Sulfur dioxide

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Sulfur dioxide | |

| Other names

Sulfurous anhydride Sulfur(IV) oxide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

Beilstein Reference |

3535237 |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.359 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E220 (preservatives) |

Gmelin Reference |

1443 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Sulfur+dioxide |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1079, 2037 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| SO 2 | |

| Molar mass | 64.066 g mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless and pungent gas |

| Odor | Pungent; similar to a just-struck match[1] |

| Density | 2.6288 kg m−3 |

| Melting point | −72 °C; −98 °F; 201 K |

| Boiling point | −10 °C (14 °F; 263 K) |

| 94 g/L[2] forms sulfurous acid | |

| Vapor pressure | 237.2 kPa |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~1.81 |

| Basicity (pKb) | ~12.19 |

| −18.2·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Viscosity | 12.82 μPa·s[3] |

| Structure | |

| C2v | |

| Digonal | |

Molecular shape |

Dihedral |

Dipole moment |

1.62 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar entropy (S⦵298) |

248.223 J K−1 mol−1 |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−296.81 kJ mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

Hazard statements |

H314, H331[4] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LC50 (median concentration) |

3000 ppm (mouse, 30 min) 2520 ppm (rat, 1 hr)[5] |

LCLo (lowest published) |

993 ppm (rat, 20 min) 611 ppm (rat, 5 hr) 764 ppm (mouse, 20 min) 1000 ppm (human, 10 min) 3000 ppm (human, 5 min)[5] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 5 ppm (13 mg/m3)[6] |

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 2 ppm (5 mg/m3) ST 5 ppm (13 mg/m3)[6] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

100 ppm[6] |

| Related compounds | |

| Sulfur monoxide Sulfur trioxide | |

Related compounds |

Ozone Selenium dioxide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula SO

2. It is a toxic gas responsible for the smell of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic activity and is produced as a by-product of copper extraction and the burning of sulfur-bearing fossil fuels. Sulfur dioxide has a pungent smell like nitric acid.

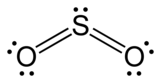

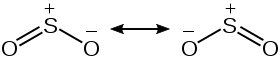

Structure and bonding

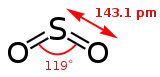

SO2 is a bent molecule with C2v symmetry point group. A valence bond theory approach considering just s and p orbitals would describe the bonding in terms of resonance between two resonance structures.

The sulfur–oxygen bond has a bond order of 1.5. There is support for this simple approach that does not invoke d orbital participation.[7] In terms of electron-counting formalism, the sulfur atom has an oxidation state of +4 and a formal charge of +1.

Occurrence

Sulfur dioxide is found on Earth and exists in very small concentrations and in the atmosphere at about 1 ppm.[8][9]

On other planets, sulfur dioxide can be found in various concentrations, the most significant being the atmosphere of Venus, where it is the third-most abundant atmospheric gas at 150 ppm. There, it reacts with water to form clouds of sulfuric acid, and is a key component of the planet's global atmospheric sulfur cycle and contributes to global warming.[10] It has been implicated as a key agent in the warming of early Mars, with estimates of concentrations in the lower atmosphere as high as 100 ppm,[11] though it only exists in trace amounts. On both Venus and Mars, as on Earth, its primary source is thought to be volcanic. The atmosphere of Io, a natural satellite of Jupiter, is 90% sulfur dioxide[12] and trace amounts are thought to also exist in the atmosphere of Jupiter.

