Cyprus

Cyprus[lower-alpha 6] (/ˈsaɪprəs/ (![]() listen)), officially the Republic of Cyprus,[lower-alpha 7] is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. It is situated south of the Anatolian Peninsula, and its continental position is disputed, with it often being considered a part of both Western Asia and Southeast Europe. Cyprus is the third-largest and third-most populous island in the Mediterranean,[13][14] and is located south of Turkey, east of Greece, Egypt to the south and west of Syria. Its capital and largest city is Nicosia.

listen)), officially the Republic of Cyprus,[lower-alpha 7] is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. It is situated south of the Anatolian Peninsula, and its continental position is disputed, with it often being considered a part of both Western Asia and Southeast Europe. Cyprus is the third-largest and third-most populous island in the Mediterranean,[13][14] and is located south of Turkey, east of Greece, Egypt to the south and west of Syria. Its capital and largest city is Nicosia.

Republic of Cyprus | |

|---|---|

Flag

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms

| |

| Anthem: Ὕμνος εἰς τὴν Ἐλευθερίαν[lower-alpha 1] "Hymn to Liberty" | |

Location of Cyprus (pictured lower right), showing the Republic of Cyprus in darker green and disputed territory shown in brighter green, with the rest of the European Union shown in faded green | |

| Capital and largest city | Nicosia 35°10′N 33°22′E |

| Official languages | |

| Minority languages |

|

| Vernaculars |

|

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion (2020; including Northern Cyprus) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Cypriot |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Nicos Anastasiades |

• Vice-President | Vacant[lower-alpha 2] |

• President of the House of Representatives | Annita Demetriou |

| Legislature | House of Representatives |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

• London-Zürich Agreements | 19 February 1959 |

• Independence proclaimed | 16 August 1960 |

• Independence Day | 1 October 1960 |

• Joined the EU | 1 May 2004 |

| Area | |

• Total[lower-alpha 3] | 9,251 km2 (3,572 sq mi) (162nd) |

• Water (%) | 0.11[5] |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 1,244,188[lower-alpha 3][6][7] (158th) |

• 2011 census | 838,897[lower-alpha 4][8] |

• Density | 123.4[lower-alpha 3][9]/km2 (319.6/sq mi) (82nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 29th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| UTC+3 (EEST) | |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +357 |

| ISO 3166 code | CY |

| Internet TLD | .cy[lower-alpha 5] |

The earliest known human activity on the island dates to around the 10th millennium BC. Archaeological remains include the well-preserved ruins from the Hellenistic period such as Salamis and Kourion, and Cyprus is home to some of the oldest water wells in the world.[15] Cyprus was settled by Mycenaean Greeks in two waves in the 2nd millennium BC. As a strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean, it was subsequently occupied by several major powers, including the empires of the Assyrians, Egyptians and Persians, from whom the island was seized in 333 BC by Alexander the Great. Subsequent rule by Ptolemaic Egypt, the Classical and Eastern Roman Empire, Arab caliphates for a short period, the French Lusignan dynasty and the Venetians was followed by over three centuries of Ottoman rule between 1571 and 1878 (de jure until 1914).[16]

Cyprus is a major tourist destination in the Mediterranean.[17][18][19] With an advanced,[20] high-income economy and a very high Human Development Index,[21][22] the Republic of Cyprus has been a member of the Commonwealth since 1961 and was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement until it joined the European Union on 1 May 2004.[23] On 1 January 2008, the Republic of Cyprus joined the eurozone.[24]

Etymology

The earliest attested reference to Cyprus is the 15th century BC Mycenaean Greek 𐀓𐀠𐀪𐀍, ku-pi-ri-jo,[25] meaning "Cypriot" (Greek: Κύπριος), written in Linear B syllabic script.[26] The classical Greek form of the name is Κύπρος (Kýpros).

The etymology of the name is unknown. Suggestions include:

- the Greek word for the Mediterranean cypress tree (Cupressus sempervirens), κυπάρισσος (kypárissos)

- the Greek name of the henna tree (Lawsonia alba), κύπρος (kýpros)

- an Eteocypriot word for copper. It has been suggested, for example, that it has roots in the Sumerian word for copper (zubar) or for bronze (kubar), from the large deposits of copper ore found on the island.[27]

Through overseas trade, the island has given its name to the Classical Latin word for copper through the phrase aes Cyprium, "metal of Cyprus", later shortened to Cuprum.[27][28]

The standard demonym relating to Cyprus or its people or culture is Cypriot. The terms Cypriote and Cyprian (later a personal name) are also used, though less frequently.

The state's official name in Greek literally translates to "Cypriot Republic" in English, but this translation is not used officially; "Republic of Cyprus" is used instead.

History

Prehistoric and Ancient Cyprus

The earliest confirmed site of human activity on Cyprus is Aetokremnos, situated on the south coast, indicating that hunter-gatherers were active on the island from around 10,000 BC,[29] with settled village communities dating from 8200 BC. The arrival of the first humans correlates with the extinction of the 75 cm high Cyprus dwarf hippopotamus and 1 metre tall Cyprus dwarf elephant, the only large mammals native to the island.[30] Water wells discovered by archaeologists in western Cyprus are believed to be among the oldest in the world, dated at 9,000 to 10,500 years old.[15]

Remains of an 8-month-old cat were discovered buried with a human body at a separate Neolithic site in Cyprus.[31] The grave is estimated to be 9,500 years old (7500 BC), predating ancient Egyptian civilisation and pushing back the earliest known feline-human association significantly.[32] The remarkably well-preserved Neolithic village of Khirokitia is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, dating to approximately 6800 BC.[33]

During the Late Bronze Age, the island experienced two waves of Greek settlement.[34] The first wave consisted of Mycenaean Greek traders, who started visiting Cyprus around 1400 BC.[35][36][37] A major wave of Greek settlement is believed to have taken place following the Late Bronze Age collapse of Mycenaean Greece from 1100 to 1050 BC, with the island's predominantly Greek character dating from this period.[37][38] The first recorded name of a Cypriot king is Kushmeshusha, as appears on letters sent to Ugarit in the 13th century BCE.[39] Cyprus occupies an important role in Greek mythology, being the birthplace of Aphrodite and Adonis, and home to King Cinyras, Teucer and Pygmalion.[40] Literary evidence suggests an early Phoenician presence at Kition, which was under Tyrian rule at the beginning of the 10th century BC.[41] Some Phoenician merchants who were believed to come from Tyre colonised the area and expanded the political influence of Kition. After c. 850 BC, the sanctuaries [at the Kathari site] were rebuilt and reused by the Phoenicians.

Cyprus is at a strategic location in the Middle East.[42][43][44] It was ruled by the Neo-Assyrian Empire for a century starting in 708 BC, before a brief spell under Egyptian rule and eventually Achaemenid rule in 545 BC.[37] The Cypriots, led by Onesilus, king of Salamis, joined their fellow Greeks in the Ionian cities during the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt in 499 BC against the Achaemenids. The revolt was suppressed, but Cyprus managed to maintain a high degree of autonomy and remained inclined towards the Greek world.[37] During the whole period of the Persian rule, there is a continuity in the reign of the Cypriot kings and during their rebellions they were crushed by Persian rulers from Asia Minor, which is an indication that the Cypriots were ruling the island with directly regulated relations with the Great King and there wasn't a Persian satrap.[45] The Kingdoms of Cyprus enjoyed special privileges and a semi-autonomous status, but they were still considered vassal subjects of the Great King.[45]

The island was conquered by Alexander the Great in 333 BC and Cypriot navy helped Alexander during the Siege of Tyre (332 BC). Cypriot fleet were also sent to help Amphoterus (admiral).[46] In addition, Alexander had two Cypriot generals Stasander and Stasanor both from the Soli and later both became satraps in Alexander's empire. Following Alexander's death, the division of his empire, and the subsequent Wars of the Diadochi, Cyprus became part of the Hellenistic empire of Ptolemaic Egypt. It was during this period that the island was fully Hellenized. In 58 BC Cyprus was acquired by the Roman Republic.[37]

Middle Ages

When the Roman Empire was divided into Eastern and Western parts in 286, Cyprus became part of the East Roman Empire (also called the Byzantine Empire), and would remain so for some 900 years. Under Byzantine rule, the Greek orientation that had been prominent since antiquity developed the strong Hellenistic-Christian character that continues to be a hallmark of the Greek Cypriot community.[47]

Beginning in 649, Cyprus endured several attacks launched by raiders from the Levant, which continued for the next 300 years. Many were quick piratical raids, but others were large-scale attacks in which many Cypriots were slaughtered and great wealth carried off or destroyed.[47] There are no Byzantine churches which survive from this period; thousands of people were killed, and many cities – such as Salamis – were destroyed and never rebuilt.[37] Byzantine rule was restored in 965, when Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas scored decisive victories on land and sea.[37]

