Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the New-York Tribune. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York, and was the unsuccessful candidate of the new Liberal Republican Party in the 1872 presidential election against incumbent President Ulysses S. Grant, who won by a landslide.

Horace Greeley | |

|---|---|

Greeley c. 1860s | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 6th district | |

| In office December 4, 1848 – March 3, 1849 | |

| Preceded by | David S. Jackson |

| Succeeded by | James Brooks |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 3, 1811 Amherst, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | November 29, 1872 (aged 61) Pleasantville, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Green-Wood Cemetery |

| Political party | Whig (before 1854) Republican (1854–1872) Liberal Republican (1872) |

| Spouse | Mary Cheney

(m. 1836; died 1872) |

| Signature | |

Greeley was born to a poor family in Amherst, New Hampshire. He was apprenticed to a printer in Vermont and went to New York City in 1831 to seek his fortune. He wrote for or edited several publications and involved himself in Whig Party politics, taking a significant part in William Henry Harrison's successful 1840 presidential campaign. The following year, he founded the Tribune, which became the highest-circulating newspaper in the country through weekly editions sent by mail. Among many other issues, he urged the settlement of the American Old West, which he saw as a land of opportunity for the young and the unemployed. He popularized the slogan "Go West, young man, and grow up with the country."[lower-alpha 1] He endlessly promoted utopian reforms such as socialism, vegetarianism, agrarianism, feminism, and temperance while hiring the best talent he could find.

Greeley's alliance with William H. Seward and Thurlow Weed led to him serving three months in the House of Representatives, where he angered many by investigating Congress in his newspaper. In 1854, he helped found and may have named the Republican Party. Republican newspapers across the nation regularly reprinted his editorials. During the Civil War, he mostly supported Abraham Lincoln, though he urged the president to commit to the end of slavery before Lincoln was willing to do so. After Lincoln's assassination, he supported the Radical Republicans in opposition to President Andrew Johnson. He broke with the Radicals and with Republican President Ulysses Grant because of corruption, and Greeley's view that Reconstruction era policies were no longer needed.

Greeley was the new Liberal Republican Party's presidential nominee in 1872. He lost in a landslide despite having the additional support of the Democratic Party. He was devastated by the death of his wife five days before the election and died one month later, before the Electoral College met.

Early life

Greeley was born on February 3, 1811, on a farm about five miles from Amherst, New Hampshire. He could not breathe for the first twenty minutes of his life. It is suggested that this deprivation may have caused him to develop Asperger's syndrome—some of his biographers, such as Mitchell Snay, maintain that this condition would account for his eccentric behaviors in later life.[1] His father's family was of English descent, and his forebears included early settlers of Massachusetts and New Hampshire,[2] while his mother's family descended from Scots-Irish immigrants from the village of Garvagh in County Londonderry who had settled Londonderry, New Hampshire. Some of Greeley's maternal ancestors were present at the siege of Derry during the Williamite War in Ireland in 1689.[3]

Greeley was the son of poor farmers Zaccheus and Mary (Woodburn) Greeley. Zaccheus was not successful, and moved his family several times, as far west as Pennsylvania. Horace attended the local schools and was a brilliant student.[4]

Seeing the boy's intelligence, some neighbors offered to pay Horace's way at Phillips Exeter Academy, but the Greeleys were too proud to accept charity. In 1820, Zaccheus's financial reverses caused him to flee New Hampshire with his family lest he be imprisoned for debt, and settle in Vermont. Even as his father struggled to make a living as a hired hand, Horace Greeley read everything he could—the Greeleys had a neighbor who let Horace use his library. In 1822, Horace ran away from home to become a printer's apprentice, but was told he was too young.[5]

In 1826, at age 15, he was made a printer's apprentice to Amos Bliss, editor of the Northern Spectator, a newspaper in East Poultney, Vermont. There, he learned the mechanics of a printer's job, and acquired a reputation as the town encyclopedia, reading his way through the local library.[6] When the paper closed in 1830, the young man went west to join his family, living near Erie, Pennsylvania. He remained there only briefly, going from town to town seeking newspaper employment, and was hired by the Erie Gazette. Although ambitious for greater things, he remained until 1831 to help support his father. While there, he became a Universalist, breaking from his Congregationalist upbringing.[7]

First efforts at publishing

In late 1831, Greeley went to New York City to seek his fortune. There were many young printers in New York who had likewise come to the metropolis, and he could only find short-term work.[8] In 1832, Greeley worked as an employee of the publication Spirit of the Times.[9] He built his resources and set up a print shop in that year. In 1833, he tried his hand with Horatio D. Sheppard at editing a daily newspaper, the New York Morning Post, which was not a success. Despite this failure and its attendant financial loss, Greeley published the thrice-weekly Constitutionalist, which mostly printed lottery results.[10]

On March 22, 1834, he published the first issue of The New-Yorker in partnership with Jonas Winchester.[9] It was less expensive than other literary magazines of the time and published both contemporary ditties and political commentary. Circulation reached 9,000, then a sizable number, yet it was ill-managed and eventually fell victim to the economic Panic of 1837.[11] He also published the campaign newssheet of the new Whig Party in New York for the 1834 campaign, and came to believe in its positions, including free markets with government assistance in developing the nation.[12]

Soon after his move to New York City, Greeley met Mary Young Cheney. Both were living at a boarding house run on the diet principles of Sylvester Graham, eschewing meat, alcohol, coffee, tea, and spices, as well as abstaining from the use of tobacco. Greeley was subscribing to Graham's principles at the time, and to the end of his life rarely ate meat. Mary Cheney, a schoolteacher, moved to North Carolina to take a teaching job in 1835. They were married in Warrenton, North Carolina, on July 5, 1836, and an announcement duly appeared in The New-Yorker eleven days later. Greeley had stopped over in Washington, D.C., on his way south to observe Congress. He took no honeymoon with his new wife, returning to work while his wife took up a teaching job in New York City.[13]

One of the positions taken by The New-Yorker was that the unemployed of the cities should seek lives in the developing American West (in the 1830s, the West encompassed today's Midwestern states). The harsh winter of 1836–1837 and the financial crisis that developed soon after made many New Yorkers homeless and destitute. In his journal, Greeley urged new immigrants to buy guide books on the West, and Congress to make public lands available for purchase at cheap rates to settlers. He told his readers, "Fly, scatter through the country, go to the Great West, anything rather than remain here ... the West is the true destination."[14] In 1838, he advised "any young man" about to start in the world, "Go to the West: there your capabilities are sure to be appreciated and your energy and industry rewarded."[lower-alpha 1][15]

