Scottish National Party

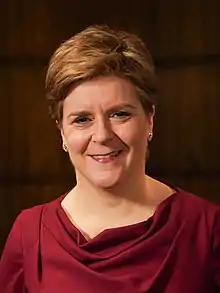

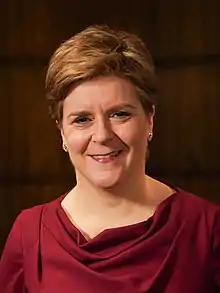

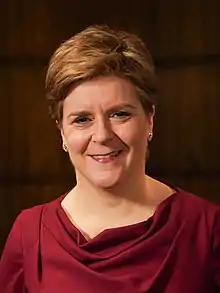

The Scottish National Party (SNP; Scots: Scots National Pairty, Scottish Gaelic: Pàrtaidh Nàiseanta na h-Alba [ˈpʰaːrˠʃtʲi ˈn̪ˠaːʃən̪ˠt̪ə nə ˈhal̪ˠapə]) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic political party in Scotland. The SNP supports and campaigns for Scottish independence from the United Kingdom and for membership of the European Union,[13][25][26] with a platform based on civic nationalism.[27][28] The SNP is the largest political party in Scotland, where it has the most seats in the Scottish Parliament and 45 out of the 59 Scottish seats in the House of Commons at Westminster, and it is the third-largest political party by membership in the United Kingdom, behind the Labour Party and the Conservative Party. The current Scottish National Party leader, Nicola Sturgeon, has served as First Minister of Scotland since 20 November 2014.

Scottish National Party Scots National Pairty Pàrtaidh Nàiseanta na h-Alba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | SNP |

| Leader | Nicola Sturgeon |

| Depute Leader | Keith Brown |

| House of Commons Leader | Ian Blackford |

| President | Michael Russell |

| Chief Executive | Peter Murrell |

| Founded | 7 April 1934 |

| Merger of |

|

| Headquarters | Gordon Lamb House 3 Jackson's Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ |

| Student wing | SNP Students |

| Youth wing | Young Scots for Independence |

| LGBT wing | Out for Independence |

| Membership (2021) | |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Centre-left[19][20] |

| European affiliation | European Free Alliance |

| Colours | Yellow Black |

| Anthem | "Scots Wha Hae"[21][22] |

| House of Commons (Scottish seats) | 44 / 59 |

| Scottish Parliament[23] | 64 / 129 |

| Local government in Scotland[24] | 453 / 1,227 |

| Website | |

| www | |

| |

Founded in 1934 with the amalgamation of the National Party of Scotland and the Scottish Party, the party has had continuous parliamentary representation in Westminster since Winnie Ewing won the 1967 Hamilton by-election.[29] With the establishment of the devolved Scottish Parliament in 1999, the SNP became the second-largest party, serving two terms as the opposition. The SNP gained power under Alex Salmond at the 2007 Scottish Parliament election, forming a minority government, before going on to win the 2011 Parliament election, after which it formed Holyrood's first majority government.[30] After Scotland voted against independence in the 2014 referendum, Salmond resigned and was succeeded by Sturgeon. The SNP was reduced back to being a minority government at the 2016 election. In the 2021 election, the SNP gained one seat and entered a power-sharing agreement with the Scottish Greens.

The SNP is the largest political party in Scotland in terms of both seats in the Westminster and Holyrood parliaments, and membership, reaching 125,691 members as of March 2021, 45 Members of Parliament (MPs), 64 Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) and over 450 local councillors.[31] The SNP is a member of the European Free Alliance (EFA). The party does not have any members of the House of Lords, as it has always maintained a position of objecting to an unelected upper house.[32][33]

History

Foundation and early breakthroughs (1934–1970)

The SNP was formed in 1934 through the merger of the National Party of Scotland and the Scottish Party, with the Duke of Montrose and Cunninghame Graham as its first, joint, presidents.[34] Sir Alexander MacEwen was its first chairman.[35]

The party was divided on its approach to the Second World War. Professor Douglas Young, who was SNP leader from 1942 to 1945, campaigned for the Scottish people to refuse conscription and his activities were popularly vilified as undermining the British war effort against the Axis powers. Young was imprisoned for refusing to be conscripted. However, others in the party were explicitly pro-Nazi. Hugh MacDiarmid, who stood as an SNP candidate in 1945, believed that the Nazis were "less dangerous than our own government" and wrote a poem about the London Blitz that included the line "I hardly care".[36][37][38] Arthur Donaldson, who went on to lead the party between 1961 and 1969, believed a Nazi invasion would benefit Scotland:[39]

"The government would leave the country and England's position would be absolutely hopeless, as poverty and famine would be their only reward for declaring war on Germany. Scotland, on the other hand, had great possibilities."

The party suffered its first split during this period with John MacCormick leaving the party in 1942, owing to his failure to change the party's policy from supporting all-out independence to Home Rule at that year's conference in Glasgow. McCormick went on to form the Scottish Covenant Association, a non-partisan political organisation campaigning for the establishment of a devolved Scottish Assembly.

However, wartime conditions also enabled the SNP's first parliamentary success at the Motherwell by-election in 1945, but Robert McIntyre MP lost the seat at the general election three months later. The 1950s were characterised by similarly low levels of support, and this made it difficult for the party to advance. Indeed, in most general elections they were unable to put up more than a handful of candidates.

The 1960s, however, offered more electoral successes, with candidates polling credibly at Glasgow Bridgeton in 1961, West Lothian in 1962 and Glasgow Pollok in 1967. Indeed, this foreshadowed Winnie Ewing's surprise victory in a by-election at the previously safe Labour seat of Hamilton. This brought the SNP to national prominence, leading to the establishment of the Kilbrandon Commission.

Becoming a notable force (1970s)

Despite this breakthrough, the 1970 general election was to prove a disappointment for the party as, despite an increase in vote share, Ewing failed to retain her seat in Hamilton. The party did receive some consolation with the capture of the Western Isles, making Donald Stewart the party's only MP. This was to be the case until the 1973 by-election at Glasgow Govan where a hitherto safe Labour seat was claimed by Margo MacDonald.

1974 was to prove something of an annus mirabilis for the party as it deployed its highly effective It's Scotland's oil campaign.[40] The SNP gained 6 seats at the February general election before hitting a high point in the October re-run, polling almost a third of all votes in Scotland and returning 11 MPs to Westminster. Furthermore, during that year's local elections the party claimed overall control of Cumbernauld and Kilsyth.

This success was to continue for much of the decade, and at the 1977 district elections the SNP saw victories at councils including East Kilbride and Falkirk and held the balance of power in Glasgow.[41] However, this level of support was not to last and by 1978 Labour revival was evident at three by-elections (Glasgow Garscadden, Hamilton and Berwick and East Lothian) as well as the regional elections.

This was to culminate when the party experienced a large drop in its support at the 1979 general election, precipitated by the party bringing down the incumbent Labour minority government following the controversial failure of that year's devolution referendum. Reduced to just 2 MPs, the successes of October 1974 were not to be surpassed until the 2015 general election.

In 1979 the party's MPs supported Margaret Thatcher's Motion of No Confidence in Jim Callaghan's Labour Government, with the motion carried by 311 votes to 310. Callaghan taunted the party that they were like “the turkeys who voted for Christmas” and the party went on to lose all but two of its seats in the subsequent election that ushered in 18 years of Tory rule.[42][43]

Factional divisions and infighting (1980s)

Following this defeat, a period of internal strife occurred within the party, culminating with the formation of two internal groups: the ultranationalist Siol nan Gaidheal[44][45] and left-wing 79 Group.[44] Traditionalists within the party, centred around Winnie Ewing, by this time an MEP, responded by establishing the Campaign for Nationalism in Scotland which sought to ensure that the primary objective of the SNP was campaigning for independence without a traditional left-right orientation, even though this would have undone the work of figures such as William Wolfe, who developed a clearly social democratic policy platform throughout the 1970s.

These events ensured the success of a leadership motion at the party's annual conference of 1982, in Ayr, despite the 79 Group being bolstered by the merger of Jim Sillars' Scottish Labour Party (SLP) although this influx of ex-SLP members further shifted the characteristics of the party leftwards. Despite this, traditionalist figure Gordon Wilson remained party leader through the electoral disappointments of 1983 and 1987, where he lost his own Dundee East seat won 13 years prior.

