Pakistani architecture

Pakistani architecture is intertwined with the architecture of the broader Indian subcontinent. With the beginning of the Indus civilization around the middle of the 3rd millennium BC,[1] for the first time in the area which encompasses today's Pakistan an advanced urban culture developed with large structural facilities, some of which survive to this day. This was followed by the Gandhara style of Buddhist architecture that borrowed elements from Ancient Greece. These remnants are visible in the Gandhara capital of Taxila.[2]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Traditions |

| Folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Sport |

|

Indo-Islamic architecture emerged during the medieval period, which combined Indian and Persianaite elements. The Mughal Empire ruled between the 16th and 18th centuries, and saw the rise of Mughal architecture, most prevalent in Lahore.

During the British Colonial period, European styles such as the Baroque, Gothic and Neoclassical became prevalent. The British, like the Mughals, built elaborate buildings to project their power. The Indo-Saracenic style, a fusion of British and Indo-Islamic elements also developed. After Independence, modern architectural styles like the International style became popular.

Harappan architecture

Archaeologists excavated numerous Bronze Age cities, among them are Mohenjo Daro, Harrappa and Kot Diji from the 3rd millennium BCE. They have a uniform, appropriate structure with broad roads as well as well thought out sanitary and drainage facilities. The majority of the discovered brick constructions are public buildings such as bath houses and workshops. Wood and loam served as construction materials. Large scale temples, such as those found in other ancient cities are missing. With the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization the architecture also suffered considerable damage.[3]

Little is known about this civilization, often called Harappan, partly because it disappeared about 1700 BC for reasons unknown, its language remains undeciphered, its existence was revealed only in the 1920s, and excavations have been limited. Surviving evidences indicate a sophisticated civilization. Cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro (the "City of the Dead") had populations of some 35,000, they were laid out according to a grid system. Inhabitants lived in windowless baked brick houses built around a central courtyard. These cities also had a citadel, where the public and religious buildings were located, large pools for ritual bathing, granaries for the storage of food, and a complex system of covered drains and sewers. The latter rivaled the engineering skill of the Romans some 2,000 years later.

Gandharan architecture

During classical antiquity, a special Gandharan architecture evolved in the ancient region of Gandhara with the rise of Buddhism.[1] In addition, the Persian and Greek influence led to the development of the Greco-Buddhist style, starting from the 1st century AD. The high point of this era was reached with the culmination of the Gandhara style.

Important remnants of Buddhist construction are stupas and other buildings with clearly recognizable Greek statues and style elements like support columns which, beside ruins from other epochs, are found in the Gandhara capital Taxila[6] in the extreme north of the Punjab. A particularly beautiful example of Buddhist architecture is the ruins of the Buddhist monastery Takht-i-Bahi in the northwest province.[7]

Takht-i-Bahi complex

Takht-i-Bahi complex Jaulian, an example of Gandharan architecture

Jaulian, an example of Gandharan architecture Dharmarajika Stupa in Taxila

Dharmarajika Stupa in Taxila

Hindu temple architecture

During Pre Islamic era in Pakistan, there was a prominent population of Hindus, especially in provinces in Punjab and Sindh. The important temples built during that era include:

The Shri Katas Raj Temples (Punjabi, Urdu: شری کٹاس راج مندر) also known as Qila Katas (قلعہ کٹاس),[8] is a complex of several Hindu temples connected to one another by walkways.[8] The temple complex surrounds a pond named Katas which is regarded as sacred by Hindus.[9] The complex is located in the Potohar Plateau region of Pakistan's Punjab province.

The Amb Temples (Urdu: امب مندر) are part of a Hindu temple complex located at the western edge of the Salt Range in Pakistan's Punjab province. The temple complex was built in the 7th to 9th centuries CE during the reign of the Hindu Shahi empire.[10] The main temple is roughly 15 to 20 metres tall, and has three stories, with stairwells leading to inner ambulatories.

The Shri Varun Dev Mandir and Sharada Peeth are other examples of Hindu temple architecture in Pakistan.

