Oxytocin

Oxytocin (Oxt or OT) is a peptide hormone and neuropeptide normally produced in the hypothalamus and released by the posterior pituitary.[3] It plays a role in social bonding, reproduction, childbirth, and the period after childbirth.[4][5][6][7] Oxytocin is released into the bloodstream as a hormone in response to sexual activity and during labour.[8][9] It is also available in pharmaceutical form. In either form, oxytocin stimulates uterine contractions to speed up the process of childbirth. In its natural form, it also plays a role in bonding with the baby and milk production.[9][10] Production and secretion of oxytocin is controlled by a positive feedback mechanism, where its initial release stimulates production and release of further oxytocin. For example, when oxytocin is released during a contraction of the uterus at the start of childbirth, this stimulates production and release of more oxytocin and an increase in the intensity and frequency of contractions. This process compounds in intensity and frequency and continues until the triggering activity ceases. A similar process takes place during lactation and during sexual activity.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɒksɪˈtoʊsɪn/ |

| Physiological data | |

| Source tissues | pituitary gland |

| Target tissues | wide spread |

| Receptors | oxytocin receptor |

| Antagonists | atosiban |

| Precursor | oxytocin/neurophysin I prepropeptide |

| Metabolism | liver and other oxytocinases |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 30% |

| Metabolism | liver and other oxytocinases |

| Elimination half-life | 1–6 min (IV) ~2 h (intranasal)[1][2] |

| Excretion | Biliary and kidney |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.045 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C43H66N12O12S2 |

| Molar mass | 1007.19 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

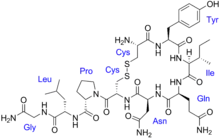

Oxytocin is derived by enzymatic splitting from the peptide precursor encoded by the human OXT gene. The deduced structure of the active nonapeptide is:

Etymology

The term "oxytocin" derives from the Greek "ὠκυτόκος" (ōkutókos), based on ὀξύς (oxús), meaning "sharp" or "swift", and τόκος (tókos), meaning "childbirth".[11][12] The adjective form is "oxytocic", which refers to medicines which stimulate uterine contractions, to speed up the process of childbirth.

History

The uterine-contracting properties of the principle that would later be named oxytocin were discovered by British pharmacologist Henry Hallett Dale in 1906,[13][14] and its milk ejection property was described by Ott and Scott in 1910[15] and by Schafer and Mackenzie in 1911.[16]

In the 1920s, oxytocin and vasopressin were isolated from pituitary tissue and given their current names.

Oxytocin's molecular structure was determined in 1952.[17] In the early 1950s, American biochemist Vincent du Vigneaud found that oxytocin is made up of nine amino acids, and he identified its amino acid sequence, the first polypeptide hormone to be sequenced.[18] In 1953, du Vigneaud carried out the synthesis of oxytocin, the first polypeptide hormone to be synthesized.[19][20][21] Du Vigneaud was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1955 for his work.[22]

Further work on different synthetic routes for oxytocin, as well as the preparation of analogues of the hormone (e.g. 4-deamido-oxytocin) was performed in the following decade by Iphigenia Photaki.[23]

Biochemistry

Estrogen has been found to increase the secretion of oxytocin and to increase the expression of its receptor, the oxytocin receptor, in the brain.[28] In women, a single dose of estradiol has been found to be sufficient to increase circulating oxytocin concentrations.[29]

Biosynthesis

Oxytocin and vasopressin are the only known hormones released by the human posterior pituitary gland to act at a distance. However, oxytocin neurons make other peptides, including corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and dynorphin, for example, that act locally. The magnocellular neurons that make oxytocin are adjacent to magnocellular neurons that make vasopressin, and are similar in many respects.

The oxytocin peptide is synthesized as an inactive precursor protein from the OXT gene.[30][31][32] This precursor protein also includes the oxytocin carrier protein neurophysin I.[33] The inactive precursor protein is progressively hydrolyzed into smaller fragments (one of which is neurophysin I) via a series of enzymes. The last hydrolysis that releases the active oxytocin nonapeptide is catalyzed by peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase (PAM).[34]

The activity of the PAM enzyme system is dependent upon vitamin C (ascorbate), which is a necessary vitamin cofactor. By chance, sodium ascorbate by itself was found to stimulate the production of oxytocin from ovarian tissue over a range of concentrations in a dose-dependent manner.[35] Many of the same tissues (e.g. ovaries, testes, eyes, adrenals, placenta, thymus, pancreas) where PAM (and oxytocin by default) is found are also known to store higher concentrations of vitamin C.[36]

Oxytocin is known to be metabolized by the oxytocinase, leucyl/cystinyl aminopeptidase.[37][38] Other oxytocinases are also known to exist.[37][39] Amastatin, bestatin (ubenimex), leupeptin, and puromycin have been found to inhibit the enzymatic degradation of oxytocin, though they also inhibit the degradation of various other peptides, such as vasopressin, met-enkephalin, and dynorphin A.[39][40][41][42]

Neural sources

In the hypothalamus, oxytocin is made in magnocellular neurosecretory cells of the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei,[43] and is stored in Herring bodies at the axon terminals in the posterior pituitary. It is then released into the blood from the posterior lobe (neurohypophysis) of the pituitary gland. These axons (likely, but dendrites have not been ruled out) have collaterals that innervate neurons in the nucleus accumbens, a brain structure where oxytocin receptors are expressed.[44] The endocrine effects of hormonal oxytocin and the cognitive or behavioral effects of oxytocin neuropeptides are thought to be coordinated through its common release through these collaterals.[44] Oxytocin is also produced by some neurons in the paraventricular nucleus that project to other parts of the brain and to the spinal cord.[45] Depending on the species, oxytocin receptor-expressing cells are located in other areas, including the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis.

In the pituitary gland, oxytocin is packaged in large, dense-core vesicles, where it is bound to neurophysin I as shown in the inset of the figure; neurophysin is a large peptide fragment of the larger precursor protein molecule from which oxytocin is derived by enzymatic cleavage.

Secretion of oxytocin from the neurosecretory nerve endings is regulated by the electrical activity of the oxytocin cells in the hypothalamus. These cells generate action potentials that propagate down axons to the nerve endings in the pituitary; the endings contain large numbers of oxytocin-containing vesicles, which are released by exocytosis when the nerve terminals are depolarised.

Non-neural sources

Endogenous oxytocin concentrations in the brain have been found to be as much as 1000-fold higher than peripheral levels.[46]

Outside the brain, oxytocin-containing cells have been identified in several diverse tissues, including in females in the corpus luteum[47][48] and the placenta;[49] in males in the testicles' interstitial cells of Leydig;[50] and in both sexes in the retina,[51] the adrenal medulla,[52] the thymus[53] and the pancreas.[54] The finding of significant amounts of this classically "neurohypophysial" hormone outside the central nervous system raises many questions regarding its possible importance in these diverse tissues.

Male

The Leydig cells in some species have been shown to possess the biosynthetic machinery to manufacture testicular oxytocin de novo, to be specific, in rats (which can synthesize vitamin C endogenously), and in guinea pigs, which, like humans, require an exogenous source of vitamin C (ascorbate) in their diets.[55]

Female

Oxytocin is synthesized by corpora lutea of several species, including ruminants and primates. Along with estrogen, it is involved in inducing the endometrial synthesis of prostaglandin F2α to cause regression of the corpus luteum.[56]

Evolution

Virtually all vertebrates have an oxytocin-like nonapeptide hormone that supports reproductive functions and a vasopressin-like nonapeptide hormone involved in water regulation. The two genes are usually located close to each other (less than 15,000 bases apart) on the same chromosome, and are transcribed in opposite directions (however, in fugu,[57] the homologs are further apart and transcribed in the same direction).

The two genes are believed to result from a gene duplication event; the ancestral gene is estimated to be about 500 million years old and is found in cyclostomata (modern members of the Agnatha).[58]

Biological function

Oxytocin has peripheral (hormonal) actions, and also has actions in the brain. Its actions are mediated by specific oxytocin receptors. The oxytocin receptor is a G-protein-coupled receptor, OT-R, which requires magnesium and cholesterol and is expressed in myometrial cells.[59] It belongs to the rhodopsin-type (class I) group of G-protein-coupled receptors.[58]

Studies have looked at oxytocin's role in various behaviors, including orgasm, social recognition, pair bonding, anxiety, in-group bias, situational lack of honesty, autism, and maternal behaviors.[14] Oxytocin is believed to have a significant role in social learning. There are indicators that oxytocin may help to decrease noise in the brain's auditory system, increase perception of social cues and support more targeted social behavior. It may also enhance reward responses. However, its effects may be influenced by context, such as the presence of familiar or unfamiliar individuals.[60][61]

Physiological

The peripheral actions of oxytocin mainly reflect secretion from the pituitary gland. The behavioral effects of oxytocin are thought to reflect release from centrally projecting oxytocin neurons, different from those that project to the pituitary gland, or that are collaterals from them.[44] Oxytocin receptors are expressed by neurons in many parts of the brain and spinal cord, including the amygdala, ventromedial hypothalamus, septum, nucleus accumbens, and brainstem, although the distribution differs markedly between species.[58] Furthermore, the distribution of these receptors changes during development and has been observed to change after parturition in the montane vole.[58]

- Milk ejection reflex/Letdown reflex: in lactating (breastfeeding) mothers, oxytocin acts at the mammary glands, causing milk to be 'let down' into lactiferous ducts, from where it can be excreted via the nipple.[62] Suckling by the infant at the nipple is relayed by spinal nerves to the hypothalamus. The stimulation causes neurons that make oxytocin to fire action potentials in intermittent bursts; these bursts result in the secretion of pulses of oxytocin from the neurosecretory nerve terminals of the pituitary gland.

