Paprika

Paprika (US /pəˈprikə/, /pæˈprikə/ (![]() listen);[1] UK /ˈpæprɪkə/, /pəˈpriːkə/[1]) is a spice made from dried and ground red peppers.[2] It is traditionally made from Capsicum annuum varietals in the Longum Group, which also includes chili peppers, but the peppers used for paprika tend to be milder and have thinner flesh.[3][4] In some languages, but not English, the word paprika also refers to the plant and the fruit from which the spice is made, as well as to peppers in the Grossum Group (e.g. bell peppers).[5][6]: 5, 73

listen);[1] UK /ˈpæprɪkə/, /pəˈpriːkə/[1]) is a spice made from dried and ground red peppers.[2] It is traditionally made from Capsicum annuum varietals in the Longum Group, which also includes chili peppers, but the peppers used for paprika tend to be milder and have thinner flesh.[3][4] In some languages, but not English, the word paprika also refers to the plant and the fruit from which the spice is made, as well as to peppers in the Grossum Group (e.g. bell peppers).[5][6]: 5, 73

.jpg.webp) Mallorcan pimentón tap de cortí paprika | |||||||

| 282 kcal (1181 kJ) | |||||||

| |||||||

All capsicum varieties are descended from wild ancestors in North America, in particular Central Mexico, where they have been cultivated for centuries. The peppers were subsequently introduced to the Old World, when peppers were brought to Spain in the 16th century. The seasoning is used to add color and flavor to many types of dishes in diverse cuisines.

The trade in paprika expanded from the Iberian Peninsula to Africa and Asia[6]: 8 and ultimately reached Central Europe through the Balkans, which was then under Ottoman rule. This helps explain the Hungarian origin of the English term. In Spanish, paprika has been known as pimentón since the 16th century, when it became a typical ingredient in the cuisine of western Extremadura.[6]: 5, 73 Despite its presence in Central Europe since the beginning of Ottoman conquests, it did not become popular in Hungary until the late 19th century.[7]

Paprika can range from mild to hot – the flavor also varies from country to country – but almost all plants grown produce the sweet variety.[8] Sweet paprika is mostly composed of the pericarp, with more than half of the seeds removed, whereas hot paprika contains some seeds, stalks, ovules, and calyces.[6]: 5, 73 The red, orange or yellow color of paprika is due to its content of carotenoids.[9]

History and etymology

Peppers, the raw material in paprika production, originated from North America, where they grow in the wild in Central Mexico and have for centuries been cultivated by the peoples of Mexico. The peppers were later introduced to the Old World, to Spain in the 16th century, as part of the Columbian Exchange.

The plant used to make the Hungarian version of the spice was grown in 1569 by the Turks at Buda[10] (now part of Budapest, the capital of Hungary). Central European paprika was hot until the 1920s, when a Szeged breeder found a plant that produced sweet fruit, which he grafted onto other plants.[8]

The first recorded use of the word paprika in English is from 1896,[10] although an earlier reference to Turkish paprika was published in 1831.[11] The word derives from the Hungarian word paprika,[12] which in turn came from the Latin piper or modern Greek piperi, ultimately from Sanskrit pippalī.[10] Paprika and similar words, including peperke, piperke, and paparka, are used in various languages for bell peppers.[6]: 5, 73

Production and varieties

Paprika is produced in various places including Argentina, Mexico, Hungary, Serbia, Spain, the Netherlands, China, and some regions of the United States.[13][14]

Hungarian

Hungary is a major source of paprika,[14] and it is the spice most closely associated with Hungary.[15] The spice was first used in Hungarian cuisine in the early 19th century.[15] It is available in different grades:

- Noble sweet (Édesnemes) – slightly pungent (the most commonly exported paprika; bright red)

- Special quality (különleges) – the mildest (very sweet with a deep bright red color)

- Delicate (csípősmentes csemege) – a mild paprika with a rich flavor (color from light to dark red)

- Exquisite delicate (csemegepaprika) – similar to delicate, but more pungent

- Pungent exquisite delicate (csípős csemege, pikáns) – an even more pungent version of delicate

- Rose (rózsa) – with a strong aroma and mild pungency (pale red)

- Semi-sweet (félédes) – a blend of mild and pungent paprikas; medium pungency

- Strong (erős) – the hottest paprika (light brown)[14]

Spanish (pimentón)

There are three versions of Spanish paprika (pimentón) – mild (pimentón dulce), mildly spicy (pimentón agridulce) and spicy (pimentón picante).

