Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (pronounced [ˈpaʊl ˈluːtvɪç hans ˈantoːn fɔn ˈbɛnəkn̩dɔʁf ʔʊnt fɔn ˈhɪndn̩bʊʁk] (![]() listen); abbreviated pronounced [ˈpaʊl fɔn ˈhɪndn̩bʊʁk] (

listen); abbreviated pronounced [ˈpaʊl fɔn ˈhɪndn̩bʊʁk] (![]() listen); 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany from 1925 until his death in 1934. During his presidency, he played a key role in the Nazi seizure of power in January 1933 when, under pressure from advisers, he appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany.

listen); 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany from 1925 until his death in 1934. During his presidency, he played a key role in the Nazi seizure of power in January 1933 when, under pressure from advisers, he appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany.

Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg | |

|---|---|

Hindenburg in the 1920s | |

| President of Germany | |

| In office 12 May 1925 – 2 August 1934 | |

| Chancellor |

|

| Preceded by | Friedrich Ebert |

| Succeeded by | Adolf Hitler (as Führer) |

| Chief of the German Great General Staff | |

| In office 29 August 1916 – 3 July 1919 | |

| Deputy | Erich Ludendorff (as First Quartermaster-General) |

| Preceded by | Erich von Falkenhayn |

| Succeeded by | Wilhelm Groener |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 October 1847 Posen, Kingdom of Prussia (now Poznań, Poland) |

| Died | 2 August 1934 (aged 86) Neudeck, East Prussia, Nazi Germany (now Ogrodzieniec, Poland) |

| Resting place | St. Elizabeth's Church, Marburg |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse | Gertrud von Sperling

(m. 1879; died 1921) |

| Children | 3, including Oskar |

| Relatives | Erich von Manstein (nephew) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Pour le Mérite with oak leaves |

Hindenburg was born to a family of minor Prussian nobility in Posen. Upon completing his education as a cadet, he enlisted in the Third Regiment of Foot Guards as a second lieutenant. He then saw combat during the Austro-Prussian and Franco-Prussian wars. In 1873, he was admitted to the prestigious Kriegsakademie in Berlin, where he studied for three years before being appointed to the Army's General Staff Corps. Later in 1885, he was promoted to the rank of major and became a member of the Great General Staff. Following a five-year teaching stint at the Kriegsakademie, Hindenburg steadily rose through the army's ranks to become a lieutenant-general by 1900. Around the time of his promotion to General of the Infantry in 1905, Count Alfred von Schlieffen recommended that he succeed him as Chief of the Great General Staff but the post ultimately went to Helmuth von Moltke in January 1906. In 1911, Hindenburg announced his retirement from the military.

Following World War I's outbreak in July 1914, he was recalled to military service and quickly achieved fame on the Eastern Front as the victor of Tannenberg. Subsequently, he oversaw a crushing series of victories against the Russians that made him a national hero and the center of a massive personality cult. By 1916, Hindenburg's popularity had risen to the point that he replaced General Erich von Falkenhayn as Chief of the Great General Staff.[1] Thereafter, he and his deputy, General Erich Ludendorff, exploited Emperor Wilhelm II's broad delegation of power to the German Supreme Army Command to establish a de facto military dictatorship. Under their leadership, Germany secured Russia's defeat in the east and achieved advances on the Western Front deeper than any seen since the conflict's outbreak. However, by the end of 1918, all improvements in Germany's fortunes were reversed after the German Army was decisively defeated in the Second Battle of the Marne and the Allies' Hundred Days Offensive. Upon his country's capitulation to the Allies in the November 1918 armistice, Hindenburg stepped down as Germany's commander-in-chief before retiring once again from military service in 1919.

In 1925, Hindenburg returned to public life to become the second elected president of the German Weimar Republic. While personally opposed to Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party, he nonetheless played a major role in the political instability that resulted in their rise to power. Upon twice dissolving the Reichstag in 1932, Hindenburg agreed in January 1933 to appoint Hitler as Chancellor in coalition with the Deutschnationale Volkspartei. In response to the Reichstag fire allegedly committed by Marinus van der Lubbe, he approved the Reichstag Fire Decree in February 1933 which suspended various civil liberties. Later in March, he signed the Enabling Act of 1933 which gave the Nazi regime emergency powers. After Hindenburg died the following year, Hitler combined the presidency with his office as chancellor before proceeding to declare himself Führer und Reichskanzler des deutschen Volkes (lit. 'Leader and Reich Chancellor of the German People') and transformed Germany into a totalitarian state.

Early life

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg was born in Posen, Prussia the son of Prussian junker Hans Robert Ludwig von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1816–1902) and his wife Luise Schwickart (1825–1893), the daughter of physician Karl Ludwig Schwickart and wife Julie Moennich. His paternal grandparents were Otto Ludwig Fady von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1778–1855), through whom he was remotely descended from the illegitimate daughter of Count Heinrich VI of Waldeck, and his wife Eleonore von Brederfady (d. 1863). Hindenburg was also a direct descendant of Martin Luther and his wife Katharina von Bora, through their daughter Margarethe Luther. Hindenburg's younger brothers and sister were Otto (b. 1849), Ida (b. 1851) and Bernhard (b. 1859). His family were all Lutheran Protestants in the Evangelical Church of Prussia, which since 1817 included both Calvinist and Lutheran parishioners.

Paul was proud of his family and could trace ancestors back to 1289.[3] The dual surname was adopted in 1789 to secure an inheritance and appeared in formal documents, but in everyday life they were von Beneckendorffs. True to family tradition his father supported his family as an infantry officer; he retired as a major. In the summer they visited his grandfather at the Hindenburg estate of Neudeck in East Prussia. At age 11 Paul entered the Cadet Corps School at Wahlstatt (now Legnickie Pole, Poland). At 16 he was transferred to the School in Berlin, and at 18 he served as a page to the widow of King Frederick William IV of Prussia. Graduates entering the army were presented to King William I, who asked for their father's name and rank. He became a second lieutenant in the Third Regiment of Foot Guards.

In the Prussian Army

Action in two wars

When the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 broke out Hindenburg wrote his parents: "I rejoice in this bright-coloured future. For the soldier war is the normal state of things…If I fall, it is the most honorable and beautiful death".[4] During the decisive Battle of Königgrätz he was briefly knocked unconscious by a bullet that pierced his helmet and creased the top of his skull. Quickly regaining his senses, he wrapped his head in a towel and resumed leading his detachment, winning a decoration.[5] He was battalion adjutant when the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) broke out. After weeks of marching, the Guards attacked the village of Saint Privat (near Metz). Climbing a gentle slope, they came under heavy fire from the superior French rifles. After four hours the Prussian artillery came up to blast the French lines while the infantry, filled with the "holy lust of battle",[6] swept through the French lines. His regiment suffered 1096 casualties, and he became regimental adjutant. The Guards were spectators at the Battle of Sedan and for the following months sat in the siege lines surrounding Paris. He was his regiment's elected representative at the Palace of Versailles when the German Empire was proclaimed on 18 January 1871; at 1.98 m (6 feet 6 inches) tall with a muscular frame and striking blue eyes, he was an impressive figure.[7] After the French surrender he watched from afar the suppression of the Paris Commune.

General Staff

In 1873 he passed in the highly competitive entrance examination for admission to the Kriegsakademie in Berlin.[8] After three years of study, his grades were high enough for an appointment with the General Staff. He was promoted to captain in 1878 and assigned to the staff of the II Corps. He married the intelligent and accomplished Gertrud von Sperling (1860–1921), daughter of General Oskar von Sperling, in 1879. The couple would have two daughters, Irmengard Pauline (1880) and Annemaria (1891), and one son, Oskar (1883). Next, he commanded an infantry company, in which his men were ethnic Poles.

He was transferred in 1885 to the General Staff and was promoted to major. His section was led by Count Alfred von Schlieffen, a student of encirclement battles like Cannae, whose Schlieffen Plan proposed to pocket the French Army. For five years Hindenburg also taught tactics at the Kriegsakademie. At the maneuvers of 1885, he met the future Kaiser Wilhelm II; they met again at the next year's war game in which Hindenburg commanded the "Russian army". He learned the topography of the lakes and sand barrens of East Prussia during the annual Great General Staff's ride in 1888. The following year he moved to the War Ministry, to write the field service regulations on field-engineering and on the use of heavy artillery in field engagements; both were used during the First World War. He became a lieutenant-colonel in 1891, and two years later was promoted to colonel commanding an infantry regiment. He became chief of staff of the VIII Corps in 1896.

