James Earl Ray

James Earl Ray (March 10, 1928 – April 23, 1998) was an American man convicted for assassinating Martin Luther King Jr. at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. After this Ray was on the run and was captured in the UK. Ray was convicted in 1969 after entering a guilty plea—thus forgoing a jury trial and the possibility of a death sentence—and was sentenced to 99 years of imprisonment.

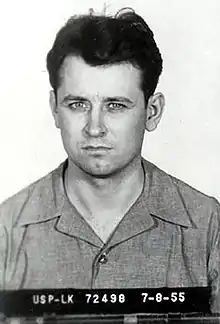

James Earl Ray | |

|---|---|

Mug shot of Ray taken on July 8, 1955 | |

| Born | March 10, 1928 Alton, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | April 23, 1998 (aged 70) Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Parent(s) | James Gerald Ray Lucille Ray |

| Conviction(s) | Murder, prison escape, armed robbery, burglary |

| Criminal penalty | 99 years in prison (one year was added after his re-capture for a total of 100 years) |

| Escaped | June 10, 1977 – June 13, 1977 |

| Details | |

| Victims | Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Date | April 4, 1968 |

Early life and education

Ray was born on March 10, 1928, in Alton, Illinois, the son of Lucille Ray (née Maher) and George Ellis Ray. He had Irish, Scottish and Welsh ancestry and had a Catholic upbringing.[1]

In February 1935, Ray's father, known by the nickname Speedy, passed a bad check in Alton, Illinois, and then moved to Ewing, Missouri, where the family changed their name to Raynes to avoid law enforcement.[2] Ray was the oldest of nine children,[3] including John Larry Ray,[4] Franklin Ray, Jerry William Ray,[5] Melba Ray, Carol Ray Pepper, Suzan Ray, and Marjorie Ray. His sister Marjorie died in a fire as a young child in 1933.[6] Ray left school at the age of 12. He later joined the U.S. Army at the close of World War II and served in Germany. Ray struggled to adapt to military life and was eventually discharged for ineptitude and lack of adaptability in 1948.[7]

Initial convictions and first escape from prison

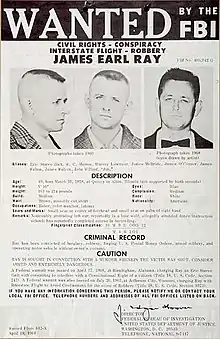

Ray committed a variety of crimes prior to the murder of King. Ray's first conviction for criminal activity, a burglary in California, came in 1949. In 1952, he served two years for the armed robbery of a taxi driver in Illinois. In 1955, he was convicted of mail fraud after stealing money orders in Hannibal, Missouri, then forging them to take a trip to Florida. He was imprisoned for four years in Leavenworth. In 1959, he was caught stealing $120 in an armed robbery of a Kroger store in St. Louis.[8] He was sentenced to twenty years in prison for repeated offenses. He escaped from the Missouri State Penitentiary in 1967 by hiding in a truck transporting bread from the prison bakery.[9]

Activity in 1967

Following his escape, Ray stayed on the move throughout the United States and Canada, going first to St. Louis and then onward to Chicago, Toronto, Montreal, and Birmingham, Alabama, where he stayed long enough to buy a 1966 Ford Mustang and get an Alabama driver license. He then drove to Mexico, stopping in Acapulco before settling in Puerto Vallarta on October 19, 1967.[10]

While in Mexico, Ray, using the alias Eric Starvo Galt, attempted to establish himself as a pornographic film director. Using mail-ordered equipment, he filmed and photographed local prostitutes. Frustrated with his results and jilted by the prostitute with whom he had formed a relationship, Ray left Mexico on or around November 16, 1967, [11] arriving in Los Angeles three days later. While there, Ray attended a local bartending school and took dance lessons.[12] His chief interest, however, was the George Wallace presidential campaign. Ray was a racist and was quickly drawn to Wallace's segregationist platform. He spent much of his time in Los Angeles volunteering at the Wallace campaign headquarters in North Hollywood.[13]

He considered emigrating to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), where a predominantly white minority regime had unilaterally assumed independence from the United Kingdom in 1965.[14] The notion of living in Rhodesia continued to appeal to Ray for several years afterwards, and it was his intended destination after King's assassination. The Rhodesian government expressed its disapproval.[15]

Activity in early 1968

On March 5, 1968, Ray underwent a rhinoplasty, performed by physician Russell Hadley.[16] On March 18, 1968, Ray left Los Angeles and began a cross-country drive to Atlanta, Georgia.[17]

