Andrew the Apostle

Andrew the Apostle (Koinē Greek: Ἀνδρέᾱς, romanized: Andréās [anˈdre.aːs̠]; Latin: Andrēās [än̪ˈd̪reː.äːs]; Aramaic: אַנדּרֵאוָס, Classical Syriac: ܐܰܢܕ݁ܪܶܐܘܳܣ, romanized: ʾAnd’reʾwās[4]), also called Saint Andrew, was an apostle of Jesus according to the New Testament. He is the brother of Simon Peter[5] and is a son of Jonah. He is referred to in the Orthodox tradition as the First-Called (Πρωτόκλητος, Prōtoklētos).

Andrew the Apostle | |

|---|---|

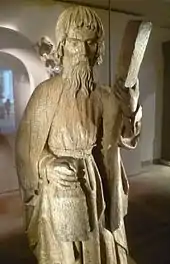

Saint Andrew (c. 1611) by Peter Paul Rubens | |

| Apostle and Martyr | |

| Born | c. AD 5 Bethsaida, Galilee, Roman Empire |

| Died | AD 60/70[1] Patras, Achaea, Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations which venerate saints |

| Major shrine | St Andrew's Cathedral, Patras, Greece; St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland; the Church of St Andrew and St Albert, Warsaw, Poland; Duomo Cathedral in Amalfi and Sarzana Cathedral in Sarzana, Italy. |

| Feast | 30 November |

| Attributes | Old man with long white hair and beard, holding the Gospel Book or scroll, sometimes leaning on a saltire, fishing net |

| Patronage | Scotland, Barbados, Georgia, Ukraine, Russia, Greece, Cyprus, Romania, Patras, Burgundy, San Andrés (Tenerife), Diocese of Parañaque, Candaba, Pampanga, Masinloc, Telhado, Sarzana,[2] Pienza,[3] Amalfi, Luqa (Malta) and Prussia; Diocese of Victoria; fishermen, fishmongers and rope-makers, textile workers, singers, miners, pregnant women, butchers, farm workers, protection against sore throats, protection against convulsions, protection against fever, protection against whooping cough, Russian Navy |

According to Orthodox tradition, the apostolic successor to Andrew is the Patriarch of Constantinople.[6]

Life

_-_The_Calling_of_Saints_Peter_and_Andrew_-_RCIN_402824_-_Hampton_Court_Palace.jpg.webp)

The name "Andrew" (meaning manly, brave, from Greek: ἀνδρεία, translit. andreía, lit. "manhood, valour"), like other Greek names, appears to have been common among the Jews and other Hellenized people of Judea. No Hebrew or Aramaic name is recorded for him.

Andrew the Apostle was born between 5 and 10 AD[7] in Bethsaida, in Galilee.[8] The New Testament states that Andrew was the brother of Simon Peter,[9] and likewise a son of Jonah. "The first striking characteristic of Andrew is his name: it is not Hebrew, as might have been expected, but Greek, indicative of a certain cultural openness in his family that cannot be ignored. We are in Galilee, where the Greek language and culture are quite present."[10]

Both he and his brother Peter were fishermen by trade, hence the tradition that Jesus called them to be his disciples by saying that he will make them "fishers of men" (Greek: ἁλιεῖς ἀνθρώπων, translit. halieîs anthrṓpōn).[11] At the beginning of Jesus' public life, they were said to have occupied the same house at Capernaum.

In the Gospel of Matthew[12] and in the Gospel of Mark[13] Simon Peter and Andrew were both called together to become disciples of Jesus and "fishers of men". These narratives record that Jesus was walking along the shore of the Sea of Galilee, observed Simon and Andrew fishing, and called them to discipleship.

