Hiligaynon language

Hiligaynon, also often referred to as Ilonggo or Binisaya/Bisaya nga Hiniligaynon/Inilonggo, is an Austronesian regional language spoken in the Philippines by about 9.1 million people, predominantly in Western Visayas and Soccsksargen, most of whom belong to the Hiligaynon people.[3] It is the second-most widely spoken language in the Visayas and belongs to the Bisayan languages, and is more distantly related to other Philippine languages.

| Hiligaynon | |

|---|---|

| Ilonggo | |

| Hiniligaynon, Inilonggo | |

| Pronunciation | /hɪlɪˈɡaɪnən/ |

| Native to | Philippines |

| Region | Western Visayas, Soccsksargen, western Negros Oriental, southwestern portion of Masbate, coastal Palawan, some parts of Romblon and a few parts of Northern Mindanao |

| Ethnicity | Hiligaynon |

Native speakers | 7.8 million (2010)[1] 4th most spoken native language in the Philippines.[2] |

Austronesian

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Hiligaynon alphabet) Hiligaynon Braille Historically Baybayin (c. 13th–19th centuries) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | hil |

| ISO 639-3 | hil |

| Glottolog | hili1240 |

Areas where Hiligaynon is spoken in the Philippines | |

It also has one of the largest native language-speaking populations of the Philippines, despite it not being taught and studied formally in schools and universities until 2012.[4] Hiligaynon is given the ISO 639-2 three-letter code hil, but has no ISO 639-1 two-letter code.

Hiligaynon is mainly concentrated in the regions of Western Visayas (Iloilo, Capiz, Guimaras, and Negros Occidental), as well as in South Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat, and North Cotabato in Soccsksargen. It is also spoken in other neighboring provinces, such as Antique and Aklan (also in Western Visayas), Negros Oriental in Central Visayas, Masbate in Bicol Region, Romblon and Palawan in Mimaropa. It is also spoken as a second language by Kinaray-a speakers in Antique, Aklanon/Malaynon speakers in Aklan, Capiznon speakers in Capiz and Cebuano speakers in Negros Oriental.[5] There are approximately 9,300,000 people in and out of the Philippines who are native speakers of Hiligaynon and an additional 5,000,000 capable of speaking it with a substantial degree of proficiency.[6]

Nomenclature

Aside from "Hiligaynon", the language is also referred to as "Ilonggo" (also spelled Ilongo), particularly in Iloilo and Negros Occidental. Many speakers outside Iloilo argue, however, that this is an incorrect usage of the word "Ilonggo". In precise usage, these people opine that "Ilonggo" should be used only in relation to the ethnolinguistic group of native inhabitants of Iloilo and the culture associated with native Hiligaynon speakers in that place, including their language. The disagreement over the usage of "Ilonggo" to refer to the language extends to Philippine language specialists and native laypeople.[7]

Historically, the term Visayan had originally been applied to the people of Panay; however, in terms of language, "Visayan" is more used today to refer to what is also known as Cebuano. As pointed out by H. Otley Beyer and other anthropologists, the term Visayan was first applied only to the people of Panay and to their settlements eastward in the island of Negros (especially its western portion), and northward in the smaller islands, which now compose the province of Romblon. In fact, at the early part of Spanish Colonization in the Philippines, the Spaniards used the term Visayan only for these areas. While the people of Cebu, Bohol and Leyte were for a long time known only as Pintados. The name Visayan was later extended to these other islands because, as several of the early writers state, their languages are closely allied to the Visayan dialect of Panay.[8]

History

Historical evidence from observations of early Spanish explorers in the Archipelago shows that the nomenclature used to refer to this language had its origin among the people of the coasts or people of the Ilawod ("los [naturales] de la playa") in Iloilo, Panay, whom Spanish explorer Miguel de Loarca called Yligueynes [9] (or the more popular term Hiligaynon, also referred to by the Karay-a people as "Siná"). The term Hiligaynon came from the root word ilig ("to go downstream"), referring to a flowing river in Iloilo. In contrast, the "Kinaray-a" has been used by what the Spanish colonizers called Arayas, which may be a Spanish misconception of the Hiligaynon words Iraya or taga-Iraya, or the current and more popular version Karay-a (highlanders - people of Iraya/highlands).[10]

Dialects

Similar to many languages in the Philippines, very little research on dialectology has been done on Hiligaynon. The Standard Hiligaynon, or simply called "Ilonggo," is the dialect that is used in the province of Iloilo, primarily in the northern and eastern portions of the province. It has a more traditional and extensive vocabulary, whereas the Urban Hiligaynon dialect spoken in Metro Iloilo has a more simplified or modern vocabulary. For example, the term for "to wander," "to walk," or "to stroll" in Urban Hiligaynon is lágaw, which is also widely used by most of the Hiligaynon speakers, whereas in Standard Hiligaynon, dayán is more commonly used, which has rarely or never been used by other dialects of the language. Another example, amó iní ("this is it") in Standard Hiligaynon can be simplified in Urban Hiligaynon and become 'mó'ní.