- Uterine contraction: important for cervical dilation before birth, oxytocin causes contractions during the second and third stages of labor.[63] Oxytocin release during breastfeeding causes mild but often painful contractions during the first few weeks of lactation. This also serves to assist the uterus in clotting the placental attachment point postpartum. However, in knockout mice lacking the oxytocin receptor, reproductive behavior and parturition are normal.[64]

- In male rats, oxytocin may induce erections.[65] A burst of oxytocin is released during ejaculation in several species, including human males; its suggested function is to stimulate contractions of the reproductive tract, aiding sperm release.[65]

- Human sexual response: Oxytocin levels in plasma rise during sexual stimulation and orgasm. At least two uncontrolled studies have found increases in plasma oxytocin at orgasm – in both men and women.[66][67] Plasma oxytocin levels are increased around the time of self-stimulated orgasm and are still higher than baseline when measured five minutes after self arousal.[66] The authors of one of these studies speculated that oxytocin's effects on muscle contractibility may facilitate sperm and egg transport.[66]

- In a study measuring oxytocin serum levels in women before and after sexual stimulation, the author suggests it serves an important role in sexual arousal. This study found genital tract stimulation resulted in increased oxytocin immediately after orgasm.[68] Another study reported increases of oxytocin during sexual arousal could be in response to nipple/areola, genital, and/or genital tract stimulation as confirmed in other mammals.[69] Murphy et al. (1987), studying men, found that plasma oxytocin levels remain unchanged during sexual arousal, but that levels increase sharply after ejaculation, returning to baseline levels within 30 minutes. In contrast, vasopressin was increased during arousal but returned to baseline at the time of ejaculation. The study concludes that (in males) vasopressin is secreted during arousal, while oxytocin is only secreted after ejaculation.[70] A more recent study of men found an increase in plasma oxytocin immediately after orgasm, but only in a portion of their sample that did not reach statistical significance. The authors noted these changes "may simply reflect contractile properties on reproductive tissue".[71]

- Due to its similarity to vasopressin, it can reduce the excretion of urine slightly, and so it can be classified as an antidiuretic. In several species, oxytocin can stimulate sodium excretion from the kidneys (natriuresis), and, in humans, high doses can result in low sodium levels (hyponatremia).

- Cardiac effects: oxytocin and oxytocin receptors are also found in the heart in some rodents, and the hormone may play a role in the embryonal development of the heart by promoting cardiomyocyte differentiation.[72][73] However, the absence of either oxytocin or its receptor in knockout mice has not been reported to produce cardiac insufficiencies.[64]

- Modulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: oxytocin, under certain circumstances, indirectly inhibits release of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol and, in those situations, may be considered an antagonist of vasopressin.[74]

- Preparing fetal neurons for delivery (in rats): crossing the placenta, maternal oxytocin reaches the fetal brain and induces a switch in the action of neurotransmitter GABA from excitatory to inhibitory on fetal cortical neurons. This silences the fetal brain for the period of delivery and reduces its vulnerability to hypoxic damage.[75]

- Feeding: a 2012 paper suggested that oxytocin neurons in the para-ventricular hypothalamus in the brain may play a key role in suppressing appetite under normal conditions and that other hypothalamic neurons may trigger eating via inhibition of these oxytocin neurons. This population of oxytocin neurons is absent in Prader-Willi syndrome, a genetic disorder that leads to uncontrollable feeding and obesity, and may play a key role in its pathophysiology.[76] Research on the oxytocin-related neuropeptide asterotocin in starfish also showed that in echinoderms, the chemical induces muscle relaxation, and in starfish specifically caused the organisms to evert their stomach and react as though feeding on prey, even when none were present.[77]

Psychological

- Autism: Oxytocin has been implicated in the etiology of autism, with one report suggesting autism is correlated to a mutation on the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR). Studies involving Caucasian, Finnish and Chinese Han families provide support for the relationship of OXTR with autism.[78][79] Autism may also be associated with an aberrant methylation of OXTR.[78]

- Protection of brain functions: Studies in rats have demonstrated that nasal application of oxytocin can alleviate impaired learning capabilities caused by restrained stress. The authors attributed this effect to an improved hippocampal response in Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) being observed.[80] Accordingly, oxytocin has been shown to promote neural growth in the hippocampus in rats even during swim stress or glucocorticoid administration.[81] In a mouse model of early onset of Alzheimer's, the administration of oxytocin by a gel particularly designed to make the peptide accessible for the brain, the cognitive decline and hippocampal atrophy of these mice were delayed. Moreover, the amyloid β-protein deposit and nerve cell apoptosis were retarded. An observed inhibitory impact by oxytocin on the inflammatory activity of the microglia was proposed to be an important factor.[82]

Bonding

In the prairie vole, oxytocin released into the brain of the female during sexual activity is important for forming a pair bond with her sexual partner. Vasopressin appears to have a similar effect in males.[83] Oxytocin has a role in social behaviors in many species, so it likely also does in humans. In a 2003 study, both humans and dog oxytocin levels in the blood rose after a five to 24 minute petting session. This possibly plays a role in the emotional bonding between humans and dogs.[84]

- Maternal behavior: Female rats given oxytocin antagonists after giving birth do not exhibit typical maternal behavior.[85] By contrast, virgin female sheep show maternal behavior toward foreign lambs upon cerebrospinal fluid infusion of oxytocin, which they would not do otherwise.[86] Oxytocin is involved in the initiation of human maternal behavior, not its maintenance; for example, it is higher in mothers after they interact with unfamiliar children rather than their own.[87]

- Human ingroup bonding: Oxytocin can increase positive attitudes, such as bonding, toward individuals with similar characteristics, who then become classified as "in-group" members, whereas individuals who are dissimilar become classified as "out-group" members. Race can be used as an example of in-group and out-group tendencies because society often categorizes individuals into groups based on race (Caucasian, African American, Latino, etc.). One study that examined race and empathy found that participants receiving nasally administered oxytocin had stronger reactions to pictures of in-group members making pained faces than to pictures of out-group members with the same expression.[88] Moreover, individuals of one race may be more inclined to help individuals of the same race than individuals of another race when they are experiencing pain. Oxytocin has also been implicated in lying when lying would prove beneficial to other in-group members. In a study where such a relationship was examined, it was found that when individuals were administered oxytocin, rates of dishonesty in the participants' responses increased for their in-group members when a beneficial outcome for their group was expected.[89] Both of these examples show the tendency of individuals to act in ways that benefit those considered to be members of their social group, or in-group.

Oxytocin is not only correlated with the preferences of individuals to associate with members of their own group, but it is also evident during conflicts between members of different groups. During conflict, individuals receiving nasally administered oxytocin demonstrate more frequent defense-motivated responses toward in-group members than out-group members. Further, oxytocin was correlated with participant desire to protect vulnerable in-group members, despite that individual's attachment to the conflict.[90] Similarly, it has been demonstrated that when oxytocin is administered, individuals alter their subjective preferences in order to align with in-group ideals over out-group ideals.[91] These studies demonstrate that oxytocin is associated with intergroup dynamics. Further, oxytocin influences the responses of individuals in a particular group to those of another group. The in-group bias is evident in smaller groups; however, it can also be extended to groups as large as one's entire country leading toward a tendency of strong national zeal. A study done in the Netherlands showed that oxytocin increased the in-group favoritism of their nation while decreasing acceptance of members of other ethnicities and foreigners.[92] People also show more affection for their country's flag while remaining indifferent to other cultural objects when exposed to oxytocin.[93] It has thus been hypothesized that this hormone may be a factor in xenophobic tendencies secondary to this effect. Thus, oxytocin appears to affect individuals at an international level where the in-group becomes a specific "home" country and the out-group grows to include all other countries.