In the parallel incident in the Gospel of Luke[14] Andrew is not named, nor is reference made to Simon having a brother. In this narrative, Jesus initially used a boat, solely described as being Simon's, as a platform for preaching to the multitudes on the shore and then as a means to achieving a huge trawl of fish on a night which had hitherto proved fruitless. The narrative indicates that Simon was not the only fisherman in the boat (they signalled to their partners in the other boat …[15] but it is not until the next chapter[16] that Andrew is named as Simon's brother. However, it is generally understood that Andrew was fishing with Simon on the night in question. Matthew Poole, in his Annotations on the Holy Bible, stressed that 'Luke denies not that Andrew was there'.[17]

In contrast, the Gospel of John[18] states that Andrew was a disciple of John the Baptist, whose testimony first led him, and another unnamed disciple of John the Baptist, to follow Jesus. Andrew at once recognized Jesus as the Messiah, and hastened to introduce him to his brother.[19] The Byzantine Church honours him with the name Protokletos, which means "the first called".[10] Thenceforth, the two brothers were disciples of Christ. On a subsequent occasion, prior to the final call to the apostolate, they were called to a closer companionship, and then they left all things to follow Jesus.

Subsequently, in the gospels, Andrew is referred to as being present on some important occasions as one of the disciples more closely attached to Jesus.[lower-alpha 1] Andrew told Jesus about the boy with the loaves and fishes,[20] and when Philip wanted to tell Jesus about certain Greeks seeking Him, he told Andrew first.[21] Andrew was present at the Last Supper.[22] Andrew was one of the four disciples who came to Jesus on the Mount of Olives to ask about the signs of Jesus' return at the "end of the age".[23]

Eusebius in his Church History 3.1 quoted Origen as saying that Andrew preached in Scythia. The Chronicle of Nestor adds that he preached along the Black Sea and the Dnieper river as far as Kiev, and from there he travelled to Novgorod. Hence, he became a patron saint of Ukraine, Romania and Russia. According to Hippolytus of Rome, Andrew preached in Thrace, and his presence in Byzantium is mentioned in the apocryphal Acts of Andrew. According to tradition, he founded the see of Byzantium (later Constantinople) in AD 38, installing Stachys as bishop. This diocese became the seat of the Patriarchate of Constantinople under Anatolius, in 451. Andrew, along with Stachys, is recognized as the patron saint of the Patriarchate.[24] Basil of Seleucia also knew of Apostle Andrew's missions in Thrace, Scythia and Achaea.[25]

Andrew is said to have been martyred by crucifixion at the city of Patras (Patræ) in Achaea, in AD 60.[22] Early texts, such as the Acts of Andrew known to Gregory of Tours,[26] describe Andrew as bound, not nailed, to a Latin cross of the kind on which Jesus is said to have been crucified; yet a tradition developed that Andrew had been crucified on a cross of the form called crux decussata (X-shaped cross, or "saltire"), now commonly known as a "Saint Andrew's Cross" — supposedly at his own request, as he deemed himself unworthy to be crucified on the same type of cross as Jesus had been.[lower-alpha 2] The iconography of the martyrdom of Andrew — showing him bound to an X-shaped cross — does not appear to have been standardized until the later Middle Ages.[27][lower-alpha 3]

The Acts of Andrew

The apocryphal Acts of Andrew, mentioned by Eusebius, Epiphanius and others, is among a disparate group of Acts of the Apostles that were traditionally attributed to Leucius Charinus. "These Acts (...) belong to the third century: ca. A.D. 260," in the opinion of M. R. James, who edited them in 1924. The Acts, as well as a Gospel of St Andrew, appear among rejected books in the Decretum Gelasianum connected with the name of Pope Gelasius I. The Acts of Andrew was edited and published by Constantin von Tischendorf in the Acta Apostolorum apocrypha (Leipzig, 1821), putting it for the first time into the hands of a critical professional readership. Another version of the Andrew legend is found in the Passio Andreae, published by Max Bonnet (Supplementum II Codicis apocryphi, Paris, 1895).

Relics

Relics alleged to be those of the Apostle Andrew are kept at the Basilica of Saint Andrew in Patras, Greece; in Amalfi Cathedral (the Duomo di Sant'Andrea), Amalfi and in Sarzana Cathedral[2] in Sarzana, Italy; St Mary's Roman Catholic Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland;[19] and the Church of St Andrew and St Albert, Warsaw, Poland. There are also numerous smaller reliquaries throughout the world.