Field commands and retirement

Hindenburg became a major-general (equivalent to a British and US brigadier general) in 1897; and in 1900 he was promoted to lieutenant general (equivalent to major-general) and received command of the 28th Infantry Division. Five years later he was made commander of the IV Corps based in Magdeburg as a General of the Infantry (lieutenant-general; the German equivalent to four-star rank was Colonel-General). The annual maneuvers taught him how to maneuver a large force; in 1908 he defeated a corps commanded by the Kaiser.[9] Schlieffen recommended him as Chief of the General Staff in 1909, but he lost out to Helmuth von Moltke.[10] He retired in 1911 "to make way for younger men".[11] He had been in the army for 46 years, including 14 years in General Staff positions. During his career, Hindenburg did not have political ambitions and remained a staunch monarchist.[12]

World War I

1914

_von_Nicola_Perscheid_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Assumption of command in East Prussia

When WWI broke out, Hindenburg was retired in Hannover. On 22 August, he was selected by the War Cabinet and the German Supreme Army Command (Oberste Heeresleitung, OHL) to assume command of the German Eighth Army in East Prussia, with General Erich Ludendorff as his chief of staff.[1][12] After the Eighth Army had been defeated by the Russian 1st Army at Gumbinnen, it had found itself in danger of encirclement as the Russian 2nd Army under General Alexander Samsonov advanced from the south towards the Vistula River. Momentarily panicked, Eighth Army commander Maximilian von Prittwitz notified OHL of his intent to withdraw his forces into Western Prussia.[13] The Chief of the German General Staff, Generaloberst Helmuth von Moltke, responded by relieving Prittwitz and replacing him with Hindenburg.[14]

Tannenberg

Upon arriving at Marienberg on 23 August, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were met by members of the 8th Army's staff led by Lieutenant Colonel Max Hoffmann, an expert on the Russian army. Hoffman informed them of his plans to shift part of the 8th Army south to attack the exposed left flank of the advancing Russian Second Army.[15] Agreeing with Hoffman's strategy, Hindenburg authorized Ludendorff to transfer most of the 8th Army south while leaving only two cavalry brigades to face the Russian First Army in the north.[16] In Hindenburg's words the line of soldiers defending Germany's border against was "thin, but not weak", because the men were defending their homes.[17] If pushed too hard by the Second Army, he believed they would cede ground only gradually as German reinforcements continued to mass on the invading Russians' flanks before ultimately encircling and annihilating them.[18] On the eve of the ensuing battle, Hindenburg reportedly strolled close to the decaying walls of the fortress of the Knights of Prussia, recalling how the Knights of Prussia were defeated by the Slavs in 1410 at nearby Tannenberg.[19]

On the night of August 25th, Hindenburg told his staff, "Gentlemen, our preparations are so well in hand that we can sleep soundly tonight".[20] On the day of the battle, Hindenburg reportedly watched from a hilltop as his forces' weak center gradually gave ground until the sudden roar of German guns to his right heralded the surprise attack on the Russians' flanks. Ultimately, the Battle of Tannenberg resulted in the destruction of the Russian 2nd Army, with 92,000 Russians captured together with four hundred guns.[21] while German casualties numbered only 14,000. According to British field marshal Edmund Ironside it was the "greatest defeat suffered by any of the combatants during the war".[22] Recognizing the victory's propaganda value, Hindenburg suggested naming the battle "Tannenberg" as a way of "avenging" the defeat inflicted on the Order of the Teutonic Knights by the Polish and Lithuanian knights in 1410, even though it was fought nowhere near the field of Tannenberg.[23]

After this decisive victory Hindenburg repositioned the Eighth Army to face the Russian First Army. Hindenburg's tactics spurned head-on attacks all along the front in favor of schwerpunkts, sharp, localized hammer blows.[24] Two schwerpunkts struck in the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes, from these breakthrough points two columns drove east to pocket the Russians led by General Paul von Rennenkampf, who managed to retreat 100 km (62 mi) with heavy losses. In the first six weeks of the war the Russians had lost more than 310,000 men.[25] Eight hundred thousand refugees were able to return to their East Prussian homes, thanks to victories that strikingly contrasted with the bloody deadlock that characterized the Western Front following the failure of the Schlieffen Plan.

Partnership with Ludendorff

The Hindenburg-Ludendorff duo's successful performance on the Eastern Front in 1914 marked the beginning of a military and political partnership that lasted until the end of the war. As Hindenburg wrote to the Kaiser a few months later: "[Ludendorff] has become my faithful adviser and a friend who has my complete confidence and cannot be replaced by anyone."[26] Despite their strikingly dissimilar temperaments, the older general's calm decisiveness proved to be an outstanding fit for Ludendorff's energy and tactical ingenuity. When Ludendorff's nerves twice drove him to consider changing their plans for Tannenberg at the last minute; both times Hindenburg talked to him privately and his confidence wavered no further.[27]

Defending Silesia

On the east bank of the Vistula in Poland the Russians were mobilizing new armies which were shielded from attack by the river; once assembled they would cross the river to march west into Silesia. To counter the Russians' pending invasion of Silesia, Hindenburg advanced into Poland and occupied the west bank of the Vistula opposite from where Russian forces were mobilizing. He set up headquarters at Posen in West Prussia, accompanied by Ludendorff and Hoffmann.[28] When the Russians attempted to cross the Vistula, the German forces under his command held firm, but the Russians were able to cross in the Austro-Hungarian sector to the south. Hindenburg retreated and destroyed all railways and bridges so that the Russians would be unable to advance beyond 120 km (75 mi) west of their railheads—well short of the German frontier.[29]

On 1 November 1914 Hindenburg was appointed Ober Ost (commander in the east) and was promoted to field marshal. To meet the Russians' renewed push into Silesia, Hindenburg moved Ninth Army by rail north to Thorn and reinforced it with two corps from Eighth Army. On 11 November, in a raging snowstorm, his forces surprised the Russian flank in the fierce Battle of Łódź, which ended the immediate Russian threat to Silesia and also captured Poland's second largest city.

Disagreements with Falkenhayn

Hindenburg argued that the still miserably equipped Russians—some only carried spears—in the huge Polish salient were in a trap in which they could be snared in a cauldron by a southward pincer from East Prussia and a northward pincer from Galicia, using motor vehicles for speed,[30] even though the Russians outnumbered the Germans by three to one. From Hindenburg's point of view, such an overwhelming triumph could end the war in the Eastern Front.[31] Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of Germany's Great General Staff, rejected his plan as a pipe dream. Nevertheless, urged on by Ludendorff and Hoffman, Hindenburg spent the winter fighting for his strategy by badgering the Kaiser while his press officer recruited notables like the Kaiserin and the Crown Prince to "stab the Kaiser in the back".[32] The Kaiser compromised by keeping Falkenhayn in supreme command, but replacing him as Prussian war minister. In retaliation, Falkenhayn reassigned some of Hindenburg's forces to a new army group under Prince Leopold of Bavaria and transferring Ludendorff to a new joint German and Austro-Hungarian Southern Army. Hindenburg and Ludendorff reacted by threatening to resign thereby resulting in Ludendorff's reinstatement under Hindenburg's command.

Counterattacks in East Prussia and Poland

Following his return, Ludendorff provided Hindenburg with a depressing evaluation of their allies' army, which already had lost many of their professional officers[33] and had been driven out of much of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, their part of what once had been Poland. Meanwhile, the Russians were inexorably pushing from Galicia toward Hungary through the Carpathian passes. Under orders from Falkenhayn to contain the resurgent Russians, Hindenburg mounted an unsuccessful attack in Poland with his Ninth Army as well as an offensive by the newly formed Tenth Army which made only local gains. Following these setbacks, he set up temporary headquarters at Insterburg, and made plans to eliminate the Russians' remaining toehold in East Prussia by ensnaring them in a pincer movement between the Tenth Army in the north and Eighth Army in the south. The attack was launched on 7 February whereby Hindenburg's forces encircled an entire corps and captured more than 100,000 men in the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes.

