Sea of Galilee

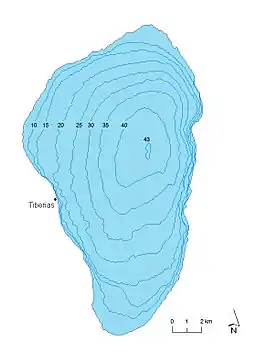

The Sea of Galilee (Hebrew: יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, Arabic: بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth,[3] is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest freshwater lake on Earth and the second-lowest lake in the world (after the Dead Sea, a saltwater lake),[4] at levels between 215 metres (705 ft) and 209 metres (686 ft) below sea level.[5] It is approximately 53 km (33 mi) in circumference, about 21 km (13 mi) long, and 13 km (8.1 mi) wide. Its area is 166.7 km2 (64.4 sq mi) at its fullest, and its maximum depth is approximately 43 metres (141 ft).[6] The lake is fed partly by underground springs, but its main source is the Jordan River, which flows through it from north to south and exits the lake at the Degania Dam.

| Sea of Galilee – Kinneret | |

|---|---|

| |

Sea of Galilee – Kinneret  Sea of Galilee – Kinneret | |

| |

| Coordinates | 32°50′N 35°35′E |

| Lake type | Monomictic |

| Primary inflows | Upper Jordan River and local runoff[1] |

| Primary outflows | Lower Jordan River, evaporation |

| Catchment area | 2,730 km2 (1,050 sq mi)[2] |

| Basin countries | Israel, Syria, Lebanon |

| Max. length | 21 km (13 mi) |

| Max. width | 13 km (8.1 mi) |

| Surface area | 166 km2 (64 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 25.6 m (84 ft) (varying) |

| Max. depth | 43 m (141 ft) (varying) |

| Water volume | 4 km3 (0.96 cu mi) |

| Residence time | 5 years |

| Shore length1 | 53 km (33 mi) |

| Surface elevation | −214.66 m (704.3 ft) (varying) |

| Settlements | Tiberias (Israel) |

| References | [1][2] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Geography

The Sea of Galilee is situated in northeast Israel, between the Golan Heights and the Galilee region, in the Jordan Rift Valley, the valley caused by the separation of the African and Arabian plates. Consequently, the area is subject to earthquakes, and in the past, volcanic activity. This is evident from the abundant basalt and other igneous rocks that define the geology of Galilee.

Names

The lake has been called by different names throughout its history, usually depending on the dominant settlement on its shores. With the changing fate of the towns, the lake's name also changed.

Sea of Kinneret

The modern Hebrew name, Kinneret, comes from the Hebrew Bible where it appears as the "sea of Kinneret" in Numbers 34:11 and Joshua 13:27, spelled כנרות "Kinnerot" in Hebrew in Joshua 11:2. This name was also found in the scripts of Ugarit, in the Aqhat Epic. As the name of a city, Kinneret was listed among the "fenced cities" in Joshua 19:35. A persistent, though likely erroneous, popular etymology of the name presumes that the name Kinneret may originate from the Hebrew word kinnor ("harp" or "lyre"), because of the shape of the lake.[7] The scholarly consensus, however, is that the origin of the name is derived from the important Bronze and Iron Age city of Kinneret, excavated at Tell el-'Oreimeh.[8] The city of Kinneret may have been named after the body of water rather than vice versa, and there is no evidence for the origin of the town's name. For a different etymology, see Galilee#Sea of Galilee.

Lake of Gennesaret

All Old and New Testament writers use the term "sea" (Hebrew יָם yam, Greek θάλασσα), with the exception of Luke, who calls it "the Lake of Gennesaret" (Luke 5:1), from the Greek λίμνη Γεννησαρέτ (limnē Gennēsaret), the "Grecized form of Chinnereth" according to Easton (1897).[9] For a different etymology, see Galilee#Sea of Galilee.

Sea of Ginosar

The Babylonian Talmud, as well as Flavius Josephus, mention the sea by the name "Sea of Ginosar" after the small fertile plain of Ginosar that lies on its western side.[10] Ginosar is yet another name derived from "Kinneret".[8]

Sea of Galilee, Sea of Tiberias, Lake Tiberias

The word "Galilee" comes from the Hebrew Haggalil (הַגָלִיל), which literally means "The District", a compressed form of Gelil Haggoyim "The District of Nations" (Isaiah 8:23).