In 1838, Greeley met Albany editor Thurlow Weed. Weed spoke for a liberal faction of the Whigs in his newspaper the Albany Evening Journal. He hired Greeley as editor of the state Whig newspaper for the upcoming campaign. The newspaper, the Jeffersonian, premiered in February 1838 and helped elect the Whig candidate for governor, William H. Seward.[11] In 1839, Greeley worked for several journals, and took a month-long break to go as far west as Detroit.[16]

Greeley was deeply involved in the campaign of the Whig candidate for president in 1840, William Henry Harrison. He published the major Whig periodical the Log Cabin, and also wrote many of the pro-Harrison songs that marked the campaign. These songs were sung at mass meetings, many organized and led by Greeley. According to biographer Robert C. Williams, "Greeley's lyrics swept the country and roused Whig voters to action."[17] Funds raised by Weed helped distribute the Log Cabin widely. Harrison and his running mate John Tyler were easily elected.[18]

Editor of the Tribune

Early years (1841–1848)

By the end of the 1840 campaign, the Log Cabin's circulation had risen to 80,000 and Greeley decided to establish a daily newspaper, the New-York Tribune.[19] At the time, New York had many newspapers, dominated by James Gordon Bennett's New York Herald, which with a circulation of about 55,000 had more readers than its combined competition. As technology advanced, it became cheaper and easier to publish a newspaper, and the daily press came to dominate the weekly, which had once been the more common format for news periodicals. Greeley borrowed money from friends to get started, and published the first issue of the Tribune on April 10, 1841—the day of a memorial parade in New York for President Harrison, who had died after a month in office and been replaced by Vice President Tyler.[20]

In the first issue, Greeley promised that his newspaper would be a "new morning Journal of Politics, Literature, and General Intelligence".[20] New Yorkers were not initially receptive; the first week's receipts were $92 and expenses $525.[20] The paper was sold for a cent a copy by newsboys who purchased bundles of papers at a discount. The price of advertising was initially four cents a line but was quickly raised to six cents. Through the 1840s, the Tribune was four pages, that is, a single sheet folded. It initially had 600 subscribers and 5,000 copies were sold of the first issue.[21]

In the early days, Greeley's chief assistant was Henry J. Raymond, who a decade later founded The New York Times. To place the Tribune on a sound financial footing, Greeley sold a half-interest in it to attorney Thomas McElrath (1807–1888), who became publisher of the Tribune (Greeley was editor) and ran the business side. Politically, the Tribune backed Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, who had unsuccessfully sought the presidential nomination that fell to Harrison, and supported Clay's American System for development of the country. Greeley was one of the first newspaper editors to have a full-time correspondent in Washington, an innovation quickly followed by his rivals.[20] Part of Greeley's strategy was to make the Tribune a newspaper of national scope, not merely local.[22] One factor in establishing the paper nationally was the Weekly Tribune, created in September 1841 when the Log Cabin and The New-Yorker were merged. With an initial subscription price of $2 a year,[23] this was sent to many across the United States by mail and was especially popular in the Midwest.[24] In December 1841, Greeley was offered the editorship of the national Whig newspaper, the Madisonian. He demanded full control, and declined when not given it.[25]

Greeley, in his paper, initially supported the Whig program.[26] As divisions between Clay and President Tyler became apparent, he supported the Kentucky senator and looked to a Clay nomination for president in 1844.[25] However, when Clay was nominated by the Whigs, he was defeated by the Democrat, former Tennessee governor James K. Polk, though Greeley worked hard on Clay's behalf.[27] Greeley had taken positions in opposition to slavery as editor of The New-Yorker in the late 1830s, opposing the annexation of the slaveholding Republic of Texas to the United States.[28] In the 1840s, Greeley became an increasingly vocal opponent of the expansion of slavery.[26]

Greeley hired Margaret Fuller in 1844 as first literary editor of the Tribune, for which she wrote over 200 articles. She lived with the Greeley family for several years, and when she moved to Italy, he made her a foreign correspondent.[29] He promoted the work of Henry David Thoreau, serving as literary agent and seeing to it that Thoreau's work was published.[30] Ralph Waldo Emerson also benefited from Greeley's promotion.[31] Historian Allan Nevins explained:

The Tribune set a new standard in American journalism by its combination of energy in newsgathering with good taste, high moral standards, and intellectual appeal. Police reports, scandals, dubious medical advertisements, and flippant personalities were barred from its pages; the editorials were vigorous but usually temperate; the political news was the most exact in the city; book reviews and book-extracts were numerous; and as an inveterate lecturer Greeley gave generous space to lectures. The paper appealed to substantial and thoughtful people.[32]

Greeley, who had met his wife at a Graham boarding house, became enthusiastic about other social movements that did not last and promoted them in his paper. He subscribed to the views of Charles Fourier, a French social thinker, then recently deceased, who proposed the establishment of settlements called "phalanxes" with a given number of people from various walks of life, who would function as a corporation and among whose members profits would be shared. Greeley, in addition to promoting Fourierism in the Tribune, was associated with two such settlements, both of which eventually failed, though the town that eventually developed on the site of the one in Pennsylvania was after his death renamed Greeley.[33]

Congressman (1848–1849)

In November 1848, Congressman David S. Jackson, a Democrat, of New York's 6th district was unseated for election fraud. Jackson's term was to expire in March 1849 but, during the 19th century, Congress convened annually in December, making it important to fill the seat. Under the laws then in force, the Whig committee from the Sixth District chose Greeley to run in the special election for the remainder of the term, though they did not select him as their candidate for the seat in the following Congress. The Sixth District, or Sixth Ward as it was commonly called, was mostly Irish-American, and Greeley proclaimed his support for Irish efforts towards independence from the United Kingdom. He easily won the November election and took his seat when Congress convened in December 1848.[34] Greeley's selection was procured by the influence of his ally, Thurlow Weed.[35]

As a congressman for three months, Greeley introduced legislation for a homestead act that would allow settlers who improved land to purchase it at low rates—a fourth of what speculators would pay. He was quickly noticed because he launched a series of attacks on legislative privileges, taking note of which congressmen were missing votes, and questioning the office of House Chaplain. This was enough to make him unpopular. But he outraged his colleagues when on December 22, 1848, the Tribune published evidence that many congressmen had been paid excessive sums as travel allowance. In January 1849, Greeley supported a bill that would have corrected the issue, but it was defeated. He was so disliked, he wrote a friend, that he had "divided the House into two parties—one that would like to see me extinguished and the other that wouldn't be satisfied without a hand in doing it."[36]