Shortly thereafter, Hindenburg and Ludendorff played a key role in the Central Powers' Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive. After the Austro-Hungarian fortress of Przemyśl fell on 23 March, Austria-Hungary's high command pushed for a joint strike on the Russian right flank that could potentially drive their forces out of the Carpathians. Agreeing to the proposal, Falkenhayn moved OHL east to the castle of Pless while forming Army Group von Mackensen from a new German Eleventh Army and the Austro-Hungarian Fourth Army. As Field Marshal August von Mackensen broke through Russian lines between Gorlice and Tarnów, Hindenburg's Ninth and Tenth Army launched diversionary attacks that threatened Riga in the north.[34] In one of the war's most successful cavalry actions, three cavalry divisions swept east into Courland, the barren, sandy region near the Baltic coast. The cavalry's gains were held by Hindenburg's new Nieman army, named after the river.

In June, the Supreme Army Command ordered Hindenburg to launch a frontal attack in Poland toward the Narew River north of Warsaw. Hindenburg created Army Group Gallwitz—named after its commander—which when Berlin approved became Twelfth Army (Von Gallwitz is one of many able commanders selected by Hindenburg), who stayed at the new army's headquarters to be available if needed. They broke through the Russian lines after a brief, but intense bombardment directed by Lieutenant Colonel Georg Bruchmüller, an artillery genius recalled from medical retirement. One-third of the opposing Russian First Army were casualties in the first five hours.[35] From then on Hindenburg often called on Bruchmüller. The Russians withdrew until they sheltered behind the Narev River. However, steamroller frontal attacks cost dearly: by 20 August Gallwitz had lost 60,000 men.

Evacuation of Poland

As the Russians withdrew from the Polish salient, Falkenhayn insisted on pursuing them into Lithuania. However, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were dissatisfied with this plan. Hindenburg would later claim that he saw it as "a pursuit in which the pursuer gets more exhausted than the pursued".[36]

On 1 June, Hindenburg's Nieman and Tenth Armies spearheaded attacks into Courland in an attempt to pocket the defenders. Ultimately, this plan was foiled by the prudent commander of the Fifth Russian Army who defied orders by pulling back into defensible positions shielding Riga.[37]

Despite the setback in Latvia, Hindenburg and Ludendorff continued to rack up victories on the Eastern Front. The German Tenth Army besieged Kovno, a Lithuanian city on the Nieman River defended by a circle of forts. It fell on 17 August, along with 1,300 guns and almost 1 million shells. On 5 August his forces were consolidated into Army Group Hindenburg, which took the city of Grodno after bitter street fighting, but the retreating defenders could not be trapped because the wretched rail lines lacked the capacity to bring up the needed men. They occupied Vilnius on 18 September, then halted on ground favorable for a defensive line. On 6 August, German troops under Hindenburg used chlorine gas against Russian troops defending Osowiec Fortress. The Russians demolished much of Osowiec and withdrew on 18 August.

In October, Hindenburg moved headquarters to Kovno. They were responsible for 108,800 km2 (42,000 mi2) of conquered Russian territory, which was home to three million people and became known as Ober Ost. The troops built fortifications on the eastern border while Ludendorff "with his ruthless energy"[38] headed the civil government, using forced labor to repair the war damages and to dispatch useful products, like hogs, to Germany. A Hindenburg son-in-law, who was a reserve officer and a legal expert, joined the staff to write a new legal code. Baltic Germans who owned vast estates feted Hindenburg and he hunted their game preserves.

Hindenburg would later judge German operations in 1915 to be "unsatisfactory". In his memoirs, he recounted that "[t]he Russian bear had escaped our clutches"[39] and abandoning the Polish salient had shortened their lines substantially. Conversely, victorious Falkenhayn believed that "The Russian Army has been so weakened by the blows it has suffered that Russia need not be seriously considered a danger in the foreseeable future".[40] The Russians replaced their experienced supreme commander, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, a man whose skill Hindenburg held in high regard,[41] with the incompetent Tsar.

1916

Brusilov Offensive

In the spring of 1916, the Central Powers experienced a military catastrophe in the East that left Germany bearing much of the war effort until the end of hostilities. On 4 June, the Russian Army began a massive offensive along 480 km (300 mi) of the southwestern front in present-day western Ukraine. In the ensuing onslaught, four armies commanded by General Aleksei Brusilov overwhelmed entrenchments that the Austro-Hungarians long regarded as impregnable.[42] Probing assault troops located three weak spots which then were struck in force. In nine days they captured more than 200,000 men and 200 guns, and pushed into open country.

Under Hindenburg's command, Ober Ost desperately shored up weak points with soldiers stripped from less threatened positions. Ludendorff was so distraught on the phone to OHL that General Wilhelm Groener (who directed the army's railroads and had been a competitor with Ludendorff on the General Staff) was sent to evaluate his nerves, which were judged satisfactory.[43] For a week the Russians kept attacking: they lost 80,000 men; the defenders 16,000. On 16 July the Russians attacked the German lines west of Riga but were ultimately thwarted. When looking back on the Russian offensive, Hindenburg admitted that another attack of such scale and ferocity would have left his forces "faced with the menace of a complete collapse." [44]

Commander of the Eastern Front

After having their strength decimated by the Russians in the Brusilov Offensive, the Austro-Hungarian forces submitted their Eastern Front forces to Hindenburg's command on 27 July (except for Archduke Karl's Army Group in southeast Galicia, in which General Hans von Seeckt was chief of staff). General von Eichhorn took over Army Group Hindenburg, while Hindenburg and Ludendorff, on a staff train equipped with the most advanced communication apparatus, visited their new forces. At threatened points they formed mixed German and Austro-Hungarian units while other Austro-Hungarian formations were bolstered by a sprinkling of German officers. Officers were exchanged between the German and Austro-Hungarian armies for training. The derelict citadel of the Brest Fortress was refurbished as their headquarters. Their front was almost 1,000 km (620 mi) and their only reserves were a cavalry brigade plus some artillery and machine gunners.[45]

Supreme Commander of the Central Powers

In the west, the Germans were hemorrhaging in the battles of Verdun and the Somme. Influential Army officers, led by the artillery expert Lieutenant Colonel Max Bauer, a friend of Ludendorff's, lobbied against Falkenhayn, deploring his futile steamroller at Verdun and his inflexible defense along the Somme, where he packed troops into the front-line to be battered by the hail of shells and sacked commanders who lost their front-line trench. German leaders contrasted Falkenhayn's bludgeon with Hindenburg's deft parrying.[46] The tipping point came when Falkenhayn ordered a spoiling attack by Bulgaria on Entente lines in Macedonia, which failed with heavy losses. Thus emboldened, Romania declared war on Austro-Hungary on 27 August, adding 650,000 trained enemies who invaded Hungarian Transylvania. Falkenhayn had been adamant that Romania would remain neutral. During the Kaiser's deliberations about who should command Falkenhayn said "Well, if the Herr Field Marshall has the desire and the courage to take the post". Hindenburg replied "The desire, no, but the courage—yes".[47] chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg favored Hindenburg, supposing him amenable to moderate peace terms,[48] mistaking his amiability as tractability and unaware that he was intent on enlarging Prussia.

Hindenburg was summoned to Pless on 29 August where he was named Chief of the Great General Staff and, by extension, the Supreme Army Command. Ludendorff demanded joint responsibility for all decisions";[49] Hindenburg did not demur. Henceforth, Ludendorff was entrusted with signing most orders, directives and the daily press reports. The eastern front was commanded by Leopold of Bavaria, with Hoffmann as his chief of staff. Hindenburg was also appointed the Supreme War Commander of the Central Powers, with nominal control over six million men. Until the end of the war, this arrangement formed the basis of Hindenburg's leadership which would come to be known as the Third OHL.

