Kublai Khan

Kublai[note 4] (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor[note 1] of the Mongol Empire from 1260 to 1294, although after the division of the empire this was a nominal position. He proclaimed the empire's dynastic name "Great Yuan"[note 5] in 1271, and ruled Yuan China until his death in 1294.

| Emperor Shizu of Yuan 元世祖 Setsen Khan 薛禪汗 ᠰᠡᠴᠡᠨ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠠᠨ | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th Khagan-Emperor of the Mongol Empire (nominal, due to the empire's division) Emperor of China (1st Emperor of the Yuan dynasty) | |||||||||||||||||||||

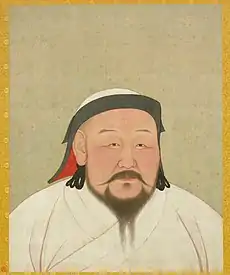

Portrait by artist Araniko, sling drawn shortly after Kublai's death in 1294. His white robes reflect his desired symbolic role as a religious Mongol shaman. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Khagan-Emperor of the Mongol Empire[note 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 21 August 1264 – 18 February 1294[note 2] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Coronation | 5 May 1260 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ariq Böke | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Temür Khan (Yuan dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Yuan dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 18 December 1271 – 18 February 1294[note 3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Temür Khan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 23 September 1215 Outer Mongolia | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 18 February 1294 (aged 78) Khanbaliq, Yuan China | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Burkhan Khaldun (now Khentii Province, Mongolia) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| House | Borjigin | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Yuan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Tolui | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Sorghaghtani Beki | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||||||

Kublai was the fourth son of Tolui (his second son with Sorghaghtani Beki) and a grandson of Genghis Khan. He was almost 12 when Genghis Khan died in 1227. He had succeeded his older brother Möngke as Khagan in 1260, but had to defeat his younger brother Ariq Böke in the Toluid Civil War lasting until 1264. This episode marked the beginning of the fragmentation of the empire.[5] Kublai's real power was limited to the Yuan Empire, even though as Khagan he still had influence in the Ilkhanate and, to a significantly lesser degree, in the Golden Horde.[6][7][8] If one considers the Mongol Empire at that time as a whole, his realm reached from the Pacific Ocean to the Black Sea, from Siberia to what is now Afghanistan.[9]

In 1271, Kublai established the Yuan dynasty and formally claimed orthodox succession from prior Chinese dynasties.[10] The Yuan dynasty came to rule over most of present-day China, Mongolia, Korea, southern Siberia, and other adjacent areas. He also amassed influence in the Middle East and Europe as khagan. By 1279, the Yuan conquest of the Song dynasty was completed and Kublai became the first non-Han emperor to rule all of China proper.

The imperial portrait of Kublai was part of an album of the portraits of Yuan emperors and empresses, now in the collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei. White, the color of the imperial costume of Kublai, was the imperial color of the Yuan dynasty based on the Chinese philosophical concept of the Five Elements.[11]

Early years

Kublai Khan was the fourth son of Tolui, and his second son with Sorghaghtani Beki. As his grandfather Genghis Khan advised, Sorghaghtani chose a Buddhist Tangut woman as her son's nurse, whom Kublai later honored highly. On his way home after the Mongol conquest of Khwarezmia, Genghis Khan performed a ceremony on his grandsons Möngke and Kublai after their first hunt in 1224 near the Ili River.[12] Kublai was nine years old and with his eldest brother killed a rabbit and an antelope. After his grandfather smeared fat from killed animals onto Kublai's middle finger in accordance with a Mongol tradition, he said "The words of this boy Kublai are full of wisdom, heed them well – heed them all of you." The elderly Genghis Khan would die three years after this event in 1227, when Kublai was 12. Kublai's father Tolui would serve as regent for two years until Genghis' successor, Kublai's third uncle Ogedei, was enthroned as Khagan in 1229.

After the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty, in 1236, Ogedei gave Hebei (attached with 80,000 households) to the family of Tolui, who died in 1232. Kublai received an estate of his own, which included 10,000 households. Because he was inexperienced, Kublai allowed local officials free rein. Corruption amongst his officials and aggressive taxation caused large numbers of ethnic Han peasants to flee, which led to a decline in tax revenues. Kublai quickly came to his appanage in Hebei and ordered reforms. Sorghaghtani Beki sent new officials to help him and tax laws were revised. Thanks to those efforts, many of the people who fled returned.

The most prominent, and arguably most influential, component of Kublai Khan's early life was his study and a strong attraction to contemporary Han culture. Kublai invited Haiyun, the leading Buddhist monk in northern China, to his ordo in Mongolia. When he met Haiyun in Karakorum in 1242, Kublai asked him about the philosophy of Buddhism. Haiyun named Kublai's son, who was born in 1243, Zhenjin (Chinese: True Gold).[13] Haiyun also introduced Kublai to the formerly Daoist (Taoist), and at the time Buddhist monk, Liu Bingzhong. Liu was a painter, calligrapher, poet, and mathematician, and he became Kublai's advisor when Haiyun returned to his temple in modern Beijing.[14] Kublai soon added the Shanxi scholar Zhao Bi to his entourage. Kublai employed people of other nationalities as well, for he was keen to balance local and imperial interests, Mongol and Turkic.

Victory in northern China

In 1251, Kublai's eldest brother Möngke became Khan of the Mongol Empire, and Khwarizmian Mahmud Yalavach and Kublai were sent to China. Kublai received the viceroyalty over northern China and moved his ordo to central Inner Mongolia. During his years as viceroy, Kublai managed his territory well, boosted the agricultural output of Henan, and increased social welfare spendings after receiving Xi'an. These acts received great acclaim from ethnic Han warlords and were essential to the founding of the Yuan dynasty. In 1252, Kublai criticized Mahmud Yalavach, who was never highly valued by his ethnic Han associates, over his cavalier execution of suspects during a judicial review, and Zhao Bi attacked him for his presumptuous attitude toward the throne. Möngke dismissed Mahmud Yalavach, which met with resistance from Han Confucian-trained officials.[15]

In 1253, Kublai was ordered to attack Yunnan and he tried to ask the Dali Kingdom to submit. The ruling Gao family resisted and killed Mongol envoys. The Mongols divided their forces into three. One wing rode eastward into the Sichuan basin. The second column under Subutai's son Uryankhadai took a difficult route into the mountains of western Sichuan.[16] Kublai went south over the grasslands and met up with the first column. While Uryankhadai travelled along the lakeside from the north, Kublai took the capital city of Dali and spared the residents despite the slaying of his ambassadors. The Dali emperor Duan Xingzhi (段興智) himself defected to the Mongols, who used his troops to conquer the rest of Yunnan. Duan Xingzhi, the last king of Dali, was appointed by Möngke Khan as the first tusi or local ruler; Duan accepted the stationing of a pacification commissioner there.[17] After Kublai's departure, unrest broke out among certain factions. In 1255 and 1256, Duan Xingzhi was presented at court, where he offered Möngke Khan maps of Yunnan and counsels about the vanquishing of the tribes who had not yet surrendered. Duan then led a considerable army to serve as guides and vanguards for the Mongol army. By the end of 1256, Uryankhadai had completely pacified Yunnan.[18]

Kublai was attracted by the abilities of Tibetan monks as healers. In 1253 he made Drogön Chögyal Phagpa of the Sakya school, a member of his entourage. Phagpa bestowed on Kublai and his wife, Chabi (Chabui), an empowerment (initiation ritual). Kublai appointed Lian Xixian of the Kingdom of Qocho (1231–1280) the head of his pacification commission in 1254. Some officials, who were jealous of Kublai's success, said that he was getting above himself and dreaming of having his own empire by competing with Möngke's capital Karakorum. Möngke Khan sent two tax inspectors, Alamdar (Ariq Böke's close friend and governor in North China) and Liu Taiping, to audit Kublai's officials in 1257. They found fault, listed 142 breaches of regulations, accused Han officials and executed some of them, and Kublai's new pacification commission was abolished.[19] Kublai sent a two-man embassy with his wives and then appealed in person to Möngke, who publicly forgave his younger brother and reconciled with him.

The Daoists had obtained their wealth and status by seizing Buddhist temples. Möngke repeatedly demanded that the Daoists cease their denigration of Buddhism and ordered Kublai to end the clerical strife between the Daoists and Buddhists in his territory.[20] Kublai called a conference of Daoist and Buddhist leaders in early 1258. At the conference, the Daoist claim was officially refuted, and Kublai forcibly converted 237 Daoist temples to Buddhism and destroyed all copies of the Daoist texts.[21][22][23][24] Kublai Khan and the Yuan dynasty clearly favored Buddhism, while his counterparts in the Chagatai Khanate, the Golden Horde, and the Ilkhanate later converted to Islam at various times in history – Berke of the Golden Horde being the only Muslim during Kublai's era (his successor did not convert to Islam).

