Gerrymandering

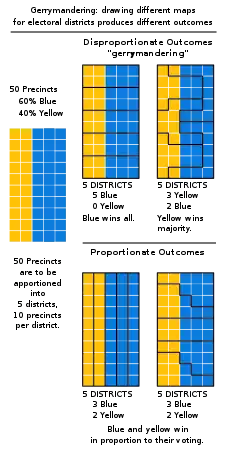

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (/ˈdʒɛrimændərɪŋ/, originally /ˈɡɛrimændərɪŋ/)[1][2] is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent of creating undue advantage for a party, group, or socio-economic class within the constituency. The manipulation may consist of "cracking" (diluting the voting power of the opposing party's supporters across many districts) or "packing" (concentrating the opposing party's voting power in one district to reduce their voting power in other districts).[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Elections |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

Gerrymandering can also be used to protect incumbents. Wayne Dawkins describes it as politicians picking their voters instead of voters picking their politicians.[4]

The term gerrymandering is named after American politician Elbridge Gerry,[lower-alpha 1][5] Vice President of the United States at the time of his death, who, as Governor of Massachusetts in 1812, signed a bill that created a partisan district in the Boston area that was compared to the shape of a mythological salamander. The term has negative connotations and gerrymandering is almost always considered a corruption of the democratic process. The resulting district is known as a gerrymander (/ˈdʒɛriˌmændər, ˈɡɛri-/). The word is also a verb for the process.[6][7]

Etymology

The word gerrymander (originally written Gerry-mander; a portmanteau of the name Gerry and the animal salamander) was used for the first time in the Boston Gazette[lower-alpha 2] on 26 March 1812 in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. This word was created in reaction to a redrawing of Massachusetts Senate election districts under Governor Elbridge Gerry, later Vice President of the United States. Gerry, who personally disapproved of the practice, signed a bill that redistricted Massachusetts for the benefit of the Democratic-Republican Party. When mapped, one of the contorted districts in the Boston area was said to resemble a mythological salamander.[8] Appearing with the term, and helping spread and sustain its popularity, was a political cartoon depicting a strange animal with claws, wings and a dragon-like head that supposedly resembled the oddly shaped district.

The cartoon was most likely drawn by Elkanah Tisdale, an early 19th-century painter, designer, and engraver who was living in Boston at the time.[9] Tisdale had the engraving skills to cut the woodblocks to print the original cartoon.[10] These woodblocks survive and are preserved in the Library of Congress.[11] The creator of the term gerrymander, however, may never be definitively established. Historians widely believe that the Federalist newspaper editors Nathan Hale and Benjamin and John Russell coined the term, but the historical record does not have definitive evidence as to who created or uttered the word for the first time.[12]

The redistricting was a notable success for Gerry's Democratic-Republican Party. In the 1812 election, both the Massachusetts House and governorship were comfortably won by Federalists, losing Gerry his job. The redistricted state Senate, however, remained firmly in Democratic-Republican hands.[8]

The word gerrymander was reprinted numerous times in Federalist newspapers in Massachusetts, New England, and nationwide during the remainder of 1812.[13] This suggests an organized activity of the Federalists to disparage Governor Gerry in particular, and the growing Democratic-Republican party in general. Gerrymandering soon began to be used to describe other cases of district shape manipulation for partisan gain in other states. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word's acceptance was marked by its publication in a dictionary (1848) and in an encyclopedia (1868).[14] Since the letter g of the eponymous Gerry is pronounced with a hard g /ɡ/ as in get, the word gerrymander was originally pronounced /ˈɡɛrimændər/. However, pronunciation as /ˈdʒɛrimændər/, with a soft g /dʒ/ as in gentle, has become the dominant pronunciation. Residents of Marblehead, Massachusetts, Gerry's hometown, continue to use the original pronunciation.[15]

From time to time, other names have been suffixed with -mander to tie a particular effort to a particular politician or group. Examples are the 1852 "Henry-mandering", "Jerrymander" (referring to California Governor Jerry Brown),[16] "Perrymander" (a reference to Texas Governor Rick Perry),[17][18] and "Tullymander" (after the Irish politician James Tully),[19] and "Bjelkemander" (referencing Australian politician Joh Bjelke-Petersen).

Tactics

The primary goals of gerrymandering are to maximize the effect of supporters' votes and to minimize the effect of opponents' votes. A partisan gerrymander's main purpose is to influence not only the districting statute but the entire corpus of legislative decisions enacted in its path.[20]

These can be accomplished in a number of ways:[21]

- "Cracking" involves spreading voters of a particular type among many districts in order to deny them a sufficiently large voting bloc in any particular district.[21] Political parties in charge of redrawing district lines may create more "cracked" districts as a means of retaining, and possibly even expanding, their legislative power. By "cracking" districts, a political party could maintain, or gain, legislative control by ensuring that the opposing party's voters are not the majority in specific districts.[22][23] For example, the voters in an urban area could be split among several districts in each of which the majority of voters are suburban, on the presumption that the two groups would vote differently, and the suburban voters would be far more likely to get their way in the elections.

- "Packing" is concentrating many voters of one type into a single electoral district to reduce their influence in other districts.[21][23] In some cases, this may be done to obtain representation for a community of common interest (such as to create a majority-minority district), rather than to dilute that interest over several districts to a point of ineffectiveness (and, when minority groups are involved, to avoid likely lawsuits charging racial discrimination). When the party controlling the districting process has a statewide majority, packing is usually not necessary to attain partisan advantage; the minority party can generally be "cracked" everywhere. Packing is therefore more likely to be used for partisan advantage when the party controlling the districting process has a statewide minority, because by forfeiting a few districts packed with the opposition, cracking can be used in forming the remaining districts.

- "Hijacking" redraws two districts in such a way as to force two incumbents to run against each other in one district, ensuring that one of them will be eliminated.[21]

- "Kidnapping" moves an incumbent's home address into another district.[21] Reelection can become more difficult when the incumbent no longer resides in the district, or possibly faces reelection from a new district with a new voter base. This is often employed against politicians who represent multiple urban areas, in which larger cities will be removed from the district in order to make the district more rural.

These tactics are typically combined in some form, creating a few "forfeit" seats for packed voters of one type in order to secure more seats and greater representation for voters of another type. This results in candidates of one party (the one responsible for the gerrymandering) winning by small majorities in most of the districts, and another party winning by a large majority in only a few of the districts.[24] Any party that endeavors to make a district more favorable to voting for them based on the physical boundary is gerrymandering.

Effects

Gerrymandering is effective because of the wasted vote effect. Wasted votes are votes that did not contribute to electing a candidate, either because they were in excess of the bare minimum needed for victory or because the candidate lost. By moving geographic boundaries, the incumbent party packs opposition voters into a few districts they will already win, wasting the extra votes. Other districts are more tightly constructed with the opposition party allowed a bare minority count, thereby wasting all the minority votes for the losing candidate. These districts constitute the majority of districts and are drawn to produce a result favoring the incumbent party.[25]

A quantitative measure of the effect of gerrymandering is the efficiency gap, computed from the difference in the wasted votes for two different political parties summed over all the districts.[26][27] Citing in part an efficiency gap of 11.69% to 13%, a U.S. District Court in 2016 ruled against the 2011 drawing of Wisconsin legislative districts. In the 2012 election for the state legislature, that gap in wasted votes meant that one party had 48.6% of the two-party votes but won 61% of the 99 districts.[28]

While the wasted vote effect is strongest when a party wins by narrow margins across multiple districts, gerrymandering narrow margins can be risky when voters are less predictable. To minimize the risk of demographic or political shifts swinging a district to the opposition, politicians can create more packed districts, leading to more comfortable margins in unpacked ones.