Temples at Katas Raj display characteristics of Kashmiri Hindu temples

Temples at Katas Raj display characteristics of Kashmiri Hindu temples Katas Raj Temples (4th century) in Pakistan

Katas Raj Temples (4th century) in Pakistan One of the Amb Temples constructed between the 7th and 9th centuries

One of the Amb Temples constructed between the 7th and 9th centuries

Jain architecture

The Nagarparkar Jain Temples (Urdu: نگرپارکر جین مندر) are located in the region around Nagarparkar, in Pakistan's southern Sindh province. The site consists of a collection of Jain temples. They were built in Māru-Gurjara style in 12th century AD to the 15th century - a period when Jain architectural expression was at its zenith.[11] The temples were inscribed on the tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage status in 2016 as the Nagarparkar Cultural Landscape.[11]

Viravah temple, one of Jain temples at Nagarparkar

Viravah temple, one of Jain temples at Nagarparkar Frescoes at Gori temple of the Nagarparkar Jain Temples

Frescoes at Gori temple of the Nagarparkar Jain Temples One of ancient Jain temples at Nagarparkar

One of ancient Jain temples at Nagarparkar

Indo-Islamic architecture

Early Era (8th century to 16th century)

The arrival of Islam in today's Pakistan - first in Sindh - during the 8th century CE meant a sudden end of Buddhist architecture. However, a smooth transition to predominantly pictureless Islamic architecture occurred.[12]

The earliest example of a mosque from the days of infancy of Islam in South Asia is the Mihrablose mosque of Banbhore, from the year 727, the first Muslim place of worship in South Asia. Under the Delhi Sultan, the Persian-centralasiatic style ascended over Arab influences. The most important characteristic of this style is the Iwan, walled on three sides, with one end entirely open. Further characteristics are wide prayer halls, round domes with mosaics and geometrical samples and the use of painted tiles. The most important of the few completely discovered buildings of Islamic architecture is the tomb of the Shah Rukn-i-Alam (built 1320 to 1324) in Multan.[13]

The Makli Necropolis at Thatta, which includes tombs of various rulers, noblemen and Sufi saints of Sindh was built between the 14th and 18th centuries. It showcases a wide variety of architecture, including Indo-Islamic, Persian, Hindu and Rajput and Gujarati influences.[14] The Chaukhandi Tombs near Karachi are similar in style.[15]

Other examples include the Rohtas Fort built by Sher Shah Suri in the 16th century,[12] and the Tombs of the Talpur Mirs.

Mughal Architecture (16th–18th centuries CE)

Mughal architecture emerged in the medieval period during the reign of the Mughal Empire in the 15th to 17th centuries. Mughal buildings have a uniform pattern of structure and character, including large bulbous domes, slender minarets at the corners, massive halls, large vaulted gateways and delicate ornamentation, usually surrounded by gardens on all four sides.

The buildings are usually constructed out of red sandstone and white marble, and make use of decorative work such as pachin kari and jali-latticed screens.

The earliest example in Pakistan is the Lahore Fort, which had existed at least since the 11th century but was completely rebuilt by various Mughal Emperors like Akbar and Jahangir (1556–1627) .[16] The Tomb of Anarkali, Hiran Minar and Begum Shahi Mosque also date back to this period.

The Tomb of Jahangir, the fourth Mughal Emperor, was completed in 1637 during the reign of his son and successor Shah Jahan. The Emperor had forbidden the construction of a dome over his tomb, and thus the roof is simple and free of any embellishments. It stands amidst a garden which also houses the Tomb of Nur Jahan, Tomb of Asif Khan and Akbari Sarai, the one of the most well-preserved caravanserais in Pakistan.[17]

Mughal architecture reached its zenith in the 17th century during the reign of Shah Jahan.[18][16] During this time, several additions were made to the Lahore Fort. Other masterpieces of this time include the Wazir Khan Mosque, Dai Anga Mosque, Tomb of Dai Anga, Shalimar Gardens and Shahi Hammam in Lahore.[19][20] The Shah Jahan Mosque in Thatta reflects a heavy Persian influence.[21]

The Badshahi Mosque in Lahore was built during the reign of Aurangzeb in 1673. It is made out of red sandstone with three marble domes, very similar to the Jama Masjid of Delhi. It remains one of the largest mosques in the world.[22]

Naulakha pavilion (1633) in the Lahore Fort[16]

Naulakha pavilion (1633) in the Lahore Fort[16]

The Wazir Khan Mosque[20]

The Wazir Khan Mosque[20] Shalimar Gardens, Lahore[16]

Shalimar Gardens, Lahore[16] Akbari Sarai[17]

Akbari Sarai[17]

