction, electricity, and education advanced, and a central taxation system was developed. The city of Finfinne was rebuilt and renamed Addis Ababa; in 1889-1891 it became the new capital of the Ethiopian Empire.

.jpg.webp)

For his leadership, despite opposition from more traditional elements of society, Menelik II was heralded as a national hero. He had signed the Treaty of Wuchale with Italy in May 1889, by which Italy would recognize Ethiopia's sovereignty so long as Italy could control an area north of Ethiopia (now part of modern Eritrea). In return, Italy was to provide Menelik with weapons and support him as emperor. The Italians used the time between the signing of the treaty and its ratification by the Italian government to expand their territorial claims. This First Italo–Ethiopian War culminated in the Battle of Adwa on 1 March 1896, in which Italy's colonial forces were defeated by the Ethiopians.[121][132] In 1896, the Treaty of Addis Ababa was signed, replacing the Treaty of Wuchale with conditions more favorable to Ethiopia.

About a third of the population died in the Great Ethiopian Famine (1888 to 1892).[133][134]

Haile Selassie I era (1916–1974)

The early 20th century was marked by the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie (Ras Tafari). Haile Selassie I was born to parents with ethnic links to three Afroasiatic-speaking populations of Ethiopia: the Oromo and Amhara, the country's two largest ethnic groups, as well as the Gurage. He came to power after Lij Iyasu was deposed, and undertook a nationwide modernization campaign from 1916 when he was made a Ras and Regent (Inderase) for the Empress Regnant Zewditu, and became the de facto ruler of the Ethiopian Empire. Following Zewditu's death, on 2 November 1930, he succeeded her as emperor.[135] In 1931, Haile Selassie endowed Ethiopia with its first-ever Constitution in emulation of Imperial Japan's 1890 Constitution, through which the Central Europe a model of unitary and homogenous ethnolinguistic nation-state was adopted for the Ethiopian Empire.[136]

Fascist Italy occupation (1936–1941)

The independence of Ethiopia was interrupted by the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, beginning when it was invaded by Fascist Italy in early October 1935, and by subsequent Italian rule of the country (1936–1941) after Italian victory in the war.[137] During this time, Haile Selassie exiled and appealed to the League of Nations in 1935, delivering an address that made him a worldwide figure, and the 1935 Time Man of the Year.[138] As the majority of the Ethiopian population lived in rural towns, Italy faced continued resistance and ambushes in urban centers throughout its rule over Ethiopia. Haile Selassie fled into exile in Fairfield House, Bath, England. Mussolini was able to proclaim Italian Ethiopia and the assumption of the imperial title by the Italian King Vittorio Emanuele III.[139]

In 1937, the Italian massacre of Yekatit 12 took place, in which between 1,400 and 30,000 civilians were killed and many others imprisoned.[140][141][142] This massacre was a reprisal for the attempted assassination of Rodolfo Graziani, the viceroy of Italian East Africa.[143] The Italians employed the use of asphyxiating chemical weapons in their Ethiopian invasion. The Italians regularly dropped bombs throughout Ethiopia that carried mustard gas and debilitated the Ethiopian forces. On the whole, the Italians dropped about 300 tons of mustard gas as well as thousands of other artillery. This use of chemical weapons amounted to egregious war crimes.[144]

The Italians made investments in Ethiopian infrastructure development during their rule over Ethiopia. They created the so-called "imperial road" between Addis Ababa and Massaua.[145] More than 900 km of railways were reconstructed, dams and hydroelectric plants were built, and many public and private companies were established. The Italian government abolished slavery, a practice that existed in the country for centuries.[146]

Following the entry of Italy into World War II, British Empire forces, together with the Arbegnoch (literally, "patriots", referring to armed resistance soldiers) liberated Ethiopia in the course of the East African Campaign in 1941. An Italian guerrilla warfare campaign continued until 1943. The country was placed under British military administration. This was followed by British recognition of Ethiopia's full sovereignty, without any special British privileges, when the Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement was signed in December 1944,[147] although some regions remained under British control for more years. Under the peace treaty of 1947, Italy recognized the sovereignty and independence of Ethiopia.

On 26 August 1942, Haile Selassie issued a proclamation that removed legal basis for slavery.[148] Ethiopia had between two and four million slaves in the early 20th century, out of a total population of about eleven million.[149]

Post-World War II (1941–1974)

In 1952, Haile Selassie orchestrated a federation with Eritrea. He dissolved this in 1962 and annexed Eritrea, resulting in the Eritrean War of Independence.

Haile Selassie was nearly deposed in the 1960 coup d'état in a conspiracy by the chiefly progressive opposition group led by brothers Germame and Mengistu Neway whilst Selassie was on a state visit to Brazil. On the evening of Tuesday, 13 December, a group deceived the Ministers of the Imperial Crown and important personages to enter the National Palace, taking them hostage.[150] Fighting began on the next day primarily between the Loyalist imperial army (Kebur Zebegna) and rebels led by General Tsege and Colonel Warqenah. At its start, Germame and his fellow combatants killed 15 of the hostages held in Genetta Leul Palace. Central of these were officials such as then Prime Minister Ras Abebe Aregai, Makonnen Habte-Wolde and Major General Mulugeta.[151]

