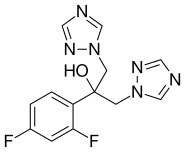

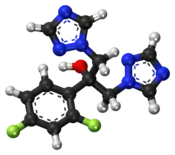

Fluconazole

Fluconazole is an antifungal medication used for a number of fungal infections.[3] This includes candidiasis, blastomycosis, coccidiodomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, dermatophytosis, and pityriasis versicolor.[3] It is also used to prevent candidiasis in those who are at high risk such as following organ transplantation, low birth weight babies, and those with low blood neutrophil counts.[3] It is given either by mouth or by injection into a vein.[3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Diflucan, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a690002 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >90% (oral) |

| Protein binding | 11–12% |

| Metabolism | liver 11% |

| Elimination half-life | 30 hours (range 20–50 hours) |

| Excretion | kidney 61–88% |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.156.133 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H12F2N6O |

| Molar mass | 306.277 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 139[2] °C (282 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include vomiting, diarrhea, rash, and increased liver enzymes.[3] Serious side effects may include liver problems, QT prolongation, and seizures.[3] During pregnancy it may increase the risk of miscarriage while large doses may cause birth defects.[4][3] Fluconazole is in the azole antifungal family of medication.[3] It is believed to work by affecting the fungal cellular membrane.[3]

Fluconazole was patented in 1981 and came into commercial use in 1988.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6] Fluconazole is available as a generic medication.[3] In 2019, it was the 133rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 5 million prescriptions.[7][8]

Medical uses

Fluconazole is a first-generation triazole antifungal medication. It differs from earlier azole antifungals (such as ketoconazole) in that its structure contains a triazole ring instead of an imidazole ring. While the imidazole antifungals are mainly used topically, fluconazole and certain other triazole antifungals are preferred when systemic treatment is required because of their improved safety and predictable absorption when administered orally.[9]

Fluconazole's spectrum of activity includes most Candida species (but not Candida krusei or Candida glabrata), Cryptococcus neoformans, some dimorphic fungi, and dermatophytes, among others. Common uses include:[9][10][11][12][13]

- The treatment of non-systemic Candida infections of the vagina ("yeast infections"), throat, and mouth.

- Certain systemic Candida infections in people with healthy immune systems, including infections of the bloodstream, kidney, or joints. Other antifungals are usually preferred when the infection is in the heart or central nervous system, and for the treatment of active infections in people with weak immune systems.

- The prevention of Candida infections in people with weak immune systems, such as those neutropenic due to cancer chemotherapy, those with advanced HIV infections, transplant patients, and premature infants.

- As a second-line agent for the treatment of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis, a fungal infection of the central nervous system.

Resistance

Fungal resistance to drugs in the azole class tends to occur gradually over the course of prolonged drug therapy, resulting in clinical failure in immunocompromised patients (e.g., patients with advanced HIV receiving treatment for thrush or esophageal Candida infection).[14]

In C. albicans, resistance occurs by way of mutations in the ERG11 gene, which codes for 14α-demethylase. These mutations prevent the azole drug from binding, while still allowing binding of the enzyme's natural substrate, lanosterol. Development of resistance to one azole in this way will confer resistance to all drugs in the class. Another resistance mechanism employed by both C. albicans and C. glabrata is increasing the rate of efflux of the azole drug from the cell, by both ATP-binding cassette and major facilitator superfamily transporters. Other gene mutations are also known to contribute to development of resistance.[14] C. glabrata develops resistance by up regulating CDR genes, and resistance in C. krusei is mediated by reduced sensitivity of the target enzyme to inhibition by the agent.[15]

The full spectrum of fungal susceptibility and resistance to fluconazole can be found in the TOKU-E's product data sheet.[16] According to the United States Centers for Disease Control, fluconazole resistance among Candida strains in the U.S. is about 7%.[17]

Contraindications

Fluconazole is contraindicated in patients who:[13]

- Drink alcohol

- have known hypersensitivity to other azole medicines such as ketoconazole;

- are taking terfenadine, if 400 mg per day multidose of fluconazole is administered;

- concomitant administration of fluconazole and quinidine, especially when fluconazole is administered in high dosages;

- take SSRIs such as fluoxetine or sertraline.