Other legislation introduced by Greeley, all of which failed, included attempts to end flogging in the Navy and to ban alcohol from its ships. He tried to change the name of the United States to "Columbia", abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, and increase tariffs.[35] One lasting effect of the term of Congressman Greeley was his friendship with a fellow Whig, serving his only term in the House, Illinois's Abraham Lincoln. Greeley's term ended after March 3, 1849, and he returned to New York and the Tribune, having, according to Williams, "failed to achieve much except notoriety".[37]

Influence (1849–1860)

By the end of the 1840s, Greeley's Tribune was not only solidly established in New York as a daily paper, it was highly influential nationally through its weekly edition, which circulated in rural areas and small towns. Journalist Bayard Taylor deemed its influence in the Midwest second only to that of the Bible. According to Williams, the Tribune could mold public opinion through Greeley's editorials more effectively than could the president. Greeley sharpened those skills over time, laying down what future Secretary of State John Hay, who worked for the Tribune in the 1870s, deemed the "Gospel according to St. Horace".[38]

The Tribune remained a Whig paper, but Greeley took an independent course. In 1848, he had been slow to endorse the Whig presidential nominee, General Zachary Taylor, a Louisianan and hero of the Mexican–American War. Greeley opposed both the war and the expansion of slavery into the new territories seized from Mexico and feared Taylor would support expansion as president. Greeley considered endorsing former President Martin Van Buren, candidate of the Free Soil Party, but finally endorsed Taylor, who was elected; the editor was rewarded for his loyalty with the congressional term.[39] Greeley vacillated on support for the Compromise of 1850, which gave victories to both sides of the slavery issue, before finally opposing it. In the 1852 presidential campaign, he supported the Whig candidate, General Winfield Scott, but savaged the Whig platform for its support of the Compromise. "We defy it, execrate it, spit upon it."[40] Such party divisions contributed to Scott's defeat by former New Hampshire senator Franklin Pierce.[41]

In 1853, with the party increasingly divided over the slavery issue, Greeley printed an editorial disclaiming the paper's identity as Whig and declaring it to be nonpartisan. He was confident that the paper would not suffer financially, trusting in reader loyalty. Some in the party were not sorry to see him go: the Republic, a Whig organ, mocked Greeley and his beliefs: "If a party is to be built up and maintained on Fourierism, Mesmerism, Maine Liquor laws, Spiritual Rappings, Kossuthism, Socialism, Abolitionism, and forty other isms, we have no disposition to mix with any such companions."[42] When, in 1854, Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas introduced his Kansas–Nebraska Bill, allowing residents of each territory to decide whether it would be slave or free, Greeley strongly fought the legislation in his newspaper. After it passed, and the Border War broke out in Kansas Territory, Greeley was part of efforts to send free-state settlers there, and to arm them.[43] In return, proponents of slavery recognized Greeley and the Tribune as adversaries, stopping shipments of the paper to the South and harassing local agents.[44] Nevertheless, by 1858, the Tribune reached 300,000 subscribers through the weekly edition, and it would continue as the foremost American newspaper through the years of the Civil War.[45]

The Kansas–Nebraska Act helped destroy the Whig Party, but a new party with opposition to the spread of slavery at its heart had been under discussion for some years. Beginning in 1853, Greeley participated in the discussions that led to the founding of the Republican Party and may have coined its name.[46] Greeley attended the first New York state Republican Convention in 1854 and was disappointed not to be nominated either for governor or lieutenant governor. The switch in parties coincided with the end of two of his longtime political alliances: in December 1854, Greeley wrote that the political partnership between Weed, William Seward (who was by then senator after serving as governor) and himself was ended "by the withdrawal of the junior partner".[47] Greeley was angered over patronage disputes and felt that Seward was courting the rival The New York Times for support.[48]

In 1853, Greeley purchased a farm in rural Chappaqua, New York, where he experimented with farming techniques.[49] In 1856, he designed and built Rehoboth, one of the first concrete structures in the United States.[50] In 1856, Greeley published a campaign biography by an anonymous author for the first Republican presidential candidate, John C. Frémont.[51]

The Tribune continued to print a wide variety of material. In 1851, its managing editor, Charles A. Dana, recruited Karl Marx as a foreign correspondent in London. Marx collaborated with Friedrich Engels on his work for the Tribune, which continued for over a decade, covering 500 articles. Greeley felt compelled to print, "Mr. Marx has very decided opinions of his own, with some of which we are far from agreeing, but those who do not read his letters are neglecting one of the most instructive sources of information on the great questions of current European politics."[52]

Greeley sponsored a host of reforms, including pacifism and feminism and especially the ideal of the hard-working free laborer. Greeley demanded reforms to make all citizens free and equal. He envisioned virtuous citizens who would eradicate corruption. He talked endlessly about progress, improvement, and freedom, while calling for harmony between labor and capital.[53] Greeley's editorials promoted social democratic reforms and were widely reprinted. They influenced the free-labor ideology of the Whigs and the radical wing of the Republican Party, especially in promoting the free-labor ideology. Before 1848 he sponsored an American version of Fourierist socialist reform. but backed away after the failed revolutions of 1848 in Europe.[54] To promote multiple reforms Greeley hired a roster of writers who later became famous in their own right, including Margaret Fuller,[55] Charles A. Dana, George William Curtis, William Henry Fry, Bayard Taylor, Julius Chambers, and Henry Jarvis Raymond, who later co-founded The New York Times.[56] For many years George Ripley was the staff literary critic.[57] Jane Swisshelm was one of the first women hired by a major newspaper.[58]

In 1859, Greeley traveled across the continent to see the West for himself, to write about it for the Tribune, and to publicize the need for a transcontinental railroad.[59] He also planned to give speeches to promote the Republican Party.[60] In May 1859, he went to Chicago, and then to Lawrence in Kansas Territory, and was unimpressed by the local people. Nevertheless, after speaking before the first ever Kansas Republican Party Convention at Osawatomie, Kansas, Greeley took one of the first stagecoaches to Denver, seeing the town then in course of formation as a mining camp of the Pike's Peak Gold Rush.[59] Sending dispatches back to the Tribune, Greeley took the Overland Trail, reaching Salt Lake City, where he conducted a two-hour interview with the Mormon leader Brigham Young—the first newspaper interview Young had given. Greeley encountered Native Americans and was sympathetic but, like many of his time, deemed Indian culture inferior. In California, he toured widely and gave many addresses.[61]