Heavily subdued by the imperial army, General Tsege was killed in fighting, Colonel Warqenah committed suicide,[152] and the brothers Mengistu and Germame Neway was near Mojo on 24 December, who would soon executed by hanging at church square in Addis Ababa but Germame evaded by committing suicide.[153] The coup considered one of serious threat to Haile Selassie until 1974 Ethiopian Revolution. In 1963, Haile Selassie played a leading role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU).[154]

Opinion within Ethiopia turned against Haile Selassie owing to the worldwide 1973 oil crisis causing a sharp increase in gasoline prices starting on 13 February 1974. The high gasoline prices motivated taxi drivers and teachers to go on strike on 18 February 1974, and students and workers in Addis Ababa began demonstrating against the government on 20 February 1974.[155] There were resulting food shortages, uncertainty regarding the succession, border wars, and discontent in the middle class created through modernization.[156] The feudal oligarchical cabinet of Aklilu Habte-Wold was toppled, and a new government was formed with Endelkachew Makonnen serving as Prime Minister.[157]

The Derg era (1974–1991)

Haile Selassie's rule ended on 12 September 1974, when he was deposed by the Derg, a non-ideological committee made up of military and police officers led by Aman Andom.[158] After the execution of 60 former government and military officials including Aman in November 1974,[159] the new Provisional Military Administrative Council now led by General Tafari Benti abolished the monarchy in March 1975 and established Ethiopia as a Marxist-Leninist state with itself as the vanguard party in a provisional government.[160] The abolition of feudalism, increased literacy, nationalization, and sweeping land reform including the resettlement and villagization from the Ethiopian Highlands became priorities.[161]

After internal conflicts that resulted in the execution of chairman Tafari Benti and several of his supporters in February 1977, and the execution of vice-chairman Atnafu Abate in November 1977, Mengistu Halie Mariam gained undisputed leadership of the Derg.[162]

The Derg suffered several coups, uprisings, wide-scale drought, and a huge refugee problem. In 1977, Somalia, which had previously been receiving assistance and arms from the USSR, invaded Ethiopia in the Ogaden War, capturing part of the Ogaden region. Ethiopia recovered it after it began receiving massive military aid from the Soviet bloc countries of the USSR, Cuba, South Yemen, East Germany,[163] and North Korea. This included around 15,000 Cuban combat troops.[164][165]

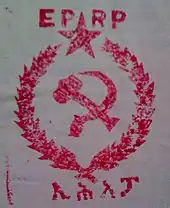

In 1976–78, up to 500,000 were killed as a result of the Red Terror,[166] a violent political repression campaign by the Derg against various opposition groups most notably the Marxist–Leninist Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP).[156] The Red Terror was carried out in response to what the Derg termed the 'White Terror', a chain of violent events, assassinations, and killings carried out by what it called "petty bourgeois reactionaries" who desired a reversal of the 1974 revolution.[167][168] In 1987, the Derg dissolved itself and established the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE) upon the adoption of the 1987 Constitution of Ethiopia modeled on the 1977 Constitution of the Soviet Union with modified provisions.[169]

The 1983–85 famine in Ethiopia affected around eight million people, resulting in one million dead. Insurrections against authoritarian rule sprang up, particularly in the northern regions of Eritrea and Tigray. The Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) merged with other ethnically based opposition movements in 1989, to form the coalition known as the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).[170]

Concurrently, under Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union began to retreat from building world communism towards glasnost and perestroika policies, marking a dramatic reduction in aid to Ethiopia from Socialist Bloc countries. This resulted in more economic hardship and the collapse of the military in the face of determined onslaughts by guerrilla forces in the north. The collapse of Marxism–Leninism in general, and in Eastern Europe during the revolutions of 1989, coincided with the Soviet Union stopping aid to Ethiopia altogether in 1990. To garner international support Mengistu embraced a mixed economy and an end to one party rule but it was too late to save his regime.[171][172][173]

EPRDF forces advanced on Addis Ababa in May 1991, and the Soviet Union did not intervene to save the government side. Mengistu fled the country and was granted asylum in Zimbabwe, where he still resides.[174][175]

In 2006, after a trial that lasted 12 years, Ethiopia's Federal High Court in Addis Ababa found Mengistu guilty of genocide in absentia.[176] Numerous other top leaders of his government were also found guilty of war crimes. Mengistu and others who had fled the country were tried and sentenced in absentia. Numerous former officials received the death sentence and tens of others spent the next 20 years in jail, before being pardoned from life sentences.[177][178][179][180]

Federal Democratic Republic (1991–present)

In July 1991, the EPRDF convened a National Conference to establish the Transitional Government of Ethiopia composed of an 87-member Council of Representatives and guided by a national charter that functioned as a transitional constitution.[181] In June 1992, the Oromo Liberation Front withdrew from the government; in March 1993, members of the Southern Ethiopia Peoples' Democratic Coalition also left the government.[182][183] In April 1993, Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia after a national referendum.[184] In 1994, a new constitution was written that established a parliamentary republic with a bicameral legislature and a judicial system.[185]

The first multiparty election took place in May 1995, which was won by the EPRDF.[186] The president of the transitional government, EPRDF leader Meles Zenawi, became the first Prime Minister of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, and Negasso Gidada was elected its president.[187] In post-Derg Ethiopia's Constitution (promulgated in 1995), the EPRDF not only took over the Derg's Soviet-inspired promise of cultural and administrative autonomy for the country's over 80 ethnic groups but also borrowed the right to independence (secession) from the Soviet Constitution. In this manner, an ethnoterritorial federal model of statehood was adopted for Ethiopia (as originally developed in the Central European empire of Austria-Hungary and in the interwar Soviet Union).[188]

In May 1998, a border dispute with Eritrea led to the Eritrean–Ethiopian War, which lasted until June 2000 and cost both countries an estimated $1 million a day.[189] This had a negative effect on Ethiopia's economy,[190] but strengthened the ruling coalition.

