Cameroon

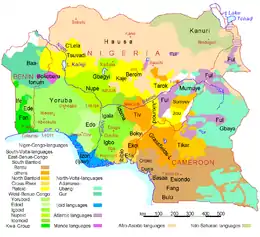

Cameroon (/ˌkæməˈruːn/ (![]() listen); French: Cameroun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (French: République du Cameroun), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the Central African Republic to the east; and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo to the south. Its coastline lies on the Bight of Biafra, part of the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean. Due to its strategic position at the crossroads between West Africa and Central Africa, it has been categorized as being in both camps. Its nearly 27 million people speak 250 native languages.[7][8][9]

listen); French: Cameroun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (French: République du Cameroun), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the Central African Republic to the east; and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo to the south. Its coastline lies on the Bight of Biafra, part of the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean. Due to its strategic position at the crossroads between West Africa and Central Africa, it has been categorized as being in both camps. Its nearly 27 million people speak 250 native languages.[7][8][9]

Republic of Cameroon | |

|---|---|

Flag

Coat of arms

| |

| Motto: "Paix – Travail – Patrie" (French) "Peace – Work – Fatherland" | |

| Anthem: "Ô Cameroun, Berceau de nos Ancêtres" (French) "O Cameroon, Cradle of Our Forefathers" | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital | Yaoundé[1] 3°52′N 11°31′E |

| Largest city | Douala |

| Official languages | French • English |

| Recognised regional languages |

|

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion (2020)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Cameroonian |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party presidential republic[3] |

• President | Paul Biya |

• Prime Minister | Joseph Ngute |

• President of Senate | Marcel Niat Njifenji |

• president of House | Cavayé Yéguié Djibril |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| National Assembly | |

| Independence from France and the United Kingdom | |

• Independence from France | 1 January 1960 |

• Independence from the United Kingdom | 1 October 1961 |

| Area | |

• Total | 475,442 km2 (183,569 sq mi) (53rd) |

• Water (%) | 0.57 [1] |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 29,321,637 [1] (51st) |

• Density | 39.7/km2 (102.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2021 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2021 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2014) | 46.6[5] high |

| HDI (2019) | medium · 153rd |

| Currency | Central African CFA franc (XAF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy yyyy/mm/dd |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +237 |

| ISO 3166 code | CM |

| Internet TLD | .cm |

| |

Early inhabitants of the territory included the Sao civilisation around Lake Chad, and the Baka hunter-gatherers in the southeastern rainforest. Portuguese explorers reached the coast in the 15th century and named the area Rio dos Camarões (Shrimp River), which became Cameroon in English. Fulani soldiers founded the Adamawa Emirate in the north in the 19th century, and various ethnic groups of the west and northwest established powerful chiefdoms and fondoms. Cameroon became a German colony in 1884 known as Kamerun. After World War I, it was divided between France and the United Kingdom as League of Nations mandates. The Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) political party advocated independence, but was outlawed by France in the 1950s, leading to the national liberation insurgency fought between French and UPC militant forces until early 1971. In 1960, the French-administered part of Cameroon became independent, as the Republic of Cameroun, under President Ahmadou Ahidjo. The southern part of British Cameroons federated with it in 1961 to form the Federal Republic of Cameroon. The federation was abandoned in 1972. The country was renamed the United Republic of Cameroon in 1972 and back to the Republic of Cameroon in 1984 by a presidential decree by president Paul Biya. Paul Biya, the incumbent president, has led the country since 1982 following Ahidjo's resignation; he previously held office as prime minister from 1975 on. Cameroon is governed as a Unitary Presidential Republic.

The official languages of Cameroon are French and English, the official languages of former French Cameroons and British Cameroons. Its religious population is predominantly Christian, with a significant minority practicing Islam, and others following traditional faiths. It has experienced tensions from the English-speaking territories, where politicians have advocated for greater decentralisation and even complete separation or independence (as in the Southern Cameroons National Council). In 2017, tensions over the creation of an Ambazonian state in the English-speaking territories escalated into open warfare.

Large numbers of Cameroonians live as subsistence farmers. The country is often referred to as "Africa in miniature" for its geological, linguistic and cultural diversity.[10][7] Its natural features include beaches, deserts, mountains, rainforests, and savannas. Its highest point, at almost 4,100 metres (13,500 ft), is Mount Cameroon in the Southwest Region. Its most populous cities are Douala on the Wouri River, its economic capital and main seaport; Yaounde, its political capital; and Garoua. Limbe in the Southwest has a natural seaport. Cameroon is well known for its native music styles, particularly Makossa, Njang and Bikutsi, and for its successful national football team. It is a member state of the African Union, the United Nations, the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), the Commonwealth of Nations, Non-Aligned Movement and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.

Etymology

Originally, Cameroon was the exonym given by the Portuguese to the Wouri River, which they called Rio dos Camarões meaning "river of shrimps" or "shrimp river", referring to the then abundant Cameroon ghost shrimp.[11][12] Today the country's name in Portuguese remains Camarões.

History

Early history

Present-day Cameroon was first settled in the Neolithic Era. The longest continuous inhabitants are groups such as the Baka (Pygmies).[13] From there, Bantu migrations into eastern, southern and central Africa are believed to have occurred about 2,000 years ago.[14] The Sao culture arose around Lake Chad, c. 500 AD, and gave way to the Kanem and its successor state, the Bornu Empire. Kingdoms, fondoms, and chiefdoms arose in the west.[15]

Portuguese sailors reached the coast in 1472. They noted an abundance of the ghost shrimp Lepidophthalmus turneranus in the Wouri River and named it Rio dos Camarões (Shrimp River), which became Cameroon in English.[16] Over the following few centuries, European interests regularised trade with the coastal peoples, and Christian missionaries pushed inland.[17]

The Ottoman wars in Africa began at the end of the 16th century. Born in Logone-Birni, Cameroon, Abram Petrovich Gannibal (c. 1696 – 14 May 1781[1]), Russian military engineer, general-in-chief, and nobleman, was kidnapped as a child by Ottomans, traded, presented to Peter the Great, who freed him, adopted and raised him as his godson. His descendants entered the Russian nobility. One of them was Russia's national poet Alexander Pushkin.

In the early 19th century, Modibo Adama led Fulani soldiers on a jihad in the north against non-Muslim and partially Muslim peoples and established the Adamawa Emirate. Settled peoples who fled the Fulani caused a major redistribution of population.

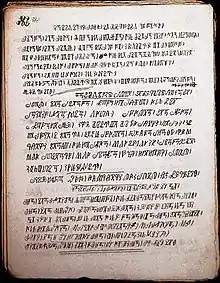

In 1896, Sultan Ibrahim Njoya created the Bamum script, or Shu Mom, for the Bamum language.[18][19] It is taught in Cameroon today by the Bamum Scripts and Archives Project.[19]

German rule

Germany began to establish roots in Cameroon in 1868 when the Woermann Company of Hamburg built a warehouse. It was built on the estuary of the Wouri River. Later Gustav Nachtigal made a treaty with one of the local kings to annex the region for the German emperor.[20] The German Empire claimed the territory as the colony of Kamerun in 1884 and began a steady push inland; the natives resisted. Under the aegis of Germany commercial companies were local administrations. These concessions used forced labour to run profitable banana, rubber, palm oil, and cocoa plantations.[20] Even infrastructure projects relied on forced labor regimen. This economic policy was much criticised by the other colonial powers.[21]

French and British rule

With the defeat of Germany in World War I, Kamerun became a League of Nations mandate territory and was split into French Cameroon (French: Cameroun) and British Cameroon in 1919. France integrated the economy of Cameroon with that of France[22] and improved the infrastructure with capital investments and skilled workers, modifying the colonial system of forced labour.[21]