Andrew's remains were preserved at Patras. According to one legend, Regulus (Rule), a monk at Patras, was advised in a dream to hide some of the bones. Shortly thereafter, most of the relics were transferred from Patras to Constantinople by order of the Roman emperor Constantius II around 357 and deposited in the Church of the Holy Apostles.[22]

Regulus was said to have had a second dream in which an angel advised him to take the hidden relics "to the ends of the earth" for protection. Wherever he was shipwrecked, he was to build a shrine for them. St. Rule set sail, taking with him a kneecap, an upper arm bone, three fingers and a tooth. He sailed west, towards the edge of the known world, and was shipwrecked on the coast of Fife, Scotland. However, the relics were probably brought to Britain in 597 as part of the Augustine Mission, and then in 732 to Fife, by Bishop Acca of Hexham, a well-known collector of religious relics.[19]

The skull of Saint Andrew, which had been taken to Constantinople, was returned to Patras by Emperor Basil I, who ruled from 867 to 886.[28]

In 1208, following the sack of Constantinople, those relics of Saint Andrew and Saint Peter which remained in the imperial city were taken to Amalfi, Italy,[29] by Cardinal Peter of Capua, a native of Amalfi. A cathedral (Duomo), was built, dedicated to Saint Andrew (as is the town itself), to house a tomb in its crypt where it is maintained that most of the relics of the apostle, including an occipital bone, remain.

Thomas Palaeologus was the youngest surviving son of Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos. Thomas ruled the province of Morea, the medieval name for the Peloponnese. In 1461, when the Ottomans crossed the Strait of Corinth, Palaeologus fled Patras for exile in Italy, bringing with him what was purported to be the skull of Saint Andrew. He gave the head to Pope Pius II, who had it enshrined in one of the four central piers of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican and then in Pienza,[3] Italy.

In September 1964, Pope Paul VI, as a gesture of goodwill toward the Greek Orthodox Church, ordered that all of the relics of Saint Andrew that were in Vatican City be sent back to Patras. Cardinal Augustin Bea along with many other cardinals presented the skull to Bishop Constantine of Patras on 24 September 1964.[30] The cross of Saint Andrew was taken from Greece during the Crusades by the Duke of Burgundy.[31][32] It was kept in the church of St. Victor in Marseilles[33] until it returned to Patras on 19 January 1980. The cross of the apostle was presented to the Bishop of Patras Nicodemus by a Catholic delegation led by Cardinal Roger Etchegaray. All the relics, which consist of the small finger, the skull (part of the top of the cranium of Saint Andrew), and the cross on which he was martyred, have been kept in the Church of St. Andrew at Patras in a special shrine and are revered in a special ceremony every 30 November, his feast day.

In 2006, the Catholic Church, again through Cardinal Etchegaray, gave the Greek Orthodox Church another relic of Saint Andrew.[34]

Traditions and legends

Georgia

.JPG.webp)

The church tradition of Georgia regards Andrew as the first preacher of Christianity in the territory of Georgia and as the founder of the Georgian church. This tradition was apparently derived from the Byzantine sources, particularly Nicetas of Paphlagonia (died c. 890) who asserts that "Andrew preached to the Iberians, Sauromatians, Taurians, and Scythians and to every region and city, on the Black Sea, both north and south."[35] The version was adopted by the 10th–11th-century Georgian ecclesiastics and, refurbished with more details, was inserted in the Georgian Chronicles. The story of Andrew's mission in the Georgian lands endowed the Georgian church with apostolic origin and served as a defence argument to George the Hagiorite against the encroachments from the Antiochian church authorities on autocephaly of the Georgian church. Another Georgian monk, Ephraim the Minor, produced a thesis, reconciling Andrew's story with an earlier evidence of the 4th-century conversion of Georgians by Nino and explaining the necessity of the "second Christening" by Nino. The thesis was made canonical by the Georgian church council in 1103.[36][37] The Georgian Orthodox Church marks two feast days in honour of Saint Andrew, on 12 May and 13 December. The former date, dedicated to Andrew's arrival in Georgia, is a public holiday in Georgia.