Some of the other widely recognized dialects of the language, aside from the Standard Hiligaynon and Urban Hiligaynon, are Bacolodnon Hiligaynon (Metro Bacolod dialect), Negrense Hiligaynon (provincial Negros Occidental dialect that is composed of three sub-variants: Northern, Central and Southern Negrense Hiligaynon), Guimaras Hiligaynon, and Mindanao Hiligaynon.

Some native speakers also consider Kinaray-a (also known as Hiniraya or Antiqueño) and Capiznon as dialects of Hiligaynon; however, linguists have classified Kinaray-a as a Western Bisayan language, while Capiznon is a Central Bisayan language closely related to Hiligaynon.[11][12]

Phonology

Consonants

| Bilabial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ʔ | |

| Fricative | s | h | ||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | |||||

Consonants [d] and [ɾ] were once allophones but cannot interchange as in other Philippine languages: patawaron (to forgive) [from patawad, forgiveness] but not patawadon, and tagadiín (from where) [from diín, where] but not tagariín.

Vowels

There are four main vowels: /a/, /i ~ ɛ/, /o ~ ʊ/, and /u/. [i] and [ɛ] (both spelled i) are allophones, with [i] in the beginning and middle and sometimes final syllables and [ɛ] in final syllables. The vowels [ʊ] and [o] are also allophones, with [ʊ] always being used when it is the beginning of a syllable, and [o] always used when it ends a syllable.

Writing system

Hiligaynon is written using the Latin script. Until the second half of the 20th century, Hiligaynon was widely written largely following Spanish orthographic conventions. Nowadays there is no officially recognized standard orthography for the language and different writers may follow different conventions. It is common for the newer generation, however, to write the language based on the current orthographic rules of Filipino.

A noticeable feature of the Spanish-influenced orthography absent in those writing following Filipino's orthography is the use of "c" and "qu" in representing /k/ (now replaced with "k" in all instances) and the absence of the letter "w" (formerly used "u" in certain instances).

The core alphabet consists of 20 letters used for expressing consonants and vowels in Hiligaynon, each of which comes in an uppercase and lowercase variety.

Alphabet

| Symbol | A a | B b | K k | D d | E e | G g | H h | I i | L l | M m | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | a | ba | ka | da | e | ga | ha | i | la | ma | |||

| Pronunciation | [a/ə] | [aw] | [aj] | [b] | [k] | [d] | [ɛ/e] | [ɡ] | [h] | [ɪ/i] | [ɪo] | [l] | [m] |

| in context | a | aw/ao | ay | b | k | d | e | g | h | i | iw/io | l | m |

| Symbol | N n | Ng ng | O o | P p | R r | S s | T t | U u | W w | Y y | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | na | nga | o | pa | ra | sa | ta | u | wa | ya | |||

| Pronunciation | [n] | [ŋ] | [ɔ/o] | [oj] | [p] | [r] | [s] | [ʃʲ] | [t] | [ʊ/u] | [w] | [w] | [j] |

| in context | n | ng | o | oy | p | r | s | sy | t | u | ua | w | y |

Additional symbols

The apostrophe ⟨'⟩ and hyphen ⟨-⟩ also appear in Hiligaynon writing, and might be considered separate letters.

The hyphen, in particular, is used medially to indicate the glottal stop san-o ‘when’ gab-e ‘evening; night’. It is also used in reduplicated words: adlaw-adlaw ‘daily, every day’, from adlaw ‘day, sun’. This marking is not used in reduplicated words whose base is not also used independently, as in pispis ‘bird’.

Hyphens are also used in words with successive sounds of /g/ and /ŋ/, to separate the letters with the digraph NG. Like in the word gin-gaan 'was given'; without the hyphen, it would be read as gingaan /gi.ŋaʔan/ as opposed to /gin.gaʔan/.

In addition, some English letters may be used in borrowed words.

