Impala

The impala or rooibok (Aepyceros melampus) is a medium-sized antelope found in eastern and southern Africa. The only extant member of the genus Aepyceros and tribe Aepycerotini, it was first described to European audiences by German zoologist Hinrich Lichtenstein in 1812. Two subspecies are recognised—the common impala, and the larger and darker black-faced impala. The impala reaches 70–92 cm (28–36 in) at the shoulder and weighs 40–76 kg (88–168 lb). It features a glossy, reddish brown coat. The male's slender, lyre-shaped horns are 45–92 cm (18–36 in) long.

| Impala | |

|---|---|

| |

| A territorial impala ram in northern Botswana | |

_female_and_young_(11421993164).jpg.webp) | |

| A ewe with calf at the Kruger National Park, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Tribe: | Aepycerotini |

| Genus: | Aepyceros |

| Species: | A. melampus |

| Binomial name | |

| Aepyceros melampus (Lichtenstein, 1812) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

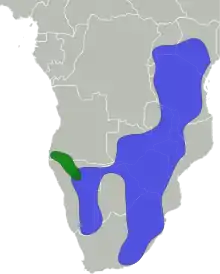

| Distribution:

Black-faced impala Common impala | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

Active mainly during the day, the impala may be gregarious or territorial depending upon the climate and geography. Three distinct social groups can be observed: the territorial males, bachelor herds and female herds. The impala is known for two characteristic leaps that constitute an anti-predator strategy. Browsers as well as grazers, impala feed on monocots, dicots, forbs, fruits and acacia pods (whenever available). An annual, three-week-long rut takes place toward the end of the wet season, typically in May. Rutting males fight over dominance, and the victorious male courts female in oestrus. Gestation lasts six to seven months, following which a single calf is born and immediately concealed in cover. Calves are suckled for four to six months; young males—forced out of the all-female groups—join bachelor herds, while females may stay back.

The impala is found in woodlands and sometimes on the interface (ecotone) between woodlands and savannahs; it inhabits places near water. While the black-faced impala is confined to southwestern Angola and Kaokoland in northwestern Namibia, the common impala is widespread across its range and has been reintroduced in Gabon and southern Africa. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies the impala as a species of least concern; the black-faced subspecies has been classified as a vulnerable species, with fewer than 1,000 individuals remaining in the wild as of 2008.

Etymology

The first attested English name, in 1802, was palla or pallah, from the Tswana phala 'red antelope';[3] the name impala, also spelled impalla or mpala, is first attested in 1875.[4] Its Afrikaans name, rooibok 'red buck', is also sometimes used in English.[5]

The scientific generic name Aepyceros (lit. ‘high-horned’) comes from Ancient Greek αἰπύς (aipus, 'high, steep') + κέρας (keras, 'horn');[6][7] the specific name melampus (lit. ‘black-foot’) from μελάς (melas, 'black') + πούς (pous, 'foot').[8]

Taxonomy and evolution

The impala is the sole member of the genus Aepyceros and belongs to the family Bovidae. It was first described by German zoologist Martin Hinrich Carl Lichtenstein in 1812.[2] In 1984, palaeontologist Elisabeth Vrba opined that the impala is a sister taxon to the alcelaphines, given its resemblance to the hartebeest.[9] A 1999 phylogenetic study by Alexandre Hassanin (of the National Centre for Scientific Research, Paris) and colleagues, based on mitochondrial and nuclear analyses, showed that the impala forms a clade with the suni (Neotragus moschatus). This clade is sister to another formed by the bay duiker (Cephalophus dorsalis) and the klipspringer (Oreotragus oreotragus).[10] An rRNA and β-spectrin nuclear sequence analysis in 2003 also supported an association between Aepyceros and Neotragus.[11] The following cladogram is based on the 1999 study:[10]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Up to six subspecies have been described, although only two are generally recognised on the basis of mitochondrial data.[12] Though morphologically similar,[13] the subspecies show a significant genetic distance between them, and no hybrids between them have been reported.[13][14]

- A. m. melampus Lichtenstein, 1812: Known as the common impala, it occurs across eastern and southern Africa. The range extends from central Kenya to South Africa and westward into southeastern Angola.

- A. m. petersi Bocage, 1879: Known as the black-faced impala, it is restricted to southwestern Africa, occurring in northwestern Namibia and southwestern Angola.