Regional architecture

Architecture of Sindh

Architecture of province of Sindh is greatly influenced from its neighbouring regions of Gujarat and Punjab, as well as broader Indo-Islamic architecture. The necropolis at Makli gives a good example of Sindhi architecture. Its architecture of the largest monuments synthesizes Muslim, Hindu, Persian, Mughal, and Gujarati influences,[23] in the style of Lower Sindh that became known as the Chaukhandi style, named after the Chaukhandi tombs near Karachi. The Chaukhandi style came to incorporate slabs of sandstone that were carefully carved by stonemasons into intricate and elaborate designs.[24]

By the 15th century, decorated rosettes and circular patterns began to be incorporated into the tombs. More complex patterns and Arabic calligraphy with biographical information of the interred body then emerged. Larger monuments dating from later periods included corridors and some designs inspired by cosmology.[24] Pyramidal structures from the 16th century feature the use of minarets topped with floral motifs in a style unique to tombs dating from the Turkic Trakhan dynasty. Structures from the 17th century at the Leilo Sheikh part of the cemetery feature large tombs that resemble Jain temples from afar,[24] with prominent influence from the nearby region of Gujarat.

Several of the larger tombs feature carvings of animals, warriors, and weaponry – a practice uncommon to Muslim funerary monuments. Later tombs at the site are sometimes made entirely of brick, with only a sandstone slab.[25] The largest structures in the most archetypal Chaukhandi style feature domed yellow sandstone canopies that were plastered white with wooden doorways, in a style that reflects Central Asian and Persian influences. The size of the dome denoted the prominence of the buried individual, with undersides embellished with carved floral patterns.[24] The underside of some canopies feature lotus flowers, a symbol commonly associated with Hinduism.[26]

They also feature extensive blue tile-work typical of Sindh.[24] The use of funerary pavilions eventually expanded beyond lower Sindh, and influenced funerary architecture in neighbouring Gujarat.[27] The Chaukhandi tombs are embellished with geometrical designs and motifs, including figural representations such as mounted horsemen, hunting scenes, arms, and jewelry.

Apart from tombs, Ranikot Fort and Kot Diji Fort are also a good example of Sindhi architecture.

Kot Diji Fort in Sindh

Kot Diji Fort in Sindh Interior of one of the Talpur tombs

Interior of one of the Talpur tombs Canopy tomb of Daya Khan Rahu

Canopy tomb of Daya Khan Rahu View of Tomb of Jam Mubarak Khan

View of Tomb of Jam Mubarak Khan The Shah Jahan mosque's main dome has tiles arranged in a stellate pattern to represent the night sky

The Shah Jahan mosque's main dome has tiles arranged in a stellate pattern to represent the night sky Makli Necropolis features several monumental tombs dating from the 14th to 18th centuries

Makli Necropolis features several monumental tombs dating from the 14th to 18th centuries

Architecture of Multan

A distinct Multani style of architecture began taking root in the 14th century with the establishment of funerary monuments,[28] and is characterized by large brick walls reinforced by wooden anchors, with inward sloping roofs.[28] Funerary architecture is also reflected in the city's residential quarters, which borrow architectural and decorative elements from Multan's mausolea.[28]

In spite of being in Punjab, the architecture of city of Multan is more influenced by the architecture of the neighbouring province of Sindh. It is usually expressed in the form of mausoleums of Sufi saints.

Rajput architecture

The Rajput architecture makes an extensive use of Jalis, Chatris and Jharokhas. All these features also have influenced Mughal architecture. The forts of Derawar and Umerkot were built by Rajput clans during the medieval era, and are examples of early Rajput architecture.

Sikh architecture

Sikh architecture is a style of architecture that was developed under Sikh Empire during 18th and 19th century in the Punjab region. Named after Sikhism, a religion native to Punjab, Sikh Architecture is heavily influenced by Mughal architecture and Islamic styles. The onion dome, frescoes, in-lay work, and multi-foil arches, are Mughal influences, more specially from Shah Jahan's period, whereas chattris, oriel windows, bracket supported eaves at the string-course, and ornamented friezes are derived from elements of Rajput architecture.

One of the most well known examples of Sikh architecture is the Samadhi of Ranjit Singh, built in 1839. The building has gilded fluted domes and cupolas, and an ornate balustrade around the upper portion of the building. The dome is decorated with Naga (serpent) hood designs - the product of Hindu craftsmen that worked on the project.[29] The wooden panels on the ceiling are decorated with stained glass work, while the walls are richly decorated with floral designs. The ceilings are decorated with glass mosaic work.