The British were unimpressed: General Charteris, Haig's intelligence chief, wrote to his wife "poor old Hindenburg is sixty-four years of age, and will not do very much."[50] Conversely, the German War Cabinet was impressed by his swift decision-making. They credited "Old Man Hindenburg" with ending the "Verdun folly" and setting in motion the "brilliant" conquest of Romania.[51]

Hindenburg and Ludendorff visited the Western Front in September, meeting the Army commanders and their staffs as well as their leaders: Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg and Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia. Both crown princes, with Prussian chiefs of staff, commanded Army Groups. Rupprecht and Albrecht were presented with field marshal's batons. Hindenburg told them that they must stand on the defensive until Romania was dealt with, meanwhile defensive tactics must be improved—ideas were welcome.[52] A backup defensive line, which the Entente called the Hindenburg Line, would be constructed immediately. Ludendorff promised more arms. Rupprecht was delighted that two such competent men had "replaced the dilettante 'Falkenhayn'."[53] Bauer was impressed that Hindenburg "saw everything only with the eye of the soldier."[54]

Bolstering defense

Under Field Marshal Hindenburg's leadership, the German Supreme Army Command issued a Textbook of Defensive Warfare that recommended fewer defenders in the front line relying on light machine guns. If pushed too hard, they were permitted to pull back. Front line defenses were organized so that penetrating enemy forces found themselves cut down by machine gun fire and artillery from those who knew the ranges and location of their own strong points. Subsequently, the infantry would counterattack while the attacker's artillery was blind because they were unsure where their own men were. A reserve division was positioned immediately behind the line, if it entered the battle it was commanded by the division whose position had been penetrated. (Mobile defense was also used in World War II.) Responsibilities were reassigned to implement the new tactics: front-line commanders took over reserves ordered into the battle and for flexibility infantry platoons were subdivided into eight man units under a noncom.

Field officers who visited headquarters often were invited to speak with Hindenburg, who inquired about their problems and recommendations. At this time he was especially curious about the eight man units,[55] which he regarded as "the greatest evidence of the confidence which we placed in the moral and mental powers of our army, down to its smallest unit."[56] Revised Infantry Field Regulations were published and taught to all ranks, including at a school for division commanders, where they maneuvered a practice division. A monthly periodical informed artillery officers about new developments. In the last months of 1916 the British battering along the Somme produced fewer German casualties. Overall, "In a fierce and obstinate conflict on the Somme, which lasted five months, the enemy pressed us back to a depth of about six miles on a stretch of nearly twenty-five miles"[57] Thirteen new divisions were created by reducing the number of men in infantry battalions, and divisions now had an artillery commander. Every regiment on the western front created an assault unit of storm troopers selected from their fittest and most aggressive men.[58] Lieutenant General Ernst von Höppner was given responsibility for both aerial and antiaircraft forces; the army's vulnerable zeppelins went to the navy. Most cavalry regiments were dismounted and the artillery received their badly needed horses.[59]

In October General Philippe Pétain began a series of limited attacks at Verdun, each starting with an intense bombardment coordinated by his artillery commander General Robert Nivelle. Then a double creeping barrage led the infantry into the shattered first German lines, where the attackers stopped to repel counterattacks.[60] With repeated nibbles by mid-December 1916 the French retook all the ground the Germans had paid for so dearly. Nivelle was given command of the French Army.

Headquarters routine

Hindenburg's day at OHL began at 09:00 when he and Ludendorff discussed the reports—usually quickly agreeing on what was to be done.[61] Ludendorff would give their staff of about 40 officers their assignments, while Hindenburg walked for an hour or so, thinking or chatting with guests. After conferring again with Ludendorff, he heard reports from his departmental heads, met with visitors and worked on correspondence. At noon Ludendorff gave the situation report to the Kaiser, unless an important decision was required when Hindenburg took over. He lunched with his personal staff, which included a son-in-law who was an Army officer. Dinner at 20:00 was with the general staff officers of all ranks and guests—crowned heads, allied leaders, politicians, industrialists and scientists. They left the table to subdivide into informal chatting groups.[62] At 21:30 Ludendorff announced that time was up and they returned to work. After a junior officer summarized the daily reports, he might confer with Ludendorff again before retiring.

The Hindenburg program

Under Hindenburg, the Third OHL set ambitious benchmarks for arms production in what became known as the Hindenburg Programme, which was directed from the War Office by General Groener. Major goals included a new light machine gun, updated artillery, and motor transport, but no tanks because they considered them too vulnerable to artillery. To increase output they needed skilled workers. The army released a million men.[63] For total war, the Supreme Army Command wanted all German men and women from 15 to 60 enrolled for national service. Hindenburg also wanted the universities closed, except for medical training, so that empty places would not be filled by women. To swell the next generation of soldiers he wanted contraceptives banned and bachelors taxed.[64] When a Polish army was being formed he wanted Jews excluded.[65] Few of these ideas were adopted, because their political maneuvering was vigorous but inept, as Admiral Müller of the Military Cabinet observed "Old Hindenburg, like Ludendorff, is no politician, and the latter is at the same time a hothead."[66] For example, women were not included in the service law that ultimately passed, because in fact more women were already seeking employment than there were openings.

The extent of his command

Following the death of Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Joseph on 21 November, Hindenburg met his successor Charles, who was frank about hoping to stop the fighting. Hindenburg's Eastern Front ran south from the Baltic to the Black Sea through what now are the Baltic States, Ukraine, and Romania. In Italy, the line ran from the Swiss border on the west to the Adriatic east of Venice. The Macedonian front extended along the Greek border from the Adriatic to the Aegean. The line contested by the Russians and Ottomans between the Black and Caspian Sea ran along the heights of the Caucasus mountains. Hindenburg urged the Ottomans to pull their men off the heights before winter but they did not. In his memoirs, he would later allege this was because of their "policy of massacre of the Armenians".[67] The front in Palestine ran from the Mediterranean to the southern end of the Dead Sea, and the defenders of Baghdad had a flank on the Tigris River. The Western Front ran southward from Belgium until near Laon, where it turned east to pass Verdun before again turning south to end at the Swiss Border. The remaining German enclaves in Africa were beyond his reach; an attempt to resupply them by dirigible failed. The Central Powers were surrounded and outnumbered.

1917

Arms buildup and unrestricted submarine warfare

By the second quarter of 1917, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were able to assemble 680,000 more men in 53 new divisions[68] and provide them with an adequate supply of new light machine guns. Field guns were increased from 5,300 to 6,700 and heavies from 3,700 to 4,340. They tried to foster fighting spirit by "patriotic instruction" with lectures and films[69] to "ensure that a fight is kept up against all agitators, croakers and weaklings".[70] Meanwhile, to mitigate the risk of being attacked before their buildup was complete, Germany's new military leadership waged unrestricted submarine warfare on allied shipping, which they claimed would defeat the British in six months. Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg and his allies expressed opposition to this policy, not wanting to bring the United States and other neutrals into the war. After securing the Dutch and Danish borders, Hindenburg announced that unrestricted submarine warfare was imperative and Ludendorff added his voice. On 9 January the chancellor was forced to bow to their unsound military judgments.

OHL moved west to the pleasant spa town of Bad Kreuznach in southwest Germany, which was on a main rail line. The Kaiser's quarters were in the spa building, staff offices were in the orange court, and the others lived in the hotel buildings. In February a third Army Group was formed on the Western Front to cover the front in Alsace-Lorraine, it was commanded by Archduke Albrecht of Württemberg. Some effective divisions from the east were exchanged for less competent divisions from the west. Since their disasters of the previous year the Russian infantry had shown no fight and in March the revolution erupted in Russia. Shunning opportunity, the Central Powers stayed put; Hindenburg feared that invaders would resurrect the heroic resistance of 1812.