The British administered their territory from neighbouring Nigeria. Natives complained that this made them a neglected "colony of a colony". Nigerian migrant workers flocked to Southern Cameroons, ending forced labour altogether but angering the local natives, who felt swamped.[23] The League of Nations mandates were converted into United Nations Trusteeships in 1946, and the question of independence became a pressing issue in French Cameroon.[22]

France outlawed the pro-independence political party, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (Union des Populations du Cameroun; UPC), on 13 July 1955.[24] This prompted a long guerrilla war waged by the UPC and the assassination of several of the party's leaders, including Ruben Um Nyobè, Félix-Roland Moumié and Ernest Ouandie. In the British Cameroons, the question was whether to reunify with French Cameroon or join Nigeria; the British ruled out the option of independence.[25]

Independence

On 1 January 1960, French Cameroun gained independence from France under President Ahmadou Ahidjo. On 1 October 1961, the formerly British Southern Cameroons gained independence from the United Kingdom by vote of the UN General Assembly and joined with French Cameroun to form the Federal Republic of Cameroon, a date which is now observed as Unification Day, a public holiday.[26] Ahidjo used the ongoing war with the UPC to concentrate power in the presidency, continuing with this even after the suppression of the UPC in 1971.[27]

His political party, the Cameroon National Union (CNU), became the sole legal political party on 1 September 1966 and on 20 May 1972, a referendum was passed to abolish the federal system of government in favour of a United Republic of Cameroon, headed from Yaoundé.[28] This day is now the country's National Day, a public holiday.[29] Ahidjo pursued an economic policy of planned liberalism, prioritising cash crops and petroleum development. The government used oil money to create a national cash reserve, pay farmers, and finance major development projects; however, many initiatives failed when Ahidjo appointed unqualified allies to direct them.[30]

The national flag was changed on 20 May 1975. Two stars were removed, replaced with a large central star as a symbol of national unity.

Ahidjo stepped down on 4 November 1982 and left power to his constitutional successor, Paul Biya. However, Ahidjo remained in control of the CNU and tried to run the country from behind the scenes until Biya and his allies pressured him into resigning. Biya began his administration by moving toward a more democratic government, but a failed coup d'état nudged him toward the leadership style of his predecessor.[31]

An economic crisis took effect in the mid-1980s to late 1990s as a result of international economic conditions, drought, falling petroleum prices, and years of corruption, mismanagement, and cronyism. Cameroon turned to foreign aid, cut government spending, and privatised industries. With the reintroduction of multi-party politics in December 1990, the former British Southern Cameroons pressure groups called for greater autonomy, and the Southern Cameroons National Council advocated complete secession as the Republic of Ambazonia.[32] The 1992 Labour Code of Cameroon gives workers the freedom to belong to a trade union or not to belong to any trade union at all. It is the choice of a worker to join any trade union in his occupation since there are more than one trade union in each occupation.[33]

In June 2006, talks concerning a territorial dispute over the Bakassi peninsula were resolved. The talks involved President Paul Biya of Cameroon, then President Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria and then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, and resulted in Cameroonian control of the oil-rich peninsula. The northern portion of the territory was formally handed over to the Cameroonian government in August 2006, and the remainder of the peninsula was left to Cameroon 2 years later, in 2008.[34] The boundary change triggered a local separatist insurgency, as many Bakassians refused to accept Cameroonian rule. While most militants laid down their arms in November 2009,[35] some carried on fighting for years.[36]

In February 2008, Cameroon experienced its worst violence in 15 years when a transport union strike in Douala escalated into violent protests in 31 municipal areas.[37][38]

In May 2014, in the wake of the Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping, presidents Paul Biya of Cameroon and Idriss Déby of Chad announced they were waging war on Boko Haram, and deployed troops to the Nigerian border.[39] Boko Haram launched several attacks into Cameroon, killing 84 civilians in a December 2014 raid, but suffering a heavy defeat in a raid in January 2015. Cameroon declared victory over Boko Haram on Cameroonian territory in September 2018.[40]

Since November 2016, protesters from the predominantly English-speaking Northwest and Southwest regions of the country have been campaigning for continued use of the English language in schools and courts. People were killed and hundreds jailed as a result of these protests.[41] In 2017, Biya's government blocked the regions' access to the Internet for three months.[42] In September, separatists started a guerilla war for the independence of the Anglophone region as the Federal Republic of Ambazonia. The government responded with a military offensive, and the insurgency spread across the Northwest and Southwest regions. As of 2019, fighting between separatist guerillas and government forces continues.[43] During 2020, numerous terrorist attacks—many of them carried out without claims of credit—and government reprisals have led to bloodshed throughout the country.[44] Since 2016, more than 450,000 people have fled their homes.[45] The conflict indirectly led to an upsurge in Boko Haram attacks, as the Cameroonian military largely withdrew from the north to focus on fighting the Ambazonian separatists.[46]

More than 30,000 people in northern Cameroon fled to Chad after ethnic clashes over access to water between Musgum fishermen and ethnic Arab Choa herders in December 2021.[47][48]

Politics and government

The President of Cameroon is elected and creates policy, administers government agencies, commands the armed forces, negotiates and ratifies treaties, and declares a state of emergency.[49] The president appoints government officials at all levels, from the prime minister (considered the official head of government), to the provincial governors and divisional officers.[50] The president is selected by popular vote every seven years.[1] There have been 2 presidents since the independence of Cameroon.

The National Assembly makes legislation. The body consists of 180 members who are elected for five-year terms and meet three times per year.[50] Laws are passed on a majority vote.[1] The 1996 constitution establishes a second house of parliament, the 100-seat Senate. The government recognises the authority of traditional chiefs, fons, and lamibe to govern at the local level and to resolve disputes as long as such rulings do not conflict with national law.[51][52]

Cameroon's legal system is a mixture of civil law, common law, and customary law.[1] Although nominally independent, the judiciary falls under the authority of the executive's Ministry of Justice.[51] The president appoints judges at all levels.[50] The judiciary is officially divided into tribunals, the court of appeal, and the supreme court. The National Assembly elects the members of a nine-member High Court of Justice that judges high-ranking members of government in the event they are charged with high treason or harming national security.[53][54]

Political culture

Cameroon is viewed as rife with corruption at all levels of government. In 1997, Cameroon established anti-corruption bureaus in 29 ministries, but only 25% became operational,[55] and in 2012, Transparency International placed Cameroon at number 144 on a list of 176 countries ranked from least to most corrupt.[56] On 18 January 2006, Biya initiated an anti-corruption drive under the direction of the National Anti-Corruption Observatory.[55] There are several high corruption risk areas in Cameroon, for instance, customs, public health sector and public procurement.[57] However, the corruption has gotten worse, regardless of the existing anti-corruption bureaus, as Transparency International ranked Cameroon 152 on a list of 180 countries in 2018.[58]

President Biya's Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (CPDM) was the only legal political party until December 1990. Numerous regional political groups have since formed. The primary opposition is the Social Democratic Front (SDF), based largely in the Anglophone region of the country and headed by John Fru Ndi.[59]

Biya and his party have maintained control of the presidency and the National Assembly in national elections, which rivals contend were unfair.[32] Human rights organisations allege that the government suppresses the freedoms of opposition groups by preventing demonstrations, disrupting meetings, and arresting opposition leaders and journalists.[60][61] In particular, English-speaking people are discriminated against; protests often escalate into violent clashes and killings.[62] In 2017, President Biya shut down the Internet in the English-speaking region for 94 days, at the cost of hampering five million people, including Silicon Mountain startups.[63]

Freedom House ranks Cameroon as "not free" in terms of political rights and civil liberties.[64] The last parliamentary elections were held on 9 February 2020.[65]

Foreign relations

Cameroon is a member of both the Commonwealth of Nations and La Francophonie.