1860 presidential election

Although he remained on cordial terms with Senator Seward, Greeley never seriously considered supporting him in his bid for the Republican nomination for president. Instead, during the run-up to the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago, he pressed the candidacy of former Missouri representative Edward Bates, an opponent of the spread of slavery who had freed his own slaves. In his newspaper, in speeches, and in conversation, Greeley pushed Bates as a man who could win the North and even make inroads in the South. Nevertheless, when one of the dark horse candidates for the Republican nomination, Abraham Lincoln, came to New York to give an address at Cooper Union, Greeley urged his readers to go hear Lincoln, and was among those who accompanied him to the platform. Greeley thought of Lincoln as a possible nominee for vice president.[62]

Greeley attended the convention as a substitute for Oregon delegate Leander Holmes, who was unable to attend. In Chicago, he promoted Bates but deemed his cause hopeless and felt that Seward would be nominated. In conversations with other delegates, he predicted that, if nominated, Seward could not carry crucial battleground states such as Pennsylvania.[63] Greeley's estrangement from Seward was not widely known, giving the editor more credibility.[64] Greeley (and Seward) biographer Glyndon G. Van Deusen noted that it is uncertain how great a part Greeley played in Seward's defeat by Lincoln—he had little success gaining delegates for Bates. On the first two ballots, Seward led Lincoln, but on the second only by a small margin. After the third ballot, on which Lincoln was nominated, Greeley was seen among the Oregon delegation, a broad smile on his face.[65] According to Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, "it is hard to imagine Lincoln letting Greeley's resentment smolder for years as Seward did".[66]

Seward's forces made Greeley a target of their anger at the senator's defeat. One subscriber cancelled, regretting the three-cent stamp he had to use on the letter; Greeley supplied a replacement. When he was attacked in print, Greeley responded in kind. He launched a campaign against corruption in the New York Legislature, hoping voters would defeat incumbents and the new legislators would elect him to the Senate when Seward's term expired in 1861. (Before 1913, senators were elected by state legislatures.) But his main activity during the campaign of 1860 was boosting Lincoln and denigrating the other presidential candidates. He made it clear that a Republican administration would not interfere with slavery where it already was and denied that Lincoln was in favor of voting rights for African Americans. He kept up the pressure until Lincoln was elected in November.[67]

Lincoln soon let it be known that Seward would be Secretary of State, which meant that he would not be a candidate for re-election to the Senate. Weed wanted William M. Evarts elected in his place, while the anti-Seward forces in New York gathered around Greeley. The crucial battleground was the Republican caucus, as the party held the majority in the legislature. Greeley's forces did not have enough votes to send him to the Senate, but they had enough strength to block Evarts's candidacy. Weed threw his support to Ira Harris, who had already received several votes, and who was chosen by the caucus and elected by the legislature in February 1861. Weed was content to have blocked the editor, and stated that he had "paid the first installment on a large debt to Mr. Greeley".[68]

Civil War

War breaks out

After Lincoln's election, there was talk of secession in the South. The Tribune was initially in favor of peaceful separation, with the South becoming a separate nation. According to an editorial on November 9:

If the Cotton States shall become satisfied that they can do better out of the Union than in it, we insist on letting them go in peace. The right to secede may be a revolutionary one, but it exists nevertheless.... And whenever a considerable section of our Union shall deliberately resolve to go out, we shall resist all coercive measures designed to keep it in. We hope never to live in a republic whereof one section is pinned to the residue by bayonets.[69]

Similar editorials appeared through January 1861, after which Tribune editorials took a hard line on the South, opposing concessions.[70] Williams concludes that "for a brief moment, Horace Greeley had believed that peaceful secession might be a form of freedom preferable to civil war".[71] This brief flirtation with disunion would have consequences for Greeley—it was used against him when he ran for president in 1872.[71]

In the days leading up to Lincoln's inauguration, the Tribune headed its editorial columns each day, in large capital letters: "No compromise!/No concession to traitors!/The Constitution as it is!"[72] Greeley attended the inauguration, sitting close to Senator Douglas, as the Tribune hailed the beginning of Lincoln's presidency. When southern forces attacked Fort Sumter, the Tribune regretted the loss of the fort, but applauded the fact that war to subdue the rebels, who formed the Confederate States of America, would now take place. The paper criticized Lincoln for not being quick to use force.[73]

Through the spring and early summer of 1861, Greeley and the Tribune beat the drum for a Union attack. "On to Richmond", a phrase coined by a Tribune stringer, became the watchword of the newspaper as Greeley urged the occupation of the rebel capital of Richmond before the Confederate Congress could meet on July 20. In part because of the public pressure, in mid July Lincoln sent the half-trained Union Army into the field at the First Battle of Manassas, where it was soundly beaten. The defeat threw Greeley into despair, and he may have suffered a nervous breakdown.[74]

"The Prayer of Twenty Millions"

Restored to health by two weeks at the farm he had purchased in Chappaqua, Greeley returned to the Tribune and a policy of general backing of the Lincoln administration, even having kind words to say about Secretary Seward, his old foe. He was supportive even during the military defeats of the first year of the war. Late in 1861, he proposed to Lincoln through an intermediary that the president provide him with advance information as to its policies, in exchange for friendly coverage in the Tribune. Lincoln eagerly accepted, "having him firmly behind me will be as helpful to me as an army of one hundred thousand men."[75]

By early 1862, however, Greeley was again sometimes critical of the administration, frustrated by the failure to win decisive military victories, and perturbed at the president's slowness to commit to the emancipation of the slaves once the Confederacy was defeated, something the Tribune was urging in its editorials. This was a change in Greeley's thinking which began after First Manassas, a shift from preservation of the Union being the primary war purpose to wanting the war to end slavery. By March, the only action against slavery that Lincoln had backed was a proposal for compensated emancipation in the border states that had remained loyal to the Union, though he signed legislation abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia.[76] Lincoln supposedly asked a Tribune correspondent, "What in the world is the matter with Uncle Horace? Why can't he restrain himself and wait a little while?"[77]

Greeley's prodding of Lincoln culminated in a letter to him on August 19, 1862, reprinted on the following day in the Tribune as "The Prayer of Twenty Millions". By this time, Lincoln had informed his Cabinet of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation he had composed, and Greeley was told of it the same day the prayer was printed. In his letter, Greeley demanded action on emancipation and strict enforcement of the Confiscation Acts. Lincoln must "fight slavery with liberty", and not fight "wolves with the devices of a sheep."[78]

Lincoln's reply would become famous, much more so than the prayer that provoked it.[79] "My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.[80] What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union."[81] Lincoln's statement angered abolitionists; William Seward's wife Frances complained to her husband that Lincoln had made it seem "that the mere keeping together a number of states is more important than human freedom."[81] Greeley felt Lincoln had not truly answered him, "but I'll forgive him everything if he'll issue the proclamation".[79] When Lincoln did, on September 22, Greeley hailed the Emancipation Proclamation as a "great boon of freedom". According to Williams, "Lincoln's war for Union was now also Greeley's war for emancipation."[82]