In 1258, Möngke put Kublai in command of the Eastern Army and summoned him to assist with an attack on Sichuan. As he was suffering from gout, Kublai was allowed to stay home, but he moved to assist Möngke anyway. Before Kublai arrived in 1259, word reached him that Möngke had died. Kublai decided to keep the death of his brother secret and continued the attack on Wuhan, near the Yangtze. While Kublai's force besieged Wuchang, Uryankhadai joined him. The Song minister Jia Sidao secretly approached Kublai to propose terms. He offered an annual tribute of 200,000 taels of silver and 200,000 bolts of silk, in exchange for Mongol agreement to the Yangtze as the frontier between the states.[25] Kublai declined at first but later reached a peace agreement with Jia Sidao.

Enthronement and civil war

Kublai received a message from his wife that his younger brother Ariq Böke had been raising troops, so he returned north to the Mongolian Plateau.[26] Before he arrived, he learned that Ariq Böke had held a kurultai (Mongol great council) at the capital Karakorum, which had named him Great Khan with the support of most of Genghis Khan's descendants. Kublai and the fourth brother, the Il-Khan Hulagu, opposed this. Kublai's ethnic Han staff encouraged Kublai to ascend the throne, and almost all the senior princes in northern China and Manchuria supported his candidacy.[27] Upon returning to his own territories, Kublai summoned his own kurultai. Fewer members of the royal family supported Kublai's claims to the title, though the small number of attendees included representatives of all the Borjigin lines except that of Jochi. This kurultai proclaimed Kublai Great Khan, on April 15, 1260, despite Ariq Böke's apparently legal claim to become khan.

This led to warfare between Kublai and Ariq Böke, which resulted in the destruction of the Mongol capital at Karakorum. In Shaanxi and Sichuan, Möngke's army supported Ariq Böke. Kublai dispatched Lian Xixian to Shaanxi and Sichuan, where they executed Ariq Böke's civil administrator Liu Taiping and won over several wavering generals.[28] To secure the southern front, Kublai attempted a diplomatic resolution and sent envoys to Hangzhou, but Jia broke his promise and arrested them.[29] Kublai sent Abishqa as new khan to the Chagatai Khanate. Ariq Böke captured Abishqa, two other princes, and 100 men, and he had his own man, Alghu, crowned khan of Chagatai's territory. In the first armed clash between Ariq Böke and Kublai, Ariq Böke lost and his commander Alamdar was killed at the battle. In revenge, Ariq Böke had Abishqa executed. Kublai cut off supplies of food to Karakorum with the support of his cousin Kadan, son of Ögedei Khan. Karakorum quickly fell to Kublai's large army, but following Kublai's departure it was temporarily re-taken by Ariq Böke in 1261. Yizhou governor Li Tan revolted against Mongol rule in February 1262, and Kublai ordered his Chancellor Shi Tianze and Shi Shu to attack Li Tan. The two armies crushed Li Tan's revolt in just a few months and Li Tan was executed. These armies also executed Wang Wentong, Li Tan's father-in-law, who had been appointed the Chief Administrator of the Central Secretariat (Zhongshu Sheng) early in Kublai's reign and became one of Kublai's most trusted Han Chinese officials. The incident instilled in Kublai a distrust of ethnic Hans. After becoming emperor, Kublai banned granting the titles of and tithes to ethnic Han warlords.

Chagatayid Khan Alghu, who had been appointed by Ariq Böke, declared his allegiance to Kublai and defeated a punitive expedition sent by Ariq Böke in 1262. The Ilkhan Hulagu also sided with Kublai and criticized Ariq Böke. Ariq Böke surrendered to Kublai at Xanadu on August 21, 1264. The rulers of the western khanates acknowledged Kublai's victory and rule in Mongolia.[30] When Kublai summoned them to a new kurultai, Alghu Khan demanded recognition of his illegal position from Kublai in return. Despite tensions between them, both Hulagu and Berke, khan of the Golden Horde, at first accepted Kublai's invitation.[31][32] However, they soon declined to attend the kurultai. Kublai pardoned Ariq Böke, although he executed Ariq Böke's chief supporters.

Reign

Great Khan of the Mongols

The mysterious deaths of three Jochid princes in Hulagu's service, the Siege of Baghdad (1258), and unequal distribution of war spoils strained the Ilkhanate's relations with the Golden Horde. In 1262, Hulagu's complete purge of the Jochid troops and support for Kublai in his conflict with Ariq Böke brought open war with the Golden Horde. Kublai reinforced Hulagu with 30,000 young Mongols in order to stabilize the political crises in the western regions of the Mongol Empire.[33] When Hulagu died on February 8, 1264, Berke marched to cross near Tbilisi to conquer the Ilkhanate but died on the way. Within a few months of these deaths, Alghu Khan of the Chagatai Khanate also died. In the new official version of his family's history, Kublai refused to write Berke's name as the khan of the Golden Horde because of Berke's support for Ariq Böke and wars with Hulagu; however, Jochi's family was fully recognized as legitimate family members.[34]

Kublai Khan named Abaqa as the new Ilkhan (obedient khan) and nominated Batu's grandson Mentemu for the throne of Sarai, the capital of the Golden Horde.[35][36] The Kublaids in the east retained suzerainty over the Ilkhans until the end of their regime.[27][37] Kublai also sent his protege Ghiyas-ud-din Baraq to overthrow the court of the Oirat Orghana, the empress of the Chagatai Khanate, who put her young son Mubarak Shah on the throne in 1265, without Kublai's permission after her husband's death.

Prince Kaidu of the House of Ögedei declined to personally attend the court of Kublai. Kublai instigated Baraq to attack Kaidu. Baraq began to expand his realm northward; he seized power in 1266 and fought Kaidu and the Golden Horde. He also pushed out Great Khan's overseer from the Tarim Basin. When Kaidu and Mentemu together defeated Kublai, Baraq joined an alliance with the House of Ögedei and the Golden Horde against Kublai in the east and Abagha in the west. Meanwhile, Mentemu avoided any direct military expedition against Kublai's realm. The Golden Horde promised Kublai their assistance to defeat Kaidu whom Mentemu called the rebel.[38] This was apparently due to the conflict between Kaidu and Mentemu over the agreement they made at the Talas kurultai. The armies of Mongol Persia defeated Baraq's invading forces in 1269. When Baraq died the next year, Kaidu took control of the Chagatai Khanate and recovered his alliance with Mentemu.

Meanwhile, Kublai tried to stabilize his control over the Korean Peninsula by mobilizing another Mongol invasion after he enthroned Wonjong of Goryeo (r. 1260–1274) in 1259 on Ganghwado. Kublai also forced two rulers of the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate to call a truce with each other in 1270 despite the Golden Horde's interests in the Middle East and the Caucasus.[39]

In 1260, Kublai sent one of his advisors, Hao Ching, to the court of Emperor Lizong of Song to say that if Lizong submitted to Kublai and surrender his dynasty, he would be granted some autonomy.[40] Emperor Lizong refused to meet Kublai's demands and imprisoned Hao Ching and when Kublai sent a delegation to release Hao Ching, Emperor Lizong sent them back.[40]

Kublai called two Iraqi siege engineers from the Ilkhanate in order to destroy the fortresses of Song China. After the fall of Xiangyang in 1273, Kublai's commanders, Aju and Liu Zheng, proposed a final campaign against the Song dynasty, and Kublai made Bayan of the Baarin the supreme commander.[41] Kublai ordered Möngke Temür to revise the second census of the Golden Horde to provide resources and men for his conquest of China.[42] The census took place in all parts of the Golden Horde, including Smolensk and Vitebsk in 1274–75. The Khans also sent Nogai Khan to the Balkans to strengthen Mongol influence there.[43]

Kublai renamed the Mongol regime in China Dai Yuan in 1271, and sought to sinicize his image as Emperor of China in order to win control of millions of Han Chinese people. When he moved his headquarters to Khanbaliq, also called Dadu, at modern-day Beijing, there was an uprising in the old capital Karakorum that he barely contained. Kublai's actions were condemned by traditionalists and his critics still accused him of being too closely tied to Han Chinese culture. They sent a message to him: "The old customs of our Empire are not those of the Han Chinese laws ... What will happen to the old customs?"[44][45] Kaidu attracted the other elites of Mongol Khanates, declaring himself to be a legitimate heir to the throne instead of Kublai, who had turned away from the ways of Genghis Khan.[46][47] Defections from Kublai's dynasty swelled the Ögedeids' forces.