Effect on electoral competition

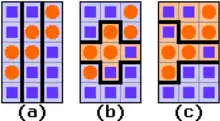

(a), creates 3 mixed-type districts which yields a 3–0 win to Plum—a disproportional result considering the statewide 9:6 Plum majority.

(b), Orange wins the central (+ shaped) district while Plum wins the upper and lower districts. The 2–1 result reflects the statewide vote ratio.

(c), gerrymandering techniques ensure a 2–1 win to the statewide minority Orange party.

Some political science research suggests that, contrary to common belief, gerrymandering does not decrease electoral competition, and can even increase it. Some say that, rather than packing the voters of their party into uncompetitive districts, party leaders tend to prefer to spread their party's voters into multiple districts, so that their party can win a larger number of races.[29] (See scenario (c) in the box.) This may lead to increased competition. Instead of gerrymandering, some researchers find that other factors, such as partisan polarization and the incumbency advantage, have driven the recent decreases in electoral competition.[30] Similarly, a 2009 study found that "congressional polarization is primarily a function of the differences in how Democrats and Republicans represent the same districts rather than a function of which districts each party represents or the distribution of constituency preferences."[31]

One state in which gerrymandering has arguably had an adverse effect on electoral competition is California. In 2000, a bipartisan redistricting effort redrew congressional district lines in ways that all but guaranteed incumbent victories; as a result, California saw only one congressional seat change hands between 2000 and 2010. In response to this obvious gerrymandering, a 2010 referendum in California gave the power to redraw congressional district lines to the California Citizens Redistricting Commission, which had been created to draw California State Senate and Assembly districts by another referendum in 2008. In stark contrast to the redistricting efforts that followed the 2000 census, the redistricting commission has created a number of the most competitive congressional districts in the country.[32]

Increased incumbent advantage and campaign costs

The effect of gerrymandering for incumbents is particularly advantageous, as incumbents are far more likely to be reelected under conditions of gerrymandering. For example, in 2002, according to political scientists Norman Ornstein and Thomas Mann, only four challengers were able to defeat incumbent members of the U.S. Congress, the lowest number in modern American history.[33] Incumbents are likely to be of the majority party orchestrating a gerrymander, and incumbents are usually easily renominated in subsequent elections, including incumbents among the minority.

Mann, a Senior Fellow of Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution, has also noted that "Redistricting is a deeply political process, with incumbents actively seeking to minimize the risk to themselves (via bipartisan gerrymanders) or to gain additional seats for their party (via partisan gerrymanders)".[34] The bipartisan gerrymandering that Mann mentions refers to the fact that legislators often also draw distorted legislative districts even when such redistricting does not provide an advantage to their party.

Gerrymandering of state legislative districts can effectively guarantee an incumbent's victory by 'shoring up' a district with higher levels of partisan support, without disproportionately benefiting a particular political party. This can be highly problematic from a governance perspective, because forming districts to ensure high levels of partisanship often leads to higher levels of partisanship in legislative bodies. If a substantial number of districts are designed to be polarized, then those districts' representation will also likely act in a heavily partisan manner, which can create and perpetuate partisan gridlock.

This demonstrates that gerrymandering can have a deleterious effect on the principle of democratic accountability. With uncompetitive seats/districts reducing the fear that incumbent politicians may lose office, they have less incentive to represent the interests of their constituents, even when those interests conform to majority support for an issue across the electorate as a whole. Incumbent politicians may look out more for their party's interests than for those of their constituents.

Gerrymandering can affect campaign costs for district elections. If districts become increasingly stretched out, candidates must pay increased costs for transportation and trying to develop and present campaign advertising across a district.[35] The incumbent's advantage in securing campaign funds is another benefit of his or her having a gerrymandered secure seat.

Less descriptive representation

Gerrymandering also has significant effects on the representation received by voters in gerrymandered districts. Because gerrymandering can be designed to increase the number of wasted votes among the electorate, the relative representation of particular groups can be drastically altered from their actual share of the voting population. This effect can significantly prevent a gerrymandered system from achieving proportional and descriptive representation, as the winners of elections are increasingly determined by who is drawing the districts rather than the preferences of the voters.

Gerrymandering may be advocated to improve representation within the legislature among otherwise underrepresented minority groups by packing them into a single district. This can be controversial, as it may lead to those groups' remaining marginalized in the government as they become confined to a single district. Candidates outside that district no longer need to represent them to win elections.

As an example, much of the redistricting conducted in the United States in the early 1990s involved the intentional creation of additional "majority-minority" districts where racial minorities such as African Americans were packed into the majority. This "maximization policy" drew support by both the Republican Party (who had limited support among African Americans and could concentrate their power elsewhere) and by minority representatives elected as Democrats from these constituencies, who then had safe seats.

The 2012 election provides a number of examples as to how partisan gerrymandering can adversely affect the descriptive function of states' congressional delegations. In Pennsylvania, for example, Democratic candidates for the House of Representatives received 83,000 more votes than Republican candidates, yet the Republican-controlled redistricting process in 2010 resulted in Democrats losing to their Republican counterparts in 13 out of Pennsylvania's 18 districts.[36]

In the seven states where Republicans had complete control over the redistricting process, Republican House candidates received 16.7 million votes and Democratic House candidates received 16.4 million votes. The redistricting resulted in Republican victories in 73 out of the 107 affected seats; in those 7 states, Republicans received 50.4% of the votes but won in over 68% of the congressional districts.[37] While it is but one example of how gerrymandering can have a significant effect on election outcomes, this kind of disproportional representation of the public will seems to be problematic for the legitimacy of democratic systems, regardless of one's political affiliation.

In Michigan, redistricting was constructed by a Republican Legislature in 2011.[38] Federal congressional districts were so designed that cities such as Battle Creek, Grand Rapids, Jackson, Kalamazoo, Lansing, and East Lansing were separated into districts with large conservative-leaning hinterlands that essentially diluted the Democratic votes in those cities in Congressional elections. Since 2010 not one of those cities is within a district in which a Democratic nominee for the House of Representatives has a reasonable chance of winning, short of Democratic landslide.

Incumbent gerrymandering

Gerrymandering can also be done to help incumbents as a whole, effectively turning every district into a packed one and greatly reducing the potential for competitive elections. This is particularly likely to occur when the minority party has significant obstruction power—unable to enact a partisan gerrymander, the legislature instead agrees on ensuring their own mutual reelection.

In an unusual occurrence in 2000, for example, the two dominant parties in the state of California cooperatively redrew both state and Federal legislative districts to preserve the status quo, ensuring the electoral safety of the politicians from unpredictable voting by the electorate. This move proved completely effective, as no State or Federal legislative office changed party in the 2004 election, although 53 congressional, 20 state senate, and 80 state assembly seats were potentially at risk.

In 2006, the term "70/30 District" came to signify the equitable split of two evenly split (i.e. 50/50) districts. The resulting districts gave each party a guaranteed seat and retained their respective power base.