Grammar

Determiners

Hiligaynon has three types of case markers: absolutive, ergative, and oblique. These types in turn are divided into personal, that have to do with names of people, and impersonal, that deal with everything else, and further into singular and plural types, though the plural impersonal case markers are just the singular impersonal case markers + mga (a contracted spelling for /maŋa/), a particle used to denote plurality in Hiligaynon.[13]

| Absolutive | Ergative | Oblique | |

|---|---|---|---|

| singular impersonal | ang | sang, sing* | sa |

| plural impersonal | ang mga | sang mga, sing mga* | sa mga |

| singular personal | si | ni | kay |

| plural personal** | sanday | nanday | kanday |

(*)The articles sing and sing mga means the following noun is indefinite, while sang tells of a definite noun, like the use of a in English as opposed to the, however, it is not as common in modern speech, being replaced by sang. It appears in conservative translations of the Bible into Hiligaynon and in traditional or formal speech.

(**)The plural personal case markers are not used very often and not even by all speakers. Again, this is an example of a case marker that has fallen largely into disuse, but is still occasionally used when speaking a more traditional form of Hiligaynon, using fewer Spanish loan words.

The case markers do not determine which noun is the subject and which is the object; rather, the affix of the verb determines this, though the ang-marked noun is always the topic.

| Ang lalaki nagkaon sang tinapay. | ≈ | Ang tinapay ginkaon sang lalaki. |

| "The man ate the bread" | "The bread was eaten by the man" (literal) |

Personal pronouns

| Absolutive | Ergative₁ (Postposed) |

Ergative₂ (Preposed) |

Oblique | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular | ako, ko | nakon, ko | akon | sa akon |

| 2nd person singular | ikaw, ka | nimo, mo | imo | sa imo |

| 3rd person singular | siya | niya | iya | sa iya |

| 1st person plural inclusive | kita | naton, ta | aton | sa aton |

| 1st person plural exclusive | kami | namon | amon | sa amon |

| 2nd person plural | kamo | ninyo | inyo | sa inyo |

| 3rd person plural | sila | nila | ila | sa ila |

Demonstrative pronouns

| Absolutive | Ergative/Oblique | Locative | Existential | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest to speaker (this, here) * | iní | siní | dirí | (y)ári |

| Near to addressee or closely removed from speaker and addressee (that, there) | inâ | sinâ | dirâ | (y)ára' |

| Remote (yon, yonder) | ató | sadtó | didtó | (y)á(d)to |

In addition to this, there are two verbal deictics, karí, meaning come to speaker, and kadto, meaning to go yonder.

Copula

Hiligaynon lacks the marker of sentence inversion "ay" of Tagalog/Filipino or "hay" of Akeanon. Instead sentences in SV form (Filipino: Di karaniwang anyo) are written without any marker or copula.

Examples:

"Si Saxa ay maganda" (Tagalog)

"Si Saxa matahum/ Gwapa si Saxa" (Hiligaynon) = "Saxa is beautiful."

"Saxa is beautiful" (English)

There is no direct translation for the English copula "to be" in Hiligaynon. However, the prefixes mangin- and nangin- may be used to mean will be and became, respectively.

Example:

Manamì mangín manggaránon.

"It is nice to become rich."

The Spanish copula "estar" (to be) has also become a part of the Hiligaynon lexicon. Its meaning and pronunciation have changed compared to its Spanish meaning, however. In Hiligaynon it is pronounced as "istar" and means "to live (in)/location"(Compare with the Hiligaynon word "puyô").

Example:

Nagaistar ako sa tabuk suba

"I live in tabuk suba"

"tabuk suba" translates to "other side of the river" and is also a barangay in Jaro, Iloilo.

Existential

To indicate the existence of an object, the word may is used.

Example:

May

EXIST

idô

dog

(a)ko

1SG

I have a dog.

Hiligaynon linkers

When an adjective modifies a noun, the linker nga links the two.

Example:

Ido nga itom = Black dog

Sometimes, if the linker is preceded by a word that ends in a vowel, glottal stop or the letter N, it becomes acceptable to contract it into -ng, as in Filipino. This is often used to make the words sound more poetic or to reduce the number of syllables. Sometimes the meaning may change as in maayo nga aga and maayong aga. The first meaning: (the) good morning; while the other is the greeting for 'good morning'.

The linker ka is used if a number modifies a noun.

Example:

Anum ka ido

six dogs

Interrogative pronouns

The interrogative pronouns of Hiligaynon are as follows: diin, san-o, sin-o, nga-a, kamusta, ano, and pila

Diin means where.

Example:

Diin ka na subong?

"Where are you now?"

A derivation of diin, tagadiin, is used to inquire the birthplace or hometown of the listener.

Example:

Tagadiin ka?

"Where are you from?"

San-o means when

Example:

San-o inâ?

"When is that?"

Sin-o means who

Example:

Sin-o imo abyan?

"Who is your friend?"