Drugs

- Drug interaction: According to several studies in animals, oxytocin inhibits the development of tolerance to various addictive drugs (opiates, cocaine, alcohol), and reduces withdrawal symptoms.[94] MDMA (ecstasy) may increase feelings of love, empathy, and connection to others by stimulating oxytocin activity primarily via activation of serotonin 5-HT1A receptors, if initial studies in animals apply to humans.[95] The anxiolytic drug buspirone may produce some of its effects via 5-HT1A receptor-induced oxytocin stimulation as well.[96][97]

- Addiction vulnerability: Concentrations of endogenous oxytocin can impact the effects of various drugs and one's susceptibility to substance use disorders, with higher concentrations associated with lower susceptibility. The status of the endogenous oxytocin system can enhance or reduce susceptibility to addiction through its bidirectional interaction with numerous systems, including the dopamine system, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the immune system. Individual differences in the endogenous oxytocin system based on genetic predisposition, gender and environmental influences, may therefore affect addiction vulnerability.[98] Oxytocin may be related to the place conditioning behaviors observed in habitual drug abusers.

Fear and anxiety

Oxytocin is typically remembered for the effect it has on prosocial behaviors, such as its role in facilitating trust and attachment between individuals.[99] However, oxytocin has a more complex role than solely enhancing prosocial behaviors. There is consensus that oxytocin modulates fear and anxiety; that is, it does not directly elicit fear or anxiety.[100] Two dominant theories explain the role of oxytocin in fear and anxiety. One theory states that oxytocin increases approach/avoidance to certain social stimuli and the second theory states that oxytocin increases the salience of certain social stimuli, causing the animal or human to pay closer attention to socially relevant stimuli.[101]

Nasally administered oxytocin has been reported to reduce fear, possibly by inhibiting the amygdala (which is thought to be responsible for fear responses).[102] Indeed, studies in rodents have shown oxytocin can efficiently inhibit fear responses by activating an inhibitory circuit within the amygdala.[103][104] Some researchers have argued oxytocin has a general enhancing effect on all social emotions, since intranasal administration of oxytocin also increases envy and Schadenfreude.[105] Individuals who receive an intranasal dose of oxytocin identify facial expressions of disgust more quickly than individuals who do not receive oxytocin.[101] Facial expressions of disgust are evolutionarily linked to the idea of contagion. Thus, oxytocin increases the salience of cues that imply contamination, which leads to a faster response because these cues are especially relevant for survival. In another study, after administration of oxytocin, individuals displayed an enhanced ability to recognize expressions of fear compared to the individuals who received the placebo.[106] Oxytocin modulates fear responses by enhancing the maintenance of social memories. Rats that are genetically modified to have a surplus of oxytocin receptors display a greater fear response to a previously conditioned stressor. Oxytocin enhances the aversive social memory, leading the rat to display a greater fear response when the aversive stimulus is encountered again.[100]

Mood and depression

Oxytocin produces antidepressant-like effects in animal models of depression,[107] and a deficit of it may be involved in the pathophysiology of depression in humans.[108] The antidepressant-like effects of oxytocin are not blocked by a selective antagonist of the oxytocin receptor, suggesting that these effects are not mediated by the oxytocin receptor.[29] In accordance, unlike oxytocin, the selective non-peptide oxytocin receptor agonist WAY-267,464 does not produce antidepressant-like effects, at least in the tail suspension test.[109] In contrast to WAY-267,464, carbetocin, a close analogue of oxytocin and peptide oxytocin receptor agonist, notably does produce antidepressant-like effects in animals.[109] As such, the antidepressant-like effects of oxytocin may be mediated by modulation of a different target, perhaps the vasopressin V1A receptor where oxytocin is known to weakly bind as an agonist.[110][111]

Oxytocin mediates the antidepressant-like effects of sexual activity.[112][113] A drug for sexual dysfunction, sildenafil enhances electrically evoked oxytocin release from the pituitary gland.[114] In accordance, it may have promise as an antidepressant.[107][115]

Sex differences

It has been shown that oxytocin differentially affects males and females. Females who are administered oxytocin are overall faster in responding to socially relevant stimuli than males who received oxytocin.[101][116] Additionally, after the administration of oxytocin, females show increased amygdala activity in response to threatening scenes; however, males do not show increased amygdala activation. This phenomenon can be explained by looking at the role of gonadal hormones, specifically estrogen, which modulate the enhanced threat processing seen in females. Estrogen has been shown to stimulate the release of oxytocin from the hypothalamus and promote receptor binding in the amygdala.[116]

It has also been shown that testosterone directly suppresses oxytocin in mice.[117] This has been hypothesized to have evolutionary significance. With oxytocin suppressed, activities such as hunting and attacking invaders would be less mentally difficult as oxytocin is strongly associated with empathy.[118]

Social

- Affecting generosity by increasing empathy during perspective taking: In a neuroeconomics experiment, intranasal oxytocin increased generosity in the Ultimatum Game by 80%, but had no effect in the Dictator Game that measures altruism. Perspective-taking is not required in the Dictator Game, but the researchers in this experiment explicitly induced perspective-taking in the Ultimatum Game by not identifying to participants into which role they would be placed.[119] Serious methodological questions have arisen, however, with regard to the role of oxytocin in trust and generosity.[120] Empathy in healthy males has been shown to be increased after intranasal oxytocin[118][121] This is most likely due to the effect of oxytocin in enhancing eye gaze.[122] There is some discussion about which aspect of empathy oxytocin might alter – for example, cognitive vs. emotional empathy.[123] While studying wild chimpanzees, it was noted that after a chimpanzee shared food with a non-kin related chimpanzee, the subjects' levels of oxytocin increased, as measured through their urine. In comparison to other cooperative activities between chimpanzees that were monitored including grooming, food sharing generated higher levels of oxytocin. This comparatively higher level of oxytocin after food sharing parallels the increased level of oxytocin in nursing mothers, sharing nutrients with their kin.[124]

- Trust is increased by oxytocin.[125][126][127][128] Study found that with the oxytocin nasal spray, people place more trust to strangers in handling their money.[125][129] Disclosure of emotional events is a sign of trust in humans. When recounting a negative event, humans who receive intranasal oxytocin share more emotional details and stories with more emotional significance.[127] Humans also find faces more trustworthy after receiving intranasal oxytocin. In a study, participants who received intranasal oxytocin viewed photographs of human faces with neutral expressions and found them to be more trustworthy than those who did not receive oxytocin.[126] This may be because oxytocin reduces the fear of social betrayal in humans.[130] Even after experiencing social alienation by being excluded from a conversation, humans who received oxytocin scored higher in trust on the Revised NEO Personality Inventory.[128] Moreover, in a risky investment game, experimental subjects given nasally administered oxytocin displayed "the highest level of trust" twice as often as the control group. Subjects who were told they were interacting with a computer showed no such reaction, leading to the conclusion that oxytocin was not merely affecting risk aversion.[131] When there is a reason to be distrustful, such as experiencing betrayal, differing reactions are associated with oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) differences. Those with the CT haplotype experience a stronger reaction, in the form of anger, to betrayal.[132]

- Romantic attachment: In some studies, high levels of plasma oxytocin have been correlated with romantic attachment. For example, if a couple is separated for a long period of time, anxiety can increase due to the lack of physical affection. Oxytocin may aid romantically attached couples by decreasing their feelings of anxiety when they are separated.[133]

- Group-serving dishonesty/deception: In a carefully controlled study exploring the biological roots of immoral behavior, oxytocin was shown to promote dishonesty when the outcome favored the group to which an individual belonged instead of just the individual.[134]

- Oxytocin affects social distance between adult males and females, and may be responsible at least in part for romantic attraction and subsequent monogamous pair bonding. An oxytocin nasal spray caused men in a monogamous relationship, but not single men, to increase the distance between themselves and an attractive woman during a first encounter by 10 to 15 centimeters. The researchers suggested that oxytocin may help promote fidelity within monogamous relationships.[135] For this reason, it is sometimes referred to as the "bonding hormone". There is some evidence that oxytocin promotes ethnocentric behavior, incorporating the trust and empathy of in-groups with their suspicion and rejection of outsiders.[92] Furthermore, genetic differences in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) have been associated with maladaptive social traits such as aggressive behavior.[136]

- Social behavior[92][137] and wound healing: Oxytocin is also thought to modulate inflammation by decreasing certain cytokines.[138] Thus, the increased release in oxytocin following positive social interactions has the potential to improve wound healing. A study by Marazziti and colleagues used heterosexual couples to investigate this possibility. They found increases in plasma oxytocin following a social interaction were correlated with faster wound healing. They hypothesized this was due to oxytocin reducing inflammation, thus allowing the wound to heal more quickly. This study provides preliminary evidence that positive social interactions may directly influence aspects of health.[139] According to a study published in 2014, silencing of oxytocin receptor interneurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of female mice resulted in loss of social interest in male mice during the sexually receptive phase of the estrous cycle.[140] Oxytocin evokes feelings of contentment, reductions in anxiety, and feelings of calmness and security when in the company of the mate.[133] This suggests oxytocin may be important for the inhibition of the brain regions associated with behavioral control, fear, and anxiety, thus allowing orgasm to occur. Research has also demonstrated that oxytocin can decrease anxiety and protect against stress, particularly in combination with social support.[141][142] It is found, that endocannabinoid signaling mediates oxytocin-driven social reward.[143] According to a study published in 2008, its results pointed to how a lack of oxytocin in mice saw a abnormalities in emotional behavior.[144] Another study in conducted in 2014, saw similar results with a variation in the oxytocin receptor is connected with dopamine transporter and how levels of oxytocin are dependent on the levels of dopamine transporter levels.[145] One study explored the effects of low levels of oxytocin and the other on possible explanation of what affects oxytocin receptors. As a lack of social skills and proper emotional behavior are common signs of Autism, low levels of oxytocin could become a new sign for individuals that fall into the Autism Spectrum.

