Heavy metal music

Heavy metal (or simply metal) is a genre of rock music that developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s, largely in the United Kingdom and United States.[2] With roots in blues rock, psychedelic rock and acid rock, heavy metal bands developed a thick, monumental sound characterized by distorted guitars, extended guitar solos, emphatic beats and loudness.

| Heavy metal | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Metal |

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Late 1960s, United Kingdom and United States |

| Derivative forms | Grunge[1] |

| Subgenres | |

| |

| Fusion genres | |

| |

| Regional scenes | |

| |

| Local scenes | |

Birmingham

| |

| Other topics | |

| |

In 1968, three of the genre's most famous pioneers, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple, were founded.[3] Though they came to attract wide audiences, they were often derided by critics. Several American bands modified heavy metal into more accessible forms during the 1970s: the raw, sleazy sound and shock rock of Alice Cooper and Kiss; the blues-rooted rock of Aerosmith; and the flashy guitar leads and party rock of Van Halen.[4] During the mid-1970s, Judas Priest helped spur the genre's evolution by discarding much of its blues influence,[5][6] while Motörhead introduced a punk rock sensibility and an increasing emphasis on speed. Beginning in the late 1970s, bands in the new wave of British heavy metal such as Iron Maiden and Saxon followed in a similar vein. By the end of the decade, heavy metal fans became known as "metalheads" or "headbangers". The lyrics and performances are usually associated with aggression and machismo,[7] an issue that has sometimes led to accusations of misogyny.

During the 1980s, glam metal became popular with groups such as Bon Jovi, Mötley Crüe and Poison. Meanwhile, however, underground scenes produced an array of more aggressive styles: thrash metal broke into the mainstream with bands such as Metallica, Slayer, Megadeth, and Anthrax, while other extreme subgenres such as death metal and black metal remain subcultural phenomena. Since the mid-1990s, popular styles have expanded the definition of the genre. These include groove metal and nu metal, the latter of which often incorporates elements of grunge and hip hop.

Characteristics

Heavy metal is traditionally characterized by loud distorted guitars, emphatic rhythms, dense bass-and-drum sound, and vigorous vocals. Heavy metal subgenres variously emphasize, alter, or omit one or more of these attributes. The New York Times critic Jon Pareles writes, "In the taxonomy of popular music, heavy metal is a major subspecies of hard-rock—the breed with less syncopation, less blues, more showmanship and more brute force."[8] The typical band lineup includes a drummer, a bassist, a rhythm guitarist, a lead guitarist, and a singer, who may or may not be an instrumentalist. Keyboard instruments are sometimes used to enhance the fullness of the sound.[9] Deep Purple's Jon Lord played an overdriven Hammond organ. In 1970, John Paul Jones used a Moog synthesizer on Led Zeppelin III; by the 1990s, in "almost every subgenre of heavy metal" synthesizers were used.[10]

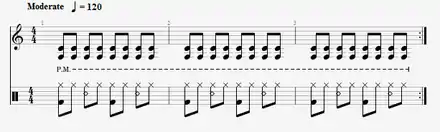

The electric guitar and the sonic power that it projects through amplification has historically been the key element in heavy metal.[11] The heavy metal guitar sound comes from a combined use of high volumes and heavy fuzz.[12] For classic heavy metal guitar tone, guitarists maintain gain at moderate levels, without excessive preamp or pedal distortion, to retain open spaces and air in the music; the guitar amplifier is turned up loud to produce the characteristic "punch and grind".[13] Thrash metal guitar tone has scooped mid-frequencies and tightly compressed sound with multiple bass frequencies.[13] Guitar solos are "an essential element of the heavy metal code ... that underscores the significance of the guitar" to the genre.[14] Most heavy metal songs "feature at least one guitar solo",[15] which is "a primary means through which the heavy metal performer expresses virtuosity".[16] Some exceptions are nu metal and grindcore bands, which tend to omit guitar solos.[17] With rhythm guitar parts, the "heavy crunch sound in heavy metal ... [is created by] palm muting" the strings with the picking hand and using distortion.[18] Palm muting creates a tighter, more precise sound and it emphasizes the low end.[19]

The lead role of the guitar in heavy metal often collides with the traditional "frontman" or bandleader role of the vocalist, creating a musical tension as the two "contend for dominance" in a spirit of "affectionate rivalry".[9] Heavy metal "demands the subordination of the voice" to the overall sound of the band. Reflecting metal's roots in the 1960s counterculture, an "explicit display of emotion" is required from the vocals as a sign of authenticity.[20] Critic Simon Frith claims that the metal singer's "tone of voice" is more important than the lyrics.[21]

The prominent role of the bass is also key to the metal sound, and the interplay of bass and guitar is a central element. The bass provides the low-end sound crucial to making the music "heavy".[22] The bass plays a "more important role in heavy metal than in any other genre of rock".[23] Metal basslines vary widely in complexity, from holding down a low pedal point as a foundation to doubling complex riffs and licks along with the lead or rhythm guitars. Some bands feature the bass as a lead instrument, an approach popularized by Metallica's Cliff Burton with his heavy emphasis on bass solos and use of chords while playing the bass in the early 1980s.[24] Lemmy of Motörhead often played overdriven power chords in his bass lines.[25]

The essence of heavy metal drumming is creating a loud, constant beat for the band using the "trifecta of speed, power, and precision".[26] Heavy metal drumming "requires an exceptional amount of endurance", and drummers have to develop "considerable speed, coordination, and dexterity ... to play the intricate patterns" used in heavy metal.[27] A characteristic metal drumming technique is the cymbal choke, which consists of striking a cymbal and then immediately silencing it by grabbing it with the other hand (or, in some cases, the same striking hand), producing a burst of sound. The metal drum setup is generally much larger than those employed in other forms of rock music.[22] Black metal, death metal and some "mainstream metal" bands "all depend upon double-kicks and blast beats".[28]

In live performance, loudness—an "onslaught of sound", in sociologist Deena Weinstein's description—is considered vital.[11] In his book, Metalheads, psychologist Jeffrey Arnett refers to heavy metal concerts as "the sensory equivalent of war".[29] Following the lead set by Jimi Hendrix, Cream and the Who, early heavy metal acts such as Blue Cheer set new benchmarks for volume. As Blue Cheer's Dick Peterson put it, "All we knew was we wanted more power."[30] A 1977 review of a Motörhead concert noted how "excessive volume in particular figured into the band's impact."[31] Weinstein makes the case that in the same way that melody is the main element of pop and rhythm is the main focus of house music, powerful sound, timbre, and volume are the key elements of metal. She argues that the loudness is designed to "sweep the listener into the sound" and to provide a "shot of youthful vitality".[11]

Heavy metal performers tended to be almost exclusively male[32] until at least the mid-1980s,[33] with some exceptions such as Girlschool.[32] However, by the 2010s, women were making more of an impact,[34][35] and PopMatters' Craig Hayes argues that metal "clearly empowers women".[36] In the sub-genres of symphonic and power metal, there has been a sizable number of bands that have had women as the lead singers; bands such as Nightwish, Delain, and Within Temptation have featured women as lead singers with men playing instruments.

Rhythm and tempo

The rhythm in metal songs is emphatic, with deliberate stresses. Weinstein observes that the wide array of sonic effects available to metal drummers enables the "rhythmic pattern to take on a complexity within its elemental drive and insistency".[22] In many heavy metal songs, the main groove is characterized by short, two-note or three-note rhythmic figures—generally made up of 8th or 16th notes. These rhythmic figures are usually performed with a staccato attack created by using a palm-muted technique on the rhythm guitar.[37]

Brief, abrupt, and detached rhythmic cells are joined into rhythmic phrases with a distinctive, often jerky texture. These phrases are used to create rhythmic accompaniment and melodic figures called riffs, which help to establish thematic hooks. Heavy metal songs also use longer rhythmic figures such as whole note- or dotted quarter note-length chords in slow-tempo power ballads. The tempos in early heavy metal music tended to be "slow, even ponderous".[22] By the late 1970s, however, metal bands were employing a wide variety of tempos. In the 2000s decade, metal tempos range from slow ballad tempos (quarter note = 60 beats per minute) to extremely fast blast beat tempos (quarter note = 350 beats per minute).[27]

Harmony

One of the signatures of the genre is the guitar power chord.[38] In technical terms, the power chord is relatively simple: it involves just one main interval, generally the perfect fifth, though an octave may be added as a doubling of the root. When power chords are played on the lower strings at high volumes and with distortion, additional low frequency sounds are created, which add to the "weight of the sound" and create an effect of "overwhelming power".[39] Although the perfect fifth interval is the most common basis for the power chord,[40] power chords are also based on different intervals such as the minor third, major third, perfect fourth, diminished fifth, or minor sixth.[41] Most power chords are also played with a consistent finger arrangement that can be slid easily up and down the fretboard.[42]