Nga-a means why

Example:

Nga-a indi ka magkadto?

"Why won't you go?"

Kamusta means how, as in "How are you?"

Example:

Kamusta ang tindahan?

"How is the store?"

Ano means what

Example:

Ano ang imo ginabasa?

"What are you reading?"

A derivative of ano, paano, means how, as in "How do I do that?"

Example:

Paano ko makapulî?

"How can I get home?"

A derivative of paano is paanoano an archaic phrase which can be compared with kamusta

Example:

Paanoano ikaw?

"How art thou?"

Pila means how much/how many

Example:

Pila ang gaupod sa imo?

"How many are with you?"

A derivative of pila, ikapila, asks the numerical order of the person, as in, "What place were you born in your family?"(first-born, second-born, etc.) This word is notoriously difficult to translate into English, as English has no equivalent.

Example:

Ikapila ka sa inyo pamilya?

"What place were you born into your family?"

A derivative of pila, tagpila, asks the monetary value of something, as in, "How much is this beef?"

Example:

Tagpila ini nga karne sang baka?

"How much is this beef?"

Focus

As it is essential for sentence structure and meaning, focus is a key concept in Hiligaynon and other Philippine languages. In English, in order to emphasize a part of a sentence, variation in intonation is usually employed – the voice is stronger or louder on the part emphasized. For example:

- The man is stealing rice from the market for his sister.

- The man is stealing rice from the market for his sister.

- The man is stealing rice from the market for his sister.

- The man is stealing rice from the market for his sister.

Furthermore, active and passive grammatical constructions can be used in English to place focus on the actor or object as the subject:

- The man stole the rice. vs. The rice was stolen by the man.

In contrast, sentence focus in Philippine languages is built into the construction by grammatical elements. Focus is marked by verbal affixes and a special particle prior to the noun in focus. Consider the following Hiligaynon translations of the above sentences:

- Nagakawat ang lalaki sang bugas sa tinda para sa iya utod.

- Ginakawat sang lalaki ang bugas sa tinda para sa iya utod.

- Ginakawatan sang lalaki sang bugas ang tinda para sa iya utod.

- Ginakawatan sang lalaki sang bugas sa tinda para sa iya utod.

- (lalaki = man; kawat = to steal; bugas = rice; tinda = market; sibling = utod; kamot = hand)

Summary table

| TRIGGER | ASPECT | MODE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral | Purposive | Durative | Causative | Distributive | Cooperative | Dubitative | |||

| Agent | Goal | Unreal | -on | pag—on | paga—on | pa—on | pang—on | pakig—on | iga—on |

| Real | gin- | gin- | gina- | ginpa- | ginpang- | ginpakig- | ø | ||

| Referent | Unreal | -an | pag—an | paga—an | pa—an | pang—an | pakig—an | iga—an | |

| Real | gin—an | gin—an | gina—an | ginpa—an | ginpang—an | ginpakig—an | ø | ||

| Accessory | Unreal | i- | ipag- | ipaga- | ipa- | ipang- | ipakig- | iga- | |

| Real | gin- | gin- | gina- | ginpa- | ginpang- | ginpakig- | ø | ||

| Actor | Unreal | -um- | mag- | maga- | ø | mang- | makig- | ø | |

| Real | -um- | nag- | naga- | ø | nang- | nakig- | ø | ||

| Patient | Actor | Unreal | maka- | makapag- | makapaga- | makapa- | makapang- | mapapakig- | ø |

| Real | naka- | nakapag- | nakapaga- | nakapa- | nakapang- | napapakig- | ø | ||

| Goal | Unreal | ma- | mapag- | mapaga- | mapa- | mapang- | mapakig- | ø | |

| Real | na- | napag- | napaga- | napa- | napang- | napakig- | ø | ||

Reduplication

Hiligaynon, like other Philippine languages, employs reduplication, the repetition of a root or stem of a word or part of a word for grammatical or semantic purposes. Reduplication in Hiligaynon tends to be limited to roots instead of affixes, as the only inflectional or derivational morpheme that seems to reduplicate is -pa-. Root reduplication suggests 'non-perfectiveness' or 'non-telicity'. Used with nouns, reduplication of roots indicate particulars which are not fully actualized members of their class.[16] Note the following examples.

balay-bálay

house-house

toy-house, playhouse

maestra-maestra

teacher-teacher

make-believe teacher

Reduplication of verbal roots suggests a process lacking a focus or decisive goal. The following examples describe events which have no apparent end, in the sense of lacking purpose or completion. A lack of seriousness may also be implied. Similarly, reduplication can suggest a background process in the midst of a foreground activity, as shown in (5).[17]

Nag-a-

NAG-IMP-

hìbî-híbî

cry-cry

ang

FOC

bátâ.

child

The child has been crying and crying.