Chemistry

Oxytocin is a peptide of nine amino acids (a nonapeptide) in the sequence cysteine-tyrosine-isoleucine-glutamine-asparagine-cysteine-proline-leucine-glycine-amide (Cys – Tyr – Ile – Gln – Asn – Cys – Pro – Leu – Gly – NH2, or CYIQNCPLG-NH2); its C-terminus has been converted to a primary amide and a disulfide bridge joins the cysteine moieties.[146] Oxytocin has a molecular mass of 1007 Da, and one international unit (IU) of oxytocin is the equivalent of 1.68 μg of pure peptide.[147]

While the structure of oxytocin is highly conserved in placental mammals, a novel structure of oxytocin was reported in 2011 in marmosets, tamarins, and other new world primates. Genomic sequencing of the gene for oxytocin revealed a single in-frame mutation (thymine for cytosine) which results in a single amino acid substitution at the 8-position (proline for leucine).[148] Since this original Lee et al. paper, two other laboratories have confirmed Pro8-OT and documented additional oxytocin structural variants in this primate taxon. Vargas-Pinilla et al. sequenced the coding regions of the OXT gene in other genera in new world primates and identified the following variants in addition to Leu8- and Pro8-OT: Ala8-OT, Thr8-OT, and Val3/Pro8-OT.[149] Ren et al. identified a variant further, Phe2-OT in howler monkeys.[150]

The biologically active form of oxytocin, commonly measured by RIA and/or HPLC techniques, is the oxidized octapeptide oxytocin disulfide, but oxytocin also exists as a reduced straight-chain (non-cyclic) dithiol nonapeptide called oxytoceine.[151] It has been theorized that oxytoceine may act as a free radical scavenger, as donating an electron to a free radical allows oxytoceine to be re-oxidized to oxytocin via the dehydroascorbate / ascorbate redox couple.[152]

Recent advances in analytical instrumental techniques highlighted the importance of liquid chromatography (LC) coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) for measuring oxytocin levels in various samples derived from biological sources. Most of these studies optimized the oxytocin quantification in electrospray ionization (ESI) positive mode, using [M+H]+ as the parent ion at mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) 1007.4 and the fragment ions as diagnostic peaks at m/z 991.0,[153] m/z 723.2[154] and m/z 504.2.[155] These important ion selections paved the way for the development of current methods of oxytocin quantification using MS instrumentation.

The structure of oxytocin is very similar to that of vasopressin. Both are nonapeptides with a single disulfide bridge, differing only by two substitutions in the amino acid sequence (differences from oxytocin bolded for clarity): Cys – Tyr – Phe – Gln – Asn – Cys – Pro – Arg – Gly – NH2.[146] Oxytocin and vasopressin were isolated and their total synthesis reported in 1954,[156] work for which Vincent du Vigneaud was awarded the 1955 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with the citation: "for his work on biochemically important sulphur compounds, especially for the first synthesis of a polypeptide hormone."[157]

Oxytocin and vasopressin are the only known hormones released by the human posterior pituitary gland to act at a distance. However, oxytocin neurons make other peptides, including corticotropin-releasing hormone and dynorphin, for example, that act locally. The magnocellular neurosecretory cells that make oxytocin are adjacent to magnocellular neurosecretory cells that make vasopressin. These are large neuroendocrine neurons which are excitable and can generate action potentials.[158]

In popular culture

"Oxytocin" is the name of the fifth song on Billie Eilish's second album Happier Than Ever.

In the novel The Fireman by Joe Hill, the hormone plays a role in neutralizing the danger posed by an infectious spore that causes a condition known as Dragonscale. If the spore enters an oxytocin-rich environment, it will enter a dormant state instead of causing its host to undergo spontaneous human combustion.

The formula for Oxytocin is displayed as written on the fingers of Nina Zilli and appears in the opening shot of her video for "Sola".

Jack (Steve Zahn), a character in the 2004 movie “Employee of the Month” explains how oxytocin performs in the female body at the 45m27s mark. A more detailed explanation on oxytocin begins at 44m40s.

See also

- Oxytocin (medication)

References

- Weisman O, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R (September 2012). "Intranasal oxytocin administration is reflected in human saliva". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 37 (9): 1582–1586. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.014. PMID 22436536. S2CID 25253083.

- Huffmeijer R, Alink LR, Tops M, Grewen KM, Light KC, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Ijzendoorn MH (2012). "Salivary levels of oxytocin remain elevated for more than two hours after intranasal oxytocin administration". Neuro Endocrinology Letters. 33 (1): 21–25. PMID 22467107.

- Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (41 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2015. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-7020-6851-5.

- Audunsdottir K, Quintana DS (2022-01-25). "Oxytocin's dynamic role across the lifespan". Aging Brain. 2: 100028. doi:10.1016/j.nbas.2021.100028. ISSN 2589-9589. S2CID 246314607.

- Leng G, Leng RI (November 2021). "Oxytocin: A citation network analysis of 10 000 papers". Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 33 (11): e13014. doi:10.1111/jne.13014. PMID 34328668. S2CID 236516186.

- Francis DD, Young LJ, Meaney MJ, Insel TR (May 2002). "Naturally occurring differences in maternal care are associated with the expression of oxytocin and vasopressin (V1a) receptors: gender differences". Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 14 (5): 349–53. doi:10.1046/j.0007-1331.2002.00776.x. PMID 12000539. S2CID 16005801.

- Gainer H, Fields RL, House SB (October 2001). "Vasopressin gene expression: experimental models and strategies". Experimental Neurology. 171 (2): 190–9. doi:10.1006/exnr.2001.7769. PMID 11573971. S2CID 25718623.

- Rogers K. "Oxytocin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Chiras DD (2012). Human Biology (7th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-7637-8345-7.

- Human Evolutionary Biology. Cambridge University Press. 2010. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-139-78900-4.

- "oxytocic - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. 14 October 2019. Retrieved 2021-08-05.

- "oxytocin - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. 15 July 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-05.

- Dale HH (May 1906). "On some physiological actions of ergot". The Journal of Physiology. 34 (3): 163–206. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1906.sp001148. PMC 1465771. PMID 16992821.

- Lee HJ, Macbeth AH, Pagani JH, Young WS (June 2009). "Oxytocin: the great facilitator of life". Progress in Neurobiology. 88 (2): 127–151. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.04.001. PMC 2689929. PMID 19482229.

- Ott I, Scott JC (1910). "The action of infundibulin upon the mammary secretion". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 8 (2): 48–49. doi:10.3181/00379727-8-27. S2CID 87519246.

- Schafer EA, Mackenzie K (July 1911). "The Action of Animal Extracts on Milk Secretion". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 84 (568): 16–22. Bibcode:1911RSPSB..84...16S. doi:10.1098/rspb.1911.0042.

- Corey EJ (2012). "Oxytocin". Molecules and Medicine. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-36173-3.

- Du Vigneaud V, Ressler C, Trippett S (December 1953). "The sequence of amino acids in oxytocin, with a proposal for the structure of oxytocin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 205 (2): 949–957. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)49238-1. PMID 13129273.

- Lee HJ, Macbeth AH, Pagani JH, Young WS (June 2009). "Oxytocin: the great facilitator of life". Progress in Neurobiology. US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. 88 (2): 127–151. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.04.001. PMC 2689929. PMID 19482229.

- du Vigneaud V, Ressler C, Swan JM, Roberts CW, Katsoyannis PG, Gordon S (1953). "The synthesis of an octapeptide amide with the hormonal activity of oxytocin". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 75 (19): 4879–80. doi:10.1021/ja01115a553.

- du Vigneaud V, Ressler C, Swan JM, Roberts CW, Katsoyannis PG (1954). "The Synthesis of Oxytocin1". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 76 (12): 3115–21. doi:10.1021/ja01641a004.

