Wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids.[1] The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As an animal fibre, wool consists of protein together with a small percentage of lipids. This makes it chemically quite distinct from cotton and other plant fibres, which are mainly cellulose.[1]

Characteristics

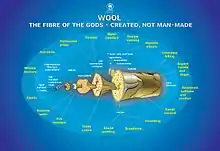

Wool is produced by follicles which are small cells located in the skin. These follicles are located in the upper layer of the skin called the epidermis and push down into the second skin layer called the dermis as the wool fibers grow. Follicles can be classed as either primary or secondary follicles. Primary follicles produce three types of fiber: kemp, medullated fibers, and true wool fibers. Secondary follicles only produce true wool fibers. Medullated fibers share nearly identical characteristics to hair and are long but lack crimp and elasticity. Kemp fibers are very coarse and shed out.[2]

Wool's crimp refers to the strong natural wave present in each wool fibre as it in presented on the animal. Wool's crimp, and to a lesser degree scales, make it easier to spin the fleece by helping the individual fibers attach to each other, so they stay together. Because of the crimp, wool fabrics have greater bulk than other textiles, and they hold air, which causes the fabric to retain heat. Wool has a high specific thermal resistance, so it impedes heat transfer in general. This effect has benefited desert peoples, as Bedouins and Tuaregs use wool clothes for insulation.

Felting of wool occurs upon hammering or other mechanical agitation as the microscopic barbs on the surface of wool fibers hook together. Felting generally comes under two main areas, dry felting or wet felting. Wet felting occurs when water and a lubricant (especially an alkali such as soap) are applied to the wool which is then agitated until the fibers mix and bond together. Temperature shock while damp or wet accentuates the felting process. Some natural felting can occur on the animals back.

Wool has several qualities that distinguish it from hair or fur: it is crimped and elastic.[3]

The amount of crimp corresponds to the fineness of the wool fibers. A fine wool like Merino may have up to 40 crimps per centimetre (100 crimps per inch), while coarser wool like karakul may have less than one (one or two crimps per inch). In contrast, hair has little if any scale and no crimp, and little ability to bind into yarn. On sheep, the hair part of the fleece is called kemp. The relative amounts of kemp to wool vary from breed to breed and make some fleeces more desirable for spinning, felting, or carding into batts for quilts or other insulating products, including the famous tweed cloth of Scotland.

Wool fibers readily absorb moisture, but are not hollow. Wool can absorb almost one-third of its own weight in water.[4] Wool absorbs sound like many other fabrics. It is generally a creamy white color, although some breeds of sheep produce natural colors, such as black, brown, silver, and random mixes.

Wool ignites at a higher temperature than cotton and some synthetic fibers. It has a lower rate of flame spread, a lower rate of heat release, a lower heat of combustion, and does not melt or drip;[5] it forms a char that is insulating and self-extinguishing, and it contributes less to toxic gases and smoke than other flooring products when used in carpets.[6] Wool carpets are specified for high safety environments, such as trains and aircraft. Wool is usually specified for garments for firefighters, soldiers, and others in occupations where they are exposed to the likelihood of fire.[6]

Wool causes an allergic reaction in some people.[7]

Processing

Shearing

Sheep shearing is the process in which a worker (a shearer) cuts off the woolen fleece of a sheep. After shearing, wool-classers separate the wool into four main categories:

- fleece (which makes up the vast bulk)

- broken

- bellies

- locks

The quality of fleeces is determined by a technique known as wool classing, whereby a qualified person, called a wool classer, groups wools of similar grading together to maximize the return for the farmer or sheep owner. In Australia, before being auctioned, all Merino fleece wool is objectively measured for average diameter (micron), yield (including the amount of vegetable matter), staple length, staple strength, and sometimes color and comfort factor.

Scouring

Wool straight off a sheep is known as "raw wool”, “greasy wool"[8] or "wool in the grease". This wool contains a high level of valuable lanolin, as well as the sheep's dead skin and sweat residue, and generally also contains pesticides and vegetable matter from the animal's environment. Before the wool can be used for commercial purposes, it must be scoured, a process of cleaning the greasy wool. Scouring may be as simple as a bath in warm water or as complicated as an industrial process using detergent and alkali in specialized equipment.[9] In north west England, special potash pits were constructed to produce potash used in the manufacture of a soft soap for scouring locally produced white wool.