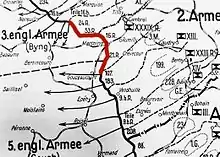

The great withdrawal and defending the Western Front

On the Western Front, the Third OHL deduced the German Army's huge salient between the valley of the Somme and Laon obviously was vulnerable to a pincer attack, which indeed the French were planning. The new Hindenburg line ran across its base. Subsequently, On 16 March, Hindenburg authorized Operation Alberich whereby German forces were ordered to move out all able-bodied inhabitants and portable possessions to new line running across the salient's base. In the process, they destroyed every building, leveled all roads and bridges, cut down every tree, fouled every well, and burned every combustible. In 39 days the Germans withdrew from a 1000 mi2 (2,590 km2) area, more ground than they had lost to all Allied offensives since 1914.[71] The cautiously following Allies also had to cope with booby traps, some exploding a month later. The new German front called the Hindenburg line was 42 km (26 mi) shorter freeing-up 14 German divisions.

On 9 April, the British attacked at Arras and overtook two German lines while occupying part of a third as the Canadians swept the Germans completely off the Vimy Ridge. When the excitable Ludendorff became distraught over such developments, Hindenburg reportedly calmed his First Quartermaster-General by "pressing his hand" and assuring him, "We have lived through more critical times than today together."[72] Ultimately, the British tried to exploit their opening with a futile cavalry charge but did not press further. In the battle's aftermath, the Third OHL discovered one reason behind the British attack's success was that the Sixth Army commander, Ludwig von Falkenhausen, had failed to properly apply their instructions for a defense in depth by keeping reserve troops too far back from the front lines.[73][74] As a result of this failure, Falkenhausen along with several staff officer were stripped of their command.[75]

The Eastern Front

After the Romanov dynasty's fall from power, Russia remained at war under the new revolutionary government led by Alexander Kerensky. In the Kerensky Offensive launched on July 1st, the Russian army pushed Austro-Hungarian forces in Galicia on 1 July. In order to counter this success, six German divisions mounted a counterattack on 18 July that tore a hole through the Russian front through which they sliced southward toward Tarnopol. The ensuing German advance threatened to encircle the Russian attackers, thereby causing them to retreat. At the end of August the advancing Central Powers stopped at the frontier of Moldavia. To keep up the pressure and to seize ground he intended to keep, Hindenburg shifted north to the heavily fortified city of Riga (today in Latvia) which has the broad Dvina River as a moat. On 1 September the Eighth Army, led by Oskar von Hutier, attacked; Bruchmüller's bombardment, which included gas and smoke shells, drove the defenders from the far bank east of the city, the Germans crossed in barges and then bridged the river, immediately pressing forward to the Baltic coast, pocketing the defenders of the Riga salient. Next a joint operation with the navy seized Oesel and two smaller islands in the Gulf of Riga. The Bolshevik revolution took Russia out of the war, an armistice was signed on 16 December.

The Reichstag peace resolution

Hindenburg detested Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg for dragging his feet about total and submarine warfare. Then in July the chancellor permitted the Reichstag to debate a resolution for peace without "annexations or indemnities". Colonel Bauer and the Crown Prince rushed to Berlin to block this peril. The minister of war urged Hindenburg and Ludendorff to join them, but when they arrived the Kaiser told them that "there could be no justification for their presence in Berlin". They should "return in haste to Headquarters where they certainly would be much better occupied."[76] They returned as ordered and then immediately telegraphed their resignations, which the Kaiser declined. The crisis was resolved when the monarchist parties voted no confidence in Bethmann-Hollweg, who resigned. Ludendorff and Bauer wanted to replace both the Kaiser and chancellor by a dictator, but Hindenburg would not agree.[77] Many historians believe that in fact Ludendorff assumed that role. The Reichstag passed a modified resolution calling for "conciliation" on 19 July, which the new chancellor Georg Michaelis agreed to "interpret".

The resolution became advantageous in August when Pope Benedict XV called for peace. The German response cited the resolution to finesse specific questions like those about the future of Belgium. The industrialists opposed Groener's advocacy of an excess profits tax and insistence that workers take a part in company management.[78][79] Ludendorff relieved Groener by telegram and sent him off to command a division.

Hindenburg's 70th birthday was celebrated lavishly all over Germany, 2 October was a public holiday, an honor that until then had been reserved only for the Kaiser.[80] Hindenburg published a birthday manifesto, which ended with the words:

With God's help our German strength has withstood the tremendous attack of our enemies, because we were one, because each gave his all gladly. So it must stay to the end. 'Now thank we all our God' on the bloody battlefield! Take no thought for what is to be after the war! This only brings despondency into our ranks and strengthens the hopes of the enemy. Trust that Germany will achieve what she needs to stand there safe for all time, trust that the German oak will be given air and light for its free growth. Muscles tensed, nerves steeled, eyes front! We see before us the aim: Germany honored, free and great! God will be with us to the end!"[81]

Victory in Italy

Bavarian mountain warfare expert von Dellmensingen was sent to assess the Austro-Hungarian defenses in Italy, which he found poor. Then he scouted for a site from which an attack could be mounted against the Italians. Hindenburg created a new Fourteenth Army with ten Austro-Hungarian and seven German divisions and enough airplanes to control the air, commanded by Otto von Below. The attackers slipped undetected into the mountains opposite to the opening of the Soča valley. The attack began during the night when the defender's trenches in the valley were abruptly shrouded in a dense cloud of poison gas released from 894 canisters fired simultaneously from simple mortars. The defenders fled before their masks would fail. The artillery opened fire several hours later, hitting the Italian reinforcements hastening up to fill the gap. The attackers swept over the almost empty defenses and marched through the pass, while mountain troops cleared the heights on either side. The Italians fled west, too fast to be cut off. Entente divisions were rushed to Italy to stem the retreat by holding a line on the Piave River. Below's Army was dissolved and the German divisions returned to the Western Front, where in October Pétain had directed a successful limited objective attack in which six days of carefully planned bombardment left crater-free pathways for 68 tanks to lead the infantry forward on the Lassaux plateau south of Laon, which forced the Germans off of the entire ridge—the French Army had recovered.

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

In the negotiations with the Soviet Government, Hindenburg wanted to retain control of all Russian territory that the Central Powers occupied, with German grand dukes ruling Courland and Lithuania, as well as a large slice of Poland. Their Polish plan was opposed by Foreign Minister Richard von Kühlmann, who encouraged the Kaiser to listen to the views of Max Hoffmann, chief of staff on the Eastern Front. Hoffmann demurred but when ordered argued that it would be a mistake bring so many Slavs into Germany, when only a small slice of Poland was needed to improve defenses. Ludendorff was outraged that the Kaiser had consulted a subordinate, while Hindenburg complained that the Kaiser "disregards our opinion in a matter of vital importance."[82] The Kaiser backed off, but would not approve Ludendorff's order removing Hoffmann, who is not even mentioned in Hindenburg's memoir. When the Soviets refused the terms offered at Brest-Litovsk the Germans repudiated the armistice and in a week occupied the Baltic States, Belarus and Ukraine, which had signed the treaty as a separate entity. Now the Russians signed also. Hindenburg helped to force Kühlmann out in July 1918.

1918

In January more than half a million workers went on strike; among their demands was a peace without annexations. The strike collapsed when its leaders were arrested, the labor press suppressed, strikers in the reserve called for active duty, and seven great industrial concern taken under military control, which put their workers under martial law.[83] On 16 January Hindenburg demanded the replacement of Count von Valentini, the chief of the Civil Cabinet. The Kaiser bridled, responding "I do not need your parental advice",[84] but nonetheless fired his old friend. The Germans were unable to tender a plausible peace offer because OHL insisted on controlling Belgium and retaining the French coalfields. All of the Central Powers' cities were on the brink of starvation and their armies were on short rations. Hindenburg realized that "empty stomachs prejudiced all higher impulses and tended to make men indifferent."[85] He blamed his allies' hunger on poor organization and transportation, not realizing that the Germans would have enough to eat if they collected their harvest efficiently and rationed its distribution effectively.[86]

Opting for a decision in the west

German troops were in Finland, the Baltic States, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, much of Romania, the Crimea, and in a salient east of Ukraine extending east almost to the Volga and south into Georgia and Armenia. Hundreds of thousands of men were needed to hold and police these conquests. More Germans were in Macedonia and in Palestine, where the British were driving north; Falkenhayn was replaced by Otto Liman von Sanders, who had led the defense of Gallipoli. All Hindenburg required was that these fronts stand firm while the Germans won in the west, where now they outnumbered their opponents. He firmly believed that his opponents could be crushed by battlefield defeats regardless of their far superior resources.