As an ice, it is thought to exist in abundance on the Galilean moons—as subliming ice or frost on the trailing hemisphere of Io,[13] and in the crust and mantle of Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, possibly also in liquid form and readily reacting with water.[14]

Production

Sulfur dioxide is primarily produced for sulfuric acid manufacture (see contact process). In the United States in 1979, 23.6 million metric tons (26 million U.S. short tons) of sulfur dioxide were used in this way, compared with 150,000 metric tons (165,347 U.S. short tons) used for other purposes. Most sulfur dioxide is produced by the combustion of elemental sulfur. Some sulfur dioxide is also produced by roasting pyrite and other sulfide ores in air.[15]

Combustion routes

Sulfur dioxide is the product of the burning of sulfur or of burning materials that contain sulfur:

- S + O2 → SO2, ΔH = −297 kJ/mol

To aid combustion, liquified sulfur (140–150 °C, 284-302 °F) is sprayed through an atomizing nozzle to generate fine drops of sulfur with a large surface area. The reaction is exothermic, and the combustion produces temperatures of 1000–1600 °C (1832–2912 °F). The significant amount of heat produced is recovered by steam generation that can subsequently be converted to electricity.[15]

The combustion of hydrogen sulfide and organosulfur compounds proceeds similarly. For example:

- 2 H2S + 3 O2 → 2 H2O + 2 SO2

The roasting of sulfide ores such as pyrite, sphalerite, and cinnabar (mercury sulfide) also releases SO2:[16]

- 4 FeS2 + 11 O2 → 2 Fe2O3 + 8 SO2

- 2 ZnS + 3 O2 → 2 ZnO + 2 SO2

- HgS + O2 → Hg + SO2

- 4 FeS + 7O2 → 2 Fe2O3 + 4 SO2

A combination of these reactions is responsible for the largest source of sulfur dioxide, volcanic eruptions. These events can release millions of tons of SO2.

Reduction of higher oxides

Sulfur dioxide can also be a byproduct in the manufacture of calcium silicate cement; CaSO4 is heated with coke and sand in this process:

- 2 CaSO4 + 2 SiO2 + C → 2 CaSiO3 + 2 SO2 + CO2

Until the 1970s, commercial quantities of sulfuric acid and cement were produced by this process in Whitehaven, England. Upon being mixed with shale or marl, and roasted, the sulfate liberated sulfur dioxide gas, used in sulfuric acid production, the reaction also produced calcium silicate, a precursor in cement production.[17]

On a laboratory scale, the action of hot concentrated sulfuric acid on copper turnings produces sulfur dioxide.

- Cu + 2 H2SO4 → CuSO4 + SO2 + 2 H2O

From sulfites

Sulfites results by the action of aqueous base on sulfur dioxide:

- SO2 + 2 NaOH → Na2SO3 + H2O

The reverse reaction occurs upon acidification:

- H+ + HSO3− → SO2 + H2O

Reactions

Featuring sulfur in the +4 oxidation state, sulfur dioxide is a reducing agent. It is oxidized by halogens to give the sulfuryl halides, such as sulfuryl chloride:

- SO2 + Cl2 → SO2Cl2

Sulfur dioxide is the oxidising agent in the Claus process, which is conducted on a large scale in oil refineries. Here, sulfur dioxide is reduced by hydrogen sulfide to give elemental sulfur:

- SO2 + 2 H2S → 3 S + 2 H2O

The sequential oxidation of sulfur dioxide followed by its hydration is used in the production of sulfuric acid.

- 2 SO2 + 2 H2O + O2 → 2 H2SO4

Laboratory reactions

Sulfur dioxide is one of the few common acidic yet reducing gases. It turns moist litmus pink (being acidic), then white (due to its bleaching effect). It may be identified by bubbling it through a dichromate solution, turning the solution from orange to green (Cr3+ (aq)). It can also reduce ferric ions to ferrous.[18]

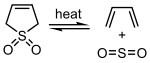

Sulfur dioxide can react with certain 1,3-dienes in a cheletropic reaction to form cyclic sulfones. This reaction is exploited on an industrial scale for the synthesis of sulfolane, which is an important solvent in the petrochemical industry.