According to Vrba, the impala evolved from an alcelaphine ancestor. She noted that while this ancestor has diverged at least 18 times into various morphologically different forms, the impala has continued in its basic form for at least five million years.[9][15] Several fossil species have been discovered, including A. datoadeni from the Pliocene of Ethiopia.[16] The oldest fossil discovered suggests its ancient ancestors were slightly smaller than the modern form, but otherwise very similar in all aspects to the latter. This implies that the impala has efficiently adapted to its environment since prehistoric times. Its gregarious nature, variety in diet, positive population trend, defence against ticks and symbiotic relationship with the tick-feeding oxpeckers could have played a role in preventing major changes in morphology and behaviour.[9]

Description

The impala is a medium-sized, slender antelope similar to the kob or Grant's gazelle in build.[17] The head-and-body length is around 130 centimetres (51 in).[18] Males reach approximately 75–92 centimetres (30–36 in) at the shoulder, while females are 70–85 centimetres (28–33 in) tall. Males typically weigh 53–76 kilograms (117–168 lb) and females 40–53 kilograms (88–117 lb). Sexually dimorphic, females are hornless and smaller than males. Males grow slender, lyre-shaped horns 45–92 centimetres (18–36 in) long.[17] The horns, strongly ridged and divergent, are circular in section and hollow at the base. Their arch-like structure allows interlocking of horns, which helps a male throw off his opponent during fights; horns also protect the skull from damage.[13][17]

The glossy coat of the impala shows two-tone colouration – the reddish brown back and the tan flanks; these are in sharp contrast to the white underbelly. Facial features include white rings around the eyes and a light chin and snout. The ears, 17 centimetres (6.7 in) long, are tipped with black.[13][19] Black streaks run from the buttocks to the upper hindlegs. The bushy white tail, 30 centimetres (12 in) long, features a solid black stripe along the midline.[19] The impala's colouration bears a strong resemblance to the gerenuk, which has shorter horns and lacks the black thigh stripes of the impala.[13] The impala has scent glands covered by a black tuft of hair on the hindlegs. Sebaceous glands concentrated on the forehead and dispersed on the torso of dominant males[17][20] are most active during the mating season, while those of females are only partially developed and do not undergo seasonal changes.[21] There are four nipples.[17]

Of the subspecies, the black-faced impala is significantly larger and darker than the common impala; melanism is responsible for the black colouration.[22] Distinctive of the black-faced impala is a dark stripe, on either side of the nose, that runs upward to the eyes and thins as it reaches the forehead.[18][19] Other differences include the larger black tip on the ear, and a bushier and nearly 30% longer tail in the black-faced impala.[13]

The impala has a special dental arrangement on the front lower jaw similar to the toothcomb seen in strepsirrhine primates,[23] which is used during allogrooming to comb the fur on the head and the neck and remove ectoparasites.[13][24]

Ecology and behaviour

The impala is diurnal (active mainly during the day), though activity tends to cease during the hot midday hours; they feed and rest at night.[17] Three distinct social groups can be observed – the territorial males, bachelor herds and female herds.[25] The territorial males hold territories where they may form harems of females; territories are demarcated with urine and faeces and defended against juvenile or male intruders.[17] Bachelor herds tend to be small, with less than 30 members. Individuals maintain distances of 2.5–3 metres (8.2–9.8 ft) from one another; while young and old males may interact, middle-aged males generally avoid one another except to spar. Female herds vary in size from 6 to 100; herds occupy home ranges of 80–180 hectares (200–440 acres; 0.31–0.69 sq mi). The mother–calf bond is weak, and breaks soon after weaning; juveniles leave the herds of their mothers to join other herds. Female herds tend to be loose and have no obvious leadership.[17][26] Allogrooming is an important means of social interaction in bachelor and female herds; in fact, the impala appears to be the only ungulate to display self-grooming as well as allogrooming. In allogrooming, females typically groom related impalas, while males associate with unrelated ones. Each partner grooms the other six to twelve times.[27]

Social behaviour is influenced by the climate and geography; as such, the impala are territorial at certain times of the year and gregarious at other times, and the length of these periods can vary broadly among populations. For instance, populations in southern Africa display territorial behaviour only during the few months of the rut, whereas in eastern African populations, territoriality is relatively minimal despite a protracted mating season. Moreover, territorial males often tolerate bachelors, and may even alternate between bachelorhood and territoriality at different times of the year. A study of impala in the Serengeti National Park showed that in 94% of the males, territoriality was observed for less than four months.[17]