Arriving in Atlanta on March 24, 1968, Ray checked into a rooming house.[18] He bought a map of the city. FBI agents later found this map when they searched the room in which he was staying. On the map, the locations of the church and residence of Martin Luther King Jr. were circled.[19]

Ray was soon on the road again and drove his Mustang to Birmingham, Alabama. There, on March 30, 1968, he bought a Remington Model 760 Gamemaster .30-06-caliber rifle and a box of 20 cartridges from the Aeromarine Supply Company. He also bought a Redfield 2x-7x scope, which he had mounted to the rifle.[20] He told the store owners that he was going on a hunting trip with his brother. Ray had continued using the Galt alias after his stint in Mexico, but when he made this purchase, he gave his name as Harvey Lowmeyer.[21]

After purchasing the rifle and accessories, Ray drove back to Atlanta. An avid newspaper reader, Ray passed his time reading The Atlanta Constitution. The paper reported King's planned return trip to Memphis, Tennessee, which was scheduled for April 1, 1968. On April 2, 1968, Ray packed a bag and drove to Memphis.[22]

Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

On April 4, 1968, Ray killed civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. with a single shot fired from his Remington rifle, while King was standing on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Shortly after the shot was fired, witnesses saw Ray fleeing from a rooming house across the street from the motel where he had been renting a room. A package was abandoned close to the site that included a rifle and binoculars, both found with Ray's fingerprints.[23][24][25]

Apprehension and plea

Ray fled to Atlanta in his white Ford Mustang, driving eleven hours.[26][27] He picked up his belongings and fled north to Canada, arriving in Toronto three days later, where he hid for over a month and acquired a Canadian passport under the false name of Ramon George Sneyd. He left Toronto in late May on a flight to England.[28] He stayed briefly in Lisbon, Portugal, and returned to London.[29] Ray was then arrested at London Heathrow Airport attempting to leave the United Kingdom for Brussels. He was trying to depart the United Kingdom for Angola, Rhodesia, or apartheid South Africa[30] using the falsified Canadian passport.[31] At check-in, the ticket agent noticed the name on his passport, Sneyd, was on a Royal Canadian Mounted Police watchlist.[32][33]

Airport officials noticed that Ray carried another passport under a second name. The UK quickly extradited Ray to Tennessee, where he was charged with King's murder. He confessed to the crime on March 10, 1969, his 41st birthday,[34] and after pleading guilty he was sentenced to 99 years in prison.[35]

Recanting of confession

Three days later, Ray recanted his confession. He had entered a guilty plea on the advice of his attorney, Percy Foreman, in an effort to avoid the sentence of death by electrocution, which would have been a possible outcome of a jury trial. Unbeknownst to Ray, however, under the de facto moratorium in place since 1967 and following Furman v. Georgia, a death sentence would have been commuted as unconstitutional.

Ray dismissed Foreman as his attorney and thereafter derisively called him "Percy Fourflusher." Ray began claiming that a man he had met in Montreal back in 1967, who used the alias "Raul," had been involved in the assassination. And he asserted that he did not "personally shoot Dr. King," but may have been "partially responsible without knowing it," hinting at a conspiracy. Ray told this version of the assassination and his own flight during the following two months to journalist William Bradford Huie.

Huie investigated this story and discovered that Ray lied about some details. Ray told Huie that he purposefully left the rifle with his fingerprints on it in plain sight at the crime scene because he wanted to become a famous criminal. He was convinced that he would escape capture because of his intelligence and cunning, and he also believed that Governor of Alabama George Wallace would soon be elected to the presidency, so that Ray would only be confined in prison for a short time, pending a presidential pardon by Wallace.[36] However, Ray spent the remainder of his life unsuccessfully attempting to withdraw his guilty plea and secure a jury trial.

Escape from prison

On June 10, 1977, Ray and six other convicts escaped from Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary in Petros, Tennessee. They were recaptured on June 13.[37] A year was added to Ray's previous sentence, increasing it to 100 years.

Conspiracy allegations

House Select Committee on Assassinations

| External video | |

|---|---|

Ray hired Jack Kershaw as his new attorney, and Kershaw publicly argued and promoted Ray's claim that he was not responsible for the assassination of King. His claim was that the assassination was the result of a conspiracy of the otherwise unidentified man named "Raul” who was a blond Cuban. Kershaw and his client met with representatives of the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) and convinced the committee to conduct ballistics tests that they believed would prove Ray had not fired the fatal shot.[38] The tests ultimately proved inconclusive.