Its foreign policy closely follows that of its main ally, France (one of its former colonial rulers).[66][67] Cameroon relies heavily on France for its defence,[51] although military spending is high in comparison to other sectors of government.[68]

President Biya has engaged in a decades-long clash with the government of Nigeria over possession of the oil-rich Bakassi peninsula.[59] Cameroon and Nigeria share a 1,000-mile (1,600 km) border and have disputed the sovereignty of the Bakassi peninsula. In 1994 Cameroon petitioned the International Court of Justice to resolve the dispute. The two countries attempted to establish a cease-fire in 1996; however, fighting continued for years. In 2002, the ICJ ruled that the Anglo-German Agreement of 1913 gave sovereignty to Cameroon. The ruling called for a withdrawal by both countries and denied the request by Cameroon for compensation due to Nigeria's long-term occupation.[69] By 2004, Nigeria had failed to meet the deadline to hand over the peninsula. A UN-mediated summit in June 2006 facilitated an agreement for Nigeria to withdraw from the region and both leaders signed the Greentree Agreement.[70] The withdrawal and handover of control was completed by August 2006.[71]

In July 2019, UN ambassadors of 37 countries, including Cameroon, signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region.[72]

Military

The Cameroon Armed Forces, (French: Forces armées camerounaises, FAC) consists of the country's army (Armée de Terre), the country's navy (Marine Nationale de la République (MNR), includes naval infantry), the Cameroonian Air Force (Armée de l'Air du Cameroun, AAC), and the Gendarmerie.[1]

Males and females that are 18 years of age up to 23 years of age and have graduated high school are eligible for military service. Those who join are obliged to complete 4 years of service. There is no conscription in Cameroon, but the government makes periodic calls for volunteers.[1]

Human rights

Human rights organisations accuse police and military forces of mistreating and even torturing criminal suspects, ethnic minorities, homosexuals, and political activists.[60][61][73][74] United Nations figures indicate that more than 21,000 people have fled to neighboring countries, while 160,000 have been internally displaced by the violence, many reportedly hiding in forests.[75] Prisons are overcrowded with little access to adequate food and medical facilities,[73][74] and prisons run by traditional rulers in the north are charged with holding political opponents at the behest of the government.[61] However, since the first decade of the 21st century, an increasing number of police and gendarmes have been prosecuted for improper conduct.[73] On 25 July 2018, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein expressed deep concern about reports of violations and abuses in the English-speaking Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon.[75]

Same-sex sexual acts are banned by section 347-1 of the penal code with a penalty of from 6 months up to 5 years' imprisonment.[76]

Since December 2020, Human Rights Watch claimed that Islamist armed group Boko Haram has stepped up attacks and killed at least 80 civilians in towns and villages in the Far North region of Cameroon.[77]

Administrative divisions

The constitution divides Cameroon into 10 semi-autonomous regions, each under the administration of an elected Regional Council. Each region is headed by a presidentially appointed governor.[49]

These leaders are charged with implementing the will of the president, reporting on the general mood and conditions of the regions, administering the civil service, keeping the peace, and overseeing the heads of the smaller administrative units. Governors have broad powers: they may order propaganda in their area and call in the army, gendarmes, and police.[49] All local government officials are employees of the central government's Ministry of Territorial Administration, from which local governments also get most of their budgets.[14]

The regions are subdivided into 58 divisions (French départements). These are headed by presidentially appointed divisional officers (préfets). The divisions are further split into sub-divisions (arrondissements), headed by assistant divisional officers (sous-prefets). The districts, administered by district heads (chefs de district), are the smallest administrative units.[78]

The three northernmost regions are the Far North (Extrême Nord), North (Nord), and Adamawa (Adamaoua). Directly south of them are the Centre (Centre) and East (Est). The South Province (Sud) lies on the Gulf of Guinea and the southern border. Cameroon's western region is split into four smaller regions: the Littoral (Littoral) and South-West (Sud-Ouest) regions are on the coast, and the North-West (Nord-Ouest) and West (Ouest) regions are in the western grassfields.[78]

Geography

At 475,442 square kilometres (183,569 sq mi), Cameroon is the world's 53rd-largest country.[79] The country is located in Central and West Africa, known as the hinge of Africa, on the Bight of Bonny, part of the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean.[80] Cameroon lies between latitudes 1° and 13°N, and longitudes 8° and 17°E. Cameroon controls 12 nautical miles of the Atlantic Ocean.

Tourist literature describes Cameroon as "Africa in miniature" because it exhibits all major climates and vegetation of the continent: coast, desert, mountains, rainforest, and savanna.[81] The country's neighbours are Nigeria and the Atlantic Ocean to the west; Chad to the northeast; the Central African Republic to the east; and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo to the south.[1]

Cameroon is divided into five major geographic zones distinguished by dominant physical, climatic, and vegetative features. The coastal plain extends 15 to 150 kilometres (9 to 93 mi) inland from the Gulf of Guinea[82] and has an average elevation of 90 metres (295 ft).[83] Exceedingly hot and humid with a short dry season, this belt is densely forested and includes some of the wettest places on earth, part of the Cross-Sanaga-Bioko coastal forests.[84][85]

The South Cameroon Plateau rises from the coastal plain to an average elevation of 650 metres (2,133 ft).[86] Equatorial rainforest dominates this region, although its alternation between wet and dry seasons makes it less humid than the coast. This area is part of the Atlantic Equatorial coastal forests ecoregion.[87]

An irregular chain of mountains, hills, and plateaus known as the Cameroon range extends from Mount Cameroon on the coast—Cameroon's highest point at 4,095 metres (13,435 ft)[88]—almost to Lake Chad at Cameroon's northern border at 13°05'N. This region has a mild climate, particularly on the Western High Plateau, although rainfall is high. Its soils are among Cameroon's most fertile, especially around volcanic Mount Cameroon.[88] Volcanism here has created crater lakes. On 21 August 1986, one of these, Lake Nyos, belched carbon dioxide and killed between 1,700 and 2,000 people.[89] This area has been delineated by the World Wildlife Fund as the Cameroonian Highlands forests ecoregion.[90]

The southern plateau rises northward to the grassy, rugged Adamawa Plateau. This feature stretches from the western mountain area and forms a barrier between the country's north and south. Its average elevation is 1,100 metres (3,609 ft),[86] and its average temperature ranges from 22 °C (71.6 °F) to 25 °C (77 °F) with high rainfall between April and October peaking in July and August.[91][92] The northern lowland region extends from the edge of the Adamawa to Lake Chad with an average elevation of 300 to 350 metres (984 to 1,148 ft).[88] Its characteristic vegetation is savanna scrub and grass. This is an arid region with sparse rainfall and high median temperatures.[93]

Cameroon has four patterns of drainage. In the south, the principal rivers are the Ntem, Nyong, Sanaga, and Wouri. These flow southwestward or westward directly into the Gulf of Guinea. The Dja and Kadéï drain southeastward into the Congo River. In northern Cameroon, the Bénoué River runs north and west and empties into the Niger. The Logone flows northward into Lake Chad, which Cameroon shares with three neighbouring countries.[94]

Economy and infrastructure

Cameroon's per capita GDP (Purchasing power parity) was estimated as US$3,700 in 2017. Major export markets include the Netherlands, France, China, Belgium, Italy, Algeria, and Malaysia.[1]