Through this period, Sillars' influence in the party grew, developing a clear socio-economic platform including Independence in Europe, reversing the SNP's previous opposition to membership of the then-EEC which had been unsuccessful in a 1975 referendum. This position was enhanced further by Sillars reclaiming Glasgow Govan in a by-election in 1988.

Despite this moderation, the party did not join Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens as well as civil society in the Scottish Constitutional Convention which developed a blueprint for a devolved Scottish Parliament due to the unwillingness of the convention to discuss independence as a constitutional option.[46]

First Salmond era (1990s)

Alex Salmond had been elected MP for Banff and Buchan in 1987, after the re-admittance of 79 Group members, and was able to seize the party leadership after Wilson's resignation in 1990 after a contest with Margaret Ewing. This was a surprise victory as Ewing had the backing of much of the party establishment, including Sillars and then-Party Secretary John Swinney. The defection of Labour MP Dick Douglas further evidenced the party's clear left-wing positioning, particularly regarding opposition to the poll tax.[47] Despite this, Salmond's leadership was unable to avert a fourth successive general election disappointment in 1992 with the party reduced back from 5 to 3 MPs.

The mid-90s offered some successes for the party, with North East Scotland being gained at the 1994 European elections and the party securing a by-election at Perth and Kinross in 1995 after a near-miss at Monklands East the previous year.

1997 offered the party's most successful general election for 23 years, although in the face of the Labour landslide the party was unable to match either of the two 1974 elections. That September, the party joined with the members of the Scottish Constitutional Convention in the successful Yes-Yes campaign in the devolution referendum which lead to the establishment of a Scottish Parliament with tax-varying powers.

By 1999, the first elections to the parliament were being held, although the party suffered a disappointing result, gaining just 35 MSPs in the face of Salmond's unpopular 'Kosovo Broadcast' which opposed NATO intervention in the country.[48]

Opposing Labour-Liberal Democrat coalitions (1999–2007)

This meant that the party began as the official opposition in the parliament to a Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition government. Salmond found the move to a more consensual politics difficult and sought a return to Westminster, resigning the leadership in 2000 with John Swinney, like Salmond a gradualist,[49] victorious in the ensuring leadership election.[50] Swinney's leadership proved ineffectual, with a loss of one MP in 2001 and a further reduction to 27 MSPs in 2003 despite the Officegate scandal unseating previous First Minister Henry McLeish.[51] However, the only parties to gain seats in that election were the Scottish Greens and the Scottish Socialist Party (SSP) which like the SNP support independence.[52][53]

Following an unsuccessful leadership challenge in 2003, Swinney stepped down following disappointing results in the European elections of 2004[54] with Salmond victorious in the subsequent leadership contest despite initially refusing to be candidate.[55] Nicola Sturgeon was elected Depute Leader and became the party's leader in the Scottish Parliament until Salmond was able to return at the next parliamentary election.

Salmond governments (2007–2014)

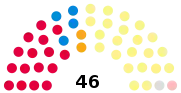

In 2007, the SNP emerged as the largest party in the Scottish Parliament with 47 of 129 seats, narrowly ousting Scottish Labour with 46 seats and Alex Salmond becoming First Minister after ousting the Liberal Democrats in Gordon. The Scottish Greens supported Salmond's election as First Minister, and his subsequent appointments of ministers, in return for early tabling of the climate change bill and the SNP nominating a Green MSP to chair a parliamentary committee.[56] Despite this, Salmond's minority government tended to strike budget deals with the Conservatives to stay in office.[57]

In May 2011, the SNP won an overall majority in the Scottish Parliament with 69 seats. This was a significant feat as the additional member system used for Scottish Parliament elections was specifically designed to prevent one party from winning an outright majority.[58][59] This was followed by a reverse in the party's previous opposition to NATO membership at the party's annual conference in 2012[60] despite Salmond's refusal to apologise for the Kosovo broadcast on the occasion of the Kosovo Declaration of Independence.[61]

This majority enabled the SNP government to hold a referendum on Scottish independence in 2014. The "No" vote prevailed in a close-fought campaign, prompting the resignation of First Minister Alex Salmond. Forty-five percent of Scottish voters cast their ballots for independence, with the "Yes" side receiving less support than late polling predicted.[62] Exit polling by Lord Ashcroft suggested that many No voters thought independence too risky,[63] while others voted for the Union because of their emotional attachment to Britain.[64] Older voters, women and middle class voters voted no in margins above the national average.[64]

Following the Yes campaign's defeat, Salmond resigned and Nicola Sturgeon won that year's leadership election unopposed.

Sturgeon years (2014 onwards)

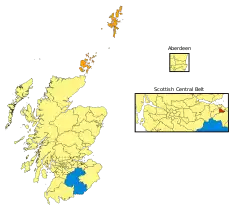

The SNP rebounded from their loss at the independence referendum at the 2015 UK general election eight months later, led by former Depute Leader Nicola Sturgeon. The party went from holding six seats in the House of Commons to 56, ending 51 years of dominance by the Scottish Labour Party. All but three of the fifty-nine constituencies in the country elected an SNP candidate in the party's most comprehensive electoral victory at any level.[65]

At the 2016 Scottish election, the SNP lost a net total of 6 seats, losing its overall majority in the Scottish Parliament, but returning for a third consecutive term as a minority government despite gaining an additional 1.1% of the constituency vote, for the party's best-ever result, from the 2011 election however 2.3% of the regional list vote. On the constituency vote, the SNP gained 11 seats from Labour, but lost the Edinburgh Southern constituency to Labour. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats each gained two constituency seats from the SNP on 2011 (Aberdeenshire West and Edinburgh Central for the Conservatives and Edinburgh Western and North East Fife for the Liberal Democrats).

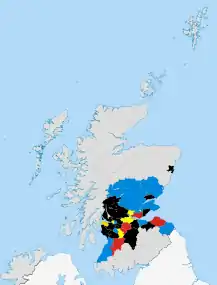

This election was followed by the 2016 European Union referendum after which the SNP joined with the Liberal Democrats and Greens to call for continued UK membership of the EU. Despite a consequential increase in the Conservative Party vote at the 2017 local elections[66] the SNP for the first time became the largest party in each of Scotland's four city councils: Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow, where a Labour administration was ousted after 37 years.[67]

At the 2017 UK general election, the SNP underperformed compared to polling expectations, losing 21 seats to bring their number of Commons seats down to 35 – however this was still the party's second-best result ever at the time.[68][69][70] This was largely attributed by many, including former Deputy First Minister John Swinney,[71] to their stance on holding a second Scottish independence referendum and saw a swing to the unionist parties, with seats being picked up by the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats and a reduction in their majorities in the other seats. Stephen Gethins, MP for North East Fife, came out of this election with a majority of just two votes to the Liberal Democrat candidate. High-profile losses included SNP Commons leader: Angus Robertson in Moray and former SNP leader and First Minister Alex Salmond in Gordon.

The SNP went on to achieve its best-ever European Parliament result in the final election before Brexit, the party taking its MEP total to 3 or half of Scottish seats and achieving a record vote share for the party. This was also the best performance of any party in the era of proportional elections to the European Parliament in Scotland. This was suggested as being due to the party's europhile sentiment during what amounted to a single-issue election, with parties that lacked a clear message performing poorly, such as Labour finishing in fifth place and losing all of their Scottish MEPs for the first time.

Later that year, the SNP experienced a surge in support at the 2019 general election, winning a 45.0% share of the vote and 48 seats, its second-best result ever. Although the party lost its most marginal seat to Wendy Chamberlain of the Liberal Democrats, it gained the seat of from Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson, along with 7 from the Conservatives and 6 from Labour. Swinson's loss triggered a leadership contest in the Liberal Democrats as a result. This victory was generally attributed to Sturgeon's cautious approach regarding holding a second independence referendum and a strong emphasis on retaining EU membership during the election campaign.[72] The following January, the strengthened Conservative government ensured that the UK left the European Union on 31 January 2020.