In 1156 Raynald of Châtillon and Thoros II of Armenia brutally sacked Cyprus over a period of three weeks, stealing so much plunder and capturing so many of the leading citizens and their families for ransom, that the island took generations to recover. Several Greek priests were mutilated and sent away to Constantinople.[48]

In 1185 Isaac Komnenos, a member of the Byzantine imperial family, took over Cyprus and declared it independent of the Empire. In 1191, during the Third Crusade, Richard I of England captured the island from Isaac.[49] He used it as a major supply base that was relatively safe from the Saracens. A year later Richard sold the island to the Knights Templar, who, following a bloody revolt, in turn sold it to Guy of Lusignan. His brother and successor Aimery was recognised as King of Cyprus by Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor.[37]

Following the death in 1473 of James II, the last Lusignan king, the Republic of Venice assumed control of the island, while the late king's Venetian widow, Queen Catherine Cornaro, reigned as figurehead. Venice formally annexed the Kingdom of Cyprus in 1489, following the abdication of Catherine.[37] The Venetians fortified Nicosia by building the Walls of Nicosia, and used it as an important commercial hub. Throughout Venetian rule, the Ottoman Empire frequently raided Cyprus. In 1539 the Ottomans destroyed Limassol and so fearing the worst, the Venetians also fortified Famagusta and Kyrenia.[37]

Although the Lusignan French aristocracy remained the dominant social class in Cyprus throughout the medieval period, the former assumption that Greeks were treated only as serfs on the island[37] is no longer considered by academics to be accurate. It is now accepted that the medieval period saw increasing numbers of Greek Cypriots elevated to the upper classes, a growing Greek middle ranks,[50] and the Lusignan royal household even marrying Greeks. This included King John II of Cyprus who married Helena Palaiologina.[51]

Cyprus under the Ottoman Empire

In 1570, a full-scale Ottoman assault with 60,000 troops brought the island under Ottoman control, despite stiff resistance by the inhabitants of Nicosia and Famagusta. Ottoman forces capturing Cyprus massacred many Greek and Armenian Christian inhabitants.[52] The previous Latin elite were destroyed and the first significant demographic change since antiquity took place with the formation of a Muslim community.[53] Soldiers who fought in the conquest settled on the island and Turkish peasants and craftsmen were brought to the island from Anatolia.[54] This new community also included banished Anatolian tribes, "undesirable" persons and members of various "troublesome" Muslim sects, as well as a number of new converts on the island.[55]

The Ottomans abolished the feudal system previously in place and applied the millet system to Cyprus, under which non-Muslim peoples were governed by their own religious authorities. In a reversal from the days of Latin rule, the head of the Church of Cyprus was invested as leader of the Greek Cypriot population and acted as mediator between Christian Greek Cypriots and the Ottoman authorities. This status ensured that the Church of Cyprus was in a position to end the constant encroachments of the Roman Catholic Church.[56] Ottoman rule of Cyprus was at times indifferent, at times oppressive, depending on the temperaments of the sultans and local officials, and the island began over 250 years of economic decline.[57]

The ratio of Muslims to Christians fluctuated throughout the period of Ottoman domination. In 1777–78, 47,000 Muslims constituted a majority over the island's 37,000 Christians.[58] By 1872, the population of the island had risen to 144,000, comprising 44,000 Muslims and 100,000 Christians.[59] The Muslim population included numerous crypto-Christians,[60] including the Linobambaki, a crypto-Catholic community that arose due to religious persecution of the Catholic community by the Ottoman authorities;[60][61] this community would assimilate into the Turkish Cypriot community during British rule.[62]

As soon as the Greek War of Independence broke out in 1821, several Greek Cypriots left for Greece to join the Greek forces. In response, the Ottoman governor of Cyprus arrested and executed 486 prominent Greek Cypriots, including the Archbishop of Cyprus, Kyprianos, and four other bishops.[63] In 1828, modern Greece's first president Ioannis Kapodistrias called for union of Cyprus with Greece, and numerous minor uprisings took place.[64] Reaction to Ottoman misrule led to uprisings by both Greek and Turkish Cypriots, although none were successful. After centuries of neglect by the Ottoman Empire, the poverty of most of the people and the ever-present tax collectors fuelled Greek nationalism, and by the 20th century the idea of enosis, or union, with newly independent Greece was firmly rooted among Greek Cypriots.[57]

Under Ottoman rule, numeracy, school enrolment and literacy rates were all low. They persisted some time after Ottoman rule ended, and then increased rapidly during the twentieth century.[65]

Cyprus under the British Empire

In the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) and the Congress of Berlin, Cyprus was leased to the British Empire which de facto took over its administration in 1878 (though, in terms of sovereignty, Cyprus remained a de jure Ottoman territory until 5 November 1914, together with Egypt and Sudan)[16] in exchange for guarantees that Britain would use the island as a base to protect the Ottoman Empire against possible Russian aggression.[37]

The island would serve Britain as a key military base for its colonial routes. By 1906, when the Famagusta harbour was completed, Cyprus was a strategic naval outpost overlooking the Suez Canal, the crucial main route to India which was then Britain's most important overseas possession. Following the outbreak of the First World War and the decision of the Ottoman Empire to join the war on the side of the Central Powers, on 5 November 1914 the British Empire formally annexed Cyprus and declared the Ottoman Khedivate of Egypt and Sudan a Sultanate and British protectorate.[16][37]

In 1915, Britain offered Cyprus to Greece, ruled by King Constantine I of Greece, on condition that Greece join the war on the side of the British. The offer was declined. In 1923, under the Treaty of Lausanne, the nascent Turkish republic relinquished any claim to Cyprus,[66] and in 1925 it was declared a British crown colony.[37] During the Second World War, many Greek and Turkish Cypriots enlisted in the Cyprus Regiment.

The Greek Cypriot population, meanwhile, had become hopeful that the British administration would lead to enosis. The idea of enosis was historically part of the Megali Idea, a greater political ambition of a Greek state encompassing the territories with Greek inhabitants in the former Ottoman Empire, including Cyprus and Asia Minor with a capital in Constantinople, and was actively pursued by the Cypriot Orthodox Church, which had its members educated in Greece. These religious officials, together with Greek military officers and professionals, some of whom still pursued the Megali Idea, would later found the guerrilla organisation Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston or National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA).[67][68] The Greek Cypriots viewed the island as historically Greek and believed that union with Greece was a natural right.[69] In the 1950s, the pursuit of enosis became a part of the Greek national policy.[70]

Initially, the Turkish Cypriots favoured the continuation of the British rule.[71] However, they were alarmed by the Greek Cypriot calls for enosis, as they saw the union of Crete with Greece, which led to the exodus of Cretan Turks, as a precedent to be avoided,[72][73] and they took a pro-partition stance in response to the militant activity of EOKA.[74] The Turkish Cypriots also viewed themselves as a distinct ethnic group of the island and believed in their having a separate right to self-determination from Greek Cypriots.[69] Meanwhile, in the 1950s, Turkish leader Menderes considered Cyprus an "extension of Anatolia", rejected the partition of Cyprus along ethnic lines and favoured the annexation of the whole island to Turkey. Nationalistic slogans centred on the idea that "Cyprus is Turkish" and the ruling party declared Cyprus to be a part of the Turkish homeland that was vital to its security. Upon realising that the fact that the Turkish Cypriot population was only 20% of the islanders made annexation unfeasible, the national policy was changed to favour partition. The slogan "Partition or Death" was frequently used in Turkish Cypriot and Turkish protests starting in the late 1950s and continuing throughout the 1960s. Although after the Zürich and London conferences Turkey seemed to accept the existence of the Cypriot state and to distance itself from its policy of favouring the partition of the island, the goal of the Turkish and Turkish Cypriot leaders remained that of creating an independent Turkish state in the northern part of the island.[75][76]

In January 1950, the Church of Cyprus organised a referendum under the supervision of clerics and with no Turkish Cypriot participation,[77] where 96% of the participating Greek Cypriots voted in favour of enosis,[78][79][80]: 9 The Greeks were 80.2% of the total island' s population at the time (census 1946). Restricted autonomy under a constitution was proposed by the British administration but eventually rejected. In 1955 the EOKA organisation was founded, seeking union with Greece through armed struggle. At the same time the Turkish Resistance Organisation (TMT), calling for Taksim, or partition, was established by the Turkish Cypriots as a counterweight.[81] British officials also tolerated the creation of the Turkish underground organisation T.M.T. The Secretary of State for the Colonies in a letter dated 15 July 1958 had advised the Governor of Cyprus not to act against T.M.T despite its illegal actions so as not to harm British relations with the Turkish government.[76]