Draft riots and peace efforts

After the Union victory at Gettysburg in early July 1863, the Tribune wrote that the rebellion would be quickly "stamped out".[83] A week after the battle, the New York City draft riots erupted. Greeley and the Tribune were generally supportive of conscription, though feeling that the rich should not be allowed to evade it by hiring substitutes. Support for the draft made them targets of the mob, and the Tribune Building was surrounded, and at least once invaded. Greeley secured arms from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and 150 soldiers kept the building secure. Mary Greeley and her children were at the farm in Chappaqua; a mob threatened them but dispersed without doing harm.[84]

In August 1863, Greeley was requested by a firm of Hartford publishers to write a history of the war. Greeley agreed, and over the next eight months he penned a 600-page volume, which would be the first of two, entitled The American Conflict.[85] The books were very successful, selling a total of 225,000 copies by 1870, a large sale for the time.[86]

Throughout the war, Greeley played with ideas as to how to settle it. In 1862, Greeley had approached the French minister to Washington, Henri Mercier, to discuss a mediated settlement. However, Seward rejected such talks, and the prospect of European intervention receded after the bloody Union victory at Antietam in September 1862.[87] In July 1864, Greeley received word that there were Confederate commissioners in Canada, empowered to offer peace. In fact, the men were in Niagara Falls, Canada, in order to aid Peace Democrats and otherwise undermine the Union war effort. but they played along when Greeley journeyed to Niagara Falls, at Lincoln's request. The president was willing to consider any deal that included reunion and emancipation. The Confederates had no credentials and were unwilling to accompany Greeley to Washington under safe conduct. Greeley returned to New York, and the episode, when it became public, embarrassed the administration. Lincoln said nothing publicly concerning Greeley's credulous conduct, but he privately indicated that he had no confidence in him any more.[88]

Greeley did not initially support Lincoln for nomination in 1864, casting about for other candidates. In February, he wrote in the Tribune that Lincoln could not be elected to a second term. Nevertheless, no candidate made a serious challenge to Lincoln, and Lincoln was nominated in June, which the Tribune applauded slightly.[89] In August, fearing a Democratic victory and acceptance of the Confederacy, Greeley engaged in a plot to get a new convention to nominate another candidate, with Lincoln withdrawing. The plot came to nothing. Once Atlanta was taken by Union forces on September 3, Greeley became a fervent supporter of Lincoln. Greeley was gratified by both Lincoln's re-election and continued Union victories.[90]

Reconstruction

As the war drew to a close in April 1865, Greeley and the Tribune urged magnanimity towards the defeated Confederates, arguing that making martyrs of Confederate leaders would only inspire future rebels. This talk of moderation ceased when Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. Many concluded that Lincoln had fallen as the result of a final rebel plot, and the new president, Andrew Johnson, offered $100,000 for the capture of fugitive Confederate president Jefferson Davis. After the rebel leader was caught, Greeley initially advocated that "punishment be meted out in accord with a just verdict".[91]

Through 1866, Greeley editorialized that Davis, who was being held at Fortress Monroe, should either be set free or put on trial. Davis's wife Varina urged Greeley to use his influence to gain her husband's release. In May 1867, a Richmond judge set bail for the former Confederate president at $100,000. Greeley was among those who signed the bail bond, and the two men met briefly at the courthouse. This act resulted in public anger against Greeley in the North. Sales of the second volume of his history (published in 1866) declined sharply.[92] Subscriptions to the Tribune (especially the Weekly Tribune) also dropped off, though they recovered during the 1868 election.[93]

Initially supportive of Andrew Johnson's lenient Reconstruction policies, Greeley soon became disillusioned, as the president's plan allowed the quick formation of state governments without securing suffrage for the freedman. When Congress convened in December 1865, and gradually took control of Reconstruction, he was generally supportive, as Radical Republicans pushed hard for universal male suffrage and civil rights for freedmen. Greeley ran for Congress in 1866 but lost badly. He ran for Senate in the legislative election held in early 1867 but lost to Roscoe Conkling.[94]

As the president and Congress battled, Greeley remained firmly opposed to the president, and when Johnson was impeached in March 1868, Greeley and the Tribune strongly supported his removal, attacking Johnson as "an aching tooth in the national jaw, a screeching infant in a crowded lecture room," and declaring, "There can be no peace or comfort till he is out."[95] Nevertheless, the president was acquitted by the Senate, much to Greeley's disappointment. Also in 1868, Greeley sought the Republican nomination for governor but was frustrated by the Conkling forces. Greeley supported the successful Republican presidential nominee, General Ulysses S. Grant in the 1868 election.[96]

Grant years

In 1868, Whitelaw Reid joined the Tribune 's staff as managing editor.[97] In Reid, Greeley found a reliable second-in-command.[98] Also on the Tribune's staff in the late 1860s was Mark Twain.[99] Henry George sometimes contributed pieces, as did Bret Harte.[100] In 1870, John Hay joined the staff as an editorial writer. Greeley soon pronounced Hay the most brilliant at that craft ever to write for the Tribune.[101]

Greeley maintained his interest in associationism. Beginning in 1869, he was heavily involved in an attempt to found the Union Colony of Colorado, a utopia on the prairie, in a scheme led by Nathan Meeker. The new town of Greeley, Colorado Territory was named after him. He served as treasurer and lent Meeker money to keep the colony afloat. In 1871, Greeley published a book What I Know About Farming, based on his childhood experience and that from his country home in Chappaqua.[102][103]

Greeley continued to seek political office, running for state comptroller in 1869 and the House of Representatives in 1870, losing both times.[104] In 1870, President Grant offered Greeley the post of minister to Santo Domingo (today, the Dominican Republic), which he declined.[105]

Presidential candidate

As had been the case for much of the 19th century, political parties continued to be formed and to vanish after the Civil War. In September 1871, Missouri Senator Carl Schurz formed the Liberal Republican Party, founded on opposition to President Grant, opposition to corruption, and support of civil service reform, lower taxes, and land reform. He gathered around him an eclectic group of supporters whose only real link was their opposition to Grant, whose administration had proved increasingly corrupt (although Grant himself was not corrupt). The party needed a candidate, with a presidential election upcoming. Greeley was one of the best-known Americans, as well as being a perennial candidate for office.[106] He was more minded to consider a run for the Republican nomination, fearing the effect on the Tribune should he bolt the party. Nevertheless, he wanted to be president, as a Republican if possible, and if not, as a Liberal Republican.[107][108]