Vegetable matter in commercial wool is often removed by chemical carbonization.[10] In less-processed wools, vegetable matter may be removed by hand and some of the lanolin left intact through the use of gentler detergents. This semigrease wool can be worked into yarn and knitted into particularly water-resistant mittens or sweaters, such as those of the Aran Island fishermen. Lanolin removed from wool is widely used in cosmetic products such as hand creams.

Fineness and yield

Raw wool has many impurities; vegetable matter, sand, dirt and yolk which is a mixture of suint (sweat), grease, urine stains and dung locks. The sheep's body yields many types of wool with differing strengths, thicknesses, length of staple and impurities. The raw wool (greasy) is processed into 'top'. 'Worsted top' requires strong straight and parallel fibres.

| Common Name | Part of Sheep | Style of Wool |

|---|---|---|

| Fine | Shoulder | Fine, uniform and very dense |

| Near | Sides | Fine, uniform and strong |

| Downrights | Neck | Short and irregular, lower quality |

| Choice | Back | Shorter staple, open and less strong |

| Abb | Haunches | Longer, stronger staple |

| Seconds | Belly | Short, tender, matted and dirty |

| Top-not | Head | Stiff, very coarse, rough and kempy |

| Brokes | Forelegs | Short, irregular and faulty |

| Cowtail | Hindlegs | Very strong, coarse and hairy |

| Britch | Tail | Very coarse, kempy and dirty |

| Source:[11] | ||

The quality of wool is determined by its fiber diameter, crimp, yield, color, and staple strength. Fiber diameter is the single most important wool characteristic determining quality and price.

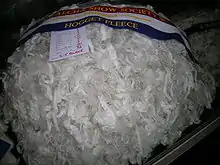

Merino wool is typically 90–115 mm (3.5–4.5 in) in length and is very fine (between 12 and 24 microns).[12] The finest and most valuable wool comes from Merino hoggets. Wool taken from sheep produced for meat is typically coarser, and has fibers 40–150 mm (1.5–6 in) in length. Damage or breaks in the wool can occur if the sheep is stressed while it is growing its fleece, resulting in a thin spot where the fleece is likely to break.[13]

Wool is also separated into grades based on the measurement of the wool's diameter in microns and also its style. These grades may vary depending on the breed or purpose of the wool. For example:

| Diameter in microns | Name |

|---|---|

| < 15.5 | Ultrafine Merino[8] |

| 15.6–18.5 | Superfine Merino |

| 18.6–20 | Fine Merino[8] |

| 20.1–23 | Medium Merino |

| > 23 | Strong Merino[8] |

| Breeds | Diameter |

|---|---|

| Comeback | 21–26 microns, white, 90–180 mm (3.5–7.1 in) long |

| Fine crossbred | 27–31 microns, Corriedales, etc. |

| Medium crossbred | 32–35 microns |

| Downs | 23–34 microns, typically lacks luster and brightness. Examples, Aussiedown, Dorset Horn, Suffolk, etc.[14] |

| Coarse crossbred | >36 microns |

| Carpet wools | 35–45 microns[8] |

Any wool finer than 25 microns can be used for garments, while coarser grades are used for outerwear or rugs. The finer the wool, the softer it is, while coarser grades are more durable and less prone to pilling.