Ethiopia's 3rd multiparty election on 15 May 2005 was highly disputed, with many opposition groups claiming fraud. Though the Carter Center approved the pre-election conditions, it expressed its dissatisfaction with post-election events. European Union election observers cited state support for the EPRDF campaign, as well as irregularities in ballot counting and results publishing.[191] The opposition parties gained more than 200 parliamentary seats, compared with just 12 in the 2000 elections. While most of the opposition representatives joined the parliament, some leaders of the CUD party who refused to take up their parliamentary seats were accused of inciting the post-election violence and were imprisoned. Amnesty International considered them "prisoners of conscience" and they were subsequently released.[192]

A coalition of opposition parties and some individuals were established in 2009 to oust the government of the EPRDF in legislative elections of 2010. Meles' party, which has been in power since 1991, published its 65-page manifesto in Addis Ababa on 10 October 2009. The opposition won most votes in Addis Ababa, but the EPRDF halted the counting of votes for several days. After it ensued, it claimed the election, amidst charges of fraud and intimidation.[193]

In mid-2011, two consecutively missed rainy seasons precipitated the worst drought in East Africa seen in 60 years. Full recovery from the drought's effects did not occur until 2012, with long-term strategies by the national government in conjunction with development agencies believed to offer the most sustainable results.[194]

Meles died on 20 August 2012 in Brussels, where he was being treated for an unspecified illness.[195] Deputy Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn was appointed as a new prime minister until the 2015 elections,[196] and remained so afterwards with his party in control of every parliamentary seat.[197]

Protests broke out across the country on 5 August 2016 and hundreds of protesters were subsequently shot and killed by police. The protesters demanded an end to human rights abuses, the release of political prisoners, a fairer redistribution of the wealth generated by over a decade of economic growth, and a return of Wolqayt District to the Amhara Region.[198][199][200] The events were the most violent crackdown against protesters in Sub-Saharan Africa since the Ethiopian government killed at least 75 people during protests in the Oromia Region in November and December 2015.[201][202] Following these protests, Ethiopia declared a state of emergency on 6 October 2016.[203] The state of emergency was lifted in August 2017.[204]

On 16 February 2018, the government of Ethiopia declared a six-month nationwide state of emergency following the resignation of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn.[205] Hailemariam is the first ruler in modern Ethiopian history to step down; previous leaders have died in office or been overthrown.[206] He said that he wanted to clear the way for reforms.

Abiy Ahmed and the Prosperity Party (2018–present)

The new Prime Minister was Abiy Ahmed, who made an historic visit to Eritrea in 2018, ending the state of conflict between the two countries.[207] For his efforts in ending the 20-year-long war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, Abiy Ahmed was awarded the Nobel prize for peace in 2019.[208] After taking office in April 2018, 46-year-old Abiy released political prisoners, promised fair elections for 2019 and announced sweeping economic reforms.[209] As of 6 June 2019, all the previously censored websites were made accessible again, over 13,000 political prisoners were released and hundreds of administrative staff were fired as part of the reforms.[210][211][212][213]

Ethnic violence rose with the political unrest. There were Oromo–Somali clashes between the Oromo, who make up the largest ethnic group in the country, and the ethnic Somalis, leading to up to 400,000 have been displaced in 2017.[214] Gedeo–Oromo clashes between the Oromo and the Gedeo people in the south of the country led to Ethiopia having the largest number of people to flee their homes in the world in 2018, with 1.4 million newly displaced people.[215] Starting in 2019, in the Metekel conflict, fighting in the Metekel Zone of the Benishangul-Gumuz Region in Ethiopia has reportedly involved militias from the Gumuz people against Amharas and Agaws.[216] In March 2020, the leader of an Amhara militia called Fano, Solomon Atanaw, stated that they would not disarm until Metekel Zone and the Tigray Region districts of Welkait and Raya were returned to the control of Amhara Region.[217] In September 2018, 23 people were killed in acts of ethnic violence against minorities in the Special Zone of Oromia near the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa.[218] 35 people were later killed in Addis Ababa and in the surrounding Oromia Special Zone during protests against what many regarded as a lack of a response from the government to the violence. Some were killed by police.[219]

On 22 June 2019, factions of the security forces of the region attempted a coup d'état against the regional government, during which the President of the Amhara Region, Ambachew Mekonnen, was assassinated.[220] A bodyguard siding with the nationalist factions assassinated General Se'are Mekonnen – the Chief of the General Staff of the Ethiopian National Defense Force – as well as his aide, Major General Gizae Aberra.[220] The Prime Minister's Office accused Brigadier General Asaminew Tsige, head of the Amhara region security forces, of leading the plot,[221] and Tsige was shot dead by police near Bahir Dar on 24 June.[222]

.svg.png.webp)

(For a more detailed, up-to-date, interactive map, see here).

