Saka

The Saka (Old Persian:𐎿𐎣𐎠 Sakā; Kharoṣṭhī: 𐨯𐨐 Saka; Ancient Egyptian: 𓋴𓎝𓎡𓈉 sk, 𓐠𓎼𓈉 sꜣg; Chinese: 塞, old *Sək, mod. Sè, Sāi), Shaka (Sanskrit (Brāhmī): 𑀰𑀓, ![]()

![]() , Śaka; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): शक Śaka, शाक Śāka), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: Σάκαι Sákai; Latin: Sacae) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who historically inhabited the northern and eastern Eurasian Steppe and the Tarim Basin.[2][3]

, Śaka; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): शक Śaka, शाक Śāka), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: Σάκαι Sákai; Latin: Sacae) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who historically inhabited the northern and eastern Eurasian Steppe and the Tarim Basin.[2][3]

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Sakas were closely related to the European Scythians, and both groups formed part of the wider Scythian cultures[4] and ultimately derived from the earlier Andronovo culture, and the Saka language formed part of the Scythian languages. However, the Sakas of the Asian steppes are to be distinguished from the Scythians of the Pontic Steppe;[3][5] and although the ancient Persians, ancient Greeks, and ancient Babylonians respectively used the names "Saka," "Scythian," and "Cimmerian" for all the steppe nomads, the name "Saka" is used specifically for the ancient nomads of the eastern steppe while "Scythian" is used for the related group of nomads living in the western steppe;[3][6][7] and while the Cimmerians were often described by contemporaries as culturally Scythian, they may have differed ethnically from the Scythians proper, to whom the Cimmerians were related, and who also displaced and replaced the Cimmerians.[8]

Prominent archaeological remains of the Sakas include Arzhan,[9] Tunnug,[10] the Pazyryk burials,[11] the Issyk kurgan, Saka Kurgan tombs,[12] the Barrows of Tasmola[13] and possibly Tillya Tepe.

In the 2nd century BC, many Sakas were driven by the Yuezhi from the steppe into Sogdia and Bactria and then to the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, where they were known as the Indo-Scythians.[14][15][16] Other Sakas invaded the Parthian Empire, eventually settling in Sistan, while others may have migrated to the Dian Kingdom in Yunnan, China. In the Tarim Basin and Taklamakan Desert of today's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, they settled in Khotan, Yarkand, Kashgar and other places.[17]

Name

Etymology

Linguist Oswald Szemerényi studied synonyms of various origins for Scythian and differentiated the following terms: Sakā 𐎿𐎣𐎠, Skuthēs Σκύθης, Skudra 𐎿𐎤𐎢𐎭𐎼, and Sugᵘda 𐎿𐎢𐎦𐎢𐎭.[18]

Derived from an Iranian verbal root sak-, "go, roam" and thus meaning "nomad" was the term Sakā, from which came the names:

- Old Persian: 𐎿𐎣𐎠 Sakā, used by the ancient Persians to designate all nomads of the Eurasian steppe, including the Pontic Scythians[19]

- Ancient Greek: Σάκαι Sákai

- Latin: Sacae

- Sanskrit: शक Śaka

- Old Chinese: 塞 Sək[20][21][22] From the Indo-European root (s)kewd-, meaning "propel, shoot" (and from which was also derived the English word shoot), of which *skud- is the zero-grade form, was descended the Scythians' self-name reconstructed by Szemerényi as *Skuδa (roughly "archer"). From this were descended the following exonyms:

- Akkadian:

Iškuzaya and

Iškuzaya and

Askuzaya, used by the Assyrians

Askuzaya, used by the Assyrians - Old Persian: 𐎿𐎤𐎢𐎭𐎼 Skudra

- Ancient Greek: Σκύθης Skúthēs (plural Σκύθαι Skúthai), used by the Ancient Greeks[23]

- The Old Armenian: սկիւթ Skiwtʰ is based on itacistic Greek

A late Scythian sound change from /δ/ to /l/ resulted in the evolution of *Skuδa into *Skula. From this was derived the Greek word Skṓlotoi Σκώλοτοι, which, according to Herodotus, was the self-designation of the Royal Scythians.[24][25]

Identification

The name Sakā was used by the ancient Persian to refer to all the Iranian nomadic tribes living to the north of their empire, including both those who lived between the Caspian Sea and the Hungry steppe, and those who lived to the north of the Danube and the Black Sea. The Assyrians meanwhile called these nomads the Ishkuzai (Akkadian: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Iškuzaya[26][27]) or Askuzai (Akkadian:

Iškuzaya[26][27]) or Askuzai (Akkadian: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Asguzaya,

Asguzaya, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() mat Askuzaya,

mat Askuzaya, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() mat Ášguzaya[26][28]), and the Ancient Greeks called them Skuthai (Ancient Greek: Σκύθης Skúthēs, Σκύθοι Skúthoi, Σκύθαι Skúthai).[29]

mat Ášguzaya[26][28]), and the Ancient Greeks called them Skuthai (Ancient Greek: Σκύθης Skúthēs, Σκύθοι Skúthoi, Σκύθαι Skúthai).[29]

The Achaemenid inscriptions initially listed a single group of Sakā. However, following Darius I's campaign of 520 to 518 BC against the Asian nomads, they were differentiated into two groups, both living in Central Asia to the east of the Caspian Sea:[29][31]

- the Sakā tigraxaudā (𐎿𐎣𐎠 𐏐 𐎫𐎡𐎥𐎼𐎧𐎢𐎭𐎠) – "Sakā who wear pointed caps," who were also known as the Massagetae.[32][33]

- the Sakā haumavargā (𐎿𐎣𐎠 𐏐 𐏃𐎢𐎶𐎺𐎼𐎥𐎠) – interpreted as "Sakā who lay hauma (around the fire)",[34] which can be interpreted as "Saka who revere hauma."[35]

A third name was added after the Darius's campaign north of the Danube:[29]

- the Sakā tayaiy paradraya (𐎿𐎣𐎠 𐏐 𐎫𐎹𐎡𐎹 𐏐 𐎱𐎼𐎭𐎼𐎹) – "the Sakā who live beyond the (Black) Sea," who were the Pontic Scythians of the East European steppes

An additional term is found in two inscriptions elsewhere:[36][29]

- the Sakaibiš tayaiy para Sugdam (𐎿𐎣𐎡𐎲𐎡𐏁 𐏐 𐎫𐎹𐎡𐎹 𐏐 𐎱𐎼 𐏐 𐎿𐎢𐎥𐎭𐎶) – "Saka who are beyond Sogdia", a term was used by Darius for the people who formed the north-eastern limits of his empire at the opposite end to satrapy of Kush (the Ethiopians).[37][38] These Sakaibiš tayaiy para Sugdam have been suggested to have been the same people as the Sakā haumavargā[39]

Moreover, Darius the Great's Suez Inscriptions mention two group of Sakas:[40][41]

- the Sꜣg pḥ (𓐠𓎼𓄖𓈉) – "Sakā of the Marshes"

- the Sk tꜣ (𓋴𓎝𓎡𓇿𓈉) – "Sakā of the Land"

The scholar David Bivar had tentatively identified the Sk tꜣ with the Sakā haumavargā,[42] and John Manuel Cook had tentatively identified the Sꜣg pḥ with the Sakā tigraxaudā.[39] More recently, the scholar Rüdiger Schmitt has suggested that the Sꜣg pḥ and the Sk tꜣ might have collectively designated the Sakā tigraxaudā/Massagetae.[43]

The Achaemenid king Xerxes I listed the Saka coupled with the Dahā (𐎭𐏃𐎠) people of Central Asia,[37][39][36] who might possibly have been identical with the Sakā tigraxaudā.[44][45][46]

Modern terminology

Although the ancient Persians, ancient Greeks, and ancient Babylonians respectively used the names "Saka," "Scythian," and "Cimmerian" for all the steppe nomads, modern scholars now use the term Saka to refer specifically to Iranian peoples who inhabited the northern and eastern Eurasian Steppe and the Tarim Basin;[2][47][3][7] and while the Cimmerians were often described by contemporaries as culturally Scythian, they may have differed ethnically from the Scythians proper, to whom the Cimmerians were related, and who also displaced and replaced the Cimmerians.[8]

Location

The Sakā tigraxaudā and Sakā haumavargā both lived in the steppe and highland areas located in northern Central Asia and to the east of the Caspian Sea.[29][31][54]