The finest Australian and New Zealand Merino wools are known as 1PP, which is the industry benchmark of excellence for Merino wool 16.9 microns and finer. This style represents the top level of fineness, character, color, and style as determined on the basis of a series of parameters in accordance with the original dictates of British wool as applied by the Australian Wool Exchange (AWEX) Council. Only a few dozen of the millions of bales auctioned every year can be classified and marked 1PP.[15]

In the United States, three classifications of wool are named in the Wool Products Labeling Act of 1939.[16] Wool is "the fiber from the fleece of the sheep or lamb or hair of the Angora or Cashmere goat (and may include the so-called specialty fibers from the hair of the camel, alpaca, llama, and vicuna) which has never been reclaimed from any woven or felted wool product".[16] "Virgin wool" and "new wool" are also used to refer to such never used wool. There are two categories of recycled wool (also called reclaimed or shoddy wool). "Reprocessed wool" identifies "wool which has been woven or felted into a wool product and subsequently reduced to a fibrous state without having been used by the ultimate consumer".[16] "Reused wool" refers to such wool that has been used by the ultimate consumer.[16]

History

Wild sheep were more hairy than woolly. Although sheep were domesticated some 9,000 to 11,000 years ago, archaeological evidence from statuary found at sites in Iran suggests selection for woolly sheep may have begun around 6000 BC,[17][18] with the earliest woven wool garments having only been dated to two to three thousand years later.[19] Woolly sheep were introduced into Europe from the Near East in the early part of the 4th millennium BC. The oldest known European wool textile, ca. 1500 BC, was preserved in a Danish bog.[20] Prior to invention of shears—probably in the Iron Age—the wool was plucked out by hand or by bronze combs. In Roman times, wool, linen, and leather clothed the European population; cotton from India was a curiosity of which only naturalists had heard, and silks, imported along the Silk Road from China, were extravagant luxury goods. Pliny the Elder records in his Natural History that the reputation for producing the finest wool was enjoyed by Tarentum, where selective breeding had produced sheep with superior fleeces, but which required special care.

In medieval times, as trade connections expanded, the Champagne fairs revolved around the production of wool cloth in small centers such as Provins. The network developed by the annual fairs meant the woolens of Provins might find their way to Naples, Sicily, Cyprus, Majorca, Spain, and even Constantinople.[21] The wool trade developed into serious business, a generator of capital.[22] In the 13th century, the wool trade became the economic engine of the Low Countries and central Italy. By the end of the 14th century, Italy predominated.[21] The Florentine wool guild, Arte della Lana, sent the imported English wool to the San Martino convent for processing. Italian wool from Abruzzo and Spanish merino wools were processed at Garbo workshops. Abruzzo wool had once been the most accessible for the Florentine guild, until improved relations with merchants in Iberia made merino wool more available. By the 16th century Italian wool exports to the Levant had declined, eventually replaced by silk production.[21][23]

Both industries, based on the export of English raw wool, were rivaled only by the 15th-century sheepwalks of Castile and were a significant source of income to the English crown, which in 1275 had imposed an export tax on wool called the "Great Custom". The importance of wool to the English economy can be seen in the fact that since the 14th century, the presiding officer of the House of Lords has sat on the "Woolsack", a chair stuffed with wool.

Economies of scale were instituted in the Cistercian houses, which had accumulated great tracts of land during the 12th and early 13th centuries, when land prices were low and labor still scarce. Raw wool was baled and shipped from North Sea ports to the textile cities of Flanders, notably Ypres and Ghent, where it was dyed and worked up as cloth. At the time of the Black Death, English textile industries accounted for about 10% of English wool production. The English textile trade grew during the 15th century, to the point where export of wool was discouraged. Over the centuries, various British laws controlled the wool trade or required the use of wool even in burials. The smuggling of wool out of the country, known as owling, was at one time punishable by the cutting off of a hand. After the Restoration, fine English woolens began to compete with silks in the international market, partly aided by the Navigation Acts; in 1699, the English crown forbade its American colonies to trade wool with anyone but England herself.

A great deal of the value of woolen textiles was in the dyeing and finishing of the woven product. In each of the centers of the textile trade, the manufacturing process came to be subdivided into a collection of trades, overseen by an entrepreneur in a system called by the English the "putting-out" system, or "cottage industry", and the Verlagssystem by the Germans. In this system of producing wool cloth, once perpetuated in the production of Harris tweeds, the entrepreneur provides the raw materials and an advance, the remainder being paid upon delivery of the product. Written contracts bound the artisans to specified terms. Fernand Braudel traces the appearance of the system in the 13th-century economic boom, quoting a document of 1275.[21] The system effectively bypassed the guilds' restrictions.