- Du Vigneaud V (June 1956). "Trail of sulfur research: from insulin to oxytocin". Science. 123 (3205): 967–974. Bibcode:1956Sci...123..967D. doi:10.1126/science.123.3205.967. PMID 13324123.

- Iphigenia Vourvidou-Photaki: Biographical Statement and Scientific Work (PDF) (in Greek). Athens: F. Konstantinidis & K. Mihalas. 1968. pp. 5–42.

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000101405 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000027301 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Goldstein I, Meston CM, Davis S, Traish A (17 November 2005). Women's Sexual Function and Dysfunction: Study, Diagnosis and Treatment. CRC Press. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-1-84214-263-9.

- Acevedo-Rodriguez A, Mani SK, Handa RJ (2015). "Oxytocin and Estrogen Receptor β in the Brain: An Overview". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 6: 160. doi:10.3389/fendo.2015.00160. PMC 4606117. PMID 26528239.

- Sausville E, Carney D, Battey J (August 1985). "The human vasopressin gene is linked to the oxytocin gene and is selectively expressed in a cultured lung cancer cell line". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 260 (18): 10236–10241. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)39236-0. PMID 2991279.

- Repaske DR, Phillips JA, Kirby LT, Tze WJ, D'Ercole AJ, Battey J (March 1990). "Molecular analysis of autosomal dominant neurohypophyseal diabetes insipidus". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 70 (3): 752–757. doi:10.1210/jcem-70-3-752. PMID 1968469.

- Summar ML, Phillips JA, Battey J, Castiglione CM, Kidd KK, Maness KJ, et al. (June 1990). "Linkage relationships of human arginine vasopressin-neurophysin-II and oxytocin-neurophysin-I to prodynorphin and other loci on chromosome 20". Molecular Endocrinology. 4 (6): 947–950. doi:10.1210/mend-4-6-947. PMID 1978246.

- Brownstein MJ, Russell JT, Gainer H (January 1980). "Synthesis, transport, and release of posterior pituitary hormones". Science. 207 (4429): 373–378. Bibcode:1980Sci...207..373B. doi:10.1126/science.6153132. PMID 6153132.

- Sheldrick EL, Flint AP (July 1989). "Post-translational processing of oxytocin-neurophysin prohormone in the ovine corpus luteum: activity of peptidyl glycine alpha-amidating mono-oxygenase and concentrations of its cofactor, ascorbic acid". The Journal of Endocrinology. 122 (1): 313–322. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1220313. PMID 2769155.

- Luck MR, Jungclas B (September 1987). "Catecholamines and ascorbic acid as stimulators of bovine ovarian oxytocin secretion" (PDF). The Journal of Endocrinology. 114 (3): 423–430. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1140423. PMID 3668432. S2CID 24630906. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-22.

- Hornig D (September 1975). "Distribution of ascorbic acid, metabolites and analogues in man and animals". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 258 (1): 103–118. Bibcode:1975NYASA.258..103H. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb29271.x. PMID 1106295. S2CID 22881895.

- Tsujimoto M, Hattori A (August 2005). "The oxytocinase subfamily of M1 aminopeptidases". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1751 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.09.011. PMID 16054015.

- Nomura S, Ito T, Yamamoto E, Sumigama S, Iwase A, Okada M, et al. (August 2005). "Gene regulation and physiological function of placental leucine aminopeptidase/oxytocinase during pregnancy". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1751 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.04.006. PMID 15894523.

- Mizutani S, Yokosawa H, Tomoda Y (July 1992). "Degradation of oxytocin by the human placenta: effect of selective inhibitors" (PDF). Acta Endocrinologica. 127 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1530/acta.0.1270076. PMID 1355623. S2CID 21289122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-24.

- Meisenberg G, Simmons WH (1984). "Amastatin potentiates the behavioral effects of vasopressin and oxytocin in mice". Peptides. 5 (3): 535–539. doi:10.1016/0196-9781(84)90083-4. PMID 6540873. S2CID 3881661.

- Stancampiano R, Melis MR, Argiolas A (1991). "Proteolytic conversion of oxytocin by brain synaptic membranes: role of aminopeptidases and endopeptidases". Peptides. 12 (5): 1119–1125. doi:10.1016/0196-9781(91)90068-z. PMID 1800950. S2CID 36706540.

- Itoh C, Watanabe M, Nagamatsu A, Soeda S, Kawarabayashi T, Shimeno H (January 1997). "Two molecular species of oxytocinase (L-cystine aminopeptidase) in human placenta: purification and characterization". Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 20 (1): 20–24. doi:10.1248/bpb.20.20. PMID 9013800.

- Sukhov RR, Walker LC, Rance NE, Price DL, Young WS (November 1993). "Vasopressin and oxytocin gene expression in the human hypothalamus". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 337 (2): 295–306. doi:10.1002/cne.903370210. PMID 8277003. S2CID 35174328.

- Ross HE, Cole CD, Smith Y, Neumann ID, Landgraf R, Murphy AZ, Young LJ (September 2009). "Characterization of the oxytocin system regulating affiliative behavior in female prairie voles". Neuroscience. 162 (4): 892–903. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.055. PMC 2744157. PMID 19482070.

- Landgraf R, Neumann ID (2004). "Vasopressin and oxytocin release within the brain: a dynamic concept of multiple and variable modes of neuropeptide communication". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 25 (3–4): 150–176. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.05.001. PMID 15589267. S2CID 30507377.

- Baribeau DA, Anagnostou E (2015). "Oxytocin and vasopressin: linking pituitary neuropeptides and their receptors to social neurocircuits". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 9: 335. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00335. PMC 4585313. PMID 26441508.

- Wathes DC, Swann RW (May 1982). "Is oxytocin an ovarian hormone?". Nature. 297 (5863): 225–227. Bibcode:1982Natur.297..225W. doi:10.1038/297225a0. PMID 7078636. S2CID 4364778.

- Wathes DC, Swann RW, Pickering BT, Porter DG, Hull MG, Drife JO (August 1982). "Neurohypophysial hormones in the human ovary". Lancet. 2 (8295): 410–412. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(82)90441-X. PMID 6124806. S2CID 42282964.

- Fields PA, Eldridge RK, Fuchs AR, Roberts RF, Fields MJ (April 1983). "Human placental and bovine corpora luteal oxytocin". Endocrinology. 112 (4): 1544–1546. doi:10.1210/endo-112-4-1544. PMID 6832059.

- Guldenaar SE, Pickering BT (1985). "Immunocytochemical evidence for the presence of oxytocin in rat testis". Cell and Tissue Research. 240 (2): 485–487. doi:10.1007/BF00222364. PMID 3995564. S2CID 34325145.

- Gauquelin G, Geelen G, Louis F, Allevard AM, Meunier C, Cuisinaud G, et al. (1983). "Presence of vasopressin, oxytocin and neurophysin in the retina of mammals, effect of light and darkness, comparison with the neuropeptide content of the neurohypophysis and the pineal gland". Peptides. 4 (4): 509–515. doi:10.1016/0196-9781(83)90056-6. PMID 6647119. S2CID 3848055.

- Ang VT, Jenkins JS (April 1984). "Neurohypophysial hormones in the adrenal medulla". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 58 (4): 688–691. doi:10.1210/jcem-58-4-688. PMID 6699132.

- Geenen V, Legros JJ, Franchimont P, Baudrihaye M, Defresne MP, Boniver J (April 1986). "The neuroendocrine thymus: coexistence of oxytocin and neurophysin in the human thymus". Science. 232 (4749): 508–511. Bibcode:1986Sci...232..508G. doi:10.1126/science.3961493. hdl:2268/16909. PMID 3961493.

- Amico JA, Finn FM, Haldar J (November 1988). "Oxytocin and vasopressin are present in human and rat pancreas". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 296 (5): 303–307. doi:10.1097/00000441-198811000-00003. PMID 3195625. S2CID 20084873.

- Kukucka MA, Misra HP (1992). "HPLC determination of an oxytocin-like peptide produced by isolated guinea pig Leydig cells: stimulation by ascorbate". Archives of Andrology. 29 (2): 185–190. doi:10.3109/01485019208987723. PMID 1456839.

- Venkatesh B, Si-Hoe SL, Murphy D, Brenner S (November 1997). "Transgenic rats reveal functional conservation of regulatory controls between the Fugu isotocin and rat oxytocin genes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (23): 12462–12466. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9412462V. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.23.12462. PMC 25001. PMID 9356472.

- Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F (April 2001). "The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation" (PDF). Physiological Reviews. 81 (2): 629–683. doi:10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.629. PMID 11274341. S2CID 13265083. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-16.

- Quattropani A, Dorbais J, Covini D, Pittet PA, Colovray V, Thomas RJ, et al. (December 2005). "Discovery and development of a new class of potent, selective, orally active oxytocin receptor antagonists". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 48 (24): 7882–7905. doi:10.1021/jm050645f. PMID 16302826. S2CID 11213732.