The impala is an important prey species for several carnivores, such as cheetahs, leopards, wild dogs and lions. The antelope displays two characteristic leaps – it can jump up to 3 metres (9.8 ft), over vegetation and even other impala, covering distances of up to 10 metres (33 ft); the other type of leap involves a series of jumps in which the animal lands on its forelegs, moves its hindlegs mid-air in a kicking fashion, lands on all fours (stotting) and then rebounds. It leaps in either manner in different directions, probably to confuse predators.[13][28] At times, the impala may also conceal itself in vegetation to escape the eye of the predator.[29] The most prominent vocalisation is the loud roar, delivered through one to three loud snorts with the mouth closed, followed by two to ten deep grunts with the mouth open and the chin and tail raised; a typical roar can be heard up to 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) away.[17] Scent gland secretions identify a territorial male.[30] Impalas are sedentary; adult and middle-aged males, in particular, can hold their territories for years.[17]

Parasites

_on_impala_(Aepyceros_melampus).jpg.webp)

Common ixodid ticks collected from impala include Amblyomma hebraeum, Boophilus decoloratus, Hyalomma marginatum, Ixodes cavipalpus, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus and R. evertsi.[31][32][33] In Zimbabwe, heavy infestation by ticks such as R. appendiculatus has proved to be a major cause behind the high mortality of ungulates, as they can lead to tick paralysis. Impala have special adaptations for grooming, such as their characteristic dental arrangement, to manage ticks before they engorge; however, the extensive grooming needed to keep the tick load under control involves the risk of dehydration during summer, lower vigilance against predators and gradual wearing out of the teeth. A study showed that impala adjust the time devoted to grooming and the number of grooming bouts according to the seasonal prevalence of ticks.[31]

Impala are symbiotically related to oxpeckers,[34] which feed on ticks from those parts of the antelope's body which the animal cannot access by itself (such as the ears, neck, eyelids, forehead and underbelly). The impala is the smallest ungulate with which oxpeckers are associated. In a study it was observed that oxpeckers selectively attended to impala despite the presence of other animals such as Coke's hartebeest, Grant's gazelle, Thomson's gazelle and topi. A possible explanation for this could be that because the impala inhabits woodlands (which can have a high density of ticks), the impala could have greater mass of ticks per unit area of the body surface.[35] Another study showed that the oxpeckers prefer the ears over other parts of the body, probably because these parts show maximum tick infestation.[36] The bird has also been observed to perch on the udders of a female and pilfer its milk.[37]

Lice recorded from impala include Damalinia aepycerus, D. elongata, Linognathus aepycerus and L. nevilli; in a study, ivermectin (a medication against parasites) was found to have an effect on Boophilus decoloratus and Linognathus species, though not on Damalinia species.[38] In a study of impala in South Africa, the number of worms in juveniles showed an increase with age, reaching a peak when impala turned a year old. This study recorded worms of genera such as Cooperia, Cooperoides, Fasciola, Gongylonema. Haemonchus, Impalaia, Longistrongylus and Trichostrongylus; some of these showed seasonal variations in density.[39]

Imapala show high frequency of defensive behaviours towards flying insects.[40] This is probably the reason for Vale 1977 and Clausen et al 1998 only finding trace levels of feeding by Glossina (tsetse fly) upon impala.[40]

Theileria of impala in Kenya are not cross infectious to cattle: Grootenhuis et al 1975 were not able to induce cattle infection and Fawcett et al 1987 did not find it naturally occurring.[41]

Diet

.jpg.webp)

Impala browse as well as graze; either may predominate, depending upon the availability of resources.[42] The diet comprises monocots, dicots, forbs, fruits and acacia pods (whenever available). Impala prefer places close to water sources, and resort to succulent vegetation if water is scarce.[17] An analysis showed that the diet of impala is composed of 45% monocots, 45% dicots and 10% fruits; the proportion of grasses in the diet increases significantly (to as high as 90%) after the first rains, but declines in the dry season.[43] Browsing predominates in the late wet and dry season, and diets are nutritionally poor in the mid-dry season, when impala feed mostly on woody dicots.[13][44] Another study showed that the dicot proportion in the diet is much higher in bachelors and females than in territorial males.[45]