At the 2021 Scottish election, the SNP won 64 seats, one seat short of a majority, albeit achieving a record high number of votes, vote share and constituency seats, and leading to another minority government led by the SNP. Sturgeon emphasised after her party's victory that it would focus on controlling the COVID-19 pandemic as well as pushing for a second referendum on independence.[73]

Although in 2021 they won with a minority, a majority of MSPs elected had come from parties that supported Scottish independence, this prompted negotiations started between the SNP and the Scottish Green Party to secure some form of deal that would see Green ministers appointed to government and the Scottish Greens backing SNP policies, with hopes that this united front on independence would solidify the SNP's mandate for the second independence referendum. The Alba Party, led by former First Minister and SNP leader Alex Salmond, did not achieve an electoral breakthrough at Holyrood as expected, however they intended to cooperate to create a "super majority" for Scottish independence if elected. The Third Sturgeon government was formed with Green support.[74]

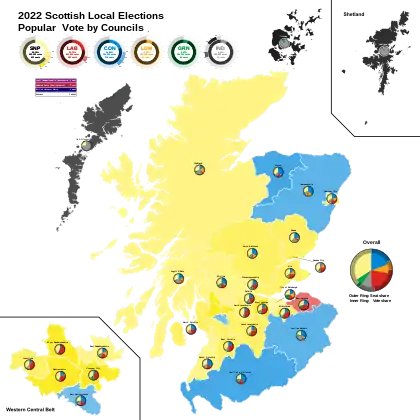

In the 2022 Scottish local elections, the SNP remained as the biggest party, winning a record number of councillors and securing majority control of Dundee.[75]

Constitution and structure

The local Branches are the primary level of organisation in the SNP. All of the Branches within each Scottish Parliament constituency form a Constituency Association, which coordinates the work of the Branches within the constituency, coordinates the activities of the party in the constituency and acts as a point of liaison between an MSP or MP and the party. Constituency Associations are composed of delegates from all of the Branches within the constituency.

The annual National Conference is the supreme governing body of the SNP and is responsible for determining party policy and electing the National Executive Committee. The National Conference is composed of:

- delegates from every Branch and Constituency Association

- the members of the National Executive Committee

- every SNP MSP and MP

- all SNP councillors

- delegates from each of the SNP's Affiliated Organisations (Young Scots for Independence, SNP Students, SNP Trade Union Group, the Association of Nationalist Councillors, the Disabled Members Group, the SNP BAME Network, Scots Asians for Independence, and Out for Independence)

There are also regular meetings of the National Assembly, which provides a forum for detailed discussions of party policy by party members.

Membership

The SNP experienced a large surge in membership following the 2014 Scottish independence referendum.[76] In 2013 the party's membership stood at just 20,000,[77] but that number had swelled to over 100,000 by 2015.[78] Annual accounts submitted by the party to the Electoral Commission showed the SNP to have over 119,000 members in 2021.[79] By the end of 2021, the party reported to have 103,884 members.[1]

European affiliation

The SNP retains close links with Plaid Cymru, its counterpart in Wales. MPs from both parties co-operate closely with each other and work as a single parliamentary group within the House of Commons. Both the SNP and Plaid Cymru are members of the European Free Alliance (EFA), a European political party comprising regionalist political parties. The EFA co-operates with the larger European Green Party to form The Greens–European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) group in the European Parliament.

Before its affiliation with The Greens–European Free Alliance, the SNP had previously been allied with the European Progressive Democrats (1979–1984), Rainbow Group (1989–1994) and European Radical Alliance (1994–1999).

As the UK is no longer a member of the EU, the SNP has no MEPs. In the 2019 European Parliament election, the SNP won 3 out of 6 seats in Scotland.

Policies

Ideological foundations

The Scottish National Party did not have a clear ideological position until the 1970s, when it sought to explicitly present itself as a social democratic party in terms of party policy and publicity.[80][81] During the period from its foundation until the 1960s, the SNP was essentially a moderate centrist party.[80] Debate within the party focused more on the SNP being distinct as an all-Scotland national movement, with it being neither of the left nor the right, but constituting a new politics that sought to put Scotland first.[81][82]

The SNP was formed through the merger of the centre-left National Party of Scotland (NPS) and the centre-right Scottish Party.[81] The SNP's founders were united over self-determination in principle, though not its exact nature, or the best strategic means to achieve self-government. From the mid-1940s onwards, SNP policy was radical and redistributionist concerning land and in favour of 'the diffusion of economic power', including the decentralisation of industries such as coal to include the involvement of local authorities and regional planning bodies to control industrial structure and development.[80] Party policies supported the economic and social policy status quo of the post-war welfare state.[80][83]

By the 1960s, the SNP was starting to become defined ideologically, with a social democratic tradition emerging as the party grew in urban, industrial Scotland, and its membership experienced an influx of social democrats from the Labour Party, the trade unions and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[84][85] The emergence of Billy Wolfe as a leading figure in the SNP also contributed to the leftwards shift. By this period, the Labour Party was also the dominant party in Scotland, in terms of electoral support and representation. Targeting Labour through emphasising left-of-centre policies and values was therefore electorally logical for the SNP, as well as tying in with the ideological preferences of many new party members.[85] In 1961, the SNP conference expressed the party's opposition to the siting of the US Polaris submarine base at the Holy Loch. This policy was followed in 1963 by a motion opposed to nuclear weapons: a policy that has remained in place ever since.[86] The 1964 policy document, SNP & You, contained a clear centre-left policy platform, including commitments to full employment, government intervention in fuel, power and transport, a state bank to guide economic development, encouragement of cooperatives and credit unions, extensive building of council houses (social housing) by central and local government, pensions adjusted to cost of living, a minimum wage and an improved national health service.[80]

The 1960s also saw the beginnings of the SNP's efforts to establish an industrial organisation and mobilise amongst trade unionists in Scotland, with the establishment of the SNP Trade Union Group, and identifying the SNP with industrial campaigns, such as the Upper-Clyde Shipbuilders Work-in and the attempt of the workers at the Scottish Daily Express to run as a co-operative.[80] For the party manifestos for the two 1974 general elections, the SNP finally self-identified as a social democratic party, and proposed a range of social democratic policies.[87][88] There was also an unsuccessful proposal at the 1975 party conference to rename the party as the Scottish National Party (Social Democrats).[89] In the UK-wide referendum on Britain's membership of the European Economic Community (EEC) in the same year as the aforementioned attempted name change, the SNP campaigned for Britain to leave the EEC.[90][91]

There were further ideological and internal struggles after 1979, with the 79 Group attempting to move the SNP further to the left, away from being what could be described a "social-democratic" party, to an expressly "socialist" party. Members of the 79 Group – including future party leader and First Minister Alex Salmond – were expelled from the party. This produced a response in the shape of the Campaign for Nationalism in Scotland from those who wanted the SNP to remain a "broad church", apart from arguments of left vs. right. The 1980s saw the SNP further define itself as a party of the political left, such as campaigning against the introduction of the poll tax in Scotland in 1989; one year before the tax was imposed on the rest of the UK.[80]

Ideological tensions inside the SNP are further complicated by arguments between the so-called SNP gradualists and SNP fundamentalists. In essence, gradualists seek to advance Scotland to independence through further devolution, in a "step-by-step" strategy. They tend to be in the moderate left grouping, though much of the 79 Group was gradualist in approach. However, this 79 Group gradualism was as much a reaction against the fundamentalists of the day, many of whom believed the SNP should not take a clear left or right position.[80]

Economic policies

During the 1970s the SNP campaigned widely on the political slogan It's Scotland's oil, where it was argued that the discovery of North Sea oil off the coast of Scotland, and the revenue that it created would not benefit Scotland to any significant degree while Scotland remained part of the United Kingdom.

The Sturgeon Government in 2017 adjusted income tax rates so that low earners would pay less and those earning more than £33,000 a year would pay more.[92] Previously the party had replaced the flat rate Stamp Duty with the LBTT, which uses a graduated tax rate.[93] Whilst in government, the party was also responsible for the establishment of Revenue Scotland to administer devolved taxation.