Cameroon has had a decade of strong economic performance, with GDP growing at an average of 4% per year. During the 2004–2008 period, public debt was reduced from over 60% of GDP to 10% and official reserves quadrupled to over US$3 billion.[95] Cameroon is part of the Bank of Central African States (of which it is the dominant economy),[96] the Customs and Economic Union of Central Africa (UDEAC) and the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[97] Its currency is the CFA franc.[1]

Unemployment was estimated at 3.38% in 2019,[98] and 23.8% of the population was living below the international poverty threshold of US$1.90 a day in 2014.[99] Since the late 1980s, Cameroon has been following programmes advocated by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) to reduce poverty, privatise industries, and increase economic growth.[51] The government has taken measures to encourage tourism in the country.[100]

An estimated 70% of the population farms, and agriculture comprised an estimated 16.7% of GDP in 2017.[1] Most agriculture is done at the subsistence scale by local farmers using simple tools. They sell their surplus produce, and some maintain separate fields for commercial use. Urban centres are particularly reliant on peasant agriculture for their foodstuffs. Soils and climate on the coast encourage extensive commercial cultivation of bananas, cocoa, oil palms, rubber, and tea. Inland on the South Cameroon Plateau, cash crops include coffee, sugar, and tobacco. Coffee is a major cash crop in the western highlands, and in the north, natural conditions favour crops such as cotton, groundnuts, and rice. Production of Fairtrade cotton was initiated in Cameroon in 2004.[101]

Livestock are raised throughout the country.[102] Fishing employs 5,000 people and provides over 100,000 tons of seafood each year.[103][104] Bushmeat, long a staple food for rural Cameroonians, is today a delicacy in the country's urban centres. The commercial bushmeat trade has now surpassed deforestation as the main threat to wildlife in Cameroon.[105][106]

The southern rainforest has vast timber reserves, estimated to cover 37% of Cameroon's total land area.[104] However, large areas of the forest are difficult to reach. Logging, largely handled by foreign-owned firms,[104] provides the government US$60 million a year in taxes (as of 1998), and laws mandate the safe and sustainable exploitation of timber. Nevertheless, in practice, the industry is one of the least regulated in Cameroon.[107]

Factory-based industry accounted for an estimated 26.5% of GDP in 2017.[1] More than 75% of Cameroon's industrial strength is located in Douala and Bonabéri. Cameroon possesses substantial mineral resources, but these are not extensively mined (see Mining in Cameroon).[51] Petroleum exploitation has fallen since 1986, but this is still a substantial sector such that dips in prices have a strong effect on the economy.[108] Rapids and waterfalls obstruct the southern rivers, but these sites offer opportunities for hydroelectric development and supply most of Cameroon's energy. The Sanaga River powers the largest hydroelectric station, located at Edéa. The rest of Cameroon's energy comes from oil-powered thermal engines. Much of the country remains without reliable power supplies.[109]

Transport in Cameroon is often difficult. Only 6.6% of the roadways are tarred.[1] Roadblocks often serve little other purpose than to allow police and gendarmes to collect bribes from travellers.[110] Road banditry has long hampered transport along the eastern and western borders, and since 2005, the problem has intensified in the east as the Central African Republic has further destabilised.[111]

Intercity bus services run by multiple private companies connect all major cities. They are the most popular means of transportation followed by the rail service Camrail. Rail service runs from Kumba in the west to Bélabo in the east and north to Ngaoundéré.[112] International airports are located in Douala and Yaoundé, with a third under construction in Maroua.[113] Douala is the country's principal seaport.[114] In the north, the Bénoué River is seasonally navigable from Garoua across into Nigeria.[115]

Although press freedoms have improved since the first decade of the 21st century, the press is corrupt and beholden to special interests and political groups.[116] Newspapers routinely self-censor to avoid government reprisals.[73] The major radio and television stations are state-run and other communications, such as land-based telephones and telegraphs, are largely under government control.[117] However, cell phone networks and Internet providers have increased dramatically since the first decade of the 21st century[118] and are largely unregulated.[61]

Demographics

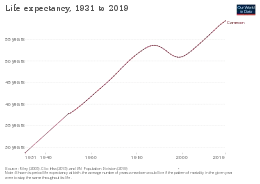

The population of Cameroon was 27,198,628 in 2021.[119][120] The life expectancy was 62.3 years (60.6 years for males and 64 years for females).[1]

Cameroon has slightly more women (50.5%) than men (49.5%). Over 60% of the population is under age 25. People over 65 years of age account for only 3.11% of the total population.[1]

Cameroon's population is almost evenly divided between urban and rural dwellers.[121] Population density is highest in the large urban centres, the western highlands, and the northeastern plain.[122] Douala, Yaoundé, and Garoua are the largest cities. In contrast, the Adamawa Plateau, southeastern Bénoué depression, and most of the South Cameroon Plateau are sparsely populated.[123]

According to the World Health Organization, the fertility rate was 4.8 in 2013 with a population growth rate of 2.56%.[124]

People from the overpopulated western highlands and the underdeveloped north are moving to the coastal plantation zone and urban centres for employment.[125] Smaller movements are occurring as workers seek employment in lumber mills and plantations in the south and east.[126] Although the national sex ratio is relatively even, these out-migrants are primarily males, which leads to unbalanced ratios in some regions.[127]

Both monogamous and polygamous marriage are practised, and the average Cameroonian family is large and extended.[128] In the north, women tend to the home, and men herd cattle or work as farmers. In the south, women grow the family's food, and men provide meat and grow cash crops. Cameroonian society is male-dominated, and violence and discrimination against women is common.[61][73][129]

The number of distinct ethnic and linguistic groups in Cameroon is estimated to be between 230 and 282.[130][131] The Adamawa Plateau broadly bisects these into northern and southern divisions. The northern peoples are Sudanic groups, who live in the central highlands and the northern lowlands, and the Fulani, who are spread throughout northern Cameroon. A small number of Shuwa Arabs live near Lake Chad. Southern Cameroon is inhabited by speakers of Bantu and Semi-Bantu languages. Bantu-speaking groups inhabit the coastal and equatorial zones, while speakers of Semi-Bantu languages live in the Western grassfields. Some 5,000 Gyele and Baka Pygmy peoples roam the southeastern and coastal rainforests or live in small, roadside settlements.[132] Nigerians make up the largest group of foreign nationals.[133]

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Douala  Yaoundé |

1 | Douala | Littoral | 1,906,962 |  Bafoussam  Bamenda | ||||

| 2 | Yaoundé | Centre | 1,817,524 | ||||||

| 3 | Bafoussam | West | 800,000 | ||||||

| 4 | Bamenda | Northwest | 269,530 | ||||||

| 5 | Garoua | North | 235,996 | ||||||

| 6 | Maroua | Far North | 201,371 | ||||||

| 7 | Ngaoundéré | Adamawa | 152,698 | ||||||

| 8 | Kumba | Southwest | 144,268 | ||||||

| 9 | Nkongsamba | Littoral | 104,050 | ||||||

| 10 | Buea | Southwest | 90,090 | ||||||

Refugees

In 2007, Cameroon hosted approximately 97,400 refugees and asylum seekers. Of these, 49,300 were from the Central African Republic (many driven west by war),[135] 41,600 from Chad, and 2,900 from Nigeria.[136] Kidnappings of Cameroonian citizens by Central African bandits have increased since 2005.[111]

In the first months of 2014, thousands of refugees fleeing the violence in the Central African Republic arrived in Cameroon.[137]

On 4 June 2014, AlertNet reported:

Almost 90,000 people have fled to neighbouring Cameroon since December and up to 2,000 a week, mostly women and children, are still crossing the border, the United Nations said.