Toward the end of the first century CE, the Sea of Galilee became widely known as the Sea of Tiberias after the eponymous city founded on its western shore in honour of the second Roman emperor, Tiberius.

In the New Testament, the term "sea of Galilee" (Greek: θάλασσαν τῆς Γαλιλαίας, thalassan tēs Galilaias) is used in the gospel of Matthew 4:18; 15:29, the gospel of Mark 1:16; 7:31, and in the gospel of John 6:1 as "the sea of Galilee, which is the sea of Tiberias" (θαλάσσης τῆς Γαλιλαίας τῆς Τιβεριάδος, thalassēs tēs Galilaias tēs Tiberiados), the late 1st century CE name.[11] Sea of Tiberias is also the name mentioned in Roman texts and in the Jerusalem Talmud, and it was adopted into Arabic as ![]() Buḥayret Ṭabariyyā (بحيرة طبريا), "Lake Tiberias".

Buḥayret Ṭabariyyā (بحيرة طبريا), "Lake Tiberias".

Sea of Minya

From the Umayyad through the Mamluk period, the lake was known in Arabic as "Bahr al-Minya", the "Sea of Minya", after the Umayyad qasr complex, whose ruins are still visible at Khirbat al-Minya. This is the name used by the medieval Persian and Arab scholars Al-Baladhuri, Al-Tabari and Ibn Kathir.[12]

History

Prehistory

In 1989, remains of a hunter-gatherer site were found under the water at the southern end. Remains of mud huts were found in Ohalo. Nahal Ein Gev, located about 3 km east of the lake, contains a village from the late Natufian period. The site is considered one of the first permanent human settlements in the world from a time predating the Neolithic revolution.[13]

Hellenistic and Roman periods

The Sea of Galilee lies on the ancient Via Maris, which linked Egypt with the northern empires. The Greeks, Hasmoneans, and Romans founded flourishing towns and settlements on the lake including Hippos and Tiberias. The first-century historian Flavius Josephus was so impressed by the area that he wrote, "One may call this place the ambition of Nature"; he also reported a thriving fishing industry at this time, with 230 boats regularly working in the lake. Archaeologists discovered one such boat, nicknamed the Jesus Boat, in 1986.

The New Testament

_-_James_Tissot.jpg.webp)

In the New Testament, much of the ministry of Jesus occurs on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. In those days, there was a continuous ribbon development of settlements and villages around the lake and plenty of trade and ferrying by boat. The Synoptic Gospels of Mark 1:14–20), Matthew 4:18–22), and Luke 5:1–11) describe how Jesus recruited four of his apostles from the shores of the Kinneret: the fishermen Simon and his brother Andrew and the brothers John and James. One of Jesus' famous teaching episodes, the Sermon on the Mount, is supposed to have been given on a hill overlooking the Kinneret. Many of his miracles are also said to have occurred here including his walking on water, calming the storm, the disciples and the miraculous catch of fish, and his feeding five thousand people (in Tabgha). In John's Gospel the sea provides the setting for Jesus' third post-resurrection appearance to his disciples (John 21).

Late Roman period

In 135 CE, Bar Kokhba's revolt was put down. The Romans responded by banning all Jews from Jerusalem. The center of Jewish culture and learning shifted to the region of Galilee and the Kinneret, particularly the city of Tiberias. It was in this region that the Jerusalem Talmud was compiled.

Byzantine period

In the time of the Byzantine Empire, the Kinneret's significance in Jesus' life made it a major destination for Christian pilgrims. This led to the growth of a full-fledged tourist industry, complete with package tours and plenty of comfortable inns.

Early Muslim and Crusader periods

The Sea of Galilee's importance declined when the Byzantines lost control and the area was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate and subsequent Islamic empires. The palace of Minya was built by the lake during the reign of the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I (705–715 CE). Apart from Tiberias, the major towns and cities in the area were gradually abandoned.

In 1187, Sultan Saladin defeated the armies of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem at the Battle of Hattin, largely because he was able to cut the Crusaders off from the valuable fresh water of the Sea of Galilee.

Ottoman period

The lake had little importance within the early Ottoman Empire. Tiberias did see a significant revival of its Jewish community in the 16th century, but had gradually declined, until in 1660 the city was completely destroyed. In the early 18th century, Tiberias was rebuilt by Zahir al-Umar, becoming the center of his rule over Galilee, and seeing also a revival of its Jewish community.