Independence and inter-communal violence

When Cyprus was placed under the United Kingdom's administration based on the Cyprus Convention in 1878 and was formally annexed by the UK in 1914. The future of the island became a matter of disagreement between the two prominent ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots, who made up 77% of the population in 1960, and Turkish Cypriots, who made up 18% of the population. From the 19th century onwards, the Greek Cypriot population pursued enosis, union with Greece, which became a Greek national policy in the 1950s.[82][83] The Turkish Cypriot population initially advocated the continuation of the British rule, then demanded the annexation of the island to Turkey, and in the 1950s, together with Turkey, established a policy of taksim, the partition of Cyprus and the creation of a Turkish polity in the north.[84]

On 16 August 1960, Cyprus attained independence after the Zürich and London Agreement between the United Kingdom, Greece and Turkey. Cyprus had a total population of 573,566; of whom 442,138 (77.1%) were Greeks, 104,320 (18.2%) Turks, and 27,108 (4.7%) others.[85] The UK retained the two Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, while government posts and public offices were allocated by ethnic quotas, giving the minority Turkish Cypriots a permanent veto, 30% in parliament and administration, and granting the three mother-states guarantor rights.

However, the division of power as foreseen by the constitution soon resulted in legal impasses and discontent on both sides, and nationalist militants started training again, with the military support of Greece and Turkey respectively. The Greek Cypriot leadership believed that the rights given to Turkish Cypriots under the 1960 constitution were too extensive and designed the Akritas plan, which was aimed at reforming the constitution in favour of Greek Cypriots, persuading the international community about the correctness of the changes and violently subjugating Turkish Cypriots in a few days should they not accept the plan.[86] Tensions were heightened when Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios III called for constitutional changes, which were rejected by Turkey[80]: 17–20 and opposed by Turkish Cypriots.[86]

Intercommunal violence erupted on 21 December 1963, when two Turkish Cypriots were killed at an incident involving the Greek Cypriot police. The violence resulted in the death of 364 Turkish and 174 Greek Cypriots,[87] destruction of 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages and displacement of 25,000–30,000 Turkish Cypriots. The crisis resulted in the end of the Turkish Cypriot involvement in the administration and their claiming that it had lost its legitimacy;[80]: 56–59 the nature of this event is still controversial. In some areas, Greek Cypriots prevented Turkish Cypriots from travelling and entering government buildings, while some Turkish Cypriots willingly withdrew due to the calls of the Turkish Cypriot administration.[88] Turkish Cypriots started living in enclaves. The republic's structure was changed, unilaterally, by Makarios, and Nicosia was divided by the Green Line, with the deployment of UNFICYP troops.[80]: 56–59

In 1964, Turkey threatened to invade Cyprus[89] in response to the continuing Cypriot intercommunal violence, but this was stopped by a strongly worded telegram from the US President Lyndon B. Johnson on 5 June, warning that the US would not stand beside Turkey in case of a consequential Soviet invasion of Turkish territory.[90] Meanwhile, by 1964, enosis was a Greek policy and would not be abandoned; Makarios and the Greek prime minister Georgios Papandreou agreed that enosis should be the ultimate aim and King Constantine wished Cyprus "a speedy union with the mother country". Greece dispatched 10,000 troops to Cyprus to counter a possible Turkish invasion.[91]

Following nationalist violence in the 1950s, Cyprus was granted independence in 1960.[92] The crisis of 1963–64 brought further intercommunal violence between the two communities, displaced more than 25,000 Turkish Cypriots into enclaves[80]: 56–59 [93] and brought the end of Turkish Cypriot representation in the republic. On 15 July 1974, a coup d'état was staged by Greek Cypriot nationalists[94][95] and elements of the Greek military junta[96] in an attempt at enosis. This action precipitated the Turkish invasion of Cyprus on 20 July,[97] which led to the capture of the present-day territory of Northern Cyprus and the displacement of over 150,000 Greek Cypriots[98][99] and 50,000 Turkish Cypriots.[100] A separate Turkish Cypriot state in the north was established by unilateral declaration in 1983; the move was widely condemned by the international community, with Turkey alone recognising the new state. These events and the resulting political situation are matters of a continuing dispute.

1974 coup d'état, invasion, and division

On 15 July 1974, the Greek military junta under Dimitrios Ioannides carried out a coup d'état in Cyprus, to unite the island with Greece.[101][102][103] The coup ousted president Makarios III and replaced him with pro-enosis nationalist Nikos Sampson.[104] In response to the coup,[lower-alpha 8] five days later, on 20 July 1974, the Turkish army invaded the island, citing a right to intervene to restore the constitutional order from the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee. This justification has been rejected by the United Nations and the international community.[110]

The Turkish air force began bombing Greek positions in Cyprus, and hundreds of paratroopers were dropped in the area between Nicosia and Kyrenia, where well-armed Turkish Cypriot enclaves had been long-established; while off the Kyrenia coast, Turkish troop ships landed 6,000 men as well as tanks, trucks and armoured vehicles.[111][112]

Three days later, when a ceasefire had been agreed,[113] Turkey had landed 30,000 troops on the island and captured Kyrenia, the corridor linking Kyrenia to Nicosia, and the Turkish Cypriot quarter of Nicosia itself.[113] The junta in Athens, and then the Sampson regime in Cyprus fell from power. In Nicosia, Glafkos Clerides temporarily assumed the presidency.[113] But after the peace negotiations in Geneva, the Turkish government reinforced their Kyrenia bridgehead and started a second invasion on 14 August.[114] The invasion resulted in Morphou, Karpass, Famagusta and the Mesaoria coming under Turkish control.

International pressure led to a ceasefire, and by then 36% of the island had been taken over by the Turks and 180,000 Greek Cypriots had been evicted from their homes in the north.[115] At the same time, around 50,000 Turkish Cypriots were displaced to the north and settled in the properties of the displaced Greek Cypriots. Among a variety of sanctions against Turkey, in mid-1975 the US Congress imposed an arms embargo on Turkey for using US-supplied equipment during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974.[116] There were 1,534 Greek Cypriots[117] and 502 Turkish Cypriots[118] missing as a result of the fighting from 1963 to 1974.

The Republic of Cyprus has de jure sovereignty over the entire island, including its territorial waters and exclusive economic zone, with the exception of the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, which remain under the UK's control according to the London and Zürich Agreements. However, the Republic of Cyprus is de facto partitioned into two main parts: the area under the effective control of the Republic, located in the south and west and comprising about 59% of the island's area, and the north,[119] administered by the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, covering about 36% of the island's area. Another nearly 4% of the island's area is covered by the UN buffer zone. The international community considers the northern part of the island to be territory of the Republic of Cyprus occupied by Turkish forces.[lower-alpha 9] The occupation is viewed as illegal under international law and amounting to illegal occupation of EU territory since Cyprus became a member of the European Union.[125]

Post-division

After the restoration of constitutional order and the return of Archbishop Makarios III to Cyprus in December 1974, Turkish troops remained, occupying the northeastern portion of the island. In 1983, the Turkish Cypriot parliament, led by the Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktaş, proclaimed the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which is recognised only by Turkey.[4]

The events of the summer of 1974 dominate the politics on the island, as well as Greco-Turkish relations. Turkish settlers have been settled in the north with the encouragement of the Turkish and Turkish Cypriot states. The Republic of Cyprus considers their presence a violation of the Geneva Convention,[80]: 56–59 whilst many Turkish settlers have since severed their ties to Turkey and their second generation considers Cyprus to be their homeland.[126]

.jpg.webp)

The Turkish invasion, the ensuing occupation and the declaration of independence by the TRNC have been condemned by United Nations resolutions, which are reaffirmed by the Security Council every year.[127] Attempts to resolve the Cyprus dispute have continued. In 2004, the Annan Plan, drafted by the UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, was put to a referendum in both Northern Cyprus and the Cypriot Republic. 65% of Turkish Cypriots voted in support of the plan and 74% Greek Cypriots voted against the plan, claiming that it disproportionately favoured the Turkish side.[128] In total, 66.7% of the voters rejected the Annan Plan.

On 1 May 2004 Cyprus joined the European Union, together with nine other countries.[129] Cyprus was accepted into the EU as a whole, although the EU legislation is suspended in Northern Cyprus until a final settlement of the Cyprus problem.