The Liberal Republican national convention met in Cincinnati in May 1872. Greeley was spoken of as a possible candidate, as was Missouri Governor Benjamin Gratz Brown. Schurz was ineligible, being foreign-born. On the first ballot, Supreme Court Justice David Davis led, but Greeley took a narrow lead on the second ballot. Former minister to Britain Charles Francis Adams then took the lead, but on the sixth ballot, after a "spontaneous" demonstration staged by Reid, Greeley gained the nomination, with Brown as vice presidential candidate.[109]

The Democrats, when they met in Baltimore in July, faced a stark choice: nominate Greeley, long a thorn in their side, or split the anti-Grant vote and go on to certain defeat. They chose the former, and even adopted the Liberal Republican platform, which called for equal rights for African Americans.[110] Greeley resigned as editor of the Tribune for the campaign,[111] and, unusually for the time, embarked on a speaking tour to bring his message to the people. As it was customary for candidates for major office not to actively campaign, he was attacked as a seeker after office.[112] Nevertheless, in late July, Greeley (and others, such as former Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes) thought he would very likely be elected.[113] Greeley campaigned on a platform of intersectional reconciliation, arguing that the war was over and the issue of slavery was resolved. It was time to restore normalcy and end the continuing military occupation of the South.[114]

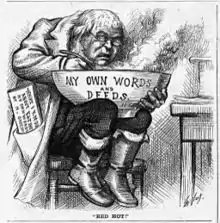

The Republican counterattack was well financed, accusing Greeley of support for everything from treason to the Ku Klux Klan. The anti-Greeley campaign was famously and effectively summed up in the cartoons of Thomas Nast, whom Grant later credited with a major role in his re-election. Nast's cartoons showed Greeley giving bail money for Jefferson Davis, throwing mud on Grant, and shaking hands with John Wilkes Booth across Lincoln's grave. The Crédit Mobilier scandal—corruption in the financing of the Union Pacific Railroad—broke in September, but Greeley was unable to take advantage of the Grant administration's ties to the scandal as he had stock in the railroad himself, and some alleged it had been given to him in exchange for favorable coverage.[115]

Greeley's wife Mary had returned ill from a trip to Europe in late June.[116] Her condition worsened in October, and he effectively broke off campaigning after October 12 to be with her. She died on October 30, plunging him into despair a week before the election.[117] Poor results for the Democrats in those states that had elections for other offices in September and October presaged defeat for Greeley, and so it proved. He received 2,834,125 votes to 3,597,132 for Grant, who secured 286 electors to 66 for Greeley. The editor-turned-candidate won only six states (out of 37): Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Tennessee and Texas.[118]

Final month and death

Greeley resumed the editorship of the Tribune, but quickly learned there was a movement underway to unseat him. He found himself unable to sleep, and after a final visit to the Tribune on November 13 (a week after the election) he remained under medical care. At the recommendation of a family physician, Greeley was sent to Choate House, the asylum of Dr. George Choate at Pleasantville, New York.[119] There, he continued to worsen, and he died on November 29, with his two surviving daughters and Whitelaw Reid at his side.[120]

His death came before the Electoral College balloted. His 66 electoral votes were divided among four others, principally Indiana governor-elect Thomas A. Hendricks and Greeley's vice presidential running mate, Benjamin Gratz Brown.[121]

Although Greeley had requested a simple funeral, his daughters ignored his wishes and arranged a grand affair at the Church of the Divine Paternity, later the Fourth Universalist Society in the City of New York, where Greeley was a member. He is buried in Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery. Among the mourners were old friends, Tribune employees including Reid and Hay, his journalistic rivals, and a broad array of politicians, led by President Grant.[122]

Appraisal

Despite the venom that had been spewed over him in the presidential campaign, Greeley's death was widely mourned. Harper's Weekly, which had printed Nast's cartoons, wrote, "Since the assassination of Mr. Lincoln, the death of no American has been so sincerely deplored as that of Horace Greeley; and its tragical circumstances have given a peculiarly affectionate pathos to all that has been said of him."[123] Henry Ward Beecher wrote in the Christian Union, "when Horace Greeley died, unjust and hard judgment of him died also".[124] Harriet Beecher Stowe noted Greeley's eccentric dress, "That poor white hat! If, alas, it covered many weaknesses, it covered also much strength, much real kindness and benevolence, and much that the world will be better for".[124]

Greeley supported liberal policies towards the fast-growing western regions; he memorably advised the ambitious to "Go West, young man."[125] He hired Karl Marx because of his interest in coverage of working-class society and politics,[126] attacked monopolies of all sorts, and rejected land grants to railroads.[127] Industry would make everyone rich, he insisted, as he promoted high tariffs.[128] He supported vegetarianism, opposed liquor, and paid serious attention to any ism anyone proposed.[129]

Historian Iver Bernstein says:

Greeley was an eclectic and unsystematic thinker, a one-man switch-board for the international cause of "Reform." He committed himself, all at once, to utopian and artisan socialism, to land, sexual, and dietary reform, and, of course, to anti-slavery. Indeed Greeley's great significance in the culture and politics of Civil War-era America stemmed from his attempt to accommodate intellectually the contradictions inherent in the many diverse reform movements of the time.[130]

Greeley's view of freedom was based in the desire that all should have the opportunity to better themselves.[131] According to his biographer, Erik S. Lunde, "a dedicated social reformer deeply sympathetic to the treatment of poor white males, slaves, free blacks, and white women, he still espoused the virtues of self-help and free enterprise".[132] Van Deusen stated: "His genuine human sympathies, his moral fervor, even the exhibitionism that was a part of his makeup, made it inevitable that he should crusade for a better world. He did so with apostolic zeal."[133]

Nevertheless, Greeley's effectiveness as a reformer was undermined by his idiosyncrasies: according to Williams, he "must have looked like an apparition, a man of eccentric habits dressed in an old linen coat that made him look like a farmer who came into town for supplies".[134] Van Deusen wrote, "Greeley's effectiveness as a crusader was limited by some of his traits and characteristics. Culturally deficient, he was to the end ignorant of his own limitations, and this ignorance was a great handicap."[133]

The Tribune remained under that name until 1924, when it merged with the New York Herald to become the New York Herald-Tribune, which was published until 1966.[135] The name survived until 2013, when the International Herald-Tribune became the International New York Times.[136]

The town of Greeley, Colorado is named after Horace Greeley.[137]