Typical harmonic structures

Heavy metal is usually based on riffs created with three main harmonic traits: modal scale progressions, tritone and chromatic progressions, and the use of pedal points. Traditional heavy metal tends to employ modal scales, in particular the Aeolian and Phrygian modes.[43] Harmonically speaking, this means the genre typically incorporates modal chord progressions such as the Aeolian progressions I-♭VI-♭VII, I-♭VII-(♭VI), or I-♭VI-IV-♭VII and Phrygian progressions implying the relation between I and ♭II (I-♭II-I, I-♭II-III, or I-♭II-VII for example). Tense-sounding chromatic or tritone relationships are used in a number of metal chord progressions.[44][45] In addition to using modal harmonic relationships, heavy metal also uses "pentatonic and blues-derived features".[46]

The tritone, an interval spanning three whole tones—such as C to F#—was considered extremely dissonant and unstable by medieval and Renaissance music theorists. It was nicknamed the diabolus in musica—"the devil in music".[47]

Heavy metal songs often make extensive use of pedal point as a harmonic basis. A pedal point is a sustained tone, typically in the bass range, during which at least one foreign (i.e., dissonant) harmony is sounded in the other parts.[48] According to Robert Walser, heavy metal harmonic relationships are "often quite complex" and the harmonic analysis done by metal players and teachers is "often very sophisticated".[49] In the study of heavy metal chord structures, it has been concluded that "heavy metal music has proved to be far more complicated" than other music researchers had realized.[46]

Relationship with classical music

Robert Walser stated that, alongside blues and R&B, the "assemblage of disparate musical styles known ... as 'classical music'" has been a major influence on heavy metal since the genre's earliest days. Also that metal's "most influential musicians have been guitar players who have also studied classical music. Their appropriation and adaptation of classical models sparked the development of a new kind of guitar virtuosity [and] changes in the harmonic and melodic language of heavy metal."[50]

In an article written for Grove Music Online, Walser stated that the "1980s brought on ... the widespread adaptation of chord progressions and virtuosic practices from 18th-century European models, especially Bach and Antonio Vivaldi, by influential guitarists such as Ritchie Blackmore, Marty Friedman, Jason Becker, Uli Jon Roth, Eddie Van Halen, Randy Rhoads and Yngwie Malmsteen".[51] Kurt Bachmann of Believer has stated that "If done correctly, metal and classical fit quite well together. Classical and metal are probably the two genres that have the most in common when it comes to feel, texture, creativity."[52]

Although a number of metal musicians cite classical composers as inspiration, classical and metal are rooted in different cultural traditions and practices—classical in the art music tradition, metal in the popular music tradition. As musicologists Nicolas Cook and Nicola Dibben note, "Analyses of popular music also sometimes reveal the influence of 'art traditions'. An example is Walser's linkage of heavy metal music with the ideologies and even some of the performance practices of nineteenth-century Romanticism. However, it would be clearly wrong to claim that traditions such as blues, rock, heavy metal, rap or dance music derive primarily from "art music'."[53]

Lyrical themes

According to David Hatch and Stephen Millward, Black Sabbath and the numerous heavy metal bands that they inspired have concentrated lyrically "on dark and depressing subject matter to an extent hitherto unprecedented in any form of pop music". They take as an example Sabbath's second album Paranoid (1970), which "included songs dealing with personal trauma—'Paranoid' and 'Fairies Wear Boots' (which described the unsavoury side effects of drug-taking)—as well as those confronting wider issues, such as the self-explanatory 'War Pigs' and 'Hand of Doom'."[54] Deriving from the genre's roots in blues music, sex is another important topic—a thread running from Led Zeppelin's suggestive lyrics to the more explicit references of glam metal and nu metal bands.[55]

The thematic content of heavy metal has long been a target of criticism. According to Jon Pareles, "Heavy metal's main subject matter is simple and virtually universal. With grunts, moans and subliterary lyrics, it celebrates ... a party without limits ... [T]he bulk of the music is stylized and formulaic."[8] Music critics have often deemed metal lyrics juvenile and banal, and others[56] have objected to what they see as advocacy of misogyny and the occult. During the 1980s, the Parents Music Resource Center petitioned the U.S. Congress to regulate the popular music industry due to what the group asserted were objectionable lyrics, particularly those in heavy metal songs.[57] Andrew Cope states that claims that heavy metal lyrics are misogynistic are "clearly misguided" as these critics have "overlook[ed] the overwhelming evidence that suggests otherwise".[58] Music critic Robert Christgau called metal "an expressive mode [that] it sometimes seems will be with us for as long as ordinary white boys fear girls, pity themselves, and are permitted to rage against a world they'll never beat".[59]

Heavy metal artists have had to defend their lyrics in front of the U.S. Senate and in court. In 1985, Twisted Sister frontman Dee Snider was asked to defend his song "Under the Blade" at a U.S. Senate hearing. At the hearing, the PMRC alleged that the song was about sadomasochism and rape; Snider stated that the song was about his bandmate's throat surgery.[60] In 1986, Ozzy Osbourne was sued over the lyrics of his song "Suicide Solution".[61] A lawsuit against Osbourne was filed by the parents of John McCollum, a depressed teenager who committed suicide allegedly after listening to Osbourne's song. Osbourne was not found to be responsible for the teen's death.[62] In 1990, Judas Priest was sued in American court by the parents of two young men who had shot themselves five years earlier, allegedly after hearing the subliminal statement "do it" in the band's cover of the song Better by You, Better than Me.[63] While the case attracted a great deal of media attention, it was ultimately dismissed.[57] In 1991, UK police seized death metal records from the British record label Earache Records, in an "unsuccessful attempt to prosecute the label for obscenity".[64]

In some predominantly Muslim countries, heavy metal has been officially denounced as a threat to traditional values. In countries such as Morocco, Egypt, Lebanon, and Malaysia, there have been incidents of heavy metal musicians and fans being arrested and incarcerated.[65] In 1997, the Egyptian police jailed many young metal fans and they were accused of "devil worship" and blasphemy, after police found metal recordings during searches of their homes.[64] In 2013, Malaysia banned Lamb of God from performing in their country, on the grounds that the "band's lyrics could be interpreted as being religiously insensitive" and blasphemous.[66] Some people considered heavy metal music to being a leading factor for mental health disorders, and thought that heavy metal fans were more likely to suffer with a poor mental health, but study has proven that this is not true and the fans of this music have a lower or similar percentage of people suffering from poor mental health.[67]

Image and fashion

For many artists and bands, visual imagery plays a large role in heavy metal. In addition to its sound and lyrics, a heavy metal band's image is expressed in album cover art, logos, stage sets, clothing, design of instruments, and music videos.[68]

Down-the-back long hair is the "most crucial distinguishing feature of metal fashion".[69] Originally adopted from the hippie subculture, by the 1980s and 1990s heavy metal hair "symbolised the hate, angst and disenchantment of a generation that seemingly never felt at home", according to journalist Nader Rahman. Long hair gave members of the metal community "the power they needed to rebel against nothing in general".[70]

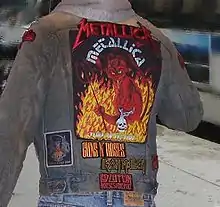

The classic uniform of heavy metal fans consists of light colored, ripped, frayed or torn blue jeans, black T-shirts, boots, and black leather or denim jackets. Deena Weinstein writes, "T-shirts are generally emblazoned with the logos or other visual representations of favorite metal bands."[71] In the 1980s, a range of sources, from punk and goth music to horror films, influenced metal fashion.[72] Many metal performers of the 1970s and 1980s used radically shaped and brightly colored instruments to enhance their stage appearance.[73][74]

Fashion and personal style was especially important for glam metal bands of the era. Performers typically wore long, dyed, hairspray-teased hair (hence the nickname, "hair metal"); makeup such as lipstick and eyeliner; gaudy clothing, including leopard-skin-printed shirts or vests and tight denim, leather, or spandex pants; and accessories such as headbands and jewelry.[73] Pioneered by the heavy metal act X Japan in the late 1980s, bands in the Japanese movement known as visual kei—which includes many nonmetal groups—emphasize elaborate costumes, hair, and makeup.[75]

Physical gestures

Many metal musicians when performing live engage in headbanging, which involves rhythmically beating time with the head, often emphasized by long hair. The il cornuto, or devil horns, hand gesture was popularized by vocalist Ronnie James Dio while with Black Sabbath and Dio.[45] Although Gene Simmons of Kiss claims to have been the first to make the gesture on the 1977 Love Gun album cover, there is speculation as to who started the phenomenon.[76]