The Sakā tigraxaudā/Massagetae more specifically lived around Chorasmia[55] and in the lowlands of Central Asia located to the east of the Caspian Sea and the south-east of the Aral Sea, in the Kyzylkum Desert and the Ustyurt Plateau, most especially between the Araxes and Iaxartes rivers.[44][43] The Sakā tigraxaudā/Massagetae could also be found in the Caspian Steppe.[32] The imprecise description of where the Massagetae lived by ancient authors has however led modern scholars to ascribe to them various locations, such as the Oxus delta, the Iaxartes delta, between the Caspian and Aral seas or forther to the north or north-east, but without basing these suggestions on any conclusive arguments.[43] Other locations assigned to the Massagetae include the area corresponding to modern-day Turkmenistan.[56]

The Sakā haumavargā lived around the Pamir Mountains and the Ferghana Valley.[55]

The Sakaibiš tayaiy para Sugdam, who may have been identical with the Sakā haumavargā, lived on the north-east border of the Achaemenid Empire on the Iaxartes river.[29]

Some other Saka groups lived to the east of the Pamir Mountains and to the north of the Iaxartes river,[54] as well as in the regions corresponding to modern-day Qirghizia, Tian Shan, Altai, Tuva, Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Kazakhstan.[55]

The Sək, that is the Saka who were in contact with the Chinese, inhabited the Ili and Chu valleys of modern Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, which was called the "land of the Sək", i.e. "land of the Saka", in the Book of Han.[57]

History

Origins

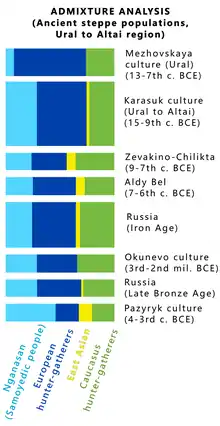

Recent archeological and genetic data suggests that the Western and Eastern Scythians of the 1st millennium BC originated independently, but both combine Yamnaya-related ancestry, which spread eastwards from the area of the European steppes,[58] with an East Asian-related component, which most closely corresponds to the modern North Siberian Nganasan people of the lower Yenisey River, to varying degrees, but generally higher among Eastern Scythians.[58]

On the other hand, archaeological evidence now tends to suggest that the origins of Scythian culture, characterized by its kurgans burial mounds and its Animal style of the 1st millennium BC, are to be found among Eastern Scythians rather than their Western counterparts: eastern kurgans are older than western ones (such as the Altaic kurgan Arzhan 1 in Tuva), and elements of the Animal style are first attested in areas of the Yenisei river and modern-day China in the 10th century CE.[59] The rapid spread of Scythian culture, from the Eastern Scythians to the Western Scythians, is also confirmed by significant east-to-west gene flow across the steppes during the 1st millennium BC.[58][59]

The Sakas spoke a language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages. The Pazyryk burials of the Pazyryk culture in the Ukok Plateau in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC are thought to be of Saka chieftains.[60][61][62] These burials show striking similarities with the earlier Tarim mummies at Gumugou.[61] The Issyk kurgan of south-eastern Kazakhstan,[62] and the Ordos culture of the Ordos Plateau has also been connected with the Saka.[63] It has been suggested that the ruling elite of the Xiongnu was of Saka origin.[64] Some scholars contend that in the 8th century BC, a Saka raid on Altai may be "connected" with a raid on Zhou China.[65]

Early history

The Saka are attested in historical and archaeological records dating to around the 8th century BC.[66]

The Saka tribe of the Massagetae/Tigraxaudā rose to power in the 8th to 7th centuries BC, when they migrated from the east into Central Asia,[43] from where they expelled the Scythians, another nomadic Iranian tribe to whom they were closely related, after which they came to occupy large areas of the region beginning in the 6th century BC.[32] The Massagetae forcing the Early Scythians to the west across the Araxes river and into the Caucasian and Pontic steppes started a significant movement of the nomadic peoples of the Eurasian Steppe,[67] following which the Scythians displaced the Cimmerians and the Agathyrsi, who were also nomadic Iranian peoples closely related to the Massagetae and the Scythians, conquered their territories,[67][68][32][69][70][71] and invaded Western Asia, where their presence had an important role in the history of the ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Egypt, and Iran.[69]

During the 7th century BC itself, Saka presence started appearing in the Tarim Basin region.[66]

According to the ancient Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, the Parthians rebelled against the Medes during the reign of Cyaxares, after which the Parthians put their country and capital city under the protection of the Sakas. This was followed by a long war opposing the Medes to the Saka, the latter of whom were led by the queen Zarinaea. At the end of this war, the Parthians accepted Median rule, and the Saka and the Medes made peace.[72][73][74]

According to the Greek historian Ctesias, once the Persian Achaemenid Empire's founder, Cyrus, had overthrown his grandfather the Median king Astyages, the Bactrians accepted him as the heir of Astyages and submitted to him, after which he founded the city of Cyropolis on the Iaxartes river as well as seven fortresses to protect the northern frontier of his empire against the Saka. Cyrus then attacked the Sakā haumavargā, initially defeated them and captured their king, Amorges. After this, Amorges's queen, Sparethra, defeated Cyrus with a large army of both men and women warriors and captured Parmises, the brother-in-law of Cyrus and the brother of his wife Amytis, as well as Parmises's three sons, whom Sparethra exchanged in return for her husband, after which Cyrus and Amorges became allies, and Amorges helped Cyrus conquer Lydia.[75][76][77][78][79][80]

Cyrus, accompanied by the Sakā haumavargā of his ally Amorges, later carried out a campaign against the Massagetae/Sakā tigraxaudā in 530 BC.[43] According to Herodotus, Cyrus captured a Massagetaean camp by ruse, after which the Massagetae queen Tomyris led the tribe's main force against the Persians, defeated them, and placed the severed head of Cyrus in a sack full of blood. Some versions of the records of the death of Cyrus named the Derbices, rather than the Massagetae, as the tribe against whom Cyrus died in battle, because the Derbices were a member tribe of the Massagetae confederation or identical with the whole of the Massagetae.[81][43] After Cyrus had been mortally wounded by the Derbices/Massagetae, Amorges and his Sakā haumavargā army helped the Persian soldiers defeat them. Cyrus told his sons to respect their own mother as well as Amorges above everyone else before dying.[80]

Possibly shortly before the 520s BC, the Saka expanded into the valleys of the Ili and Chu in eastern Central Asia.[57] Around 30 Saka tombs in the form of kurgans (burial mounds) have also been found in the Tian Shan area dated to between 550–250 BC.[66]

Darius I waged wars against the eastern Sakas during a campaign of 520 to 518 BC where, according to his inscription at Behistun, he conquered the Massagetae/Sakā tigraxaudā, captured their king Skunxa, and replaced him with a ruler who was loyal to Achaemenid rule.[43][80][82] The territories of the Saka were absorbed into the Achaemenid Empire as part of Chorasmia that included much of the territory between the Oxus and the Iaxartes rivers,[83] and the Saka then supplied the Achaemenid army with large number of mounted bowmen.[84] According to Polyaenus, Darius fought against three armies led by three kings, respectively named Sacesphares, Amorges or Homarges, and Thamyris, with Polyaenus's account being based on accurate Persian historical records.[80][85][86] After Darius's administrative reforms of the Achaemenid Empire, the Sakā tigraxaudā were included within the same tax district as the Medes.[87]

During the period of Achaemenid rule, Central Asia was in contact with Saka populations who were themselves in contact with China.[88]

After Alexander the Great conquered the Achaemenid Empire, the Saka resisted his incursions into Central Asia.[47]

At least by the late 2nd century BC, the Sakas had founded states in the Tarim Basin.[17]

Migrations

The Saka were pushed out of the Ili and Chu River valleys by the Yuezhi.[89][14][15] An account of the movement of these people is given in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian. The Yuehzhi, who originally lived between Tängri Tagh (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang of Gansu, China,[90] were assaulted and forced to flee from the Hexi Corridor of Gansu by the forces of the Xiongnu ruler Modu Chanyu, who conquered the area in 177–176 BC.[91][92][93][94][95][96] In turn the Yuehzhi were responsible for attacking and pushing the Sai (i.e. Saka) west into Sogdiana, where, between 140 and 130 BC, the latter crossed the Syr Darya into Bactria. The Saka also moved southwards toward the Pamirs and northern India, where they settled in Kashmir, and eastward, to settle in some of the oasis-states of Tarim Basin sites, like Yanqi (焉耆, Karasahr) and Qiuci (龜茲, Kucha).[97][98] The Yuehzhi, themselves under attacks from another nomadic tribe, the Wusun, in 133–132 BC, moved, again, from the Ili and Chu valleys, and occupied the country of Daxia, (大夏, "Bactria").[57][99]