Side effects

Adverse drug reactions associated with fluconazole therapy include:[13]

- Common (≥1% of patients): rash, headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and/or elevated liver enzymes

- Infrequent (0.1–1% of patients): anorexia, fatigue, constipation

- Rare (<0.1% of patients): oliguria, hypokalaemia, paraesthesia, seizures, alopecia, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, thrombocytopenia, other blood dyscrasias, serious hepatotoxicity including liver failure, anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reactions

- Very rare: prolonged QT interval, torsades de pointes

- FDA is now saying treatment with chronic, high doses of fluconazole during the first trimester of pregnancy may be associated with a rare and distinct set of birth defects in infants.[18]

If taken during pregnancy it may result in harm.[19][20] These cases of harm, however, were only in women who took large doses for most of the first trimester.[19]

Fluconazole is secreted in human milk at concentrations similar to plasma. Therefore, the use of fluconazole in lactating mothers is not recommended.[21]

Fluconazole therapy has been associated with QT interval prolongation, which may lead to serious cardiac arrhythmias. Thus, it is used with caution in patients with risk factors for prolonged QT interval, such as electrolyte imbalance or use of other drugs that may prolong the QT interval (particularly cisapride and pimozide).[22]

Fluconazole has also rarely been associated with severe or lethal hepatotoxicity, so liver function tests are usually performed regularly during prolonged fluconazole therapy. In addition, it is used with caution in patients with pre-existing liver disease.[23]

Some people are allergic to azoles, so those allergic to other azole drugs might be allergic to fluconazole.[24] That is, some azole drugs have adverse side-effects. Some azole drugs may disrupt estrogen production in pregnancy, affecting pregnancy outcome. [25]

Fluconazole taken at low doses is in FDA pregnancy category C. However, high doses have been associated with a rare and distinct set of birth defects in infants. If taken at these doses, the pregnancy category is changed from category C to category D. Pregnancy category D means there is positive evidence of human fetal risk based on human data. In some cases, the potential benefits from use of the drug in pregnant women with serious or life-threatening conditions may be acceptable despite its risks. Fluconazole should not be taken during pregnancy or if one could become pregnant during treatment without first consulting a doctor.[26] Oral fluconazole is not associated with a significantly increased risk of birth defects overall, although it does increase the odds ratio of tetralogy of Fallot, but the absolute risk is still low.[27] Women using fluconazole during pregnancy have a 50% higher risk of spontaneous abortion.[28]

Fluconazole should not be taken with cisapride (Propulsid) due to the possibility of serious, even fatal, heart problems.[22] In rare cases, severe allergic reactions including anaphylaxis may occur.[29]

Powder for oral suspension contains sucrose and should not be used in patients with hereditary fructose, glucose/galactose malabsorption or sucrase-isomaltase deficiency. Capsules contain lactose and should not be given to patients with rare hereditary problems of galactose intolerance, Lapp lactase deficiency, or glucose-galactose malabsorption [30]

Interactions

Fluconazole is an inhibitor of the human cytochrome P450 system, particularly the isozyme CYP2C19 (CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 to lesser extent) [31] In theory, therefore, fluconazole decreases the metabolism and increases the concentration of any drug metabolised by these enzymes. In addition, its potential effect on QT interval increases the risk of cardiac arrhythmia if used concurrently with other drugs that prolong the QT interval. Berberine has been shown to exert synergistic effects with fluconazole even in drug-resistant Candida albicans infections.[32] Fluconazole may increase the serum concentration of Erythromycin (Risk X: avoid combination).[31]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Like other imidazole- and triazole-class antifungals, fluconazole inhibits the fungal cytochrome P450 enzyme 14α-demethylase. Mammalian demethylase activity is much less sensitive to fluconazole than fungal demethylase. This inhibition prevents the conversion of lanosterol to ergosterol, an essential component of the fungal cytoplasmic membrane, and subsequent accumulation of 14α-methyl sterols.[23] Fluconazole is primarily fungistatic; however, it may be fungicidal against certain organisms in a dose-dependent manner, specifically Cryptococcus.[33]

Pharmacokinetics

Following oral dosing, fluconazole is almost completely absorbed within two hours.[34] Bioavailability is not significantly affected by the absence of stomach acid. Concentrations measured in the urine, tears, and skin are approximately 10 times the plasma concentration, whereas saliva, sputum, and vaginal fluid concentrations are approximately equal to the plasma concentration, following a standard dose range of between 100 mg and 400 mg per day.[35] The elimination half-life of fluconazole follows zero order, and only 10% of elimination is due to metabolism, the remainder being excreted in urine and sweat. Patients with impaired renal function will be at risk of overdose.[22]

In a bulk powder form, it appears as a white crystalline powder, and it is very slightly soluble in water and soluble in alcohol.[36]

History

Fluconazole was patented by Pfizer in 1981 in the United Kingdom and came into commercial use in 1988.[5] Patent expirations occurred in 2004 and 2005.[37]

References

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/psusa/fluconazole-list-nationally-authorised-medicinal-products-psusa/00001404/202003_en.pdf

- Surov, Artem O.; Voronin, Alexander P.; Vasilev, Nikita A.; Churakov, Andrei V.; Perlovich, German L. (20 December 2019). "Cocrystals of Fluconazole with Aromatic Carboxylic Acids: Competition between Anhydrous and Hydrated Solid Forms". Crystal Growth & Design. 20 (2): 1218–1228. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.9b01490. S2CID 213008181.