- Holmes B (11 February 2022). "Oxytocin's effects aren't just about love". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-021122-1. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- Froemke RC, Young LJ (July 2021). "Oxytocin, Neural Plasticity, and Social Behavior". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 44 (1): 359–381. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-102320-102847. PMC 8604207. PMID 33823654.

- Human Milk and Lactation at eMedicine

- MacGill M. "What is oxytocin, and what does it do?". Medical News Today. Heath Line Media. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, et al. (November 2005). "Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (44): 16096–16101. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10216096T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505312102. PMC 1276060. PMID 16249339.

- Thackare H, Nicholson HD, Whittington K (2006-08-01). "Oxytocin--its role in male reproduction and new potential therapeutic uses". Human Reproduction Update. 12 (4): 437–448. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmk002. PMID 16436468.

- Carmichael MS, Humbert R, Dixen J, Palmisano G, Greenleaf W, Davidson JM (January 1987). "Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 64 (1): 27–31. doi:10.1210/jcem-64-1-27. PMID 3782434.

- Carmichael MS, Warburton VL, Dixen J, Davidson JM (February 1994). "Relationships among cardiovascular, muscular, and oxytocin responses during human sexual activity". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 23 (1): 59–79. doi:10.1007/BF01541618. PMID 8135652. S2CID 36539568.

- Blaicher W, Gruber D, Bieglmayer C, Blaicher AM, Knogler W, Huber JC (1999). "The role of oxytocin in relation to female sexual arousal". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 47 (2): 125–126. doi:10.1159/000010075. PMID 9949283. S2CID 43036197.

- Anderson-Hunt M, Dennerstein L (1995). "Oxytocin and female sexuality". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 40 (4): 217–221. doi:10.1159/000292340. PMID 8586300.

- Murphy MR, Seckl JR, Burton S, Checkley SA, Lightman SL (October 1987). "Changes in oxytocin and vasopressin secretion during sexual activity in men". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 65 (4): 738–741. doi:10.1210/jcem-65-4-738. PMID 3654918.

- Krüger TH, Haake P, Chereath D, Knapp W, Janssen OE, Exton MS, et al. (April 2003). "Specificity of the neuroendocrine response to orgasm during sexual arousal in men". The Journal of Endocrinology. 177 (1): 57–64. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1770057. PMID 12697037.

- Paquin J, Danalache BA, Jankowski M, McCann SM, Gutkowska J (July 2002). "Oxytocin induces differentiation of P19 embryonic stem cells to cardiomyocytes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (14): 9550–9555. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.9550P. doi:10.1073/pnas.152302499. PMC 123178. PMID 12093924.

- Jankowski M, Danalache B, Wang D, Bhat P, Hajjar F, Marcinkiewicz M, et al. (August 2004). "Oxytocin in cardiac ontogeny". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (35): 13074–13079. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10113074J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405324101. PMC 516519. PMID 15316117.

- Hartwig W (1989). Endokrynologia praktyczna. Warsaw: Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich. ISBN 978-83-200-1415-0.

- Tyzio R, Cossart R, Khalilov I, Minlebaev M, Hübner CA, Represa A, et al. (December 2006). "Maternal oxytocin triggers a transient inhibitory switch in GABA signaling in the fetal brain during delivery" (PDF). Science. 314 (5806): 1788–1792. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1788T. doi:10.1126/science.1133212. PMID 17170309. S2CID 85151049.

- Atasoy D, Betley JN, Su HH, Sternson SM (August 2012). "Deconstruction of a neural circuit for hunger". Nature. 488 (7410): 172–177. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..172A. doi:10.1038/nature11270. PMC 3416931. PMID 22801496.

- Odekunle EA, Semmens DC, Martynyuk N, Tinoco AB, Garewal AK, Patel RR, et al. (July 2019). "Ancient role of vasopressin/oxytocin-type neuropeptides as regulators of feeding revealed in an echinoderm". BMC Biology. 17 (1): 60. doi:10.1186/s12915-019-0680-2. PMC 6668147. PMID 31362737.

- Jacob S, Brune CW, Carter CS, Leventhal BL, Lord C, Cook EH (April 2007). "Association of the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) in Caucasian children and adolescents with autism". Neuroscience Letters. 417 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.001. PMC 2705963. PMID 17383819.

- Wermter AK, Kamp-Becker I, Hesse P, Schulte-Körne G, Strauch K, Remschmidt H (March 2010). "Evidence for the involvement of genetic variation in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) in the etiology of autistic disorders on high-functioning level". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 153B (2): 629–639. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.31032. PMID 19777562. S2CID 15970613.

- Dayi A, Cetin F, Sisman AR, Aksu I, Tas A, Gönenc S, Uysal N (January 2015). "The effects of oxytocin on cognitive defect caused by chronic restraint stress applied to adolescent rats and on hippocampal VEGF and BDNF levels". Medical Science Monitor. 21: 69–75. doi:10.12659/MSM.893159. PMC 4294596. PMID 25559382.

- Leuner B, Caponiti JM, Gould E (April 2012). "Oxytocin stimulates adult neurogenesis even under conditions of stress and elevated glucocorticoids". Hippocampus. 22 (4): 861–868. doi:10.1002/hipo.20947. PMC 4756590. PMID 21692136.

- Ye C, Cheng M, Ma L, Zhang T, Sun Z, Yu C, et al. (May 2022). "Oxytocin Nanogels Inhibit Innate Inflammatory Response for Early Intervention in Alzheimer's Disease". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 14 (19): 21822–21835. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c00007. PMID 35510352. S2CID 248526969.

- Vacek M (2002). "High on Fidelity: What can voles teach us about monogamy?". American Scientist. Archived from the original on October 15, 2006.

- Odendaal JS, Meintjes RA (May 2003). "Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behaviour between humans and dogs". Veterinary Journal. 165 (3): 296–301. doi:10.1016/S1090-0233(02)00237-X. PMID 12672376.

- van Leengoed E, Kerker E, Swanson HH (February 1987). "Inhibition of post-partum maternal behaviour in the rat by injecting an oxytocin antagonist into the cerebral ventricles". The Journal of Endocrinology. 112 (2): 275–282. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1120275. PMID 3819639.

- Kendrick KM (December 2004). "The neurobiology of social bonds". Journal of Neuroendocrinology. British Society for Neuroendocrinology. 16 (12): 1007–1008. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01262.x. PMID 15667456. S2CID 21635457. Archived from the original on 2009-04-29. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- Bick J, Dozier M (January 2010). "Mothers' and Children's Concentrations of Oxytocin Following Close, Physical Interactions with Biological and Non-biological Children". Developmental Psychobiology. 52 (1): 100–107. doi:10.1002/dev.20411. PMC 2953948. PMID 20953313.

- Sheng F, Liu Y, Zhou B, Zhou W, Han S (February 2013). "Oxytocin modulates the racial bias in neural responses to others' suffering". Biological Psychology. 92 (2): 380–386. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.11.018. PMID 23246533. S2CID 206109148.

- Shalvi S, De Dreu CK (April 2014). "Oxytocin promotes group-serving dishonesty". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (15): 5503–5507. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.5503S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1400724111. PMC 3992689. PMID 24706799.

- De Dreu CK, Shalvi S, Greer LL, Van Kleef GA, Handgraaf MJ (2012). "Oxytocin motivates non-cooperation in intergroup conflict to protect vulnerable in-group members". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e46751. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...746751D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046751. PMC 3492361. PMID 23144787.

- Stallen M, De Dreu CK, Shalvi S, Smidts A, Sanfey AG (2012). "The herding hormone: oxytocin stimulates in-group conformity". Psychological Science. 23 (11): 1288–1292. doi:10.1177/0956797612446026. PMID 22991128. S2CID 16255677.

- De Dreu CK, Greer LL, Van Kleef GA, Shalvi S, Handgraaf MJ (January 2011). "Oxytocin promotes human ethnocentrism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (4): 1262–1266. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.1262D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015316108. PMC 3029708. PMID 21220339.

- Ma X, Luo L, Geng Y, Zhao W, Zhang Q, Kendrick KM (2014). "Oxytocin increases liking for a country's people and national flag but not for other cultural symbols or consumer products". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 8: 266. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00266. PMC 4122242. PMID 25140135.

- Kovács GL, Sarnyai Z, Szabó G (November 1998). "Oxytocin and addiction: a review". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 23 (8): 945–962. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00064-X. PMID 9924746. S2CID 31674417.

- Thompson MR, Callaghan PD, Hunt GE, Cornish JL, McGregor IS (May 2007). "A role for oxytocin and 5-HT(1A) receptors in the prosocial effects of 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine ("ecstasy")". Neuroscience. 146 (2): 509–514. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.032. PMID 17383105. S2CID 15617471.