The Song imperial family surrendered to the Yuan in 1276, making the Mongols the first non-Han Chinese peoples to conquer all of China. Three years later, Yuan marines crushed the last of the Song loyalists. The Song Empress Dowager and her grandson, Emperor Gong of Song, were then settled in Khanbaliq where they were given tax-free property, and Kublai's wife Chabi took a personal interest in their well-being. However, Kublai later had Emperor Gong sent away to become a monk to Zhangye.

Kublai succeeded in building a powerful empire, created an academy, offices, trade ports and canals and sponsored science and the arts. The record of the Mongols lists 20,166 public schools created during Kublai's reign.[46] Having achieved real or nominal dominion over much of Eurasia, and having successfully conquered China, Kublai was in a position to look beyond China.[48] However, Kublai's costly invasions of Vietnam (1258), Sakhalin (1264), Burma (1277), Champa (1282), and Vietnam again (1285) secured only the vassal status of those countries. Mongol invasions of Japan (1274 and 1281), the third invasion of Vietnam (1287–88), and the invasion of Java (1293) failed.

At the same time, Kublai's nephew Ilkhan Abagha tried to form a grand alliance of the Mongols and the Western European powers to defeat the Mamluks in Syria and North Africa that constantly invaded the Mongol dominions. Abagha and Kublai focused mostly on foreign alliances, and opened trade routes. Khagan Kublai dined with a large court every day, and met with many ambassadors and foreign merchants.

Kublai's son Nomukhan and his generals occupied Almaliq from 1266 to 1276. In 1277, a group of Genghisid princes under Möngke's son Shiregi rebelled, kidnapped Kublai's two sons and his general Antong and handed them over to Kaidu and Möngke Temür. The latter was still allied with Kaidu who fashioned an alliance with him in 1269, although Möngke Temür had promised Kublai his military support to protect Kublai from the Ögedeids.[46] Kublai's armies suppressed the rebellion and strengthened the Yuan garrisons in Mongolia and the Ili River basin. However, Kaidu took control over Almaliq.

In 1279–80, Kublai decreed death for those who performed slaughtering of cattle according to the legal codes of Islam (dhabihah) or Judaism (kashrut), which offended Mongolian custom.[49] When Tekuder seized the throne of the Ilkhanate in 1282, attempting to make peace with the Mamluks, Abaqa's old Mongols under prince Arghun appealed to Kublai. After the assassination of Ahmad Fanakati and execution of his sons, Kublai confirmed Arghun's coronation and awarded his commander in chief Buqa the title of chancellor.

Kublai's niece, Kelmish, who married a Khongirad general of the Golden Horde, was powerful enough to have Kublai's sons Nomuqan and Kokhchu returned. Three leaders of the Jochids, Tode Mongke, Köchü, and Nogai, agreed to release two princes.[50] The court of the Golden Horde returned the princes as a peace overture to the Yuan dynasty in 1282 and induced Kaidu to release Kublai's general. Konchi, khan of the White Horde, established friendly relations with the Yuan and the Ilkhanate, and as a reward received luxury gifts and grain from Kublai.[51] Despite political disagreement between contending branches of the family over the office of Khagan, the economic and commercial system continued.[52][53][54][55]

Emperor of the Yuan dynasty

Kublai Khan considered China his main base, realizing within a decade of his enthronement as Great Khan that he needed to concentrate on governing there.[56] From the beginning of his reign, he adopted Chinese political and cultural models and worked to minimize the influences of regional lords, who had held immense power before and during the Song dynasty. Kublai heavily relied on his Chinese advisers until about 1276. He had many Han Chinese advisers, such as Liu Bingzhong and Xu Heng, and employed many Buddhist Uyghurs, some of whom were resident commissioners running Chinese districts.[57]

Kublai also appointed the Sakya lama Drogön Chögyal Phagpa ("the Phags pa Lama") his Imperial Preceptor, giving him power over all the empire's Buddhist monks. In 1270, after the Phags pa Lama created the 'Phags-pa script, he was promoted to imperial preceptor. Kublai established the Supreme Control Commission under the Phags pa Lama to administer affairs of Tibetan and Chinese monks. During Phagspa's absence in Tibet, the Tibetan monk Sangha rose to high office and had the office renamed the Commission for Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs.[58][59] In 1286, Sangha became the dynasty's chief fiscal officer. However, their corruption later embittered Kublai, and he later relied wholly on younger Mongol aristocrats. Antong of the Jalairs and Bayan of the Baarin served as grand councillors from 1265, and Oz-temur of the Arulad headed the censorate. Borokhula's descendant, Ochicher, headed a kheshig (Mongolian imperial guard) and the palace provision commission.

In the eighth year of Zhiyuan (1271), Kublai officially created the Yuan dynasty and proclaimed the capital as Dadu (Chinese: 大都; Wade–Giles: Ta-tu; lit. 'Grand Capital', known as Khanbaliq or Daidu to the Mongols, at modern-day Beijing) the following year. His summer capital was in Shangdu (Chinese: 上都; lit. 'Upper Capital', also called Xanadu, near what today is Dolon Nor). To unify China,[60] Kublai began a massive offensive against the remnants of the Southern Song in 1274 and finally destroyed the Song in 1279, unifying the country at last at the Battle of Yamen where the last Song Emperor Zhao Bing committed suicide by jumping into the sea and ending the Song dynasty.[61]

Most of the Yuan domains were administered as provinces, also translated as the "Branch Secretariat", each with a governor and vice-governor.[62] This included China proper, Manchuria, Mongolia, and a special Zhendong branch Secretariat that extended into the Korean Peninsula.[63][64] The Central Region (Chinese: 腹裏) was separate from the rest, consisting of much of present-day North China. It was considered the most important region of the dynasty and was directly governed by the Zhongshu Sheng at Dadu. Tibet was governed by another top-level administrative department called the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs.

Kublai promoted economic growth by rebuilding the Grand Canal, repairing public buildings, and extending highways. However, his domestic policy included some aspects of the old Mongol living traditions, and as his reign continued, these traditions would clash increasingly frequently with traditional Chinese economic and social culture. Kublai decreed that partner merchants of the Mongols should be subject to taxes in 1262 and set up the Office of Market Taxes to supervise them in 1268.[65] After the Mongol conquest of the Song, the Muslim, Uighur and Chinese merchants expanded their operations to the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.[65] In 1286, maritime trade was put under the Office of Market Taxes. The main source of revenue of the government was the monopoly of salt production.[66]

The Mongol administration had issued paper currencies from 1227 on.[67][68] In August 1260, Kublai created the first unified paper currency called Jiaochao; bills were circulated throughout the Yuan domain with no expiration date. To guard against devaluation, the currency was convertible with silver and gold, and the government accepted tax payments in paper currency. In 1273, Kublai issued a new series of state sponsored bills to finance his conquest of the Song, although eventually a lack of fiscal discipline and inflation turned this move into an economic disaster. It was required to pay only in the form of paper money. To ensure its use, Kublai's government confiscated gold and silver from private citizens and foreign merchants, but traders received government-issued notes in exchange. Kublai Khan is considered to be the first fiat money maker. The paper bills made collecting taxes and administering the empire much easier and reduced the cost of transporting coins.[69] In 1287, Kublai's minister Sangha created a new currency, Zhiyuan Chao, to deal with a budget shortfall.[70] It was non-convertible and denominated in copper cash. Later Gaykhatu of the Ilkhanate attempted to adopt the system in Iran and the Middle East, which was a complete failure, and shortly afterwards he was assassinated.

桑哥 Sangha was a Tibetan.[71] A rich merchant from the Madurai Sultanate, Abu Ali (in Chinese, 孛哈里 Bèihālǐ or 布哈爾 Bùhār), was associated closely with its royal family. After falling out with them, he moved to Yuan China and received a Korean woman as his wife and a job from the Mongol Emperor, the woman was formerly Sangha's wife and her father held the title of 채송년 Chaesongnyeon during the reign of Chungnyeol of Goryeo according to the Dongguk Tonggam, Goryeosa and Liu Mengyan's Zhōng'ānjí (中俺集).[72][73]

Kublai encouraged Asian arts and demonstrated religious tolerance. Despite his anti-Daoist edicts, Kublai respected the Daoist master and appointed Zhang Liushan as the patriarch of the Daoist Xuánjiào (玄教, "Mysterious Order").[74] Under Zhang's advice, Daoist temples were put under the Academy of Scholarly Worthies. Several Europeans visited the empire, notably Marco Polo in the 1270s, who may have seen the summer capital Shangdu.