Prison-based gerrymandering

Prison-based gerrymandering occurs when prisoners are counted as residents of a particular district, increasing the district's population with non-voters when assigning political apportionment. This phenomenon violates the principle of one person, one vote because, although many prisoners come from (and return to) urban communities, they are counted as "residents" of the rural districts that contain large prisons, thereby artificially inflating the political representation in districts with prisons at the expense of voters in all other districts without prisons.[39] Others contend that prisoners should not be counted as residents of their original districts when they do not reside there and are not legally eligible to vote.[40][41]

Changes to achieve competitive elections

Due to the perceived issues associated with gerrymandering and its effect on competitive elections and democratic accountability, numerous countries have enacted reforms making the practice more difficult or less effective. Countries such as the U.K., Australia, Canada and most of those in Europe have transferred responsibility for defining constituency boundaries to neutral or cross-party bodies. In Spain, they are constitutionally fixed since 1978.[42] Open party-list proportional representation makes gerrymandering obsolete by erasing district lines and empowering voters to rank a list of candidates put forth by any party (Main article: Party-list proportional representation). This method is used in Austria, Brazil, Sweden, and Switzerland among others.

In the United States, however, such reforms are controversial and frequently meet particularly strong opposition from groups that benefit from gerrymandering. In a more neutral system, they might lose considerable influence.

Redistricting by neutral or cross-party agency

The most commonly advocated electoral reform proposal targeted at gerrymandering is to change the redistricting process. Under these proposals, an independent and presumably objective commission is created specifically for redistricting, rather than having the legislature do it.

This is the system used in the United Kingdom, where the independent boundary commissions determine the boundaries for constituencies in the House of Commons and the devolved legislatures, subject to ratification by the body in question (almost always granted without debate). A similar situation exists in Australia where the independent Australian Electoral Commission and its state-based counterparts determine electoral boundaries for federal, state and local jurisdictions.

To help ensure neutrality, members of a redistricting agency may be appointed from relatively apolitical sources such as retired judges or longstanding members of the civil service, possibly with requirements for adequate representation among competing political parties. Additionally, members of the board can be denied access to information that might aid in gerrymandering, such as the demographic makeup or voting patterns of the population.

As a further constraint, consensus requirements can be imposed to ensure that the resulting district map reflects a wider perception of fairness, such as a requirement for a supermajority approval of the commission for any district proposal. Consensus requirements, however, can lead to deadlock, such as occurred in Missouri following the 2000 census. There, the equally numbered partisan appointees were unable to reach consensus in a reasonable time, and consequently the courts had to determine district lines.

In the U.S. state of Iowa, the nonpartisan Legislative Services Bureau (LSB, akin to the U.S. Congressional Research Service) determines boundaries of electoral districts. Aside from satisfying federally mandated contiguity and population equality criteria, the LSB mandates unity of counties and cities. Consideration of political factors such as location of incumbents, previous boundary locations, and political party proportions is specifically forbidden. Since Iowa's counties are chiefly regularly shaped polygons, the LSB process has led to districts that follow county lines.[33]

In 2005, the U.S. state of Ohio had a ballot measure to create an independent commission whose first priority was competitive districts, a sort of "reverse gerrymander". A complex mathematical formula was to be used to determine the competitiveness of a district. The measure failed voter approval chiefly due to voter concerns that communities of interest would be broken up.[43]

In 2017, the Open Our Democracy Act of 2017 was submitted to the US House of Representatives by Rep. Delaney as a means to implement non-partisan redistricting.

Redistricting by partisan competition

Many redistricting reforms seek to remove partisanship to ensure fairness in the redistricting process. The I-cut-you-choose method achieves fairness by putting the two major-parties in direct competition. I-cut-you-choose is a fair division method to divide resources amongst two parties, regardless of which party cuts first.[44] This method typically relies on assumptions of contiguity of districts but ignores all other constraints such as keeping communities of interest together. This method has been applied to nominal redistricting problems[45] but it generally has less public interest than other types of redistricting reforms. The I-cut-you-choose concept was popularized by the board game Berrymandering. Problems with this method arise when minor parties are shut-out of the process which will reinforce the two-party system. Additionally, while this method is provably fair to the two parties creating the districts, it is not necessarily fair to the communities they represent.

Transparency regulations

When a single political party controls both legislative houses of a state during redistricting, both Democrats and Republicans have displayed a marked propensity for couching the process in secrecy; in May 2010, for example, the Republican National Committee held a redistricting training session in Ohio where the theme was "Keep it Secret, Keep it Safe".[46] The need for increased transparency in redistricting processes is clear; a 2012 investigation by The Center for Public Integrity reviewed every state's redistricting processes for both transparency and potential for public input, and ultimately assigned 24 states grades of either D or F.[47]

In response to these types of problems, redistricting transparency legislation has been introduced to US Congress a number of times in recent years, including the Redistricting Transparency Acts of 2010, 2011, and 2013.[48][49][50] Such policy proposals aim to increase the transparency and responsiveness of the redistricting systems in the US. The merit of increasing transparency in redistricting processes is based largely on the premise that lawmakers would be less inclined to draw gerrymandered districts if they were forced to defend such districts in a public forum.

Changing the voting system

As gerrymandering relies on the wasted-vote effect, the use of a different voting system with fewer wasted votes can help reduce gerrymandering. In particular, the use of multi-member districts alongside voting systems establishing proportional representation such as single transferable voting can reduce wasted votes and gerrymandering. Semi-proportional voting systems such as single non-transferable vote or cumulative voting are relatively simple and similar to first past the post and can also reduce the proportion of wasted votes and thus potential gerrymandering. Electoral reformers have advocated all three as replacement systems.[51]

Electoral systems with various forms of proportional representation are now found in nearly all European countries, resulting in multi-party systems (with many parties represented in the parliaments) with higher voter attendance in the elections,[52] fewer wasted votes, and a wider variety of political opinions represented.

Electoral systems with election of just one winner in each district (i.e., "winner-takes-all" electoral systems) and no proportional distribution of extra mandates to smaller parties tend to create two-party systems. This effect, labeled Duverger's law by political scientists, was described by Maurice Duverger.[53]

Using fixed districts

Another way to avoid gerrymandering is simply to stop redistricting altogether and use existing political boundaries such as state, county, or provincial lines. While this prevents future gerrymandering, any existing advantage may become deeply ingrained. The United States Senate, for instance, has more competitive elections than the House of Representatives due to the use of existing state borders rather than gerrymandered districts—Senators are elected by their entire state, while Representatives are elected in legislatively drawn districts.

The use of fixed districts creates an additional problem, however, in that fixed districts do not take into account changes in population. Individual voters can come to have very different degrees of influence on the legislative process. This malapportionment can greatly affect representation after long periods of time or large population movements. In the United Kingdom during the Industrial Revolution, several constituencies that had been fixed since they gained representation in the Parliament of England became so small that they could be won with only a handful of voters (rotten boroughs). Similarly, in the U.S. the Alabama Legislature refused to redistrict for more than 60 years, despite major changes in population patterns. By 1960 less than a quarter of the state's population controlled the majority of seats in the legislature.[54] This practice of using fixed districts for state legislatures was effectively banned in the United States after the Reynolds v. Sims Supreme Court decision in 1964, establishing a rule of one man, one vote.

Objective rules to create districts

Another means to reduce gerrymandering is to create objective, precise criteria with which any district map must comply. Courts in the United States, for instance, have ruled that congressional districts must be contiguous in order to be constitutional.[55] This, however, is not a particularly effective constraint, as very narrow strips of land with few or no voters in them may be used to connect separate regions for inclusion in one district, as is the case in Illinois's 4th congressional district.