Sulfur dioxide can bind to metal ions as a ligand to form metal sulfur dioxide complexes, typically where the transition metal is in oxidation state 0 or +1. Many different bonding modes (geometries) are recognized, but in most cases, the ligand is monodentate, attached to the metal through sulfur, which can be either planar and pyramidal η1.[19] As a η1-SO2 (S-bonded planar) ligand sulfur dioxide functions as a Lewis base using the lone pair on S. SO2 functions as a Lewis acids in its η1-SO2 (S-bonded pyramidal) bonding mode with metals and in its 1:1 adducts with Lewis bases such as dimethylacetamide and trimethyl amine. When bonding to Lewis bases the acid parameters of SO2 are EA = 0.51 and EA = 1.56.

Uses

The overarching, dominant use of sulfur dioxide is in the production of sulfuric acid.[15]

Precursor to sulfuric acid

Sulfur dioxide is an intermediate in the production of sulfuric acid, being converted to sulfur trioxide, and then to oleum, which is made into sulfuric acid. Sulfur dioxide for this purpose is made when sulfur combines with oxygen. The method of converting sulfur dioxide to sulfuric acid is called the contact process. Several billion kilograms are produced annually for this purpose.

Food preservative

Sulfur dioxide is sometimes used as a preservative for dried apricots, dried figs, and other dried fruits, owing to its antimicrobial properties and ability to prevent oxidation,[20] and is called E220[21] when used in this way in Europe. As a preservative, it maintains the colorful appearance of the fruit and prevents rotting. It is also added to sulfured molasses. Sublimed sulfite is ignited and burned in an enclosed space with the fruits. This is usually done outdoors.[22] Fruits may be sulfured by dipping them into an either sodium bisulfite, sodium sulfite or sodium metabisulfite.[22]

Winemaking

Sulfur dioxide was first used in winemaking by the Romans, when they discovered that burning sulfur candles inside empty wine vessels keeps them fresh and free from vinegar smell.[23]

It is still an important compound in winemaking, and is measured in parts per million (ppm) in wine. It is present even in so-called unsulfurated wine at concentrations of up to 10 mg/L.[24] It serves as an antibiotic and antioxidant, protecting wine from spoilage by bacteria and oxidation - a phenomenon that leads to the browning of the wine and a loss of cultivar specific flavors.[25][26] Its antimicrobial action also helps minimize volatile acidity. Wines containing sulfur dioxide are typically labeled with "containing sulfites".

Sulfur dioxide exists in wine in free and bound forms, and the combinations are referred to as total SO2. Binding, for instance to the carbonyl group of acetaldehyde, varies with the wine in question. The free form exists in equilibrium between molecular SO2 (as a dissolved gas) and bisulfite ion, which is in turn in equilibrium with sulfite ion. These equilibria depend on the pH of the wine. Lower pH shifts the equilibrium towards molecular (gaseous) SO2, which is the active form, while at higher pH more SO2 is found in the inactive sulfite and bisulfite forms. The molecular SO2 is active as an antimicrobial and antioxidant, and this is also the form which may be perceived as a pungent odor at high levels. Wines with total SO2 concentrations below 10 ppm do not require "contains sulfites" on the label by US and EU laws. The upper limit of total SO2 allowed in wine in the US is 350 ppm; in the EU it is 160 ppm for red wines and 210 ppm for white and rosé wines. In low concentrations, SO2 is mostly undetectable in wine, but at free SO2 concentrations over 50 ppm, SO2 becomes evident in the smell and taste of wine.