Having previously defined itself in opposition to the poll tax[80] the SNP has also championed progressive taxation at a local level. Despite pledging to introduce a local income tax[94] the Salmond Government found itself unable to replace the council tax and the party has, particularly since the ending of the council tax freeze[95] under Nicola Sturgeon's leadership, committing to increasing the graduated nature of the tax.[96] Conversely, the party has also supported capping and reducing Business Rates in an attempt to support small businesses.[97]

It has been noted that the party contains a broader spectrum of opinion regarding economic policy than most political parties in the UK due to its status as "the only viable vehicle for Scottish independence",[98] with the party's parliamentary group at Westminster in 2016 including socialists such as Tommy Sheppard and Mhairi Black, capitalists such as Stewart Hosie and former Conservative, Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh.[98][99]

Social policies

When Robin Cook MP moved an amendment to legalise homosexual acts to the Bill which became the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1980, he stated "The clause bears the names of hon. Members from all three major parties. I regret that the only party represented among Scottish Members of Parliament from which there has been no support for the clause is the Scottish National Party. I am pleased to see both representatives of that party in their place, and I hope to convert them in the remainder of my remarks."[100] When the amendment came to a vote, the SNP's MPs Gordon Wilson and Donald Stewart both voted against the decriminalisation of homosexual acts.[101]

Under Sturgeon's leadership, Scotland was twice in succession named the best country in Europe for LGBT+ legal equality.[102] The party is considered very tolerant of gays, lesbians and bisexuals - something that historically was not the case, as stated above.[103][104]

Party policy aims to introduce gender self-identification[105] to allow an easier process of gender recognition for transgender community.[106] However, the policy is highly controversial within the SNP and many of the party's social conservatives have expressed concerns that the reforms would be open to abuse and allow predatory men into women's spaces.[103][107] The Scottish Government paused the legislation in order to find "maximum consensus" on the issue[103] and commentators described the issue as having divided the SNP like no other, with many dubbing the debate a "civil war".[108][109][110] In January 2021 a former trans officer in the SNP's LGBT wing, Teddy Hopes, quit the party, describing it was one of the “core hubs of transphobia in Scotland".[111] Large numbers of LGBT activists followed suit and Sturgeon released a video message in which she said that transphobia is "not acceptable" and that she hoped they would one day rejoin the party.[112][113]

Particularly since Nicola Sturgeon's elevation to First Minister the party has highlighted its commitments to gender equality – with her first act being to appoint a gender balanced cabinet.[114] The SNP have also taken steps to implement all-women shortlists whilst Sturgeon has introduced a mentoring scheme[115] to encourage women's political engagement.[116]

The SNP supports multiculturalism[117] with Scotland receiving thousands of refugees from the Syrian Civil War.[118] To this end it has been claimed that refugees in Scotland are better supported than those in England.[119] More generally, the SNP seeks to increase immigration to combat a declining population[120] and calling for a separate Scottish visa even within the UK.[121]

Foreign and defence policies

.jpg.webp)

Despite traditionally supporting military neutrality[122] the SNP's policy has in recent years moved to support both the Atlanticist and Europeanist traditions. This is particularly evident in the conclusion of the NATO debate within the party in favour of those who support membership of the military alliance.[123] This is despite the party's continuing opposition to Scotland hosting nuclear weapons and then-leader Salmond's criticism of both the Kosovo intervention[124] and the Iraq War.[125] The party has placed an emphasis on developing positive relations with the United States in recent years[126] despite a lukewarm reaction to the election of part-Scottish American Donald Trump as President due to long running legal disputes.[127]

Having opposed continued membership in the 1975 referendum, the party has supported membership of the European Union since the adoption of the Independence in Europe policy during the 1980s. Consequentially, the SNP supported remaining within the EU during the 2016 referendum where every Scottish council area backed this position.[128] Consequently, the party opposed Brexit and sought a further referendum on the withdrawal agreement,[129] ultimately unsuccessfully. The SNP would like to see an independent Scotland as a member of the European Union and NATO[130] and has left open the prospect of an independent Scotland joining the euro.[131]

The SNP has also taken a stance against Russian interference abroad – the party supporting the enlargement of the EU and NATO to areas such as the Western Balkans and Ukraine to counter this influence.[132][133] The party called for repercussions for Russia regarding the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal[134] and has criticised former leader Alex Salmond for broadcasting a chat show on Kremlin-backed[135] network RT.[136] Consequently, party representatives have expressed support for movements such as Euromaidan that support the independence of countries across Eastern Europe.[137]

The party have supported measures including foreign aid which seek to facilitate international development[138] through various charitable organisations.[139] In recognition of Scotland's historic links to the country, these programmes are mostly focused in Malawi[140] in common with previous Scottish governments. With local authorities across the country, including Glasgow City Council being involved in this partnership since before the SNP took office in 2007.[141]

Health and education policies

The SNP have pledged to uphold the public service nature of NHS Scotland and are consequently opposed to any attempts at privatisation of the health service,[142] including any inclusion in a post-Brexit trade deal with the United States. The party has been fond of increasing provision under the NHS with the introduction of universal baby boxes based on the Finnish scheme.[143] This supported child development alongside other commitments including the expansion of free childcare for children younger than school age and the introduction of universal free school meals in the first three years of school.[144]

Previously, SNP governments have abolished hospital parking charges[145] as well as prescription charges[146] in efforts to promote enhanced public health outcomes by increasing access to care and treatment. Furthermore, during Sturgeon's premiership, Scotland became the first country in the world to introduce alcohol minimum unit pricing to counter alcohol problems.[147] Recently, the party has also committed to providing universal access to sanitary products[148] and the liberalisation of drugs policy[149] through devolution, in an effort to increase access to treatment and improve public health outcomes. Between 2014 and 2019 the party slashed the budget for drug and alcohol treatments by 6.3%[150] - a cut that has been linked with Scotland recording the highest number of drug deaths per head in Europe.[151]

The party aspires to promote universal access to education, with one of the first acts of the Salmond government being to abolish tuition fees[152] - although it has also introduced a cap on the number of Scots who can attend university and cut funding for further education colleges.[153][154] More recently, the party has turned its attention to widening access to higher education[155] with Nicola Sturgeon stating that education is her number one priority.[156] At school level, the Curriculum for Excellence is currently undergoing a review.[157]

Constitution policies

The foundations of the SNP are a belief that Scotland would be more prosperous by being governed independently from the United Kingdom, although the party was defeated in the 2014 referendum on this issue.[158] The party has since sought to hold a second referendum at some point in the future, perhaps related to the outcome of Brexit,[159] as the party sees a referendum as the only route to independence. In 2016 the party convened the Sustainable Growth Commission to advise on the economy and currency of an independent Scotland. Although the Sustainable Growth Commission's report, published in 2018, divides opinion it contains the party's official economic recommendations in the event of independence. The party is constitutionalist and as such rejects holding such a referendum unilaterally or any course of actions that could lead to comparisons with cases such as Catalonia[160] with the party seeing independence as a process that should be undertaken through a consensual process alongside the UK Government. As part of this process towards independence, the party supports increased devolution to the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government, particularly in areas such as welfare and immigration.[161]

Official SNP policy is supportive of the monarchy. Many party members are republicans but party leader, Nicola Sturgeon, believes it is a "model with many merits", although she has proposed reducing the funds spent on the royal family.[162][163] Separately, the SNP has always opposed the UK's unelected upper house and would like to see both it and the House of Commons elected by a form of proportional representation.[164] The party also supports the introduction of a codified constitution, either for an independent Scotland or the UK as a whole,[165] going as far as producing a proposed interim constitution for Scotland during the independence referendum campaign.[166]

Fundamentalists and gradualists

There have always been divisions within the party on how to achieve Scottish independence, with one wing described as 'fundamentalists' and the other 'gradualists'.

The SNP leadership generally subscribes to the gradualist viewpoint, that being the idea that independence can be won by the accumulation by the Scottish Parliament of powers that the UK Parliament currently has over time.

Fundamentalism stands in opposition to the so-called gradualist point of view, which believes that the SNP should emphasise independence more widely to achieve it. The argument goes that if the SNP is unprepared to argue for its central policy then it is unlikely ever to persuade the public of its worthiness.[167]

Leadership

Leader of the Scottish National Party

| Leader (birth-death) |

Portrait | Political Office | Took Office | Left Office |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sir Alexander MacEwen (1875–1941) |

|

Provost of Inverness (1925–1931) Inverness Town Councillor (1908–1931) Inverness-shire County Councillor for Benbecula (1931–1941)[168] Candidate for Western Isles (1935) former member, Liberal Party founding member, Scottish Party |

7 April 1934 | 1936 |

| Prof Andrew Dewar Gibb KC (1888–1974) |

Candidate for Combined Scottish Universities (1936, 1938) former member, Unionist Party; Scottish Party |

1936 | 1940 | |

| William Power (1873–1951) |

Candidate for Argyllshire (1940) | 1940 | 30 May 1942 | |

| Douglas Young (1913–1973) |

|

Candidate for Kirkcaldy Burghs (1944) | 30 May 1942 | 9 June 1945 |

| Prof Bruce Watson (1910–1988) |

9 June 1945 | May 1947 | ||

| Robert McIntyre (1913–1998) |

MP for Motherwell (1945) Provost of Stirling (1967–1975) Stirling Burgh Councillor (1956–1975) former member, Labour Party |