The ancient Greco-Roman geographer Strabo noted that the four tribes that took down the Bactrians in the Greek and Roman account – the Asioi, Pasianoi, Tokharoi and Sakaraulai – came from land north of the Syr Darya where the Ili and Chu valleys are located.[100][57] Identification of these four tribes varies, but Sakaraulai may indicate an ancient Saka tribe, the Tokharoi is possibly the Yuezhi, and while the Asioi had been proposed to be groups such as the Wusun or Alans.[100][101]

René Grousset wrote of the migration of the Saka: "the Saka, under pressure from the Yueh-chih [Yuezhi], overran Sogdiana and then Bactria, there taking the place of the Greeks." Then, "Thrust back in the south by the Yueh-chih," the Saka occupied "the Saka country, Sakastana, whence the modern Persian Seistan."[100] Some of the Saka fleeing the Yuezhi attacked the Parthian Empire, where they defeated and killed the kings Phraates II and Artabanus.[89] These Sakas were eventually settled by Mithridates II in what become known as Sakastan.[89] According to Harold Walter Bailey, the territory of Drangiana (now in Afghanistan and Pakistan) became known as "Land of the Sakas", and was called Sakastāna in the Persian language of contemporary Iran, in Armenian as Sakastan, with similar equivalents in Pahlavi, Greek, Sogdian, Syriac, Arabic, and the Middle Persian tongue used in Turfan, Xinjiang, China.[102] This is attested in a contemporary Kharosthi inscription found on the Mathura lion capital belonging to the Saka kingdom of the Indo-Scythians (200 BC – 400 AD) in North India,[102] roughly the same time the Chinese record that the Saka had invaded and settled the country of Jibin 罽賓 (i.e. Kashmir, of modern-day India and Pakistan).[103]

Iaroslav Lebedynsky and Victor H. Mair speculate that some Sakas may also have migrated to the area of Yunnan in southern China following their expulsion by the Yuezhi. Excavations of the prehistoric art of the Dian Kingdom of Yunnan have revealed hunting scenes of Caucasoid horsemen in Central Asian clothing.[104] The scenes depicted on these drums sometimes represent these horsemen practising hunting. Animal scenes of felines attacking oxen are also at times reminiscent of Scythian art both in theme and in composition.[105]

Migrations of the 2nd and 1st century BC have left traces in Sogdia and Bactria, but they cannot firmly be attributed to the Saka, similarly with the sites of Sirkap and Taxila in ancient India. The rich graves at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan are seen as part of a population affected by the Saka.[106]

The Shakya clan of India, to which Gautama Buddha, called Śākyamuni "Sage of the Shakyas", belonged, were also likely Sakas, as Michael Witzel[107] and Christopher I. Beckwith[108] have demonstrated.

Indo-Scythians

The region in modern Afghanistan and Iran where the Saka moved to became known as "land of the Saka" or Sakastan.[102] This is attested in a contemporary Kharosthi inscription found on the Mathura lion capital belonging to the Saka kingdom of the Indo-Scythians (200 BC – 400 AD) in northern India,[102] roughly the same time the Chinese record that the Saka had invaded and settled the country of Jibin 罽賓 (i.e. Kashmir, of modern-day India and Pakistan).[103] In the Persian language of contemporary Iran the territory of Drangiana was called Sakastāna, in Armenian as Sakastan, with similar equivalents in Pahlavi, Greek, Sogdian, Syriac, Arabic, and the Middle Persian tongue used in Turfan, Xinjiang, China.[102] The Sakas also captured Gandhara and Taxila, and migrated to North India.[112] The most famous Indo-Scythian king was Maues.[113] An Indo-Scythians kingdom was established in Mathura (200 BC – 400 AD).[102][16] Weer Rajendra Rishi, an Indian linguist, identified linguistic affinities between Indian and Central Asian languages, which further lends credence to the possibility of historical Sakan influence in North India.[112][114] According to historian Michael Mitchiner, the Abhira tribe were a Saka people cited in the Gunda inscription of the Western Satrap Rudrasimha I dated to AD 181.[115]

Kingdom of Khotan

Obv: Kharosthi legend, "Of the great king of kings, king of Khotan, Gurgamoya.

Rev: Chinese legend: "Twenty-four grain copper coin". British Museum

The Kingdom of Khotan was a Saka city state in on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin. As a consequence of the Han–Xiongnu War spanning from 133 BC to 89 AD, the Tarim Basin (now Xinjiang, Northwest China), including Khotan and Kashgar, fell under Han Chinese influence, beginning with the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BC).[116][117]

Archaeological evidence and documents from Khotan and other sites in the Tarim Basin provided information on the language spoken by the Saka.[102]>[118] The official language of Khotan was initially Gandhari Prakrit written in Kharosthi, and coins from Khotan dated to the 1st century bear dual inscriptions in Chinese and Gandhari Prakrit, indicating links of Khotan to both India and China.[119] Surviving documents however suggest that an Iranian language was used by the people of the kingdom for a long time Third-century AD documents in Prakrit from nearby Shanshan record the title for the king of Khotan as hinajha (i.e. "generalissimo"), a distinctively Iranian-based word equivalent to the Sanskrit title senapati, yet nearly identical to the Khotanese Saka hīnāysa attested in later Khotanese documents.[119] This, along with the fact that the king's recorded regnal periods were given as the Khotanese kṣuṇa, "implies an established connection between the Iranian inhabitants and the royal power," according to the Professor of Iranian Studies Ronald E. Emmerick.[119] He contended that Khotanese-Saka-language royal rescripts of Khotan dated to the 10th century "makes it likely that the ruler of Khotan was a speaker of Iranian."[119] Furthermore, he argued that the early form of the name of Khotan, hvatana, is connected semantically with the name Saka.[119]

The region once again came under Chinese suzerainty with the campaigns of conquest by Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626–649).[120] From the late eighth to ninth centuries, the region changed hands between the rival Tang and Tibetan Empires.[121][122] However, by the early 11th century the region fell to the Muslim Turkic peoples of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, which led to both the Turkification of the region as well as its conversion from Buddhism to Islam.

Later Khotanese-Saka-language documents, ranging from medical texts to Buddhist literature, have been found in Khotan and Tumshuq (northeast of Kashgar).[102] Similar documents in the Khotanese-Saka language dating mostly to the 10th century have been found in the Dunhuang manuscripts.[123]

Although the ancient Chinese had called Khotan Yutian (于闐), another more native Iranian name occasionally used was Jusadanna (瞿薩旦那), derived from Indo-Iranian Gostan and Gostana, the names of the town and region around it, respectively.[124]

Shule Kingdom

Much like the neighboring people of the Kingdom of Khotan, people of Kashgar, the capital of Shule, spoke Saka, one of the Eastern Iranian languages.[125] According to the Book of Han, the Saka split and formed several states in the region. These Saka states may include two states to the northwest of Kashgar, and Tumshuq to its northeast, and Tushkurgan south in the Pamirs.[126] Kashgar also conquered other states such as Yarkand and Kucha during the Han dynasty, but in its later history, Kashgar was controlled by various empires, including Tang China,[127][128][129] before it became part of the Turkic Kara-Khanid Khanate in the 10th century. In the 11th century, according to Mahmud al-Kashgari, some non-Turkic languages like the Kanchaki and Sogdian were still used in some areas in the vicinity of Kashgar,[130] and Kanchaki is thought to belong to the Saka language group.[126] It is believed that the Tarim Basin was linguistically Turkified before the 11th century ended.[131]

Historiography

Persians referred to all northern nomads as Sakas. Herodotus (IV.64) describes them as Scythians, although they figure under a different name:

The Sacae, or Scyths, were clad in trousers, and had on their heads tall stiff caps rising to a point. They bore the bow of their country and the dagger; besides which they carried the battle-axe, or sagaris. They were in truth Amyrgian (Western) Scythians, but the Persians called them Sacae, since that is the name which they gave to all Scythians.

Strabo

In the 1st century BC, the Greek-Roman geographer Strabo gave an extensive description of the peoples of the eastern steppe, whom he located in Central Asia beyond Bactria and Sogdiana.[132]

Strabo went on to list the names of the various tribes he believed to be "Scythian",[132] and in so doing almost certainly conflated them with unrelated tribes of eastern Central Asia. These tribes included the Saka.