Nag-a-

NAG-IMP-

tinlò-tinlò

clean-clean

akó

1SG.FOC

sang

UNFOC

lamésa

table

I'm just cleaning off the table (casually). Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Nag-a-

NAG-IMP-

kàon-káon

eat-eat

gid

just

silá

3PL.FOC

sang

UNFOC

nag-abót

MAG-arrive

ang

FOC

íla

3PL.UNFOC

bisíta.

visitor

They were just eating when their visitor arrived. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

When used with adjectival roots, non-telicity may suggest a gradualness of the quality, such as the comparison in (6). In comparative constructions the final syllables of each occurrence of the reduplicated root are accented. If the stress of the second occurrence is shifted to the first syllable, then the reduplicated root suggests a superlative degree, as in (7). Note that superlatives can also be created through prefixation of pinaka- to the root, as in pinaka-dakô. While non-telicity can suggest augmentation, as shown in (7), it can also indicate diminishment as in shown in (9), in contrast with (8) (note the stress contrast). In (8b), maàyoáyo, accented in the superlative pattern, suggests a trajectory of improvement that has not been fully achieved. In (9b), maàyoayó suggests a trajectory of decline when accented in the comparative pattern. The reduplicated áyo implies sub-optimal situations in both cases; full goodness/wellness is not achieved.[18]

Iní

this.FOC

nga

LINK

kwárto

room

ma-dulùm-dulúm

MA-dark-dark

sang

UNFOC

sa

OBL

sinâ

that.UNFOC

This room is darker than that one. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

|

(7) dakô-dakô big-big bigger |

dakô-dákô big-big (gid) (really) biggest

|

|

(8) Ma-áyo MA-good ang FOC reló. watch The watch is good/functional. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help); |

Ma-àyo-áyo MA-good-good na now ang FOC reló. watch The watch is semi-fixed. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

|

|

(9) Ma-áyo MA-good akó. 1SG.FOC I'm well. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help); |

Ma-àyo-ayó MA-good-good na now akó. 1SG.FOC I'm so so. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

|

Vocabulary

Derived from Spanish

Hiligaynon has a large number of words derived from Spanish including nouns (e.g., santo from santo, "saint"), adjectives (e.g., berde from verde, "green"), prepositions (e.g., antes from antes, "before"), and conjunctions (e.g., pero from pero, "but").

Nouns denoting material items and abstract concepts invented or introduced during the early modern era include barko (barco, "ship"), sapatos (zapatos, "shoes"), kutsilyo (cuchillo, "knife"), kutsara (cuchara, "spoon"), tenedor ("fork"), plato ("plate"), kamiseta (camiseta, "shirt"), and kambiyo (cambio, "change", as in money). Spanish verbs are incorporated into Hiligaynon in their infinitive forms: edukar, kantar, mandar, pasar. The same holds true for other languages such as Cebuano. In contrast, incorporations of Spanish verbs into Tagalog for the most part resemble, though are not necessarily derived from, the vos forms in the imperative: eduká, kantá, mandá, pasá. Notable exceptions include andar, pasyal (from pasear) and sugal (from jugar).

Examples

Numbers

| Number | Hiligaynon |

|---|---|

| 1 | isá |

| 2 | duhá |

| 3 | tátlo |

| 4 | ápat |

| 5 | limá |

| 6 | ánum |

| 7 | pitó |

| 8 | waló |

| 9 | siyám |

| 10 | pulò / napulò |

| 100 | gatós |

| 1,000 | líbo |

| 10,000 | laksâ |

| 1,000,000 | hámbad / ramák |

| First | tig-una / panguná |

| Second | ikaduhá |

| Third | ikatlo / ikatátlo |

| Fourth | ikap-at / ikaápat |

| Fifth | ikalimá |

| Sixth | ikán-um / ikaánum |

| Seventh | ikapitó |

| Eighth | ikawaló |

| Ninth | ikasiyám |

| Tenth | ikapulò |

Days of the week

The names of the days of the week are derived from their Spanish equivalents.

| Day | Native Names | Meaning | Castilian Derived |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunday | Tigburukad | root word: Bukad, open; Starting Day | Domingo |

| Monday | Dumasaon | root word: Dason, next; Next Day | Lunes |

| Tuesday | Dukot-dukot | literal meaning: Busy Day; Busiest Day | Martes |

| Wednesday | Baylo-baylo | root word: Baylo, exchange; Barter or Market Day | Miyerkoles |

| Thursday | Danghos | literal meaning: rush; Rushing of the Work Day | Huwebes |

| Friday | Hingot-hingot | literal meaning: Completing of the Work Day | Biyernes |

| Saturday | Ligid-ligid | root word: Ligid, lay-down to rest; Rest Day | Sábado |