Pro-federal government troops

The Fano militia is an Amhara youth group in Ethiopia, perceived as either a protest group or an armed militia.[223] An alliance between Fano and Qeerroo, its Oromo counterpart, played a crucial role in the bringing about the political and administrative changes associated with the premiership of Abiy Ahmed.[224][225] During the Tigray War, Fano supported federal and regional security forces against rebels aligned with the Tigray People's Liberation Front or TPLF.[226] Fano units are accused of participating in ethnic massacres, including that of 58 Qemant people in Metemma during 10–11 January 2019,[227] and of armed actions in Humera in November 2020.[228]

Protests broke out across Ethiopia following the assassination of Oromo musician Hachalu Hundessa[229] on 29 June 2020, leading to the deaths of at least 239 people.[230]

The federal government, under the Prosperity Party, requested that the National Election Board of Ethiopia cancel elections for 2020 due to health and safety concerns about COVID-19. No official date was set for the next election at that time, but the government promised that once a vaccine was developed for COVID-19 that elections would move forward.[231] The Tigrayan ruling party, TPLF, opposed canceling the elections and, when their request to the federal government to hold elections was rejected, the TPLF proceeded to hold elections anyway on 9 September 2020. They worked with regional opposition parties and included international observers in the election process.[232] It was estimated that 2.7 million people participated in the election.[233]

Relations between the federal government and the Tigray regional government deteriorated after the election,[234] and on 4 November 2020, Abiy began a military offensive in the Tigray Region in response to attacks on army units stationed there, causing thousands of refugees to flee to neighbouring Sudan and triggering the Tigray War.[235][236] More than 600 civilians were killed in a massacre in the town of Mai Kadra on 9 November 2020.[237][238] In April 2021, Eritrea confirmed its troops are fighting in Ethiopia.[239] As of March 2022, as many as 500,000 people had died as a result of violence and famine in the Tigray War.[240][241] After a number of peace and mediation proposals in the intervening years, Ethiopia and the Tigrayan rebel forces agreed to a cessation of hostilities on 2 November 2022; as Eritrea was not a party to the agreement, however, their status remained unclear.[242]

Government and politics

Ethiopia is a federal parliamentary republic, wherein the Prime Minister is the head of government, and the President is the head of state but with largely ceremonial powers. Executive power is exercised by the government and federal legislative power vested in both the government and the two chambers of parliament. The House of Federation is the upper chamber of the bicameral legislature with 108 seats, and the lower chamber is the House of Peoples' Representatives (HoPR) with 547 seats. The House of Federation is chosen by the regional councils whereas MPs of the HoPR are elected directly, in turn, they elect the president for a six-year term and the prime minister for a 5-year term.

The Ethiopian judiciary consists of dual system with two court structures: the federal and state courts. The FDRE Constitution vested federal judicial authority to the Federal Supreme Court which can overturn and review decisions of subordinate federal courts; itself has regular division assigned for fundamental errors of law. In addition, the Supreme Court can perform circuit hearings in established five states at any states of federal levels or "area designated for its jurisdiction" if deemed "necessary for the efficient rendering of justice".[243][244]

The Federal Supreme Proclamation granted three subject matter principles: laws, parties and place to federal court jurisdiction, first "cases arising under the Constitution, federal laws and international treaties", second over "parties specified by federal laws".[245]

On the basis of Article 78 of the 1994 Ethiopian Constitution, the judiciary is completely independent of the executive and the legislature.[246] To ensure this, the vice-president and President of the Supreme Court appointed by Parliament on the nomination of Prime Minister. Once elected, the executive power has no authority to remove from office. Other judges are nominated by the Federal Judicial Administration Council (FJAC) on the basis of transparent criteria and the Prime Minister's recommendation for appointment in the HoPR. In all cases, judges cannot be removed from their duty unless they retired, violated disciplinary rules, gross incompatibility, or inefficiency to unfit due to ill health. Contrary, the majority vote of HoPR have the right to sanction removal in federal judiciary level or state council in cases of state judges.[247] In 2015, the realities of this provision were questioned in a report prepared by Freedom House.[248]

According to the Democracy Index published by the United Kingdom-based Economist Intelligence Unit in late 2010, Ethiopia was an "authoritarian regime", ranking as the 118th-most democratic out of 167 countries.[249] Ethiopia had dropped 12 places on the list since 2006, and the 2010 report attributed the drop to the government's crackdown on opposition activities, media, and civil society before the 2010 parliamentary election, which the report argued had made Ethiopia a de facto one-party state.

However, since the appointment of Abiy Ahmed as prime minister in 2018, the situation has rapidly evolved.