"Women and children are arriving in Cameroon in a shocking state, after weeks, sometimes months, on the road, foraging for food," said Ertharin Cousin, executive director of the World Food Programme (WFP).[138]

Languages

Both English and French are official languages, although French is by far the most understood language (more than 80%).[139] German, the language of the original colonisers, has long since been displaced by French and English. Cameroonian Pidgin English is the lingua franca in the formerly British-administered territories.[140] A mixture of English, French, and Pidgin called Camfranglais has been gaining popularity in urban centres since the mid-1970s.[141][142] The government encourages bilingualism in English and French, and as such, official government documents, new legislation, ballots, among others, are written and provided in both languages. As part of the initiative to encourage bilingualism in Cameroon, six of the eight universities in the country are entirely bilingual.

In addition to the colonial languages, there are approximately 250 other languages spoken by nearly 20 million Cameroonians.[8] It is because of this that Cameroon is considered one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world.[7]

Many Memorandums of Understanding have been signed with Germany for the study of German, which still enjoys huge popularity among pupils and students, with 300,000 people learning or speaking German in Cameroon in 2010. Today, Cameroon is one of the African countries with the highest number of people with knowledge of German.

In the northern regions of the Far North, the North, and Adamawa, the Fulani language Fulfulde is the lingua franca with French merely serving as an administrative language. However, Chadian Arabic in the Far North region's department of Logone-et-Chari acts as the lingua franca irrespective of ethnic groups.

In 2017 there were language protests by the anglophone population against perceived oppression by francophone speakers.[143] The military was deployed against the protesters and people were killed, hundreds imprisoned and thousands fled the country.[144] This culminated in the declaration of an independent Republic of Ambazonia,[145] which has since evolved into the Anglophone Crisis.[143] It is estimated that by June 2020, 740,000 people had been internally displaced as a result of this crisis.[146]

Religion

Cameroon has a high level of religious freedom and diversity.[73] The predominant faith is Christianity, practised by about two-thirds of the population, while Islam is a significant minority faith, adhered to by about one-fourth. In addition, traditional faiths are practised by many. Muslims are most concentrated in the north, while Christians are concentrated primarily in the southern and western regions, but practitioners of both faiths can be found throughout the country.[147] Large cities have significant populations of both groups.[147] Muslims in Cameroon are divided into Sufis, Salafis,[148] Shias, and non-denominational Muslims.[148][149]

People from the North-West and South-West provinces, which used to be a part of British Cameroons, have the highest proportion of Protestants. The French-speaking regions of the southern and western regions are largely Catholic.[147] Southern ethnic groups predominantly follow Christian or traditional African animist beliefs, or a syncretic combination of the two. People widely believe in witchcraft, and the government outlaws such practices.[150] Suspected witches are often subject to mob violence.[73] The Islamist jihadist group Ansar al-Islam has been reported as operating in North Cameroon.[151]

In the northern regions, the locally dominant Fulani ethnic group is mostly Muslim, but the overall population is fairly evenly divided among Muslims, Christians, and followers of indigenous religious beliefs (called Kirdi ("pagan") by the Fulani).[147] The Bamum ethnic group of the West Region is largely Muslim.[147] Native traditional religions are practised in rural areas throughout the country but rarely are practised publicly in cities, in part because many indigenous religious groups are intrinsically local in character.[147]

Education and health

In 2013, the total adult literacy rate of Cameroon was estimated to be 71.3%. Among youths age 15–24 the literacy rate was 85.4% for males and 76.4% for females.[152] Most children have access to state-run schools that are cheaper than private and religious facilities.[153] The educational system is a mixture of British and French precedents[154] with most instruction in English or French.[155]

Cameroon has one of the highest school attendance rates in Africa.[153] Girls attend school less regularly than boys do because of cultural attitudes, domestic duties, early marriage, pregnancy, and sexual harassment. Although attendance rates are higher in the south,[153] a disproportionate number of teachers are stationed there, leaving northern schools chronically understaffed.[73] In 2013, the primary school enrollment rate was 93.5%.[152]

School attendance in Cameroon is also affected by child labour. Indeed, the United States Department of Labor Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor reported that 56% of children aged 5 to 14 were working children and that almost 53% of children aged 7 to 14 combined work and school.[156] In December 2014, a List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor issued by the Bureau of International Labor Affairs mentioned Cameroon among the countries that resorted to child labor in the production of cocoa.[157]

The quality of health care is generally low.[158] Life expectancy at birth is estimated to be 56 years in 2012, with 48 healthy life years expected.[124] Fertility rate remains high in Cameroon with an average of 4.8 births per woman and an average mother's age of 19.7 years old at first birth.[124] In Cameroon, there is only one doctor for every 5,000 people, according to the World Health Organization.[159] In 2014, just 4.1% of total GDP expenditure was allocated to healthcare.[160] Due to financial cuts in the health care system, there are few professionals. Doctors and nurses who were trained in Cameroon, emigrate because in Cameroon the payment is poor while the workload is high. Nurses are unemployed even though their help is needed. Some of them help out voluntarily so they will not lose their skills.[161] Outside the major cities, facilities are often dirty and poorly equipped.[162]

In 2012, the top three deadly diseases were HIV/AIDS, lower respiratory tract infection, and diarrheal diseases.[124] Endemic diseases include dengue fever, filariasis, leishmaniasis, malaria, meningitis, schistosomiasis, and sleeping sickness.[163] The HIV/AIDS prevalence rate in 2016 was estimated at 3.8% for those aged 15–49,[164] although a strong stigma against the illness keeps the number of reported cases artificially low.[158] 46,000 children under age 14 were estimated to be living with HIV in 2016. In Cameroon, 58% of those living with HIV know their status, and just 37% receive ARV treatment. In 2016, 29,000 deaths due to AIDS occurred in both adults and children.[164]

Breast ironing, a traditional practice that is prevalent in Cameroon, may affect girls' health.[165][166][167][168] Female genital mutilation (FGM), while not widespread, is practiced among some populations; according to a 2013 UNICEF report,[169] 1% of women in Cameroon have undergone FGM. Also impacting women and girls' health, the contraceptive prevalence rate is estimated to be just 34.4% in 2014. Traditional healers remain a popular alternative to evidence-based medicine.[170]

Culture

Music and dance

Music and dance are integral parts of Cameroonian ceremonies, festivals, social gatherings, and storytelling.[171][172] Traditional dances are highly choreographed and separate men and women or forbid participation by one sex altogether.[173] The dances' purposes range from pure entertainment to religious devotion.[172] Traditionally, music is transmitted orally. In a typical performance, a chorus of singers echoes a soloist.[174]

Musical accompaniment may be as simple as clapping hands and stamping feet,[175] but traditional instruments include bells worn by dancers, clappers, drums and talking drums, flutes, horns, rattles, scrapers, stringed instruments, whistles, and xylophones; combinations of these vary by ethnic group and region. Some performers sing complete songs alone, accompanied by a harplike instrument.[174][176]

Popular music styles include ambasse bey of the coast, assiko of the Bassa, mangambeu of the Bangangte, and tsamassi of the Bamileke.[177] Nigerian music has influenced Anglophone Cameroonian performers, and Prince Nico Mbarga's highlife hit "Sweet Mother" is the top-selling African record in history.[178]

The two most popular music styles are makossa and bikutsi. Makossa developed in Douala and mixes folk music, highlife, soul, and Congo music. Performers such as Manu Dibango, Francis Bebey, Moni Bilé, and Petit-Pays popularised the style worldwide in the 1970s and 1980s. Bikutsi originated as war music among the Ewondo. Artists such as Anne-Marie Nzié developed it into a popular dance music beginning in the 1940s, and performers such as Mama Ohandja and Les Têtes Brulées popularised it internationally during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.[179][180]