Cyprus

Cypriot tradition holds that a ship which was transporting Andrew went off course and ran aground. Upon coming ashore, Andrew struck the rocks with his staff at which point a spring of healing waters gushed forth. Using it, the sight of the ship's captain, who had been blind in one eye, was restored. Thereafter, the site became a place of pilgrimage and a fortified monastery, the Apostolos Andreas Monastery, stood there in the 12th century, from which Isaac Comnenus negotiated his surrender to Richard the Lionheart. In the 15th century, a small chapel was built close to the shore. The main monastery of the current church dates to the 18th century.

Other pilgrimages are more recent. The story is told that in 1895, the son of a Maria Georgiou was kidnapped. Seventeen years later, Andrew appeared to her in a dream, telling her to pray for her son's return at the monastery. Living in Anatolia, she embarked on the crossing to Cyprus on a very crowded boat. As she was telling her story during the journey, one of the passengers, a young Dervish priest, became more and more interested. Asking if her son had any distinguishing marks, he stripped off his clothes to reveal the same marks and mother and son were thus reunited.[38]

Apostolos Andreas Monastery (Greek: Απόστολος Ανδρέας) is a monastery dedicated to Saint Andrew situated just south of Cape Apostolos Andreas, which is the north-easternmost point of the island of Cyprus, in Rizokarpaso in the Karpass Peninsula. The monastery is an important site to the Cypriot Orthodox Church. It was once known as 'the Lourdes of Cyprus', served not by an organized community of monks but by a changing group of volunteer priests and laymen. Both Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities consider the monastery a holy place. As such, it is visited by many people for votive prayers.

Malta

The first reference regards the small chapel at Luqa dedicated to Andrew dates to 1497. This chapel contained three altars, one of them dedicated to Andrew. The painting showing Mary with Saints Andrew and Paul was painted by the Maltese artist Filippo Dingli. At one time, many fishermen lived in the village of Luqa, and this may be the main reason for choosing Andrew as patron saint. The statue of Andrew was sculpted in wood by Giuseppe Scolaro in 1779. This statue underwent several restoration works including that of 1913 performed by the Maltese artist Abraham Gatt. The Martyrdom of Saint Andrew on the main altar of the church was painted by Mattia Preti in 1687.

Romania

The official stance of the Romanian Orthodox Church is that Andrew preached the Gospel in the province of Dobruja (Scythia Minor) to the Daco-Romans, whom he is said to have converted to Christianity. Such a tradition was however not widely acknowledged until the 20th century.

According to Hippolyte of Antioch, (died c. 250 C.E.) in his On Apostles, Origen in the third book of his Commentaries on the Genesis (254 C.E.), Eusebius of Caesarea in his Church History (340 C.E.), and other sources, such as Usaard's Martyrdom written between 845 and 865, and Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend (c. 1260), Andrew preached in Scythia, a possible reference to Scythia Minor, whose territory was integrated into Romania in the late 19th century.

According to some modern Romanian scholars, the idea of early Christianisation is unsustainable. They take the idea to be a part of an ideology of protochronism which purports that the Orthodox Church has been a companion and defender of the Romanian people for its entire history, which was then used for propaganda purposes during the communist era,[39] although this is disputed.

East Slavs

Tradition regarding the early Christian history of Ukraine holds that the apostle Andrew preached on the southern borders of modern-day Ukraine, along the Black Sea. Legend has it that he travelled up the Dnieper River and reached the future location of Kyiv, where he erected a cross on the site where the Saint Andrew's Church of Kyiv currently stands, and where he prophesied the foundation of a great Christian city.[40] Because of this connection to Kyiv, Andrew is considered to be the patron saint of the two East Slavic nations descended from the Kievan Rus: Ukraine and Russia, the latter country using the Saint Andrew's Cross on its naval ensign. The third East Slavic nation, Belarus, however, reveres Euphrosyne of Polotsk, a local saint, as its patron instead.