Depending on the distribution of voters for a particular party, metrics that maximize compactness can be opposed to metrics that minimize the efficiency gap. For example, in the United States, voters registered with the Democratic Party tend to be concentrated in cities, potentially resulting in a large number of "wasted" votes if compact districts are drawn around city populations. Neither of these metrics take into consideration other possible goals,[56] such as proportional representation based on other demographic characteristics (such as race, ethnicity, gender, or income), maximizing competitiveness of elections (the greatest number of districts where party affiliation is 50/50), avoiding splits of existing government units (like cities and counties), and ensuring representation of major interest groups (like farmers or voters in a specific transportation corridor), though any of these could be incorporated into a more complicated metric.

Minimum district to convex polygon ratio

One method is to define a minimum district to convex polygon ratio . To use this method, every proposed district is circumscribed by the smallest possible convex polygon (its convex hull; think of stretching a rubberband around the outline of the district). Then, the area of the district is divided by the area of the polygon; or, if at the edge of the state, by the portion of the area of the polygon within state boundaries.

The advantages of this method are that it allows a certain amount of human intervention to take place (thus solving the Colorado problem of splitline districting); it allows the borders of the district to follow existing jagged subdivisions, such as neighbourhoods or voting districts (something isoperimetric rules would discourage); and it allows concave coastline districts, such as the Florida gulf coast area. It would mostly eliminate bent districts, but still permit long, straight ones. However, since human intervention is still allowed, the gerrymandering issues of packing and cracking would still occur, just to a lesser extent.

Shortest splitline algorithm

The Center for Range Voting has proposed[57] a way to draw districts by a simple algorithm.[58] The algorithm uses only the shape of the state, the number N of districts wanted, and the population distribution as inputs. The algorithm (slightly simplified) is:

- Start with the boundary outline of the state.

- Let N=A+B where N is the number of districts to create, and A and B are two whole numbers, either equal (if N is even) or differing by exactly one (if N is odd). For example, if N is 10, each of A and B would be 5. If N is 7, A would be 4 and B would be 3.

- Among all possible straight lines that split the state into two parts with the population ratio A:B, choose the shortest. If there are two or more such shortest lines, choose the one that is most north–south in direction; if there is still more than one possibility, choose the westernmost.

- We now have two hemi-states, each to contain a specified number (namely A and B) of districts. Handle them recursively via the same splitting procedure.

- Any human residence that is split in two or more parts by the resulting lines is considered to be a part of the most north-eastern of the resulting districts; if this does not decide it, then of the most northern.

This district-drawing algorithm has the advantages of simplicity, ultra-low cost, a single possible result (thus no possibility of human interference), lack of intentional bias, and it produces simple boundaries that do not meander needlessly. It has the disadvantage of ignoring geographic features such as rivers, cliffs, and highways and cultural features such as tribal boundaries. This landscape oversight causes it to produce districts different from those a human would produce. Ignoring geographic features can induce very simple boundaries.

While most districts produced by the method will be fairly compact and either roughly rectangular or triangular, some of the resulting districts can still be long and narrow strips (or triangles) of land.

Like most automatic redistricting rules, the shortest splitline algorithm will fail to create majority-minority districts, for both ethnic and political minorities, if the minority populations are not very compact. This might reduce minority representation.

Another criticism of the system is that splitline districts sometimes divide and diffuse the voters in a large metropolitan area. This condition is most likely to occur when one of the first splitlines cuts through the metropolitan area. It is often considered a drawback of the system because residents of the same agglomeration are assumed to be a community of common interest. This is most evident in the splitline allocation of Colorado.[59] However, in cases when the splitline divides a large metropolitan area, it is usually because that large area has enough population for multiple districts. In cases which the large area only has the population for one district, then the splitline usually results in the urban area being in one district with the other district being rural.

As of July 2007, shortest-splitline redistricting pictures, based on the results of the 2000 census, are available for all 50 states.[60]

Minimum isoperimetric quotient

It is possible to define a specific minimum isoperimetric quotient,[61] proportional to the ratio between the area and the square of the perimeter of any given congressional voting district. Although technologies presently exist to define districts in this manner, there are no rules in place mandating their use, and no national movement to implement such a policy. One problem with the simplest version of this rule is that it would prevent incorporation of jagged natural boundaries, such as rivers or mountains; when such boundaries are required, such as at the edge of a state, certain districts may not be able to meet the required minima. One way of avoiding this problem is to allow districts which share a border with a state border to replace that border with a polygon or semi-circle enclosing the state boundary as a kind of virtual boundary definition, but using the actual perimeter of the district whenever this occurs inside the state boundaries. Enforcing a minimum isoperimetric quotient would encourage districts with a high ratio between area and perimeter.[61]

Efficiency gap calculation

The efficiency gap is a simply-calculable measure that can show the effects of gerrymandering.[62] It measures wasted votes for each party: the sum of votes cast in losing districts (losses due to cracking) and excess votes cast in winning districts (losses due to packing). The difference in these wasted votes are divided by total votes cast, and the resulting percentage is the efficiency gap.

In 2017, Boris Alexeev and Dustin Mixon proved that "sometimes, a small efficiency gap is only possible with bizarrely shaped districts". This means that it is mathematically impossible to always devise boundaries which would simultaneously meet certain Polsby–Popper and efficiency gap targets.[63][64][65]

Use of databases and computer technology

The introduction of modern computers alongside the development of elaborate voter databases and special districting software has made gerrymandering a far more precise science. Using such databases, political parties can obtain detailed information about every household including political party registration, previous campaign donations, and the number of times residents voted in previous elections and combine it with other predictors of voting behavior such as age, income, race, or education level. With this data, gerrymandering politicians can predict the voting behavior of each potential district with an astonishing degree of precision, leaving little chance for creating an accidentally competitive district.

On the other hand, the introduction of modern computers would allow the United States Census Bureau to calculate more equal populations in every voting district that are based only on districts being the most compact and equal populations. This could be done easily using their Block Centers based on the Global Positioning System rather than street addresses. With this data, gerrymandering politicians will not be in charge, thus allowing competitive districts again.

Online web apps such as Dave's Redistricting have allowed users to simulate redistricting states into legislative districts as they wish.[66][67] According to Bradlee, the software was designed to "put power in people's hands," and so that they "can see how the process works, so it's a little less mysterious than it was 10 years ago."[68]

Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) can measure the extent to which redistricting plans favor a particular party or group in election, and can support automated redistricting simulators.[69]

Voting systems

First-past-the-post

Gerrymandering is most likely to emerge, in majoritarian systems, where the country is divided into several voting districts and the candidate with the most votes wins the district. If the ruling party is in charge of drawing the district lines, it can abuse the fact that in a majoritarian system all votes that do not go to the winning candidate are essentially irrelevant to the composition of a new government. Even though gerrymandering can be used in other voting systems, it has the most significant impact on voting outcomes in first-past-the-post systems.[70] Partisan redrawing of district lines is particularly harmful to democratic principles in majoritarian two-party systems. In general, two party systems tend to be more polarized than proportional systems.[71] Possible consequences of gerrymandering in such a system can be an amplification of polarization in politics and a lack of representation of minorities, as a large part of the constituency is not represented in policy making. However, not every state using a first-past-the-post system is being confronted with the negative impacts of gerrymandering. Some countries, such as Australia, Canada and the UK, authorize non-partisan organizations to set constituency boundaries in attempt to prevent gerrymandering.[72]

Proportional systems

The introduction of a proportional system is often proposed as the most effective solution to partisan gerrymandering.[73] In such systems the entire constituency is being represented proportionally to their votes. Even though voting districts can be part of a proportional system, the redrawing of district lines would not benefit a party, as those districts are mainly of organizational value. For example, instead of having three districts, a single large district would exist where the top three candidates in the election would all represent the district. It would be harder to gerrymander a district where there are multiple winners from that district.