Kershaw claimed the prison escape was additional proof that Ray had been involved in a conspiracy that had provided him with the outside assistance he would have needed to break out of prison. Kershaw convinced Ray to submit to a polygraph test as part of an interview with Playboy. The magazine reported that the test results showed "Ray did, in fact, kill Martin Luther King Jr. and that he did so alone." Ray then fired Kershaw after discovering the attorney had been paid $11,000 by the magazine in exchange for the interview and instead hired attorney Mark Lane to provide him with legal representation.[38]

Mock trial and civil suit

In 1997, King's son, Dexter, met with Ray at the prison and asked him, "I just want to ask you, for the record, did you kill my father?" Ray replied, "No. No I didn't." Dexter told Ray that he, along with the rest of the King family, believed Ray, and the family also urged publicly that Ray be granted a new trial.[39][40][41] William Pepper, a friend of King during the last year of his life, represented Ray in a mock trial televised by HBO in an attempt to grant him the trial he never received. In the mock trial, the prosecutor was Hickman Ewing. The mock trial jury finally acquitted Ray.[42]

In 1998, and continuing into 1999, Pepper represented the King family in a wrongful death civil suit against Memphis restaurant owner Loyd Jowers, whose restaurant was near the Lorraine Motel. They sued Jowers for participation in a conspiracy to murder King. Rendering their verdict on December 8 of that year, the jury found that Jowers and others, including government agencies, had conspired to murder King, and he was therefore legally liable to pay compensation to the King family. The family accepted $100 in restitution to demonstrate they were not pursuing the case for financial gain, and they publicly stated that Ray, in their opinion, had nothing to do with the assassination.[43] [44]

Coretta Scott King said, "The jury was clearly convinced by the extensive evidence that was presented during the trial that, in addition to Mr. Jowers, the conspiracy of the Mafia, local, state and federal government agencies, were deeply involved in the assassination of my husband. The jury also affirmed overwhelming evidence that identified someone else, not James Earl Ray, as the shooter, and that Mr. Ray was set up to take the blame."[45][46][47][48]

Prompted by the King family's acceptance of some of the claims of conspiracy, United States Attorney General Janet Reno ordered a new investigation on August 26, 1998.[49] On June 9, 2000, the United States Department of Justice released a 150-page report rejecting allegations that there was a conspiracy to assassinate King, including the determination of the Memphis civil court jury.[49]

Death

Before his death, Ray was transferred to the Lois M. DeBerry Special Needs Facility in Nashville, a maximum-security prison with hospital facilities.[50]

Ray died on April 23, 1998, at the age of 70, at the Columbia Nashville Memorial Hospital from complications related to kidney disease and liver failure caused by hepatitis C.[51] His brother, Jerry, told CNN that his brother did not want to be buried or have his final resting place in the United States because of the way the government had framed him for murder. His body was cremated and his ashes were flown to Ireland, the home of his maternal family's ancestors.[52]

Ten years later, Ray's other brother, John Larry Ray, co-authored a book with Lyndon Barsten, titled Truth At Last: The Untold Story Behind James Earl Ray and the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.[39]

References

- Ray, James Earl (1993). Who killed Martin Luther King?: the true story by the alleged assassin – James Earl Ray. ISBN 978-1-882605-02-6. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- Gerald Posner, Killing The Dream 1998

- Van Gelder, Lawrence (April 24, 1998). "James Earl Ray, 70, Killer of Dr. King, Dies in Nashville". The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Stelzer, C. D. (November 28, 2007). "The assassin's brother: John Larry Ray marks time in Quincy, still trying to set the record straight". Illinois Times. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- "James Earl Ray's Brother Dies". A Memoir of Injustice: Facebook Page. Facebook. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- "James Earl Ray Biography". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- biography.com

- Melanson, Philip H. (1994). The Martin Luther King Assassination. ISBN 978-1561711314. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- Gribben, Mark. "James Earl Ray: The Man Who Killed Dr. Martin Luther King, chapter 3". truTV Crime Library. truTV. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved June 25, 2006.

- Sides 2010, p. 7.

- Sides 2010, p. 33.

- Sides 2010, pp. 47–48.

- Sides 2010, p. 60.

- Sides 2010, pp. 62–63.

- Horne, Gerald (2001). From the Barrel of a Gun: The United States and the War against Zimbabwe, 1965–1980 (2000 ed.). University of North Carolina Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0807849033.

- Sides 2010, pp. 87–88.

- Sides 2010, pp. 90–91.

- Sides 2010, p. 98.

- Sides 2010, p. 302.

- "Report of laboratory, FBI headquarters to Memphis, Apr. 17, 1968, FBI headquarters Murkin file 44-38861" (PDF). The Harold Weisberg Archive. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- Sides 2010, pp. 118–120.

- Sides 2010, pp. 128–129.