Attendees of metal concerts do not dance in the usual sense. It has been argued that this is due to the music's largely male audience and "extreme heterosexualist ideology". Two primary body movements used are headbanging and an arm thrust that is both a sign of appreciation and a rhythmic gesture.[77] The performance of air guitar is popular among metal fans both at concerts and listening to records at home.[78] According to Deena Weinstein, thrash metal concerts have two elements that are not part of the other metal genres: moshing and stage diving, which "were imported from the punk/hardcore subculture".[79] Weinstein states that moshing participants bump and jostle each other as they move in a circle in an area called the "pit" near the stage. Stage divers climb onto the stage with the band and then jump "back into the audience".[79]

Fan subculture

It has been argued that heavy metal has outlasted many other rock genres largely due to the emergence of an intense, exclusionary, strongly masculine subculture.[80] While the metal fan base is largely young, white, male, and blue-collar, the group is "tolerant of those outside its core demographic base who follow its codes of dress, appearance, and behavior".[81] Identification with the subculture is strengthened not only by the group experience of concert-going and shared elements of fashion, but also by contributing to metal magazines and, more recently, websites.[82] Attending live concerts in particular has been called the "holiest of heavy metal communions."[83]

The metal scene has been characterized as a "subculture of alienation", with its own code of authenticity.[84] This code puts several demands on performers: they must appear both completely devoted to their music and loyal to the subculture that supports it; they must appear uninterested in mainstream appeal and radio hits; and they must never "sell out".[85] Deena Weinstein states that for the fans themselves, the code promotes "opposition to established authority, and separateness from the rest of society".[86]

Musician and filmmaker Rob Zombie observes, "Most of the kids who come to my shows seem like really imaginative kids with a lot of creative energy they don't know what to do with" and that metal is "outsider music for outsiders. Nobody wants to be the weird kid; you just somehow end up being the weird kid. It's kind of like that, but with metal you have all the weird kids in one place".[87] Scholars of metal have noted the tendency of fans to classify and reject some performers (and some other fans) as "poseurs" "who pretended to be part of the subculture, but who were deemed to lack authenticity and sincerity".[84][88]

Etymology

The origin of the term "heavy metal" in a musical context is uncertain. The phrase has been used for centuries in chemistry and metallurgy, where the periodic table organizes elements of both light and heavy metals (e.g., uranium). An early use of the term in modern popular culture was by countercultural writer William S. Burroughs. His 1962 novel The Soft Machine includes a character known as "Uranian Willy, the Heavy Metal Kid". Burroughs' next novel, Nova Express (1964), develops the theme, using heavy metal as a metaphor for addictive drugs: "With their diseases and orgasm drugs and their sexless parasite life forms—Heavy Metal People of Uranus wrapped in cool blue mist of vaporized bank notes—And The Insect People of Minraud with metal music".[89] Inspired by Burroughs' novels,[90] the term was used in the title of the 1967 album Featuring the Human Host and the Heavy Metal Kids by Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, which has been claimed to be its first use in the context of music.[91] The phrase was later lifted by Sandy Pearlman, who used the term to describe the Byrds for their supposed "aluminium style of context and effect", particularly on their album The Notorious Byrd Brothers (1968).[92]

Metal historian Ian Christe describes what the components of the term mean in "hippiespeak": "heavy" is roughly synonymous with "potent" or "profound", and "metal" designates a certain type of mood, grinding and weighted as with metal.[93] The word "heavy" in this sense was a basic element of beatnik and later countercultural hippie slang, and references to "heavy music"—typically slower, more amplified variations of standard pop fare—were already common by the mid-1960s, such as in reference to Vanilla Fudge. Iron Butterfly's debut album, released in early 1968, was titled Heavy. The first use of "heavy metal" in a song lyric is in reference to a motorcycle in the Steppenwolf song "Born to Be Wild", also released that year:[94] "I like smoke and lightning/Heavy metal thunder/Racin' with the wind/And the feelin' that I'm under."

An early documented use of the phrase in rock criticism appears in Sandy Pearlman's February 1967 Crawdaddy review of the Rolling Stones' Got Live If You Want It (1966), albeit as a description of the sound rather than as a genre: "On this album the Stones go metal. Technology is in the saddle—as an ideal and as a method."[95][nb 1] Another appears in the 11 May 1968, issue of Rolling Stone, in which Barry Gifford wrote about the album A Long Time Comin' by U.S. band Electric Flag: "Nobody who's been listening to Mike Bloomfield—either talking or playing—in the last few years could have expected this. This is the new soul music, the synthesis of white blues and heavy metal rock."[97] In the September 7, 1968, Seattle Daily Times, reviewer Susan Schwartz wrote that the Jimi Hendrix Experience "has a heavy-metals blues sound."[98] In January 1970 Lucian K. Truscott IV reviewing Led Zeppelin II for the Village Voice described the sound as "heavy" and made comparisons with Blue Cheer and Vanilla Fudge.[99]

Other early documented uses of the phrase are from reviews by critic Mike Saunders. In the 12 November 1970 issue of Rolling Stone, he commented on an album put out the previous year by the British band Humble Pie: "Safe as Yesterday Is, their first American release, proved that Humble Pie could be boring in lots of different ways. Here they were a noisy, unmelodic, heavy metal-leaden shit-rock band with the loud and noisy parts beyond doubt. There were a couple of nice songs ... and one monumental pile of refuse". He described the band's latest, self-titled release as "more of the same 27th-rate heavy metal crap".[100]

In a review of Sir Lord Baltimore's Kingdom Come in the May 1971 Creem, Saunders wrote, "Sir Lord Baltimore seems to have down pat most all the best heavy metal tricks in the book".[101] Creem critic Lester Bangs is credited with popularizing the term via his early 1970s essays on bands such as Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath.[102] Through the decade, heavy metal was used by certain critics as a virtually automatic putdown. In 1979, lead New York Times popular music critic John Rockwell described what he called "heavy-metal rock" as "brutally aggressive music played mostly for minds clouded by drugs",[103] and, in a different article, as "a crude exaggeration of rock basics that appeals to white teenagers".[104]

Coined by Black Sabbath drummer Bill Ward, "downer rock" was one of the earliest terms used to describe this style of music and was applied to acts such as Sabbath and Bloodrock. Classic Rock magazine described the downer rock culture revolving around the use of Quaaludes and the drinking of wine.[105] Later the term would be replaced by "heavy metal".[106]

Earlier on, as "heavy metal" emerged partially from heavy psychedelic rock, also known as acid rock, "acid rock" was often used interchangeably with "heavy metal" and "hard rock". "Acid rock" generally describes heavy, hard, or raw psychedelic rock. Musicologist Steve Waksman stated that "the distinction between acid rock, hard rock, and heavy metal can at some point never be more than tenuous",[107] while percussionist John Beck defined "acid rock" as synonymous with hard rock and heavy metal.[108]

Apart from "acid rock", the terms "heavy metal" and "hard rock" have often been used interchangeably, particularly in discussing bands of the 1970s, a period when the terms were largely synonymous.[109] For example, the 1983 Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll includes this passage: "known for its aggressive blues-based hard-rock style, Aerosmith was the top American heavy-metal band of the mid-Seventies".[110]

"The term 'heavy metal' is self-defeating," remarked Kiss bassist Gene Simmons. "When I think of heavy metal, I've always thought of elves and evil dwarves and evil princes and princesses. A lot of the Maiden and Priest records were real metal records. I sure as hell don't think Metallica's metal, or Guns N' Roses is metal, or Kiss is metal. It just doesn't deal with the ground opening up and little dwarves coming out riding dragons! You know, like bad Dio records."[111]

History

Antecedents: 1950s to late 1960s

Heavy metal's quintessential guitar style, built around distortion-heavy riffs and power chords, traces its roots to early 1950s Memphis blues guitarists such as Joe Hill Louis, Willie Johnson, and particularly Pat Hare,[112][113] who captured a "grittier, nastier, more ferocious electric guitar sound" on records such as James Cotton's "Cotton Crop Blues" (1954).[113] Other early influences include the late 1950s instrumentals of Link Wray, particularly "Rumble" (1958);[114] the early 1960s surf rock of Dick Dale, including "Let's Go Trippin'" (1961) and "Misirlou" (1962); and The Kingsmen's version of "Louie Louie" (1963) which became a garage rock standard.[115]

However, the genre's direct lineage begins in the mid-1960s. American blues music was a major influence on the early British rockers of the era. Bands like The Rolling Stones and The Yardbirds developed blues rock by recording covers of classic blues songs, often speeding up the tempos. As they experimented with the music, the UK blues-based bands—and the U.S. acts they influenced in turn—developed what would become the hallmarks of heavy metal; in particular, the loud, distorted guitar sound.[30] The Kinks played a major role in popularising this sound with their 1964 hit "You Really Got Me".[116]