Offensive tactics were tailored to the defense. Their opponents were adopting defense in depth. He would attack the British because they were less skillful than the French.[88] The crucial blow would be in Flanders, along the River Lys, where the line was held by the Portuguese Army. However, winter mud prevented action there until April. Consequently, their first attack, named Michael, was on the southern part of the British line, at a projecting British salient near Saint-Quentin. Schwerpunkts would hit on either side of the salient's apex to pocket its defenders, the V Corps, as an overwhelming display of German power.

Additional troops and skilled commanders, like von Hutier, were shifted from the east. Army Group von Gallwitz was formed in the west on 1 February. One quarter of the western divisions were designated for attack; to counter the elastic defense, during the winter each of them attended a four-week course on infiltration tactics.[89] Storm troops would slip through weak points in the front line and slice through the battle zone, bypassing strong points that would be mopped up by the mortars, flamethrowers, and manhandled field guns of the next wave. As always surprise was essential, so the artillery was slipped into attack positions at night, relying on camouflage for concealment; the British aerial photographers were allowed free rein before D-day. There would be no preliminary registration fire; the gunners were trained for map firing in schools established by Bruchmüller. In the short, intense bombardment each gun fired in a precise sequence, shifting back and forth between different targets, using many gas shells to keep defenders immersed in a toxic cloud. On D-day, the air force would establish air supremacy and strafe enemy strong points, and also update commanders on how far the attackers had penetrated. Signal lamps were used for messaging on the ground. Headquarters moved close to the front and as soon as possible would advance to pre-selected positions in newly occupied ground. OHL moved to Spa, Belgium while Hindenburg and Ludendorff were closer to the attack at Avesnes, France, which re-awoke his memories of occupied France 41 years before.[90]

Breaking the trench stalemate

Operation Michael began on 21 March. The first day's reports were inconclusive, but by day two the Germans knew they had broken through some of the enemy artillery lines. But the encirclement failed because British stoutness gave their V Corps time to slip out of the targeted salient. On day four, German forces moved on into open country, and the Kaiser prematurely celebrated by awarding Hindenburg the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross, a medal first created for von Blücher.[91] As usual, Hindenburg set objectives as the situation evolved. South of the salient, the Germans had almost destroyed the British Fifth Army, so they pushed west to cut between the French and British armies. However, they advanced too slowly through the broken terrain of the former Somme battlefields and the ground devastated when withdrawing the year before, and because troops stopped to loot food and clothing, and the Allies maintained a fluid defensive line, manned by troops brought up and supplied by rail and motor transport. Hindenburg hoped the Germans would to get close enough to Amiens to bombard the railways with heavy artillery, but they were stopped just short, after having advanced a maximum of 65 km (40 mi). Hindenburg also hoped that civilian morale would crumble, because Paris was being shelled by naval guns mounted on rail carriages 120 km (75 mi) away, but he underestimated French resiliency.

The Allied command was dismayed. French headquarters realized: "This much became clear from the terrible adventure, that our enemies were masters of a new method of warfare. ... What was even more serious was that it was perceived that the enemy's power was due to a thing that cannot be improvised, the training of officers and men."[92]

Prolonging Michael with the drive west delayed and weakened the attack in Flanders. Again the Germans broke through, smashing the Portuguese defenders and forcing the British from all of the ground they had paid so dearly for in 1917. However, French support enabled the British to save Hazebrouck, the rail junction that was the German goal. To draw the French reserves away from Flanders, the next attack was along the Aisne River where Nivelle had attacked the year before. Their success was dazzling. The defender's front was immersed in a gas cloud fired from simple mortars.[93] Within hours the Germans had reoccupied all the ground the French had taken by weeks of grinding, and they swept south through Champagne until they halted for resupply at the Marne River.

However, the Germans had lost 977,555 of their best men between March and the end of July, while Allied ranks were swelling with Americans. Their dwindling stock of horses were on the verge of starvation, and the ragged troops thought continually of food. One of the most effective propaganda handbills, which the British showered on the German lines, listed the rations received by prisoners of war. The German troops resented their officers' better rations and reports of the ample meals at headquarters; in his memoirs, Ludendorff devotes six pages to defending officer's rations and perks.[94] After an attack, the survivors needed at least six weeks to recuperate, but now crack divisions were recommitted much sooner. Tens of thousands of men were skulking behind the lines. Determined to win, Hindenburg decided to expand the salient pointing toward Paris to strip more defenders from Flanders. The attack on Gouraud's French Fourth Army followed the now familiar scenario, but was met by a deceptive elastic defense and was decisively repelled at the French main line of resistance.[95] Hindenburg still intended to make a decisive attack in Flanders, but before the Germans could strike, the French and Americans, led by light tanks, smashed through the right flank of the German salient on the Marne. The German defense was halfhearted; they had lost. Hindenburg went on the defensive. The Germans withdrew one by one from the salients created by their victories, evacuating the wounded and supplies, and retiring to shortened lines. Hindenburg hoped to hold a line until their enemies were ready to bargain.

Ludendorff's breakdown

After the retreat from the Marne, Ludendorff became distraught, shrieking orders and often in tears. At dinner on 19 July, he responded to a suggestion of Hindenburg's by shouting "I have already told you that is impossible"—Hindenburg led him from the room.[96] On 8 August, the British completely surprised the Germans with a well-coordinated attack at Amiens, breaking well into the German lines. Most disquieting was that some German commanders surrendered their units and that reserves arriving at the front were taunted for prolonging the war. For Ludendorff, Amiens was the "black day in the history of the German Army."[97] Bauer and others wanted Ludendorff replaced, but Hindenburg stuck by his friend; he knew that "Many a time has the soldier's calling exhausted strong characters."[98] A sympathetic physician who was Ludendorff's friend persuaded him to leave headquarters temporarily to recuperate. (His breakdown is not mentioned in Hindenburg's or Ludendorff's memoirs.) On 12 August, Army Group von Boehn was created to firm up the defenses in the Somme sector. On 29 September Hindenburg and Ludendorff told the incredulous Kaiser that the war was lost and that they must have an immediate armistice.

Defeat and revolution

A new chancellor, Prince Maximilian of Baden, opened negotiations with President Woodrow Wilson, who would deal only with a democratic Germany. Prince Max told the Kaiser that he would resign unless Ludendorff was dismissed, but that Hindenburg was indispensable to hold the army together. On 26 October the Kaiser slated Ludendorff before curtly accepting his resignation—then rejecting Hindenburg's. Afterwards, Ludendorff refused to share Hindenburg's limousine.[99] Colonel Bauer was retired. Hindenburg promptly replaced Ludendorff with Groener, the chief of staff of Army Group Kiev, which was assisting a breakaway Ukrainian State to fend off the Bolsheviks while receiving food and oil.

The Germans were losing their allies. In June the Austro-Hungarians in Italy attacked the Entente lines along the Piave River but were repelled decisively. On 24 October the Italians crossed the river in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. After a few days of resolute resistance the defense collapsed, weakened by the defection of men from the empire's subject nations and by starvation: the men in their Sixth Army had an average weight of 120 lb (54 kg).[100] On 14 October, Austria-Hungary asked for an armistice in Italy, but the fighting went on. In September the Entente and their Greek allies attacked in Macedonia. The Bulgarians begged for more Germans to stiffen their troops, but Hindenburg had none to spare. Many Bulgarian soldiers deserted as they retreated toward home, opening the road to Constantinople. The Austro-Hungarians were pushed back in Serbia, Albania and Montenegro, and signed an armistice on 3 November. The Ottomans were overextended, trying to defend Syria while exploiting the Russian collapse to move into the Caucasus, despite Hindenburg's urging them to defend what they had. The British and Arabs broke through in September, capturing Damascus. The Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October.