- "Martin Luther King, Jr. Assassination". History.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- University, © Stanford; Stanford; California 94305 (April 24, 2017). "Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr". The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Findings on MLK Assassination". National Archives. August 15, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Findings on MLK Assassination". August 15, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- Gelder, Lawrence Van (April 24, 1998). "James Earl Ray, 70, Killer of Dr. King, Dies in Nashville". The New York Times. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- "Why assassin James Earl Ray returned to Toronto". Thestar.com. June 6, 2010. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- "Seeking answers on King's killer". April 4, 2008.

- Clarke, James W. (2007). Defining Danger: American Assassins and the New Domestic Terrorists. Piscataway, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0341-2.

- Borrell 1968, p. 2.

- Borrell, Clive (June 28, 1968). "Ramon Sneyd denies that he killed Dr King". The Times. London, UK. p. 2. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- R. Eyerman (2011). The Cultural Sociology of Political Assassination: From MLK and RFK to Fortuyn and van Gogh. Springer. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-0-230-33787-9.

- Waters, David; Charlier, Tom (April 24, 1998). "Log Cabin Democrat: King assassin Ray dies after lifelong legal fight 4/24/98". Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- "1969: Martin Luther King's killer gets life". On This Day 1950–2005: March 10. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). March 10, 1969.

- Huie 1997.

- "Federal Bureau of Investigation – History of Knoxville Office". FBI. Archived from the original on May 24, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- Martin, Douglas (September 24, 2010). "Jack Kershaw Is Dead at 96; Challenged Conviction in King's Death". New York Times. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- John Ray (brother of James Earl) on Fox at YouTube

- Today in History March 27 at YouTube

- Sack, Kevin (March 28, 1997). "Dr. King's Son Says Family Believes Ray Is Innocent". New York Times. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- "Ray Acquitted In Mock Trial 25 Years After King Slaying". Orlando Sentinel. April 5, 1993.

- "Memphis Jury Sees Conspiracy in Martin Luther King's Killing". New York Times. December 9, 1999.

- Sack, Kevin (March 28, 1997). "Dr. King's Son Says Family Believes Ray Is Innocent". New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- "Complete Transcript of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Assassination Conspiracy Trial" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Pepper, William; Gilardin, Maria (January 16, 2018). "The Execution of Martin Luther King – William Pepper (ONE of TWO)". TUC Radio. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- Pepper, William; Gilardin, Maria (January 23, 2018). "The Execution of Martin Luther King, William Pepper (TWO of TWO)". TUC Radio. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- "Assassination Conspiracy Trial Page". The King Center. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

This is the original King Center web page about the Assassination Conspiracy Trial. Includes the King Family Press Conference on the Verdict transcript.

- Sniffin, Michael J. (June 10, 2000). "Justice Dept. finds no conspiracy in King assassination". The Hour. Vol. 129, no. 159. Norwalk, Connecticut. AP. p. A4. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Yellin, Emily (March 28, 1998). "Third Inquiry Affirms Others: Ray Alone Was King's Killer". The New York Times. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Gelder, Lawerence (April 24, 1998). "James Earl Ray, 70, Killer of Dr. King, Dies in Nashville". The New York Times. Retrieved November 5, 2015 – via nytimes.com.

- "Autopsy confirms Ray died of liver failure". CNN. Nashville. April 24, 1998. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

Sources

- Huie, William Bradford (1997). He Slew the Dreamer: My Search for the Truth About James Earl Ray and the Murder of Martin Luther King. Montgomery: Black Belt Press. ISBN 978-1-57966-005-5.

- Sides, Hampton (2010). Hellhound on His Trail: The Stalking of Martin Luther King Jr. and the International Hunt for His Assassin. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-52392-9.

Further reading

- Green, Jim. Blood and Dishonor on a Badge of Honor.

- Heathrow, John. Why Did He Do It?

- McMillan, George. The Making of an Assassin. ISBN 978-0-316-56241-6

- Melanson, Dr. Philip H. The Martin Luther King Assassination: New Revelations on the Conspiracy and Cover-Up, 1968–1991. ISBN 978-1-56171-037-9

- Pepper, William F. An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King. ISBN 978-1-84467-285-1

- Petras, Kathryn, and Ross Petras (2003). Unusually Stupid Americans: A Compendium of All-American Stupidity. New York: Villard. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8129-7082-1.

- Posner, Gerald. Killing the Dream: James Earl Ray and the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. ISBN 978-0-15-600651-4

- Ray, James Earl with Tupper Saussy. Tennessee Waltz: The Making of a Political Prisoner. ISBN 978-0-911805-07-9

- Ray, James Earl (1992). Who Killed Martin Luther King?: The True Story by the Alleged Assassin. Washington: National Press Books. ISBN 0-915765-93-4.