Efforts have been made to enhance freedom of movement between the two sides. In April 2003, Northern Cyprus unilaterally eased border restrictions, permitting Cypriots to cross between the two sides for the first time in 30 years.[130] In March 2008, a wall that had stood for decades at the boundary between the Republic of Cyprus and the UN buffer zone was demolished.[131] The wall had cut across Ledra Street in the heart of Nicosia and was seen as a strong symbol of the island's 32-year division. On 3 April 2008, Ledra Street was reopened in the presence of Greek and Turkish Cypriot officials.[132] North and South relaunched reunification talks in 2015,[133] but these collapsed in 2017.[134]

The European Union issued a warning in February 2019 that Cyprus, an EU member, was selling EU passports to Russian oligarchs, saying it would allow organised crime syndicates to infiltrate the EU.[135] In 2020 leaked documents revealed a wider range of former and current officials from Afghanistan, China, Dubai, Lebanon, the Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Ukraine and Vietnam who bought a Cypriot citizenship prior to a change of the law in July 2019.[136][137] Cyprus and Turkey have been engaged in a dispute over the extent of their exclusive economic zones, ostensibly sparked by oil and gas exploration in the area.[138]

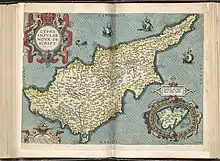

Geography

Cyprus is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after the Italian islands of Sicily and Sardinia[4] (both in terms of area and population). It is also the world's 80th largest by area and world's 51st largest by population. It measures 240 kilometres (149 mi) long from end to end and 100 kilometres (62 mi) wide at its widest point, with Turkey 75 kilometres (47 mi) to the north. It lies between latitudes 34° and 36° N, and longitudes 32° and 35° E.

Other neighboring territories include Syria and Lebanon to the east and southeast (105 and 108 kilometres (65 and 67 mi), respectively), Israel 200 kilometres (124 mi) to the southeast, The Gaza Strip 427 kilometres (265 mi) to the southeast, Egypt 380 kilometres (236 mi) to the south, and Greece to the northwest: 280 kilometres (174 mi) to the small Dodecanesian island of Kastellorizo (Megisti), 400 kilometres (249 mi) to Rhodes and 800 kilometres (497 mi) to the Greek mainland. Sources alternatively place Cyprus in Europe,[139][140][141] or Western Asia and the Middle East.[142][143]

The physical relief of the island is dominated by two mountain ranges, the Troodos Mountains and the smaller Kyrenia Range, and the central plain they encompass, the Mesaoria. The Mesaoria plain is drained by the Pedieos River, the longest on the island. The Troodos Mountains cover most of the southern and western portions of the island and account for roughly half its area. The highest point on Cyprus is Mount Olympus at 1,952 m (6,404 ft), located in the centre of the Troodos range. The narrow Kyrenia Range, extending along the northern coastline, occupies substantially less area, and elevations are lower, reaching a maximum of 1,024 m (3,360 ft). The island lies within the Anatolian Plate.[144]

Cyprus contains the Cyprus Mediterranean forests ecoregion.[145] It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.06/10, ranking it 59th globally out of 172 countries.[146]

Geopolitically, the island is subdivided into four main segments. The Republic of Cyprus occupies the southern two-thirds of the island (59.74%). The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus occupies the northern third (34.85%), and the United Nations-controlled Green Line provides a buffer zone that separates the two and covers 2.67% of the island. Lastly, two bases under British sovereignty are located on the island: Akrotiri and Dhekelia, covering the remaining 2.74%.

Climate

Cyprus has a subtropical climate – Mediterranean and semi-arid type (in the north-eastern part of the island) – Köppen climate classifications Csa and BSh,[147][148] with very mild winters (on the coast) and warm to hot summers. Snow is possible only in the Troodos Mountains in the central part of island. Rain occurs mainly in winter, with summer being generally dry.

Cyprus has one of the warmest climates in the Mediterranean part of the European Union. The average annual temperature on the coast is around 24 °C (75 °F) during the day and 14 °C (57 °F) at night. Generally, summers last about eight months, beginning in April with average temperatures of 21–23 °C (70–73 °F) during the day and 11–13 °C (52–55 °F) at night, and ending in November with average temperatures of 22–23 °C (72–73 °F) during the day and 12–14 °C (54–57 °F) at night, although in the remaining four months temperatures sometimes exceed 20 °C (68 °F).[149]

Among all cities in the Mediterranean part of the European Union, Limassol has one of the warmest winters, in the period January – February average temperature is 17–18 °C (63–64 °F) during the day and 7–8 °C (45–46 °F) at night, in other coastal locations in Cyprus is generally 16–17 °C (61–63 °F) during the day and 6–8 °C (43–46 °F) at night. During March, Limassol has average temperatures of 19–20 °C (66–68 °F) during the day and 9–11 °C (48–52 °F) at night, in other coastal locations in Cyprus is generally 17–19 °C (63–66 °F) during the day and 8–10 °C (46–50 °F) at night.[149]

The middle of summer is hot – in July and August on the coast the average temperature is usually around 33 °C (91 °F) during the day and around 22 °C (72 °F) at night (inland, in the highlands average temperature exceeds 35 °C (95 °F)) while in the June and September on the coast the average temperature is usually around 30 °C (86 °F) during the day and around 20 °C (68 °F) at night in Limassol, while is usually around 28 °C (82 °F) during the day and around 18 °C (64 °F) at night in Paphos. Large fluctuations in temperature are rare. Inland temperatures are more extreme, with colder winters and hotter summers compared with the coast of the island.[149]

Average annual temperature of sea is 21–22 °C (70–72 °F), from 17 °C (63 °F) in February to 27–28 °C (81–82 °F) in August (depending on the location). In total 7 months – from May to November – the average sea temperature exceeds 20 °C (68 °F).[150]

Sunshine hours on the coast are around 3,200 per year, from an average of 5–6 hours of sunshine per day in December to an average of 12–13 hours in July.[150] This is about double that of cities in the northern half of Europe; for comparison, London receives about 1,540 per year.[151] In December, London receives about 50 hours of sunshine[151] while coastal locations in Cyprus about 180 hours (almost as much as in May in London).

Water supply

Cyprus suffers from a chronic shortage of water. The country relies heavily on rain to provide household water, but in the past 30 years average yearly precipitation has decreased.[152] Between 2001 and 2004, exceptionally heavy annual rainfall pushed water reserves up, with supply exceeding demand, allowing total storage in the island's reservoirs to rise to an all-time high by the start of 2005. However, since then demand has increased annually – a result of local population growth, foreigners moving to Cyprus and the number of visiting tourists – while supply has fallen as a result of more frequent droughts.[152]

Dams remain the principal source of water both for domestic and agricultural use; Cyprus has a total of 107 dams (plus one currently under construction) and reservoirs, with a total water storage capacity of about 330,000,000 m3 (1.2×1010 cu ft).[153] Water desalination plants are gradually being constructed to deal with recent years of prolonged drought.

The Government has invested heavily in the creation of water desalination plants which have supplied almost 50 per cent of domestic water since 2001. Efforts have also been made to raise public awareness of the situation and to encourage domestic water users to take more responsibility for the conservation of this increasingly scarce commodity.

Turkey has built a water pipeline under the Mediterranean Sea from Anamur on its southern coast to the northern coast of Cyprus, to supply Northern Cyprus with potable and irrigation water (see Northern Cyprus Water Supply Project).

Politics

Cyprus is a presidential republic. The head of state and of the government is elected by a process of universal suffrage for a five-year term. Executive power is exercised by the government with legislative power vested in the House of Representatives whilst the Judiciary is independent of both the executive and the legislature.

The 1960 Constitution provided for a presidential system of government with independent executive, legislative and judicial branches as well as a complex system of checks and balances including a weighted power-sharing ratio designed to protect the interests of the Turkish Cypriots. The executive was led by a Greek Cypriot president and a Turkish Cypriot vice-president elected by their respective communities for five-year terms and each possessing a right of veto over certain types of legislation and executive decisions. Legislative power rested on the House of Representatives who were also elected on the basis of separate voters' rolls.

Since 1965, following clashes between the two communities, the Turkish Cypriot seats in the House remain vacant. In 1974 Cyprus was divided de facto when the Turkish army occupied the northern third of the island. The Turkish Cypriots subsequently declared independence in 1983 as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus but were recognised only by Turkey. In 1985 the TRNC adopted a constitution and held its first elections. The United Nations recognises the sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus over the entire island of Cyprus.