During the Southern Song, the descendant of Confucius at Qufu, Duke Yansheng Kong Duanyou fled south with the Song Emperor to Quzhou, while the newly established Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in the north appointed Kong Duanyou's brother Kong Duancao who remained in Qufu as Duke Yansheng. From that time up until the Yuan dynasty, there were two Duke Yanshengs, once in the north in Qufu and the other in the south at Quzhou. An invitation to come back to Qufu was extended to the southern Duke Yansheng Kong Zhu by the Yuan dynasty Emperor Kublai Khan. The title was taken away from the southern branch after Kong Zhu rejected the invitation, so the northern branch of the family kept the title of Duke Yansheng.[75][76][77][78][79][80][81] The southern branch still remained in Quzhou where they lived to this day. Confucius's descendants in Quzhou alone number 30,000.[82]

Yuan Emperors like Kublai Khan forbade practices such as butchering according to Jewish (kashrut) or Muslim (dhabihah) legal codes and other restrictive decrees continued. Circumcision was also strictly forbidden.[83][84][85]

Scientific developments and relations with minorities

Thirty Muslims served as high officials in the court of Kublai Khan. Eight of the dynasty's twelve administrative districts had Muslim governors appointed by Kublai Khan.[86] Among the Muslim governors was Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, who became administrator of Yunnan. He was a well learned man in the Confucian and Daoist traditions and is believed to have propagated Islam in China. Other administrators were Nasr al-Din (Yunnan) and Mahmud Yalavach (mayor of the Yuan capitol).

Kublai Khan patronized Muslim scholars and scientists, and Muslim astronomers contributed to the construction of the observatory in Shaanxi.[87] Astronomers such as Jamal ad-Din introduced 7 new instruments and concepts that allowed the correction of the Chinese calendar.

Muslim cartographers made accurate maps of all the nations along the Silk Road and greatly influenced the knowledge of Yuan dynasty rulers and merchants.

Muslim physicians organized hospitals and had their own institutes of Medicine in Beijing and Shangdu. In Beijing was the renown Guang Hui Si "Department of extensive mercy", where Hui medicine and surgery were taught. Avicenna's works were also published in China during that period.[88]

Muslim mathematicians introduced Euclidean Geometry, Spherical trigonometry and Arabic numerals in China.[89]

Kublai brought siege engineers Ismail and Al al-Din to China, and together they invented the "Muslim trebuchet" (or Huihui Pao), which was utilized by Kublai Khan during the Battle of Xiangyang.[90]

Warfare and foreign relations

Although Kublai restricted the functions of the kheshig, he created a new imperial bodyguard, at first entirely ethnic Han in composition but later strengthened with Kipchak, Alan (Asud), and Russian units.[91][92][93] Once his own kheshig was organized in 1263, Kublai put three of the original kheshigs under the charge of the descendants of Genghis Khan's assistants, Borokhula, Boorchu, and Muqali. Kublai began the practice of having the four great aristocrats in his kheshig sign jarligs (decrees), a practice that spread to all other Mongol khanates.[94] Mongol and Han units were organized using the same decimal organization that Genghis Khan used. The Mongols eagerly adopted new artillery and technologies. Kublai and his generals adopted an elaborate, moderate style of military campaigns in southern China. Effective assimilation of the naval techniques of the Han people allowed the Yuan army to quickly conquer the Song.

Tibet and Xinjiang

In 1285 the Drikung Kagyu sect revolted, attacking Sakya monasteries. The Chagatayid khan, Duwa, helped the rebels, laying siege to Gaochang and defeating Kublai's garrisons in the Tarim Basin.[95] Kaidu destroyed an army at Beshbalik and occupied the city the following year. Many Uyghurs abandoned Kashgar for safer bases back in the eastern part of the Yuan dynasty. After Kublai's grandson Buqa-Temür crushed the resistance of the Drikung Kagyu, killing 10,000 Tibetans in 1291, Tibet was fully pacified.

Annexation of Goryeo

Kublai Khan invaded Goryeo on the Korean Peninsula and made it a tributary vassal state in 1260. After another Mongol intervention in 1273, Goryeo came under even tighter control of the Yuan.[96][97][98][99][100] Goryeo became a Mongol military base, and several myriarchy commands were established there. The court of the Goryeo supplied Korean troops and an ocean-going naval force for the Mongol campaigns.

Further naval expansion

Despite the opposition of some of his Confucian-trained advisers, Kublai decided to invade Japan, Burma, Vietnam, and Java, following the suggestions of some of his Mongol officials. He also attempted to subjugate peripheral lands such as Sakhalin, where its indigenous people eventually submitted to the Mongols by 1308, after Kublai's death. These costly invasions and conquests and the introduction of paper currency caused inflation. From 1273 to 1276, war against the Southern Song dynasty and Japan made the issue of paper currency expand from 110,000 ding to 1,420,000 ding.[102]

Invasions of Japan

Within Kublai's court his most trusted governors and advisers appointed by meritocracy with the essence of multiculturalism were Mongol, Semu, Korean, Hui and Han peoples.[86][103] Because the Wokou extended support to the crumbling Southern Song dynasty, Kublai Khan initiated invasions of Japan.

Kublai Khan twice attempted to invade Japan. It is believed that both attempts were partly thwarted by bad weather or a flaw in the design of ships that were based on river boats without keels, and his fleets were destroyed. The first attempt took place in 1274, with a fleet of 900 ships.[104]

The second invasion occurred in 1281 when Mongols sent two separate forces: 900 ships containing 40,000 Korean, Han, and Mongol troops were sent from Masan, while a force of 100,000 sailed from southern China in 3,500 ships, each close to 240 feet (73 m) long. The fleet was hastily assembled and ill-equipped to cope with maritime conditions. In November, they sailed into the treacherous waters that separate Korea and Japan by 180 kilometres (110 miles). The Mongols easily took over Tsushima Island about halfway across the strait and then Iki Island closer to Kyushu. The Korean fleet reached Hakata Bay on June 23, 1281, and landed its troops and animals, but the ships from China were nowhere to be seen. Mongol landing forces were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Akasaka and the Battle of Torikai-Gata. Takezaki Suenaga's samurai attacked the Mongol army and fought them, as reinforcements led by Shiraishi Michiyasu arrived and defeated the Mongols, who suffered around 3500 dead.[105]

The samurai warriors, following their custom, rode out against the Mongol forces for individual combat but the Mongols held their formation. The Mongols fought as a united force, not as individuals, and bombarded the samurai with exploding missiles and showered them with arrows. Eventually, the remaining Japanese withdrew from the coastal zone inland to a fortress. The Mongol forces did not chase the fleeing Japanese into an area about which they lacked reliable intelligence. In a number of individual skirmishes, known collectively as the Kōan Campaign (弘安の役) or the "Second Battle of Hakata Bay", the Mongol forces were driven back to their ships by the Samurai. The Japanese army was heavily outnumbered, but had fortified the coastal line with two-meter high walls, and was easily able to repulse the Mongolian forces that were launched against it.

Maritime archaeologist Kenzo Hayashida led the investigation that discovered the wreckage of the second invasion fleet off the western coast of Takashima District, Shiga. His team's findings strongly indicate that Kublai rushed to invade Japan and attempted to construct his enormous fleet in one year, a task that should have taken up to five years. This forced the Chinese to use any available ships, including river boats. Most importantly, the Chinese, under Kublai's control, built many ships quickly in order to contribute to the fleets in both of the invasions. Hayashida theorizes that, had Kublai used standard, well-constructed ocean-going ships with curved keels to prevent capsizing, his navy might have survived the journey to and from Japan and might have conquered it as intended. In October 2011, a wreck, possibly one of Kublai's invasion craft, was found off the coast of Nagasaki.[106] David Nicolle wrote in The Mongol Warlords, "Huge losses had also been suffered in terms of casualties and sheer expense, while the myth of Mongol invincibility had been shattered throughout eastern Asia." He also wrote that Kublai was determined to mount a third invasion, despite the horrendous cost to the economy and to his and Mongol prestige of the first two defeats, and only his death and the unanimous agreement of his advisers not to invade prevented a third attempt.[107]

Invasions of Vietnam

Kublai Khan invaded Đại Việt/Annam (now Vietnam) in a total of five separate incursions between 1257-92, with major campaigns in 1258, 1285, and 1287. These three campaigns are treated by a number of scholars as a success due to the establishment of tributary relations with Đại Việt despite the Mongols suffering major military defeats.[108][109][110] In contrast, Vietnamese historiography regards the war as a major victory against the foreign invaders whom they called "the Mongol yokes."[111][108]