May 1947 | June 1956 | |

| James Halliday (1927–2013) |

Candidate for Stirling and Falkirk (1955 and 1959) Candidate for West Fife (1970) |

June 1956 | 5 June 1960 | |

| Arthur Donaldson (1901–1993) |

|

Angus County Councillor (1946–1955) Forfar Town Councillor (1945–1968) former member, National Party of Scotland |

5 June 1960 | 1 June 1969 |

| William Wolfe (1924–2010) |

.gif) |

Candidate for West Lothian (1970–79) | 1 June 1969 | 15 September 1979 |

| Gordon Wilson (1938–2017) |

|

MP for Dundee East (1974–1987) | 15 September 1979 | 22 September 1990 |

| The Right Hon. Alex Salmond (born 1954) (1st Term) |

|

MP for Banff and Buchan (1987–2010) MSP for Banff and Buchan (1999–2001) |

22 September 1990 | 26 September 2000 |

| John Swinney (born 1964) |

|

Deputy First Minister (since 2014) MSP for Perthshire North (since 2011) MSP for North Tayside (1999–2011) MP for North Tayside (1997–2001) |

26 September 2000 | 3 September 2004 |

| The Right Hon. Alex Salmond (born 1954) (2nd Term) |

|

First Minister (2007–2014) MSP for Aberdeenshire East (2011–2016) MSP for Gordon (2007–2011) MP for Gordon (2015–2017) |

3 September 2004 | 14 November 2014 |

| The Right Hon. Nicola Sturgeon (born 1970) |

|

First Minister (since 2014) Deputy First Minister (2007–2014) MSP for Glasgow Southside (since 2011) MSP for Glasgow Govan (2007–2011) MSP for Glasgow (1999–2007) |

14 November 2014 | Incumbent |

Depute Leader of the Scottish National Party

| Depute Leader (birth-death) |

Portrait | Political Office | Took Office | Left Office |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandy Milne (1920–1984) |

Councillor for Stirling (1950s) | 17 May 1964[169] | 5 June 1966[169] | |

| William Wolfe (1924–2010) |

.gif) |

Candidate for West Lothian (1966) | 5 June 1966[169] | 1 June 1969 |

| George Leslie (born 1936) |

Councillor for Calderwood/St Leonards (1974–1978) | 1 June 1969 | 30 May 1971[169] | |

| Douglas Henderson (1935–2006) (1st Term) |

MP for East Aberdeenshire (1974–1979) | 30 May 1971[169] | 3 June 1973[169] | |

| Gordon Wilson (1938–2017) |

MP for Dundee East (1974–1987) | 3 June 1973[169] | 2 June 1974[169] | |

| Margo MacDonald (1943–2014) |

|

MSP for Lothian (1999–2014) MP for Glasgow Govan (1973–1974) |

2 June 1974[169] | 15 September 1979[169] |

| Douglas Henderson (1935–2006) (2nd Term) |

MP for East Aberdeenshire (1974–1979) | 15 September 1979[169] | 30 May 1981[169] | |

| Jim Fairlie (born 1940) |

Candidate for Dunfermline West (1983) | 30 May 1981[169] | 15 September 1984[169] | |

| Margaret Ewing (1945–2006) |

MSP for Moray (1999–2006) MP for Moray (1987–2001) MP for East Dunbartonshire (1974–1979) |

15 September 1984[169] | 26 September 1987[169] | |

| The Right Hon. Alex Salmond (born 1954) |

|

MP for Banff and Buchan (1987–2010) | 26 September 1987[169] | 22 September 1990 |

| Alasdair Morgan (born 1945) |

MSP for South of Scotland (2003–2011) MSP for Galloway and Upper Nithsdale (1999–2003) MP for Galloway and Upper Nithsdale (1997–2001) |

22 September 1990 | 22 September 1991[169] | |

| Jim Sillars (born 1937) |

MP for Glasgow Govan (1988–1992) MP for South Ayrshire (1970–1979) |

22 September 1991[169] | 25 September 1992[169] | |

| Allan Macartney (1941–1998) |

MEP for North East Scotland (1994–1998) | 25 September 1992[169] | 25 August 1998[169] | |

| John Swinney (born 1964) |

|

MSP for Perthshire North (since 2011) MSP for North Tayside (1999–2011) MP for North Tayside (1997–2001) |

25 August 1998[169] | 26 September 2000 |

| Roseanna Cunningham (born 1951) |

|

MSP for Perthshire South and Kinross-shire (2011–2021) MSP for Perth (1999–2011) MP for Perth (1997–2001) MP for Perth and Kinross (1995–1997) |

26 September 2000 | 3 September 2004 |

| The Right Hon. Nicola Sturgeon (born 1970) |

|

Deputy First Minister (2007–2014) MSP for Glasgow Southside (since 2011) MSP for Glasgow Govan (2007–2011) MSP for Glasgow (1999–2007) |

3 September 2004 | 14 November 2014 |

| The Right Hon. Stewart Hosie (born 1963) |

|

MP for Dundee East (since 2005) | 14 November 2014 | 13 October 2016 |

| The Right Hon. Angus Robertson (born 1969) |

|

MSP for Edinburgh Central (since 2021) MP for Moray (2001–2017) |

13 October 2016 | 8 June 2018 |

| Keith Brown (born 1961) |

|

MSP for Clackmannanshire and Dunblane (since 2011) MSP for Ochil (2007–2011) Leader of Clackmannanshire Council (2003–2007) Councillor for Alva (1999–2007) |

8 June 2018 | Incumbent |

.jpg.webp)

President of the Scottish National Party

- James Graham, 6th Duke of Montrose and Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham (joint), 1934–1936

- Roland Muirhead, 1936–1950

- Tom Gibson, 1950–1958

- Robert McIntyre, 1958–1980

- William Wolfe, 1980–1982

- Donald Stewart, 1982–1987

- Winnie Ewing, 1987–2005

- Ian Hudghton, 2005–2020

- Michael Russell, 2020–present

National Secretary of the Scottish National Party

- John MacCormick, 1934–1942

- Robert McIntyre, 1942–1947

- Mary Fraser Dott, 1947–1951

- Robert Curran, 1951–1954

- John Smart, 1954–1963

- Malcolm Shaw, 1963–1964

- Gordon Wilson, 1964–1971

- Muriel Gibson, 1971–1972

- Rosemary Hall, 1972–1975

- Muriel Gibson, 1975–1977

- Chrissie MacWhirter, 1977–1979

- Iain Murray, 1979–1981

- Neil MacCallum, 1981–1986

- John Swinney, 1986–1992

- Alasdair Morgan, 1992–1997

- Stewart Hosie, 1999–2003

- Alasdair Allan, 2003–2006

- Duncan Ross, 2006–2009

- William Henderson, 2009–2012

- Patrick Grady, 2012–2016

- Angus MacLeod, 2016–2020

- Stewart Stevenson, 2020–2021

- Lorna Finn, 2021-present

Leader of the parliamentary party, Scottish Parliament

- Alex Salmond (Banff and Buchan), 1999–2000

- John Swinney (North Tayside), 2000–2004

- Nicola Sturgeon (Glasgow), 2004–2007

- Alex Salmond (Aberdeenshire East), 2007–2014

- Nicola Sturgeon (Glasgow Southside) 2014–present

Leader of the parliamentary party, House of Commons

- Donald Stewart (Western Isles), 1974–1987

- Margaret Ewing (Moray), 1987–1999

- Alasdair Morgan (Galloway and Upper Nithsdale), 1999–2001

- Alex Salmond (Banff and Buchan), 2001–2007

- Angus Robertson (Moray), 2007–2017

- Ian Blackford (Ross, Skye and Lochaber), 2017–present

Chief Executive Officer

- Michael Russell, 1994–1999

- Peter Murrell, 1999–present

Current SNP Council Leaders

- Clackmannanshire: Les Sharp (Clackmannanshire West), since 2017

- Dundee City: John Alexander (Strathmartine), since 2017

- East Ayrshire: Douglas Reid (Kilmarnock West and Crosshouse), since 2007

- East Renfrewshire: Tony Buchanan (Newton Mearns North and Neilston), since 2017