The House of Representatives currently has 59 members elected for a five-year term, 56 members by proportional representation and three observer members representing the Armenian, Latin and Maronite minorities. 24 seats are allocated to the Turkish community but remain vacant since 1964. The political environment is dominated by the communist AKEL, the liberal conservative Democratic Rally, the centrist[154] Democratic Party, the social-democratic EDEK and the centrist EURO.KO. In 2008, Dimitris Christofias became the country's first Communist head of state. Due to his involvement in the 2012–13 Cypriot financial crisis, Christofias did not run for re-election in 2013. The Presidential election in 2013 resulted in Democratic Rally candidate Nicos Anastasiades winning 57.48% of the vote. As a result, Anastasiades was sworn in on and has been president since 28 February 2013. Anastasiades was re-elected with 56% of the vote in the 2018 presidential election.[155][156]

Administrative divisions

The Republic of Cyprus is divided into six districts: Nicosia, Famagusta, Kyrenia, Larnaca, Limassol and Paphos.[157]

Exclaves and enclaves

Cyprus has four exclaves, all in territory that belongs to the British Sovereign Base Area of Dhekelia. The first two are the villages of Ormidhia and Xylotymvou. The third is the Dhekelia Power Station, which is divided by a British road into two parts. The northern part is the EAC refugee settlement. The southern part, even though located by the sea, is also an exclave because it has no territorial waters of its own, those being UK waters.[158]

The UN buffer zone runs up against Dhekelia and picks up again from its east side off Ayios Nikolaos and is connected to the rest of Dhekelia by a thin land corridor. In that sense the buffer zone turns the Paralimni area on the southeast corner of the island into a de facto, though not de jure, exclave.

Foreign relations

The Republic of Cyprus is a member of the following international groups: Australia Group, CN, CE, CFSP, EBRD, EIB, EU, FAO, IAEA, IBRD, ICAO, ICC, ICCt, ITUC, IDA, IFAD, IFC, IHO, ILO, IMF, IMO, Interpol, IOC, IOM, IPU, ITU, MIGA, NAM, NSG, OPCW, OSCE, PCA, UN, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNHCR, UNIDO, UPU, WCL, WCO, WFTU, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WToO, WTO.[4][159]

Armed forces

The Cypriot National Guard is the main military institution of the Republic of Cyprus. It is a combined arms force, with land, air and naval elements. Historically all men were required to spend 24 months serving in the National Guard after their 17th birthday, but in 2016 this period of compulsory service was reduced to 14 months.[160]

Annually, approximately 10,000 persons are trained in recruit centres. Depending on their awarded speciality the conscript recruits are then transferred to speciality training camps or to operational units.

While until 2016 the armed forces were mainly conscript based, since then a large Professional Enlisted institution has been adopted (ΣΥΟΠ), which combined with the reduction of conscript service produces an approximate 3:1 ratio between conscript and professional enlisted.

Law, justice and human rights

The Cyprus Police (Greek: Αστυνομία Κύπρου, Turkish: Kıbrıs Polisi) is the only National Police Service of the Republic of Cyprus and is under the Ministry of Justice and Public Order since 1993.[161]

In "Freedom in the World 2011", Freedom House rated Cyprus as "free".[162] In January 2011, the Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the question of Human Rights in Cyprus noted that the ongoing division of Cyprus continues to affect human rights throughout the island "including freedom of movement, human rights pertaining to the question of missing persons, discrimination, the right to life, freedom of religion, and economic, social and cultural rights".[163] The constant focus on the division of the island can sometimes mask other human rights issues.

In 2014, Turkey was ordered by the European Court of Human Rights to pay well over $100m in compensation to Cyprus for the invasion;[164] Ankara announced that it would ignore the judgment.[165] In 2014, a group of Cypriot refugees and a European parliamentarian, later joined by the Cypriot government, filed a complaint to the International Court of Justice, accusing Turkey of violating the Geneva Conventions by directly or indirectly transferring its civilian population into occupied territory. Other violations of the Geneva and the Hague Conventions—both ratified by Turkey—amount to what archaeologist Sophocles Hadjisavvas called "the organized destruction of Greek and Christian heritage in the north".[166] These violations include looting of cultural treasures, deliberate destruction of churches, neglect of works of art, and altering the names of important historical sites, which was condemned by the International Council on Monuments and Sites. Hadjisavvas has asserted that these actions are motivated by a Turkish policy of erasing the Greek presence in Northern Cyprus within a framework of ethnic cleansing. But some perpetrators are just motivated by greed and are seeking profit.[166] Art law expert Alessandro Chechi has classified the connection of cultural heritage destruction to ethnic cleansing as the "Greek Cypriot viewpoint", which he reports as having been dismissed by two PACE reports. Chechi asserts joint Greek and Turkish Cypriot responsibility for the destruction of cultural heritage in Cyprus, noting the destruction of Turkish Cypriot heritage in the hands of Greek Cypriot extremists.[167]

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

In the early 21st century the Cypriot economy has diversified and become prosperous.[168] However, in 2012 it became affected by the Eurozone financial and banking crisis. In June 2012, the Cypriot government announced it would need €1.8 billion in foreign aid to support the Cyprus Popular Bank, and this was followed by Fitch downgrading Cyprus's credit rating to junk status.[169] Fitch said Cyprus would need an additional €4 billion to support its banks and the downgrade was mainly due to the exposure of Bank of Cyprus, Cyprus Popular Bank and Hellenic Bank, Cyprus's three largest banks, to the Greek financial crisis.[169]

The 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis led to an agreement with the Eurogroup in March 2013 to split the country's second largest bank, the Cyprus Popular Bank (also known as Laiki Bank), into a "bad" bank which would be wound down over time and a "good" bank which would be absorbed by the Bank of Cyprus. In return for a €10 billion bailout from the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund, often referred to as the "troika", the Cypriot government was required to impose a significant haircut on uninsured deposits, a large proportion of which were held by wealthy Russians who used Cyprus as a tax haven. Insured deposits of €100,000 or less were not affected.[170][171][172]

According to the 2017 International Monetary Fund estimates, its per capita GDP (adjusted for purchasing power) at $36,442 is below the average of the European Union.[173][174] Cyprus has been sought as a base for several offshore businesses for its low tax rates. Tourism, financial services and shipping are significant parts of the economy. Economic policy of the Cyprus government has focused on meeting the criteria for admission to the European Union. The Cypriot government adopted the euro as the national currency on 1 January 2008.[168]

Cyprus is the last EU member fully isolated from energy interconnections and it is expected that it will be connected to European network via EuroAsia Interconnector, 2000 MW HVDC undersea power cable.[175] EuroAsia Interconnector will connect Greek, Cypriot, and Israeli power grids. It is a leading Project of Common Interest of the European Union and also priority Electricity Highway Interconnector Project.[176][177]

In recent years significant quantities of offshore natural gas have been discovered in the area known as Aphrodite (at the exploratory drilling block 12) in Cyprus's exclusive economic zone (EEZ),[178] about 175 kilometres (109 miles) south of Limassol at 33°5'40″N and 32°59'0″E.[179] However, Turkey's offshore drilling companies have accessed both natural gas and oil resources since 2013.[180] Cyprus demarcated its maritime border with Egypt in 2003, with Lebanon in 2007,[181] and with Israel in 2010.[182] In August 2011, the US-based firm Noble Energy entered into a production-sharing agreement with the Cypriot government regarding the block's commercial development.[183]

Turkey, which does not recognise the border agreements of Cyprus with its neighbours,[184] threatened to mobilise its naval forces if Cyprus proceeded with plans to begin drilling at Block 12.[185] Cyprus's drilling efforts have the support of the US, EU, and UN, and on 19 September 2011 drilling in Block 12 began without any incidents being reported.[186]

Because of the heavy influx of tourists and foreign investors, the property rental market in Cyprus has grown in recent years.[187] In late 2013, the Cyprus Town Planning Department announced a series of incentives to stimulate the property market and increase the number of property developments in the country's town centres.[188] This followed earlier measures to quickly give immigration permits to third country nationals investing in Cyprus property.[189]

Transport

Available modes of transport are by road, sea and air. Of the 10,663 km (6,626 mi) of roads in the Republic of Cyprus in 1998, 6,249 km (3,883 mi) were paved, and 4,414 km (2,743 mi) were unpaved. In 1996 the Turkish-occupied area had a similar ratio of paved to unpaved, with approximately 1,370 km (850 mi) of paved road and 980 km (610 mi) unpaved. Cyprus is one of only three EU nations in which vehicles drive on the left-hand side of the road, a remnant of British colonisation (the others being Ireland and Malta). A series of motorways runs along the coast from Paphos east to Ayia Napa, with two motorways running inland to Nicosia, one from Limassol and one from Larnaca.