SO2 is also a very important compound in winery sanitation. Wineries and equipment must be kept clean, and because bleach cannot be used in a winery due to the risk of cork taint,[27] a mixture of SO2, water, and citric acid is commonly used to clean and sanitize equipment. Ozone (O3) is now used extensively for sanitizing in wineries due to its efficacy, and because it does not affect the wine or most equipment.[28]

As a reducing agent

Sulfur dioxide is also a good reductant. In the presence of water, sulfur dioxide is able to decolorize substances. Specifically, it is a useful reducing bleach for papers and delicate materials such as clothes. This bleaching effect normally does not last very long. Oxygen in the atmosphere reoxidizes the reduced dyes, restoring the color. In municipal wastewater treatment, sulfur dioxide is used to treat chlorinated wastewater prior to release. Sulfur dioxide reduces free and combined chlorine to chloride.[29]

Sulfur dioxide is fairly soluble in water, and by both IR and Raman spectroscopy; the hypothetical sulfurous acid, H2SO3, is not present to any extent. However, such solutions do show spectra of the hydrogen sulfite ion, HSO3−, by reaction with water, and it is in fact the actual reducing agent present:

- SO2 + H2O ⇌ HSO3− + H+

As a fumigant

In the beginning of the 20th century, sulfur dioxide was used in Buenos Aires as a fumigant to kill rats that carried the Yersinia pestis bacterium, which causes bubonic plague. The application was successful, and the application of this method was extended to other areas in South America. In Buenos Aires, where these apparatuses were known as Sulfurozador, but later also in Rio de Janeiro, New Orleans and San Francisco, the sulfur dioxide treatment machines were brought into the streets to enable extensive disinfection campaigns, with effective results.[30]

Biochemical and biomedical roles

Sulfur dioxide or its conjugate base bisulfite is produced biologically as an intermediate in both sulfate-reducing organisms and in sulfur-oxidizing bacteria, as well. The role of sulfur dioxide in mammalian biology is not yet well understood.[31] Sulfur dioxide blocks nerve signals from the pulmonary stretch receptors and abolishes the Hering–Breuer inflation reflex.

It is considered that endogenous sulfur dioxide plays a significant physiological role in regulating cardiac and blood vessel function, and aberrant or deficient sulfur dioxide metabolism can contribute to several different cardiovascular diseases, such as arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and stenocardia.[32]

It was shown that in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension due to congenital heart diseases the level of homocysteine is higher and the level of endogenous sulfur dioxide is lower than in normal control children. Moreover, these biochemical parameters strongly correlated to the severity of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Authors considered homocysteine to be one of useful biochemical markers of disease severity and sulfur dioxide metabolism to be one of potential therapeutic targets in those patients.[33]

Endogenous sulfur dioxide also has been shown to lower the proliferation rate of endothelial smooth muscle cells in blood vessels, via lowering the MAPK activity and activating adenylyl cyclase and protein kinase A.[34] Smooth muscle cell proliferation is one of important mechanisms of hypertensive remodeling of blood vessels and their stenosis, so it is an important pathogenetic mechanism in arterial hypertension and atherosclerosis.

Endogenous sulfur dioxide in low concentrations causes endothelium-dependent vasodilation. In higher concentrations it causes endothelium-independent vasodilation and has a negative inotropic effect on cardiac output function, thus effectively lowering blood pressure and myocardial oxygen consumption. The vasodilating and bronchodilating effects of sulfur dioxide are mediated via ATP-dependent calcium channels and L-type ("dihydropyridine") calcium channels. Endogenous sulfur dioxide is also a potent antiinflammatory, antioxidant and cytoprotective agent. It lowers blood pressure and slows hypertensive remodeling of blood vessels, especially thickening of their intima. It also regulates lipid metabolism.[35]

Endogenous sulfur dioxide also diminishes myocardial damage, caused by isoproterenol adrenergic hyperstimulation, and strengthens the myocardial antioxidant defense reserve.[36]

As a reagent and solvent in the laboratory

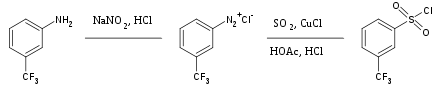

Sulfur dioxide is a versatile inert solvent widely used for dissolving highly oxidizing salts. It is also used occasionally as a source of the sulfonyl group in organic synthesis. Treatment of aryl diazonium salts with sulfur dioxide and cuprous chloride yields the corresponding aryl sulfonyl chloride, for example:[37]