Months of the year

| Month | Native Name | Castilian Derived |

|---|---|---|

| January | Ulalong | Enero |

| February | Dagang Kahoy | Pebrero |

| March | Dagang Bulan | Marso |

| April | Kiling | Abril |

| May | Himabuyan | Mayo |

| June | Kabay | Hunyo |

| July | Hidapdapan | Hulyo |

| August | Lubad-lubad | Agosto |

| September | Kangurulsol | Setiyembre |

| October | Bagyo-bagyo | Oktubre |

| November | Panglot Diyutay | Nobiyembre |

| December | Panglot Dako | Disiyembre |

Quick phrases

| English | Hiligaynon |

|---|---|

| Yes. | Húo. |

| No. | Indî. |

| Thank you. | Salamat. |

| Thank you very much! | Salamat gid./ Madamò gid nga salamat! |

| I'm sorry. | Patawaron mo ako. / Pasayloha 'ko. / Pasensyahon mo ako. / Pasensya na. |

| Help me! | Buligi (a)ko! / Tabangi (a)ko! |

| Delicious! | Namit! |

| Take care(Also used to signify Goodbye) | Halong. |

| Are you angry/scared? | Akig/hadlok ka? |

| Do you feel happy/sad? | Nalipay/Nasubo-an ka? |

| I don't know/I didn't know | Ambot / Wala ko kabalo / Wala ko nabal-an |

| I don't care | Wa-ay ko labot! |

| That's wonderful/marvelous! | Námì-námì ba! / Nami ah! |

| I like this/that! | Nanámìan ko sini/sina! |

| I love you. | Palangga ta ka./Ginahigugma ko ikaw. |

Greetings

| English | Hiligaynon |

|---|---|

| Hello! | Kumusta/Maayong adlaw (lit. Good day) |

| Good morning. | Maayong aga. |

| Good noon. | Maayong ugto/Maayong udto |

| Good afternoon. | Maayong hapon. |

| Good evening. | Maayong gab-i. |

| How are you? | Kamusta ka?/Kamusta ikaw?/Musta na? (Informal) |

| I'm fine. | Maayo man. |

| I am fine, how about you? | Maayo man, ikaw ya? |

| How old are you? | Pila na ang edad (ni)mo? / Ano ang edad mo? / Pila ka tuig ka na? |

| I am 24 years old. | Beinte kwatro anyos na (a)ko./ Duha ka pulo kag apat ka tuig na (a)ko. |

| My name is... | Ang ngalan ko... |

| I am Erman. | Ako si Erman./Si Erman ako. |

| What is your name? | Ano imo ngalan?/ Ano ngalan (ni)mo? |

| Until next time. | Asta sa liwat. |

This/that/what

| English | Hiligaynon |

|---|---|

| What is this/that? | Ano (i)ni/(i)nâ? |

| This is a sheet of paper. | Isa ni ka panid sang papel./Isa ka panid ka papel ini. |

| That is a book. | Libro (i)nâ. |

| What will you do?/What are you going to do? | Ano ang himu-on (ni)mo? / Ano ang buhaton (ni)mo? / Maano ka? |

| What are you doing? | Ano ang ginahimo (ni)mo? / Gaano ka? |

| My female friend | Ang akon babaye nga abyan/miga |

| My male friend | Ang akon lalake nga abyan/migo |

| My girlfriend/boyfriend | Ang akon nubya/nubyo |

Space and Time

| English | Hiligaynon |

|---|---|

| Where are you now? | Diin ka (na) subong? |

| Where shall we go? | Diin (ki)ta makadto? |

| Where are we going? | Diin (ki)ta pakadto? |

| Where are you going? | (Sa) diin ka makadto? |

| We shall go to Iloilo. | Makadto (ki)ta sa Iloilo. |

| We're going to Bacolod. | Makadto kami sa Bacolod. |

| I am going home. | Mapa-uli na ko (sa balay). / (Ma)puli na ko. |

| Where do you live? | Diin ka naga-istar?/Diin ka naga-puyô? |

| Where did you come from? (Where have you just been?) | Diin ka (nag)-halin? |

| Have you been here long? | Dugay ka na di(ri)? |

| (To the) left. | (Sa) wala. |

| (To the) right. | (Sa) tuo. |

| What time is it? | Ano('ng) takna na?/Ano('ng) oras na? |

| It's ten o'clock. | Alas diyes na. |

| What time is it now? | Ano ang oras subong?/Ano oras na? |

Ancient Times of the Day

| Time | Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 06:00 AM | Butlak Adlaw | Day Break |