Impala feed on soft and nutritious grasses such as Digitaria macroblephara; tough, tall grasses, such as Heteropogon contortus and Themeda triandra, are typically avoided.[46] Impala on the periphery of the herds are generally more vigilant against predators than those feeding in the centre; a foraging individual will try to defend the patch it is feeding on by lowering its head.[47] A study revealed that time spent in foraging reaches a maximum of 75.5% of the day in the late dry season, decreases through the rainy season, and is minimal in the early dry season (57.8%).[48]

Reproduction

Males are sexually mature by the time they are a year old, though successful mating generally occurs only after four years. Mature males start establishing territories and try to gain access to females. Females can conceive after they are a year and a half old; oestrus lasts for 24 to 48 hours, and occurs every 12–29 days in non-pregnant females.[29] The annual three-week-long rut (breeding season) begins toward the end of the wet season, typically in May. Gonadal growth and hormone production in males begin a few months before the breeding season, resulting in greater aggressiveness and territoriality.[17] The bulbourethral glands are heavier, testosterone levels are nearly twice as high in territorial males as in bachelors,[49] and the neck of a territorial male tends to be thicker than that of a bachelor during the rut. Mating tends to take place between full moons.[17]

Rutting males fight over dominance, often giving out noisy roars and chasing one another; they walk stiffly and display their neck and horns. Males desist from feeding and allogrooming during the rut, probably to devote more time to garnering females in oestrus;[50] the male checks the female's urine to ensure that she is in oestrus.[51][50] On coming across such a female, the excited male begins the courtship by pursuing her, keeping a distance of 3–5 metres (9.8–16.4 ft) from her. The male flicks his tongue and may nod vigorously; the female allows him to lick her vulva, and holds her tail to one side. The male tries mounting the female, holding his head high and clasping her sides with his forelegs. Mounting attempts may be repeated every few seconds to every minute or two. The male loses interest in the female after the first copulation, though she is still active and can mate with other males.[17][25]

Gestation lasts six to seven months. Births generally occur in the midday; the female will isolate herself from the herd when labour pain begins.[52] The perception that females can delay giving birth for an additional month if conditions are harsh may however not be realistic.[53] A single calf is born, and is immediately concealed in cover for the first few weeks of its birth. The fawn then joins a nursery group within its mother's herd. Calves are suckled for four to six months; young males, forced out of the group, join bachelor herds, while females may stay back.[17]

Distribution and habitat

The impala inhabits woodlands due to its preference for shade; it can also be found on the interface (ecotone) between woodlands and savannahs. Places near water sources are preferred. In southern Africa, populations tend to be associated with Colophospermum mopane and Acacia woodlands.[17][42] Habitat choices differ seasonally – Acacia senegal woodlands are preferred in the wet season, and A. drepanolobium savannahs in the dry season. Another factor that could influence habitat choice is vulnerability to predators; impala tend to keep away from areas with tall grasses as predators could be concealed there.[46] A study found that the reduction of woodland cover and creation of shrublands by the African bush elephants has favoured impala population by increasing the availability of more dry season browse. Earlier, the Baikiaea woodland, which has now declined due to elephants, provided minimum browsing for impala. The newly formed Capparis shrubland, on the other hand, could be a key browsing habitat.[54] Impala are generally not associated with montane habitats;[13] however, in KwaZulu-Natal, impala have been recorded at altitudes of up to 1,400 metres (4,600 ft) above sea level.[42]

The historical range of the impala – spanning across southern and eastern Africa – has remained intact to a great extent, although it has disappeared from a few places, such as Burundi. The range extends from central and southern Kenya and northeastern Uganda in the east to northern KwaZulu-Natal in the south, and westward up to Namibia and southern Angola. The black-faced impala is confined to southwestern Angola and Kaokoland in northwestern Namibia; the status of this subspecies has not been monitored since the 2000s. The common impala has a wider distribution, and has been introduced in protected areas in Gabon and across southern Africa.[1]