As a result of its very low Lewis basicity, it is often used as a low-temperature solvent/diluent for superacids like magic acid (FSO3H/SbF5), allowing for highly reactive species like tert-butyl cation to be observed spectroscopically at low temperature (though tertiary carbocations do react with SO2 above about –30 °C, and even less reactive solvents like SO2ClF must be used at these higher temperatures).[38]

As a refrigerant

Being easily condensed and possessing a high heat of evaporation, sulfur dioxide is a candidate material for refrigerants. Prior to the development of chlorofluorocarbons, sulfur dioxide was used as a refrigerant in home refrigerators.

Climate engineering

Injections of sulfur dioxide in the stratosphere has been proposed in climate engineering. The cooling effect would be similar to what has been observed after the large explosive 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo. However this form of geoengineering would have uncertain regional consequences on rainfall patterns, for example in monsoon regions.[39]

As an air pollutant

Sulfur dioxide is a noticeable component in the atmosphere, especially following volcanic eruptions.[40] According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),[41] the amount of sulfur dioxide released in the U.S. per year was:

| Year | SO2 |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 31,161,000 short tons (28.3 Mt) |

| 1980 | 25,905,000 short tons (23.5 Mt) |

| 1990 | 23,678,000 short tons (21.5 Mt) |

| 1996 | 18,859,000 short tons (17.1 Mt) |

| 1997 | 19,363,000 short tons (17.6 Mt) |

| 1998 | 19,491,000 short tons (17.7 Mt) |

| 1999 | 18,867,000 short tons (17.1 Mt) |

Sulfur dioxide is a major air pollutant and has significant impacts upon human health.[42] In addition, the concentration of sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere can influence the habitat suitability for plant communities, as well as animal life.[43] Sulfur dioxide emissions are a precursor to acid rain and atmospheric particulates. Due largely to the US EPA's Acid Rain Program, the U.S. has had a 33% decrease in emissions between 1983 and 2002. This improvement resulted in part from flue-gas desulfurization, a technology that enables SO2 to be chemically bound in power plants burning sulfur-containing coal or oil. In particular, calcium oxide (lime) reacts with sulfur dioxide to form calcium sulfite:

- CaO + SO2 → CaSO3

Aerobic oxidation of the CaSO3 gives CaSO4, anhydrite. Most gypsum sold in Europe comes from flue-gas desulfurization.

To control sulfur emissions, dozens of methods with relatively high efficiencies have been developed for fitting of coal-fired power plants.[44]

Sulfur can be removed from coal during burning by using limestone as a bed material in fluidized bed combustion.[45]

Sulfur can also be removed from fuels before burning, preventing formation of SO2 when the fuel is burnt. The Claus process is used in refineries to produce sulfur as a byproduct. The Stretford process has also been used to remove sulfur from fuel. Redox processes using iron oxides can also be used, for example, Lo-Cat[46] or Sulferox.[47]

An analysis found that 18 coal-fired power stations in the western Balkans emitted two-and-half times more sulphur dioxide than all 221 coal plants in the EU combined.[48]

Fuel additives such as calcium additives and magnesium carboxylate may be used in marine engines to lower the emission of sulfur dioxide gases into the atmosphere.[49]

As of 2006, China was the world's largest sulfur dioxide polluter, with 2005 emissions estimated to be 25,490,000 short tons (23.1 Mt). This amount represents a 27% increase since 2000, and is roughly comparable with U.S. emissions in 1980.[50]

A sulfur dioxide plume from Halemaʻumaʻu, which glows at night

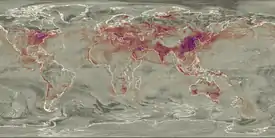

A sulfur dioxide plume from Halemaʻumaʻu, which glows at night Sulfur dioxide in the world on April 15, 2017. Note that sulfur dioxide moves through the atmosphere with prevailing winds and thus local sulfur dioxide distributions vary day to day with weather patterns and seasonality.