Per capita private car ownership is the 29th-highest in the world.[190] There were approximately 344,000 privately owned vehicles, and a total of 517,000 registered motor vehicles in the Republic of Cyprus in 2006.[191] In 2006, plans were announced to improve and expand bus services and other public transport throughout Cyprus, with the financial backing of the European Union Development Bank. In 2010 the new bus network was implemented.[192]

Cyprus has several heliports and two international airports: Larnaca International Airport and Paphos International Airport. A third airport, Ercan International Airport, operates in the Turkish Cypriot administered area with direct flights only to Turkey (Turkish Cypriot ports are closed to international traffic apart from Turkey). Nicosia International Airport has been closed since 1974.

The main harbours of the island are Limassol and Larnaca, which service cargo, passenger and cruise ships.

Communications

Cyta, the state-owned telecommunications company, manages most telecommunications and Internet connections on the island. However, following deregulation of the sector, a few private telecommunications companies emerged, including epic, Cablenet, OTEnet Telecom, Omega Telecom and PrimeTel. In the Turkish-controlled area of Cyprus, two different companies administer the mobile phone network: Turkcell and KKTC Telsim.

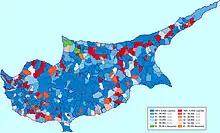

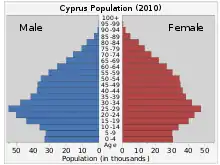

Demographics

According to the CIA World Factbook, in 2001 Greek Cypriots comprised 77%, Turkish Cypriots 18%, and others 5% of the Cypriot population.[193] At the time of the 2011 government census, there were 10,520 people of Russian origin living in Cyprus.[194][195][196][197]

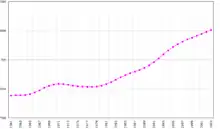

According to the first population census after the declaration of independence, carried out in December 1960 and covering the entire island, Cyprus had a total population of 573,566, of whom 442,138 (77.1%) were Greeks, 104,320 (18.2%) Turkish, and 27,108 (4.7%) others.[85][198]

Due to the inter-communal ethnic tensions between 1963 and 1974, an island-wide census was regarded as impossible. Nevertheless, the Cypriot government conducted one in 1973, without the Turkish Cypriot populace.[199] According to this census, the Greek Cypriot population was 482,000. One year later, in 1974, the Cypriot government's Department of Statistics and Research estimated the total population of Cyprus at 641,000; of whom 506,000 (78.9%) were Greeks, and 118,000 (18.4%) Turkish.[200] After the partition of the island in 1974, the government of Cyprus conducted six more censuses: in 1976, 1982, 1992, 2001, 2011 and 2021; these excluded the Turkish population which was resident in the northern part of the island.[198]

According to the Republic of Cyprus's estimate in 2005, the number of Cypriot citizens currently living in the Republic of Cyprus is around 871,036. In addition to this, the Republic of Cyprus is home to 110,200 foreign permanent residents[201] and an estimated 10,000–30,000 undocumented illegal immigrants currently living in the south of the island.[202] According to the Republic of Cyprus's website, the population was 856,857 at the Census in 2011 and 918,100 at the 2021 Census

| Largest groups of foreign residents | |

| Nationality | Population (2011) |

|---|---|

| 29,321 | |

| 24,046 | |

| 23,706 | |

| 18,536 | |

| 9,413 | |

| 8,164 | |

| 7,269 | |

| 7,028 | |

| 3,054 | |

| 2,933 | |

According to the 2006 census carried out by Northern Cyprus, there were 256,644 (de jure) people living in Northern Cyprus. 178,031 were citizens of Northern Cyprus, of whom 147,405 were born in Cyprus (112,534 from the north; 32,538 from the south; 371 did not indicate what part of Cyprus they were from); 27,333 born in Turkey; 2,482 born in the UK and 913 born in Bulgaria. Of the 147,405 citizens born in Cyprus, 120,031 say both parents were born in Cyprus; 16,824 say both parents born in Turkey; 10,361 have one parent born in Turkey and one parent born in Cyprus.[203]

In 2010, the International Crisis Group estimated that the total population of Cyprus was 1.1 million,[204] of which there was an estimated 300,000 residents in the north, perhaps half of whom were either born in Turkey or are children of such settlers.[205]

The villages of Rizokarpaso (in Northern Cyprus), Potamia (in Nicosia district) and Pyla (in Larnaca District) are the only settlements remaining with a mixed Greek and Turkish Cypriot population.[206]

Y-Dna haplogroups are found at the following frequencies in Cyprus: J (43.07% including 6.20% J1), E1b1b (20.00%), R1 (12.30% including 9.2% R1b), F (9.20%), I (7.70%), K (4.60%), A (3.10%).[207] J, K, F and E1b1b haplogroups consist of lineages with differential distribution within Middle East, North Africa and Europe.

Outside Cyprus there are significant and thriving diasporas - both a Greek Cypriot diaspora and a Turkish Cypriot diaspora - in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, the United States, Greece and Turkey.

Largest cities

Largest municipalities in Cyprus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

Nicosia (north and south)  Limassol |

1 | Nicosia (north and south) | Nicosia | 200,452 |  Strovolos  Larnaca | ||||

| 2 | Limassol | Limassol | 154,000 | ||||||

| 3 | Strovolos | Nicosia | 67,904 | ||||||

| 4 | Larnaca | Larnaca | 51,468 | ||||||

| 5 | Famagusta | Famagusta | 42,526 | ||||||

| 6 | Lakatamia | Nicosia | 38,435 | ||||||

| 7 | Kyrenia | Kyrenia | 33,207 | ||||||

| 8 | Paphos | Paphos | 32,892 | ||||||

| 9 | Kato Polemidhia | Limassol | 22,369 | ||||||

| 10 | Aglandjia | Nicosia | 20,783 | ||||||

Functional urban areas

| Functional urban areas | Population (2016)[208] |

| Nicosia | 330,000 |

| Limassol | 237,000 |

Religion

The majority of Greek Cypriots identify as Christians, specifically Greek Orthodox,[210][211][212] whereas most Turkish Cypriots are adherents of Sunni Islam. According to Eurobarometer 2005,[213] Cyprus was the second most religious state in the European Union at that time, after Malta (although in 2005 Romania wasn't in the European Union; currently Romania is the most religious state in the EU) (see Religion in the European Union). The first President of Cyprus, Makarios III, was an archbishop, and the Vice President of Cyprus was Fazıl Küçük. The current leader of the Greek Orthodox Church of Cyprus is Archbishop Chrysostomos II.

Hala Sultan Tekke, situated near the Larnaca Salt Lake is an object of pilgrimage for Muslims.

According to the 2001 census carried out in the Government-controlled area,[214] 94.8% of the population were Eastern Orthodox, 0.9% Armenians and Maronites, 1.5% Roman Catholics, 1.0% Church of England, and 0.6% Muslims. There is also a Jewish community on Cyprus. The remaining 1.3% adhered to other religious denominations or did not state their religion.

Languages

Cyprus has two official languages, Greek and Turkish.[215] Armenian and Cypriot Maronite Arabic are recognised as minority languages.[216][217] Although without official status, English is widely spoken and it features widely on road signs, public notices, and in advertisements, etc.[218] English was the sole official language during British colonial rule and the lingua franca until 1960, and continued to be used (de facto) in courts of law until 1989 and in legislation until 1996.[219] 80.4% of Cypriots are proficient in the English language as a second language.[220] Russian is widely spoken among the country's minorities, residents and citizens of post-Soviet countries, and Pontic Greeks. Russian, after English and Greek, is the third language used on many signs of shops and restaurants, particularly in Limassol and Paphos. In addition to these languages, 12% speak French and 5% speak German.[221]

The everyday spoken language of Greek Cypriots is Cypriot Greek and that of Turkish Cypriots is Cypriot Turkish.[219] These vernaculars both differ from their standard registers significantly.[219]

Education

Cyprus has a highly developed system of primary and secondary education offering both public and private education. The high quality of instruction can be attributed in part to the fact that nearly 7% of the GDP is spent on education which makes Cyprus one of the top three spenders of education in the EU along with Denmark and Sweden.[222]

State schools are generally seen as equivalent in quality of education to private-sector institutions. However, the value of a state high-school diploma is limited by the fact that the grades obtained account for only around 25% of the final grade for each topic, with the remaining 75% assigned by the teacher during the semester, in a minimally transparent way. Cypriot universities (like universities in Greece) ignore high school grades almost entirely for admissions purposes. While a high-school diploma is mandatory for university attendance, admissions are decided almost exclusively on the basis of scores at centrally administered university entrance examinations that all university candidates are required to take.

The majority of Cypriots receive their higher education at Greek, British, Turkish, other European and North American universities. Cyprus currently has the highest percentage of citizens of working age who have higher-level education in the EU at 30% which is ahead of Finland's 29.5%. In addition, 47% of its population aged 25–34 have tertiary education, which is the highest in the EU. The body of Cypriot students is highly mobile, with 78.7% studying in a university outside Cyprus.