Now the greater part of the Scythians, beginning at the Caspian Sea, are called Däae, but those who are situated more to the east than these are named Massagetae and Sacae, whereas all the rest are given the general name of Scythians, though each people is given a separate name of its own. They are all for the most part nomads. But the best known of the nomads are those who took away Bactriana from the Greeks, I mean the Asii, Pasiani, Tochari, and Sacarauli, who originally came from the country on the other side of the Iaxartes River that adjoins that of the Sacae and the Sogdiani and was occupied by the Sacae. And as for the Däae, some of them are called Aparni, some Xanthii, and some Pissuri. Now of these the Aparni are situated closest to Hyrcania and the part of the sea that borders on it, but the remainder extend even as far as the country that stretches parallel to Aria. Between them and Hyrcania and Parthia and extending as far as the Arians is a great waterless desert, which they traversed by long marches and then overran Hyrcania, Nesaea, and the plains of the Parthians. And these people agreed to pay tribute, and the tribute was to allow the invaders at certain appointed times to overrun the country and carry off booty. But when the invaders overran their country more than the agreement allowed, war ensued, and in turn their quarrels were composed and new wars were begun. Such is the life of the other nomads also, who are always attacking their neighbors and then in turn settling their differences.

- (Strabo, Geography, 11.8.1; transl. 1903 by H. C. Hamilton & W. Falconer.)[132]

Indian sources

The Sakas receive numerous mentions in Indian texts, including the Purāṇas, the Manusmṛiti, the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata, and the Mahābhāṣya of Patanjali.

Language

Modern scholarly consensus is that the Eastern Iranian language ancestral to the Pamir languages in Central Asia and the medieval Saka language of Xinjiang, was one of the Scythian languages.[133] Evidence of the Middle Iranian "Scytho-Khotanese" language survives in Northwest China, where Khotanese-Saka-language documents, ranging from medical texts to Buddhist texts, have been found primarily in Khotan and Tumshuq (northeast of Kashgar).[102] They largely predate the Islamization of Xinjiang under the Turkic-speaking Kara-Khanid Khanate.[102] Similar documents, the Dunhuang manuscripts, were discovered written in the Khotanese Saka language and date mostly from the tenth century.[134]

Attestations of the Saka language show that it was an Eastern Iranian language. The linguistic heartland of Saka was the Kingdom of Khotan, which had two varieties, corresponding to the major settlements at Khotan (now called Hotan) and Tumshuq (now titled Tumxuk).[135][136] Tumshuqese and Khotanese varieties of Saka contain many borrowings from the Middle Indo-Aryan languages, but also share features with the modern Eastern Iranian languages Wakhi and Pashto.[137]

The Issyk inscription, a short fragment on a silver cup found in the Issyk kurgan in Kazakhstan is believed to be an early example of Saka, constituting one of very few autochthonous epigraphic traces of that language. The inscription is in a variant of Kharosthi. Harmatta identifies the dialect as Khotanese Saka, tentatively translating its as: "The vessel should hold wine of grapes, added cooked food, so much, to the mortal, then added cooked fresh butter on".[138]

A growing body of both linguistic and physical anthropological evidence suggest the Wakhi are descendants of Saka.[139][140][141][142][143][144] According to the Indo-Europeanist Martin Kümmel, Wakhi may be classified as a Western Saka dialect; the other attested Saka dialects, Khotanese and Tumshuqese, would then be classified as Eastern Saka.[145]

The Saka heartland was gradually conquered during the Turkic expansion, beginning in the sixth century, and the area was gradually Turkified linguistically under the Uyghurs.

Genetics

The earliest studies could only analyze segments of mtDNA, thus providing only broad correlations of affinity to modern West Eurasian or East Eurasian populations. For example, in a 2002 study the mitochondrial DNA of Saka period male and female skeletal remains from a double inhumation kurgan at the Beral site in Kazakhstan was analysed. The two individuals were found to be not closely related. The HV1 mitochondrial sequence of the male was similar to the Anderson sequence which is most frequent in European populations. The HV1 sequence of the female suggested a greater likelihood of Asian origins.[146]

More recent studies have been able to type for specific mtDNA lineages. For example, a 2004 study examined the HV1 sequence obtained from a male "Scytho-Siberian" at the Kizil site in the Altai Republic. It belonged to the N1a maternal lineage, a geographically West Eurasian lineage.[148] Another study by the same team, again of mtDNA from two Scytho-Siberian skeletons found in the Altai Republic, showed that they had been typical males "of mixed Euro-Mongoloid origin". One of the individuals was found to carry the F2a maternal lineage, and the other the D lineage, both of which are characteristic of East Eurasian populations.[149]

These early studies have been elaborated by an increasing number of studies by Russian scholars. Conclusions are (i) an early, Bronze Age mixing of both west and east Eurasian lineages, with western lineages being found far to the east, but not vice versa; (ii) an apparent reversal by Iron Age times, with an increasing presence of East Eurasian lineages in the western steppe; (iii) the possible role of migrations from the south, the Balkano-Danubian and Iranian regions, toward the steppe.[150]

Ancient Y-DNA data was finally provided by Keyser et al in 2009. They studied the haplotypes and haplogroups of 26 ancient human specimens from the Krasnoyarsk area in Siberia dated from between the middle of the 2nd millennium BC and the 4th century AD (Scythian and Sarmatian timeframe). Nearly all subjects belonged to haplogroup R-M17. The authors suggest that their data shows that between the Bronze and the Iron Ages the constellation of populations known variously as Scythians, Andronovians, etc. were blue- (or green-) eyed, fair-skinned and light-haired people who might have played a role in the early development of the Tarim Basin civilisation. Moreover, this study found that they were genetically more closely related to modern populations in eastern Europe than those of central and southern Asia.[151] The ubiquity and dominance of the R1a Y-DNA lineage contrasted markedly with the diversity seen in the mtDNA profiles.

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of twenty-eight Sakas buried between ca. 900 BC to AD 1, compromising eight Sakas of southern Siberia (Tagar culture), eight Sakas of the central steppe (Tasmola culture), and twelve Sakas of the Tian Shan. The six samples of Y-DNA extracted from the Tian Shan Saka belonged to the haplogroups R (four samples), R1 and R1a1. The samples of mtDNA extracted from the Tien Shan Saka belonged to C4, H4d, T2a1, U5a1d2b, H2a, U5a1a1, HV6 (two samples), D4j8 (two samples), W1c and G2a1. The study detected significant genetic differences between the Sakas and Scythians of the Pannonian Basin, and between Sakas of southern Siberia, the central steppe and the Tian Shan. Tian Shan Sakas were found to be of about 70% Western Steppe Herder (WSH) ancestry, 25% Siberian Hunter-Gatherer ancestry and 5% Iranian Neolithic ancestry. The Iranian Neolithic ancestry was primarily male-derived, probably from the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex. Sakas of the Tasmola culture were found to be of about 56% WSH ancestry and 44% Siberian Hunter-Gather ancestry. The peoples of the Tagar culture had about 83.5% WSH ancestry, 9% Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) ancestry and 7.5% Siberian Hunter-Gatherer ancestry. The study suggested that the Saka were the source of west Eurasian ancestry among the Xiongnu, and that the Huns probably emerged through minor male-driven East Asian geneflow into the Saka through westward migrations by the Xiongnu.[152]

Physical appearance

Early physical analyses have unanimously concluded that the Saka, even those far to the east (e.g. the Pazyryk region), possessed predominantly "Europid" features, although mixed "Euro-Mongoloid" phenotypes also occur, depending on site and period.[153]

The 2nd century BC Han Chinese envoy Zhang Qian described the Sai (Saka) as having yellow (probably meaning hazel or green), and blue eyes.[154] In Natural History, the 1st century AD Roman author Pliny the Elder characterises the Seres, sometimes identified as Saka or Tocharians, as red-haired and blue-eyed.[154][155]

Archaeology

The spectacular grave-goods from Arzhan, and others in Tuva, have been dated from about 900 BC onward, and are associated with the Saka. Burials at Pazyryk in the Altay Mountains have included some spectacularly preserved Sakas of the "Pazyryk culture" – including the Ice Maiden of the 5th century BC.

Pazyryk culture

Saka burials documented by modern archaeologists include the kurgans at Pazyryk in the Ulagan (Red) district of the Altai Republic, south of Novosibirsk in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia (near Mongolia). Archaeologists have extrapolated the Pazyryk culture from these finds: five large burial mounds and several smaller ones between 1925 and 1949, one opened in 1947 by Russian archaeologist Sergei Rudenko. The burial mounds concealed chambers of larch-logs covered over with large cairns of boulders and stones.[157]

The Pazyryk culture flourished between the 7th and 3rd century BC in the area associated with the Sacae.

Ordinary Pazyryk graves contain only common utensils, but in one, among other treasures, archaeologists found the famous Pazyryk Carpet, the oldest surviving wool-pile oriental rug. Another striking find, a 3-metre-high four-wheel funerary chariot, survived well-preserved from the 5th to 4th century BC.[158]

Tillia Tepe treasure

A site found in 1968 in Tillia Tepe (literally "the golden hill") in northern Afghanistan (former Bactria) near Shebergan consisted of the graves of five women and one man with extremely rich jewelry, dated to around the 1st century BC, and probably related to that of Saka tribes normally living slightly to the north. Altogether the graves yielded several thousands of pieces of fine jewelry, usually made from combinations of gold, turquoise and lapis-lazuli.