Governance

.jpeg.webp)

In post-1995 regime, Ethiopia's politics has been liberalized which promotes all-encompassing reforms to the country. Today, its economy is based on mixed, market-oriented.[247]

The first election of 547-member constituent assembly was held in June 1994. This assembly adopted the constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia in December 1994. The elections for Ethiopia's first popularly chosen national parliament and regional legislatures were held in May and June 1995. Most opposition parties chose to boycott these elections. There was a landslide victory for the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). International and non-governmental observers concluded that opposition parties would have been able to participate had they chosen to do so. The first government of Ethiopia under the new constitution was installed in August 1995 with Negasso Gidada as president. The EPRDF-led government of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi promoted a policy of ethnic federalism, devolving significant powers to regional, ethnically based authorities. Ethiopia today has eleven semi-autonomous administrative regions that have the power to raise and spend their own revenues. Under past governments, some fundamental freedoms, including freedom of the press, were circumscribed.[250]

Citizens had little access to media other than the state-owned networks, and most private newspapers struggled to remain open and suffered periodic harassment from the government.[250] Starting from the 2005 elections, at least 18 journalists who had written articles critical of the government, were arrested on genocide and treason charges. The government used press laws governing libel to intimidate journalists who were critical of its policies.[251]

Meles' government was elected in 2000 in the first-ever multiparty elections; however, the results were heavily criticized by international observers and denounced by the opposition as fraudulent. The EPRDF also won the 2005 election returning Meles to power. Although the opposition vote increased in the election, both the opposition and observers from the European Union and elsewhere stated that the vote did not meet international standards for fair and free elections.[250] Ethiopian police are said to have massacred 193 protesters, mostly in the capital Addis Ababa, in the violence following the May 2005 elections in the Ethiopian police massacre.[252]

.jpg.webp)

The government initiated a crackdown in the provinces as well; in Oromia Region, the authorities used concerns over insurgency and terrorism to use torture, imprisonment, and other repressive methods to silence critics following the election, particularly people sympathetic to the registered opposition party Oromo National Congress (ONC).[251] The government has been engaged in a conflict with rebels in the Ogaden region since 2007. The biggest opposition party in 2005 was the Coalition for Unity and Democracy (CUD). After various internal divisions, most of the CUD party leaders have established the new Unity for Democracy and Justice party led by Judge Birtukan Mideksa. A member of the country's Oromo ethnic group, Birtukan Mideksa is the first woman to lead a political party in Ethiopia.

In 2008, the top five opposition parties were the Unity for Democracy and Justice led by Judge Birtukan Mideksa, United Ethiopian Democratic Forces led by Beyene Petros, Oromo Federalist Democratic Movement led by Bulcha Demeksa, Oromo People's Congress led by Merera Gudina, and United Ethiopian Democratic Party – Medhin Party led by Lidetu Ayalew. After the 2015 elections, Ethiopia lost its single remaining opposition MP;[253] by 2015 there were no opposition MPs in the Ethiopian parliament.[254]

Foreign relations

.jpg.webp)

Starting from the Land of Punt, Ethiopia has been a trading nation that mainly exported goods such as gold, ivory, exotic animals, and incense.[255] Many historians concluded that modern diplomatic relationship of Ethiopia began under Emperor Tewodros II, whose reign was sought to establish Ethiopian border and later unsuccessfully diminished in British expedition of 1868.[256] Since then, the country was seen redundant by world powers until the opening of Suez Canal due to an influence of Mahdist War.[257]

Today, Ethiopia maintains strong relations with China, Israel, Mexico, Turkey and India as well as neighboring countries. The relationship with Sudan and Egypt is somewhat in dispute situation owing to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project, which was escalated in 2020.[258][259] Despite six upstream countries (Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania) signed Nile Basin Initiative in 2010, Egypt and Sudan rejected water sharing treaty citing the reduction of amount of water to the Nile Basin challenges their historic connection of water rights.[260][261] In 2020, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed warned that "No force can stop Ethiopia from building a dam. If there is need to go to war, we could get millions readied."[262] Ethiopia is a strategic partner of Global War on Terrorism and African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA).[263] US. Former President Barack Obama was the first incumbent to visit Ethiopia in July 2015, while delivering speech in the Africa Union, he highlighted combatting the Islamic terrorism.[264][265] Ethiopia has concentrated emigrant to countries in Europe mainly in Italy, Saudi Arabia, United Kingdom, Canada, Sweden and Australia. Ethiopia has Jewish emigrant in Israel about 155,300 as of 2019. They are collectively known as Beta Israel. Ethiopia is founding member of the Group of 24 (G-24), the Non-Aligned Movement and the G77. In 1963, the Organization of African Unity later renamed itself the African Union was founded in Addis Ababa serving the political center of the Union. In addition, it is also a member of the Pan African Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the African Standby Force and many of the global NGOs focused on Africa.

Ethiopia is one of African countries and founding member of League of Nations now United Nations since at least end of colonial era in 1923. The UN tasks in Ethiopia is primarily of humanitarian issues and development. For example, UN Country Team (UNCT) in Ethiopia has representative of 28 UN funds and programmes and specialized agencies. Some of its agencies mandate regional ligature with United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the African Union. The UN focuses all-encompassing affairs in Ethiopia, providing two goals: Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and National Development priority. This includes fighting against poverty, sustainable economic growth, climate change policy, educational and healthcare provision, increasing job employment and environmental protection.[266]

Military

.jpg.webp)

Historically, Ethiopia was heavily built on military and saw decisive invasions against external powers. Despite modern weapons equipped with assistance of European countries such as Portugal, Russia, France and Britain, the Ethiopian army largely relied on feudal system, so its army nearly consisted of peasant militia. Under Amda Seyon I, a legion named Chewa regiments was formed in the 14th century, became dominant military force in medieval times. It was normally composed up to several thousand men. The modern military dates back in 1917 created by Tafari Makonnen which was called Kebur Zabagna. The Ethiopian Army under Kagnew Battalion unit involved in the Korean War from 1950, fought as part of United Nations Command. Some publications stated that Ethiopian troops remained for 15 years, though other stated they left until 1975, as part of the UN Command.[267] The battalion sized 6,037 troops at the time of the war.[268]