Culture

Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots share a lot in common in their culture due to cultural exchanges but also have differences. Several traditional food (such as souvla and halloumi) and beverages are similar, as well as expressions and ways of life. Hospitality and buying or offering food and drinks for guests or others are common among both. In both communities, music, dance and art are integral parts of social life and many artistic, verbal and nonverbal expressions, traditional dances such as tsifteteli, similarities in dance costumes and importance placed on social activities are shared between the communities.[223] However, the two communities have distinct religions and religious cultures, with the Greek Cypriots traditionally being Greek Orthodox and Turkish Cypriots traditionally being Sunni Muslims, which has partly hindered cultural exchange.[224] Greek Cypriots have influences from Greece and Christianity, while Turkish Cypriots have influences from Turkey and Islam.

The Limassol Carnival Festival is an annual carnival which is held at Limassol, in Cyprus. The event which is very popular in Cyprus was introduced in the 20th century.[225]

Arts

The art history of Cyprus can be said to stretch back up to 10,000 years, following the discovery of a series of Chalcolithic period carved figures in the villages of Khoirokoitia and Lempa.[226] The island is the home to numerous examples of high quality religious icon painting from the Middle Ages as well as many painted churches. Cypriot architecture was heavily influenced by French Gothic and Italian renaissance introduced in the island during the era of Latin domination (1191–1571).

A well known traditional art that dates at least from the 14th century is the Lefkara lace (also known as "Lefkaratika", which originates from the village Lefkara. Lefkara lace is recognised as an intangible cultural heritage (ICH) by Unesco, and it is characterised by distinct design patterns, and its intricate, time-consuming production process. A genuine Lefkara lace with full embroidery can take typically hundreds of hours to be made, and that is why it is usually priced quite high. Another local form of art that originated from Lefkara is the production of Cypriot Filigree (locally known as Trifourenio), a type of jewellery that is made with twisted threads of silver. In Lefkara village there is government funded centre named Lefkara Handicraft Centre the mission of which is to educate and teach the art of making the embroidery and silver jewellery. There's also the Museum of Traditional Embroidery and Silversmithing located in the village which has large collection of local handmade art.

In modern times Cypriot art history begins with the painter Vassilis Vryonides (1883–1958) who studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice.[227] Arguably the two founding fathers of modern Cypriot art were Adamantios Diamantis (1900–1994) who studied at London's Royal College of Art and Christopheros Savva (1924–1968) who also studied in London, at Saint Martin's School of Art.[228] In 1960, Savva founded, together with Welsh artist Glyn Hughes, Apophasis [Decision], the first independent cultural centre of the newly established Republic of Cyprus. In 1968, Savva was among the artists representing Cyprus in its inaugural Pavilion at the 34th Venice Biennale. English Cypriot Artist Glyn HUGHES 1931–2014.[229] In many ways these two artists set the template for subsequent Cypriot art and both their artistic styles and the patterns of their education remain influential to this day. In particular the majority of Cypriot artists still train in England[230] while others train at art schools in Greece and local art institutions such as the Cyprus College of Art, University of Nicosia and the Frederick Institute of Technology.

One of the features of Cypriot art is a tendency towards figurative painting although conceptual art is being rigorously promoted by a number of art "institutions" and most notably the Nicosia Municipal Art Centre. Municipal art galleries exist in all the main towns and there is a large and lively commercial art scene.

Cyprus was due to host the international art festival Manifesta in 2006 but this was cancelled at the last minute following a dispute between the Dutch organizers of Manifesta and the Cyprus Ministry of Education and Culture over the location of some of the Manifesta events in the Turkish sector of the capital Nicosia.[231][232] There were also complaints from some Cypriot artists that the Manifesta organisation was importing international artists to take part in the event while treating members of the local art community in Cyprus as 'ignorant' and 'uncivilized natives' who need to be taught 'how to make proper art'.[233]

Other notable Greek Cypriot artists include Helene Black, Kalopedis family, Panayiotis Kalorkoti, Nicos Nicolaides, Stass Paraskos, Arestís Stasí, Telemachos Kanthos, Konstantia Sofokleous and Chris Achilleos, and Turkish Cypriot artists include İsmet Güney, Ruzen Atakan and Mutlu Çerkez.

Music

The traditional folk music of Cyprus has several common elements with Greek, Turkish, and Arabic Music, all of which have descended from Byzantine music, including Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot dances such as the sousta, syrtos, zeibekikos, tatsia, and karsilamas as well as the Middle Eastern-inspired tsifteteli and arapies. There is also a form of musical poetry known as chattista which is often performed at traditional feasts and celebrations. The instruments commonly associated with Cyprus folk music are the violin ("fkiolin"), lute ("laouto"), Cyprus flute (pithkiavlin), oud ("outi"), kanonaki and percussions (including the "tamboutsia"). Composers associated with traditional Cypriot music include Solon Michaelides, Marios Tokas, Evagoras Karageorgis and Savvas Salides. Among musicians is also the acclaimed pianist Cyprien Katsaris, composer Andreas G. Orphanides, and composer and artistic director of the European Capital of Culture initiative Marios Joannou Elia.

Popular music in Cyprus is generally influenced by the Greek Laïka scene; artists who play in this genre include international platinum star Anna Vissi,[234][235][236][237] Evridiki, and Sarbel. Hip hop and R&B have been supported by the emergence of Cypriot rap and the urban music scene at Ayia Napa, while in the last years the reggae scene is growing, especially through the participation of many Cypriot artists at the annual Reggae Sunjam festival. Is also noted Cypriot rock music and Éntekhno rock is often associated with artists such as Michalis Hatzigiannis and Alkinoos Ioannidis. Metal also has a small following in Cyprus represented by bands such as Armageddon (rev.16:16), Blynd, Winter's Verge, Methysos and Quadraphonic.

Literature

_-_BEIC_6353768.jpg.webp)

Literary production of the antiquity includes the Cypria, an epic poem, probably composed in the late 7th century BC and attributed to Stasinus. The Cypria is one of the first specimens of Greek and European poetry.[238] The Cypriot Zeno of Citium was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy.

Epic poetry, notably the "acritic songs", flourished during Middle Ages. Two chronicles, one written by Leontios Machairas and the other by Georgios Boustronios, cover the entire Middle Ages until the end of Frankish rule (4th century–1489). Poèmes d'amour written in medieval Greek Cypriot date back from the 16th century. Some of them are actual translations of poems written by Petrarch, Bembo, Ariosto and G. Sannazzaro.[239] Many Cypriot scholars fled Cyprus at troubled times such as Ioannis Kigalas (c. 1622–1687) who migrated from Cyprus to Italy in the 17th century, several of his works have survived in books of other scholars.[240]

Hasan Hilmi Efendi, a Turkish Cypriot poet, was rewarded by the Ottoman sultan Mahmud II and said to be the "sultan of the poems".[242]

Modern Greek Cypriot literary figures include the poet and writer Kostas Montis, poet Kyriakos Charalambides, poet Michalis Pasiardis, writer Nicos Nicolaides, Stylianos Atteshlis, Altheides, Loukis Akritas[243] and Demetris Th. Gotsis. Dimitris Lipertis, Vasilis Michaelides and Pavlos Liasides are folk poets who wrote poems mainly in the Cypriot-Greek dialect.[244][245] Among leading Turkish Cypriot writers are Osman Türkay, twice nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature,[246] Özker Yaşın, Neriman Cahit, Urkiye Mine Balman, Mehmet Yaşın and Neşe Yaşın.

There is an increasingly strong presence of both temporary and permanent emigre Cypriot writers in world literature, as well as writings by second and third -generation Cypriot writers born or raised abroad, often writing in English. This includes writers such as Michael Paraskos and Stephanos Stephanides.[247]

Examples of Cyprus in foreign literature include the works of Shakespeare, with most of the play Othello by William Shakespeare set on the island of Cyprus. British writer Lawrence Durrell lived in Cyprus from 1952 until 1956, during his time working for the British colonial government on the island, and wrote the book Bitter Lemons about his time in Cyprus which won the second Duff Cooper Prize in 1957.