The first invasion began in 1258 under the united Mongol Empire, as it looked for alternative paths to invade the Song dynasty. The Mongol general Uriyangkhadai was successful in capturing the Vietnamese capital Thang Long (modern-day Hanoi) before turning north in 1259 to invade the Song dynasty in modern-day Guangxi as part of a coordinated Mongol attack with armies attacking in Sichuan under Möngke Khan and other Mongol armies attacking in modern-day Shandong and Henan.[112] The first invasion also established tributary relations between the Vietnamese dynasty, formerly a Song dynasty tributary state, and the Yuan dynasty.[113]

Intending to demand greater tribute and direct Yuan oversight of local affairs in Đại Việt and Champa, the Yuan launched another invasion in 1285. The second invasion of Đại Việt failed to accomplish its goals, and the Yuan launched a third invasion in 1287 with the intent of replacing the uncooperative Đại Việt ruler Trần Nhân Tông with the defected Trần prince Trần Ích Tắc. By the end of the second and third invasions, which involved both initial successes and eventual major defeats for the Mongols, both Đại Việt and Champa decided to accept the nominal supremacy of the Yuan dynasty and became tributary states to avoid further conflict.[114][115]

Southeast Asia and South Seas

Three expeditions against Burma, in 1277, 1283, and 1287, brought the Mongol forces to the Irrawaddy Delta, whereupon they captured Bagan, the capital of the Pagan Kingdom and established their government.[116] Kublai had to be content with establishing a formal suzerainty, but Pagan finally became a tributary state, sending tributes to the Yuan court until the Yuan dynasty fell to the Ming dynasty in 1368.[117] Mongol interests in these areas were commercial and tributary relationships.

Kublai Khan maintained close relations with Siam, in particular with prince Mangrai of Chiangmai and king Ram Khamheng of Sukhothai.[118] In fact, Kublai encouraged them to attack the Khmers after the Thais were being pushed southwards from Nanchao.[118][119][120] This happened after king Jayavarman VIII of the Khmer Empire refused to pay tribute to the Mongols.[118][121][122] Jayavarman VIII was so insistent on not having to pay tribute to Kublai that he had Mongol envoys imprisoned.[118][122][120] These attacks from the Siamese eventually weakened the Khmer Empire. The Mongols then decided to venture south into Cambodia in 1283 by land from Champa.[123] They were able to conquer Cambodia by 1284.[124] Cambodia effectively became a vassal state by 1285 when Jayavarman VIII was finally forced to pay tribute to Kublai.[123][125][126]

During the last years of his reign, Kublai launched a naval punitive expedition of 20–30,000 men against Singhasari on Java (1293), but the invading Mongol forces were forced to withdraw by Majapahit after considerable losses of more than 3000 troops. Nevertheless, by 1294, the year that Kublai died, the Thai kingdoms of Sukhothai and Chiang Mai had become vassal states of the Yuan dynasty.[116]

Europe

Under Kublai, direct contact between East Asia and Europe was established, made possible by Mongol control of the central Asian trade routes and facilitated by the presence of efficient postal services. In the beginning of the 13th century, Europeans and Central Asians – merchants, travelers, and missionaries of different orders – made their way to China. The presence of Mongol power allowed large numbers of Yuan subjects, intent on warfare or trade, to travel to other parts of the Mongol Empire, all the way to Rus, Persia, and Mesopotamia.

Africa

In the 13th century, the Sultanate of Mogadishu, through its trade with prior Chinese regimes, had acquired enough of a reputation in Asia to attract the attention of Kublai Khan.[127] According to Marco Polo, Kublai sent an envoy to Mogadishu to spy out the Sultanate but the delegation was captured and imprisoned. Kublai Khan then sent another envoy to treat for the release of the earlier Mongol delegation sent to Africa.[128]

Capital city

After Kublai Khan was proclaimed Khagan at his residence in Shangdu on May 5, 1260, he began to organize the country. Zhang Wenqian, a central government official, was sent by Kublai in 1260 to Daming where unrest had been reported in the local population. A friend of Zhang's, Guo Shoujing, accompanied him on this mission. Guo was interested in engineering, was an expert astronomer and skilled instrument maker, and he understood that good astronomical observations depended on expertly made instruments. Guo began to construct astronomical instruments, including water clocks for accurate timing and armillary spheres that represented the celestial globe. Turkestani architect Ikhtiyar al-Din, also known as "Igder", designed the buildings of the city of the Khagan, Khanbaliq (Dadu).[129] Kublai also employed foreign artists to build his new capital; one of them, a Newar named Araniko, built the White Stupa that was the largest structure in Khanbaliq/Dadu.[130]

Zhang advised Kublai that Guo was a leading expert in hydraulic engineering. Kublai knew the importance of water management for irrigation, transport of grain, and flood control, and he asked Guo to look at these aspects in the area between Dadu (now Beijing) and the Yellow River. To provide Dadu with a new supply of water, Guo found the Baifu spring in Mount Shen and had a 30 km (19 mi) channel built to move water to Dadu. He proposed connecting the water supply across different river basins, built new canals with sluices to control the water level, and achieved great success with the improvements he made. This pleased Kublai and Guo was asked to undertake similar projects in other parts of the country. In 1264 he was asked to go to Gansu to repair the damage that had been caused to the irrigation systems by the years of war during the Mongol advance through the region. Guo travelled extensively along with his friend Zhang taking notes of the work needed to be done to unblock damaged parts of the system and to make improvements to its efficiency. He sent his report directly to Kublai Khan.

Nayan's rebellion

During the conquest of the Jin, Genghis Khan's younger brothers received large appanages in Manchuria.[131] Their descendants strongly supported Kublai's coronation in 1260, but the younger generation desired more independence. Kublai enforced Ögedei Khan's regulations that the Mongol noblemen could appoint overseers and the Great Khan's special officials, in their appanages, but otherwise respected appanage rights. Kublai's son Manggala established direct control over Chang'an and Shanxi in 1272. In 1274, Kublai appointed Lian Xixian to investigate abuses of power by Mongol appanage holders in Manchuria.[132] The region called Lia-tung was immediately brought under the Khagan's control, in 1284, eliminating autonomy of the Mongol nobles there.[133]

Threatened by the advance of Kublai's bureaucratization, Nayan, a fourth-generation descendant of one of Genghis Khan's brothers, either Temüge or Belgutei, instigated a revolt in 1287. (More than one prince named Nayan existed and their identity is confused.[134]) Nayan tried to join forces with Kublai's competitor Kaidu in Central Asia.[135] Manchuria's native Jurchens and Water Tatars, who had suffered a famine, supported Nayan. Virtually all the fraternal lines under Hadaan, a descendant of Hachiun, and Shihtur, a grandson of Qasar, joined Nayan's rebellion,[136] and because Nayan was a popular prince, Ebugen, a grandson of Genghis Khan's son Khulgen, and the family of Khuden, a younger brother of Güyük Khan, contributed troops for this rebellion.[137]

The rebellion was crippled by early detection and timid leadership. Kublai sent Bayan to keep Nayan and Kaidu apart by occupying Karakorum, while Kublai led another army against the rebels in Manchuria. Kublai's commander Oz Temür's Mongol force attacked Nayan's 60,000 inexperienced soldiers on June 14, while ethnic Han and Alan guards under Li Ting protected Kublai. The army of Chungnyeol of Goryeo assisted Kublai in battle. After a hard fight, Nayan's troops withdrew behind their carts, and Li Ting began bombardment and attacked Nayan's camp that night. Kublai's force pursued Nayan, who was eventually captured and executed without bloodshed, by being smothered under felt carpets, a traditional way of executing princes.[137] Meanwhile, the rebel prince Shikqtur invaded Liaoning but was defeated within a month. Kaidu withdrew westward to avoid a battle. However, Kaidu defeated a major Yuan army in the Khangai Mountains and briefly occupied Karakorum in 1289. Kaidu had ridden away before Kublai could mobilize a larger army.[41]

Widespread but uncoordinated uprisings of Nayan's supporters continued until 1289; these were ruthlessly repressed. The rebel princes' troops were taken from them and redistributed among the imperial family.[138] Kublai harshly punished the darughachi appointed by the rebels in Mongolia and Manchuria.[139] This rebellion forced Kublai to approve the creation of the Liaoyang Branch Secretariat on December 4, 1287, while rewarding loyal fraternal princes.