Before the flowering of the Renaissance, the Medici and other great banking houses of Florence had built their wealth and banking system on their textile industry based on wool, overseen by the Arte della Lana, the wool guild: wool textile interests guided Florentine policies. Francesco Datini, the "merchant of Prato", established in 1383 an Arte della Lana for that small Tuscan city. The sheepwalks of Castile were controlled by the Mesta union of sheep owners. They shaped the landscape and the fortunes of the meseta that lies in the heart of the Iberian peninsula; in the 16th century, a unified Spain allowed export of Merino lambs only with royal permission. The German wool market – based on sheep of Spanish origin – did not overtake British wool until comparatively late. The Industrial Revolution introduced mass production technology into wool and wool cloth manufacturing. Australia's colonial economy was based on sheep raising, and the Australian wool trade eventually overtook that of the Germans by 1845, furnishing wool for Bradford, which developed as the heart of industrialized woolens production.

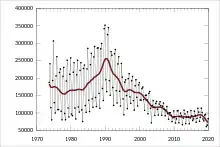

Due to decreasing demand with increased use of synthetic fibers, wool production is much less than what it was in the past. The collapse in the price of wool began in late 1966 with a 40% drop; with occasional interruptions, the price has tended down. The result has been sharply reduced production and movement of resources into production of other commodities, in the case of sheep growers, to production of meat.[24][25][26]

Superwash wool (or washable wool) technology first appeared in the early 1970s to produce wool that has been specially treated so it is machine washable and may be tumble-dried. This wool is produced using an acid bath that removes the "scales" from the fiber, or by coating the fiber with a polymer that prevents the scales from attaching to each other and causing shrinkage. This process results in a fiber that holds longevity and durability over synthetic materials, while retaining its shape.[27]

In December 2004, a bale of the then world's finest wool, averaging 11.8 microns, sold for AU$3,000 per kilogram at auction in Melbourne. This fleece wool tested with an average yield of 74.5%, 68 mm (2.7 in) long, and had 40 newtons per kilotex strength. The result was A$279,000 for the bale.[28] The finest bale of wool ever auctioned was sold for a seasonal record of AU$2690 per kilo during June 2008. This bale was produced by the Hillcreston Pinehill Partnership and measured 11.6 microns, 72.1% yield, and had a 43 newtons per kilotex strength measurement. The bale realized $247,480 and was exported to India.[29]

In 2007, a new wool suit was developed and sold in Japan that can be washed in the shower, and which dries off ready to wear within hours with no ironing required. The suit was developed using Australian Merino wool, and it enables woven products made from wool, such as suits, trousers, and skirts, to be cleaned using a domestic shower at home.[30]

In December 2006, the General Assembly of the United Nations proclaimed 2009 to be the International Year of Natural Fibres, so as to raise the profile of wool and other natural fibers.

Production

Global wool production is about 2 million tonnes (2.2 million short tons) per year, of which 60% goes into apparel. Wool comprises ca 3% of the global textile market, but its value is higher owing to dyeing and other modifications of the material.[1] Australia is a leading producer of wool which is mostly from Merino sheep but has been eclipsed by China in terms of total weight.[31] New Zealand (2016) is the third-largest producer of wool, and the largest producer of crossbred wool. Breeds such as Lincoln, Romney, Drysdale, and Elliotdale produce coarser fibers, and wool from these sheep is usually used for making carpets.

In the United States, Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado have large commercial sheep flocks and their mainstay is the Rambouillet (or French Merino). Also, a thriving home-flock contingent of small-scale farmers raise small hobby flocks of specialty sheep for the hand-spinning market. These small-scale farmers offer a wide selection of fleece. Global woolclip (total amount of wool shorn) 2020[32]

- China: 19% of global wool-clip (334 million kilograms [740 million pounds] greasy, 2020)

- Australia: 16%

- New Zealand: 8%

- Turkey: 4%

- United Kingdom: 4%

- Morocco: 3%

- Iran: 3%

- Russia: 3%

- South Africa: 3%

- India: 3%

Organic wool has gained in popularity. This wool is limited in supply and much of it comes from New Zealand and Australia.[33] Organic wool has become easier to find in clothing and other products, but these products often carry a higher price. Wool is environmentally preferable (as compared to petroleum-based nylon or polypropylene) as a material for carpets, as well, in particular when combined with a natural binding and the use of formaldehyde-free glues.