- Uvnäs-Moberg K, Hillegaart V, Alster P, Ahlenius S (1996). "Effects of 5-HT agonists, selective for different receptor subtypes, on oxytocin, CCK, gastrin and somatostatin plasma levels in the rat". Neuropharmacology. 35 (11): 1635–1640. doi:10.1016/S0028-3908(96)00078-0. PMID 9025112. S2CID 44375951.

- Chiodera P, Volpi R, Capretti L, Caffarri G, Magotti MG, Coiro V (April 1996). "Different effects of the serotonergic agonists buspirone and sumatriptan on the posterior pituitary hormonal responses to hypoglycemia in humans". Neuropeptides. 30 (2): 187–192. doi:10.1016/S0143-4179(96)90086-4. PMID 8771561. S2CID 13734738.

- Buisman-Pijlman FT, Sumracki NM, Gordon JJ, Hull PR, Carter CS, Tops M (April 2014). "Individual differences underlying susceptibility to addiction: Role for the endogenous oxytocin system". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 119: 22–38. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2013.09.005. PMID 24056025.

- Grillon C, Krimsky M, Charney DR, Vytal K, Ernst M, Cornwell B (September 2013). "Oxytocin increases anxiety to unpredictable threat". Molecular Psychiatry. 18 (9): 958–960. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.156. PMC 3930442. PMID 23147382.

- Guzmán YF, Tronson NC, Jovasevic V, Sato K, Guedea AL, Mizukami H, et al. (September 2013). "Fear-enhancing effects of septal oxytocin receptors". Nature Neuroscience. 16 (9): 1185–1187. doi:10.1038/nn.3465. PMC 3758455. PMID 23872596.

- Theodoridou A, Penton-Voak IS, Rowe AC (2013). "A direct examination of the effect of intranasal administration of oxytocin on approach-avoidance motor responses to emotional stimuli". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e58113. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...858113T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058113. PMC 3585234. PMID 23469148.

- Kirsch P, Esslinger C, Chen Q, Mier D, Lis S, Siddhanti S, et al. (December 2005). "Oxytocin modulates neural circuitry for social cognition and fear in humans". The Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (49): 11489–11493. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3984-05.2005. PMC 6725903. PMID 16339042.

- Huber D, Veinante P, Stoop R (April 2005). "Vasopressin and oxytocin excite distinct neuronal populations in the central amygdala". Science. 308 (5719): 245–248. Bibcode:2005Sci...308..245H. doi:10.1126/SCIENCE.1105636. PMID 15821089. S2CID 40887741.

- Viviani D, Charlet A, van den Burg E, Robinet C, Hurni N, Abatis M, et al. (July 2011). "Oxytocin selectively gates fear responses through distinct outputs from the central amygdala". Science. 333 (6038): 104–107. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..104V. doi:10.1126/SCIENCE.1201043. PMID 21719680. S2CID 20446890.

- Shamay-Tsoory SG, Fischer M, Dvash J, Harari H, Perach-Bloom N, Levkovitz Y (November 2009). "Intranasal administration of oxytocin increases envy and schadenfreude (gloating)". Biological Psychiatry. 66 (9): 864–870. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.009. PMID 19640508. S2CID 20396036.

- Fischer-Shofty M, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Harari H, Levkovitz Y (January 2010). "The effect of intranasal administration of oxytocin on fear recognition". Neuropsychologia. 48 (1): 179–184. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.09.003. PMID 19747930. S2CID 34778485.

- Matsuzaki M, Matsushita H, Tomizawa K, Matsui H (November 2012). "Oxytocin: a therapeutic target for mental disorders". The Journal of Physiological Sciences. 62 (6): 441–444. doi:10.1007/s12576-012-0232-9. PMID 23007624. S2CID 17860416.

- McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Abizaid A, Anisman H (September 2014). "Making room for oxytocin in understanding depression". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 45: 305–322. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.07.005. PMID 25025656. S2CID 32062939.

- Shalev I, Ebstein RP (2015). Social Hormones and Human Behavior: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go from Here. Frontiers Media SA. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-2-88919-407-0.

- Hicks C, Ramos L, Reekie T, Misagh GH, Narlawar R, Kassiou M, McGregor IS (June 2014). "Body temperature and cardiac changes induced by peripherally administered oxytocin, vasopressin and the non-peptide oxytocin receptor agonist WAY 267,464: a biotelemetry study in rats". British Journal of Pharmacology. 171 (11): 2868–2887. doi:10.1111/bph.12613. PMC 4243861. PMID 24641248.

- Manning M, Misicka A, Olma A, Bankowski K, Stoev S, Chini B, et al. (April 2012). "Oxytocin and vasopressin agonists and antagonists as research tools and potential therapeutics". Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 24 (4): 609–628. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012.02303.x. PMC 3490377. PMID 22375852.

- Matsushita H, Tomizawa K, Okimoto N, Nishiki T, Ohmori I, Matsui H (October 2010). "Oxytocin mediates the antidepressant effects of mating behavior in male mice". Neuroscience Research. 68 (2): 151–153. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2010.06.007. PMID 20600375. S2CID 207152048.

- Phan J, Alhassen L, Argelagos A, Alhassen W, Vachirakorntong B, Lin Z, et al. (August 2020). "Mating and parenting experiences sculpture mood-modulating effects of oxytocin-MCH signaling". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 13611. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1013611P. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-70667-x. PMC 7423941. PMID 32788646.

- Zhang Z, Klyachko V, Jackson MB (October 2007). "Blockade of phosphodiesterase Type 5 enhances rat neurohypophysial excitability and electrically evoked oxytocin release". The Journal of Physiology. 584 (Pt 1): 137–147. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139303. PMC 2277045. PMID 17690141.

- Matsushita H, Matsuzaki M, Han XJ, Nishiki TI, Ohmori I, Michiue H, et al. (January 2012). "Antidepressant-like effect of sildenafil through oxytocin-dependent cyclic AMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation". Neuroscience. 200: 13–18. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.11.001. PMID 22088430. S2CID 12502639.

- Lischke A, Gamer M, Berger C, Grossmann A, Hauenstein K, Heinrichs M, et al. (September 2012). "Oxytocin increases amygdala reactivity to threatening scenes in females". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 37 (9): 1431–1438. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.01.011. PMID 22365820. S2CID 7981815.

- Okabe S, Kitano K, Nagasawa M, Mogi K, Kikusui T (June 2013). "Testosterone inhibits facilitating effects of parenting experience on parental behavior and the oxytocin neural system in mice". Physiology & Behavior. 118: 159–164. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.05.017. PMID 23685236. S2CID 46790892.

- Hurlemann R, Patin A, Onur OA, Cohen MX, Baumgartner T, Metzler S, et al. (April 2010). "Oxytocin enhances amygdala-dependent, socially reinforced learning and emotional empathy in humans". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (14): 4999–5007. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5538-09.2010. PMC 6632777. PMID 20371820.

- Zak PJ, Stanton AA, Ahmadi S (November 2007). Brosnan S (ed.). "Oxytocin increases generosity in humans". PLOS ONE. 2 (11): e1128. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2.1128Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001128. PMC 2040517. PMID 17987115.

- Conlisk J (2011). "Professor Zak's empirical studies on trust and oxytocin". J Econ Behav Organizat. 78 (1–2): 160–66. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2011.01.002.

- Domes G, Heinrichs M, Michel A, Berger C, Herpertz SC (March 2007). "Oxytocin improves "mind-reading" in humans". Biological Psychiatry. 61 (6): 731–733. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.015. PMID 17137561. S2CID 3125539.

- Guastella AJ, Mitchell PB, Dadds MR (January 2008). "Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces". Biological Psychiatry. 63 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.026. PMID 17888410. S2CID 11974058.

- Singer T, Snozzi R, Bird G, Petrovic P, Silani G, Heinrichs M, Dolan RJ (December 2008). "Effects of oxytocin and prosocial behavior on brain responses to direct and vicariously experienced pain". Emotion. 8 (6): 781–791. doi:10.1037/a0014195. PMC 2672051. PMID 19102589.

- Wittig RM, Crockford C, Deschner T, Langergraber KE, Ziegler TE, Zuberbühler K (March 2014). "Food sharing is linked to urinary oxytocin levels and bonding in related and unrelated wild chimpanzees". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 281 (1778): 20133096. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.3096. PMC 3906952. PMID 24430853.

- Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E (June 2005). "Oxytocin increases trust in humans". Nature. 435 (7042): 673–676. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..673K. doi:10.1038/nature03701. PMID 15931222. S2CID 1234727.

- Theodoridou A, Rowe AC, Penton-Voak IS, Rogers PJ (June 2009). "Oxytocin and social perception: oxytocin increases perceived facial trustworthiness and attractiveness". Hormones and Behavior. 56 (1): 128–132. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.019. PMID 19344725. S2CID 12639878.