Holidays

The most notable holiday associated with patriotism in Cameroon is National Day, also called Unity Day. Among the most notable religious holidays are Assumption Day, and Ascension Day, which is typically 39 days after Easter. In the Northwest and Southwest provinces, collectively called Ambazonia, October 1 is considered a national holiday, a date Ambazonians consider the day of their independence from Cameroon.[181]

Cuisine

Cuisine varies by region, but a large, one-course, evening meal is common throughout the country. A typical dish is based on cocoyams, maize, cassava (manioc), millet, plantains, potatoes, rice, or yams, often pounded into dough-like fufu. This is served with a sauce, soup, or stew made from greens, groundnuts, palm oil, or other ingredients.[182] Meat and fish are popular but expensive additions, with chicken often reserved for special occasions.[183] Dishes are often quite spicy; seasonings include salt, red pepper sauce, and maggi.[184][185][186]

Cutlery is common, but food is traditionally manipulated with the right hand. Breakfast consists of leftovers of bread and fruit with coffee or tea. Generally breakfast is made from wheat flour in various different foods such as puff-puff (doughnuts), accra banana made from bananas and flour, bean cakes, and many more. Snacks are popular, especially in larger towns where they may be bought from street vendors.[187][188]

Water, palm wine, and millet beer are the traditional mealtime drinks, although beer, soda, and wine have gained popularity. 33 Export beer is the official drink of the national football team and one of the most popular brands, joining Castel, Amstel Brewery, and Guinness.

Fashion

Cameroon's relatively large and diverse population is likewise diverse in its fashions. Climate, religious, ethnic and cultural beliefs, and the influences of colonialism, imperialism, and globalization are all factors in contemporary Cameroonian dress.

Notable articles of clothing include: Pagnes, sarongs worn by Cameroon women; Chechia, a traditional hat; kwa, a male handbag; and Gandura, male custom attire.[189] Wrappers and loincloths are used extensively by both women and men but their use varies by region, with influences from Fulani styles more present in the north and Igbo and Yoruba styles more often in the south and west.[190]

Imane Ayissi is one of Cameroon's top fashion designers and has received international recognition.[191]

Local arts and crafts

Traditional arts and crafts are practiced throughout the country for commercial, decorative, and religious purposes. Woodcarvings and sculptures are especially common.[192] The high-quality clay of the western highlands is used for pottery and ceramics.[172] Other crafts include basket weaving, beadworking, brass and bronze working, calabash carving and painting, embroidery, and leather working. Traditional housing styles use local materials and vary from temporary wood-and-leaf shelters of nomadic Mbororo to the rectangular mud-and-thatch homes of southern peoples. Dwellings of materials such as cement and tin are increasingly common.[193] Contemporary art is mainly promoted by independent cultural organizations (Doual'art, Africréa) and artist-run initiatives (Art Wash, Atelier Viking, ArtBakery).[194]

Literature

Cameroonian literature has concentrated on both European and African themes. Colonial-era writers such as Louis-Marie Pouka and Sankie Maimo were educated by European missionary societies and advocated assimilation into European culture to bring Cameroon into the modern world.[195] After World War II, writers such as Mongo Beti and Ferdinand Oyono analysed and criticised colonialism and rejected assimilation.[196][197][198]

Films and literature

Shortly after independence, filmmakers such as Jean-Paul Ngassa and Thérèse Sita-Bella explored similar themes.[199][200] In the 1960s, Mongo Beti, Ferdinand Léopold Oyono and other writers explored postcolonialism, problems of African development, and the recovery of African identity.[201] In the mid-1970s, filmmakers such as Jean-Pierre Dikongué Pipa and Daniel Kamwa dealt with the conflicts between traditional and postcolonial society. Literature and films during the next two decades focused more on wholly Cameroonian themes.[202]

Sports

National policy strongly advocates sport in all forms. Traditional sports include canoe racing and wrestling, and several hundred runners participate in the 40 km (25 mi) Mount Cameroon Race of Hope each year.[203] Cameroon is one of the few tropical countries to have competed in the Winter Olympics.

Sport in Cameroon is dominated by football. Amateur football clubs abound, organised along ethnic lines or under corporate sponsors. The national team has been one of the most successful in Africa since its strong showing in the 1982 and 1990 FIFA World Cups. Cameroon has won five African Cup of Nations titles and the gold medal at the 2000 Olympics.[204]

Cameroon was the host country of the Women Africa Cup of Nations in November–December 2016,[205] the 2020 African Nations Championship and the 2021 Africa Cup of Nations. The women's football team is known as the "Indomitable Lionesses", and like their men's counterparts, are also successful at international stage, although it has not won any major trophy.

Cricket has also entered into Cameroon as an emerging sport with the Cameroon Cricket Federation participating in international matches [206]

Cameroon has produced multiple National Basketball Association players including Pascal Siakam, Joel Embiid, D. J. Strawberry, Ruben Boumtje-Boumtje, and Luc Mbah a Moute.[207]

The current UFC Heavyweight Champion Francis Ngannou hails from Cameroon.[208]

See also

- Index of Cameroon-related articles

- Outline of Cameroon

- Telephone numbers in Cameroon

Notes

- "Cameroon § People and Society". The World Factbook (2022 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 16 May 2022.

- "National Profiles".

- "Democracy Index 2020". Economist Intelligence Unit. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2021". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". databank.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Pereltsvaig, Asya (16 June 2011). "Linguistic diversity in Africa and Europe – Languages Of The World". languagesoftheworld.info. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Kouega, Jean-Paul. 'The Language Situation in Cameroon', Current Issues in Language Planning, vol. 8/no. 1, (2007), pp. 3–94.

- "Cameroon". Ethnologue. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- Highest Average Annual Precipitation Extremes. Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation, National Climatic Data Center. 25 May 2012. Last accessed 1 July 2019.

- Cameroon (adj.) nation in West Africa, its name is taken from the Anglicized form of the former name of the River Wouri, which was called by the Portuguese Rio dos Camarões "river of prawns" (16c.) for the abundance of these they found in its broad estuary. camarões is from Latin cammarus "a crawfish, prawn."

- "Camarões: o que os crustáceos têm a ver com o país? ("Cameroon: what do the crustaceans have to do with the country?")". Veja. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 2.

- "Cameroon". US Department of State. 25 August 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- Njung, GN, Lucas Tazanu Mangula, and Emmanuel Nfor Nkwiyir (2003). Introduction to History: Cameroon. ANUCAM, pp. 5–6.

- Pondi, J. E. (1997). "Cameroon and the Commonwealth of nations". The Round Table. 86 (344): 563–570. doi:10.1080/00358539708454389.

- Fanso, V. G. (1989). Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd., p. 84, ISBN 0333471210.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 59

- "Bamum". National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "historyworld". Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 125.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 5.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 4.

- Terretta, M. (2010). "Cameroonian Nationalists Go Global: From Forest Maquis to a Pan-African Accra". The Journal of African History. 51 (2): 189–212. doi:10.1017/S0021853710000253. S2CID 154604590.

- Takougang, J. (2003). "Nationalism, democratisation and political opportunism in Cameroon". Journal of Contemporary African Studies. 21 (3): 427–445. doi:10.1080/0258900032000142455. S2CID 153564848.

- Diane Cook (2 September 2014). Cameroon. Mason Crest. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-4222-9434-5.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 6.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 19.