Later years

Kublai Khan dispatched his grandson Gammala to Burkhan Khaldun in 1291 to ensure his claim to Ikh Khorig, where Genghis was buried, a sacred place strongly protected by the Kublaids. Bayan was in control of Karakorum and was re-establishing control over surrounding areas in 1293, so Kublai's rival Kaidu did not attempt any large-scale military action for the next three years. From 1293 on, Kublai's army cleared Kaidu's forces from the Central Siberian Plateau.

After his wife Chabi died in 1281, Kublai began to withdraw from direct contact with his advisers, and he issued instructions through one of his other queens, Nambui. Only two of Kublai's daughters are known by name; he may have had others. Unlike the formidable women of his grandfather's day, Kublai's wives and daughters were an almost invisible presence. Kublai's original choice of successor was his son Zhenjin, who became the head of the Zhongshu Sheng and actively administered the dynasty according to Confucian fashion. Nomukhan, after returning from captivity in the Golden Horde, expressed resentment that Zhenjin had been made heir apparent, but he was banished to the north. An official proposed that Kublai should abdicate in favor of Zhenjin in 1285, a suggestion that angered Kublai, who refused to see Zhenjin. Zhenjin died soon afterwards in 1286, eight years before his father. Kublai regretted this and remained very close to his wife, Bairam (also known as Kokejin).

Kublai became increasingly despondent after the deaths of his favorite wife and his chosen heir Zhenjin. The failure of the military campaigns in Vietnam and Japan also haunted him. Kublai turned to food and drink for comfort, became grossly overweight, and suffered gout and diabetes. The emperor overindulged in alcohol and the traditional meat-rich Mongol diet, which may have contributed to his gout. Kublai sank into depression due to the loss of his family, his poor health and advancing age. Kublai tried every medical treatment available, from Korean shamans to Vietnamese doctors, and remedies and medicines, but to no avail. At the end of 1293, the emperor refused to participate in the traditional New Years' ceremony. Before his death, Kublai passed the seal of Crown Prince to Zhenjin's son Temür, who would become the next Khagan of the Mongol Empire and the second ruler of the Yuan dynasty. Seeking an old companion to comfort him in his final illness, the palace staff could choose only Bayan, more than 30 years his junior. Kublai weakened steadily, and on February 18, 1294, he died at the age of 78. Two days later, the funeral cortège took his body to the burial place of the khans in Mongolia.

Family

Wives and children

Kublai first married Tegulen but she died very early. Then he married Chabi of the Khongirad, who was his most beloved empress. After Chabi's death in 1281, Kublai married Chabi's young cousin, Nambui, presumably in accordance with Chabi's wish.[140]

Principal wives (first and second ordos):

- Tegülün Khatun (d. 1233) — of unknown parents; she is known to have been from Khongirad

- Dorji (b. c. 1233, d. 1263) — the director of the Secretariat and head of the Bureau of Military Affairs from 1261, but was sickly and died young.

- Empress Chabi (b. 1216, m. 1234, d. 1281) — daughter of Alchi Noyan (Anchen) from Khongirad.

- Crown Prince Zhenjin (1243 – 1285) — Prince of Yan (燕王)

- Manggala (c. 1249–1280) — Prince of Anxi (安西王)

- Nomughan (d. 1301) — Prince of Beiping (北平王)

- Kokechi (d.1273)- Prince of Yunnan

- Grand Princess of Zhao, Yuelie (赵国大長公主) — married to Ay Buqa, Prince of Zhao (趙王)

- Princess Ulujin (吾魯真公主) — married to Buqa from Ikires clan

- Princess Chalun (昌国大长公主) - married to Teliqian from Ikires clan

- Grand Princess of Lu, Öljei (鲁国长公主) — married to Ulujin Küregen from Khongirad clan, Prince of Lu

- Grand Princess of Lu, Nangiajin (鲁国大长公主) — married to Ulujin Küregen from Khongirad clan, Princess of Lu, then after Ulujin's death in 1278 to his brother Temür, and after Temür's death in 1290 to a third brother, Manzitai

- Princess Jeguk

- Empress Nambui (m. 1283) — daughter of Nachen, who was the brother of Empress Chabi

- Temuchi

Wives from third ordo:

- Empress Talahai (塔剌海皇后)

- Empress Nuhan (奴罕皇后)

Wives from fourth ordo:

- Empress Bayaujin (伯要兀真皇后) — daughter of Boraqchin of Bayauts

- Toghon — Prince of Zhennan (鎮南王)

- Empress Kökelün (阔阔伦皇后)

Concubines:

- Lady Babahan (八八罕妃子)

- Lady Sabuhu (撒不忽妃子)

- Qoruqchin Khatun — daughter of Qutuqu (brother of Toqto'a Beki) from Merkits

- Qoridai — Commander of Möngke in Tibet

- Dörbejin Khatun — from Dörben tribe

- Aqruqchi (d. 1306) — Prince of Xiping

- Hüshijin Khatun — daughter of Boroqul Noyan

- Kököchü (fl. 1313) — Prince of Ning (宁王)

- Ayachi (fl. 1324) — Commander of Hexi Corridor

- An unknown lady

- Qutluq Temür (fl. 1324)

- Asujin Khatun (阿速眞可敦)[141] — probably from Asud tribe

Poetry

Kublai was a prolific writer of Chinese poetry, although most of his works are now lost. Only one Chinese poem written by him is included in the Selection of Yuan Poetry (元詩選), titled 'Inspiration recorded while enjoying the ascent to Spring Mountain'. It was translated into Mongolian by the Inner Mongolian scholar B.Buyan in the same style as classical Mongolian poetry and transcribed into Cyrillic by Ya.Ganbaatar. It is said that once in spring Kublai Khan went to worship at a Buddhist temple at the Summer Palace in western Khanbaliq (Beijing) and on his way back ascended Longevity Hill (Tumen Nast Uul in Mongolian), where he was filled with inspiration and wrote this poem.[142]

| Inspiration recorded while enjoying the ascent to Spring Mountain (陟玩春山記興) | ||

|---|---|---|

時膺韶景陟蘭峰 |

Shí yīng sháo jǐng zhì lán fēng; | |

This is translated:

Havar tsagiin nairamduu uliral dor anhilam uulnaa avirlaa |

I ascended on Fragrant Hill in the friendly season of spring |

Legacy

Kublai's seizure of power in 1260 pushed the Mongol Empire into a new direction. Despite the controversy surrounding his accession, which accelerated the disunity of the Mongols, Kublai's willingness to formalize the Mongol-ruled realm's identification as China[10] brought the Mongol Empire to international attention. Kublai and his predecessors' conquests were largely responsible for re-creating a unified, militarily powerful China. Yuan rule of Tibet, Manchuria and Mongolia from a capital at modern-day Beijing set a precedent for the Qing dynasty's expansion into Inner Asia.[143]

In popular culture

- Kublai and Shangdu or Xanadu are the subject of various later artworks, including the English Romantic Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem "Kubla Khan", in which Coleridge makes Xanadu a symbol of mystery and splendor.

- In the 1938 film The Adventures of Marco Polo, George Barbier plays the role of Kublai Khan.

- Kublai's summer capital of Xanadu (also known as Shangdu) is the namesake for the palace in which Charles Foster Kane lives in the film, Citizen Kane (1941)

- Kabli Khan, a 1963 Indian Hindi-language musical action film by K. Amarnath which stars Ajit Khan in the titular role, presents a fictionalized narrative of a ruler seemingly based on Kublai Khan.[144]

- Kublai Khan is referenced in the Rush song "Xanadu", on their 1977 album A Farewell To Kings.

- Kublai Khan is referenced in the Frankie Goes To Hollywood song "Welcome to the Pleasuredome (song)", on their 1984 album of the same name.

- Kublai Khan named a heavy metal band formed in Sherman, Texas , since 2009. Check disambiguation.

- Kublai Khan is portrayed by Ying Ruocheng in the 1982 miniseries Marco Polo.

- Kublai Khan is a character played by Martin Miller in the serial Marco Polo in the first series of British sci-fi show ‘’Doctor Who’’.

- Kublai Khan is portrayed by Kim Myeong-Kuk in the 2012 Korean television series God of War.

- Kublai Khan is portrayed by Hu Jun in the 2013 Chinese television series The Legend of Kublai Khan.

- Kublai Khan plays a significant role in the 2014 Netflix production Marco Polo, in which he is depicted by Benedict Wong.

- The Government of Mongolia celebrated Kublai Khan's 800th birthday on 15 September 2015 to honour and value his contribution to Mongolian history and promote research works related to Mongolian history.[145][146]

- Kublai Khan plays a role in Jin Yong's work The Return of the Condor Heroes.