Threats and conservation

The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) classifies the impala as a species of least concern overall.[1] The black-faced impala, however, is classified as a vulnerable species; as of 2008, fewer than 1,000 were estimated in the wild.[55] Though there are no major threats to the survival of the common impala, poaching and natural calamities have significantly contributed to the decline of the black-faced impala. As of 2008, the population of the common impala has been estimated at around two million.[1] According to some studies, translocation of the black-faced impala can be highly beneficial in its conservation.[56][57]

Around a quarter of the common impala populations occur in protected areas, such as the Okavango Delta (Botswana); Masai Mara and Kajiado (Kenya); Kruger National Park (South Africa); the Ruaha and Serengeti National Parks and Selous Game Reserve (Tanzania); Luangwa Valley (Zambia); Hwange, Sebungwe and Zambezi Valley (Zimbabwe). The rare black-faced impala has been introduced into private farms in Namibia and the Etosha National Park. Population densities vary largely from place to place; from less than one impala per square kilometre in Mkomazi National Park (Tanzania) to as high as 135 per square kilometre near Lake Kariba (Zimbabwe).[1][58]

References

- IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2016). "Aepyceros melampus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T550A50180828. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T550A50180828.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Artiodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 673. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, March 2005, s.v. pallah

- Oxford English Dictionary Supp., 1933, s.v.

- Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, November 2010, s.v.

- "Aepyceros". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- Briggs, M.; Briggs, P. (2006). The Encyclopedia of World Wildlife. Somerset, UK: Parragon Publishers. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-4054-8292-9.

- Huffman, B. "Impala (Aepyceros melampus)". Ultimate Ungulate. Ultimate Ungulate. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- Vrba, E.S. (1984). "Evolutionary pattern and process in the sister-group Alcelaphini-Aepycerotini (Mammalia: Bovidae)". In Eldredge, N.; Stanley, S.M. (eds.). Living Fossils. New York, USA: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4613-8271-3. OCLC 10403493.

- Hassanin, A.; Douzery, E.J.P. (1999). "Evolutionary affinities of the enigmatic saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) in the context of the molecular phylogeny of Bovidae". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 266 (1422): 893–900. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0720. PMC 1689916. PMID 10380679.

- Kuznetsova, M.V.; Kholodova, M.V. (2003). "Revision of phylogenetic relationships in the Antilopinae subfamily on the basis of the mitochondrial rRNA and β-spectrin nuclear gene sequences". Doklady Biological Sciences. 391 (1–6): 333–6. doi:10.1023/A:1025102617714. ISSN 1608-3105. PMID 14556525. S2CID 30920084.

- Nersting, L.G.; Arctander, P. (2001). "Phylogeography and conservation of impala and greater kudu". Molecular Ecology. 10 (3): 711–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01205.x. PMID 11298982. S2CID 23102044.

- Kingdon, J.; Happold, D.; Butynski, T.; Happold, M.; Hoffmann, M.; Kalina, J. (2013). Mammals of Africa. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 479–84. ISBN 978-1-4081-8996-2. OCLC 854973585.

- Lorenzen, E.D.; Arctander, P.; Siegismund, H.R. (2006). "Regional genetic structuring and evolutionary history of the impala (Aepyceros melampus)". Journal of Heredity. 97 (2): 119–32. doi:10.1093/jhered/esj012. PMID 16407525.

- Arctander, P.; Kat, P.W.; Simonsen, B.T.; Siegismund, H.R. (1996). "Population genetics of Kenyan impalas – consequences for conservation". In Smith, T.B.; Wayne, R.K. (eds.). Molecular Genetic Approaches in Conservation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 399–412. ISBN 978-0-19-534466-0. OCLC 666957480.

- Geraads, D.; Bobe, R.; Reed, K. (2012). "Pliocene Bovidae (Mammalia) from the Hadar Formation of Hadar and Ledi-Geraru, Lower Awash, Ethiopia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (1): 180–97. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.632046. S2CID 86230742.

- Estes, R.D. (2004). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates (4th ed.). Berkeley, US: University of California Press. pp. 158–66. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0. OCLC 19554262.

- Liebenberg, L. (1990). A Field Guide to the Animal Tracks of Southern Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: D. Philip. pp. 275–6. ISBN 978-0-86486-132-0. OCLC 24702472.

- Stuart, C.; Stuart, T. (2001). Field Guide to Mammals of Southern Africa (3rd ed.). Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Publishers. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-86872-537-3. OCLC 46643659.