- Lane A, Luminet O, Rimé B, Gross JJ, de Timary P, Mikolajczak M (2013). "Oxytocin increases willingness to socially share one's emotions". International Journal of Psychology. 48 (4): 676–681. doi:10.1080/00207594.2012.677540. PMID 22554106.

- Cardoso C, Ellenbogen MA, Serravalle L, Linnen AM (November 2013). "Stress-induced negative mood moderates the relation between oxytocin administration and trust: evidence for the tend-and-befriend response to stress?". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 38 (11): 2800–2804. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.05.006. PMID 23768973. S2CID 25090544.

- Carey B (2005-06-02). "Hormone Dose May Increase People's Trust in Strangers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-07-22.

- Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E (May 2008). "Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans". Neuron. 58 (4): 639–650. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.009. PMID 18498743. S2CID 1432797.

- Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E (June 2005). "Oxytocin increases trust in humans". Nature. 435 (7042): 673–676. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..673K. doi:10.1038/nature03701. PMID 15931222. S2CID 1234727.

- Tabak BA, McCullough ME, Carver CS, Pedersen EJ, Cuccaro ML (June 2014). "Variation in oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) polymorphisms is associated with emotional and behavioral reactions to betrayal". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 9 (6): 810–816. doi:10.1093/scan/nst042. PMC 4040089. PMID 23547247.

- Marazziti D, Dell'Osso B, Baroni S, Mungai F, Catena M, Rucci P, et al. (October 2006). "A relationship between oxytocin and anxiety of romantic attachment". Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2 (1): 28. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-2-28. PMC 1621060. PMID 17034623.

- Shalvi S, De Dreu CK (April 2014). "Oxytocin promotes group-serving dishonesty". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (15): 5503–5507. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.5503S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1400724111. PMC 3992689. PMID 24706799.

- Melissa Hogenboom (2 April 2014). "'Love drug' makes group members lie more". BBC News.

- Scheele D, Striepens N, Güntürkün O, Deutschländer S, Maier W, Kendrick KM, Hurlemann R (November 2012). "Oxytocin modulates social distance between males and females". The Journal of Neuroscience. 32 (46): 16074–16079. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2755-12.2012. PMC 6794013. PMID 23152592.

- Malik AI, Zai CC, Abu Z, Nowrouzi B, Beitchman JH (July 2012). "The role of oxytocin and oxytocin receptor gene variants in childhood-onset aggression". Genes, Brain and Behavior. 11 (5): 545–551. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00776.x. PMID 22372486. S2CID 38807759.

- Zak PJ, Kurzban R, Matzner WT (December 2004). "The neurobiology of trust". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1032 (1): 224–227. Bibcode:2004NYASA1032..224Z. doi:10.1196/annals.1314.025. PMID 15677415. S2CID 45599465.

- Buemann B, Marazziti D, Uvnäs-Moberg K (June 2021). "Can intravenous oxytocin infusion counteract hyperinflammation in COVID-19 infected patients?". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 22 (5): 387–398. doi:10.1080/15622975.2020.1814408. PMID 32914674. S2CID 221623635.

- Gouin JP, Carter CS, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Loving TJ, et al. (August 2010). "Marital behavior, oxytocin, vasopressin, and wound healing". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 35 (7): 1082–1090. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.01.009. PMC 2888874. PMID 20144509.

- Nakajima M, Görlich A, Heintz N (October 2014). "Oxytocin modulates female sociosexual behavior through a specific class of prefrontal cortical interneurons". Cell. 159 (2): 295–305. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.020. PMC 4206218. PMID 25303526.

- Marie-Therese Walsh (2014-10-09). ""Love Hormone" Oxytocin Regulates Sociosexual Behavior in Female Mice". SciGuru. Archived from the original on 2014-10-13.

- Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C, Ehlert U (December 2003). "Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress". Biological Psychiatry. 54 (12): 1389–1398. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00465-7. PMID 14675803. S2CID 20632786.

- Matsushita H, Latt HM, Koga Y, Nishiki T, Matsui H (October 2019). "Oxytocin and Stress: Neural Mechanisms, Stress-Related Disorders, and Therapeutic Approaches". Neuroscience. 417: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.07.046. PMID 31400490. S2CID 199527439.

- Wei D, Lee D, Cox CD, Karsten CA, Peñagarikano O, Geschwind DH, et al. (November 2015). "Endocannabinoid signaling mediates oxytocin-driven social reward". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (45): 14084–14089. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214084W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509795112. PMC 4653148. PMID 26504214.

- Lerer E, Levi S, Salomon S, Darvasi A, Yirmiya N, Ebstein RP (October 2008). "Association between the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) gene and autism: relationship to Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales and cognition". Molecular Psychiatry. 13 (10): 980–988. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002087. PMID 17893705. S2CID 19513481.

- Chang WH, Lee IH, Chen KC, Chi MH, Chiu NT, Yao WJ, et al. (September 2014). "Oxytocin receptor gene rs53576 polymorphism modulates oxytocin-dopamine interaction and neuroticism traits--a SPECT study". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 47: 212–220. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.05.020. PMID 25001970. S2CID 22163043.

- Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE (2012). Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1833. ISBN 978-1455759422.

- "WHO International Standard OXYTOCIN 4th International Standard NIBSC code: 76/575: Instructions for use (Version 4.0, Dated 30/04/2013)" (PDF). Nibsc.org. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Lee AG, Cool DR, Grunwald WC, Neal DE, Buckmaster CL, Cheng MY, et al. (August 2011). "A novel form of oxytocin in New World monkeys". Biology Letters. 7 (4): 584–587. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0107. PMC 3130245. PMID 21411453.

- Vargas-Pinilla P, Paixão-Côrtes VR, Paré P, Tovo-Rodrigues L, Vieira CM, Xavier A, et al. (January 2015). "Evolutionary pattern in the OXT-OXTR system in primates: coevolution and positive selection footprints". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (1): 88–93. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112...88V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419399112. PMC 4291646. PMID 25535371.

- Ren D, Lu G, Moriyama H, Mustoe AC, Harrison EB, French JA (2015). "Genetic diversity in oxytocin ligands and receptors in New World monkeys". PLOS ONE. 10 (5): e0125775. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1025775R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125775. PMC 4418824. PMID 25938568.

- du Vigneaud V (2006). "Experiences in the Polypeptide Field: Insulin to Oxytocin". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 88 (3): 537–48. Bibcode:1960NYASA..88..537V. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb20052.x. S2CID 86315750.

- Kukucka MA (1993-04-18). Mechanisms by which hypoxia augments Leydig cell viability and differentiated cell function in vitro (PhD thesis). Virginia Tech. hdl:10919/38407.

- Moriyama E, Kataoka H (2015-06-30). "Automated Analysis of Oxytocin by On-Line in-Tube Solid-Phase Microextraction Coupled with Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry". Chromatography. 2 (3): 382–391. doi:10.3390/chromatography2030382. ISSN 2227-9075.

- Wang L, Marti DW, Anderson RE (August 2019). "Development and Validation of a Simple LC-MS Method for the Quantification of Oxytocin in Dog Saliva". Molecules. 24 (17): 3079. doi:10.3390/molecules24173079. PMC 6749683. PMID 31450590.

- Franke AA, Li X, Menden A, Lee MR, Lai JF (January 2019). "Oxytocin analysis from human serum, urine, and saliva by orbitrap liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry". Drug Testing and Analysis. 11 (1): 119–128. doi:10.1002/dta.2475. PMC 6349498. PMID 30091853.

- Du Vigneaud V, Ressler C, Swan JM, Roberts CW, Katsoyannis PG (1954). "The Synthesis of Oxytocin". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 76 (12): 3115–21. doi:10.1021/ja01641a004.

- "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1955". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- Leng G, Brown CH, Russell JA (April 1999). "Physiological pathways regulating the activity of magnocellular neurosecretory cells". Progress in Neurobiology. 57 (6): 625–655. doi:10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00072-0. PMID 10221785. S2CID 240663.

Further reading

- Caldwell HK, Young WS (2006). "Oxytocin and Vasopressin: Genetics and Behavioral Implications" (PDF). In Abel L, Lim R (eds.). Handbook of neurochemistry and molecular neurobiology. Berlin: Springer. pp. 573–607. ISBN 978-0-387-30348-2.

- Schmitz S, Höppner G, eds. (2014). "Oxytocin as proximal cause of 'maternal instinct': weak science, post-feminism, and the hormones of mystique". Gendered neurocultures: feminist and queer perspectives on current brain discourses. challenge GENDER, 2. Wien: Zaglossus. ISBN 978-3902902122.

- Yong E (13 November 2015). "The weak science behind the wrongly named moral molecule". The Atlantic..

External links

Media related to Oxytocin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Oxytocin at Wikimedia Commons