- City of Edinburgh: Adam McVey (Leith), since 2017

- Falkirk: Cecil Meiklejohn (Falkirk North), since 2017

- Fife: David Alexander (Leven, Kennoway and Largo), since 2017

- Glasgow City: Susan Aitken (Langside), since 2017

- Moray: Graham Leadbitter (Elgin South), since 2018

- Renfrewshire: Iain Nicolson (Erskine and Inchinnan), since 2017

- South Ayrshire: Douglas Campbell (Ayr North), since 2017

- South Lanarkshire: John Ross (Hamilton South), since 2017

- Stirling: Scott Farmer (Stirling West), since 2017

- West Dunbartonshire: Jonathon McColl (Lomond), since 2017

Government Ministers and Shadow Cabinet

Scottish Parliament

As of May 2021, the Cabinet of the Scottish Government is as follows:

| Portfolio | Minister | Image |

|---|---|---|

| First Minister | The Right Hon. Nicola Sturgeon MSP for Glasgow Southside |

|

| Deputy First Minister | John Swinney MSP for Perthshire North |

|

| Cabinet Secretary for Covid Recovery | ||

| Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Economy | Kate Forbes MSP for Skye, Lochaber and Badenoch |

|

| Cabinet Secretary for Justice | Keith Brown MSP for Clackmannanshire and Dunblane |

|

| Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills | Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP for Dunfermline |

|

| Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care | Humza Yousaf MSP for Glasgow Pollok |

|

| Cabinet Secretary for Net Zero, Energy and Transport | Michael Matheson MSP for Falkirk West |

|

| Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, External Affairs and Culture | The Right Hon. Angus Robertson MSP for Edinburgh Central |

|

| Cabinet Secretary for Social Justice, Housing and Local Government | Shona Robison MSP for Dundee City East |

|

| Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs and Islands | Mairi Gougeon MSP for Angus North and Mearns |

|

House of Commons

As of February 2021, the Shadow Cabinet of the SNP in Westminster is as follows.[171]

| Portfolio | Shadow Secretary/Minister | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Westminster Leader | The Right Hon. Ian Blackford MP for Ross, Skye and Lochaber |

|

| Westminster Deputy Leader Shadow Minister for Women and Equalities |

Kirsten Oswald MP for East Renfrewshire |

|

| Shadow Chancellor | Alison Thewliss MP for Glasgow Central |

|

| Shadow Foreign Secretary | Alyn Smith MP for Stirling |

|

| Shadow Home Secretary | Stuart McDonald MP for Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for International Trade | Drew Hendry MP for Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Shadow Minister for Europe |

Philippa Whitford MP for Central Ayrshire |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Work and Pensions | David Linden MP for Glasgow East |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy | Stephen Flynn MP for Aberdeen South |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Scotland | Mhairi Black MP for Paisley and Renfrewshire South |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Justice and Immigration | Anne McLaughlin MP for Glasgow North East |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport | John Nicolson MP for Ochil and South Perthshire |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government | Patricia Gibson MP for North Ayrshire and Arran |

|

| Shadow Secretary for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | Deidre Brock MP for Edinburgh North and Leith |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Northern Ireland and Wales | Richard Thomson MP for Gordon |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Defence | Stewart McDonald MP for Glasgow South |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Transport | Gavin Newlands MP for Paisley and Renfrewshire North |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for Education Shadow Minister for Military Personnel and Veterans |

Carol Monaghan MP for Glasgow North West |

|

| Shadow Secretary of State for International Development | Chris Law MP for Dundee West |

|

| Shadow Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster Shadow Minister for the Cabinet Office |

Stewart Hosie MP for Dundee East |

|

| Shadow Leader of the House of Commons | Pete Wishart MP for Perth and North Perthshire |

|

| Shadow Minister for Energy and Climate Change | Alan Brown MP for Kilmarnock and Loudoun |

|

| Shadow Attorney General | Angela Crawley MP for Lanark and Hamilton East |

|

Present elected representatives

Councillors

The SNP had 431 councillors in Local Government elected from the 2017 Scottish local elections.

Electoral performance

Scottish Parliament

| Election[172] | Leader | Constituency | Regional | Total seats | +/– | Pos. | Government | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vote | % | Seats | Vote | % | Seats | ||||||

| 1999 | Alex Salmond | 672,768 | 28.7 | 7 / 73 |

638,644 | 27.3 | 28 / 56 |

35 / 129 |

Opposition | ||

| 2003 | John Swinney | 455,722 | 23.7 | 9 / 73 |

399,659 | 20.9 | 18 / 56 |

27 / 129 |

Opposition | ||

| 2007 | Alex Salmond | 664,227 | 32.9 | 21 / 73 |

633,611 | 31.0 | 26 / 56 |

47 / 129 |

Minority | ||

| 2011 | 902,915 | 45.4 | 53 / 73 |

876,421 | 44.0 | 16 / 56 |

69 / 129 |

Majority | |||

| 2016 | Nicola Sturgeon | 1,059,898 | 46.5 | 59 / 73 |

953,587 | 41.7 | 4 / 56 |

63 / 129 |

Minority | ||

| 2021 | 1,291,204 | 47.7 | 62 / 73 |

1,094,374 | 40.3 | 2 / 56 |

64 / 129 |

Minority | |||

House of Commons

| Election[172] | Leader | Scotland | +/– | Position | Government | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Seats | ||||||

| 1935 | Sir Alexander MacEwen | 29,517 | 1.1 | 0 / 71 |

— | |||

| 1945 | Douglas Young | 26,707 | 1.2 | 0 / 71 |

— | |||

| 1950 | Robert McIntyre | 9,708 | 0.4 | 0 / 71 |

— | |||

| 1951 | 7,299 | 0.3 | 0 / 71 |

— | ||||

| 1955 | 12,112 | 0.5 | 0 / 71 |

— | ||||

| 1959 | Jimmy Halliday | 21,738 | 0.5 | 0 / 71 |

— | |||

| 1964 | Arthur Donaldson | 64,044 | 2.4 | 0 / 71 |

— | |||

| 1966 | 128,474 | 5.0 | 0 / 71 |

— | ||||

| 1970 | William Wolfe | 306,802 | 11.4 | 1 / 71 |

Opposition | |||

| Feb 1974 | 633,180 | 21.9 | 7 / 71 |

Opposition | ||||

| Oct 1974 | 839,617 | 30.4 | 11 / 71 |

Opposition | ||||

| 1979 | 504,259 | 17.3 | 2 / 71 |

Opposition | ||||

| 1983 | Gordon Wilson | 331,975 | 11.7 | 2 / 72 |

Opposition | |||

| 1987 | 416,473 | 14.0 | 3 / 72 |

Opposition | ||||

| 1992 | Alex Salmond | 629,564 | 21.5 | 3 / 72 |

Opposition | |||

| 1997 | 621,550 | 22.1 | 6 / 72 |

Opposition | ||||

| 2001 | John Swinney | 464,314 | 20.1 | 5 / 72 |

Opposition | |||

| 2005 | Alex Salmond | 412,267 | 17.7 | 6 / 59 |

Opposition | |||

| 2010 | 491,386 | 19.9 | 6 / 59 |

Opposition | ||||

| 2015 | Nicola Sturgeon | 1,454,436 | 50.0 | 56 / 59 |

Opposition | |||

| 2017 | 959,090 | 36.9 | 35 / 59 |

Opposition | ||||

| 2019 | 1,242,380 | 45.0 | 48 / 59 |

Opposition | ||||

Local councils

| Election[172] | Votes | Seats | +/– | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Pos. | ||||

| 1995 | 26.1 | 181 / 1,222 |

|||

| 1999 | 28.9 | 201 / 1,222 |

|||

| 2003 | 24.1 | 171 / 1,222 |

|||

| 2007 | 29.7 | 363 / 1,222 |

Single transferable vote introduced. | ||

| 2012 | 32.3 | 425 / 1,223 |

|||

| 2017 | 32.3 | 431 / 1,227 |

|||

| 2022 | 34.1 | 453 / 1,226 |

|||

Results by council (2022)

| Council | Votes[173] | Seats | Administration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Pos. | |||