Animal rights groups have noted issues with the production of wool, such as mulesing.

Marketing

Australia

About 85% of wool sold in Australia is sold by open cry auction.[34]

Other countries

The British Wool Marketing Board operates a central marketing system for UK fleece wool with the aim of achieving the best possible net returns for farmers.

Less than half of New Zealand's wool is sold at auction, while around 45% of farmers sell wool directly to private buyers and end-users.[35]

United States sheep producers market wool with private or cooperative wool warehouses, but wool pools are common in many states. In some cases, wool is pooled in a local market area, but sold through a wool warehouse. Wool offered with objective measurement test results is preferred. Imported apparel wool and carpet wool goes directly to central markets, where it is handled by the large merchants and manufacturers.[36]

Yarn

Shoddy or recycled wool is made by cutting or tearing apart existing wool fabric and respinning the resulting fibers.[37] As this process makes the wool fibers shorter, the remanufactured fabric is inferior to the original. The recycled wool may be mixed with raw wool, wool noil, or another fiber such as cotton to increase the average fiber length. Such yarns are typically used as weft yarns with a cotton warp. This process was invented in the Heavy Woollen District of West Yorkshire and created a microeconomy in this area for many years.

Worsted is a strong, long-staple, combed wool yarn with a hard surface.[37]

Woolen is a soft, short-staple, carded wool yarn typically used for knitting.[37] In traditional weaving, woolen weft yarn (for softness and warmth) is frequently combined with a worsted warp yarn for strength on the loom.[38]

Uses

In addition to clothing, wool has been used for blankets, horse rugs, saddle cloths, carpeting, insulation and upholstery. Wool felt covers piano hammers, and it is used to absorb odors and noise in heavy machinery and stereo speakers. Ancient Greeks lined their helmets with felt, and Roman legionnaires used breastplates made of wool felt.

Wool as well as cotton has also been traditionally used for cloth diapers.[39] Wool fiber exteriors are hydrophobic (repel water) and the interior of the wool fiber is hygroscopic (attracts water); this makes a wool garment suitable cover for a wet diaper by inhibiting wicking, so outer garments remain dry. Wool felted and treated with lanolin is water resistant, air permeable, and slightly antibacterial, so it resists the buildup of odor. Some modern cloth diapers use felted wool fabric for covers, and there are several modern commercial knitting patterns for wool diaper covers.

Initial studies of woolen underwear have found it prevented heat and sweat rashes because it more readily absorbs the moisture than other fibers.[40]

As an animal protein, wool can be used as a soil fertilizer, being a slow-release source of nitrogen.

Researchers at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology school of fashion and textiles have discovered a blend of wool and Kevlar, the synthetic fiber widely used in body armor, was lighter, cheaper and worked better in damp conditions than Kevlar alone. Kevlar, when used alone, loses about 20% of its effectiveness when wet, so required an expensive waterproofing process. Wool increased friction in a vest with 28–30 layers of fabric, to provide the same level of bullet resistance as 36 layers of Kevlar alone.[41]

Events

A buyer of Merino wool, Ermenegildo Zegna, has offered awards for Australian wool producers. In 1963, the first Ermenegildo Zegna Perpetual Trophy was presented in Tasmania for growers of "Superfine skirted Merino fleece". In 1980, a national award, the Ermenegildo Zegna Trophy for Extrafine Wool Production, was launched. In 2004, this award became known as the Ermenegildo Zegna Unprotected Wool Trophy. In 1998, an Ermenegildo Zegna Protected Wool Trophy was launched for fleece from sheep coated for around nine months of the year.