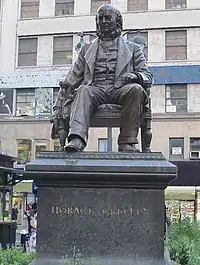

There is a statue of Greeley in City Hall Park in New York, donated by the Tribune Association. Cast in 1890, it was not dedicated until 1916.[138] A second statue of Greeley is located in Greeley Square in Midtown Manhattan.[139] Greeley Square, at Broadway and 33rd Street, was named by the New York City Common Council in a vote after Greeley's death.[140] Van Deusen concluded his biography of Greeley:

More significant still was the service that Greeley performed as a result of his faith in his country and his countrymen, his belief in infinite American progress. For all his faults and shortcomings, Greeley symbolized an America that, though often shortsighted and misled, was never suffocated by the wealth pouring from its farms and furnaces ... For through his faith in the American future, a faith expressed in his ceaseless efforts to make real the promise of America, he inspired others with hope and confidence, making them feel that their dreams also had the substance of realty. It is his faith, and theirs that has given him his place in American history. In that faith he still marches among us, scolding and benevolent, exhorting us to confidence and to victory in the great struggles of our own day.[141]

Notes and references

Explanatory notes

- The origin of the phrase "Go West, young man, and grow up with the country" and its variants is uncertain, though Greeley popularized it and he is closely associated with the phrase. The Tribune alleged that the phrase was "attached to the editor erroneously" and, according to his biographer Williams, Greeley probably did not coin it. There are many tales regarding its origination: minister Josiah Grinnell, founder of Iowa's Grinnell College, claimed to be the young man whom Greeley first told to "go West". See Thomas Fuller, "'Go West, young man!'—An Elusive Slogan." Indiana Magazine of History (2004): 231–242. online See Williams, pp. 40–41

Citations

- Snay, p. 9.

- Williams, p. 6.

- "The Ulster-Scots and New England: Scotch-Irish foundations in the New World" (PDF). Ulster-Scots Agency. p. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- Lunde, p. 26.

- Williams, p. 12.

- Williams, p. 15.

- Williams, pp. 30–33.

- Snay, p. 16.

- Lunde, p. 11.

- Williams, p. 27.

- Tuchinsky, pp. 4–5.

- Williams, pp. 31–32.

- Williams, pp. 37–39.

- Williams, pp. 41–42.

- Williams, p. 43.

- Williams, p. 47.

- Williams, p. 53.

- Williams, pp. 53–54.

- Tuchinsky, p. 5.

- Williams, p. 58.

- Snay, pp. 54–55.

- Lunde, p. 24.

- Snay, p. 55.

- Snay, pp. 11, 23.

- Williams, p. 59.

- Snay, p. 63.

- Snay, pp. 86–87.

- Snay, pp. 39–41.

- Williams, pp. 78–81.

- Williams, p. 82.

- Williams, pp. 81–82.

- Nevins, pp. 528–534.

- Snay, pp. 68–72.

- Williams, p. 114.

- Tuchinsky, p. 145.

- Williams, pp. 114–115.

- Williams, pp. 115–116.

- Williams, p. 61.

- Tuchinsky, pp. 144–145.

- Snay, pp. 110–112.

- Snay, p. 112.

- Tuchinsky, p. 155.

- Snay, pp. 114–115.

- Williams, p. 168.

- Williams, p. 169.

- Williams, p. 175.

- Snay, pp. 116–117.

- Snay, p. 117.

- Lunde ANB.

- Walter J. Gruber and Dorothy W. Gruber (March 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Registration:Rehoboth". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on December 4, 2011. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- Life of Col. Fremont (Greeley and M'Elrath, New York, 1856).

- Williams, pp. 131–135.

- Mitchell Snay, Horace Greeley and the Politics of Reform in Nineteenth-Century America (2011).

- Adam-Max Tuchinsky, "'The Bourgeoisie Will Fall and Fall Forever': The New-York Tribune, the 1848 French Revolution, and American Social Democratic Discourse." Journal of American History 92.2 (2005): 470–497.

- Adam-Max Tuchinsky, "'Her Cause Against Herself': Margaret Fuller, Emersonian Democracy, and the Nineteenth-Century Public Intellectual." American Nineteenth Century History 5.1 (2004): 66–99.

- Sandburg, Carl (1942). Storm Over the Land. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

- Charles Crowe, George Ripley: Transcendentalist and Utopian Socialist (1967)

- Kathleen Endres, "Jane Grey Swisshelm: 19th century journalist and feminist." Journalism History 2.4 (1975): 128.

- Williams, p. 203.

- Van Deusen, p. 230.

- Lunde, pp. 60–65.

- Van Deusen, pp. 231, 241–245.

- Stoddard, pp. 198–199.

- Goodwin, p. 242.

- Hale, pp. 222–223.

- Goodwin, pp. 255–256.

- Van Deusen, pp. 248–253.

- Van Deusen, pp. 256–257.

- Seitz, pp. 190–191.

- Bonner, p. 435.

- Williams, p. 219.

- Stoddard, p. 210.

- Stoddard, pp. 211–212.

- Williams, pp. 220–223.

- Van Deusen, pp. 279–281.

- Van Deusen, pp. 282–285.

- Williams, p. 226.

- Williams, pp. 232–233.

- Williams, p. 233.

- The fact that Lincoln was planning to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation indicates that he had already chosen the third of these options.

- Goodwin, p. 471.

- Williams, p. 234.

- Hale, p. 271.

- Williams, pp. 240–241.

- Van Deusen, p. 301.

- Williams, p. 245.

- Williams, p. 247.

- Van Deusen, pp. 306–309.

- Van Deusen, pp. 303–304.

- Van Deusen, pp. 310–311.

- Stoddard, pp. 231–234.

- Williams, pp. 272–273.

- Van Deusen, pp. 354–355.

- Van Deusen, pp. 342–349.

- Cohen, Adam (1998) [Time, December 21, 1998, Vol. 152, No. 25]. "An impeachment long ago: Andrew Johnson's saga". CNN. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Van Deusen, pp. 368–373.

- Stoddard, p. 270.

- Van Deusen, p. 377.

- Van Deusen, p. 320.

- Hale, pp. 300, 311.

- Taliaferro, pp. 132–133.

- Williams, pp. 284–289.

- Stoddard, p. 266.

- Williams, p. 293.

- Williams, p. 294.

- Williams, pp. 292–293.

- Williams, pp. 295–296.

- Stoddard, pp. 302–303.

- Williams, pp. 296–298.

- Hale, p. 338.

- Seitz, p. 388.

- Stoddard, pp. 309–310.

- Williams, p. 303.

- Stoddard, p. 313.

- Williams, pp. 303–304.

- Hale, pp. 339–340.

- Williams, p. 305.

- Seitz, pp. 390–391.

- Seitz, pp. 398–399.

- Williams, p. 306.