Mixed systems

In mixed systems that use proportional and majoritarian voting principles, the usage of gerrymandering is a constitutional obstacle that states have to deal with. However, in mixed systems the advantage a political actor can potentially gain from redrawing district lines is much less than in majoritarian systems. In mixed systems voting districts are mostly being used to avoid that elected parliamentarians are getting too detached from their constituency. The principle which determines the representation in parliament is usually the proportional aspect of the voting system. Seats in parliament are being allocated to each party in accordance to the proportion of their overall votes. In most mixed systems, winning a voting district merely means that a candidate is guaranteed a seat in parliament, but does not expand a party's share in the overall seats.[74] However, gerrymandering can still be used to manipulate the outcome in voting districts. In most democracies with a mixed system, non-partisan institutions are in charge of drawing district lines and therefore Gerrymandering is a less common phenomenon.

Difference from malapportionment

Gerrymandering should not be confused with malapportionment, whereby the number of eligible voters per elected representative can vary widely without relation to how the boundaries are drawn. Nevertheless, the -mander suffix has been applied to particular malapportionments. Sometimes political representatives use both gerrymandering and malapportionment to try to maintain power.[75][76]

Examples

Several western democracies, notably Israel, the Netherlands and Slovakia employ an electoral system with only one (nationwide) voting district for election of national representatives. This virtually precludes gerrymandering.[77][78] Other European countries such as Austria, the Czech Republic or Sweden, among many others, have electoral districts with fixed boundaries (usually one district for each administrative division). The number of representatives for each district can change after a census due to population shifts, but their boundaries do not change. This also effectively eliminates gerrymandering.

Additionally, many countries where the president is directly elected by the citizens (e.g. France, Poland, among others) use only one electoral district for presidential election, despite using multiple districts to elect representatives.

National

Gerrymandering has not typically been considered a problem in the Australian electoral system largely because drawing of electoral boundaries has typically been done by non-partisan electoral commissions. There have been historical cases of malapportionment, whereby the distribution of electors to electorates was not in proportion to the population in several states.

In the 1998 Australian federal election, the opposition Australian Labor Party, led by Kim Beazley, received 50.98% of the two-party-preferred vote in the House of Representatives, but won only 67/148 seats (45.05%). The incumbent Liberal National Coalition government led by Prime Minister John Howard won 49.02% of the vote and 80 of 148 seats (54.05%). Compared to the previous election, there was a swing of 4.61% against the Coalition, who lost 14 seats. After Howard's victory, many Coalition seats were extremely marginal, having only been won by less than 1% (less than 1200 votes). This election result is generally not attributed to gerrymandering or malapportionment.

South Australia

Sir Thomas Playford was Premier of the state of South Australia from 1938 to 1965 as a result of a system of malapportionment, which became known as the Playmander, despite it not strictly speaking involving a gerrymander.[79]

More recently the nominally independent South Australian Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission has been accused of favouring the Australian Labor Party, as the party has been able to form government in four of the last seven elections, despite receiving a lower two-party preferred vote.[80]

Queensland

In the state of Queensland, malapportionment combined with a gerrymander under Country Party Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen (knighted by Queen Elizabeth II at his own request) became nicknamed the Bjelkemander in the 1970s and 1980s.[81]

The malapportionment had been originally designed to favour rural areas in the 1930s-1950s by a Labor government who drew their support from agricultural and mine workers in rural areas. This helped Labor to stay in government from 1932–1957. As demographics and political views shifted over time, this system came to favour the Country Party instead.

The Country Party led by Frank Nicklin came to power in 1957, deciding to keep the malapportionment that favoured them. In 1968, Joh Bjelke-Petersen became leader of the Country Party and Premier. In the 1970s, he further expanded the malapportionment and gerrymandering which then became known as the Bjelkemander. Under the system, electoral boundaries were drawn so that rural electorates had as few as half as many voters as metropolitan ones and regions with high levels of support for the Labor Party were concentrated into fewer electorates, allowing Bjelke-Petersen's government to remain in power for despite attracting substantially less than 50% of the vote.

In the 1986 election, for example, the National Party received 39.64% of the first preference vote and won 49 seats (in the 89 seat Parliament) whilst the Labor Opposition received 41.35% but won only 30 seats.[82] Bjelke-Petersen also used the system to disadvantage Liberal Party (traditionally allied with the Country Party) voters in urban areas, allowing Bjelke-Petersen's Country Party to rule alone, shunning the Liberals.

Bjelke-Petersen also used Queensland Police brutality to quell protests, and Queensland under his government was frequently described as a police state. In 1987 he was eventually forced to resign in disgrace after the Fitzgerald Inquiry revealed wide-ranging corruption in his cabinet and the Queensland Police, resulting in the prosecution and jailing of Country Party members. Before resigning, Bjelke-Petersen asked the Governor of Queensland to sack his own cabinet, in an unsuccessful attempt to cling to power. Labor won the next election, and have remained the dominant party in Queensland since then. The Country Party and Liberal Party eventually merged in Queensland to become the Liberal-National Party, while the Country Party in other states was renamed as the National Party.

Bahamas

The 1962 Bahamian general election was likely influenced by gerrymandering.[83]

Canada

Gerrymandering used to be prominent in Canadian politics, but is no longer prominent, after independent electoral boundary redistribution commissions were established in all provinces.[84][85] Early in Canadian history, both the federal and provincial levels used gerrymandering to try to maximize partisan power. When Alberta and Saskatchewan were admitted to Confederation in 1905, their original district boundaries were set forth in the respective Alberta and Saskatchewan Acts. Federal Liberal cabinet members devised the boundaries to ensure the election of provincial Liberal governments.[86] British Columbia used a combination of single-member and dual-member constituencies to solidify the power of the centre-right British Columbia Social Credit Party until 1991.

Since responsibility for drawing federal and provincial electoral boundaries was handed over to independent agencies, the problem has largely been eliminated at those levels of government. Manitoba was the first province to authorize a non-partisan group to define constituency boundaries in the 1950s.[84] In 1964, the federal government delegated the drawing of boundaries for federal electoral districts to the non-partisan agency Elections Canada which answers to Parliament rather than the government of the day.

As a result, gerrymandering is not generally a major issue in Canada except at the civic level.[87] Although city wards are recommended by independent agencies, city councils occasionally overrule them. That is much more likely if the city is not homogenous and different neighborhoods have sharply different opinions about city policy direction.

In 2006, a controversy arose in Prince Edward Island over the provincial government's decision to throw out an electoral map drawn by an independent commission. Instead, they created two new maps. The government adopted the second of them, which was designed by the caucus of the governing Progressive Conservative Party of Prince Edward Island. Opposition parties and the media attacked Premier Pat Binns for what they saw as gerrymandering of districts. Among other things, the government adopted a map that ensured that every current Member of the Legislative Assembly from the premier's party had a district to run in for re-election, but in the original map, several had been redistricted.[88] However, in the 2007 provincial election only seven of 20 incumbent Members of the Legislative Assembly were re-elected (seven did not run for re-election), and the government was defeated.