| Aberdeen City | 35.0 | 20 / 45 |

SNP–Lib Dem | |

| Aberdeenshire | 30.8 | 21 / 70 |

Opposition | |

| Angus | 38.3 | 13 / 28 |

SNP–Independent | |

| Argyll and Bute | 31.0 | 12 / 36 |

Opposition | |

| Clackmannanshire | 39.4 | 9 / 18 |

Minority | |

| Dumfries and Galloway | 28.2 | 11 / 43 |

SNP–Labour | |

| Dundee City | 41.4 | 15 / 29 |

Majority | |

| East Ayrshire | 37.9 | 14 / 32 |

Minority | |

| East Dunbartonshire | 30.4 | 8 / 22 |

Minority | |

| East Lothian | 28.2 | 7 / 22 |

Opposition | |

| East Renfrewshire | 28.6 | 6 / 18 |

Opposition | |

| City of Edinburgh | 25.9 | 19 / 63 |

Opposition | |

| Falkirk | 39.7 | 12 / 30 |

Minority | |

| Fife | 36.9 | 34 / 75 |

Opposition | |

| Glasgow City | 35.5 | 37 / 85 |

Minority | |

| Highland | 30.1 | 22 / 74 |

SNP–Independent | |

| Inverclyde | 37.7 | 8 / 22 |

Opposition | |

| Midlothian | 37.6 | 8 / 18 |

Minority | |

| Moray | 36.0 | 8 / 26 |

Opposition | |

| Na h-Eileanan Siar | 21.3 | 6 / 29 |

Opposition | |

| North Ayrshire | 36.3 | 12 / 33 |

Minority | |

| North Lanarkshire | 43.6 | 36 / 77 |

Minority | |

| Orkney | 0.0 | 0 / 21 |

Opposition | |

| Perth and Kinross | 36.6 | 16 / 40 |

Minority | |

| Renfrewshire | 41.7 | 21 / 43 |

Minority | |

| Scottish Borders | 21.0 | 9 / 34 |

Opposition | |

| Shetland | 4.4 | 1 / 23 |

Opposition | |

| South Ayrshire | 33.4 | 9 / 28 |

Opposition | |

| South Lanarkshire | 36.9 | 27 / 64 |

Opposition | |

| Stirling | 33.3 | 8 / 23 |

Opposition | |

| West Dunbartonshire | 42.5 | 9 / 22 |

Opposition | |

| West Lothian | 37.9 | 15 / 33 |

Opposition | |

European Parliament (1979–2020)

.svg.png.webp)

| Election[172] | Group | Votes |

Seats | +/– | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Pos. | |||||||

| 1979 | EPD | 19.4 | 1 / 8 |

|||||

| 1984 | EDA | 17.8 | 1 / 8 |

|||||

| 1989 | RBW | 25.6 | 1 / 8 |

|||||

| 1994 | ERA | 32.6 | 2 / 8 |

|||||

| 1999 | G-EFA | 27.2 | 2 / 8 |

Proportional representation introduced. | ||||

| 2004 | 19.7 | 2 / 7 |

||||||

| 2009 | 29.1 | 2 / 6 |

||||||

| 2014 | 29.0 | 2 / 6 |

||||||

| 2019 | 37.8 | 3 / 6 |

Last European election before Brexit. | |||||

Two-tier local councils (1975–1996)

| District Councils | Regional and Island Councils | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election[172] | Votes | Seats | Councils | Election[172] | Votes | Seats | Councils | ||

| % | Pos. | % | Pos. | ||||||

| 1974 | 12.4 | 62 / 1,158 |

1 / 53 |

1974 | 12.6 | 18 / 524 |

0 / 12 | ||

| 1977 | 24.2 | 170 / 1,158 |

5 / 53 |

1978 | 20.9 | 18 / 524 |

0 / 12 | ||

| 1980 | 15.5 | 54 / 1,158 |

0 / 53 |

1982 | 13.4 | 23 / 524 |

0 / 12 | ||

| 1984 | 11.7 | 59 / 1,158 |

1 / 53 |

1986 | 18.2 | 36 / 524 |

0 / 12 | ||

| 1988 | 21.3 | 113 / 1,158 |

1 / 53 |

1990 | 21.8 | 42 / 524 |

0 / 12 | ||

| 1992 | 24.3 | 150 / 1,158 |

1 / 53 |

1994 | 26.8 | 73 / 453 |

0 / 12 | ||

See also

- Bo'ness Branch SNP

- Culture of Scotland

- Politics of Scotland

- History of Scottish devolution

- It's Scotland's oil

- Radio Free Scotland

- Scottish Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

- The National (Scotland)

References

- "Annual Accounts 2021", The Electoral Commission, 30 June 2022, retrieved 17 August 2022

- Hassan, Gerry (2009), The Modern SNP: From Protest to Power, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 5, 9

- Christopher Harvie (12 August 2004). Scotland and Nationalism: Scottish Society and Politics, 1707 to the Present. Taylor&Francis. ISBN 9780203358658. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- "Scottish National Party | History, Policy, & Leader". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- "Will there be another independence referendum?". 25 November 2015. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- The, SNP (7 June 2016), How can the SNP support membership of the EU alongside independence?, archived from the original on 21 March 2021, retrieved 26 October 2020

- Mitchell, James; Bennie, Lynn; Johns, Rob (2012), The Scottish National Party: Transition to Power, Oxford University Press, pp. 107–116

- Keating, Michael (2009), "Nationalist Movements in Comparative Perspective", The Modern SNP: From Protest to Power, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 214–217

- "About Us". Archived from the original on 13 September 2015.

- Eve Hepburn (20 June 2016). New Challenges for Stateless Nationalist and Regionalist Parties. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-96596-1. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Bob Lingard (6 August 2013). Politics, Policies and Pedagogies in Education: The Selected Works of Bob Lingard. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-01998-3. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Massetti, Emanuele (2018), Left‑ wing regionalist populism in the 'Celtic' peripheries: Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party's anti‑austerity challenge against the British elites, Comparative European Politics

- Frans Schrijver (2006). Regionalism After Regionalisation: Spain, France and the United Kingdom. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 261–290. ISBN 978-90-5629-428-1. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2006.

- Lynn Bennie (2017). "The Scottish National Party: Nationalism for the many". In Oscar Mazzoleni; Sean Mueller (eds.). Regionalist Parties in Western Europe: Dimensions of Success. University of Aberdeen. pp. 22–41. ISBN 978-1-317-06895-2. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- "Anti-Brexit feeling expected to help SNP in European elections". The Guardian. 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Hassan, Gerry; Barrow, Simon (1 May 2018). A Nation Changed?: The SNP and Scotland Ten Years on. ISBN 9781910324998. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021. Edited by Gerry Hassan and Simon Barrow. Chapter author – Joyce McMillan. Published in 2017, in Glasgow, Scotland. Published by Bell and Bain Ltd. Retrieved via Google Books.

- "The Scottish National Party Is Embracing A Multicultural Brand Of Nationalism". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- "Mr Scotland, chauvinism and the SNP's big-tent nationalism". Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Josep M. Colomer (July 2008). Political Institutions in Europe. psychology press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-134-07354-2. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Ibpus.com; International Business Publications, USA (1 January 2012). Scotland Business Law Handbook: Strategic Information and Laws. Int'l Business Publications. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4387-7095-6. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Geoff Holder. "10 things you should know about Robert Burns". The History Press. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- Lindsay McIntosh (15 October 2016). "The Scottish parliament is not just a 'blip'". The Times. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- BBC (2016). "Scotland Parliament election 2016". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Local Council Political Compositions". Open Council Date UK. 24 October 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Michael O'Neill (22 May 2014). Devolution and British Politics. Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-317-87365-5. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Gallardo, Cristina (27 November 2019). "Scottish National Party's manifesto explained". Politico. London. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

The SNP wants Scotland to become an independent country and stay in the European Union.

- Mitchell, James; Bennie, Lynn; Johns, Rob (2012), The Scottish National Party: Transition to Power, Oxford University Press, pp. 107–116

- Keating, Michael (2009), "Nationalist Movements in Comparative Perspective", The Modern SNP: From Protest to Power, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 214–217

- Heisey, Monica. "Making the case for an "aye" in Scotland". Alumni Review. Queen's University. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- Carrell, Severin (11 May 2011). "MSPs sworn in at Holyrood after SNP landslide". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- "Open Council Data UK – compositions councillors parties wards elections". opencouncildata.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- "SNP maintains peerage opposition". BBC News. 22 September 2005. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- "House of Lords should be scrapped, says SNP". BBC News. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- Dinwoodie, Robbie (7 April 2014). "From radicals and Tartan Tories to the party of government". The Herald. Glasgow. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Mitchell, James; Hassan, Gerry (2016). Scottish National Party Leaders. London: Biteback. ISBN 978-1-7859-0092-1.