In addition to The Kinks' Dave Davies, other guitarists such as The Who's Pete Townshend and The Yardbirds' Jeff Beck were experimenting with feedback.[117][118] Where the blues rock drumming style started out largely as simple shuffle beats on small kits, drummers began using a more muscular, complex, and amplified approach to match and be heard against the increasingly loud guitar.[119] Vocalists similarly modified their technique and increased their reliance on amplification, often becoming more stylized and dramatic. In terms of sheer volume, especially in live performance, The Who's "bigger-louder-wall-of-Marshalls" approach was seminal to the development of the later heavy metal sound.[120]

The combination of loud and heavy blues rock with psychedelic rock and acid rock formed much of the original basis for heavy metal.[121] The variant or subgenre of psychedelic rock often known as "acid rock" was particularly influential on heavy metal; acid rock is often defined as a heavier, louder, or harder variant of psychedelic rock,[122] or the more extreme side of the psychedelic rock genre, frequently containing a loud, improvised, and heavily distorted guitar-centered sound. Acid rock has been described as psychedelic rock at its "rawest and most intense," emphasizing the heavier qualities associated with both the positive and negative extremes of the psychedelic experience rather than only the idyllic side of psychedelia.[123] In contrast to more idyllic or whimsical pop psychedelic rock, American acid rock garage bands such as the 13th Floor Elevators epitomized the frenetic, heavier, darker and more psychotic psychedelic rock sound known as acid rock, a sound characterized by droning guitar riffs, amplified feedback, and guitar distortion, while the 13th Floor Elevators' sound in particular featured yelping vocals and "occasionally demented" lyrics.[124] Frank Hoffman notes that: "[Psychedelic rock] was sometimes referred to as 'acid rock'. The latter label was applied to a pounding, hard rock variant that evolved out of the mid-1960s garage-punk movement. ... When rock began turning back to softer, roots-oriented sounds in late 1968, acid-rock bands mutated into heavy metal acts."[125]

One of the most influential bands in forging the merger of psychedelic rock and acid rock with the blues rock genre was the British power trio Cream, who derived a massive, heavy sound from unison riffing between guitarist Eric Clapton and bassist Jack Bruce, as well as Ginger Baker's double bass drumming.[126] Their first two LPs, Fresh Cream (1966) and Disraeli Gears (1967), are regarded as essential prototypes for the future style of heavy metal. The Jimi Hendrix Experience's debut album, Are You Experienced (1967), was also highly influential. Hendrix's virtuosic technique would be emulated by many metal guitarists and the album's most successful single, "Purple Haze", is identified by some as the first heavy metal hit.[30] Vanilla Fudge, whose first album also came out in 1967, has been called "one of the few American links between psychedelia and what soon became heavy metal",[127] and the band has been cited as an early American heavy metal group.[128] On their self-titled debut album, Vanilla Fudge created "loud, heavy, slowed-down arrangements" of contemporary hit songs, blowing these songs up to "epic proportions" and "bathing them in a trippy, distorted haze."[127]

During the late 1960s, many psychedelic singers, such as Arthur Brown, began to create outlandish, theatrical and often macabre performances that influenced many metal acts.[129][130][131] The American psychedelic rock band Coven, who opened for early heavy metal influencers such as Vanilla Fudge and the Yardbirds, portrayed themselves as practitioners of witchcraft or black magic, using dark—Satanic or occult—imagery in their lyrics, album art, and live performances. Live shows consisted of elaborate, theatrical "Satanic rites". Coven's 1969 debut album, Witchcraft Destroys Minds & Reaps Souls, featured imagery of skulls, black masses, inverted crosses, and Satan worship, and both the album artwork and the band's live performances marked the first appearances in rock music of the sign of the horns, which would later become an important gesture in heavy metal culture.[132][133] At the same time in England, the band Black Widow were also among the first psychedelic rock bands to use occult and Satanic imagery and lyrics, though both Black Widow and Coven's lyrical and thematic influences on heavy metal were quickly overshadowed by the darker and heavier sounds of Black Sabbath.[132][133]

Origins: late 1960s and early 1970s

.jpg.webp)

Critics disagree over who can be thought of as the first heavy metal band. Most credit either Led Zeppelin or Black Sabbath, with American commentators tending to favour Led Zeppelin and British commentators tending to favour Black Sabbath, though many give equal credit to both. Deep Purple, the third band in what is sometimes considered the "unholy trinity" of heavy metal (Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, and Deep Purple), fluctuated between many rock styles until late 1969 when they took a heavy metal direction.[134] A few commentators—mainly American—argue for other groups including Iron Butterfly, Steppenwolf, Blue Cheer, or Vanilla Fudge as the first to play heavy metal.[135]

In 1968, the sound that would become known as heavy metal began to coalesce. That January, the San Francisco band Blue Cheer released a cover of Eddie Cochran's classic "Summertime Blues", from their debut album Vincebus Eruptum, that many consider the first true heavy metal recording.[136][137] The same month, Steppenwolf released its self-titled debut album, including "Born to Be Wild", which refers to "heavy metal thunder" in describing a motorcycle. In July, the Jeff Beck Group, whose leader had preceded Page as The Yardbirds' guitarist, released its debut record: Truth featured some of the "most molten, barbed, downright funny noises of all time," breaking ground for generations of metal ax-slingers.[138] In September, Page's new band, Led Zeppelin, made its live debut in Denmark (billed as The New Yardbirds).[139] The Beatles' self-titled double album, released in November, included "Helter Skelter", then one of the heaviest-sounding songs ever released by a major band.[140] The Pretty Things' rock opera S.F. Sorrow, released in December, featured "proto heavy metal" songs such as "Old Man Going" and "I See You".[141][142] Iron Butterfly's 1968 song "In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida" is sometimes described as an example of the transition between acid rock and heavy metal[143] or the turning point in which acid rock became "heavy metal",[144] and both Iron Butterfly's 1968 album In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida and Blue Cheer's 1968 album Vincebus Eruptum have been described as laying the foundation of heavy metal and greatly influential in the transformation of acid rock into heavy metal.[145]

In this counterculture period MC5, who began as part of the Detroit garage rock scene, developed a raw distorted style that has been seen as a major influence on the future sound of both heavy metal and later punk music.[146][147] The Stooges also began to establish and influence a heavy metal and later punk sound, with songs such as "I Wanna Be Your Dog", featuring pounding and distorted heavy guitar power chord riffs.[148] Pink Floyd released two of their heaviest and loudest songs to date; "Ibiza Bar" and "The Nile Song", which was regarded as "one of the heaviest songs the band recorded".[149][150] King Crimson's debut album started with "21st Century Schizoid Man", which was considered heavy metal by several critics.[151][152]

In January 1969, Led Zeppelin's self-titled debut album was released and reached number 10 on the Billboard album chart. In July, Zeppelin and a power trio with a Cream-inspired, but cruder sound, Grand Funk Railroad, played the Atlanta Pop Festival. That same month, another Cream-rooted trio led by Leslie West released Mountain, an album filled with heavy blues rock guitar and roaring vocals. In August, the group—now itself dubbed Mountain—played an hour-long set at the Woodstock Festival, exposing the crowd of 300,000 people to the emerging sound of heavy metal.[153][154] Mountain's proto-metal or early heavy metal hit song "Mississippi Queen" from the album Climbing! is especially credited with paving the way for heavy metal and was one of the first heavy guitar songs to receive regular play on radio.[153][155][156] In September 1969, the Beatles released the album Abbey Road containing the track "I Want You (She's So Heavy)" which has been credited as an early example of or influence on heavy metal or doom metal.[157][158] In October 1969, British band High Tide debuted with the heavy, proto-metal album Sea Shanties.[159][144]

Led Zeppelin defined central aspects of the emerging genre, with Page's highly distorted guitar style and singer Robert Plant's dramatic, wailing vocals.[160] Other bands, with a more consistently heavy, "purely" metal sound, would prove equally important in codifying the genre. The 1970 releases by Black Sabbath (Black Sabbath – generally accepted as the first heavy metal album[161] – and Paranoid) and Deep Purple (Deep Purple in Rock) were crucial in this regard.[119]

Birmingham's Black Sabbath had developed a particularly heavy sound in part due to an industrial accident guitarist Tony Iommi suffered before cofounding the band. Unable to play normally, Iommi had to tune his guitar down for easier fretting and rely on power chords with their relatively simple fingering.[162] The bleak, industrial, working class environment of Birmingham, a manufacturing city full of noisy factories and metalworking, has itself been credited with influencing Black Sabbath's heavy, chugging, metallic sound and the sound of heavy metal in general.[163][164][165][166]