Chile

The military government which ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990 was ousted in a national plebiscite in October 1988. Opponents of General Augusto Pinochet voted NO to remove him from power and to trigger democratic elections, while supporters (mostly from the right-wing) voted YES to keep him in office for another eight years.

Five months prior to the plebiscite, the regime published a law regulating future elections and referendums, but the configuration of electoral districts and the manner in which National Congress seats would be awarded were only added to the law seven months after the referendum.[89][90]

For the Chamber of Deputies (lower house), 60 districts were drawn by grouping (mostly) neighboring communes (the smallest administrative subdivision in the country) within the same region (the largest). It was established that two deputies would be elected per district, with the most voted coalition needing to outpoll its closest rival by a margin of more than 2-to-1 to take both seats. The results of the 1988 plebiscite show that neither the "NO" side nor the "YES" side outpolled the other by said margin in any of the newly established districts. They also showed that the vote/seat ratio was lower in districts which supported the "YES" side and higher in those where the "NO" was strongest.[91][92] In spite of this, at the 1989 parliamentary election, the center-left opposition was able to capture both seats (the so-called doblaje) in twelve out of 60 districts, winning control of 60% of the Chamber.

Senate constituencies were created by grouping all lower-chamber districts in a region, or by dividing a region into two constituencies of contiguous lower-chamber districts. The 1980 Constitution allocated a number of seats to appointed senators, making it harder for one side to change the Constitution by itself. The opposition won 22 senate seats in the 1989 election, taking both seats in three out of 19 constituencies, controlling 58% of the elected Senate, but only 47% of the full Senate. The unelected senators were eliminated in the 2005 constitutional reforms, but the electoral map has remained largely untouched (two new regions were created in 2007, one of which altered the composition of two senatorial constituencies; the first election to be affected by this minor change took place in 2013).

France

France is one of the few countries to let legislatures redraw the map with no check.[93] In practice, the Parliament of France sets up an executive commission. Districts called arrondissements were used in the Third Republic and under the Fifth Republic they are called circonscriptions. During the Third Republic, some reforms of arrondissements, which were also used for administrative purposes, were largely suspected to have been arranged to favor the kingmaker in the National Assembly, the Radical Party.

The dissolution of Seine and Seine-et-Oise départements by de Gaulle was seen as a case of Gerrymandering to counter communist influence around Paris.[94]

In the modern regime, there were three designs: in 1958 (regime change), 1987 (by Charles Pasqua) and 2010 (by Alain Marleix), three times by conservative governments. Pasqua's drawing was known to have been particularly good at gerrymandering, resulting in 80% of the seats with 58% of the vote in 1993, and forcing Socialists in the 1997 snap election to enact multiple pacts with smaller parties in order to win again, this time as a coalition. In 2010, the Sarkozy government created 12 districts for expats.

The Constitutional council was called twice by the opposition to decide about gerrymandering, but it never considered partisan disproportions. However, it forced the Marleix committee to respect an 80–120% population ratio, ending a tradition dating back to the Revolution in which départements, however small in population, would send at least two MPs.

Germany

When the electoral districts in Germany were redrawn in 2000, the ruling center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) was accused of gerrymandering to marginalize the left-wing Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS). The SPD combined traditional PDS strongholds in the former East Berlin with new districts made up of more populous areas of the former West Berlin, where the PDS had very limited following.

After having won four seats in Berlin in the 1998 national election, the PDS was able to retain only two seats altogether in the 2002 elections. Under German electoral law, a political party has to win either more than five percent of the votes or at least three directly elected seats, to qualify for top-up seats under the Additional Member System. The PDS vote fell below five percent thus they failed to qualify for top-up seats and were confined to just two members of the Bundestag, the German federal parliament (elected representatives are always allowed to hold their seats as individuals). Had they won a third constituency, the PDS would have gained at least 25 additional seats, which would have been enough to hold the balance of power in the Bundestag.

In the election of 2005, The Left (successor of the PDS) gained 8.7% of the votes and thus qualified for top-up seats.

The number of Bundestag seats of parties which previously got over 5% of the votes cannot be affected very much by gerrymandering, because seats are awarded to these parties on a proportional basis. However, when a party wins so many districts in any one of the 16 federal states that those seats alone count for more than its proportional share of the vote in that same state does the districting have some influence on larger parties—those extra seats, called "Überhangmandate", remain. In the Bundestag election of 2009, Angela Merkel's CDU/CSU gained 24 such extra seats, while no other party gained any;[95] this skewed the result so much that the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany issued two rulings declaring the existing election laws invalid and requiring the Bundestag to pass a new law limiting such extra seats to no more than 15. In 2013, Germany's Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of Überhangmandate, which from then on have to be added in proportion to the second vote of each party thereby making it impossible that one party can have more seats than earned by the proportionate votes in the election.

Greece

Gerrymandering has been rather common in Greek history since organized parties with national ballots only appeared after the 1926 Constitution. The only case before that was the creation of the Piraeus electoral district in 1906, in order to give the Theotokis party a safe district.

The most infamous case of gerrymandering was in the 1956 election. While in previous elections the districts were based on the prefecture level (νομός), for 1956 the country was split in districts of varying sizes, some being the size of prefectures, some the size of sub-prefectures (επαρχία) and others somewhere in between. In small districts the winning party would take all seats, in intermediate size, it would take most and there was proportional representation in the largest districts. The districts were created in such a way that small districts were those that traditionally voted for the right while large districts were those that voted against the right.

This system has become known as the three-phase (τριφασικό) system or the baklava system (because, as baklava is split into full pieces and corner pieces, the country was also split into disproportionate pieces). The opposition, being composed of the center and the left, formed a coalition with the sole intent of changing the electoral law and then calling new elections. Even though the centrist and leftist opposition won the popular vote (1,620,007 votes against 1,594,992), the right-wing ERE won the majority of seats (165 to 135) and was to lead the country for the next two years.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, functional constituencies are demarcated by the government and defined in statutes,[96] making them prone to gerrymandering. The functional constituency for the information technology sector was particular criticized for gerrymandering and voteplanting.[97]

There are also gerrymandering concerns in the constituencies of district councils.[98]

Hungary

In 2011, Fidesz politician János Lázár has proposed a redesign to Hungarian voting districts; considering the territorial results of previous elections, this redesign would favor right-wing politics according to the opposition.[99][100] Since then, the law has been passed by the Fidesz-majority National Assembly.[101] By the political think tanks and media close to the opposition, it took twice as many votes to gain a seat in some election districts as in some others. However, their findings are controversial.[102] Gerrymandering was shown for 2018 election results.[103]

Ireland

Until the 1980s Dáil boundaries in Ireland were drawn not by an independent commission but by government ministers. Successive arrangements by governments of all political characters have been attacked as gerrymandering. Ireland uses the single transferable vote, and as well as the actual boundaries drawn, the main tool of gerrymandering has been the number of seats per constituency used, with three-seat constituencies normally benefiting the strongest parties in an area, whereas four-seat constituencies normally help smaller parties.