The most common Spanish paprika, Pimentón de la Vera, has a distinct smoky flavor and aroma, as it is dried by smoking, typically using oak wood.[16] Currently, according to the Denomination of Origin Regulation Council (Consejo Regulador de la DOP "Pimentón de La Vera"), the crop of La Vera paprika covers around 1,500 hectares and has an annual production of 4,500,000 kg, certified as Denomination of Origin.[17]

Pimentón de Murcia is an unsmoked variety made with bola/ñora peppers[18] and traditionally dried in the sun or in kilns.[19]

Usage

Culinary

Paprika is used as an ingredient in numerous dishes throughout the world. It is principally used to season and color rice, stews, and soups, such as goulash, and in the preparation of sausages such as Spanish chorizo, mixed with meats and other spices. In the United States, paprika is frequently sprinkled raw on foods as a garnish, but the flavor contained within the oleoresin is more effectively brought out by heating it in oil.[20]

Hungarian national dishes incorporating paprika include gulyas (goulash), a meat stew, and paprikash (paprika gravy: a Hungarian recipe combining meat or chicken, broth, paprika, and sour cream). In Moroccan cuisine, paprika (tahmira) is usually augmented by the addition of a small amount of olive oil blended into it. Many dishes call for paprika (colorau) in Portuguese cuisine for taste and color.

Carotenoids

The red, orange, or yellow color of paprika powder derives from its mix of carotenoids.[9] Yellow-orange paprika colors derive primarily from α-carotene and β-carotene (provitamin A compounds), zeaxanthin, lutein and β-cryptoxanthin, whereas red colors derive from capsanthin and capsorubin.[9] One study found high concentrations of zeaxanthin in orange paprika.[21] The same study found that orange paprika contains much more lutein than red or yellow paprika.[21]

See also

- Ajvar

- Cayenne pepper

- Chili powder

- Crushed red pepper

- Food powder

- List of Capsicum cultivars

- List of smoked foods

- Paprika Tap de Cortí

- Pimiento

Gallery

The various shapes and colors of the peppers used to prepare paprika

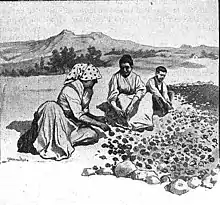

The various shapes and colors of the peppers used to prepare paprika.jpg.webp) Paprika pepper farmer in Tanzania

Paprika pepper farmer in Tanzania Red peppers in Cachi, Argentina are air-dried before being processed into powder.

Red peppers in Cachi, Argentina are air-dried before being processed into powder.

Smoked paprika, called pimentón in Spanish

Smoked paprika, called pimentón in Spanish

References

- "paprika". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "pepper". Retrieved April 7, 2017 – via The Free Dictionary.

- Derera, Nicholas F.; Nagy, Natalia; Hoxha, Adriana (January 2005). "Condiment paprika research in Australia". Journal of Business Chemistry. 2 (1): 4–18.

- Vaughan, John; Geissler, Catherine (2009). The New Oxford Book of Food Plants (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 9780191609497.

- Azhar Ali Farooqi; B. S. Sreeramu; K. N. Srinivasappa (2005). Cultivation of Spice Crops. Universities Press. pp. 336–. ISBN 978-81-7371-521-1. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- Andrews, Jean (1995). Peppers: The Domesticated Capsicums (New ed.). Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780292704671. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- Ayto, John (1990). The Glutton's Glossary: A Dictionary of Food and Drink Terms. London: Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 9780415026475. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- Sasvari, Joanne (2005). Paprika: A Spicy Memoir from Hungary. Toronto, ON: CanWest Books. p. 202. ISBN 9781897229057. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- Gómez-García Mdel, R; Ochoa-Alejo, N (2013). "Biochemistry and molecular biology of carotenoid biosynthesis in chili peppers (Capsicum spp.)". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 14 (9): 19025–53. doi:10.3390/ijms140919025. PMC 3794819. PMID 24065101.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- Lieber, Francis (1831). Encyclopaedia Americana. p. 476. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- A Magyar Nyelv Történeti-Etimológiai Szótára [The Historical-Etymological Dictionary of the Hungarian Language]. Vol. 3. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. 1976. p. 93.

- "Paprika — Food Facts". Food Reference. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- NIIR Board of Consultants & Engineers (2006). The Complete Book on Spices & Condiments (With Cultivation, Processing & Uses) (2nd ed.). Asia Pacific Business Press. pp. 133–135. ISBN 8178330385.

- Gergely, Anikó (2008). Culinaria Hungary. Ruprecht Stempell, Christoph Büschel, Mo Croasdale. Potsdam, Germany: H.F. Ullmann. pp. 16–23. ISBN 978-3-8331-4996-2. OCLC 566879902.

- "Spanish Paprika — Pimentón". Spanishfood.about.com. March 2, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- "Pimentón de La Vera: The King of Spanish Kitchens". Spanish Club Blog. April 16, 2022.

- "Ñora". Foods and Wines from Spain. ICEX. July 22, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

The ñora is a dried pepper mainly used to make pimentón (a type of Spanish paprika) in Murcia and to season dishes

- "Pimentón, or Spanish Paprika: Where It Comes from, How It's Made, and More". The Spruce. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- "Paprika - an overview s". Sciencedirect.com. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- Kim, Ji-Sun (2016). "Carotenoid profiling from 27 types of paprika (Capsicum annuum L.) with different colors, shapes, and cultivation methods". Food Chemistry. 201: 64–71. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.041. PMID 26868549.

- "Nutrient content for paprika in a one teaspoon amount". Conde Nast for the US Department of Agriculture National Nutrient Database, Standard Release 21. 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

External links

The dictionary definition of paprika at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of paprika at Wiktionary