The Ethiopian National Defense Force is the largest military in Africa[269] and is directed by Ministry of Defense. Other military branches include ground forces, air force and formerly naval force. Since 1996, landlocked Ethiopia has had no navy but in 2018 Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed said on state TV: "We built one of the strongest ground and air forces in Africa ... we should build our naval force capacity in the future."[270]

Law enforcement

The constitution guarantees law enforcement duty to the Ethiopian Federal Police (EFP). The EFP is responsible for safeguarding and public welfare in federal level. Founded in 1995, the federal police surveyed by Federal Police Commissioner since October 2000; the Federal Police Commissioner then reports task to the Ministry of Peace, however it was overrode after political reforms in 2018, and directed to the parliament. In previous years, the federal police reports the Ministry's tasks directly. In addition, the federal police have ability to disclose regional police commissions, in order for assistance. Independently, the local militias uphold security.

Nowadays, bribery is a basic concern, especially observed by traffic police. Police brutality appeared as severe in recent years. On 26 August 2019, a video of handcuffed man beaten by two police officers as an elderly woman intervened the scene in Addis Ababa went viral. Recent police misconduct is said to be a failure of Federal Police Commissioner to abide Article 52 of the constitution, which states investigation of unlawful use of force, and dismissal of those misconducted officer. The African Union's Luanda and Robben Island Guidelines or the United Nations' Declaration on Justice for Victims of Abuse of Power and their Basic Principles on the Use of Force & Firearms are once obligated to the Ethiopian government disciplinary committee to combat police brutality in both individual and systemic level.[271]

Human rights

Human rights violations often accompany endured ethnic and communal violence in the country.[272] In a 2016 demonstration, 100 peaceful protestors were killed by direct government gunfire in the Oromia and Amhara regions.[273] The UN has called for UN observers on the ground in Ethiopia to investigate this incident,[274] however the EPRDF-dominated Ethiopian government has refused this call.[275] The protestors are protesting land grabs and lack of basic human rights such as the freedom to elect their representatives. The TPLF-dominated EPRDF won 100% in an election marked by fraud which has resulted in Ethiopian civilians protesting on scale unseen in prior post-election protests.[276]

Merera Gudina, leader of the Oromo People's Congress, said the East African country was at a "crossroads". He added in the interview with Reuters: "People are demanding their rights", he said. "People are fed up with what the regime has been doing for a quarter of a century. They're protesting against land grabs, reparations, stolen elections, the rising cost of living, many things. "If the government continue to repress while the people are demanding their rights in the millions that (civil war) is one of the likely scenarios."[276]

According to surveys in 2003 by the National Committee on Traditional Practices in Ethiopia, marriage by abduction accounts for 69% of the nation's marriages, with around 80% in the largest region, Oromia, and as high as 92% in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region.[277][278] Journalists and activists have been threatened or arrested for their coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ethiopia.[279]

Among the Omotic Karo-speaking and Hamer peoples in southern Ethiopia, adults and children with physical abnormalities are considered to be mingi, "ritually impure". The latter are believed to exert an evil influence upon others; disabled infants have traditionally been murdered without a proper burial.[280] The Karo officially banned the practice in July 2012.[281]

In 2013, the Oakland Institute released a report accusing the Ethiopian government of forcing the relocation of "hundreds of thousands of indigenous people from their lands" in the Gambela Region.[282] According to several reports by the organization, those who refused were the subject of a variety of intimidation techniques including physical and sexual abuse, which sometimes led to deaths.[283][284][285] A similar 2012 report by Human Rights Watch also describes the Ethiopian government's 2010–2011 villagization program in Gambela, with plans to carry out similar resettlements in other regions.[286] The Ethiopian government has denied the accusations of land grabbing and instead pointed to the positive trajectory of the country's economy as evidence of the development program's benefits.[285] A nationwide series of violent protests, concentrated in the Oromia Region, broke out starting on 23 October 2019, sparked by activist and media owner Jawar Mohammed's allegation that security forces had attempted to detain him. According to official reports, 86 people were killed.[287] On 29 May 2020, Amnesty International released a report accusing the security forces of Ethiopia of mass detentions and extrajudicial killings. The report stated that in 2019, at least 25 people, suspected of supporting the Oromo Liberation Army, were killed by the forces in parts the Oromia Region. Besides, between January and September 2019, at least 10,000 people were detained under suspicion, where most were "subjected to brutal beatings".[288]

LGBT rights

Homosexual acts are illegal in Ethiopia. According to Criminal Code Article 629, same-sex activity is punished up to 15 years to life in prison.[289] Ethiopia has been a socially conservative country. The majority of people are hostile towards LGBT people and persecution is commonplace on the grounds of religious and societal norms. Homosexuality came to light in the country since the failed 2008 appeal to the Council of Ministers, and the LGBT scene began to thrive slightly in major metropolitan locations, such as Addis Ababa. Some notable hotels like Sheraton Addis and Hilton Hotel became hotbeds of accusations for alleged lobbying.[290]

The Ethiopian Orthodox church plays a frontal role in opposition; some of its members formed anti-gay organizations. For example, Dereje Negash, one prominent activist, founded "Zim Anlem" in 2014, which is a traditionalism and anti-gender movement.[291] According to the 2007 Pew Global Attitudes Project, 97 percent[292] of Ethiopians believe homosexuality is a way of life that society should not accept. This was the second-highest rate of non-acceptance in the 45 countries surveyed.[293]

Administrative divisions

Before 1996, Ethiopia was divided into thirteen provinces, many derived from historical regions. The nation now has a tiered governmental system consisting of a federal government overseeing regional states, zones, districts (woreda), and kebeles ("neighbourhoods").