Sulfur dioxide in the world on April 15, 2017. Note that sulfur dioxide moves through the atmosphere with prevailing winds and thus local sulfur dioxide distributions vary day to day with weather patterns and seasonality.

Safety

Inhalation

Incidental exposure to sulfur dioxide is routine, e.g. the smoke from matches, coal, and sulfur-containing fuels.

Sulfur dioxide is mildly toxic and can be hazardous in high concentrations.[51] Long-term exposure to low concentrations is also problematic. A 2011 systematic review concluded that exposure to sulfur dioxide is associated with preterm birth.[52]

U.S. regulations

In 2008, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists reduced the short-term exposure limit to 0.25 parts per million (ppm). In the US, the OSHA set the PEL at 5 ppm (13 mg/m3) time-weighted average. Also in the US, NIOSH set the IDLH at 100 ppm.[53] In 2010, the EPA "revised the primary SO2 NAAQS by establishing a new one-hour standard at a level of 75 parts per billion (ppb). EPA revoked the two existing primary standards because they would not provide additional public health protection given a one-hour standard at 75 ppb."[42]

Ingestion

In the United States, the Center for Science in the Public Interest lists the two food preservatives, sulfur dioxide and sodium bisulfite, as being safe for human consumption except for certain asthmatic individuals who may be sensitive to them, especially in large amounts.[54] Symptoms of sensitivity to sulfiting agents, including sulfur dioxide, manifest as potentially life-threatening trouble breathing within minutes of ingestion.[55] Sulphites may also cause symptoms in non-asthmatic individuals, namely dermatitis, urticaria, flushing, hypotension, abdominal pain and diarrhea, and even life-threatening anaphylaxis.[56]

See also

- Bunker fuel

- National Ambient Air Quality Standards

- Sulfur trioxide

- Sulfur–iodine cycle

References

- Sulfur dioxide Archived 2019-12-30 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- Miller, J.W. Jr.; Shah, P.N.; Yaws, C.L. (1976). "Correlation constants for chemical compounds". Chemical Engineering. 83 (25): 153–180. ISSN 0009-2460.

- "C&L Inventory".

- "Sulfur dioxide". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0575". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Cunningham, Terence P.; Cooper, David L.; Gerratt, Joseph; Karadakov, Peter B. & Raimondi, Mario (1997). "Chemical bonding in oxofluorides of hypercoordinatesulfur". Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions. 93 (13): 2247–2254. doi:10.1039/A700708F.

- Owen, Lewis A.; Pickering, Kevin T (1997). An Introduction to Global Environmental Issues. Taylor copper extraction& Francis. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-203-97400-1.

- Taylor, J.A.; Simpson, R.W.; Jakeman, A.J. (1987). "A hybrid model for predicting the distribution of sulphur dioxide concentrations observed near elevated point sources". Ecological Modelling. 36 (3–4): 269–296. doi:10.1016/0304-3800(87)90071-8. ISSN 0304-3800.

- Marcq, Emmanuel; Bertaux, Jean-Loup; Montmessin, Franck; Belyaev, Denis (2012). "Variations of sulphur dioxide at the cloud top of Venus's dynamic atmosphere". Nature Geoscience. 6 (1): 25–28. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6...25M. doi:10.1038/ngeo1650. ISSN 1752-0894. S2CID 59323909.

- Halevy, I.; Zuber, M. T.; Schrag, D. P. (2007). "A Sulfur Dioxide Climate Feedback on Early Mars". Science. 318 (5858): 1903–1907. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1903H. doi:10.1126/science.1147039. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18096802. S2CID 7246517.

- Lellouch, E.; et al. (2007). "Io's atmosphere". In Lopes, R. M. C.; Spencer, J. R. (eds.). Io after Galileo. Springer-Praxis. pp. 231–264. ISBN 978-3-540-34681-4.