- "20 May National Day". Presidency of the Republic of Cameroon. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 7.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 8.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 9.

- Ginna Violet Yella. "Freedom of Trade Union Membership: An Appraisal of the 1992 Labour Code of Cameroon" United International Journal for Research & Technology (UIJRT) 1.2 (2019): 18–25.

- Cameroon: Presidents Obasanjo And Biya Shake Hands on Disputed Bakassi Peninsula Archived 17 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Allafrica, 13 June 2006

- Cameroon Rebels Threaten Security in Oil-Rich Gulf of Guinea, Jamestown Foundation, 24 November 2010. Accessed 28 Aug. 2018.

- Ngwane, George. "Preventing renewed violence through peace building in the Bakassi peninsula (Cameroon)."

- Nkemngu, Martin A. (11 March 2008). "Facts and Figures of the Tragic Protests", Cameroon Tribune. Retrieved 12 March 2008.(subscription required) Archived 13 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Matthews, Andy (12 March 2008). "Cameroon protests in USA Archived 6 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine", Africa News. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- "Cameroon, Chad Deploy Troops to Fight Boko Haram – Nigeria". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- Boko Haram has been repelled, Cameroon's leader declares, CBC News, 30 September 2018. Accessed 18 June 2019.

- Radina Gigova (15 December 2016). "Rights groups call for probe into protesters' deaths in Cameroon". CNN. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "Cameroon internet shut for separatists". BBC News. 2 October 2017. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Burning Cameroon: Images you're not meant to see". BBC News. 25 June 2018. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Ekonde, By: Daniel; News (18 November 2020). "The world's most neglected conflict". New Frame. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - Tisdall, Simon (9 June 2019). "In a world full of wars, why are so many of them ignored?". The Guardian.

- Insecurity Escalates In North Region As Gov't, Military Concentrate In Anglophone Regions Archived 12 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The National Times, 25 February 2019.Accessed 25 February 2019.

- "Thousands flee northern Cameroon after deadly intercommunal clashes". France 24. 10 December 2021.

- "Northern Cameroon bears brunt of inter-ethnic clashes, 22 dead, 30 injured". Africanews. 14 December 2021.

- Neba 250.

- "Cameroon: Government". Michigan State University: Broad College of Business. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "U.S. Relations With Cameroon ". United States Department of State. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- Neba 252.

- Abdourhamane, Boubacar Issa. "Cameroon: Institutional Situation". Montesquieu University of Bordeaux. Archived from the original on 21 September 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Government in Cameroon". Commonwealth of Nations. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Cameroon: New anti-corruption drive leaves many sceptical Archived 21 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine". 27 January 2006. IRIN. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- "Corruption Perceptions Index 2012 Archived 29 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine". Transparency International.

- "Business Corruption in Cameroon". Business Anti-Corruption Portal. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "2018 – CPI". Transparency.org. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- West 11.

- "Cameroon". Amnesty International Report 2006. Amnesty International. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- "Cameroon (2006)". Country Report: 2006 Edition. Freedom House. 13 January 2012. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- Radina Gigova (15 December 2016). "Rights groups call for probe into protesters' deaths in Cameroon". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Kieron Monks (3 February 2017). "Cameroon goes offline after Anglophone revolt". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Cameroon is rated at six in both categories on a scale of one to seven, with one being "most free" and seven being "least free". Freedom House.

- Kandemeh, Emmanuel (17 July 2007). "Journalists Warned against Declaring Election Results", Cameroon Tribune. Retrieved 18 July 2007 (subscription required).

- DeLancey and DeLancey 126

- Ngoh 328.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 30.

- Banerjee, Marc Lacey With Neela (11 October 2002). "Court Rules for Cameroon In Oil Dispute With Nigeria". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Agreement Transferring Authority over Bakassi Peninsula from Nigeria to Cameroon 'Triumph for the Rule of Law' Secretary-General Says in Message for Ceremony". www.un.org. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Cameroon profile". BBC News. 1 November 2017. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Which Countries Are For or Against China's Xinjiang Policies?". The Diplomat. 15 July 2019.

- "Cameroon ". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 6 March 2007. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- "2006 Elections to the Human Rights Council: Background information on candidate countries". Amnesty International. 30 April 2006. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- "OHCHR – UN Human Rights Chief deeply alarmed by reports of serious rights breaches in Cameroon". Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Ottosson, Daniel (May 2008). "State-sponsored Homophobia: A world survey of laws prohibiting same sex activity between consenting adults" (PDF). International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA). p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2009.

- "Cameroon: Boko Haram Attacks Escalate in Far North". Human Rights Watch. 5 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- "Core document forming part of the reports of States Parties: Cameroon". UNHCHR. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Demographic Yearbook 2004 Archived 14 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations Statistics Division.

- "Country Profiles". UCLA African Studies Center. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 16.

- Fomensky, R., M. Gwanfogbe, and F. Tsala, editorial advisers (1985) Macmillan School Atlas for Cameroon. Malaysia: Macmillan Education, p. 6

- Neba 14.

- Neba 28.

- "Highest Average Annual Precipitation Extremes Archived 25 May 2012 at archive.today". Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation, National Climatic Data Center, 9 August 2004. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- Neba 16.

- "ICAM of Kribi Campo" (PDF). UNIDO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Neba 17.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 161 report 1,700 killed; Hudgens and Trillo 1054 say "at least 2,000"; West 10 says "more than 2,000".

- "Cameroon Highlands Forests". WWF. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Gwanfogbe, Mathew; Meligui, Ambrose; Moukam, Jean and Nguoghia, Jeanette (1983). Geography of Cameroon. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education, p. 20, ISBN 0333366905.

- Neba 29.

- Green, RH (1969). "The Economy of Cameroon Federal Republic". In Robson, Peter, and DA Lury (eds). The Economies of Africa, p. 239. Allen and Unwin.

- "Country Files: Cameroon". UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- "Cameroon Financial Sector Profile". MFW4A. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- Musa, Tansa (8 April 2008). "Biya plan to keep power in Cameroon clears hurdle Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- "The business law portal in Africa". OHADA. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- "Cameroon Unemployment rate – data, chart". TheGlobalEconomy.com. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) – Cameroon | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Cameroon Business Mission Fact Sheet 2010–2011" (PDF). Netherlands-African Business Council. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- Fairtrade International, University of Greenwich and Institute of Development Studies, Fairtrade Cotton: Assessing Impact in Mali, Senegal, Cameroon and India, published May 2011, accessed 31 August 2021

- "Cameroon livestock production map". FAO. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Som, Julienne. "Women's role in Cameroon fishing communities". FAO. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Cameroon". AWF. 28 February 2013. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "UK project tackles bushmeat diet". BBC. 10 April 2002. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Cameroon's bushmeat dilemma". BBC. 14 March 2008. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Logging in the Green Heart of Africa". WWF. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Cossé, Stéphane (2006). "Strengthening Transparency in the Oil Sector in Cameroon" (PDF). IMF. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Prevost, Yves. "Harnessing Central Africa's Hydropower Potential" (PDF). Climate Parliament. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Hudgens and Trillo 1036.

- Musa, Tansa (27 June 2007). "Gunmen kill one, kidnap 22 in Cameroon near CAR Archived 29 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "Getting around Cameroon". World Travel Guide. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Equipment for the Future Maroua International Airport". Cameroon Online. 3 April 2013. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "SOS Children's Village Douala". SOS Children's Villages. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 68.

- "Cameroon – Annual Report 2007".

- Mbaku 20.

- Mbaku 20–1.

- "World Population Prospects 2022". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX). population.un.org ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- West 3.

- Neba 109–11.