Deep Purple had fluctuated between styles in its early years, but by 1969 vocalist Ian Gillan and guitarist Ritchie Blackmore had led the band toward the developing heavy metal style.[134] In 1970, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple scored major UK chart hits with "Paranoid" and "Black Night", respectively.[167][168] That same year, two other British bands released debut albums in a heavy metal mode: Uriah Heep with ... Very 'Eavy ... Very 'Umble and UFO with UFO 1. Bloodrock released their self-titled debut album, a collection of heavy guitar riffs, gruff style vocals and sadistic and macabre lyrics.[169] The influential Budgie brought the new metal sound into a power trio context, creating some of the heaviest music of the time.[170] The occult lyrics and imagery employed by Black Sabbath and Uriah Heep would prove particularly influential; Led Zeppelin also began foregrounding such elements with its fourth album, released in 1971.[171] In 1973, Deep Purple released the song "Smoke on the Water", with the iconic riff that is usually considered as the most recognizable one in "heavy rock" history, as a single of the classic live album Made in Japan.[172][173]

On the other side of the Atlantic, the trend-setting group was Grand Funk Railroad, described as "the most commercially successful American heavy-metal band from 1970 until they disbanded in 1976, [they] established the Seventies success formula: continuous touring".[174] Other influential bands identified with metal emerged in the U.S., such as Sir Lord Baltimore (Kingdom Come, 1970), Blue Öyster Cult (Blue Öyster Cult, 1972), Aerosmith (Aerosmith, 1973) and Kiss (Kiss, 1974). Sir Lord Baltimore's 1970 debut album and both Humble Pie's debut and self-titled third album were among the first albums to be described in print as "heavy metal", with As Safe As Yesterday Is referred to by the term "heavy metal" in a 1970 review in Rolling Stone magazine.[175][176][101][100] Various smaller bands from the U.S., U.K., and Continental Europe, including Bang, Josefus, Leaf Hound, Primeval, Hard Stuff, Truth and Janey, Dust, JPT Scare Band, Frijid Pink, Cactus, May Blitz, Captain Beyond, Toad, Granicus, Iron Claw, and Yesterday's Children, though lesser known outside of their respective scenes, proved to be greatly influential on the emerging metal movement. In Germany, Scorpions debuted with Lonesome Crow in 1972. Blackmore, who had emerged as a virtuoso soloist with Deep Purple's highly influential album Machine Head (1972), left the band in 1975 to form Rainbow with Ronnie James Dio, singer and bassist for blues rock band Elf and future vocalist for Black Sabbath and heavy metal band Dio. Rainbow with Ronnie James Dio would expand on the mystical and fantasy-based lyrics and themes sometimes found in heavy metal, pioneering both power metal and neoclassical metal.[177] These bands also built audiences via constant touring and increasingly elaborate stage shows.[119]

There are arguments about whether these and other early bands truly qualify as "heavy metal" or simply as "hard rock". Those closer to the music's blues roots or placing greater emphasis on melody are now commonly ascribed the latter label. AC/DC, which debuted with High Voltage in 1975, is a prime example. The 1983 Rolling Stone encyclopedia entry begins, "Australian heavy-metal band AC/DC".[178] Rock historian Clinton Walker writes, "Calling AC/DC a heavy metal band in the seventies was as inaccurate as it is today. ... [They] were a rock 'n' roll band that just happened to be heavy enough for metal".[179] The issue is not only one of shifting definitions, but also a persistent distinction between musical style and audience identification: Ian Christe describes how the band "became the stepping-stone that led huge numbers of hard rock fans into heavy metal perdition".[180]

In certain cases, there is little debate. After Black Sabbath, the next major example is Britain's Judas Priest, which debuted with Rocka Rolla in 1974. In Christe's description,

Black Sabbath's audience was ... left to scavenge for sounds with similar impact. By the mid-1970s, heavy metal aesthetic could be spotted, like a mythical beast, in the moody bass and complex dual guitars of Thin Lizzy, in the stagecraft of Alice Cooper, in the sizzling guitar and showy vocals of Queen, and in the thundering medieval questions of Rainbow. ... Judas Priest arrived to unify and amplify these diverse highlights from hard rock's sonic palette. For the first time, heavy metal became a true genre unto itself.[181]

Though Judas Priest did not have a top 40 album in the United States until 1980, for many it was the definitive post-Sabbath heavy metal band; its twin-guitar attack, featuring rapid tempos and a non-bluesy, more cleanly metallic sound, was a major influence on later acts.[5] While heavy metal was growing in popularity, most critics were not enamored of the music. Objections were raised to metal's adoption of visual spectacle and other trappings of commercial artifice,[182] but the main offense was its perceived musical and lyrical vacuity: reviewing a Black Sabbath album in the early 1970s, Robert Christgau described it as "dull and decadent ... dim-witted, amoral exploitation."[183]

Mainstream: late 1970s and 1980s

Punk rock emerged in the mid-1970s as a reaction against contemporary social conditions as well as what was perceived as the overindulgent, overproduced rock music of the time, including heavy metal. Sales of heavy metal records declined sharply in the late 1970s in the face of punk, disco, and more mainstream rock.[182] With the major labels fixated on punk, many newer British heavy metal bands were inspired by the movement's aggressive, high-energy sound and "lo-fi", do it yourself ethos. Underground metal bands began putting out cheaply recorded releases independently to small, devoted audiences.[184]

Motörhead, founded in 1975, was the first important band to straddle the punk/metal divide. With the explosion of punk in 1977, others followed. British music papers such as the NME and Sounds took notice, with Sounds writer Geoff Barton christening the movement the "New Wave of British Heavy Metal".[185] NWOBHM bands including Iron Maiden, Saxon, and Def Leppard re-energized the heavy metal genre. Following the lead set by Judas Priest and Motörhead, they toughened up the sound, reduced its blues elements, and emphasized increasingly fast tempos.[186]

"This seemed to be the resurgence of heavy metal," noted Ronnie James Dio, who joined Black Sabbath in 1979. "I've never thought there was a desurgence of heavy metal – if that's a word! – but it was important to me that, yet again [after Rainbow], I could be involved in something that was paving the way for those who are going to come after me."[187]

By 1980, the NWOBHM had broken into the mainstream, as albums by Iron Maiden and Saxon, as well as Motörhead, reached the British top 10. Though less commercially successful, NWOBHM bands such as Venom and Diamond Head would have a significant influence on metal's development.[188] In 1981, Motörhead became the first of this new breed of metal bands to top the UK charts with the live album No Sleep 'til Hammersmith.[189]

The first generation of metal bands was ceding the limelight. Deep Purple broke up soon after Blackmore's departure in 1975, and Led Zeppelin split following drummer John Bonham's death in 1980. Black Sabbath were plagued with infighting and substance abuse, while facing fierce competition from their opening band, Van Halen.[190][191] Eddie Van Halen established himself as one of the leading metal guitarists of the era. His solo on "Eruption", from the band's self-titled 1978 album, is considered a milestone.[192] Eddie Van Halen's sound even crossed over into pop music when his guitar solo was featured on the track "Beat It" by Michael Jackson (a U.S. number 1 in February 1983).[193]

Inspired by Van Halen's success, a metal scene began to develop in Southern California during the late 1970s. Based on the clubs of L.A.'s Sunset Strip, bands such as Mötley Crüe, Quiet Riot, Ratt, and W.A.S.P. were influenced by traditional heavy metal of the 1970s.[194] These acts incorporated the theatrics (and sometimes makeup) of glam metal or "hair metal" such as Alice Cooper and Kiss.[195] Glam metal bands were often visually distinguished by long, overworked hair styles accompanied by wardrobes which were sometimes considered cross-gender. The lyrics of these glam metal bands characteristically emphasized hedonism and wild behavior, including lyrics which involved sexual expletives and the use of narcotics.[196] In the wake of the new wave of British heavy metal and Judas Priest's breakthrough British Steel (1980), heavy metal became increasingly popular in the early 1980s. Many metal artists benefited from the exposure they received on MTV, which began airing in 1981—sales often soared if a band's videos screened on the channel.[197] Def Leppard's videos for Pyromania (1983) made them superstars in America and Quiet Riot became the first domestic heavy metal band to top the Billboard chart with Metal Health (1983). One of the seminal events in metal's growing popularity was the 1983 US Festival in California, where the "heavy metal day" featuring Ozzy Osbourne, Van Halen, Scorpions, Mötley Crüe, Judas Priest, and others drew the largest audiences of the three-day event.[198]