Mass media

In the 2015 Freedom of the Press report of Freedom House, the Republic of Cyprus and Northern Cyprus were ranked "free". The Republic of Cyprus scored 25/100 in press freedom, 5/30 in Legal Environment, 11/40 in Political Environment, and 9/30 in Economic Environment (the lower scores the better).[248] Reporters Without Borders rank the Republic of Cyprus 24th out of 180 countries in the 2015 World Press Freedom Index, with a score of 15.62[249]

The law provides for freedom of speech and press, and the government generally respects these rights in practice. An independent press, an effective judiciary, and a functioning democratic political system combine to ensure freedom of speech and of the press. The law prohibits arbitrary interference with privacy, family, home, or correspondence, and the government generally respects these prohibitions in practice.[250]

Local television companies in Cyprus include the state owned Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation which runs two television channels. In addition on the Greek side of the island there are the private channels ANT1 Cyprus, Plus TV, Mega Channel, Sigma TV, Nimonia TV (NTV) and New Extra. In Northern Cyprus, the local channels are BRT, the Turkish Cypriot equivalent to the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation, and a number of private channels. The majority of local arts and cultural programming is produced by the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation and BRT, with local arts documentaries, review programmes and filmed drama series.

Cinema

The most worldwide known Cypriot director, to have worked abroad, is Michael Cacoyannis.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, George Filis produced and directed Gregoris Afxentiou, Etsi Prodothike i Kypros, and The Mega Document. In 1994, Cypriot film production received a boost with the establishment of the Cinema Advisory Committee. In 2000, the annual amount set aside for filmmaking in the national budget was CYP£500,000 (about €850,000). In addition to government grants, Cypriot co-productions are eligible for funding from the Council of Europe's Eurimages Fund, which finances European film co-productions. To date, four feature films on which a Cypriot was an executive producer have received funding from Eurimages. The first was I Sphagi tou Kokora (1996), followed by Hellados (unreleased), To Tama (1999), and O Dromos gia tin Ithaki (2000).[251]

Only a small number of foreign films have been made in Cyprus. This includes Incense for the Damned (1970), The Beloved (1970), and Ghost in the Noonday Sun (1973).[252] Parts of the John Wayne film The Longest Day (1962) were also filmed in Cyprus.

Cuisine

During the medieval period, under the French Lusignan monarchs of Cyprus an elaborate form of courtly cuisine developed, fusing French, Byzantine and Middle Eastern forms. The Lusignan kings were known for importing Syrian cooks to Cyprus, and it has been suggested that one of the key routes for the importation of Middle Eastern recipes into France and other Western European countries, such as blancmange, was via the Lusignan Kingdom of Cyprus. These recipes became known in the West as vyands de Chypre, or foods of Cyprus, and the food historian William Woys Weaver has identified over one hundred of them in English, French, Italian and German recipe books of the Middle Ages. One that became particularly popular across Europe in the medieval and early modern periods was a stew made with chicken or fish called malmonia, which in English became mawmeny.[253]

Another example of a Cypriot food ingredient entering the Western European canon is the cauliflower, still popular and used in a variety of ways on the island today, which was associated with Cyprus from the early Middle Ages. Writing in the 12th and 13th centuries the Arab botanists Ibn al-'Awwam and Ibn al-Baitar claimed the vegetable had its origins in Cyprus,[254][255] and this association with the island was echoed in Western Europe, where cauliflowers were originally known as Cyprus cabbage or Cyprus colewart. There was also a long and extensive trade in cauliflower seeds from Cyprus, until well into the sixteenth century.[256]

Although much of the Lusignan food culture was lost after the fall of Cyprus to the Ottomans in 1571, a number of dishes that would have been familiar to the Lusignans survive today, including various forms of tahini and houmous, zalatina, skordalia and pickled wild song birds called ambelopoulia. Ambelopoulia, which is today highly controversial, and illegal, was exported in vast quantities from Cyprus during the Lusignan and Venetian periods, particularly to Italy and France. In 1533 the English traveller to Cyprus, John Locke, claimed to have seen the pickled wild birds packed into large jars, or which 1200 jars were exported from Cyprus annually.[257]

Also familiar to the Lusignans would have been Halloumi cheese, which some food writers today claim originated in Cyprus during the Byzantine period[258][259][260] although the name of the cheese itself is thought by academics to be of Arabic origin.[261] There is no surviving written documentary evidence of the cheese being associated with Cyprus before the year 1554, when the Italian historian Florio Bustron wrote of a sheep-milk cheese from Cyprus he called calumi.[261] Halloumi (Hellim) is commonly served sliced, grilled, fried and sometimes fresh, as an appetiser or meze dish.

Seafood and fish dishes include squid, octopus, red mullet, and sea bass. Cucumber and tomato are used widely in salads. Common vegetable preparations include potatoes in olive oil and parsley, pickled cauliflower and beets, asparagus and taro. Other traditional delicacies are meat marinated in dried coriander seeds and wine, and eventually dried and smoked, such as lountza (smoked pork loin), charcoal-grilled lamb, souvlaki (pork and chicken cooked over charcoal), and sheftalia (minced meat wrapped in mesentery). Pourgouri (bulgur, cracked wheat) is the traditional source of carbohydrate other than bread, and is used to make the delicacy koubes.

Fresh vegetables and fruits are common ingredients. Frequently used vegetables include courgettes, green peppers, okra, green beans, artichokes, carrots, tomatoes, cucumbers, lettuce and grape leaves, and pulses such as beans, broad beans, peas, black-eyed beans, chick-peas and lentils. The most common fruits and nuts are pears, apples, grapes, oranges, mandarines, nectarines, medlar, blackberries, cherry, strawberries, figs, watermelon, melon, avocado, lemon, pistachio, almond, chestnut, walnut, and hazelnut.

Cyprus is also well known for its desserts, including lokum (also known as Turkish Delight) and Soutzoukos.[262] This island has protected geographical indication (PGI) for its lokum produced in the village of Geroskipou.[263][264]

Sports

Sport governing bodies include the Cyprus Football Association, Cyprus Basketball Federation, Cyprus Volleyball Federation, Cyprus Automobile Association, Cyprus Badminton Federation,[265] Cyprus Cricket Association, Cyprus Rugby Federation and the Cyprus Pool Association.

Notable sports teams in the Cyprus leagues include APOEL FC, Anorthosis Famagusta FC, AC Omonia, AEL Lemesos, Apollon FC, Nea Salamis Famagusta FC, Olympiakos Nicosia, AEK Larnaca FC, AEL Limassol B.C., Keravnos B.C. and Apollon Limassol B.C. Stadiums or sports venues include the GSP Stadium (the largest in the Republic of Cyprus-controlled areas), Tsirion Stadium (second largest), Neo GSZ Stadium, Antonis Papadopoulos Stadium, Ammochostos Stadium and Makario Stadium.

In the 2008–09 season, Anorthosis Famagusta FC was the first Cypriot team to qualify for the UEFA Champions League Group stage. Next season, APOEL FC qualified for the UEFA Champions League group stage, and reached the last 8 of the 2011–12 UEFA Champions League after finishing top of its group and beating French Olympique Lyonnais in the Round of 16.

The Cyprus national rugby union team known as The Moufflons currently holds the record for most consecutive international wins, which is especially notable as the Cyprus Rugby Federation was only formed in 2006.

Tennis player Marcos Baghdatis was ranked 8th in the world, was a finalist at the Australian Open, and reached the Wimbledon semi-final, all in 2006. High jumper Kyriakos Ioannou achieved a jump of 2.35 m at the 11th IAAF World Championships in Athletics in Osaka, Japan, in 2007, winning the bronze medal. He has been ranked third in the world. In motorsports, Tio Ellinas is a successful race car driver, currently racing in the GP3 Series for Marussia Manor Motorsport. There is also mixed martial artist Costas Philippou, who competes in the Ultimate Fighting Championship promotion's middleweight division. Costas holds a 6–3 record in UFC bouts, and recently defeated "The Monsoon" Lorenz Larkin by a knockout in the first round.

Also notable for a Mediterranean island, the siblings Christopher and Sophia Papamichalopoulou qualified for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. They were the only athletes who managed to qualify and thus represented Cyprus at the 2010 Winter Olympics.

The country's first ever Olympic medal, a silver medal, was won by the sailor Pavlos Kontides, at the 2012 Summer Olympics in the Men's Laser class.

See also

- Ancient regions of Anatolia

- Index of Cyprus-related articles

- Outline of Cyprus

Notes

- The Greek national anthem was adopted in 1966 by a decision of the Council of Ministers.[1]

- The vice presidency is reserved for a Turkish Cypriot. However the post has been vacant since the Turkish invasion in 1974.[4]

- Including Northern Cyprus, the UN buffer zone and Akrotiri and Dhekelia.

- Excluding Northern Cyprus.

- The .eu domain is also used, shared with other European Union member states.

- Greek: Κύπρος, romanized: Kýpros [ˈcipros]; Turkish: Kıbrıs [ˈkɯbɾɯs]