In 2002, the Ermenegildo Zegna Vellus Aureum Trophy was launched for wool that is 13.9 microns or finer. Wool from Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, and South Africa may enter, and a winner is named from each country.[42] In April 2008, New Zealand won the Ermenegildo Zegna Vellus Aureum Trophy for the first time with a fleece that measured 10.8 microns. This contest awards the winning fleece weight with the same weight in gold as a prize, hence the name.

In 2010, an ultrafine, 10-micron fleece, from Windradeen, near Pyramul, New South Wales, won the Ermenegildo Zegna Vellus Aureum International Trophy.[43]

Since 2000, Loro Piana has awarded a cup for the world's finest bale of wool that produces just enough fabric for 50 tailor-made suits. The prize is awarded to an Australian or New Zealand wool grower who produces the year's finest bale.[44]

The New England Merino Field days which display local studs, wool, and sheep are held during January, in even numbered years around the Walcha, New South Wales district. The Annual Wool Fashion Awards, which showcase the use of Merino wool by fashion designers, are hosted by the city of Armidale, New South Wales, in March each year. This event encourages young and established fashion designers to display their talents. During each May, Armidale hosts the annual New England Wool Expo to display wool fashions, handicrafts, demonstrations, shearing competitions, yard dog trials, and more.[1]

In July, the annual Australian Sheep and Wool Show is held in Bendigo, Victoria. This is the largest sheep and wool show in the world, with goats and alpacas, as well as woolcraft competitions and displays, fleece competitions, sheepdog trials, shearing, and wool handling. The largest competition in the world for objectively measured fleeces is the Australian Fleece Competition, which is held annually at Bendigo. In 2008, 475 entries came from all states of Australia, with first and second prizes going to the Northern Tablelands, New South Wales fleeces.[45]

See also

- Timeline of clothing and textiles technology

Production

- Glossary of sheep husbandry

- Lambswool

- Sheep husbandry

- Sheep shearing

- Wool bale

Processing

- Canvas work

- Carding

- Combing

- Dyeing

- Fulling

- Knitting

- Spinning

- Textile manufacturing

- Weaving

Organizations

- British Wool Marketing Board

- IWTO

- Worshipful Company of Woolmen

Miscellaneous wool

- Alpaca wool

- Angora wool

- Cashmere wool

- Chiengora wool

- Glass wool

- Llama wool

- Lopi

- Mineral wool

- Mohair

- Pashmina

- Shahtoosh

- Tibetan fur

References

- Braaten, Ann W. (2005). "Wool". In Steele, Valerie (ed.). Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion. Vol. 3. Thomson Gale. pp. 441–443. ISBN 0-684-31394-4.

- Simmons, Paula (2009). Storey's Guide to Raising Sheep. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing. pp. 315–316.

- D'Arcy, John B. (1986). Sheep and Wool Technology. Kensington: NSW University Press. ISBN 0-86840-106-4.

- Wool Facts Archived 2014-05-26 at the Wayback Machine. Aussiesheepandwool.com.au. Retrieved on 2012-08-05.

- Wool History Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine. Tricountyfarm.org. Retrieved on 2012-08-05.

- The Land, Merinos – Going for Green and Gold, p.46, US use flame resistance, 21 August 2008

- Admani, Shehla; Jacob, Sharon E. (2014-04-01). "Allergic contact dermatitis in children: review of the past decade". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 14 (4): 421. doi:10.1007/s11882-014-0421-0. PMID 24504525. S2CID 33537360.

- Preparation of Australian Wool Clips, Code of Practice 2010–2012, Australian Wool Exchange (AWEX), 2010

- "Technology in Australia 1788–1988". Australian Science and Technology Heritage Center. 2001. Archived from the original on 2006-05-14. Retrieved 2006-04-30.

- Wu Zhao (1987). A study of wool carbonizing (PhD). University of New South Wales. School of Fibre Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 30 October 2014.

- Bradford Industrial Museum 2015.