- "Fluconazole". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Fluconazole (Diflucan): Drug Safety Communication - FDA Evaluating Study Examining Use of Oral Fluconazole (Diflucan) in Pregnancy". FDA. 26 April 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 503. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "The Top 300 of 2019". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- "Fluconazole - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- "US Pharmacist". Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "US Prescribing Information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "IDSA Guidelines: Candida Infections". Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "IDSA Guidelines: Cryptococcal Infections". Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3

- Bennett J. E. (2011). "57. Antifungal Agents". In L.L. Brunton; B.A. Chabner; B.C. Knollmann (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 12e. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Spectrum of fungal susptibility and resistance to fluconazole Archived 2016-03-14 at the Wayback Machine

- "Antifungal Resistance | Fungal Disease | CDC". 25 January 2019. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017.

- "FDA Alert: Diflucan (fluconazole): Drug Safety Communication - Long-term, High-dose Use During Pregnancy May be Associated with Birth Defects". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- "Fluconazole". Monograph. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Product information from Pfizer Inc Archived 2010-01-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Brunton, Laurence L., editor. Knollmann, Björn C., editor. Hilal-Dandan, Randa, editor. (2018). Goodman & Gilman's : the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 13e. McGraw-Hill Education LLC. ISBN 978-1-259-58473-2. OCLC 1075550900.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd. Diflucan (Australian Approved Product Information). West Ryde (NSW): Pfizer Australia; 2004.

- Pinto, Angie; Chan, Raymond C. (2009). "Lack of Allergic Cross-Reactivity between Fluconazole and Voriconazole" (PDF). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 53 (4): 1715–1716. doi:10.1128/AAC.01500-08. PMC 2663085. PMID 19164151. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- Kragie, Laura; Turner, Stephanie D.; Patten, Christopher J.; Crespi, Charles L.; Stresser, David M. (2002). "Assessing Pregnancy Risks of Azole Antifungals Using a High Throughput Aromatase Inhibition Assay". Endocrine Research. 28 (3): 129–40. doi:10.1081/ERC-120015045. PMID 12489563. S2CID 8282678.

- Fluconazole Archived 2012-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, PubMed Health

- Mølgaard-Nielsen, D.; Pasternak, B. R.; Hviid, A. (2013). "Use of Oral Fluconazole during Pregnancy and the Risk of Birth Defects". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (9): 830–839. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301066. PMID 23984730.

- Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, Hviid A, Pasternak B (5 January 2016). "Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth". JAMA. 315 (1): 58–67. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.17844. ISSN 1538-3598. PMID 26746458.

- Rang, H. P, author. Rang & Dale's pharmacology. ISBN 978-0-7020-5362-7. OCLC 942814866.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Diflucan (Fluconazole) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". reference.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014.

- "Login". Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- Xu, Yi; Wang, Yan; Yan, Lan; Liang, Rong-Mei; Dai, Bao-Di; Tang, Ren-Jie; Gao, Ping-Hui; Jiang, Yuan-Ying (2009). "Proteomic Analysis Reveals a Synergistic Mechanism of Fluconazole and Berberine against Fluconazole-ResistantCandida albicans: Endogenous ROS Augmentation". Journal of Proteome Research. 8 (11): 5296–5304. doi:10.1021/pr9005074. ISSN 1535-3893. PMID 19754040.

- Longley, Nicky; Muzoora, Conrad; Taseera, Kabanda; Mwesigye, James; Rwebembera, Joselyne; Chakera, Ali; Wall, Emma; Andia, Irene; Jaffar, Shabbar; Harrison, Thomas S. (2008). "Dose Response Effect of High‐Dose Fluconazole for HIV‐Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis in Southwestern Uganda". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 47 (12): 1556–1561. doi:10.1086/593194. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 18990067.

- Katzung, Bertram G. (30 November 2017). Basic & clinical pharmacology. ISBN 978-1-259-64115-2. OCLC 1035129378.

- Whalen, Karen, editor. Feild, Carinda, editor. Radhakrishnan, Rajan, editor. (21 September 2018). Lippincott Illustrated Reviews Pharmacology. ISBN 978-1-4963-8413-3. OCLC 1114483879.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - MP Biomedicals Archived 2009-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- "Pfizer to Expand Fluconazole Donation Program to More than 50 Developing Nations". Kaiser Health News. 7 June 2001. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

External links

- "Fluconazole". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Doi : Evolution of Fluconazole-Resistant Candida albicans Strains by Drug-Induced Mating Competence and Parasexual Recombination