Ethiopia is divided into eleven ethnically based and politically autonomous regional states (kililoch, singular kilil ) and two chartered cities (astedader akababiwoch, singular astedader akababi ), the latter being Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa. The kililoch are subdivided into sixty-eight zones, and then further into 550 woredas and several special woredas.

The constitution assigns extensive power to regional states, which can establish their own government and democracy as long as it is in line with the federal government's constitution. Each region has at its apex a regional council where members are directly elected to represent the districts and the council has legislative and executive power to direct internal affairs of the regions.

Furthermore, Article 39 of the Ethiopian Constitution gives every regional state the right to secede from Ethiopia. There is debate, however, as to how much of the power guaranteed in the constitution is actually given to the states. The councils implement their mandate through an executive committee and regional sectoral bureaus. Such an elaborate structure of council, executive and sectoral public institutions is replicated at the next level (woreda).

Geography

At 1,104,300 square kilometres (426,372.61 sq mi),[9] Ethiopia is the world's 28th-largest country, comparable in size to Bolivia. It lies between the 3rd parallel north and the 15th parallel north and longitudes 33rd meridian east and 48th meridian east.

The major portion of Ethiopia lies in the Horn of Africa, which is the easternmost part of the African landmass. The territories that have frontiers with Ethiopia are Eritrea to the north and then, moving in a clockwise direction, Djibouti, Somaliland, Somalia, Kenya, South Sudan and Sudan. Within Ethiopia is a vast highland complex of mountains and dissected plateaus divided by the Great Rift Valley, which runs generally southwest to northeast and is surrounded by lowlands, steppes, or semi-desert. There is a great diversity of terrain with wide variations in climate, soils, natural vegetation and settlement patterns.

Ethiopia is an ecologically diverse country, ranging from the deserts along the eastern border to the tropical forests in the south to extensive Afromontane in the northern and southwestern parts. Lake Tana in the north is the source of the Blue Nile. It also has many endemic species, notably the gelada, the walia ibex and the Ethiopian wolf ("Simien fox"). The wide range of altitude has given the country a variety of ecologically distinct areas, and this has helped to encourage the evolution of endemic species in ecological isolation.

The nation is a land of geographical contrasts, ranging from the vast fertile west, with its forests and numerous rivers, to the world's hottest settlement of Dallol in its north. The Ethiopian Highlands are the largest continuous mountain ranges in Africa, and the Sof Omar Caves contains the largest cave on the continent. Ethiopia also has the second-largest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Africa.[294]

Climate

The predominant climate type is tropical monsoon, with wide topographic-induced variation. The Ethiopian Highlands cover most of the country and have a climate which is generally considerably cooler than other regions at similar proximity to the Equator. Most of the country's major cities are located at elevations of around 2,000–2,500 m (6,562–8,202 ft) above sea level, including historic capitals such as Gondar and Axum.

The modern capital, Addis Ababa, is situated on the foothills of Mount Entoto at an elevation of around 2,400 metres (7,900 ft). It experiences a mild climate year round. With temperatures fairly uniform year round, the seasons in Addis Ababa are largely defined by rainfall: a dry season from October to February, a light rainy season from March to May, and a heavy rainy season from June to September. The average annual rainfall is approximately 1,200 millimetres (47 in).

There are on average seven hours of sunshine per day. The dry season is the sunniest time of the year, though even at the height of the rainy season in July and August there are still usually several hours per day of bright sunshine. The average annual temperature in Addis Ababa is 16 °C (60.8 °F), with daily maximum temperatures averaging 20–25 °C (68.0–77.0 °F) throughout the year, and overnight lows averaging 5–10 °C (41.0–50.0 °F).

Most major cities and tourist sites in Ethiopia lie at a similar elevation to Addis Ababa and have a comparable climate. In less elevated regions, particularly the lower lying Ethiopian xeric grasslands and shrublands in the east of Ethiopia, the climate can be significantly hotter and drier. Dallol, in the Danakil Depression in this eastern zone, has the world's highest average annual temperature of 34 °C (93.2 °F).

Ethiopia is vulnerable to many of the effects of climate change. These include increases in temperature and changes in precipitation. Climate change in these forms threatens food security and the economy, which is agriculture based.[295] Many Ethiopians have been forced to leave their homes and travel as far as the Gulf, Southern Africa and Europe.[296]

Since April 2019, the Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has promoted Beautifying Sheger, a development project that aims to reduce the negative effects of climate change – among other things – in the capital city Addis Ababa.[297] In the following May, the government held "Dine for Sheger", a fundraising event in order to cover some of the $1 billion needed through the public.[298] $25 million was raised through the expensive event, both through the cost of attending and donations.[299] Two Chinese railway companies under the Belt and Road Initiative between China and Ethiopia had supplied funds to develop 12 of the total 56 kilometres.[300]

Biodiversity

%252C_Bale%252CEthiopia_(14496349688).jpg.webp)

Ethiopia has 31 endemic species of mammals.[301] The African wild dog prehistorically had widespread distribution in the territory. However, with last sightings at Finicha'a, this canid is thought to be potentially locally extinct. The Ethiopian wolf is perhaps the most researched of all the endangered species within Ethiopia.