In 1947 the rapid rise of new party Clann na Poblachta threatened the position of the governing party Fianna Fáil. The government of Éamon de Valera introduced the Electoral (Amendment) Act 1947, which increased the size of the Dáil from 138 to 147 and increased the number of three-seat constituencies from fifteen to twenty-two. The result was described by the journalist and historian Tim Pat Coogan as "a blatant attempt at gerrymander which no Six County Unionist could have bettered."[104] The following February the 1948 general election was held and Clann na Poblachta secured ten seats instead of the nineteen they would have received proportional to their vote.[104]

In the mid-1970s, the Minister for Local Government, James Tully, attempted to arrange the constituencies to ensure that the governing Fine Gael–Labour Party National Coalition would win a parliamentary majority. The Electoral (Amendment) Act 1974 was planned as a major reversal of previous gerrymandering by Fianna Fáil (then in opposition). Tully ensured that there were as many as possible three-seat constituencies where the governing parties were strong, in the expectation that the governing parties would each win a seat in many constituencies, relegating Fianna Fáil to one out of three.

In areas where the governing parties were weak, four-seat constituencies were used so that the governing parties had a strong chance of still winning two. The election results created substantial change, as there was a larger than expected collapse in the vote. Fianna Fáil won a landslide victory in the 1977 Irish general election, two out of three seats in many cases, relegating the National Coalition parties to fight for the last seat. Consequently, the term "Tullymandering" was used to describe the phenomenon of a failed attempt at gerrymandering.

India

Gerrymandering in India was claimed,[105][106] contributing to BJP party winning 55% of all seats with only 37% of all votes in India's lower house.

Italy

A hypothesis of gerrymandering was theorized by constituencies drawn by the electoral act of 2017, so-called Rosatellum.[107]

Kuwait

From the years 1981 until 2005, Kuwait was divided into 25 electoral districts in order to over-represent the government's supporters (the 'tribes').[108] In July 2005, a new law for electoral reforms was approved which prevented electoral gerrymandering by cutting the number of electoral districts from 25 to 5. The government of Kuwait found that 5 electoral districts resulted in a powerful parliament with the majority representing the opposition. A new law was crafted by the government of Kuwait and signed by the Amir to gerrymander the districts to 10 allowing the government's supporters to regain the majority.[109]

Malaysia

The practice of gerrymandering has been around in the country since its independence in 1957. The ruling coalition at that time, Barisan Nasional (BN; English: "National Front"), has been accused of controlling the election commission by revising the boundaries of constituencies. For example, during the 13th General Election in 2013, Barisan Nasional won 60% of the seats in the Malaysian Parliament despite only receiving 47% of the popular vote.[110] Malapportionment has also been used at least since 1974, when it was observed that in one state alone (Perak), the parliamentary constituency with the most voters had more than ten times as many voters as the one with the fewest voters.[111] These practices finally failed BN in the 14th General Election on 9 May 2018, when the opposing Pakatan Harapan (PH; English: "Alliance of Hope") won despite perceived efforts of gerrymandering and malapportionment from the incumbent.[112]

Malta

The Labour Party that won in 1981, even though the Nationalist Party got the most votes, did so because of its gerrymandering. A 1987 constitutional amendment prevented that situation from reoccurring.

Nepal

After the restoration of democracy in 1990, Nepali politics has well exercised the practice of gerrymandering with the view to take advantage in the election. It was often practiced by Nepali Congress, which remained in power in most of the time. Learning from this, the reshaping of constituency was done for constituent assembly and the opposition now wins elections.

Philippines

Congressional districts in the Philippines were originally based on an ordinance from the 1987 Constitution, which was created by the Constitutional Commission, which was ultimately based on legislative districts as they were drawn in 1907. The same constitution gave Congress of the Philippines the power to legislate new districts, either through a national redistricting bill or piecemeal redistricting per province or city. Congress has never passed a national redistricting bill since the approval of the 1987 constitution, while it has incrementally created 34 new districts, out of the 200 originally created in 1987.

This allows Congress to create new districts once a place reaches 250,000 inhabitants, the minimum required for its creation. With this, local dynasties, through congressmen, can exert influence in the district-making process by creating bills carving new districts from old ones. In time, as the population of the Philippines increases, these districts, or groups of it, will be the basis of carving new provinces out of existing ones.

An example was in Camarines Sur, where two districts were divided into three districts which allegedly favors the Andaya and the Arroyo families; it caused Rolando Andaya and Dato Arroyo, who would have otherwise run against each other, run in separate districts, with one district allegedly not even surpassing the 250,000-population minimum.[113] The Supreme Court later ruled that the 250,000 population minimum does not apply to an additional district in a province.[114] The resulting splits would later be the cause of another gerrymander, where the province would be split into a new province called Nueva Camarines; the bill was defeated in the Senate in 2013.[115]

Singapore

In recent decades, critics have accused the ruling People's Action Party (PAP) of unfair electoral practices to maintain significant majorities in the Parliament of Singapore. Among the complaints are that the government uses gerrymandering.[116] The Elections Department was established as part of the executive branch under the Prime Minister of Singapore, rather than as an independent body.[117] Critics have accused it of giving the ruling party the power to decide polling districts and polling sites through electoral engineering, based on poll results in previous elections.[118]

Members of opposition parties claim that the Group Representation Constituency system is "synonymous to gerrymandering", pointing out examples of Cheng San GRC and Eunos GRC which were dissolved by the Elections Department with voters redistributed to other constituencies after opposition parties gained ground in elections.[119]

South Africa

The landmark 1948 general election was influenced by provisions of the Constitution granting rural areas more constituencies in Parliament than urban areas. Thus the white-supremacist National Party won a plurality against the more moderate United Party despite receiving fewer votes and implemented apartheid.[120][121]

Spain

Until the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931, Spain used both single-member and multi-member constituencies in general elections. Multi-member constituencies were only used in some big cities. Some gerrymandering examples included the districts of Vilademuls or Torroella de Montgrí in Catalonia. These districts were created in order to prevent the Federal Democratic Republican Party to win a seat in Figueres or La Bisbal and to secure a seat to the dynastic parties. Since 1931, the constituency boundaries match the province boundaries.[122]

After the Francoist dictatorship, during the transition to democracy, these fixed provincial constituencies were reestablished in Section 68.2 of the current 1978 Spanish Constitution, so gerrymandering is impossible in general elections.[42] There are not winner-takes-all elections in Spain except for the tiny territories of Ceuta and Melilla (which only have one representative each); everywhere else the number of representatives assigned to a constituency is proportional to its population and calculated according to a national law, so tampering with under- or over-representation is difficult too.

European, some regional and municipal elections are held under single, at-large multi-member constituencies with proportional representation and gerrymandering is not possible either.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka's new Local Government elections process has been the talking point of gerrymandering since its inception.[123] Even though that talk was more about the ward-level, it is also seen in some local council areas too.[124][125]

Sudan

In the most recent election of 2010, there were numerous examples of gerrymandering throughout the entire country of Sudan. A report from the Rift Valley Institute uncovered violations of Sudan's electoral law, where constituencies were created that were well below and above the required limit. According to Sudan's National Elections Act of 2008, no constituency can have a population that is 15% greater or less than the average constituency size. The Rift Valley Report uncovered a number of constituencies that are in violation of this rule. Examples include constituencies in Jonglei, Warrap, South Darfur, and several other states.[126]

Turkey

Turkey has used gerrymandering in the city of Istanbul in the 2009 municipal elections. Just before the election Istanbul was divided into new districts. Large low income neighborhoods were bundled with the rich neighborhoods to win the municipal elections.[127]

Parliamentary Elections

Prior to the establishment of Home Rule in Northern Ireland, the UK government had installed the single transferable vote (STV) system in Ireland to secure fair elections in terms of proportional representation in its Parliaments. After two elections under that system, in 1929 Stormont changed the electoral system to be the same as the rest of the United Kingdom: a single-member first past the post system. The only exception was for the election of four Stormont MPs to represent the Queen's University of Belfast. Some scholars believe that the boundaries were gerrymandered to under-represent Nationalists.[104] Other geographers and historians, for instance Professor John H. Whyte, disagree.[128][129] They have argued that the electoral boundaries for the Parliament of Northern Ireland were not gerrymandered to a greater level than that produced by any single-winner election system, and that the actual number of Nationalist MPs barely changed under the revised system (it went from 12 to 11 and later went back up to 12). Most observers have acknowledged that the change to a single-winner system was a key factor, however, in stifling the growth of smaller political parties, such as the Northern Ireland Labour Party and Independent Unionists. In the 1967 election, Unionists won 35.5% of the votes and received 60% of the seats, while Nationalists got 27.4% of the votes but received 40% of the seats. This meant that both the Unionist and Nationalist parties were over-represented, while the Northern Ireland Labour Party and Independents (amounting to more than 35% of the votes cast) were severely under-represented.