Scotland

Several legends state that the relics of Andrew were brought by divine guidance from Constantinople to the place where the modern Scottish town of St Andrews stands today (Gaelic, Cill Rìmhinn). The oldest surviving manuscripts are two: one is among the manuscripts collected by Jean-Baptiste Colbert and willed to Louis XIV of France, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; the other is the Harleian Mss in the British Library, London. They state that the relics of Andrew were brought by one Regulus to the Pictish king Óengus mac Fergusa (729–761). The only historical Regulus (Riagail or Rule) whose name is preserved in the tower of St Rule was an Irish monk expelled from Ireland with Columba; his dates, however, are c. 573 – 600. There are good reasons for supposing that the relics were originally in the collection of Acca, bishop of Hexham, who took them into Pictish country when he was driven from Hexham (c. 732), and founded a see, not, according to tradition, in Galloway, but on the site of St Andrews.

According to legendary accounts given in 16th-century historiography, Óengus II in AD 832 led an army of Picts and Scots into battle against the Angles, led by Æthelstan, near modern-day Athelstaneford, East Lothian. The legend states that he was heavily outnumbered and hence whilst engaged in prayer on the eve of battle, Óengus vowed that if granted victory he would appoint Andrew as the patron saint of Scotland. On the morning of battle white clouds forming an X shape in the sky were said to have appeared. Óengus and his combined force, emboldened by this apparent divine intervention, took to the field and despite being inferior in numbers were victorious. Having interpreted the cloud phenomenon as representing the crux decussata upon which Andrew was crucified, Óengus honoured his pre-battle pledge and duly appointed Andrew as the patron saint of Scotland. The white saltire set against a celestial blue background is said to have been adopted as the design of the flag of Scotland on the basis of this legend.[41] However, there is evidence that Andrew was venerated in Scotland before this.

Andrew's connection with Scotland may have been reinforced following the Synod of Whitby, when the Celtic Church felt that Columba had been "outranked" by Peter and that Peter's brother would make a higher-ranking patron. The 1320 Declaration of Arbroath cites Scotland's conversion to Christianity by Andrew, "the first to be an Apostle". Numerous parish churches in the Church of Scotland and congregations of other Christian churches in Scotland are named after Andrew. The national church of the Scottish people in Rome, Sant'Andrea degli Scozzesi is dedicated to Saint Andrew.

A local superstition uses the cross of Saint Andrew as a hex sign on the fireplaces in northern England and Scotland to prevent witches from flying down the chimney and entering the house to do mischief. By placing the Saint Andrew's cross on one of the fireplace posts or lintels, witches are prevented from entering through this opening. In this case, it is similar to the use of a witch ball, although the cross will actively prevent witches from entering, whereas the witch ball will passively delay or entice the witch, and perhaps entrap it.

Spain

A form of St. Andrew's cross called the Cross of Bourgogne was used as the flag of the Duchy of Burgundy, and after the Duchy was acquired by Spain, by the Spanish Crown, and later as a Spanish naval flag and finally as an army battle flag up until 1843. Today, it is still a part of various Spanish military insignia and forms part of the Coat of Arms of the king of Spain as it did with General Franco.

In Spain, Andrew is the patron of several locations: San Andrés (Santa Cruz de Tenerife), San Andrés y Sauces (La Palma), Navalmoral de la Mata (Cáceres), Éibar (Guipúzcoa), Baeza (Jaén), Pobladura de Pelayo García and Pobladura de Yuso (León), Berlangas de Roa (Burgos), Ligüerzana (Palencia), Castillo de Bayuela (Toledo), Almoradí (Alicante), Estella (Navarra), Sant Andreu de Palomar, (Barcelona), Pujalt (Catalonia), Adamuz (Córdoba) and San Andrés in Cameros (La Rioja).

Legacy

Andrew is the patron saint of several countries and cities including: Barbados, Romania, Russia, Scotland, Ukraine, Sarzana,[2] Pienza[3] and Amalfi in Italy, Esgueira in Portugal, Luqa in Malta, Parañaque in the Philippines and Patras in Greece. He was also the patron saint of Prussia and of the Order of the Golden Fleece. He is considered the founder and the first bishop of the Church of Byzantium and is consequently the patron saint of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Apostle Andrew is also the patron of the Russian Navy.