- Cruikshank, D. P.; Howell, R. R.; Geballe, T. R.; Fanale, F. P. (1985). "Sulfur Dioxide Ice on IO". ICES in the Solar System. pp. 805–815. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-5418-2_55. ISBN 978-94-010-8891-6.

- Europa's Hidden Ice Chemistry – NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Jpl.nasa.gov (2010-10-04). Retrieved on 2013-09-24.

- Müller, Hermann. "Sulfur Dioxide". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a25_569.

- Shriver, Atkins. Inorganic Chemistry, Fifth Edition. W. H. Freeman and Company; New York, 2010; p. 414.

- WHITEHAVEN COAST ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY. lakestay.co.uk (2007)

- "Information archivée dans le Web" (PDF).

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Zamboni, Cibele B.; Medeiros, Ilca M. M. A.; de Medeiros, José A. G. (October 2011). Analysis of Sulfur in Dried Fruits Using NAA (PDF). 2011 International Nuclear Atlantic Conference - INAC 2011. ISBN 978-85-99141-03-8.

- Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers, The Food Standards Agency website.

- Preserving foods: Drying fruits and Vegetable (PDF), University of Georgia cooperative extension service

- "Practical Winery & vineyard Journal Jan/Feb 2009". www.practicalwinery.com. 1 Feb 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-09-28.

- Sulphites in wine, MoreThanOrganic.com.

- Jackson, R.S. (2008) Wine science: principles and applications, Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press

- Guerrero, Raúl F; Cantos-Villar, Emma (2015). "Demonstrating the efficiency of sulphur dioxide replacements in wine: A parameter review". Trends in Food Science & Technology. 42: 27–43. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2014.11.004.

- Chlorine Use in the Winery. Purdue University

- Use of ozone for winery and environmental sanitation, Practical Winery & Vineyard Journal.

- Tchobanoglous, George (1979). Wastewater Engineering (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-041677-X.

- Engelmann, Lukas (July 2018). "Fumigating the Hygienic Model City: Bubonic Plague and the Sulfurozador in Early-Twentieth-Century Buenos Aires". Medical History. 62 (3): 360–382. doi:10.1017/mdh.2018.37. PMC 6113751. PMID 29886876.

- Liu, D.; Jin, H.; Tang, C.; Du, J. (2010). "Sulfur Dioxide: a Novel Gaseous Signal in the Regulation of Cardiovascular Functions". Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 10 (11): 1039–1045. doi:10.2174/1389557511009011039. PMID 20540708.

- Tian, Hong (5 November 2014). "Advances in the study on endogenous sulfur dioxide in the cardiovascular system". Chinese Medical Journal. 127 (21): 3803–3807. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20133031 (inactive 31 July 2022). PMID 25382339.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022 (link) - Yang R, Yang Y, Dong X, Wu X, Wei Y (Aug 2014). "Correlation between endogenous sulfur dioxide and homocysteine in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease". Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi (in Chinese). 52 (8): 625–629. PMID 25224243.

- Liu D, Huang Y, Bu D, Liu AD, Holmberg L, Jia Y, Tang C, Du J, Jin H (May 2014). "Sulfur dioxide inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via suppressing the Erk/MAP kinase pathway mediated by cAMP/PKA signaling". Cell Death Dis. 5 (5): e1251. doi:10.1038/cddis.2014.229. PMC 4047873. PMID 24853429.

- Wang XB, Jin HF, Tang CS, Du JB (16 Nov 2011). "The biological effect of endogenous sulfur dioxide in the cardiovascular system". Eur J Pharmacol. 670 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.031. PMID 21925165.