- Wilson, Brian (6 July 2019). "Nationalists quoting Hugh MacDiarmid should read his thoughts on the Nazis". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- Calder, Angus (20 April 2003). "Verse that hit like a bombshell". Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021 – via www.thetimes.co.uk.

- Bowd, Gavin (4 April 2013). Fascist Scotland. ISBN 9780857905680.

- The Newsroom (7 November 2005). "MI5 file links former SNP leader to Nazi plan". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- "Dilemmas of Over-Development: Scottish Nationalism and the Future of the Union". Versobooks.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Faux, Ronald (4 May 1977). "Labour lose control of Glasgow". The Times, p. 1.

- "SNP 11 were the original 'Tartan Tories'". 2 October 2014. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- "SNP MP criticised for defending party's role in bringing Thatcher to power". Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- "The Scottish National Party at 80". BBC News. 11 April 2014. Archived from the original on 12 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- Devine, T. M. (Thomas Martin) (5 July 2012). The Scottish nation : a modern history. London. ISBN 978-0-7181-9673-8. OCLC 1004568536.

- "Ex-MP: Scotland 'in trouble' if lax on constitution – The Targe". thetarge.co.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Former MP Dick Douglas dies aged 82". BBC News. 13 May 2014. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Politics: Anti-bombing Salmond hits an all-time low with voters". The Independent. 13 April 1999. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Britten, Nick (17 July 2000). "Scramble to lead SNP as Salmond quits". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Emphatic SNP win for Swinney". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "McLeish steps down". 8 November 2001. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Our Place in the World: Independence and Scotland's Future". Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "Scottish Independence". Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "Euro poll was breaking point for Swinney". The Scotsman. 23 June 2004. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Salmond named as new SNP leader". 3 September 2004. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "SNP and Greens sign working deal". BBC News Scotland. 11 May 2007. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- Taylor, Brian (23 January 2020). "Could the SNP do a budget deal with the Tories?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "SNP wins majority in Scottish elections". Channel 4. 6 May 2011. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- "Our Party". The SNP. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- "SNP votes to end anti-Nato policy". BBC News. 19 October 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Dailyrecord.co.uk (19 February 2008). "Demand For Alex Salmond Apology Over Kosovo". dailyrecord. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Carrell, Severin; Wintour, Patrick; Mason, Rowena (19 September 2014). "Alex Salmond resigns as first minister after Scotland rejects independence". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "How Scotland voted, and why - Lord Ashcroft Polls". Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- "Scotland's Decision: So Who Voted Yes and Who Voted No?". Centre on Constitutional Change. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- "Election 2015: SNP wins 56 of 59 seats in Scots landslide". BBC News. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- Association, Press (6 May 2017). "Local elections: Sturgeon plays down Tory success in Scotland". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Labour loses control of Glasgow City Council for the first time in 40 years". The Independent. 5 May 2017. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Johnson, Simon; Henderson, Barney (8 June 2017). "Scotland election results: Alex Salmond defeated and SNP suffer huge losses as Tory chances boosted north of the border". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- "General election 2017: SNP lose a third of seats amid Tory surge". BBC News. 9 June 2017. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- Thomas, Natalie; Dickie, Mure (8 June 2017). "Scottish election results strike blow to SNP plans for IndyRef2". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- "General election 2017: SNP lose a third of seats amid Tory surge". BBC. 9 June 2017. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018.

- "SNP wins election landslide in Scotland". BBC News. 13 December 2019. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Scottish Parliament election 2021". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- "SNP-Greens deal pledges indyref2 within five years". BBC News. 20 August 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Sim, Philip (9 May 2022). "The numbers behind Scotland's council election results". BBC News. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- Carrell, Severin (22 September 2014). "SNP poised to become one of UK's largest political parties". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- Morris, Bridget (23 July 2016). "120,000: SNP membership hits record level after post-Brexit surge". The National. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- Gordon, Tom (22 March 2015). "SNP boost as membership soars past 100k mark". The Herald. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- Matchett, Conor (26 August 2021). "SNP spent £615,000 on office refit, annual accounts confirm". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- Peter Lynch (2002). SNP: The History of the Scottish National Party. Welsh Academic Press.

- Jack Brand (1978). The National Movement in Scotland. Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 216–17.

- Jack Brand (1990). 'Scotland', in Watson, Michael (ed.), Contemporary Minority Nationalism. Routledge. p. 28.

- Gerry Hassan (2009). The Modern SNP: From Protest to Power. Edinburgh University Press. p. 120.

- Jack Brand (1990). 'Scotland', in Watson, Michael (ed.), Contemporary Minority Nationalism. Routledge. p. 32.

- James Mitchell (1996). Strategies for Self-government: The Campaigns for a Scottish Parliament. Polygon. p. 208.

- James Mitchell (1996). Strategies for Self-government: The Campaigns for a Scottish Parliament. Polygon. p. 194.

- Jack Brand (1990). 'Scotland', in Watson, Michael (ed.), Contemporary Minority Nationalism. Routledge. p. 27.

- Gerry Hassan (2009). The Modern SNP: From Protest to Power. Edinburgh University Press. p. 121.

- Eve Hepburn (18 October 2013). New Challenges for Stateless Nationalist and Regionalist Parties. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-317-96596-1. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Devenney, Andrew D. (2008). "Regional Resistance to European Integration: The Case of the Scottish National Party, 1961–1972". Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung. 33 (3 (125)): 319–345. ISSN 0172-6404. JSTOR 20762312.

- Ley, Shaun (18 August 2016). "The dilemma facing Scotland's Eurosceptic nationalists". Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Scottish income tax changes unveiled". BBC News. 14 December 2017. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "New property tax comes into effect". BBC News. 1 April 2015. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Carrell, Severin; correspondent, Scotland (11 February 2009). "Alex Salmond drops flat-rate local income tax plan". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Nicola Sturgeon confirms end to council tax freeze as those living in more expensive homes face higher bills". Holyrood Website. 3 October 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "MSPs vote to raise council tax bands". BBC News. 3 November 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Scottish business rate reforms confirmed". BBC News. 12 September 2017. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Millar, James (16 March 2017). "5 of the biggest splits behind the SNP's disciplined facade". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- Millar, James (13 October 2016). "The SNP can't mask its left-right split forever". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- Robin Cook (22 July 1980). "Homosexual Offences". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 286.

- "Homosexual Offences". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. 22 July 1980. col. 321.

- "Scotland tops Europe for LGBTI equality and human rights". The Scotsman. 10 May 2016. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- MacNicol, David (27 July 2017). "Illegal to be gay – Scotland's history". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "The tartan rainbow: Why it's great to be gay in Scotland". TheGuardian.com. 5 April 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "The Scottish government just confirmed the next step for the reformation of the Gender Recognition Act". PinkNews. 3 September 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Farquharson, Kenny. "Wings Over Scotland independence blogger Stuart Campbell plans to take on SNP". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Several women 'close to quitting SNP over gender recognition plans'". The Guardian. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- "Joanna Cherry accuses SNP colleagues of 'performative histrionics' over transgender issue". The Independent. 10 February 2021. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- Wade, Mike. "Anger over trans woman on all-female SNP shortlist". Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021 – via www.thetimes.co.uk.

- Sanderson, Daniel (1 February 2021). "SNP civil war deepens as leading Sturgeon critic Joanna Cherry purged from Westminster team". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- "Why has the SNP been accused of 'transphobic views' - and who is Teddy Hope?". www.scotsman.com. February 2021. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- "Nicola Sturgeon says transphobia in SNP 'not acceptable'". BBC News. 28 January 2021. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- "Nicola Sturgeon: transphobia in SNP is 'not acceptable' – video". The Guardian. 28 January 2021. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021 – via www.theguardian.com.

- Brooks, Libby (21 November 2014). "Nicola Sturgeon announces Scottish cabinet with equal gender balance". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Webster, Catriona. "Nicola Sturgeon marks International Women's day by launching search for new woman to mentor". The Sunday Post. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "The SNP are right to adopt all women shortlists". Bella Caledonia. 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "The Scottish National Party Is Espousing A Multicultural Brand of Nationalism". NPR.org. NPR. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Fifth of UK's Syrian refugees in Scotland". BBC News. 16 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Syrian refugees in Scotland 'much happier' than those in England". The Scotsman. 26 July 2018. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "SNP demand immigration powers as population growth stutters". The Herald. Glasgow. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2020.