Zionist beginnings

In 1908, Jewish pioneers established the Kinneret Farm at the same time as and next to Moshavat Kinneret in the immediate vicinity of the lake. The farm trained Jewish immigrants in modern farming. One group of youth from the training farm established Kvutzat Degania in 1909–1910, popularly considered as the first kibbutz, another group founded Kvutzat Kinneret in 1913, and yet another the first proper kibbutz, Ein Harod, in 1921, the same year when the first moshav, Nahalal, was established by a group trained at the Farm. The Jewish settlements around Kinneret Farm are considered the cradle of the kibbutz culture of early Zionism; Kvutzat Kinneret is the birthplace of Naomi Shemer (1930–2004), buried at the Kinneret Cemetery next to Rachel (1890–1931)—two of the most prominent national poets.

Borders, customs, water rights

In 1917, the British defeated Ottoman Turkish forces and took control of Palestine, while France took control of Syria. In the carve-up of the Ottoman territories between Britain and France, it was agreed that Britain would retain control of Palestine, while France would control Syria. However, the allies had to fix the border between the Mandatory Palestine and the French Mandate of Syria.[14] The boundary was defined in broad terms by the Franco-British Boundary Agreement of December 1920, which drew it across the middle of the lake.[15] However, the commission established by the 1920 treaty redrew the boundary. The Zionist movement pressured the French and British to assign as many water sources as possible to Mandatory Palestine during the demarcating negotiations. The High Commissioner of Palestine, Herbert Samuel, had sought full control of the Sea of Galilee.[16] The negotiations led to the inclusion into the Palestine territory of the whole Sea of Galilee, both sides of the River Jordan, Lake Hula, Dan spring, and part of the Yarmouk.[17] The final border approved in 1923 followed a 10-meter wide strip along the lake's northeastern shore,[18] cutting the Mandatory Syria (State of Damascus) off from the lake.

The British and French Agreement provided that existing rights over the use of the waters of the river Jordan by the inhabitants of Syria would be maintained; the Government of Syria would have the right to erect a new pier at Semakh on Lake Tiberias or jointly use the existing pier; persons or goods passing between the landing-stage on the Lake of Tiberias and Semakh would not be subject to customs regulations, and the Syrian government would have access to the said landing-stage; the inhabitants of Syria and Lebanon would have the same fishing and navigation rights on Lakes Huleh, Tiberias and River Jordan, while the Government of Palestine would be responsible for policing of lakes.[19]

State of Israel

%252C_Northern_Israel.jpg.webp)

On 15 May 1948, Syria invaded the newborn State of Israel,[20] capturing territory along the Sea of Galilee.[21] Under the 1949 armistice agreement between Israel and Syria, Syria occupied the northeast shoreline of the Sea of Galilee. The agreement, though, stated that the armistice line was "not to be interpreted as having any relation whatsoever to ultimate territorial arrangements." Syria remained in possession of the lake's northeast shoreline until the 1967 Arab-Israeli war.

In the 1950s, Israel formulated a plan to link the Kinneret with the rest of the country's water infrastructure via the National Water Carrier, in order to supply the water demand of the growing country. The carrier was completed in 1964. The Israeli plan, to which the Arab League opposed its own plan to divert the headwaters of the Jordan River, sparked political and sometimes even armed confrontations over the Jordan River basin.

After five years of drought as of 2018, Sea of Galilee is expected to get to the black line.[22] The black elevation line is the lowest depth from which irreversible damage begins and no water can be pumped out any more.[23] Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research describes it as "The black line marks −214.87 m, the lowest-ever level reached since 1926 when the water level record began. According to the water authority, the Kinneret water level must not decline below this level."[24]

In February 2018, the city of Tiberias requested a desalination plant to treat the water coming from the Sea of Galilee and demanded a new water source for the city.[25] March 2018 was the lowest point in water income to the lake since 1927.[26]

In September 2018 the Israeli energy and water office announced a project to pour desalinated water from the Mediterranean Sea into the Sea of Galilee using a tunnel. The tunnel is expected to be the largest of its kind in Israel and will transfer half of the Mediterranean desalted water and will move 300 to 500 million cubic meters of water per year.[27] The plan is said to cost five billion shekels. Giora Eiland led the meetings with German counterparts to find a suitable contractor to build the project.

Archaeology

In 1986 the Ancient Galilee Boat, also known as the Jesus Boat, was discovered on the north-west shore of the Sea of Galilee during a drought when water levels receded. It is an ancient fishing boat from the 1st century AD, and although there is no evidence directly linking the boat to Jesus and his disciples, it nevertheless is an example of the kind of boat that Jesus and his disciples, some of whom were fishermen, may have used.