Ethiopia is a global centre of avian diversity. To date more than 856 bird species have been recorded in Ethiopia, twenty of which are endemic to the country.[302] Sixteen species are endangered or critically endangered. Many of these birds feed on butterflies, like the Bicyclus anynana.[303]

Historically, throughout the African continent, wildlife populations have been rapidly declining due to logging, civil wars, pollution, poaching, and other human factors.[304] A 17-year-long civil war, along with severe drought, negatively affected Ethiopia's environmental conditions, leading to even greater habitat degradation.[305] Habitat destruction is a factor that leads to endangerment. When changes to a habitat occur rapidly, animals do not have time to adjust. Human impact threatens many species, with greater threats expected as a result of climate change induced by greenhouse gases.[306] With carbon dioxide emissions in 2010 of 6,494,000 tonnes, Ethiopia contributes just 0.02% to the annual human-caused release of greenhouse gases.[307]

Ethiopia has many species listed as critically endangered and vulnerable to global extinction. The threatened species in Ethiopia can be broken down into three categories (based on IUCN ratings): critically endangered, endangered, and vulnerable.[301]

Ethiopia is one of the eight fundamental and independent centres of origin for cultivated plants in the world.[308] However, deforestation is a major concern for Ethiopia as studies suggest loss of forest contributes to soil erosion, loss of nutrients in the soil, loss of animal habitats, and reduction in biodiversity. At the beginning of the 20th century, around 420,000 km2 (or 35%) of Ethiopia's land was covered by trees, but recent research indicates that forest cover is now approximately 11.9% of the area.[309] The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.16/10, ranking it 50th globally out of 172 countries.[310]

Ethiopia loses an estimated 1,410 km2 of natural forests each year due to firewood collection, conversion to farmland, overgrazing, and use of forest wood for building material. Between 1990 and 2005 the country lost approximately 21,000 km2 of forests.[311] Current government programs to control deforestation consist of education, promoting reforestation programs, and providing raw materials which are alternatives to timber. In rural areas the government also provides non-timber fuel sources and access to non-forested land to promote agriculture without destroying forest habitat.[312]

Organizations such as SOS and Farm Africa are working with the federal government and local governments to create a system of forest management.[313] Working with a grant of approximately 2.3 million Euros, the Ethiopian government recently began training people on reducing erosion and using proper irrigation techniques that do not contribute to deforestation. This project is assisting more than 80 communities.

Economy

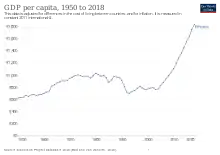

.svg.png.webp)

Ethiopia registered the fastest economic growth under Meles Zenawi's administration.[314] According to the IMF, Ethiopia was one of the fastest growing economies in the world, registering over 10% economic growth from 2004 through 2009.[315] It was the fastest-growing non-oil-dependent African economy in the years 2007 and 2008.[316] In 2015, the World Bank highlighted that Ethiopia had witnessed rapid economic growth with real domestic product (GDP) growth averaging 10.9% between 2004 and 2014.[317]

In 2008 and 2011, Ethiopia's growth performance and considerable development gains were challenged by high inflation and a difficult balance of payments situation. Inflation surged to 40% in August 2011 because of loose monetary policy, large civil service wage increase in early 2011, and high food prices.[318] For 2011–12, end-year inflation was projected to be about 22%, and single digit inflation is projected in 2012–13 with the implementation of tight monetary and fiscal policies.[319]

In spite of fast growth in recent years, GDP per capita is one of the lowest in the world, and the economy faces a number of serious structural problems. However, with a focused investment in public infrastructure and industrial parks, Ethiopia's economy is addressing its structural problems to become a hub for light manufacturing in Africa.[320] In 2019 a law was passed allowing expatriate Ethiopians to invest in Ethiopia's financial service industry.[321]

The Ethiopian constitution specifies that rights to own land belong only to "the state and the people", but citizens may lease land for up to 99 years, but are unable to mortgage or sell. Renting out land for a maximum of twenty years is allowed and this is expected to ensure that land goes to the most productive user. Land distribution and administration is considered an area where corruption is institutionalized, and facilitation payments as well as bribes are often demanded when dealing with land-related issues.[322] As there is no land ownership, infrastructural projects are most often simply done without asking the land users, which then end up being displaced and without a home or land. A lot of anger and distrust sometimes results in public protests. In addition, agricultural productivity remains low, and frequent droughts still beset the country, also leading to internal displacement.[323]

Energy and hydropower

Ethiopia has 14 major rivers flowing from its highlands, including the Nile. It has the largest water reserves in Africa. As of 2012, hydroelectric plants represented around 88.2% of the total installed electricity generating capacity.

The remaining electrical power was generated from fossil fuels (8.3%) and renewable sources (3.6%).