- Kublai Khan is also mentioned in the game Ghost of Tsushima as the cousin of the main villain Khotun Khan

- Kublai Khan is featured as a leader in the game Civilization VI, with players having the option to use him to lead either Mongolia or China.

- A number one famous Malaysian history genre novelist, Abdul Latip Talib wrote a Malay biography and fictional novel about Kublai Khan titled, Kublai Khan: Pengasas Dinasti Yuan

- Kublai Khan's dialogues with Marco Polo are the subject of Italo Calvino's novel Invisible Cities.

See also

- Division of the Mongol Empire

- History of Beijing

- Kaidu–Kublai war

- List of Yuan emperors

- List of Mongol rulers

- List of Chinese monarchs

- Temür Khan

- Toluid Civil War

References

Notes

- Decades before Kublai announced the dynastic name "Great Yuan" in 1271, khagans (Great Khans) of the "Great Mongol State" (Yeke Mongγol Ulus) already started to use the Chinese title of Emperor (Chinese: 皇帝; pinyin: Huángdì) practically in the Chinese language since the enthronement of Temüjin as "Genghis Emperor" (成吉思皇帝; 'Chéngjísī Huángdì') in Spring 1206.[1]

- Dates given here are in the Julian calendar. They are not in the proleptic Gregorian calendar.

- The defeat of the Song dynasty at the Battle of Yamen in 19 March is considered the start of Kubilai Khan's rule over the whole of China proper.

- Also known as Qubilai or Kübilai; Mongolian: Хубилай, romanized: Khubilai ; Mongolian script: ᠬᠤᠪᠢᠯᠠᠢ; Chinese: 忽必烈; pinyin: Hūbìliè

- As per modern historiographical norm, the "Yuan dynasty" in this article refers exclusively to the realm based in Dadu (present-day Beijing). However, the Han-style dynastic name "Great Yuan" (大元) as proclaimed by Kublai in 1271, as well as the claim to Chinese political orthodoxy were meant to be applied to the entire Mongol Empire.[2][3][4] In spite of this, "Yuan dynasty" is rarely used in the broad sense of the definition by modern scholars due to the de facto disintegrated nature of the Mongol Empire.

Citations

- "太祖本纪 [Chronicle of Taizu]". 《元史》 [History of Yuan] (in Literary Chinese).

元年丙寅,帝大会诸王群臣,建九斿白旗,即皇帝位于斡难河之源,诸王群臣共上尊号曰成吉思皇帝["Genghis Huangdi"]。

- Robinson, David (2019). In the Shadow of the Mongol Empire: Ming China and Eurasia. p. 50. ISBN 9781108482448. Archived from the original on 2022-03-12. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- Robinson, David (2009). Empire's Twilight: Northeast Asia Under the Mongols. p. 293. ISBN 9780674036086. Archived from the original on 2022-03-08. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- Brook, Timothy; Walt van Praag, Michael van; Boltjes, Miekn (2018). Sacred Mandates: Asian International Relations since Chinggis Khan. p. 45. ISBN 9780226562933. Archived from the original on 2022-03-11. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 893.

- Marshall, Robert. Storm from the South: from Genghis Khan to Khubilai Khan. p. 224.

- Borthwick, Mark (2007). Pacific Century. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4355-6.

- Howorth, H. H. The History of the Mongols. Vol. II. p. 288.

- Man 2007

- Kublai (18 December 1271), 《建國號詔》 [Edict to Establish the Name of the State], 《元典章》[Statutes of Yuan] (in Classical Chinese)

- Chen, Yuan Julian (2014). ""Legitimation Discourse and the Theory of the Five Elements in Imperial China." Journal of Song-Yuan Studies 44 (2014): 325–364". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 44 (1): 325–364. doi:10.1353/sys.2014.0000. S2CID 147099574. Archived from the original on 2019-10-11. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- Weatherford, Jack. The Secret History of the Mongol Queens. p. 135.

- Man 2007, p. 37

- Haw, Stephen G. Marco Polo's China. p. 33.

- Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis C., eds. (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5. Archived from the original on 2016-06-17. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Man 2007, p. 79

- Atwood 2004, p. 613

- Du Yuting; Chen Lifan (1989). "Did Kublai Khan's Conquest of the Dali Kingdom Give Rise to the Mass Migration of the Thai People to the South?" (free). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Heritage Trust. JSS Vol. 77.1c (digital): image. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Weatherford 2005, p. 186

- Gazangjia. Tibetan Religions. p. 115.

- Sun Kokuan. Yu chi and Southern Daoism during the Yuan period, in China under Mongol rule. pp. 212–253.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 502.

- Bagchi, Prabodh Chandra (2011). India and China. Anthem Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-93-80601-17-5. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Nag, Kalidas. Greater India. p. 216.

- Mah, Adeline Yen (2008). China: Land of Dragons and Emperors. Random House Children's Books. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-375-89099-4. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Man 2007, p. 102

- Atwood 2004, p. 458

- Whiting, Marvin C. Imperial Chinese Military History: 8000 BC – 1912 AD. p. 394.

- Man 2007, p. 109

- Weatherford 2005, p. 120

- Салих Закиров, Дипломатические отношения Золотой орды с Египтом

- al-Din, Rashid. Universal History.

- Rashid al-Din, ibid

- Howorth, H. H. History of the Mongols section: "Berke khan"

- H. H. Howorth History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: Part 2. The So-Called Tartars of Russia and Central Asia. Division 1

- Otsahi Matsuwo Khubilai Kan

- Prawdin, Michael. Mongol Empire and its legacy. p. 302.

- Biran, Michael. Qaidu and the Rise of the Independent Mongol State In Central Asia, p. 63

- Saunders 2001, pp. 130–132

- Craughwell, Thomas J. (2010). The Rise and Fall of the Second Largest Empire in History: How Genghis Khan's Mongols Almost Conquered the World. Fair Winds Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-1616738518. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Grousset 1970, p. 294

- Vernadsky, G. V. The Mongols and Russia. p. 155.

- Q. Pachymeres, Bk 5, ch.4 (Bonn ed. 1,344)

- Rashid al-Din

- Man 2007, p. 74

- The History of the Yuan Dynasty

- Sh.Tseyen-Oidov – Ibid, p. 64

- Man 2007, p. 207

- Grousset 1970, p. 297

- Allsen, Thomas T. The Princes of the Left Hand: An Introduction to the History of the Rulus of Orda in the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries. p. 21.

- Eurasia Archivum Eurasiae medii aevi, p. 21

- Weatherford 2005, p. 195

- Vernadsky, G. V. The Mongols and Russia. pp. 344–366.

- Henryk Samsonowicz, Maria Bogucka A Republic of Nobles, p. 179

- Vernadsky, G. V. A History of Russia (New, Revised ed.).

- Rossabi 1988, p. 115

- Man 2007, p. 231

- Phillips, J. R. S. The Medieval Expansion of Europe. p. 122.

- Grousset 1970, p. 304

- Rossabi 1988, p. 76

- Grant, R. G. (2017). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of History. Book Sales. ISBN 978-0785835530. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- "The Mongols and Tibet – A historical assessment of relations between the Mongol Empire and Tibet". Archived from the original on April 29, 2009.

- Rossabi 1988, p. 247

- Theobald, Ulrich. "Yuan Empire Geography (www.chinaknowledge.de)". www.chinaknowledge.de. Archived from the original on 2008-06-05. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- Enkhbold, Enerelt (2019). "The role of the ortoq in the Mongol Empire in forming business partnerships". Central Asian Survey. 38 (4): 531–547. doi:10.1080/02634937.2019.1652799. S2CID 203044817.

- Cecilia Lee-fang Chien Salt and state, p. 25

- Weatherford 2005, p. 176

- Martinez, A. P. The use of Mint-output data in Historical research on the Western appanages. pp. 87–100.

- Weatherford 1997, p. 127

- de Rachewiltz, Igor; Chan, Hok-Lam; Ch'i-ch'ing, Hsiao; et al., eds. (1993). In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yüan Period. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 562. ISBN 978-3-447-03339-8. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp110_wuzong_emperor.pdf Archived 2016-12-20 at the Wayback Machine p. 15.

- Angela Schottenhammer (2008). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-3-447-05809-4. Archived from the original on 2019-07-03. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- Sen, Tansen. 2006. "The Yuan Khanate and India: Cross-cultural Diplomacy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries". Asia Major 19 (1/2). Academia Sinica: 317. Archived 2016-01-27 at the Wayback Machine JSTOR 41649921

- Lagerwey, John. Religion and Chinese society. p. xxi.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) p. 14. - Banning, B. Paul. "AAS Abstracts: China Session 45". Archived from the original on 2016-10-06.