Between 1983 and 1984, heavy metal went from an 8 percent to a 20 percent share of all recordings sold in the U.S.[199] Several major professional magazines devoted to the genre were launched, including Kerrang! (in 1981) and Metal Hammer (in 1984), as well as a host of fan journals. In 1985, Billboard declared, "Metal has broadened its audience base. Metal music is no longer the exclusive domain of male teenagers. The metal audience has become older (college-aged), younger (pre-teen), and more female".[200]

By the mid-1980s, glam metal was a dominant presence on the U.S. charts, music television, and the arena concert circuit. New bands such as L.A.'s Warrant and acts from the East Coast like Poison and Cinderella became major draws, while Mötley Crüe and Ratt remained very popular. Bridging the stylistic gap between hard rock and glam metal, New Jersey's Bon Jovi became enormously successful with its third album, Slippery When Wet (1986). The similarly styled Swedish band Europe became international stars with The Final Countdown (1986). Its title track hit number 1 in 25 countries.[201] In 1987, MTV launched a show, Headbangers Ball, devoted exclusively to heavy metal videos. However, the metal audience had begun to factionalize, with those in many underground metal scenes favoring more extreme sounds and disparaging the popular style as "light metal" or "hair metal".[202]

One band that reached diverse audiences was Guns N' Roses. In contrast to their glam metal contemporaries in L.A., they were seen as much more raw and dangerous. With the release of their chart-topping Appetite for Destruction (1987), they "recharged and almost single-handedly sustained the Sunset Strip sleaze system for several years".[203] The following year, Jane's Addiction emerged from the same L.A. hard-rock club scene with its major label debut, Nothing's Shocking. Reviewing the album, Rolling Stone declared, "as much as any band in existence, Jane's Addiction is the true heir to Led Zeppelin".[204] The group was one of the first to be identified with the "alternative metal" trend that would come to the fore in the next decade. Meanwhile, new bands like New York City's Winger and New Jersey's Skid Row sustained the popularity of the glam metal style.[205]

Other heavy metal genres: 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s

_(5770925587).jpg.webp)

Many subgenres of heavy metal developed outside of the commercial mainstream during the 1980s[206] such as crossover thrash. Several attempts have been made to map the complex world of underground metal, most notably by the editors of AllMusic, as well as critic Garry Sharpe-Young. Sharpe-Young's multivolume metal encyclopedia separates the underground into five major categories: thrash metal, death metal, black metal, power metal, and the related subgenres of doom and gothic metal.[207]

In 1990, a review in Rolling Stone suggested retiring the term "heavy metal" as the genre was "ridiculously vague".[208] The article stated that the term only fueled "misperceptions of rock & roll bigots who still assume that five bands as different as Ratt, Extreme, Anthrax, Danzig and Mother Love Bone" sound the same.[208]

Thrash metal

Thrash metal emerged in the early 1980s under the influence of hardcore punk and the new wave of British heavy metal,[209] particularly songs in the revved-up style known as speed metal. The movement began in the United States, with Bay Area thrash metal being the leading scene. The sound developed by thrash groups was faster and more aggressive than that of the original metal bands and their glam metal successors.[209] Low-register guitar riffs are typically overlaid with shredding leads. Lyrics often express nihilistic views or deal with social issues using visceral, gory language. Thrash has been described as a form of "urban blight music" and "a palefaced cousin of rap".[210]

The subgenre was popularized by the "Big Four of Thrash": Metallica, Anthrax, Megadeth, and Slayer.[211] Three German bands, Kreator, Sodom, and Destruction, played a central role in bringing the style to Europe. Others, including San Francisco Bay Area's Testament and Exodus, New Jersey's Overkill, and Brazil's Sepultura and Sarcófago, also had a significant impact. Although thrash began as an underground movement, and remained largely that for almost a decade, the leading bands of the scene began to reach a wider audience. Metallica brought the sound into the top 40 of the Billboard album chart in 1986 with Master of Puppets, the genre's first platinum record.[212] Two years later, the band's ... And Justice for All hit number 6, while Megadeth and Anthrax also had top 40 records on the American charts.[213]

Though less commercially successful than the rest of the Big Four, Slayer released one of the genre's definitive records: Reign in Blood (1986) was credited for incorporating heavier guitar timbres, and for including explicit depictions of death, suffering, violence and occult into thrash metal's lyricism.[214] Slayer attracted a following among far-right skinheads, and accusations of promoting violence and Nazi themes have dogged the band.[215] Even though Slayer did not receive substantial media exposure, their music played a key role in the development of extreme metal.[216]

In the early 1990s, thrash achieved breakout success, challenging and redefining the metal mainstream.[217] Metallica's self-titled 1991 album topped the Billboard chart,[218] as the band established international following.[219] Megadeth's Countdown to Extinction (1992) debuted at number two,[220] Anthrax and Slayer cracked the top 10,[221] and albums by regional bands such as Testament and Sepultura entered the top 100.[222]

Death metal

Thrash soon began to evolve and split into more extreme metal genres. "Slayer's music was directly responsible for the rise of death metal," according to MTV News.[224] The NWOBHM band Venom was also an important progenitor. The death metal movement in both North America and Europe adopted and emphasized the elements of blasphemy and diabolism employed by such acts. Florida's Death, San Francisco Bay Area's Possessed, and Ohio's Necrophagia[225] are recognized as seminal bands in the style. All three have been credited with inspiring the subgenre's name. Possessed in particular did so via their 1984 demo Death Metal and their song "Death Metal", which came from their 1985 debut album Seven Churches (1985). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Swedish death metal became notable and melodic forms of death metal were created.[226]

Death metal utilizes the speed and aggression of both thrash and hardcore, fused with lyrics preoccupied with Z-grade slasher movie violence and Satanism.[227] Death metal vocals are typically bleak, involving guttural "death growls", high-pitched screaming, the "death rasp",[228] and other uncommon techniques.[229] Complementing the deep, aggressive vocal style are downtuned, heavily distorted guitars[227][228] and extremely fast percussion, often with rapid double bass drumming and "wall of sound"–style blast beats. Frequent tempo and time signature changes and syncopation are also typical.[230]

Death metal, like thrash metal, generally rejects the theatrics of earlier metal styles, opting instead for an everyday look of ripped jeans and plain leather jackets.[231] One major exception to this rule was Deicide's Glen Benton, who branded an inverted cross on his forehead and wore armor on stage. Morbid Angel adopted neo-fascist imagery.[231] These two bands, along with Death and Obituary, were leaders of the major death metal scene that emerged in Florida in the mid-1980s. In the UK, the related style of grindcore, led by bands such as Napalm Death and Extreme Noise Terror, emerged from the anarcho-punk movement.[227]

Black metal

The first wave of black metal emerged in Europe in the early and mid-1980s, led by the United Kingdom's Venom, Denmark's Mercyful Fate, Switzerland's Hellhammer and Celtic Frost, and Sweden's Bathory. By the late 1980s, Norwegian bands such as Mayhem and Burzum were heading a second wave.[232] Black metal varies considerably in style and production quality, although most bands emphasize shrieked and growled vocals, highly distorted guitars frequently played with rapid tremolo picking, a dark atmosphere[229] and intentionally lo-fi production, often with ambient noise and background hiss.[233]

Satanic themes are common in black metal, though many bands take inspiration from ancient paganism, promoting a return to supposed pre-Christian values.[234] Numerous black metal bands also "experiment with sounds from all possible forms of metal, folk, classical music, electronica and avant-garde".[228] Darkthrone drummer Fenriz explains, "It had something to do with production, lyrics, the way they dressed and a commitment to making ugly, raw, grim stuff. There wasn't a generic sound."[235]

Although bands such as Sarcófago had been donning corpsepaint, by 1990, Mayhem was regularly wearing corpsepaint; many other black metal acts also adopted the look. Bathory inspired the Viking metal and folk metal movements and Immortal brought blast beats to the fore. Some bands in the Scandinavian black metal scene became associated with considerable violence in the early 1990s,[236] with Mayhem and Burzum linked to church burnings. Growing commercial hype around death metal generated a backlash; beginning in Norway, much of the Scandinavian metal underground shifted to support a black metal scene that resisted being co-opted by the commercial metal industry.[237]

By 1992, black metal scenes had begun to emerge in areas outside Scandinavia, including Germany, France, and Poland.[238] The 1993 murder of Mayhem's Euronymous by Burzum's Varg Vikernes provoked intensive media coverage.[235] Around 1996, when many in the scene felt the genre was stagnating,[239] several key bands, including Burzum and Finland's Beherit, moved toward an ambient style, while symphonic black metal was explored by Sweden's Tiamat and Switzerland's Samael.[240] In the late 1990s and early 2000s decade, Norway's Dimmu Borgir brought black metal closer to the mainstream,[241] as did Cradle of Filth.[242]