| 10:00 AM | Tig-ilitlog or Tig-iritlog | Time for chickens to lay eggs |

| 12:00 noon | Udto Adlaw or Ugto Adlaw | Noon Time or midday |

| 02:00 PM | Huyog Adlaw | Early afternoon |

| 04:00 PM | Tigbarahog | Time for feeding the swine |

| 06:00 PM | Sirom | Twilight |

| 08:00 PM | Tingpanyapon or Tig-inyapon | Supper time |

| 10:00 PM | Tigbaranig | Time to lay the banig or sleeping mat |

| 11:00 PM | Unang Pamalò | First cockerel's crow |

| 12:00 midnight | Tungang Gab-i | Midnight |

| 02:00 AM | Ikaduhang Pamalò | Second cockerel's crow |

| 04:00 AM | Ikatatlong Pamalò | Third cockerel's crow |

| 05:00 AM | Tigbulugtaw or Tigburugtaw | Waking up time |

When buying

| English | Hiligaynon |

|---|---|

| May/Can I buy? | Pwede ko ma(g)-bakal? |

| How much is this/that? | Tag-pilá iní/inâ? |

| I'll buy the... | Baklon ko ang... |

| Is this expensive? | Mahal bala (i)ni? |

| Is that cheap? | Barato bala (i)na? |

The Lord's Prayer

Amay namon, nga yara ka sa mga langit

Pagdayawon ang imo ngalan

Umabot sa amon ang imo ginharian

Matuman ang imo boot

Diri sa duta siling sang sa langit

Hatagan mo kami niyan sing kan-on namon

Sa matag-adlaw

Kag patawaron mo kami sa mga sala namon

Siling nga ginapatawad namon ang nakasala sa amon

Kag dili mo kami ipagpadaog sa mga panulay

Hinunuo luwason mo kami sa kalaot

Amen.

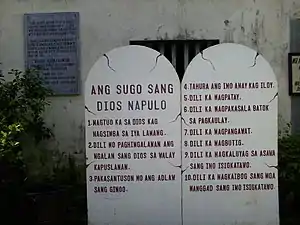

The Ten Commandments

Literal translation as per photo:

- Believe in God and worship only him

- Do not use the name of God without purpose

- Honor the day of the Lord

- Honor your father and mother

- Do not kill

- Do not pretend to be married against virginity (don't commit adultery)

- Do not steal

- Do not lie

- Do not have desire for the wife of your fellow man

- Do not covet the riches of your fellow man

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Ang Kalibutánon nga Pahayag sang mga Kinamaatárung sang Katáwhan)

Ang tanán nga táwo ginbún-ag nga hílway kag may pag-alalangay sa dungóg kag kinamatárong. Silá ginhatágan sing pagpamat-ud kag balatyágon kag nagakadápat nga magbinuligáy sa kahulugan sang pag-inuturáy.

Every person is born free and equal with honor and rights. They are given reason and conscience and they must always trust each other for the spirit of brotherhood.

Notable Hiligaynon writers

- Peter Solis Nery (born 1969) Prolific writer, poet, playwright, novelist, editor, "Hari sang Binalaybay", and champion of the Hiligaynon language. Born in Dumangas.

- Antonio Ledesma Jayme (1854–1937) Lawyer, revolutionary, provincial governor and assemblyman. Born in Jaro, lived in Bacolod.

- Graciano López Jaena (1856–1896) Journalist, orator, and revolutionary from Iloilo, well known for his written works, La Solidaridad and Fray Botod. Born in Jaro.

- Flavio Zaragoza y Cano (1892–1994) Lawyer, journalist and the "Prince of Visayan poets". Born in Janipaan, Cabatuan..

- Conrado Saquian Norada (1921– ) Lawyer, intelligence officer and governor of Iloilo from 1969 to 1986. Co-founder and editor of Yuhum magazine. Born in Miag-ao.

- Ramon Muzones (March 20, 1913 - August 17, 1992) Prolific writer and lawyer, recipient of the National Artist of the Philippines for Literature award. Born in Miag-ao.

- Magdalena Jalandoni (1891–1978) Prolific writer, novelist and feminist. Born in Jaro.

- Angel Magahum Sr. (1876–1931) Writer, editor and composer. Composed the classic Iloilo ang Banwa Ko, the unofficial song of Iloilo. Born in Molo.

- Valente Cristobal (1875–1945) Noted Hiligaynon playwright. Born in Polo (now Valenzuela City), Bulacan.