The flag of Scotland (and consequently the Union Flag and those of some of the former colonies of the British Empire) feature Saint Andrew's saltire cross. The saltire is also the flag of Tenerife, the former flag of Galicia and the Russian Navy Ensign. The Confederate flag also features a saltire commonly referred to as a St Andrew's cross, although its designer, William Porcher Miles, said he changed it from an upright cross to a saltire so that it would not be a religious symbol but merely a heraldic device. The Alabama flag also shows that device.

The feast of Andrew is observed on 30 November in both the Eastern and Western churches, and is the national day of Scotland. In the traditional liturgical books of the Catholic Church, the feast of Saint Andrew is the first feast day in the Proper of Saints.

Andrew the Apostle is remembered in the Church of England with a Festival on 30 November.[42]

In Islam

The Qur’anic account of the disciples of Jesus does not include their names, numbers, or any detailed accounts of their lives. Muslim exegesis, however, more or less agrees with the New Testament list and says that the disciples included Andrew.[43]

In the Gospel of Mary

According to the Gospel of Mary, a non-canonical text containing ideas paralleling those found in Gnosticism, Andrew along with the apostle Peter did not truly understand the teachings of Jesus. Rather, in its narrative, a woman named Mary (presumably Mary Magdelene) is superior to them with her knowledge.[44][45]

See also

- Order of Saint Andrew

- Patron saints of places

- Saltire – the X-shaped cross in heraldry and vexillology

- Santo André — an industrial town in Brazil

- St. Andrew's College, an all-boys independent school in Ontario, Canada, named after St. Andrew. On the driveway to the main building, there is a Saint Andrew statue

- St. Andrew's Cross (disambiguation)

- Saint Andrew's Day

- Russian Navy

- Universidad de San Andrés — Argentina, named after the saint

- University of St Andrews — named after the Royal Burgh of St Andrews, which was named after the saint

- St. Andrew's College

- Cross of Saint Peter

- Saint Andrew the Apostle, patron saint archive

- St. Andrew's School Parañaque

References

Notes

- Bible: Mark 13:3; Bible: John 6:8, Bible: 12:22; but in Acts of the Apostles there is only one mention of him. Bible: Acts 1:13

- The legends surrounding Andrew are discussed in Dvornik 1958

- According to Réau 1958, p. 79, St. Andrew's Cross appeared for the first time in the tenth century, but did not become an iconographic standard before the seventeenth. Calvert 1984 was unable to find a sculptural representation of Andrew on the saltire cross earlier than an architectural capital from Quercy, of the early twelfth century.

Citations

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "St. Andrew". Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 May. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Andrew. Accessed 1 December 2021.

- "Cattedrale di Sarzana".

- Williams & Maxwell 2018, p. 300.

- "Dukhrana – Andreas/Andrew/ܐܢܕܪܐܘܣ". Dukhrana.com. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "BBC – History – St Andrew". www.bbc.co.uk.

- Apostolic Succession of the Great Church of Christ, Ecumenical Patriarchate, archived from the original on 19 July 2014, retrieved 2 August 2014

- Turnbull, Michael T. R. B. (31 July 2009). "Saint Andrew". BBC- Religions. BBC. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Henderson, Emma (30 November 2015). "St Andrew's Day: 5 facts about St Andrew you need to know". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Butler, Alban. The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs and Other Principal Saints, Vol. III".

- "General Audience of 14 June 2006: Andrew, the "Protoclete" | BENEDICT XVI". www.vatican.va.

- Metzger & Coogan 1993, p. 27.

- Bible: Matt 4:18–22

- Bible: Mark 1:16–20

- Bible: Luke 5:1–11

- Bible: Luke 5:7

- Bible: Luke 6:14

- Matthew Poole's Commentary on Luke 5, accessed 19 February 2017

- Bible: John 1:35–42

- "National Shrine of St Andrew in Edinburgh Scotland". Stmaryscathedral.co.uk. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- Bible: John 6:8

- Bible John 12:20–22

- MacRory 1907.