- Armstrong, M. (2007). Wildlife and Plants. Vol. 9 (3rd ed.). New York, US: Marshall Cavendish. pp. 538–9. ISBN 978-0-7614-7693-1. OCLC 229311414.

- Welsch, U.; van Dyk, G.; Moss, D.; Feuerhake, F. (1998). "Cutaneous glands of male and female impalas (Aepyceros melampus): seasonal activity changes and secretory mechanisms". Cell and Tissue Research. 292 (2): 377–94. doi:10.1007/s004410051068. PMID 9560480. S2CID 3127722.

- Hoven, W. (2015). "Private game reserves in southern Africa". In van der Duim, R.; Lamers, M.; van Wijk, J. (eds.). Institutional Arrangements for Conservation, Development and Tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. pp. 101–18. ISBN 978-94-017-9528-9. OCLC 895661132.

- McKenzie, A.A. (1990). "The ruminant dental grooming apparatus". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 99 (2): 117–28. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1990.tb00564.x.

- Mills, G.; Hes, L. (1997). The Complete Book of Southern African Mammals (1st ed.). Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Publishers. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-947430-55-9. OCLC 37480533.

- Schenkel, R. (1966). "On sociology and behaviour in impala (Aepyceros melampus) Lichtenstein". African Journal of Ecology. 4 (1): 99–114. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1966.tb00887.x.

- Murray, M.G. (1981). "Structure of association in impala, Aepyceros melampus". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 9 (1): 23–33. doi:10.1007/BF00299849. S2CID 24117010.

- Hart, B.L.; Hart, L.A. (1992). "Reciprocal allogrooming in impala, Aepyceros melampus". Animal Behaviour. 44 (6): 1073–1083. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80319-7. S2CID 53165208.

- "Impala: Aepyceros melampus". National Geographic. 11 April 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Vol. 2 (6th ed.). Baltimore, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1194–6. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8. OCLC 39045218.

- Kingdon, J. (1989). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa. Vol. 3. London, UK: Academic Press. pp. 462–74. ISBN 978-0-226-43725-5. OCLC 48864096.

- Mooring, M.S. (1995). "The effect of tick challenge on grooming rate by impala" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 50 (2): 377–92. doi:10.1006/anbe.1995.0253. S2CID 53185353. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2016.

- Gallivan, G.J.; Culverwell, J.; Girdwood, R.; Surgeoner, G.A. (1995). "Ixodid ticks of impala (Aepyceros melampus) in Swaziland: effect of age class, sex, body condition and management". South African Journal of Zoology. 30 (4): 178–86. doi:10.1080/02541858.1995.11448385.

- Horak, I.G. (1982). "Parasites of domestic and wild animals in South Africa. XV. The seasonal prevalence of ectoparasites on impala and cattle in the Northern Transvaal". The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 49 (2): 85–93. PMID 7177586.

- Mikula P, Hadrava J, Albrecht T, Tryjanowski P. (2018) Large-scale assessment of commensalistic–mutualistic associations between African birds and herbivorous mammals using internet photos. PeerJ 6:e4520 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4520

- Hart, B.L.; Hart, L.A.; Mooring, M.S. (1990). "Differential foraging of oxpeckers on impala in comparison with sympatric antelope species". African Journal of Ecology. 28 (3): 240–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1990.tb01157.x.

- Mooring, M.S.; Mundy, P.J. (1996). "Interactions between impala and oxpeckers at Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe". African Journal of Ecology. 34 (1): 54–65. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1996.tb00594.x.

- Hussain Kanchwala (2022). "How Did We Start Drinking Milk Of The Ruminants? Are We The Only Species To Drink Milk Of Other Species?". ScienceABC.

- Horak, I.G.; Boomker, J.; Kingsley, S.A.; De Vos, V. (1983). "The efficacy of ivermectin against helminth and arthropod parasites of impala". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 54 (4): 251–3. PMID 6689430.

- Horak, I.G. (1978). "Parasites of domestic and wild animals in South Africa. X. Helminths in impala". The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 45 (4): 221–8. PMID 572950.

- Auty, Harriet; Morrison, Liam J.; Torr, Stephen J.; Lord, Jennifer (2016). "Transmission Dynamics of Rhodesian Sleeping Sickness at the Interface of Wildlife and Livestock Areas" (PDF). Trends in Parasitology. Cell Press. 32 (8): 608–621. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2016.05.003. ISSN 1471-4922. PMID 27262917.