- Elizabeth Batiduan Navarro Hiligaynon drama writer for radio programs of Bombo Radyo Philippines.

- Genevieve L. Asenjo is a Filipino poet, novelist, translator and literary scholar in Kinaray-a, Hiligaynon and Filipino. Her first novel, Lumbay ng Dila, (C&E/DLSU, 2010) received a citation for the Juan C. Laya Prize for Excellence in Fiction in a Philippine Language in the National Book Award.

See also

- Cebuano language

- Hiligaynon people

- Languages of the Philippines

- Kinaray-a language

- Capiznon language

References

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A - Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables)" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A - Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables)" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- Lewis, M. Paul (2009). "Hiligaynon". www.ethnologue.com/. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- Ulrich Ammon; Norbert Dittmar; Klaus J. Mattheier (2006). Sociolinguistics: an international handbook of the science of language and society. Vol. 3. Walter de Gruyter. p. 2018. ISBN 978-3-11-018418-1.

- "Islas de los Pintados: The Visayan Islands". Ateneo de Manila University. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- Philippine Census, 2000. Table 11. Household Population by Ethnicity, Sex and Region: 2000

- "My Working Language Pairs". www.bj-informatique.com/. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, pp. 122-123.

- Cf. BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the Catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", pp. 120-121.

- Cf. Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo, June 1582) in BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", pp. 128 and 130.

- "Capiznon". ethnologue.com. Archived from the original on 2013-02-03.

- "Kinaray-a". ethnologue.com. Archived from the original on 2013-02-03.

- Wolfenden, Elmer (1971). Hiligaynon Reference Grammar. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 61–67. ISBN 0-87022-867-6.

- Motus, Cecile (1971). Hiligaynon Lessons. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 112–4. ISBN 0-87022-546-4.

- Wolfenden, Elmer (1971). Hiligaynon Reference Grammar. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 136–7. ISBN 0-87022-867-6.

- Spitz, Walter L. (February 1997), Lost Causes: Morphological Causative Constructions in Two Philippine Languages (Thesis), Digital Scholarship Archive, Rice University, p. 513, hdl:1911/19215, archived from the original on 2011-10-05

- Spitz, Walter L. (February 1997), Lost Causes: Morphological Causative Constructions in Two Philippine Languages (Thesis), Digital Scholarship Archive, Rice University, p. 514, hdl:1911/19215, archived from the original on 2011-10-05

- Spitz, Walter L. (February 1997), Lost Causes: Morphological Causative Constructions in Two Philippine Languages (Thesis), Digital Scholarship Archive, Rice University, pp. 514–515, hdl:1911/19215, archived from the original on 2011-10-05

Further reading

- Wolfenden, Elmer Paul (1972). A Description of Hiligaynon Phrase and Clause Constructions (Ph.D. thesis). University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/11716.

- Wolfenden, Elmer (1975). A Description of Hiligaynon Syntax. Norman, Oklahoma: Summer Institute of Linguistics. – published version of Wolfenden's 1972 dissertation

- Abuyen, Tomas Alvarez (2007). English–Tagalog–Ilongo Dictionary. Mandaluyong City: National Book Store. ISBN 978-971-08-6865-0.

External links

Dictionaries

- Hiligaynon Dictionary

- Hiligaynon to English Dictionary

- English to Hiligaynon Dictionary

- Bansa.org Hiligaynon Dictionary

- Kaufmann's 1934 Hiligaynon dictionary on-line

- Diccionario de la lengua Bisaya Hiligueina y Haraya de la Isla de Panay (by Alonso de Méntrida, published in 1841)

Learning Resources

- Some information about learning Ilonggo

- Hiligaynon Lessons (by Cecile L. Motus. 1971)

- Hiligaynon Reference Grammar (by Elmer Wolfenden 1971)

Writing System (Baybayin)

- Baybayin – The Ancient Script of the Philippines

- The evolution of the native Hiligaynon alphabet

- The evolution of the native Hiligaynon alphabet: Genocide

- The importance of the Hiligaynon 32-letter alphabet

Primary Texts

- Online E-book of Ang panilit sa pagcasal ñga si D.ª Angela Dionicia: sa mercader ñga contragusto in Hiligaynon, published in Mandurriao, Iloilo (perhaps, in the early 20th century)

Secondary Literature

- Language and Desire in Hiligaynon (by Corazón D. Villareal. 2006)

- Missionary Linguistics: selected papers from the First International Conference on Missionary Linguistics, Oslo, March 13–16th, 2003 (ed. by Otto Zwartjes and Even Hovdhaugen)