During a routine sonar scan in 2003 (finding published in 2013),[28] archaeologists discovered an enormous conical stone structure. The structure, which has a diameter of around 230 feet (70 m), is made of boulders and stones. The ruins are estimated to be between 2,000 and 12,000 years old, and are about 10 metres (33 ft) underwater.[29] The estimated weight of the monument is over 60,000 tons. Researchers explain that the site resembles early burial sites in Europe and was likely built in the early Bronze Age.

In February 2018, archaeologists discovered seven intact mosaics with Greek inscriptions. One inscription, one of the longest found to date in western Galilee, gives the names of donors and the names and positions of church officials, including Irenaeus. Another mosaic mentions a woman as a donor to the church's construction. This inscription is the first in the region to mention a female donor.[30]

Water level

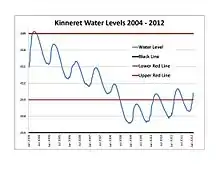

The water level is monitored and regulated. There are three levels at which the alarm is rung:

- The upper red line, 208.9 m (685 ft) below sea level (BSL), where facilities on the shore start being flooded.

- The lower red line, 213.2 m (699 ft) BSL, pumping should stop.

- The black (low-level) line, 214.4 m (703 ft) BSL, irreversible damage occurs.[31]

Daily monitoring of the Sea of Galilee's water level began in 1969, and the lowest level recorded since then was November 2001, which today constitutes the "black line" of 214.87 meters below sea level (although it is believed the water level had fallen lower than the current black line, during droughts earlier in the 20th century). The Israeli government monitors water levels and publishes the results daily at this web page. The level over the past eight years can be retrieved from that site.[32] Increasing water demand in Israel, Lebanon and Jordan, as well as dry winters, have resulted in stress on the lake and a decreasing water line to dangerously low levels at times. The Sea of Galilee is at risk of becoming irreversibly salinized by the salt water springs under the lake, which are held in check by the weight of the freshwater on top of them.[33]

With extreme drought conditions continuing to intensify, the government of Israel approved a plan in 2018 to pump desalinated water into the lake in an effort to stop the water level from plunging below a point where irreversible ecological damage to the lake might take place.[34]

Since the beginning of the 2018–19 rainy season, the Sea of Galilee has risen considerably. From being near the ecologically dangerous l black line of −214.4 m, the level has risen by 16 April 2020 to just 16 cm (6.3 in) below the upper red line, due to strong rains and a radical decrease in pumping.[35] During the entire 2018–19 rainy season the water level rose by a historical record of 3.47 meters (11.4 ft), while the 2019–20 winter brought a 2.82 meters (9 ft 3 in) rise until 16 April, the rainy season not being over yet.[35] The Water Authority has dug a new canal in order to let 5 billion liters (1.1×109 imp gal; 1.3×109 U.S. gal) of water flow from the lake directly into the Jordan River, bypassing the existing dams system for technical and financial reasons.[35]

As at 9 January 2020, the water level was at 211.10 meters (692.6 ft) below sea level. It will be considered full if the water level rises by another 2.3 meters (7 ft 7 in).[36] By 19 January 2020, the water level was 210.715 meters (691.32 ft) below sea level, 1.915 meters (6 ft 3.4 in) short of being considered full.[37] As of 5 April 2020, the water level was 208.8 meters (685 ft) below sea level, the highest level it has been since 2004.[38] On 24 April the level was 208.92 meters (685.4 ft) below sea level.[39]

Water use

Israel's National Water Carrier, completed in 1964, transports water from the lake to the population centers of Israel, and in the past supplied most of the country's drinking water.[40] Nowadays the lake supplies approximately 10% of Israel's drinking water needs.[41]

In 1964, Syria attempted construction of a Headwater Diversion Plan that would have blocked the flow of water into the Sea of Galilee, sharply reducing the water flow into the lake.[42] This project and Israel's attempt to block these efforts in 1965 were factors which played into regional tensions culminating in the 1967 Six-Day War. During the war, Israel captured the Golan Heights, which contain some of the sources of water for the Sea of Galilee.