Power metal

During the late 1980s, the power metal scene came together largely in reaction to the harshness of death and black metal.[243] Though a relatively underground style in North America, it enjoys wide popularity in Europe, Japan, and South America. Power metal focuses on upbeat, epic melodies and themes that "appeal to the listener's sense of valor and loveliness".[244] The prototype for the sound was established in the mid-to-late 1980s by Germany's Helloween, which in their 1987 and 1988 Keeper of the Seven Keys albums combined the power riffs, melodic approach, and high-pitched, "clean" singing style of bands like Judas Priest and Iron Maiden with thrash's speed and energy, "crystalliz[ing] the sonic ingredients of what is now known as power metal".[245]

Traditional power metal bands like Sweden's HammerFall, England's DragonForce, and America's Iced Earth have a sound clearly indebted to the classic NWOBHM style.[246] Many power metal bands such as America's Kamelot, Finnish groups Nightwish, Stratovarius and Sonata Arctica, Italy's Rhapsody of Fire, and Russia's Catharsis feature a keyboard-based "symphonic" sound, sometimes employing orchestras and opera singers. Power metal has built a strong fanbase in Japan and South America, where bands like Brazil's Angra and Argentina's Rata Blanca are popular.[247]

Closely related to power metal is progressive metal, which adopts the complex compositional approach of bands like Rush and King Crimson. This style emerged in the United States in the early and mid-1980s, with innovators such as Queensrÿche, Fates Warning, and Dream Theater. The mix of the progressive and power metal sounds is typified by New Jersey's Symphony X, whose guitarist Michael Romeo is among the most recognized of latter-day shredders.[248]

Doom metal

Emerging in the mid-1980s with such bands as California's Saint Vitus, Maryland's The Obsessed, Chicago's Trouble, and Sweden's Candlemass, the doom metal movement rejected other metal styles' emphasis on speed, slowing its music to a crawl. Doom metal traces its roots to the lyrical themes and musical approach of early Black Sabbath.[249] The Melvins have also been a significant influence on doom metal and a number of its subgenres.[250] Doom emphasizes melody, melancholy tempos, and a sepulchral mood relative to many other varieties of metal.[251]

The 1991 release of Forest of Equilibrium, the debut album by UK band Cathedral, helped spark a new wave of doom metal. During the same period, the doom-death fusion style of British bands Paradise Lost, My Dying Bride, and Anathema gave rise to European gothic metal.[252] with its signature dual-vocalist arrangements, exemplified by Norway's Theatre of Tragedy and Tristania. New York's Type O Negative introduced an American take on the style.[253]

In the United States, sludge metal, mixing doom and hardcore, emerged in the late 1980s—Eyehategod and Crowbar were leaders in a major Louisiana sludge scene. Early in the next decade, California's Kyuss and Sleep, inspired by the earlier doom metal bands, spearheaded the rise of stoner metal,[254] while Seattle's Earth helped develop the drone metal subgenre.[255] The late 1990s saw new bands form such as the Los Angeles–based Goatsnake, with a classic stoner/doom sound, and Sunn O))), which crosses lines between doom, drone, and dark ambient metal—the New York Times has compared their sound to an "Indian raga in the middle of an earthquake".[251]

1990s and early 2000s subgenres and fusions

The era of heavy metal's mainstream dominance in North America came to an end in the early 1990s with the emergence of Nirvana and other grunge bands, signaling the popular breakthrough of alternative rock.[256] Grunge acts were influenced by the heavy metal sound, but rejected the excesses of the more popular metal bands, such as their "flashy and virtuosic solos" and "appearance-driven" MTV orientation.[205]

Glam metal fell out of favor due not only to the success of grunge,[257] but also because of the growing popularity of the more aggressive sound typified by Metallica and the post-thrash groove metal of Pantera and White Zombie.[258] In 1991, the band Metallica released their album Metallica, also known as The Black Album, which moved the band's sound out of the thrash metal genre and into standard heavy metal.[259] The album was certified 16× Platinum by the RIAA.[260] A few new, unambiguously metal bands had commercial success during the first half of the decade—Pantera's Far Beyond Driven topped the Billboard chart in 1994—but, "In the dull eyes of the mainstream, metal was dead".[261] Some bands tried to adapt to the new musical landscape. Metallica revamped its image: the band members cut their hair and, in 1996, headlined the alternative musical festival Lollapalooza founded by Jane's Addiction singer Perry Farrell. While this prompted a backlash among some long-time fans,[262] Metallica remained one of the most successful bands in the world into the new century.[263]

Like Jane's Addiction, many of the most popular early 1990s groups with roots in heavy metal fall under the umbrella term "alternative metal".[264] Bands in Seattle's grunge scene such as Soundgarden, credited as making a "place for heavy metal in alternative rock",[265] and Alice in Chains were at the center of the alternative metal movement. The label was applied to a wide spectrum of other acts that fused metal with different styles: Faith No More combined their alternative rock sound with punk, funk, metal, and hip hop; Primus joined elements of funk, punk, thrash metal, and experimental music; Tool mixed metal and progressive rock; bands such as Fear Factory, Ministry and Nine Inch Nails began incorporating metal into their industrial sound, and vice versa, respectively; and Marilyn Manson went down a similar route, while also employing shock effects of the sort popularized by Alice Cooper. Alternative metal artists, though they did not represent a cohesive scene, were united by their willingness to experiment with the metal genre and their rejection of glam metal aesthetics (with the stagecraft of Marilyn Manson and White Zombie—also identified with alt-metal—significant, if partial, exceptions).[264] Alternative metal's mix of styles and sounds represented "the colorful results of metal opening up to face the outside world."[266]

In the mid- and late 1990s came a new wave of U.S. metal groups inspired by the alternative metal bands and their mix of genres.[267] Dubbed "nu metal", bands such as Slipknot, Linkin Park, Limp Bizkit, Papa Roach, P.O.D., Korn and Disturbed incorporated elements ranging from death metal to hip hop, often including DJs and rap-style vocals. The mix demonstrated that "pancultural metal could pay off".[268] Nu metal gained mainstream success through heavy MTV rotation and Ozzy Osbourne's 1996 introduction of Ozzfest, which led the media to talk of a resurgence of heavy metal.[269] In 1999, Billboard noted that there were more than 500 specialty metal radio shows in the United States, nearly three times as many as ten years before.[270] While nu metal was widely popular, traditional metal fans did not fully embrace the style.[271] By early 2003, the movement's popularity was on the wane, though several nu metal acts such as Korn or Limp Bizkit retained substantial followings.[272]

Recent styles: mid–late 2000s, 2010s and 2020s

Metalcore, a hybrid of extreme metal and hardcore punk,[273] emerged as a commercial force in the mid-2000s decade. Through the 1980s and 1990s, metalcore was mostly an underground phenomenon;[274] pioneering bands include Earth Crisis,[275][276] other prominent bands include Converge,[275] Hatebreed[276][277] and Shai Hulud.[278][279] By 2004, melodic metalcore—influenced as well by melodic death metal—was popular enough that Killswitch Engage's The End of Heartache and Shadows Fall's The War Within debuted at numbers 21 and 20, respectively, on the Billboard album chart.[280]

Evolving even further from metalcore comes mathcore, a more rhythmically complicated and progressive style brought to light by bands such as The Dillinger Escape Plan, Converge, and Protest the Hero.[281] Mathcore's main defining quality is the use of odd time signatures, and has been described to possess rhythmic comparability to free jazz.[282]

Heavy metal remained popular in the 2000s, particularly in continental Europe. By the new millennium Scandinavia had emerged as one of the areas producing innovative and successful bands, while Belgium, The Netherlands and especially Germany were the most significant markets.[283] Metal music is more favorably embraced in Scandinavia and Northern Europe than other regions due to social and political openness in these regions;[284] especially Finland has been often called the "Promised Land of Heavy Metal", because nowadays there are more than 50 metal Bands for every 100,000 inhabitants – more than any other nation in the world.[285][286] Established continental metal bands that placed multiple albums in the top 20 of the German charts between 2003 and 2008, including Finnish band Children of Bodom,[287] Norwegian act Dimmu Borgir,[288] Germany's Blind Guardian[289] and Sweden's HammerFall.[290]

In the 2000s, an extreme metal fusion genre known as deathcore emerged. Deathcore incorporates elements of death metal, hardcore punk and metalcore.[291][292] Deathcore features characteristics such as death metal riffs, hardcore punk breakdowns, death growling, "pig squeal"-sounding vocals, and screaming.[293][294] Deathcore bands include Whitechapel, Suicide Silence, Despised Icon and Carnifex.[295]

The term "retro-metal" has been used to describe bands such as Texas-based The Sword, California's High on Fire, Sweden's Witchcraft,[296] and Australia's Wolfmother.[296][297] The Sword's Age of Winters (2006) drew heavily on the work of Black Sabbath and Pentagram,[298] Witchcraft added elements of folk rock and psychedelic rock,[299] and Wolfmother's self-titled 2005 debut album had "Deep Purple-ish organs" and "Jimmy Page-worthy chordal riffing". Mastodon, which plays in a progressive/sludge style, has inspired claims of a metal revival in the United States, dubbed by some critics the "New Wave of American Heavy Metal".[300]

By the early 2010s, metalcore was evolving to more frequently incorporate synthesizers and elements from genres beyond rock and metal. The album Reckless & Relentless by British band Asking Alexandria (which sold 31,000 copies in its first week), and The Devil Wears Prada's 2011 album Dead Throne (which sold 32,400 in its first week)[301] reached up to number 9 and 10,[302] respectively, on the Billboard 200 chart. In 2013, British band Bring Me the Horizon released their fourth studio album Sempiternal to critical acclaim. The album debuted at number 3 on the UK Album Chart and at number 1 in Australia. The album sold 27,522 copies in the US, and charted at number 11 on the US Billboard Chart, making it their highest charting release in America until their follow-up album That's the Spirit debuted at no. 2 in 2015.