Wilson insisted that the Kaiser must go, but he refused to abdicate. Wilhelm was determined to lead the Army home to suppress the growing rebellion. It had had started with large demonstrations in major cities. When the Navy ordered a final sortie against the British, mutineers took control of the fleet. Workers' and soldiers' councils spread rapidly throughout Germany. They stripped officers of their badges of rank and decorations, if necessary forcibly. On 8 November, Hindenburg and the Kaiser met with 39 regimental officers at Spa. There he delivered a situation report and answered questions.[101] Then Hindenburg left and Groener asked the officers to answer confidentially two questions about whether their troops would follow the Kaiser. The answers were decisive: the army would not. The Kaiser gave in. This was superfluous, because in Berlin Prince Max had already publicly announced the Kaiser's abdication and his own resignation, and that the Social Democrat leader Friedrich Ebert was now chancellor. Democracy came abruptly and almost bloodlessly. That evening Groener telephoned Ebert, who he knew and trusted, to tell him that if the new government would fight Bolshevism and support the Army then the field marshal would lead a disciplined army home.[102] Hindenburg's remaining in command bolstered the new government's position.

The withdrawal became more fraught when the armistice obliged all German troops to leave Belgium, France, and Alsace-Lorraine in 14 days and to be behind the Rhine in 30 days. Stragglers would become prisoners. When the seven men from the executive committee of the soldiers' council formed at Spa arrived at OHL they were greeted politely by a lieutenant colonel, who acknowledged their leadership. When they broached the march home he took them to the map room, explaining allocation of roads, and scheduling unit departures, billeting, and feeding. They agreed that the existing staffs should make these arrangements.[103] To oversee the withdrawals OHL transferred headquarters from Belgium to Kassel in Germany, unsure how their officers would be received by the revolutionaries. They were greeted by the chairman of the workers' and soldiers' councils who proclaimed "Hindenburg belongs to the German nation."[104] His staff intended to billet him in the Kaiser's palace there, Wilhelmshöhe. Hindenburg refused because they did not have the Kaiser's permission, instead settling into a humble inn, thereby pleasing both his monarchist staff and the revolutionary masses. In the west 1.25 million men and 500,000 horses were brought home in the time allotted.[105]

Hindenburg did not want to involve the Army in the defense of the new government against their civil enemies. Instead the Army supported the independent Freikorps (modeled on formations used in the Napoleonic wars), supplying them with weapons and equipment. In February 1919, OHL moved east to Kolberg to mount an offensive against impinging Soviet troops, but they were restrained by the Allied occupation administration, which in May 1919 ordered all German troops in the east home. On 25 June 1919, Hindenburg retired to Hanover once again. He settled in a splendid new villa, which was a gift of the city, despite his admittedly having "lost the greatest war in history".[106]

Military reputation

"Victory comes from movement" was Schlieffen's principle for war.[107] His disciple Hindenburg expounded his ideas as an instructor of tactics and then applied them on World War I battlefields: his retreats and mobile defenses were as skillful and daring as his slashing Schwerpunkt attacks, which even broke through the trench barrier on the Western Front. He failed to win because once through they were too slow—legs could not move quite fast enough. (With engines, German movement overwhelmed western Europe in World War II.)

Surprisingly, Hindenburg has undergone a historical metamorphosis: his teaching of tactics and years on the General Staff forgotten while he is remembered as a commander as an appendage to Ludendorff's genius. Winston Churchill in his influential history of the war, published in 1923, depicts Hindenburg as a figurehead awed by the mystique of the General Staff, concluding that "Ludendorff throughout appears as the uncontested master."[108] Churchill led the way: later he is Parkinson's "beloved figurehead",[109] while to Stallings he is "an old military booby".[110] These distortions stemmed from Ludendorff, who strutted in the limelight during the war and immediately thereafter wrote his comprehensive memoir with himself center stage.[111] Hindenburg's far less detailed memoir never disputed his valued colleague's claims, military decisions were made by "we" not "I", and it is less useful to historians because it was written for general readers.[112] Ludendorff continued touting his preeminence in print,[113] which, typically, Hindenburg never disputed publicly.

Others did. The OHL officers who testified before the Reichstag committee investigating the collapse of 1918 agreed that Hindenburg was always in command.[114][115][116] He managed by setting objectives and appointing talented men to do their jobs, for instance "giving full scope to the intellectual powers" of Ludendorff.[117] Naturally these subordinates often felt that he did little, even though he was setting the course. In addition Ludendorff overrated himself, repressing repeated demonstrations that he lacked the backbone essential to command.[118] Postwar he displayed extraordinarily poor judgment and a penchant for bizarre ideas, contrasting sharply with his former commander's surefooted adaptations to changing times.

Most of their conferences were in private, but on 26 July 1918 the chief of staff of the Seventh Army, Fritz von Lossberg traveled to OHL to request permission to withdraw to a better position [119]

Without knocking I entered Ludendorff's office and found him loudly arguing with the field marshal. I assumed it was over the situation at the Seventh Army. In any case as soon as I entered the field marshall asked me to give my assessment of the situation at the Seventh Army. I described it in short terms and emphasized especially that based on my own observations I thought the condition of the troops was cause for serious concern. For the past few days the Seventh Army commanding general, the staff, and I had all been recommending a withdrawal from the increasingly untenable front lines. I told Hindenburg that I had come to Avesenes with the concurrence of the Seventh Army commanding general to secure such an order. The field marshall turned to Ludendorff, saying something to the effect of 'Now Ludendorff, make sure that the order goes out immediately. ' He then left Ludendorff's office rather upset.

— Lossberg

Hindenburg's record as a commander starting in the field at Tannenberg, then leading four national armies, culminating with breaking the trench deadlock in the west, and then holding his defeated army together, is unmatched by any other soldier in World War I.

However, military skill should not mask the other component of their record: "... in general, the maladroit politics of Hindenburg and Ludendorff led directly to the collapse of 1918...."[120]

In the Republic

The new republic held its first election on 19 January 1919. Parties representing a broad range of different constituencies ran candidates and voting was with proportional representation, so inevitably governments were formed by coalitions of parties: this time Social Democrats, Democrats, and Centrists. Ebert was elected as provisional chancellor; then the elected representatives assembled in Weimar to write a constitution. It was based on the Constitution of the German Empire written in 1871, with many of the Kaiser's powers now given to a president elected for a term of seven years. The president selected the chancellor and the members of the cabinet, but with the crucial stipulation that his nominees had to be ratified by the Reichstag, which because of proportional representation required support from several parties. The constitution was adopted on 11 August 1919. Ebert was elected as provisional president.

The terms of the Treaty of Versailles were written in secret. It was unveiled on 7 May 1919 and was followed by an ultimatum: either ratify the treaty, or the Allies would take whatever measures they deemed necessary to enforce its terms. While Germans of all political shades cursed the treaty as an insult to the nation's honor, President Ebert was sober enough to consider the possibility that Germany would not be in a position to turn it down. To save face, he asked Hindenburg whether the army was prepared to defend against an Allied invasion from the west, which Ebert believed would be all but certain if the treaty were voted down. If there was even the slightest chance that the army could hold out, he promised to urge rejection of the treaty. Under some prodding from his chief of staff, Groener, Hindenburg concluded the army could not resume the war under any circumstances. Rather than tell Ebert himself, he directed Groener to deliver the army's recommendation to the president.[121] With just 19 minutes to spare, Ebert informed French Premier Georges Clemenceau that Germany would ratify the Treaty, which was signed on 28 June 1919.

Second retirement

Back in Hanover, as a field marshal he was provided with a staff who helped with his still extensive correspondence. He made few formal public appearances, but the streets around his house often were crowded with admirers when he took his afternoon walk. During the war he had left the newspaper reporters to Ludendorff, now he was available. He hunted locally and elsewhere, including an annual chamois hunt in Bavaria. The yearly Tannenberg memorial celebration kept him in the public eye.

A Berlin publisher urged him to produce his memoirs which could educate and inspire by emphasizing his ethical and spiritual values; his story and ideas could be put on paper by a team of anonymous collaborators and the book would be translated immediately for the worldwide market.[122] Mein Leben ('My Life') was a huge bestseller, presenting to the world his carefully crafted image as a staunch, steadfast, uncomplicated soldier. Major themes were the need for Germany to maintain a strong military as the school teaching young German men moral values and the need to restore the monarchy, because only under the leadership of the House of Hohenzollern could Germany become great again, with "The conviction that the subordination of the individual to the good of the community was not only a necessity, but a positive blessing ...".[123] Throughout the Kaiser is treated with great respect. He concealed his cultural interests and assured his readers: "It was against my inclination to take any interest in current politics."[124] (Despite what his intimates knew of his "deep knowledge of Prussian political life".[125]) Mein Leben was dismissed by many military historians and critics as a boring apologia that skipped over the controversial issues, but it painted for the German public precisely the image he sought.