- "Merino Sheep in Australia". Archived from the original on 2006-11-05. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- Van Nostran, Don. "Wool Management – Maximizing Wool Returns". Mid-States Wool growers Cooperative Association. Archived from the original on 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- D'Arcy, John B. (1986). Sheep Management & Wool Technology. NSW University Press. ISBN 0-86840-106-4.

- 1PP Certification. awex.com.au

- Robert E. Freer. "The Wool Products Labeling Act of 1939." Archived 2016-06-05 at the Wayback Machine Temple Law Quarterly. 20.1 (July 1946). p. 47. Reprinted at ftc.gov. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Ensminger, M. E.; R. O. Parker (1986). Sheep and Goat Science, Fifth Edition. Danville, Illinois: The Interstate Printers and Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-8134-2464-X.

- Weaver, Sue (2005). Sheep: small-scale sheep keeping for pleasure and profit. Irvine, CA: Hobby Farm Press, an imprint of BowTie Press, a division of BowTie Inc. ISBN 1-931993-49-1.

- Smith, Barbara; Kennedy, Gerald; Aseltine, Mark (1997). Beginning Shepherd's Manual, Second Edition. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press. ISBN 0-8138-2799-X.

- "Fibre history". Woolmark. Archived from the original on 2006-08-28.

- Fernand Braudel, 1982. The Wheels of Commerce, vol 2 of Civilization and Capitalism (New York:Harper & Row), pp.312–317

- Bell, Adrian R.; Brooks, Chris; Dryburgh, Paul (2007). The English Wool Market, c.1230–1327. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521859417.

- "Florentine Woolen Manufacture in the Sixteenth Century:Crisis and New Entrepreneurial Strategies" (PDF). THe Business History Conference.

- "The end of pastoral dominance" Archived 2007-08-19 at the Wayback Machine. Teara.govt.nz (2009-03-03). Retrieved on 2012-08-05.

- 1301.0 – Year Book Australia, 2000 Archived 2017-07-01 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Bureau of Statistics

- "The History of Wool" Archived 2015-04-27 at the Wayback Machine. johnhanly.com

- Superwash Wool Archived 2009-03-09 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 10 November 2008

- World’s Finest Bale Record Broken. landmark.com.au, 22 November 2004

- Country Leader, NSW Wool Sells for a Quarter of a Million, 7 July 2008

- Shower suit Archived 2011-08-22 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 11 November 2008

- "Sheep 101". Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016. According to this chart, US production is around 10,000 tonnes (11,000 short tons), hugely at variance with the percentage list, and way outside year-to-year variability.

- "FAOSTAT". Food And Agriculture Organization Of The United Nations. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- Speer, Jordan K. (2006-05-01). "Shearing the Edge of Innovation". Apparel Magazine. Archived from the original on 2015-05-26.

- Bolt, C (2004-04-07). "AWH to set up wool auctions". The Age. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Wool Production in New Zealand. maf.govt.nz

- Wool Marketing. sheepusa.org

- Kadolph, Sara J, ed. (2007). Textiles (10 ed.). Pearson/Prentice-Hall. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-13-118769-6.

- Østergård, Else (2004). Woven into the Earth: Textiles from Norse Greenland. Aarhus University Press. p. 50. ISBN 87-7288-935-7.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2015). World Clothing and Fashion : an Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Social Influence. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-1-317-45167-9. OCLC 910448387.

- ABC Rural Radio: Woodhams, Dr. Libby, New research shows woollen underwear helps prevent rashes Archived 2011-08-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-3-24

- Blenkin, Max (2011-04-11). "Wool's tough new image". Country Leader.

- "2004/51/1 Trophy and plaque, Ermenegildo Zegna Vellus Aureum trophy and plaque, plaster / bronze / silver / gold, trophy designed and made by Not Vital for Ermenegildo Zegna, Switzerland, 2001". Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Archived from the original on 2007-05-19. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- Country Leader, 26 April 2010, Finest wool rewarded, Rural Press, North Richmond

- Australian Wool Network News, Issue #19, July 2008

- "Fletcher Wins Australian Fleece Comp". Walcha News. 24 July 2008. p. 3. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

External links

- . . 1914.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

.svg.png.webp)