After Westminster reintroduced direct rule in 1973, it restored the single transferable vote (STV) for elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly in the following year, using the same definitions of constituencies as for the Westminster Parliament. Currently, in Northern Ireland, all elections use STV except those for positions in the Westminster Parliament, which follow the pattern in the rest of the United Kingdom by using "first past the post."

Local authority Elections

Gerrymandering (Irish: Claonroinnt) in local elections was introduced in 1923 by the Leech Commission. This was a one-man commission: Sir John Leech, K.C. was appointed by Dawson Bates, Northern Ireland's Minister of Home Affairs, to redraw Northern Ireland's local government electoral boundaries.[130]: 68 Leech was also chairman of the Advisory Committee who recommended the release or continued detention of the persons that the Northern Irish government was interning without trial at that time.[131] Leech's changes, together with a resultant boycott by the Irish Nationalist community, resulted in Unionists gaining control of Londonderry County Borough Council, Fermanagh and Tyrone County Councils, and also retaking eight rural district councils. These county councils, and most of the district councils, remained under Unionist control, despite the majority of their population being Catholic, until the United Kingdom government imposed Direct Rule in 1972.[132][133]

Leech's new electoral boundaries for the 1924 Londonderry County Borough Council election reduced the number of wards from four to three, only one of which would have a Nationalist majority. This resulted in election of a Unionist council in every election, until the County Borough Council's replacement in 1969 by the unelected Londonderry Development Commission, in a city where Nationalists had a large majority and had won previous elections.[134][128]

Some critics and supporters spoke at the time of "A Protestant Parliament for a Protestant People".[135] This passed also into local government, where appointments and jobs were given to the supporters of the elected majorities.[133] Stephen Gwynn had noted as early as 1911 that since the introduction of the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898:

In Armagh there are 68,000 Protestants, 56,000 Catholics. The County Council has twenty-two Protestants and eight Catholics. In Tyrone, Catholics are a majority of the population, 82,000 against 68,000; but the electoral districts have been so arranged that Unionists return sixteen as against thirteen Nationalists (one a Protestant). This Council gives to the Unionists two to one majority on its Committees, and out of fifty-two officials employs only five Catholics. In Antrim, which has the largest Protestant majority (196,000 to 40,000), twenty-six Unionists and three Catholics are returned. Sixty officers out of sixty-five are good Unionists and Protestants.[136]

Initially Leech drew the boundaries, but from the 1920s to the 1940s the province-wide government redrew them to reinforce the gerrymander.[128]: 1(c) [137]

United Kingdom – Boundary review

The number of electors in a United Kingdom constituency can vary considerably, with the smallest constituency currently (2017 electoral register) having fewer than a fifth of the electors of the largest (Scotland's Na h-Eileanan an Iar (21,769 constituents) and Orkney and Shetland (34,552), compared to England's North West Cambridgeshire (93,223) and Isle of Wight (110,697)). This variation has resulted from:

- Scotland and Wales being favoured in the Westminster Parliament with deliberately smaller electoral quotas (average electors per constituency) than those in England and Northern Ireland. This inequality was initiated by the House of Commons (Redistribution of Seats) Act 1958, which eliminated the previous common electoral quota for the whole United Kingdom and replaced it with four separate national quotas for the respective Boundaries commissions to work to: England 69,534; Northern Ireland 67,145, Wales 58,383 and in Scotland only 54,741 electors.

- Current rules historically favouring geographically "natural" constituencies, this continues to give proportionally greater representation to Wales and Scotland.

- Population migrations, due to white flight and deindustrialization tending to decrease the number of electors in inner-city districts.

Under the Sixth Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies, the Coalition government planned to review and redraw the parliamentary constituency boundaries for the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. The review and redistricting was to be carried out by the four UK boundary commissions to produce a reduction from 650 to 600 seats, and more uniform sizes, such that a constituency was to have no fewer than 70,583 and no more than 80,473 electors. The process was intended to address historic malapportionment, and be complete by 2015.[138][139] Preliminary reports suggesting the areas set to lose the fewest seats historically tended to vote Conservative, while other less populous and deindustrialized regions, such as Wales, which would lose a larger proportion of its seats, tending to have more Labour and Liberal Democrat voters, partially correcting the existing malapportionment. An opposition (Labour) motion to suspend the review until after the next general election was tabled in the House of Lords and a vote called in the United Kingdom House of Commons, in January 2013. The motion was passed with the help of the Liberal Democrats, going back on an election pledge. As of October 2016, a new review is in progress and a draft of the new boundaries has been published.

United States

.gif)

The United States, among the first countries with an elected representative government, was the source of the term gerrymander as stated above.

The practice of gerrymandering the borders of new states continued past the American Civil War and into the late 19th century. The Republican Party used its control of Congress to secure the admission of more states in territories friendly to their party—the admission of Dakota Territory as two states instead of one being a notable example. By the rules for representation in the Electoral College, each new state carried at least three electoral votes regardless of its population.[140]

All redistricting in the United States has been contentious because it has been controlled by political parties vying for power. As a consequence of the decennial census required by the United States Constitution, districts for members of the House of Representatives typically need to be redrawn whenever the number of members in a state changes. In many states, state legislatures redraw boundaries for state legislative districts at the same time.

State legislatures have used gerrymandering along racial lines both to decrease and increase minority representation in state governments and congressional delegations. In Ohio, a conversation between Republican officials was recorded that demonstrated that redistricting was being done to aid their political candidates. Furthermore, the discussions assessed the race of voters as a factor in redistricting, on the premise that African-Americans tend to back Democratic Party candidates. Republicans removed approximately 13,000 African-American voters from the district of Jim Raussen, a Republican candidate for the House of Representatives, in an apparent attempt to tip the scales in what was once a competitive district for Democratic candidates.[141]

With the Civil Rights Movement and passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, federal enforcement and protections of suffrage for all citizens were enacted. Gerrymandering for the purpose of reducing the political influence of a racial or ethnic minority group was prohibited. After the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, some states created "majority-minority" districts to enhance minority voting strength. This practice, also called "affirmative gerrymandering", was supposed to redress historic discrimination and ensure that ethnic minorities would gain some seats and representation in government. In some states, bipartisan gerrymandering is the norm. State legislators from both parties sometimes agree to draw congressional district boundaries in a way that ensures the re-election of most or all incumbent representatives from both parties.[142]