- "AAS Abstracts: China Session 45". Archived from the original on 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2015-03-18. "Welcome to the US Petabox". Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) is/hOXhs - Wilson, Thomas A. "Cult of Confucius". Archived from the original on 2016-03-18. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- "Quzhou City Guides – China TEFL Network". 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- "Confucius Anniversary Celebrated". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 2015-09-14. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- Thomas Jansen; Thoralf Klein; Christian Meyer (2014). Globalization and the Making of Religious Modernity in China: Transnational Religions, Local Agents, and the Study of Religion, 1800–Present. Brill. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-90-04-27151-7. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Nation observes Confucius anniversary". China Daily. 2006-09-29. Archived from the original on 2016-01-08. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- Dillon, Michael (1999). China's Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1026-3. Archived from the original on 2022-03-27. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- Elverskog, Johan (2011). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0531-2. Archived from the original on 2022-03-27. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- Donald Daniel Leslie (1998). "The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims" (PDF). The Fifty-ninth George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-06-28..

- Mohammed Khamouch (April 2007). "1001 Years of Missing Martial Arts" (PDF). muslimheritage.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-11-02. Retrieved 2013-11-14.

- "Saudi Aramco World : Muslims in China: The History". archive.aramcoworld.com. Archived from the original on 2022-03-27. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Hitchens, Marilynn Giroux; Roupp, Heidi (2001). How to Prepare for SAT II: World history (2nd ed.). Barron's Educational Series. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7641-1385-7.

- Meuleman, Johan, ed. (2002). Islam in the Era of Globalization: Muslim Attitudes Towards Modernity and Identity. Routledge. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-135-78829-2. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Atwood 2004, p. 354

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica, p. 111

- Farquhar, David M. (1990). The Government of China Under Mongolian Rule: A Reference Guide. F. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden. p. 272. ISBN 978-3-515-05578-9. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Harrassowitz, Otto. Archivum Eurasiae medii aeivi [i.e. aevi]. p. 36.

- Atwood 2004, p. 264

- M. Kutlukov, "Mongol Rule in Eastern Turkestan". Article in collection Tataro-Mongols in Asia and Europe. Moscow, 1970

- Atwood 2004, p. 403

- Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis C., eds. (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5. Archived from the original on 2016-06-17. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Mackerras, Colin (1994). China's Minorities: Integration and Modernization in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-19-585988-1. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Ballard, George Alexander (1921). The Influence of the Sea on the Political History of Japan. E.P. Dutton. p. 21.

- Schirokauer, Conrad. A Brief History of Chinese and Japanese civilizations. p. 211.

- (Miya 2006; Miya 2007)

- Atwood 2004, p. 434

- History of Yuan 『元史』 卷十二 本紀第十二 世祖九 至元十九年七月壬戌(August 9, 1282)「高麗国王請、自造船百五十艘、助征日本。」

- Ж.Ганболд, Т.Мөнхцэцэг, Д.Наран, А.Пунсаг-Монголын Юань улс, хуудас 122

- 『高麗史』 巻八十七 表巻第二「十月、金方慶與元元帥忽敦洪茶丘等征日本、至壹岐戰敗、軍不還者萬三千五百餘人」

- "Shipwreck may be part of Kublai Khan's lost fleet". October 25, 2011. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011.

- Nicolle, David The Mongol Warlords

- Baldanza 2016, p. 17.

- Weatherford 2005, p. 212.

- Hucker 1975, p. 285.

- Aymonier 1893, p. 16.

- Haw 2013, pp. 361–371.

- Baldanza 2016, p. 19.

- Bulliet et al. 2014, p. 336.

- Baldanza 2016, p. 17-26.

- Grousset 1970, p. 291

- Atwood 2004, p. 72

- George, Daniel (1981). History of South East Asia. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 134. ISBN 9781349165216. Archived from the original on 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Carter, Ron (1987). The Spread of Civilization. Macdonald. p. 32. ISBN 9780382064081. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- McCabe, Robert Karr (1967). Storm Over Asia: China and Southeast Asia: Thrust and Response. University of Michigan: New American Library. p. 14. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Audric, John (1972). Angkor and the Khmer Empire. R. Hale. p. 115. ISBN 9780709129455. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Mendis, Vernon LB (1981). Currents of Asian History. University of Michigan: Lake House Investments. p. 389. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Coedes, George (1983). The Making of South East Asia. University of California Press. p. 193. ISBN 9780520050617. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (1977). A History of China. University of California Press. p. 239. ISBN 9780520032682. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Pandey, Rajbali (1971). Svargīya Padmabhūshaṇa Paṇḍita Kuñjīlāla Dube smr̥ti-grantha. University of Michigan: Sva. Padmabhūshaṇa Paṇḍita Kuñjīlāla Dube Smr̥ti-Grantha Samiti. p. 94. Archived from the original on 2021-09-28. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Tudisco, AJ (1967). Asia Emerges. University of California: Diablo Press. p. 316. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa By Timothy Insoll Page 66

- Medieval History, Volume 2 by Headstart History: "Marco Polo , who relates how the new Mongol overlord of China , Kublai Khan , sent envoys to Mogadishu on the Somali coast to treat for the release of a previous emissary."

- Schinz, Alfred. The Magic Square. p. 291.

- Lall, Kesar. A Nepalese Miscellany. p. 32.

- Paul Pelliot, Notes on Marco Polo, p. 85

- Anne Elizabeth McLaren, Chinese popular culture and Ming chantefables, p. 244

- Mullie, E. P. J. De Mongoolse prins Nayan. pp. 9–11.

- Pelliot, P. (1963) Notes on Marco Polo, Vol. I, Imprimerie Nationale, Paris, pp. 354–355

- Igor de Rachewiltz, In the service of the Khan: eminent personalities of the early Mongol-Yüan period, p. 599

- Grousset 1970, p. 293

- Amitai-Preiss & Morgan 2000, p. 33

- Rashid al-Din JT, I/2 in TVOIRA

- Amitai-Preiss & Morgan 2000, p. 43

- Man 2004, p. 394

- "高麗史/卷八十九 - 维基文库,自由的图书馆". zh.wikisource.org (in Chinese). Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- Ya.Ganbaatar. Yuan ulsiin uyiin mongolchuudiin hyatadaar bichsen shulgiin songomol (Selection of Chinese poems written by Mongolians during the Yuan dynasty), Ulan Bator, 2007 p. 15

- Atwood 2004, p. 611

- "Kabli Khan". Eros Now. Archived from the original on 2021-05-27. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- "Mongolia commemorates 800th anniversary of Kublai Khan". www.infomongolia.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

- "Divided Mongolias find unity in common ancestor Kublai". 21 September 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015 – via Japan Times Online.

Sources

- Aymonier, Etienne (1893). The History of Tchampa (the Cyamba of Marco Polo, Now Annam Or Cochin-China). Oriental University Institute.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-53131-0.

- Bulliet, Richard; Crossley, Pamela; Headrick, Daniel; Hirsch, Steven; Johnson, Lyman (2014). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781285965703.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2013). "The deaths of two Khaghans: a comparison of events in 1242 and 1260". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 76 (3): 361–371. doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000475. JSTOR 24692275.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1975). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804723534.

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven; Morgan, David O., eds. (2000). The Mongol Empire and Its Legacy. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11946-8. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- Chan, Hok-Lam. 1997. "A Recipe to Qubilai Qa'an on Governance: The Case of Chang Te-hui and Li Chih". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 7 (2). Cambridge University Press: 257–83. JSTOR 25183352.

- Clements, Jonathan (2010). A Brief History of Khubilai Khan. Philadelphia: Running Press. ISBN 978-0-7624-3987-4.

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death and Resurrection. London; New York: Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0-593-05044-6.

- Man, John (2007). Kublai Khan: The Mongol King Who Remade China. London; New York: Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0-553-81718-8.

- Morgan, David (1986). The Mongols. New York: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-17563-6.

- Rossabi, Morris (1988). Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06740-0.

- Saunders, J. J. (2001) [1971]. The History of the Mongol Conquests. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1766-7. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Weatherford, Jack (1997). The History of Money. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-55674-5. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Weatherford, Jack (2005). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-609-80964-8. Archived from the original on 2022-05-02. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

Further reading

- Lanchester, John, "The Invention of Money: How the heresies of two bankers became the basis of our modern economy", The New Yorker, 5 & 12 August 2019, pp. 28–31. "One of the things that astonished Marco Polo most [in China] was paper money, introduced by Kublai [Khan] in 1260." (p. 28.)

External links

- Inflation under Kublai

- Relics of the Kamikaze (Archaeological Institute of America)