Up until the mid-2010s, about 400 million m3 (14 billion cu ft) of water was pumped through the National Water Carrier each year.[43] Under the terms of the Israel–Jordan peace treaty, Israel also supplies 50 million m3 (1.8 billion cu ft) of water annually from the lake to Jordan.[44] In recent years the Israeli government has made extensive investments in water conservation, reclamation and desalination infrastructure in the country. This has allowed it to significantly reduce the amount of water pumped from the lake annually in an effort to restore and improve its ecological environment, as well as respond to some of the most extreme drought conditions in hundreds of years affecting the lake's intake basin since 1998. Therefore, it was expected that in 2016 only about 25 million m3 (880 million cu ft) of water would be drawn from the lake for Israeli domestic consumption, a small fraction of the amount typically drawn from the lake over the previous decades.[41]

Tourism

Tourism around the Sea of Galilee is an important economic segment. Historical and religious sites in the region draw both local and foreign tourists. The Sea of Galilee is an attraction for Christian pilgrims who visit Israel to see the places where Jesus performed miracles according to the New Testament, such as his walking on water, calming the storm and feeding the multitude. Alonzo Ketcham Parker, a nineteenth-century American traveler, called visiting the Sea of Galilee "a 'fifth gospel' which one read devoutly, his heart overflowing with quiet joy".[45]

In April 2011, Israel unveiled a 40-mile (64 km) hiking trail in Galilee for Christian pilgrims, called the "Jesus Trail". It includes a network of footpaths, roads and bicycle paths linking sites central to the lives of Jesus and his disciples. It ends at Capernaum on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, where Jesus expounded his teachings.[46]

Another key attraction is the site where the Sea of Galilee's water flows into the Jordan River, to which thousands of pilgrims from all over the world come to be baptized every year.

Israel's most well-known open water swim race, the Kinneret Crossing, is held every year in September, drawing thousands of open water swimmers to participate in competitive and noncompetitive events.[47]

Tourists also partake in the building of rafts on Lavnun Beach, called Rafsodia. Here many different age groups work together to build a raft with their bare hands and then sail that raft across the sea.[48]

Other economic activities include fishing in the lake and agriculture, particularly bananas, dates, mangoes, grapes and olives in the fertile belt of land surrounding it.

The Turkish Aviators Monument, erected during the Ottoman era, stands near Kibbutz Ha'on on the lakeshore, commemorating the Turkish pilots whose monoplanes crashed en route to Jerusalem.[49]

Flora, fauna and ecology

The warm waters of the Sea of Galilee support various flora and fauna, which have supported a significant commercial fishery for more than two millennia. Local flora include various reeds along most of the shoreline as well as phytoplankton. Fauna include zooplankton, benthos and a number of fish species such as Acanthobrama terraesanctae.[6] The Fishing and Agricultural Division of the Ministry of Water and Agriculture of Israel is listing 10 families of fish living in the lake, with a total of 27 species – 19 native and 8 introduced from elsewhere.[50] Local fishermen talk of three types of fish: "مشط musht" (tilapia), sardine (the Kinneret bleak, Acanthobrama terraesanctae), "بني biny" (carp-like), and catfish.[50] The tilapia species include the Galilean tilapia (Sarotherodon galilaeus), the blue tilapia (Oreochromis aureus), and the redbelly tilapia (Tilapia zillii).[50] Fish caught commercially include Tristramella simonis and the Galilean tilapia, locally called "St. Peter's fish".[6] In 2005, 300 short tons (270 t) of tilapia were caught by local fishermen. This dropped to 8 short tons (7.3 t) in 2009 due to overfishing.[51]

A fish species that is unique to the lake, Tristramella sacra, used to spawn in the marsh and has not been seen since the 1990s droughts.[52] Conservationists fear this species may have become extinct.[52]

Low water levels in drought years have stressed the lake's ecology. This may have been aggravated by over-extraction of water for either the National Water Carrier to supply other parts of Israel or, since 1994, for the supply of water to Jordan (see "Water use" section above). Droughts of the early and mid-1990s dried out the marshy northern margin of the lake.[52] It is hoped that drastic reductions in the amount of water pumped through the National Water Carrier will help restore the lake's ecology over the span of several years. The amount planned to be drawn in 2016 for Israeli domestic water use was expected to be less than 10% of the amount commonly drawn on an annual basis in the decades before the mid-2010s.[41]

Important Bird Area

The lake, with its immediate surrounds, has been recognised as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports populations of black francolins and non-breeding griffon vultures as well as many wintering waterbirds, including marbled teals, great crested grebes, grey herons, great white egrets, great cormorants and black-headed gulls.[53]

See also

- Miracles of Jesus

- Sea of Galilee Boat

- The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633 Rembrandt painting

- Tourism in Israel

References

- Aaron T. Wolf, Hydropolitics along the Jordan River Archived 28 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations University Press, 1995

- "Exact-me.org". Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- The Hebrew letter "ת" (Tav) is often transliterated as "Th".