The Treaty required the German army to have no more than 100,000 men and abolished the General Staff. Therefore, in March 1919 The Reichswehr was organized. The 430,000 armed men in Germany competed for the limited places.[126] Both Major Oskar Hindenburg and his army officer brother-in-law were selected. The chief of staff was Seeckt, camouflaged as Chief of the Troop Office. He favored staff officers above line officers and the proportion of nobles was the same as prewar.

In 1919, Hindenburg was subpoenaed to appear before the parliamentary commission investigating the responsibility for the outbreak of war in 1914 and for the defeat in 1918.[127] He was wary, as he had written: "The only existing idol of the nation, undeservedly my humble self, runs the risk of being torn from its pedestal once it becomes the target of criticism.".[128] Ludendorff was summoned also. They had been strangers since Ludendorff's dismissal, but they prepared and arrived together on 18 November 1919. Hindenburg refused to take the oath until Ludendorff was permitted to read a statement that they were under no obligation to testify since their answers might expose them to criminal prosecution, but they were waiving their right of refusal. On the stand Hindenburg read through a prepared statement, ignoring the chairman's repeated demands that he answer questions. He testified that the German Army had been on the verge of winning the war in the autumn of 1918 and that the defeat had been precipitated by a Dolchstoß ("stab in the back") by disloyal elements on the home front and unpatriotic politicians, quoting a dinner conversation he had Sir Neill Malcolm. When his reading was finished Hindenburg walked out of the hearings, despite being threatened with contempt, sure that they would not dare charge a war hero. His testimony introduced the Dolchstoßlegende, which was adopted by nationalist and conservative politicians who sought to blame the socialist founders of the Weimar Republic for losing the war. Reviews in the German press that grossly misrepresented General Frederick Maurice's book about the last months of the war firmed-up this myth.[129] Ludendorff had used these reviews to convince Hindenburg.[130] A 1929 film glorifying his life as a dedicated patriot solidified his image.[131]

The first presidential election was scheduled for 6 June 1920. Hindenburg wrote to Wilhelm II, in exile in the Netherlands, for permission to run.[132] Wilhelm approved, so on 8 March Hindenburg announced his intention to seek the presidency. Five days later Berlin was seized by regular and Freikorps troops led by General Lüttwitz, the commander of the Berlin garrison, who proclaimed a prominent civil servant, Wolfgang Kapp, president in a new government. Ludendorff and Colonel Bauer stood by Kapp's side. As the Reichswehr leadership refused to fight the coup, the legal government fled to Stuttgart. However the coup collapsed after six days as the civil service refused to cooperate and workers went on a general strike. The strike led to a Bolshevik uprising that was put down forcefully. Kapp died in prison while awaiting trial, Ludendorff fled to Bavaria where he was shielded by his fame, Bauer went into exile. The Reichstag postponed the presidential election and extended Ebert's term of office. Hindenburg cut back on public appearances.[133]

His serenity was shattered by the illness of his wife Gertrud, who died of cancer on 14 May 1921. He kept close to his three children, their spouses and his nine grandchildren. His son Oskar was at his side as the field marshal's liaison officer. Hindenburg was financially sustained by a fund set up by a group of admiring industrialists.[134]

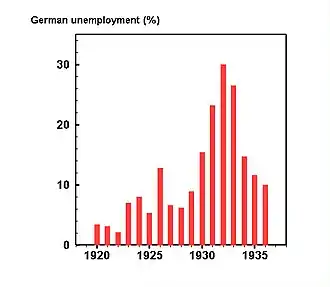

On 8 November 1923 Hitler, with Ludendorff at his side, launched the Beer Hall Putsch in Munich, which was suppressed by the Bavarian police. Hindenburg was not involved but inevitably was prominent in newspaper reports. He issued a statement urging national unity.[135] On 16 November the Reichsbank introduced the Rentenmark, which was indexed to gold bonds. Twelve zeros were cut from prices, which stabilized. The political divisions in the nation began to ease. The foreign minister was Gustav Stresemann, the leader of the German People's Party. In 1924 the economy was shored up by the reduction in reparation payments in the Dawes Plan with loans from American banks. At Tannenberg in August before a crowd of 50,000 Hindenburg laid the headstone for an imposing memorial.

1925 election

Reichspräsident Ebert died on 28 February 1925 following an appendectomy. A new election had to be held within a month. None of the candidates attained the required majority; Ludendorff was last with a paltry 280,000 votes. By law there had to be another election. The Social Democrats, the Catholic Centre and other democratic parties united to support the centre's Wilhelm Marx, who had twice served as chancellor and was now Minister President of Prussia. The Communists insisted on running their own candidate. The parties on the right established a committee to select their strongest candidate. After a week's indecision they decided on Hindenburg, despite his advanced age and fear, notably by Foreign Minister Stresemann, of unfavorable reactions by their former enemies. A delegation came to his home on 1 April. He stated his reservations but concluded "If you feel that my election is necessary for the sake of the Fatherland, I'll run in God's name."[136] However, some parties on the right still opposed him. Not willing to be humiliated like Ludendorff, he drafted a telegram declining the nomination, but before it was sent, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz and a young leader of the agrarian nobility of eastern Germany arrived in Hanover to persuade him to wait until the strength of his support was clearer. His conservative opponents gave way so he consented on 9 April. Again he obtained Wilhelm II's approval. His campaign stressed his devotion to "social justice, religious equality, genuine peace at home and abroad."[137] "No war, no internal uprising, can emancipate our chained nation, which is, unfortunately, split by dissension." He addressed only one public meeting, held in Hanover, and gave one radio address on 11 April calling for a Volksgemeinschaft (national community) under his leadership.[138] The second election, held on 26 April 1925, required only a plurality, which he obtained thanks to the support of the Bavarian People's Party (BVP), which had switched from Marx, and by the refusal of the Communists to withdraw their candidate Ernst Thälmann.[139] In the UK and France, the victory of the aged field marshal was accepted with equanimity.[140][141]

Parliamentary governments

Hindenburg took office on 12 May 1925, "... offering my hand in this hour to every German".[142] He moved into the elegant Presidential Palace on the Wilhelmstrasse, accompanied by Oskar (his military liaison officer) and Oskar's wife and three children. The new president, always a stickler about uniforms, soon had the servants wear new regalia with the shoe buckles appropriate for a court.[143] Nearby was the chancellery, which during Hindenburg's tenure would have seven residents. The president also enjoyed a shooting preserve. He notified Chancellor Hans Luther that he would replace the head of Ebert's presidential staff, Dr Otto Meissner, with his own man, because the cabinet would have to consent. Meissner was kept on temporarily. He proved invaluable and was Hindenburg's right hand throughout his presidency.

Foreign Minister Stresemann had vacationed during the campaign so as not to tarnish his reputation with the victors by supporting the field marshal. The far right detested Stresemann for promoting friendly relations with the victors. At their first meeting Hindenburg listened attentively and was persuaded that Stresemann's strategy was correct.[144] He was cooler at their next, reacting to rightist backlash.[145] Nonetheless, he supported the government's policy, so on 1 December 1925 the Locarno Treaties were signed, a significant step in restoring Germany's position in Europe. The right was infuriated because the Treaty accepted the loss of Alsace and Lorraine, though it mandated the withdrawal of the Allied troops occupying the Rhineland. The president always was lobbied intensely by visitors and letter writers. Hindenburg countered demands to restore the monarchy by arguing that restoring a Hohenzollern would block progress in revising Versailles.[146] He accepted the republic as the mechanism for restoring Germany's position in Europe, though Hindenburg was no Vernunftrepublikaner (republican by reason) because democracy was incompatible with the militaristic volksgemeinschaft (national community) that would unite the people into one for future conflicts.[147]