- Seitz, p. 391.

- Hale, pp. 352–353.

- Seitz, p. 403.

- Seitz, p. 404.

- Earle D. Ross,"Horace Greeley and the West." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 20#1 (1933): 63–74. online

- Leo P. Brophy, "Horace Greeley, 'Socialist'". New York History 29.3 (July 1948): 309–317 excerpt.

- James H. Stauss, "The Political Economy of Horace Greeley" Southwestern Social Science Quarterly (1939): 399–408. online

- James M. Lundberg, Horace Greeley: Print, Politics, and the Failure of American Nationhood (2019) p. 154.

- Karen Iacobbo and Michael Iacobbo, Vegetarian America: A History (2004), p. 84.

- Iver Bernstein (1991). The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War. Oxford UP. p. 184. ISBN 9780199923434.

- Williams, p. 314.

- Lunde, Erik S. (February 2000). "Greeley, Horace". American National Biography Online.(subscription required)

- Van Deusen, p. 428.

- Williams, p. 313.

- "Hear Herald-Tribune Folds in New York". Chicago Tribune. August 13, 1966. pp. 2–10.

- Schmemann, Serge (October 14, 2013). "Turning the Page". International Herald Tribune.

- Winders, Gertrude Hecker, "Horace Greeley: Newspaperman," The John Day Company, New York, 1962, page 143.

- "Horace Greeley". NYC Parks. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- "Horace Greeley". NYC Parks. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- Linn, William Alexander (1912). Horace Greeley: Founder and Editor of the New York Tribune. D. Appleton. pp. 258–259. OCLC 732763.

- Van Deusen, p. 430.

Bibliography

- Bonner, Thomas N. (December 1951). "Horace Greeley and the Secession Movement, 1860–1861". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 38 (3): 425–444. doi:10.2307/1889030. JSTOR 1889030.(subscription required)

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2005). Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-82490-1.

- Hale, William Harlan (1950). Horace Greeley: Voice of the People. Harper & Brothers. OCLC 336934.

- Lunde, Erik S. (February 2000). "Greeley, Horace". American National Biography Online. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- Lunde, Erik S. (1981). Horace Greeley. Twayne's United States Authors Series. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-7343-6.

- Nevins, Allan (1931). "Horace Greeley". Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. 7. Scribner's. pp. 528–34. OCLC 4171403.

- Seitz, Don Carlos (1926). Horace Greeley: Founder of The New York Tribune. online edition

- Snay, Mitchell (2011). Horace Greeley and the Politics of Reform in Nineteenth-Century America. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

- Stoddard, Henry Luther (1946). Horace Greeley: Printer, Editor, Crusader. G. P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 1372308.

- Taliaferro, John (2013). All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, from Lincoln to Roosevelt (Kindle ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-9741-4.

- Tuchinsky, Adam (2009). Horace Greeley's New-York Tribune: Civil War–Era Socialism and the Crisis of Free Labor. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4667-2. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt7zfzw.

- Van Deusen, Glyndon G. (1953). Horace Greeley: Nineteenth-Century Reformer. University of Pennsylvania Press. online edition

- Williams, Robert C. (2006). Horace Greeley: Champion of American Freedom. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9402-9., scholarly biography

Books written by Greeley

- The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States of America, 1860–64 Vol. I (1864) Vol. II (1866)

- Essays Designed to Elucidate The Science of Political Economy, While Serving To Explain and Defend The Policy of Protection to Home Industry, As a System of National Cooperation For True Elevation of Labor (1870)

- Recollections of a Busy Life (1868)

- Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859 (1860)

- "Alice and Phebe Cary", in Eminent Women of the Age; Being Narratives of the Lives and Deeds of the Most Prominent Women of the Present Generation (1868), pp. 164–172.

Further reading

- Borchard, Gregory A. Abraham Lincoln and Horace Greeley. Southern Illinois University Press (2011)

- Cross, Coy F., II. Go West Young Man! Horace Greeley's Vision for America. University of New Mexico Press (1995)

- Downey, Matthew T. "Horace Greeley and the Politicians: The Liberal Republican Convention in 1872," The Journal of American History, Vol. 53, No. 4 (March 1967), pp. 727–750, in JSTOR

- Durante, Dianne. Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide. (New York University Press, 2007): discussion of Greeley and the two memorials to him in New York

- Fahrney, Ralph Ray. Horace Greeley and the Tribune in the Civil War (1936) online

- Guarneri, Carl J. Lincoln's Informer: Charles A. Dana and the Inside Story of the Union War. University Press of Kansas (2019)

- Gura, Philip F. "Horace Greeley and the French Connection," in Man's Better Angels: Romantic Reformers and the Coming of the Civil War. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (2017)

- Holzer, Harold. Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion. Simon & Schuster (2014)

- Isely, Jeter Allen. Horace Greeley and the Republican Party, 1853–1861: A Study of the New York Tribune. Princeton University Press (1947)

- Lundberg, James M. Horace Greeley: Print, Politics, and the Failure of American Nationhood. Johns Hopkins University Press (2019) excerpt

- Lunde, Erik S. "The Ambiguity of the National Idea: The Presidential Campaign of 1872" Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism (1978) 5(1): 1–23.

- Maihafer, Harry J. The General and the Journalists: Ulysses S. Grant, Horace Greeley, and Charles Dana. Brassey's, Inc. (1998)

- Mott, Frank Luther. American Journalism: A History, 1690–1960 (1962) passim.

- Parrington, Vernon L. Main Currents in American Thought (1927), II, pp. 247–57 online edition

- Parton, James. The Life of Horace Greeley, Editor of the New-York Tribune (1854) online.

- Potter, David M. "Horace Greeley and Peaceable Secession." Journal of Southern History (1941), vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 145–159, in JSTOR

- Reid, Whitelaw. Horace Greeley (Scribner's Sons, 1879) online.

- Robbins, Roy M. "Horace Greeley: Land Reform and Unemployment, 1837–1862," Agricultural History, VII, 18 (January 1933)

- Rourke, Constance Mayfield. Trumpets of Jubilee: Henry Ward Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lyman Beecher, Horace Greeley, P.T. Barnum (1927)

- Schulze, Suzanne. Horace Greeley: A Bio-Bibliography. Greenwood (1992). 240 pp.

- Slap, Andrew. The Doom of Reconstruction: The Liberal Republicans in the Civil War Era (2010) online

- Taylor, Sally. "Marx and Greeley on Slavery and Labor." Journalism History vol. 6, no. 4 (1979): 103–107

- Weisberger, Bernard A. "Horace Greeley: Reformer as Republican". Civil War History (1977) 23(1): 5–25. online