- Liang Y, Liu D, Ochs T, Tang C, Chen S, Zhang S, Geng B, Jin H, Du J (Jan 2011). "Endogenous sulfur dioxide protects against isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury and increases myocardial antioxidant capacity in rats". Lab. Invest. 91 (1): 12–23. doi:10.1038/labinvest.2010.156. PMID 20733562.

- Hoffman, R. V. (1990). "m-Trifluoromethylbenzenesulfonyl Chloride". Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, vol. 7, p. 508

- Olah, George A.; Lukas, Joachim. (1967-08-01). "Stable carbonium ions. XLVII. Alkylcarbonium ion formation from alkanes via hydride (alkide) ion abstraction in fluorosulfonic acid-antimony pentafluoride-sulfuryl chlorofluoride solution". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 89 (18): 4739–4744. doi:10.1021/ja00994a030. ISSN 0002-7863.

- Clarke L., K. Jiang, K. Akimoto, M. Babiker, G. Blanford, K. Fisher-Vanden, J.-C. Hourcade, V. Krey, E. Kriegler, A. Löschel, D. McCollum, S. Paltsev, S. Rose, P. R. Shukla, M. Tavoni, B. C. C. van der Zwaan, and D.P. van Vuuren, 2014: Assessing Transformation Pathways. In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Zwickel and J.C. Minx (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- Volcanic Gases and Their Effects. Volcanoes.usgs.gov. Retrieved on 2011-10-31.

- National Trends in Sulfur Dioxide Levels, United States Environmental Protection Agency.

- Sulfur Dioxide (SO2) Pollution. United States Environmental Protection Agency

- Hogan, C. Michael (2010). "Abiotic factor" in Encyclopedia of Earth. Emily Monosson and C. Cleveland (eds.). National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- Lin, Cheng-Kuan; Lin, Ro-Ting; Chen, Pi-Cheng; Wang, Pu; De Marcellis-Warin, Nathalie; Zigler, Corwin; Christiani, David C. (2018-02-08). "A Global Perspective on Sulfur Oxide Controls in Coal-Fired Power Plants and Cardiovascular Disease". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 2611. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.2611L. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-20404-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5805744. PMID 29422539.

- Lindeburg, Michael R. (2006). Mechanical Engineering Reference Manual for the PE Exam. Belmont, C.A.: Professional Publications, Inc. pp. 27–3. ISBN 978-1-59126-049-3.

- FAQ’s About Sulfur Removal and Recovery using the LO-CAT® Hydrogen Sulfide Removal System. gtp-merichem.com

- Process screening analysis of alternative gas treating and sulfur removal for gasification. (December 2002) Report by SFA Pacific, Inc. prepared for U.S. Department of Energy (PDF) . Retrieved on 2011-10-31.

- Carrington, Damian (2021-09-06). "More global aid goes to fossil fuel projects than tackling dirty air – study". The Guardian. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - May, Walter R. Marine Emissions Abatement Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine. SFA International, Inc., p. 6.

- China has its worst spell of acid rain, United Press International (2006-09-22).

- Sulfur Dioxide Basics U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Shah PS, Balkhair T, Knowledge Synthesis Group on Determinants of Preterm/LBW Births (2011). "Air pollution and birth outcomes: a systematic review". Environ Int. 37 (2): 498–516. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2010.10.009. PMID 21112090.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards".

- "Center for Science in the Public Interest – Chemical Cuisine". Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "California Department of Public Health: Food and Drug Branch: Sulfites" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- Vally H, Misso NL (2012). "Adverse reactions to the sulphite additives". Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 5 (1): 16–23. PMC 4017440. PMID 24834193.

External links

- Global map of sulfur dioxide distribution

- United States Environmental Protection Agency Sulfur Dioxide page

- International Chemical Safety Card 0074

- IARC Monographs. "Sulfur Dioxide and some Sulfites, Bisulfites and Metabisulfites". vol. 54. 1992. p. 131.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- CDC – Sulfure Dioxide – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic

- Sulfur Dioxide, Molecule of the Month