Also in the 2010s, a metal style called "djent" developed as a spinoff of standard progressive metal.[303][304] Djent music uses rhythmic and technical complexity,[305] heavily distorted, palm-muted guitar chords, syncopated riffs[306] and polyrhythms alongside virtuoso soloing.[303] Another typical characteristic is the use of extended range seven, eight, and nine-string guitars.[307] Djent bands include Periphery, Tesseract[308] and Textures.[309]

Fusion of nu metal with electropop by singer-songwriters Poppy, Grimes and Rina Sawayama saw a popular and critical revival of the former genre in the late 2010s and 2020s, particular on their respective albums I Disagree, Miss Anthropocene and Sawayama.[310][311][312][313]

Women in heavy metal

Women's involvement in heavy metal began in the 1970s when Genesis, the forerunner of Vixen, formed in 1973. The hard rock band featuring all-female members, The Runaways, was founded in 1975; Joan Jett and Lita Ford later had successful solo careers.[314] In 1978, during the rise of the new wave of British heavy metal, the band Girlschool was founded, and in 1980 collaborated with Motörhead under the pseudonym Headgirl. Starting in 1984, Doro Pesch, dubbed "the Metal Queen", reached success across Europe leading the German band Warlock, before starting her solo career.

In 1994, Liv Kristine joined Norwegian gothic metal band Theatre of Tragedy, providing 'angelic'[315] female clean vocals to contrast with male death growls. In 1996, Finnish band Nightwish was founded, featuring Tarja Turunen's vocals. This was followed by more women fronting heavy metal bands, such as Halestorm, In This Moment, Within Temptation, Arch Enemy, and Epica among others. In Japan, the 2010s saw a boom of all-female metal bands including Destrose, Aldious, Mary's Blood, Cyntia, and Lovebites.[316][317]

Liv Kristine was featured on the title track of Cradle of Filth's 2004 album Nymphetamine which was nominated for the 2004 Grammy Award for Best Metal Performance.[318] In 2013, Halestorm won the Grammy in the combined category of Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance for "Love Bites (So Do I)".[319] In 2021, In This Moment, Code Orange and Poppy were all nominated in the Best Metal Performance category.[320]

Women such as Gaby Hoffmann and Sharon Osbourne have held important managerial role behind the scenes. In 1981, Hoffmann helped Don Dokken acquire his first record deal.[321] Hoffmann also became the manager of Accept in 1981 and wrote songs under the pseudonym of "Deaffy" for many of band's studio albums. Vocalist Mark Tornillo stated that Hoffmann still had some influence in songwriting on their later albums.[322] Osbourne, the wife and manager of Ozzy Osbourne, founded the Ozzfest music festival and managed several bands, including Motörhead, Coal Chamber, The Smashing Pumpkins, Electric Light Orchestra, Lita Ford and Queen.[323]

Sexism

The popular media and academia have long charged heavy metal with sexism and misogyny. In the 1980s, American conservative groups like the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) and the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) coopted feminist views on anti-woman violence to form attacks on metal's rhetoric and imagery.[324] According to Robert Christgau in 2001, metal, along with hip hop, have made "reflexive and violent sexism ... current in the music".[325]

In response to such claims, debates in the metal press have centered on defining and contextualizing sexism. Hill claims that "understanding what counts as sexism is complex and requires critical work by fans when sexism is normalised." Citing her own research, including interviews of British female fans, she finds that metal offers them an opportunity to feel liberated and genderless, albeit if assimilated into a culture that is largely neglectful of women.[324]

In 2018, Metal Hammer editor Eleanor Goodman published an article titled "Does Metal Have a Sexism Problem?", interviewing veteran industry people and artists about the plight of women in metal. Some talked about a history of difficulty receiving professional respect from male counterparts. Among those interviewed was Wendy Dio, who had worked in label, booking, and legal capacities in the music industry before her marriage to and management of metal artist Ronnie James Dio. She said that after marrying Dio, her professional reputation became reduced to her marital role as his wife and her competency was questioned. Gloria Cavalera, former manager of Sepultura and wife of the band's former frontman Max Cavalera, said that since 1996 she had received misogynistic hate-mail and death threats from fans and that, "Women take a lot of crap. This whole #metoo thing, do they think it just started? That has gone on since the pictures of the cavemen pulling girls by their hair."[326]

Notes

- Pearlman goes on to say, "A mechanically hysterical audience is matched to a mechanically hysterical sound. Side two of the album is a metal side. Most mechanical ... the to-date definitive metal song: 'Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?,' as hysterical and tense as can be ... A sloppy performance—but never flaccid. Some bad detail, but lots of tension. It's a mechanical conception and realization (like all metal songs)—with the instruments and Mick's voice densely organized into hard, sharp-edged planes of sound: a construction of aural surfaces and regular surfaced planes, a planar conception, the product of a mechanistic discipline, with an emphasis upon the geometrical organization of percussive sounds."[96]

References

- "Grunge". AllMusic. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- Havers, Richard (29 March 2022). "Heavy Metal Thunder: The Origins of Heavy Metal". udiscovermusic. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- Tom Larson (2004). History of Rock and Roll. Kendall/Hunt Pub. pp. 183–187. ISBN 978-0-7872-9969-9.

- "Heavy Metal Music Genre Overview". Allmusic. Retrieved 9 January 2022

- Walser (1993), p. 6

- "As much as Sabbath started it, Priest were the ones who took it out of the blues and straight into metal." Bowe, Brian J. Judas Priest: Metal Gods. ISBN 0-7660-3621-9

- Fast (2005), pp. 89–91; Weinstein (2000), pp. 7, 8, 23, 36, 103, 104

- Pareles, Jon. "Heavy Metal, Weighty Words" The New York Times, 10 July 1988. Retrieved on 14 November 2007

- Weinstein (2000), p. 25

- Hannum, Terence (18 March 2016). "Instigate Sonic Violence: A Not-so-Brief History of the Synthesizer's Impact on Heavy Metal". noisey.vice.com. Vice. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

In almost every subgenre of heavy metal, synthesizers held sway. Look at Cynic, who on their progressive death metal opus Focus (1993) had keyboards appear on the album and during live performances, or British gothic doom band My Dying Bride, who relied heavily on synths for their 1993 album, Turn Loose the Swans. American noise band Today is the Day used synthesizers on their 1996 self titled album to powerfully add to their din. Voivod even put synthesizers to use for the first time on 1991's Angel Rat and 1993's The Outer Limits, played by both guitarist Piggy and drummer Away. The 1990s were a gold era for the use of synthesizers in heavy metal, and only paved the way for the further explorations of the new millennia.

- Weinstein (2000), p. 23

- Walser, Robert (1993). Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Wesleyan University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-8195-6260-2

- Hodgson, Peter (9 April 2011). "METAL 101: Face-melting guitar tones". I Heart Guitar. Archived from the original on 13 April 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Weinstein, p. 24

- Walser, p. 50

- Dickinson, Kay (2003). Movie Music, the Film Reader. Psychology Press. p. 158.

- Grow, Kory (26 February 2010). "Final Six: The Six Best/Worst Things to Come out of Nu-Metal". Revolver magazine. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

The death of the guitar solo[:] In its efforts to tune down and simplify riffs, nu-metal effectively drove a stake through the heart of the guitar solo

- "Lesson four- Power chords". Marshall Amps

- Damage Incorporated: Metallica and the Production of Musical Identity. By Glenn Pillsbury. Routledge, 2013

- Weinstein (2000), p. 26

- Cited in Weinstein (2000), p. 26

- Weinstein (2000), p. 24

- Weinstein (2009), p. 24