- Grootenhuis, J.G.; Olubayo, R.O. (1993). "Disease research in the wildlife‐livestock interface in Kenya". Veterinary Quarterly. Royal Netherlands Veterinary Association+Flemish Veterinary Association (T&F). 15 (2): 55–59. doi:10.1080/01652176.1993.9694372. ISSN 0165-2176. PMID 8372423.

- Skinner, J.D.; Chimimba, C.T. (2005). The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 703–8. ISBN 978-0-521-84418-5. OCLC 62703884.

- Meissner, H.H.; Pieterse, E.; Potgieter, J.H.J. (1996). "Seasonal food selection and intake by male impala Aepyceros melampus in two habitats". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 26 (2): 56–63. ISSN 0379-4369.

- Dunham, K. M. (2009). "The diet of impala (Aepyceros melampus) in the Sengwa Wildlife Research Area, Rhodesia". Journal of Zoology. 192 (1): 41–57. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1980.tb04218.x.

- van Rooyen, A.F.; Skinner, J.D. (1989). "Dietary differences between the sexes in impala". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa. 47 (2): 181–5. doi:10.1080/00359198909520161.

- Jarman, P.J.; Sinclair, A.R.E. (1984). "Feeding strategy and the pattern of resource partitioning in ungulates". In Sinclair, A.R.E.; Norton-Griffths, M. (eds.). Serengeti, Dynamics of an Ecosystem. Chicago, US: University of Chicago Press. pp. 130–63. ISBN 978-0-226-76029-2. OCLC 29118101.

- Blanchard, P.; Sabatier, R.; Fritz, H. (2008). "Within-group spatial position and vigilance: a role also for competition? The case of impalas (Aepyceros melampus) with a controlled food supply". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 62 (12): 1863–8. doi:10.1007/s00265-008-0615-3. S2CID 11796268.

- Wronski, T. (September 2002). "Feeding ecology and foraging behaviour of impala Aepyceros melampus in Lake Mburo National Park, Uganda". African Journal of Ecology. 40 (3): 205–11. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2028.2002.00348.x.

- Bramley, P.S.; Neaves, W.B. (1972). "The relationship between social status and reproductive activity in male impala, Aepyceros melampus" (PDF). Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 31 (1): 77–81. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0310077. PMID 5078117.

- Mooring, M. S.; Hart, B. L. (1995). "Differential grooming rate and tick load of territorial male and female impala". Behavioral Ecology. 6 (1): 94–101. doi:10.1093/beheco/6.1.94.

- Hart, Lynette A., and Benjamin L. Hart. "Species-specific patterns of urine investigation and flehmen in Grant's gazelle (Gazella granti), Thomson's gazelle (G. thomsoni), impala (Aepyceros melampus), and eland (Taurotragus oryx)." Journal of Comparative Psychology 101.4 (1987): 299.

- Jarman, M.V. (1979). Impala Social Behaviour: Territory, Hierarchy, Mating, and the Use of Space. Berlin, Germany: Parey. pp. 1–92. ISBN 978-3-489-60936-0. OCLC 5638565.

- D'Araujo, Shaun (20 November 2016). "Can Impala Really Delay Their Births?". Londolozi Blog.

- Rutina, L.P.; Moe, S.R.; Swenson, J.E. (2005). "Elephant Loxodonta africana driven woodland conversion to shrubland improves dry-season browse availability for impalas Aepyceros melampus". Wildlife Biology. 11 (3): 207–13. doi:10.2981/0909-6396(2005)11[207:ELADWC]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 84372708.

- IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2017). "Aepyceros melampus ssp. petersi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T549A50180804. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T549A50180804.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Green, W.C.H.; Rothstein, A. (2008). "Translocation, hybridisation, and the endangered black-faced impala". Conservation Biology. 12 (2): 475–80. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.1998.96424.x. S2CID 85717262.

- Matson, T.; Goldizen, A.W.; Jarman, P.J. (2004). "Factors affecting the success of translocations of the black-faced impala in Namibia". Biological Conservation. 116 (3): 359–65. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00229-5.

- East, R. (1999). African Antelope Database 1998. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN Species Survival Commission. pp. 238–41. ISBN 978-2-8317-0477-7. OCLC 44634423.