A high degree of cultural syncretism pervades the findings, however. Hellenistic cultural and artistic influences appear in many of the forms and human depictions (from amorini to rings with the depiction of Athena and her name inscribed in Greek), attributable to the existence of the Seleucid empire and Greco-Bactrian kingdom in the same area until around 140 BC, and the continued existence of the Indo-Greek kingdom in the northwestern Indian sub-continent until the beginning of our era. This testifies to the richness of cultural influences in the area of Bactria at that time.

Eleke Sazy Burial Complex

In 2020, archaeologists excavated multiple burial mounds in the Eleke Sazy Valley in East Kazakhstan. Here, a large number of gold artifacts were found. These artifacts included golf harness fittings, pendants, chains, appliqués, and more - most of which are in the Animal Style of the Scythian-Saka era dating back to the 5th-4th centuries BC.[159]

Culture

Art

The art of the Saka was of a similar styles as other Iranian peoples of the steppes, which is referred to collectively as Scythian art. In 2001, the discovery of an undisturbed royal Scythian burial-barrow illustrated Scythian animal-style gold that lacks the direct influence of Greek styles. Forty-four pounds of gold weighed down the royal couple in this burial, discovered near Kyzyl, capital of the Siberian republic of Tuva.

Ancient influences from Central Asia became identifiable in China following contacts of metropolitan China with nomadic western and northwestern border territories from the 8th century BC. The Chinese adopted the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes (descriptions of animals locked in combat), particularly the rectangular belt-plaques made of gold or bronze, and created their own versions in jade and steatite.[160]

Following their expulsion by the Yuezhi, some Saka may also have migrated to the area of Yunnan in southern China. Saka warriors could also have served as mercenaries for the various kingdoms of ancient China. Excavations of the prehistoric art of the Dian civilisation of Yunnan have revealed hunting scenes of Caucasoid horsemen in Central Asian clothing.[161]

Saka influences have been identified as far as Korea and Japan. Various Korean artifacts, such as the royal crowns of the kingdom of Silla, are said to be of "Scythian" design.[162] Similar crowns, brought through contacts with the continent, can also be found in Kofun era Japan.[163]

Clothing

Similar to other eastern Iranian peoples represented on the reliefs of the Apadāna at Persepolis, Sakas are depicted as wearing long trousers, which cover the uppers of their boots. Over their shoulders they trail a type of long mantle, with one diagonal edge in back. One particular tribe of Sakas (the Saka tigraxaudā) wore pointed caps. Herodotus in his description of the Persian army mentions the Sakas as wearing trousers and tall pointed caps.[164]

Herodotus says Sakas had "high caps tapering to a point and stiffly upright." Asian Saka headgear is clearly visible on the Persepolis Apadana staircase bas-relief – high pointed hat with flaps over ears and the nape of the neck.[167] From China to the Danube delta, men seemed to have worn a variety of soft headgear – either conical like the one described by Herodotus, or rounder, more like a Phrygian cap.

Saka women dressed in much the same fashion as men. A Pazyryk burial, discovered in the 1990s, contained the skeletons of a man and a woman, each with weapons, arrowheads, and an axe. Herodotus mentioned that Sakas had "high caps and … wore trousers." Clothing was sewn from plain-weave wool, hemp cloth, silk fabrics, felt, leather and hides.

Pazyryk findings give the most almost fully preserved garments and clothing worn by the Scythian/Saka peoples. Ancient Persian bas-reliefs, inscriptions from Apadana and Behistun and archaeological findings give visual representations of these garments.

Based on the Pazyryk findings (can be seen also in the south Siberian, Uralic and Kazakhstan rock drawings) some caps were topped with zoomorphic wooden sculptures firmly attached to a cap and forming an integral part of the headgear, similar to the surviving nomad helmets from northern China. Men and warrior women wore tunics, often embroidered, adorned with felt applique work, or metal (golden) plaques.

Persepolis Apadana again serves a good starting point to observe the tunics of the Sakas. They appear to be a sewn, long-sleeved garment that extended to the knees and was girded with a belt, while the owner's weapons were fastened to the belt (sword or dagger, gorytos, battle-axe, whetstone etc.). Based on numerous archeological findings, men and warrior women wore long-sleeved tunics that were always belted, often with richly ornamented belts. The Kazakhstan Saka (e.g. Issyk Golden Man/Maiden) wore shorter and closer-fitting tunics than the Pontic steppe Scythians. Some Pazyryk culture Saka wore short belted tunic with a lapel on the right side, with upright collar, 'puffed' sleeves narrowing at the wrist and bound in narrow cuffs of a color different from the rest of the tunic.

Men and women wore coats: e.g. Pazyryk Saka had many varieties, from fur to felt. They could have worn a riding coat that later was known as a Median robe or Kantus. Long sleeved, and open, it seems that on the Persepolis Apadana Skudrian delegation is perhaps shown wearing such coat. The Pazyryk felt tapestry shows a rider wearing a billowing cloak.

See also

- Besshatyr Burial Ground

- History of the central steppe

- Sakas in the Mahabharata

- Sakzai

- Shaka era

- Sagetae

References

Citations

- Chang, Claudia (2017). Rethinking Prehistoric Central Asia: Shepherds, Farmers, and Nomads. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-351-70158-7.

- Beckwith 2009, p. 68 "Modern scholars have mostly used the name Saka to refer specifically to Iranians of the Eastern Steppe and Tarim Basin"

- Dandamayev 1994, p. 37 "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan to distinguish them from the related Massagetae of the Aral region and the Scythians of the Pontic steppes. These tribes spoke Iranian languages, and their chief occupation was nomadic pastoralism."

- Unterländer et al. 2017: "During the first millennium BC, nomadic people spread over the Eurasian Steppe from the Altai Mountains over the northern Black Sea area as far as the Carpathian Basin... Greek and Persian historians of the 1st millennium BCE chronicle the existence of the Massagetae and Sauromatians, and later, the Sarmatians and Sacae: cultures possessing artefacts similar to those found in classical Scythian monuments, such as weapons, horse harnesses and a distinctive ‘Animal Style' artistic tradition. Accordingly, these groups are often assigned to the Scythian culture..."

- Kramrisch, Stella. "Central Asian Arts: Nomadic Cultures". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

The Śaka tribe was pasturing its herds in the Pamirs, central Tien Shan, and in the Amu Darya delta. Their gold belt buckles, jewelry, and harness decorations display sheep, griffins, and other animal designs that are similar in style to those used by the Scythians, a nomadic people living in the Kuban basin of the Caucasus region and the western section of the Eurasian plain during the greater part of the 1st millennium bc.

- David & McNiven 2018: "Horse-riding nomadism has been referred to as the culture of 'Early Nomads'. This term encompasses different ethnic groups (such as Scythians, Saka, Massagetae, and Yuezhi)..."

- Diakonoff 1985: the Persians called "Saka" all the northern nomads, just as the Greeks called them "Scythians", and the Babylonians "Cimmerians".

- Tokhtas’ev, Sergei R. (1991). "Cimmerians". Encyclopædia Iranica.

As the Cimmerians cannot be differentiated archeologically from the Scythians, it is possible to speculate about their Iranian origins. In the Neo-Babylonian texts (according to D’yakonov, including at least some of the Assyrian texts in Babylonian dialect) Gimirri and similar forms designate the Scythians and Central Asian Saka, reflecting the perception among inhabitants of Mesopotamia that Cimmerians and Scythians represented a single cultural and economic group

- Zaitseva, G. I.; Chugunov, K. V.; Alekseev, A. Yu; Dergachev, V. A.; Vasiliev, S. S.; Sementsov, A. A.; Cook, G.; Scott, E. M.; Plicht, J. van der; Parzinger, H.; Nagler, A. (2007). "Chronology of Key Barrows Belonging to Different Stages of the Scythian Period in Tuva (Arzhan-1 and Arzhan-2 Barrows)". Radiocarbon. 49 (2): 645–658. doi:10.1017/S0033822200042545. ISSN 0033-8222.

- Caspari, Gino; Sadykov, Timur; Blochin, Jegor; Hajdas, Irka (2018-09-01). "Tunnug 1 (Arzhan 0) – an early Scythian kurgan in Tuva Republic, Russia". Archaeological Research in Asia. 15: 82–87. doi:10.1016/j.ara.2017.11.001. ISSN 2352-2267. S2CID 135231553.