Gurdwara Dera Sahib and Gurdwara Panja Sahib are other prominent examples.

Darbar Sahib, gurdwara commemorating Guru Nanak, in Kartarpur, Pakistan

Darbar Sahib, gurdwara commemorating Guru Nanak, in Kartarpur, Pakistan Golden dome of Gurdwara Dera Sahib in Lahore

Golden dome of Gurdwara Dera Sahib in Lahore Samadhi of Ranjit Singh in Lahore, an example of Sikh architecture in Pakistan

Samadhi of Ranjit Singh in Lahore, an example of Sikh architecture in Pakistan

Indo-Saracenic architecture

During the British Raj, European architectural styles such as baroque, gothic and neoclassical became more predominant. The Frere Hall, St. Patrick's Cathedral and Mereweather Clock Tower in Karachi, and neoclassical Montgomery Hall in Lahore are some examples.

A new style of architecture known as Indo-Saracenic revival style developed, from a mixture of European and Indo-Islamic components. Among the more prominent works are seen in the cities of Karachi (Mohatta Palace, Karachi Metropolitan Corporation Building), in Peshawar (Islamia College University) and Lahore (Lahore Museum, University of the Punjab and King Edward Medical University).

Karachi Metropolitan Corporation Building, Karachi

Karachi Metropolitan Corporation Building, Karachi University of the Punjab, Lahore

University of the Punjab, Lahore The present building of the Lahore Museum was designed by Sir Ganga Ram and completed in 1894

The present building of the Lahore Museum was designed by Sir Ganga Ram and completed in 1894

Post-Independence

After Independence, the architecture of Pakistan is a blend of historic Islamic and various modern styles.

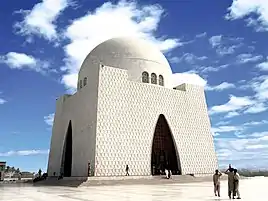

This reflects itself, particularly in modern structures. In addition, buildings of monumental importance such as the Minar-e-Pakistan in Lahore or the mausoleum established with white marble known as Mazar-e-Quaid for the founder of the state expressed the self-confidence of the nascent state.

The city of Islamabad was designed by Greek architect Constantinos Apostolou Doxiadis and completed in 1966. The Faisal Mosque in Islamabad, one of the largest mosques in the world, is one of the best examples of modern Islamic architecture. It was designed by Vedat Dalokay and constructed between 1976 and 1986.

The National Monument in Islamabad, built in 2007 is in the shape of a blooming flower. The four main petals of the monument represent the four provinces of Balochistan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Sindh, while the three smaller petals represent the three territories of Gilgit-Baltistan, Azad Kashmir and the Tribal Areas.[lower-alpha 1]

Skyscrapers built in the international style are becoming more prevalent in the cities.

World Heritage Sites

There are currently six sites in Pakistan listed under the UNESCO World Heritage:

- Archaeological Ruins at Moenjodaro

- Buddhist Ruins at Takht-i-Bahi and Neighbouring City Remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol

- Lahore Fort and Shalimar Gardens (Lahore)

- Historic Monuments of Thatta

- Rohtas Fort

- Taxila

Gallery

Mughal

Moti Masjid located within the Lahore Fort

Moti Masjid located within the Lahore Fort Tomb of Jahangir

Tomb of Jahangir Mahabat Khan Mosque, Peshawar

Mahabat Khan Mosque, Peshawar Shah Jahan Mosque in Thatta

Shah Jahan Mosque in Thatta.jpg.webp) Oonchi Mosque in Lahore

Oonchi Mosque in Lahore A Mughal era monument - Chauburji in Lahore

A Mughal era monument - Chauburji in Lahore

Indo-Saracenic

Mohatta Palace in Karachi

Mohatta Palace in Karachi Sadiq Dane High School, Bahawalpur

Sadiq Dane High School, Bahawalpur Patiala Block of King Edward Medical University, Lahore

Patiala Block of King Edward Medical University, Lahore Noor Mahal, Bahawalpur

Noor Mahal, Bahawalpur Karachi Chamber of Commerce Building

Karachi Chamber of Commerce Building Darbar Mahal, Bahawalpur

Darbar Mahal, Bahawalpur Multan Clock Tower, Multan

Multan Clock Tower, Multan National Academy of Performing Arts, Karachi

National Academy of Performing Arts, Karachi Frere Hall, Karachi

Frere Hall, Karachi

Post-Independence

Minar-e-Pakistan at Lahore

Minar-e-Pakistan at Lahore

_Clifton%252C_Karachi.jpg.webp) Teen Talwar, Karachi

Teen Talwar, Karachi Pakistan Monument, Islamabad

Pakistan Monument, Islamabad

See also

- Culture of Pakistan

- List of Pakistani architects

- List of mosques in Pakistan

References

Notes

- Tribal Areas were merged into Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa in 2018.