- Bible: Mark 13:3

- "Οικουμενικό Πατριαρχείο".

- Ferguson 2013, p. 51.

- In Monumenta Germaniae Historica II, cols. 821–847, translated in M.R. James, The Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford) reprinted 1963:369.

- Calvert 1984, p. 545, note 12.

- Christodoulou, Alexandros. "St. Andrew, Christ’s First-Called Disciple", Pemptousia Archived 17 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- National Archives of Scotland (23 November 2011). "St. Andrew in the National Archives of Scotland". Nas.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- "Η ΤΙΜΙΑ ΚΑΡΑ ΤΟΥ ΑΠΟΣΤΟΛΟΥ ΑΝΔΡΕΟΥ ΤΟΥ ΠΡΩΤΟΚΛΗΤΟΥ". i-m-patron.gr.

- "La croix de Saint André". Vexil.prov.free.fr. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Denoël 2004.

- "Abbaye Saint-Victor de Marseille, monuments historiques en France (in French)". Monumentshistoriques.free.fr. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Relic of St. Andrew Given to Greek Orthodox Church. Zenit News Agency (via Zenit.org). Published: 27 February 2006.

- Peterson 1958, p. 20.

- Rapp 2003, p. 433.

- Djobadze 1976, pp. 82–83.

- "Apostolos Andreas Monastery, Karpaz, North Cyprus". Whatson-northcyprus.com. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Stan & Turcescu 2007, p. 48.

- Lytvynchuk, Janna. St. Andrew's Church, p. 7, Kyiv: Anateya, 2006, ISBN 966-8668-22-7

- Parker Lawson 1848, p. 169.

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Noegel & Wheeler 2002, p. 86.

- Karen King (2003). "Introduction". The Gospel of Mary Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle. Polebridge. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Maurice Casey (3 December 2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. A & C Black. p. 536. ISBN 9780567645173. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

Sources

- Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. 3rd edition. New York: Penguin Books, 1993. ISBN 0-14-051312-4

- Calvert, Judith (1984). "The Iconography of the St. Andrew Auckland Cross". The Art Bulletin. 66 (4): 543–555. doi:10.1080/00043079.1984.10788208. ISSN 0004-3079.

- Denoël, Charlotte (2004). Saint André: culte et iconographie en France, Ve-XVe siècles. École nationale des chartes. ISBN 978-2-900791-73-8.

- Dvornik, Francis (1958). The Idea of Apostolicity in Byzantium and the Legend of the Apostle Andrew. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-88402-004-2.

- Djobadze, Wachtang Z. (1976). "Materials for the Study of Georgian Monasteries in the Western Environs of Antioch on the Orontes". Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium. Louvain. 372, subsidia 48.: 82–83.

- Ferguson, Everett (2013). Encyclopedia of Early Christianity: Second Edition. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-61158-2.

- MacRory, Joseph (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D., eds. (1993). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

- Noegel, Scott B.; Wheeler, Brandon M. (2002). Historical Dictionary of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow. ISBN 978-0810843059.

- Parker Lawson, John (1848). History of the Abbey and Palace of Holyroodhouse. H. Courtoy.

- Peterson, Peter M. (1958). Andrew, brother of Simon Peter: His history and legends. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-26579-0.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2003). Studies in Medieval Georgian Historiography: Early Texts and Eurasian Contexts. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1318-9.

- Réau, Louis (1958). Iconographie de l'art chrétien [Iconography of Christian Art] (in French). Vol. III.1. Paris.

- Stan, Lavinia; Turcescu, Lucian (2007). Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-804217-4.

- Williams, Nicola; Maxwell, Virginia (2018). Florence & Tuscany. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-78701-193-9.

External links

- Andreas: The Legend of St. Andrew translated by Robert Kilburn Root, 1899, from Project Gutenberg

- National Shrine to Saint Andrew in Edinburgh Scotland

- Grimm's Saga No. 150 about Saint Andrew

- "Saint Andrew" at the Christian Iconography website

- "The Life of St. Andrew" from Caxton's translation of the Golden Legend