- Dergachev, V. A.; Vasiliev, S. S.; Sementsov, A. A.; Zaitseva, G. I.; Chugunov, K. A.; Sljusarenko, I. Ju (2001). "Dendrochronology and Radiocarbon Dating Methods in Archaeological Studies of Scythian Sites". Radiocarbon. 43 (2A): 417–424. doi:10.1017/S0033822200038273. ISSN 0033-8222.

- Panyushkina, Irina; Grigoriev, Fedor; Lange, Todd; Alimbay, Nursan (2013). "Radiocarbon and Tree-Ring Dates of the Bes-Shatyr #3 Saka Kurgan in the Semirechiye, Kazakhstan". Radiocarbon. 55 (3): 1297–1303. doi:10.1017/S0033822200048207. hdl:10150/628658. ISSN 0033-8222. S2CID 220661798.

- Beisenov, Àrman Z.; Duisenbay, Daniyar; Akhiyarov, Islam; Sargizova, Gulzada (2016-10-01). "Dromos Burials of Tasmola Culture in Central Kazakhstan". The Anthropologist. 26 (1–2): 25–33. doi:10.1080/09720073.2016.11892125. ISSN 0972-0073. S2CID 80362028.

- Benjamin, Craig (March 2003). "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia". Ērān ud Anērān Webfestschrift Marshak. Archived from the original on 2015-02-18. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- "Chinese History – Sai 塞 The Saka People or Soghdians". Chinaknowledge. Archived from the original on 2015-01-19. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- Beckwith 2009, p. 85 "The Saka, or Śaka, people then began their long migration that ended with their conquest of northern India, where they are also known as the Indo-Scythians."

- Sinor 1990, pp. 173–174

- Szemerényi, Oswald (1980). Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian – Skudra – Sogdian – Saka (PDF). Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 0-520-06864-5.

- West, Stephanie (2002). "Scythians". In Bakker, Egbert J.; de Jong, Irene J. F.; van Wees, Hans (eds.). Brill's Companion to Herodotus. Brill. pp. 437–456. ISBN 978-90-04-21758-4.

- Zhang Guang-da (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume III: The crossroads of civilizations: AD 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 283. ISBN 978-8120815407.

- H. W. Bailey (1985-02-07). Indo-Scythian Studies: Being Khotanese Texts. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-521-11873-6.

- Callieri, Pierfrancesco (2016). "SAKAS: IN AFGHANISTAN". Encyclopædia Iranica.

The ethnonym Saka appears in ancient Iranian and Indian sources as the name of the large family of Iranian nomads called Scythians by the Classical Western sources and Sai by the Chinese (Gk. Sacae; OPers. Sakā).

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine; Bashilov, Vladimir A.; Yablonsky, Leonid T. (1995). Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age. Zinat Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-1-885979-00-1.

- Ivantchik, Askold (April 25, 2018). "SCYTHIANS". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- K. E. Eduljee. "Histories by Herodotus, Book 4 Melpomene [4.6]". Zoroastrian Heritage. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Parpola, Simo (1970). Neo-Assyrian Toponyms. Kevaeler: Butzon & Bercker. p. 178.

- "Iškuzaya [SCYTHIAN] (EN)". oracc.museum.upenn.edu.

- "Asguzayu [SCYTHIAN] (EN)". oracc.museum.upenn.edu.

- Cook 1985, p. 252-255.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2003). "HAUMAVARGĀ". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Dandamayev 1994, p. 44-46.

- Olbrycht 2000.

- Olbrycht 2021: "Apparently the Dahai represented an entity not identical with the other better known groups of the Sakai, i.e. the Sakai (Sakā) tigrakhaudā (Massagetai, roaming in Turkmenistan), and Sakai (Sakā) Haumavargā (in Transoxania and beyond the Syr Daryā)."

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2003). "HAUMAVARGĀ". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Dandamaev, Muhammad A.; Lukonin, Vladimir G. (1989). The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-521-61191-6.

- Francfort 1988, p. 173.

- Bailey 1983, p. 1230.

- Briant, Pierre (29 July 2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

This is Kingdom which I hold, from the Scythians [Saka] who are beyond Sogdiana, thence unto Ethiopia [Cush]; from Sind, thence unto Sardis.

- Cook 1985, p. 254-255.

- Young 1988, p. 89.

- Francfort 1988, p. 177.

- Bivar, A. D. H. (1983). "The History of Eastern Iran". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3.1. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 181-231. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- Schmitt 2018.

- Harmatta 1999.

- Abetekov, A.; Yusupov, H. (1994). "Ancient Iranian Nomads in Western Central Asia". In Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Harmatta, János; Puri, Baij Nath; Etemadi, G. F.; Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Paris, France: UNESCO. pp. 24–34. ISBN 978-9-231-02846-5.

- Zadneprovskiy, Y. A. (1994). "The Nomads of Northern Central Asia After the Invansion of Alexander". In Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Harmatta, János; Puri, Baij Nath; Etemadi, G. F.; Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Paris, France: UNESCO. pp. 448–463. ISBN 978-9-231-02846-5.

The middle of the third century b.c. saw the rise to power of a group of tribes consisting of the Parni (Aparni) and the Dahae, descendants of the Massagetae of the Aral Sea region.

- L. T. Yablonsky (2010-06-15). "The Archaeology of Eurasian Nomads". In Donald L. Hardesty (ed.). ARCHAEOLOGY – Volume I. EOLSS. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-84826-002-3.

- Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan; Hanagan, Michael P.; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise (16 March 2015). Global Connections: Volume 1, To 1500: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-316-29777-3.

- Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- Fauve, Jeroen (2021). The European Handbook of Central Asian Studies. p. 403. ISBN 978-3-8382-1518-1.

- Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan; Hanagan, Michael P.; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise (16 March 2015). Global Connections: Volume 1, To 1500: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-316-29777-3.

- Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- Fauve, Jeroen (2021). The European Handbook of Central Asian Studies. p. 403. ISBN 978-3-8382-1518-1.

- Francfort 1988, p. 168.

- Francfort 1988, p. 184.

- Olbrycht 2021.

- Yu 2010: "The Daxia 大夏 people in the valley of the Amu Darya came from the valleys of the rivers Ili and Chu. From the Geography of Strabo one can infer that the four tribes of the Asii and others came from these valleys (the so-called “land of the Sai 塞” in the Hanshu 漢書, ch. 96A). "

- Unterländer et al. 2017 "Genomic inference reveals that Scythians in the east and the west of the steppe zone can best be described as a mixture of Yamnaya-related ancestry and an East Asian component. Demographic modelling suggests independent origins for eastern and western groups with ongoing gene-flow between them, plausibly explaining the striking uniformity of their material culture. We also find evidence that significant gene-flow from east to west Eurasia must have occurred early during the Iron Age." and "The blend of EHG [European hunter-gatherer] and Caucasian elements in carriers of the Yamnaya culture was formed on the European steppe and exported into Central Asia and Siberia"

We therefore considered an alternative model in which we treat them as a mix of Yamnaya and the Han (Supplementary Table 25). This model fits all of the Iron Age Scythian groups, consistent with these groups having ancestry related to East Asians not found in the other populations. Alternatively, the Iron Age Scythian groups can also be modelled as a mix of Yamnaya and the north Siberian Nganasan (Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Table 26). - Unterländer et al. 2017 "The origin of the widespread Scythian culture has long been debated in Eurasian archaeology. The northern Black Sea steppe was originally considered the homeland and centre of the Scythians until Terenozhkin formulated the hypothesis of a Central Asian origin. On the other hand, evidence supporting an east Eurasian origin includes the kurgan Arzhan 1 in Tuva, which is considered the earliest Scythian kurgan. Dating of additional burial sites situated in east and west Eurasia confirmed eastern kurgans as older than their western counterparts. Additionally, elements of the characteristic ‘Animal Style' dated to the tenth century BCE were found in the region of the Yenisei river and modern-day China, supporting the early presence of Scythian culture in the East."

- de Laet & Herrmann 1996, p. 443 "The rich kurgan burials in Pazyryk, Siberia probably were those of Saka chieftains"

- Kuzmina 2008, p. 94 "Analysis of the clothing, which has analogies in the complex of Saka clothes, particularly in Pazyryk, led Wang Binghua (1987, 42) to the conclusion that they are related to the Saka Culture."

- Kuzmina 2007, p. 103 "The dress of Iranian-speaking Saka and Scythians is easily reconstructed on the basis of... numerous archaeological discoveries from the Ukraine to the Altai, particularly at Issyk in Kazakhstan... at Pazyryk... and Ak-Alakha"

- Lebedynsky 2007, p. 125.