Citations

- Guisepi, R.A. The Indus Valley And The Genesis Of South Asian Civilization[Usurped!]. Retrieved on February 6, 2008

- Meister, M.W. (1997). Gandhara-Nagara Temples of the Salt Range and the Indus. Kala, the Journal of Indian Art History Congress. Vol 4 (1997-98), pp. 45-52.

- Meister, M.W. (1996). Temples Along the Indus Archived 2006-05-27 at the Wayback Machine. Expedition, the Magazine of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Vol 38, Issue 3. pp. 41-54

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Archaeological Ruins at Moenjodaro". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Archaeological Site of Harappa". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Taxila". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Neighbouring City Remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Khalid, Laiba (January 2015). "Katas Raj Temples" (PDF). Explore Rural India. Vol. 3, no. 1. The Indian Trust for Rural Heritage and Development. pp. 55–57. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- Sah, Krishna Kumar (2016). Deva Bhumi: The Abode of the Gods in India. BookBaby. p. 79. ISBN 9780990631491. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- Gazetteer of the Attock District, 1930, Part 1. Sang-e-Meel Publications. 1932. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- "Tentative Lists". UNESCO. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Rohtas Fort". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Tomb of Shah Rukn-e-Alam". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Historical Monuments at Makli, Thatta". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Chaukhandi Tombs, Karachi". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Fort and Shalamar Gardens in Lahore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Tombs of Jahangir, Asif Khan and Akbari Sarai, Lahore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Simon Ross Valentine. 'Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at: History, Belief, Practice Hurst Publishers, 2008 ISBN 1850659168 p 63

- "Wazir Khan Mosque - Google Arts & Culture". Google Cultural Institute. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Wazir Khan's Mosque, Lahore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Shah Jahan Mosque, Thatta". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Badshahi Mosque, Lahore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- "Historical Monuments at Makli, Thatta". UNESCO. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Malik, Iftikhar (2006). Culture and Customs of Pakistan. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313331268. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- "Makli Hill". ArchNet. Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Qureshi, Urooj (8 August 2014). "In Pakistan, imposing tombs that few have seen". BBC Travel. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Hasan, Shaikh Khurshid (2001). The Islamic Architectural Heritage of Pakistan: Funerary Memorial Architecture. Royal Book Company. ISBN 978-9694072623. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Bignami, Daniele Fabrizio; Del Bo, Adalberto (2014). Sustainable Social, Economic and Environmental Revitalization in Multan City: A Multidisciplinary Italian–Pakistani Project. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783319021171.

- Samadhi of Ranjit Singh – a sight of religious harmony, Pakistan Today. JANUARY 16, 2016, NADEEM DAR

Further reading

- Mumtaz, Kamil Khan. Architecture in Pakistan Singapore: Concept Media Pte Ltd, 1985.

- Maurizio, Taddei and De Marco, Giuseppe. "Chronology of Temples in the Salt Range, Pakistan". South Asian Archaeology. Rome: Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, 2000.

- "Crossing Lines, Architecture in Early Islamic South Asia". Anthropology and Aesthetics 43 (2003)

- "Malot and the Originality of the Punjab". Punjab Journal of Archaeology and History 1 (1997)

- "Pattan Munara: Minar or Mandir?". Hari Smiriti: Studies in Art, Archaeology and Indology, Papers Presented in Memory of Dr. H. Sarkar, New Delhi: Kaveri Books, 2006.

External links

- ARTSEDGE Pakistan: The Gift of the Indus

- Pakistan's Salt Range Temples - A photographic review of Professor Michael W. Meister of the University of Pennsylvania.

- Architecture in Pakistan: A Historical Overview

- Islamic Architecture Pakistan

- Modernity and Tradition: Contemporary Architecture in Pakistan

- 100+1 Pakistani Architects And Their Own Houses - Amazon.com Accessed May 4, 2008

- Islamic Architecture in South Asia: Pakistan-India-Bangladesh

- The Architectural Heritage of Bahawalpur