- Neba 111.

- "Cameroon: WHO Statistical Profile" (PDF). World Health Organization. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2017.

- Neba 105–6.

- Neba 106.

- Neba 103–4.

- Mbaku 139.

- Mbaku 141.

- Neba 65, 67.

- West 13.

- Neba 48.

- Neba 108.

- "Cameroon: Regions, Major Cities & Towns". Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information (in Luxembourgish). 9 April 1976. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (28 May 2007). "Cameroon: Population Movement; DREF Bulletin no. MDRCM004". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- "World Refugee Survey 2008". U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. 19 June 2008. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008.

- "Cameroon: Location of Refugees and Main Entry Points (as of 02 May 2014) – Cameroon". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- Nguyen, Katie (4 June 2014). "Cameroon: Starving, Exhausted CAR Refugees Stream Into Cameroon – UN". allAfrica.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- Nathan, Fernand (ed.) (2010) La langue francaise dans le monde en 2010 Archived 3 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 2098824076.

- Neba 94.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 131

- Niba, Francis Ngwa (20 February 2007). "New language for divided Cameroon Archived 21 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- Genin, Aaron (11 February 2019). "AFRICAN POWDER KEG: CAMEROONIAN CONFLICT AND AFRICAN SECURITY". The California Review. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Deaths and detentions as Cameroon cracks down on anglophone activists Archived 3 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, 2018

- Ani, Kelechi Johnmary, Gabriel Tiobo Wose Kinge, and Victor Ojakorotu. "Political crisis, protests and implications on nation building in Cameroon." African Renaissance 15.Special Issue 1 (2018): 121–139.

- "Relief Web Humanitarian Dashboard". Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- "July–December, 2010 International Religious Freedom Report – Cameroon". US Department of State. 8 April 2011. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- "The veil in west Africa: Banning the burqa: Why more countries are outlawing the full-face veil". The Economist. 13 February 2016. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Pew Forum on Religious & Public life. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2013

- Geschiere, Peter (1997). The Modernity of Witchcraft: Politics and the Occult in Postcolonial Africa. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, pp. 169–170, ISBN 0813917034.

- Boko Haram timeline: From preachers to slave raiders Archived 14 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. 15 May 2013. retrieved 19 June 2013

- "Statistics". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Mbaku 15.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 105–6.

- Mbaku 16.

- 2013 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor -Cameroon Archived 3 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Dol.gov. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor Archived 10 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Dol.gov. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 21.

- CNN Staff. "3 medical marvels saving lives". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- "UNdata | country profile | Cameroon". data.un.org. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Rose Futrih N. Njini (December 2012). "The need is so great". D+C Development and Cooperation/ dandc.eu. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- West 64.

- West 58–60.

- "Cameroon". www.unaids.org. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Joe, Randy. (23 June 2006) Africa | Cameroon girls battle 'breast ironing' Archived 11 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- BBC World Service – Outlook, Fighting 'Breast Ironing' in Cameroon Archived 20 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Bbc.co.uk (16 January 2014). Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Campaigners warn of 'breast ironing' in the UK – Channel 4 News Archived 20 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Channel4.com (18 April 2014). Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Bawe, Rosaline Ngunshi (24 August 2011) Breast Ironing : A harmful traditional practice in Cameroon Archived 26 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Gender Empowerment and Development(GeED)

- UNICEF 2013 Archived 5 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 27.

- Lantum, Daniel M., and Martin Ekeke Monono (2005). "Republic of Cameroon", Who Global Atlas of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine. World Health Organization, p. 14.

- Mbaku 189

- West 18.

- Mbaku 204.

- Mbaku 189.

- Mbaku 191.

- West 18–9.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 184.

- Mbaku 200.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 51

- Nkolo, Jean-Victor, and Graeme Ewens (2000). "Cameroon: Music of a Small Continent". World Music, Volume 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. London: Rough Guides Ltd., p. 43, ISBN 1858286352.

- Keke, Reginald Chikere. "Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia Conflict: A Political Economy." Theory & Event 23.2 (2020): 329–351.

- West 84–5.

- Mbaku 121–2.

- Hudgens and Trillo 1047

- Mbaku 122

- West 84.

- Mbaku 121

- Hudgens and Trillo 1049.

- "Cameroon clothing – A description of the traditional attire of Cameroon". Cameroon-Today.com. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Culture and Customs of Cameroon, 2000, pg. 135, by, John Mukum Mbaku

- "Cameroon:Imane Ayissi detremined to project Cameroon's couture". 7 April 2020.

- West 17.

- Mbaku 110–3.

- Mulenga, Andrew (30 April 2010). "Cameroon's indomitable contemporary art". The Post. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Mbaku 80–1

- Fitzpatrick, Mary (2002). "Cameroon." Lonely Planet West Africa, 5th ed. China: Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd., p. 38

- Mbaku 77, 83–4

- Volet, Jean-Marie (10 November 2006). "Cameroon Literature at a glance Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine". Reading women writers and African literatures. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 119–20

- West 20.

- Mbaku 85–6.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 120.

- West 127.

- West 92–3, 127.

- Shearlaw, Maeve (20 November 2016). "Africa Women Cup of Nations kicks off in Cameroon". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016.

- "Africa Cricket Association". africacricket.com. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- "Cameroon NBA Players - RealGM". Basketball.realgm.com. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- Morgan, Emmanuel (21 January 2022). "The Fearsome, Quiet Champion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

References

- DeLancey, Mark W.; DeLancey, Mark Dike (2000). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810837751.

- Hudgens, Jim; Trillo, Richard (1999). West Africa: The Rough Guide (3rd ed.). London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1858284682.

- Mbaku, John Mukum (2005). Culture and Customs of Cameroon. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313332319.

- Neba, Aaron (1999). Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Bamenda: Neba Publishers.

- West, Ben (2004). Cameroon: The Bradt Travel Guide. Guilford, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-1841620787.

Further reading

- "Cameroon – Annual Report 2007". Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2007. . Reporters without Borders. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- "Cameroon". Archived from the original on 13 January 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2007. . Human Development Report 2006. United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). pp. 110–113.

- Fonge, Fuabeh P. (1997). Modernization without Development in Africa: Patterns of Change and Continuity in Post-Independence Cameroonian Public Service. Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press, Inc.

- MacDonald, Brian S. (1997). "Case Study 4: Cameroon", Military Spending in Developing Countries: How Much Is Too Much? McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Njeuma, Dorothy L. (no date). "Country Profiles: Cameroon". The Boston College Center for International Higher Education. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- Rechniewski, Elizabeth. "1947: Decolonisation in the Shadow of the Cold War: the Case of French Cameroon." Australian & New Zealand Journal of European Studies 9.3 (2017). online

- Sa'ah, Randy Joe (23 June 2006). "Cameroon girls battle 'breast ironing'". BBC News. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- Wright, Susannah, ed. (2006). Cameroon. Madrid: MTH Multimedia S.L.

- "World Economic and Financial Surveys". World Economic Outlook Database, International Monetary Fund. September 2006. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

External links

- Cameroon. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Cameroon Corruption Profile Archived 24 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine from Business Anti-Corruption Portal

- Cameroon from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Cameroon at Curlie

- Cameroon profile from the BBC News

Wikimedia Atlas of Cameroon

Wikimedia Atlas of Cameroon- Key Development Forecasts for Cameroon from International Futures

- Government

- Presidency of the Republic of Cameroon

- Prime Minister's Office

- National Assembly of Cameroon

- Global Integrity Report: Cameroon has reporting on anti-corruption in Cameroon

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- Trade

- Summary Trade Statistics from World Bank

.svg.png.webp)