- Harmatta 1996, p. 488: "Their royal tribes and kings (shan-yii) bore Iranian names and all the Hsiung-nu words noted by the Chinese can be explained from an Iranian language of Saka type. It is therefore clear that the majority of Hsiung-nu tribes spoke an Eastern Iranian language."

- William H. McNeill. "The Steppe – Scythian successes". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 2013-07-15. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

"The Steppe – Military and political developments among the steppe peoples to 100 bc". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2019-09-23. - J. P. mallory. "Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Penn Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-09.

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 553.

- Harmatta 1996.

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 560-590.

- Batty 2007, p. 202-203.

- Sulimirski 1985.

- Olbrycht 2021, p. 17-18.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2000). "ZARINAIA". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2014). The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton, United States: Princeton University Press. pp. 379–381. ISBN 978-0-691-14720-8.

- Francfort 1988, p. 171.

- Dandamayev 1994, pp. 35–64.

- Gera, Deborah Levine (2018). Warrior Women: The Anonymous Tractatus De Mulieribus. Leiden, Netherlands; New York City, United States: Brill. p. 199-200. ISBN 978-9-004-32988-1.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2014). The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton, United States: Princeton University Press. p. 382-383. ISBN 978-0-691-17027-5.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (2013). The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-136-01694-3.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (1989). "AMORGES". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- Dandamayev 1994.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1989). "DARIUS iii. Darius I the Great". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- Cunliffe, Barry (24 September 2015). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-19-968917-0.

- Dandamayev 1994, pp. 44–46

- Vogelsang 1992, p. 131.

- De Jong, Albert (1997). Traditions of the Magi: Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature. Leiden, Netherlands; New York City, United States: BRILL. p. 297. ISBN 978-9-004-10844-8.

- Vogelsang 1992, p. 160.

- Francfort 1988, p. 185: Besides trade and exchange within the borders of the Achaemenid empire, it seems that the part of Central Asua under Achaemenid rule was in contact wit the Saka tribes who were in touch with China (see the finds of kurgans II and V of Pazyryk and of Xinyuan and Alagou in Xinjiang).

- Baumer 2012, p. 290

- Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. p. 58. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- Torday, Laszlo. (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press, pp. 80–81, ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC – A.D. 220, 377–462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 377–388, 391, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Chang, Chun-shu. (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 BC – AD 157. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 5–8 ISBN 978-0-472-11534-1.

- Di Cosmo 2002, pp. 174–189

- Di Cosmo 2004, pp. 196–198

- Di Cosmo 2002, pp. 241–242

- Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp. 13–14, 21–22.

- Benjamin, Craig. "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia".

- Bernard, P. (1994). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia". In Harmatta, János. History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 96–126. ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- Baumer 2012, p. 296

- Bailey 1983.

- Ulrich Theobald. (26 November 2011). "Chinese History – Sai 塞 The Saka People or Soghdians." ChinaKnowledge.de. Accessed 2 September 2016.

- Lebedynsky 2006, p. 73.

- Mallory & Mair 2008, pp. 329–330.

- Lebedynsky 2006, p. 84.

- Attwood, Jayarava (2012). "Possible Iranian Origins for the Śākyas and Aspects of Buddhism". Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies. 3.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-1-4008-6632-8.

- Abdullaev, Kazim (2007). "Nomad Migration in Central Asia (in After Alexander: Central Asia before Islam)". Proceedings of the British Academy. 133: 87–98.

- Greek Art in Central Asia, Afghan – Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Also a Saka according to this source

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Ancient peoples and places. Vol. 73. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114. ISBN 9789080057272.

The evidence of both the ancient authors and the archaeological remains point to a massive migration of Sacian (Sakas) / Massagetan tribes from the Syr Daria Delta (Central Asia) by the middle of the second century B.C. Some of the Syr Darian tribes; they also invaded North India.

- Bivar, A. D. H. "KUSHAN DYNASTY i. Dynastic History". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982). India & Russia: linguistic & cultural affinity. Roma. p. 95.

- Mitchiner, Michael (1978). The ancient & classical world, 600 B.C.-A.D. 650. Hawkins Publications ; distributed by B. A. Seaby. p. 634. ISBN 978-0-904173-16-1.

- Loewe, Michael. (1986). "The Former Han Dynasty," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 103–222. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 197-198. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377-462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 410-411. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Windfuhr, Gernot (2013). Iranian Languages. Routledge. p. 377. ISBN 978-1-135-79704-1.

- Emmerick, R. E. (14 April 1983). "Chapter 7: Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs". In Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正). (1992). History of the Turks (突厥史). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, p. 596-598. ISBN 978-7-5004-0432-3; OCLC 28622013

- Beckwith, Christopher. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp 36, 146. ISBN 0-691-05494-0.

- Wechsler, Howard J.; Twitchett, Dennis C. (1979). Denis C. Twitchett; John K. Fairbank, eds. The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–227. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Hansen, Valerie (2005). "The Tribute Trade with Khotan in Light of Materials Found at the Dunhuang Library Cave" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 19: 37–46.

- Ulrich Theobald. (16 October 2011). "City-states Along the Silk Road." ChinaKnowledge.de. Accessed 2 September 2016.

- Xavier Tremblay, "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th Century", in The Spread of Buddhism, eds Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacker, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2007, p. 77.

- Ahmad Hasan Dani; B. A. Litvinsky; Unesco (1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. pp. 283–. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- Lurje, Pavel (2009). "YARKAND". Encyclopædia Iranica.

The territory of Yārkand is for the first time mentioned in the Hanshu (1st century BCE), under the name Shache (Old Chinese, approximately, *s³a(j)-ka), which is probably related to the name of the Iranian Saka tribes.

- Whitfield 2004, p. 47.

- Wechsler, Howard J.; Twitchett, Dennis C. (1979). Denis C. Twitchett; John K. Fairbank, eds. The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–228. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Scott Cameron Levi; Ron Sela (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- Akiner (28 October 2013). Cultural Change & Continuity In. Routledge. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0.

- "Strabo, Geography, 11.8.1". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2012-09-13.

- Kuz'mina, Elena E. (2007). The Origin of the Indo Iranians. Edited by J.P. Mallory. Leiden, Boston: Brill, pp 381-382. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

- Hansen, Valerie (2005). "The Tribute Trade with Khotan in Light of Materials Found at the Dunhuang Library Cave" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 19: 37–46. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- Sarah Iles Johnston, Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Harvard University Press, 2004. pg 197

- Edward A Allworth,Central Asia: A Historical Overview,Duke University Press, 1994. pp 86.

- Litvinsky, Boris Abramovich; Vorobyova-Desyatovskaya, M.I (1999). "Religions and religious movements". History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 421–448. ISBN 8120815408.

- Harmatta 1996, pp. 420–421.

- Kuz'mina, E.E. (2007). The Origins of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL.

- Peng, M.S.; Song, J.J.; Zhang, Y.P. (29 November 2017). "Mitochondrial genomes uncover the maternal history of the Pamir populations". European Journal of Human Genetics. 26 (1): 124–136. doi:10.1038/s41431-017-0028-8. PMC 5839027. PMID 29187735.

- Frye, R.N. (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. p. 192. ISBN 9783406093975.

[T]hese western Saka he distinguishes from eastern Saka who moved south through the Kashgar-Tashkurgan-Gilgit-Swat route to the plains of the sub-continent of India. This would account for the existence of the ancient Khotanese-Saka speakers, documents of whom have been found in western Sinkiang, and the modern Wakhi language of Wakhan in Afghanistan, another modern branch of descendants of Saka speakers parallel to the Ossetes in the west.

- Bailey, H.W. (1982). The culture of the Sakas in ancient Iranian Khotan. Caravan Books. pp. 7–10.

It is noteworthy that the Wakhi language of Wakhan has features, phonetics, and vocabulary the nearest of Iranian dialects to Khotan Saka.

- Windfuhr, G. (2013). Iranian Languages. Routeledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-135-79704-1.

- Carpelan, C.; Parpola, A.; Koskikallio, P. (2001). "Early Contacts Between Uralic and Indo-European: Linguistic and Archaeological Considerations: Papers Presented at an International Symposium Held at the Tvärminne Research Station of the University of Helsinki, 8–10 January, 1999". Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. 242: 136.

...descendants of these languages survive now only in the Ossete language of the Caucasus and the Wakhi language of the Pamirs, the latter related to the Saka once spoken in Khotan.

- Novak, L. (2014). "Question of (Re)classification of Eastern Iranian Languages". Linguistica Brunensia. 62 (1): 77–87.

- Clisson, I.; et al. (2002). "Genetic analysis of human remains from a double inhumation in a frozen kurgan in Kazakhstan (Berel site, early 3rd century BC)". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 116 (5): 304–308. doi:10.1007/s00414-002-0295-x. PMID 12376844. S2CID 27711154.

- Unterländer et al. 2017.

- Ricaut F.; et al. (2004). "Genetic Analysis of a Scytho-Siberian Skeleton and Its Implications for Ancient Central Asian Migrations". Human Biology. 76 (1): 109–125. doi:10.1353/hub.2004.0025. PMID 15222683. S2CID 35948291.

- Ricaut, F.; et al. (2004). "Genetic Analysis and Ethnic Affinities From Two Scytho-Siberian Skeletons". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 123 (4): 351–360. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10323. PMID 15022363.

- González-Ruiz, Mercedes; Santos, Cristina; Jordana, Xavier; Simón, Marc; Lalueza-Fox, Carles; Gigli, Elena; Aluja, Maria Pilar; Malgosa, Assumpció (2012). "Tracing the Origin of the East-West Population Admixture in the Altai Region (Central Asia)". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e48904. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...748904G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048904. PMC 3494716. PMID 23152818.

- Keyser, C; Bouakaze, C; Crubézy, E; et al. (September 2009). "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people". Human Genetics. 126 (3): 395–410. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0683-0. PMID 19449030. S2CID 21347353.

- Damgaard, Peter de Barros (May 2018). "137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes". Nature. 557 (7705): 369–374. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. "Principal component analyses and D-statistics suggest that the Xiongnu individuals belong to two distinct groups, one being of East Asian origin and the other presenting considerable admixture levels with West Eurasian sources... Principal Component Analyses and D-statistics suggest that the Xiongnu individuals belong to two distinct groups, one being of East Asian origin and the other presenting considerable admixture levels with West Eurasian sources... We find that Central Sakas are accepted as a source for these ‘western-admixed’ Xiongnu in a single-wave model. In line with this finding, no East Asian gene flow is detected compared to Central Sakas as these form a clade with respect to the East Asian Xiongnu in a D-statistic, and furthermore, cluster closely together in the PCA (Figure 2)... Overall, our data show that the Xiongnu confederation was genetically heterogeneous, and that the Huns emerged following minor male-driven East Asian gene flow into the preceding Sakas that they invaded... As such our results support the contention that the disappearance of the Inner Asian Scythians and Sakas around two thousand years ago was a cultural transition that coincided with the westward migration of the Xiongnu. This Xiongnu invasion also led to the displacement of isolated remnant groups related to Late Bronze Age pastoralists that had remained on the southeastern side of the Tian Shan mountains."

- Сергей Иванович Руденко (Sergei I. Rudenko) (1970). Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen. University of California Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-520-01395-7. Archived from the original on 2017-03-27. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- Day 2001, pp. 55–57

- Pliny. Naturalis Historia. 6. 88

- Dr. Aaron Ralby (2013). "Scythians, c. 700 BCE—600 CE: Punching a Cloud". Atlas of Military History. Parragon. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-1-4723-0963-1.

- Сергей Иванович Руденко (Sergei I. Rudenko) (1970). Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01395-7.

- "Chariot". Hermitage Museum. Archived from the original on July 6, 2001.

- "850 gold artefacts belonging to the Scythian-Saka era found in Kazakhstan". The Archaeology News Network. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- Mallory and Mair, The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, 2000)

- "Les Saces", Iaroslav Lebedynsky, p.73 ISBN 2-87772-337-2

- Crowns similar to the Scythian ones discovered in Tillia Tepe "appear later, during the 5th and 6th century at the eastern edge of the Asia continent, in the tumulus tombs of the Kingdom of Silla, in South-East Korea. "Afganistan, les trésors retrouvés", 2006, p282, ISBN 978-2-7118-5218-5

- "金冠塚古墳 – Sgkohun.world.coocan.jp". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-12-14.

- Gropp, G. "Clothing v. In Pre-Islamic Eastern Iran". iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- Di Cosmo 1999, 13.5. Statuette of warrior (a), and bronze cauldron (b), Saka....

- The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago Photographic Archives. Persepolis – Apadana, E Stairway, Tribute Procession, the Saka Tigraxauda Delegation. Archived 2012-10-12 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2012-6-27

Bibliography

- Akiner (28 October 2013). Cultural Change & Continuity in Central Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0.

- Bailey, H. W. 1958. "Languages of the Saka." Handbuch der Orientalistik, I. Abt., 4. Bd., I. Absch., Leiden-Köln. 1958.

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press. 1979. 1st Paperback edition 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-14250-2

- Bailey, H. W. (1983). "Khotanese Saka Literature". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3.2. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1230–1243. ISBN 978-0-521-24693-4.

- Batty, Roger (2007). Rome and the Nomads: The Pontic-Danubian Realm in Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-14936-1.

- Baumer, Christoph (2012). The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-060-5.

- Beckwith, Christopher. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05494-0.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Bernard, P. (1994). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia". In Harmatta, János. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 96–126. ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

- Chang, Chun-shu. (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-11534-1.

- Cook, J. M. (1985). "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire". In Gershevitch, Ilya (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 200–291. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2.

- Dandamayev, M. A. (1994). "Media and Achaemenid Iran". In Harmatta, János (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250. UNESCO. pp. 35–59. ISBN 9231028464. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Damgaard, P. B.; et al. (May 9, 2018). "137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes". Nature. Nature Research. 557 (7705): 369–373. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. PMID 29743675. S2CID 13670282. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- David, Bruno; McNiven, Ian J. (2018). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-060735-7.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine. 2002. Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines. Warner Books, New York. 1st Trade printing, 2003. ISBN 0-446-67983-6 (pbk).

- Day, John V. (2001). Indo-European origins: the anthropological evidence. Institute for the Study of Man. ISBN 0-941694-75-5. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (1999). "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China". The Cambridge History of Ancient China. pp. 885–966. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.015. ISBN 9781139053709.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77064-4.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (2004). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54382-7.

- Diakonoff, I. M. (1985). "Media". In Gershevitch, Ilya (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 36-148. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2.

- Bulletin of the Asia Institute: The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia. Studies From the Former Soviet Union. New Series. Edited by B. A. Litvinskii and Carol Altman Bromberg. Translation directed by Mary Fleming Zirin. Vol. 8, (1994), pp. 37–46.

- Emmerick, R. E. (2003) "Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1 (reprint edition) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 265–266.

- Francfort, Henri-Paul (1988). "Central Asia and Eastern Iran". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L.; Lewis, D. M.; Ostwald, M. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 4. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–193. ISBN 978-0-521-22804-6.

- Fraser, Antonia. (1989) The Warrior Queens Knopf.

- Harmatta, János (1994). "Conclusion". In Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Harmatta, János; Puri, Baij Nath; Etemadi, G. F.; Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Paris, France: UNESCO. pp. 24–34. ISBN 978-9-231-02846-5.

- Harmatta, János (1996). "10.4.1. The Scythians". In Hermann, Joachim; de Laet, Sigfried (eds.). History of Humanity. Vol. 3. UNESCO. ISBN 978-9-231-02812-0.

- Harmatta, János (1999). "Alexander the Great in Central Asia". Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 39: 129–136. doi:10.1556/aant.39.1999.1-4.11. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. John E. Hill. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Kuzmina, Elena Kuzmina (2007). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004160545.

- Kuzmina, Elena Kuzmina (2008). The Prehistory of the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4041-2.

- de Laet, Sigfried J.; Herrmann, Joachim (1996). History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. UNESCO. ISBN 923102812X.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav (2006). Les Saces (in French). Editions Errance. ISBN 2877723372.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav (2007). Les Nomades (in French). Editions Errance. ISBN 978-2877722544.

- Loewe, Michael. (1986). "The Former Han Dynasty," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 103–222. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Mallory, J.P.; Mair, Victor H. (2008). The Tarim mummies : ancient China and the mystery of the earliest peoples from the West (1st pbk. ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28372-1.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231139241.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2021). Early Arsakid Parthia (ca. 250-165 B.C.): At the Crossroads of Iranian, Hellenistic, and Central Asian History. Leiden, Netherlands ; Boston, United States: Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-46076-8.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2000). "Remarks on the Presence of Iranian Peoples in Europe and Their Asiatic Relations". Collectanea Celto-Asiatica Cracoviensia. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka. pp. 101–104. ISBN 978-8-371-88337-8.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1970. "The Wu-sun and Sakas and the Yüeh-chih Migration." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 33 (1970), pp. 154–160.

- Puri, B. N. 1994. "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 191–207.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2018). "MASSAGETAE". Encyclopædia Iranica.