- The 1996-discovered subglacial Lake Vostok challenges both records; it is estimated to be 200 m (660 ft) to 600 m (2,000 ft) below sea level.

- "Kinneret – General" (in Hebrew). Israel Oceanographic & Limnological Research Ltd.

- Data Summary: Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee) Archived 3 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Easton's Revised Bible Dictionary, "Chinnereth". Another speculation is that the name comes from a fruit called in Biblical Hebrew kinar, which is thought to be the fruit of Ziziphus spina-christi.

- Negev, Avraham; Gibson, Shimon, eds. (2001). Kinneret. Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. New York and London: Continuum. p. 285. ISBN 0-8264-1316-1. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- Easton, Gennesaret.

- Israel and You (28 February 2019). "Sea of Galilee – Aerial View *". Israel and You. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- Easton, Tiberias

- "Khirbet Al-Minya". Jalili48. Professor Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh. 12 May 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Stock, Jay T.; Martin, Louise; Jones, Matthew D.; Macdonald, Danielle; Richter, Tobias; Maher, Lisa A. (15 February 2012). "Twenty Thousand-Year-Old Huts at a Hunter-Gatherer Settlement in Eastern Jordan". PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e31447. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731447M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031447. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3280235. PMID 22355366.

- The Preamble of the League of Nations Mandate Archived 21 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Franco-British Convention on Certain Points Connected with the Mandates for Syria and the Lebanon, Palestine and Mesopotamia, signed 23 December 1920. Text available in American Journal of International Law, Vol. 16, No. 3, 1922, 122–126.

- The boundaries of modern Palestine, 1840–1947 (2004), by Gideon Biger. Publisher Rutledge Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7146-5654-0, p. 130.

- The boundaries of modern Palestine, 1840–1947, p. 150. and 130.

- The boundaries of modern Palestine, 1840–1947, p. 145.

- Agreement between His Majesty's Government and the French Government respecting the Boundary Line between Syria and Palestine from the Mediterranean to El Hámmé Archived 9 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Treaty Series No. 13 (1923), Cmd. 1910. Page 7.

- "Israel and the Palestinians – a history – guardian.co.uk – guardian.co.uk". TheGuardian.com.

- "The Year of 1948".

- "שר האנרגיה הכריז: מצב חירום במשק המים – ישראל היום".

- "חדשות – בארץ nrg – מומחים: מצב המים – הקשה מקום המדינה". www.makorrishon.co.il.

- "כנרת – מפלס האגם". kinneret.ocean.org.il.

- קוריאל, אילנה (16 February 2018). "בטבריה חוששים להישאר בלי מים – ומבקשים מתקן התפלה". Ynet.

- להורדה, הרבה יותר נוח לגלוש באפליקציית חדשות 20, לחץ עכשיו. "כמות המים שנכנסה לכנרת היא הנמוכה ביותר שנרשמה מאז 1927 – חדשות 20".

- "מנהרת הענק להצלת הכנרת: "ישראל ביקשה סיוע מגרמניה" | כלכליסט".

- Paz, Yitzhak; Moshe, Reshef; Ben-Avraham, Zvie; Shmuel, Marco; Tibor, Gideon; Nadel, Dani (2013). "A Submerged Monumental Structure in the Sea of Galilee, Israel". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 42 (1): 189–193. doi:10.1111/1095-9270.12005. S2CID 162075355.

- "Mysterious structure found at bottom of ancient lake". CNN.com. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- LOBELL, JARRETT A. "Gods of the Galilee – Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org.

- The Rise and Fall of the Sea of Galilee, Tourism & Nature, 20 February 2019, via Israel Between The Lines, accessed 21 January 2020

- Kinneret Basin Water Level

- Skynews report, 5 May 2009: Race To Save Sea Of Galilee From Disaster Archived 8 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Lidman, Melanie (10 June 2018). "Government approves plan to pump desalinated water into Sea of Galilee". Times of Israel.

- Tzvi Joffre (16 April 2020). "New canal to flow water from Kinneret to Jordan River as water level rises". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Sea of Galilee rises by 23 cm in one day

- Stormy weather batters Israel, causes traffic jams and car accidents

- "Kinneret water level rises 1 cm over weekend, 32 cm to upper red line".

- "Kinneret rises by half a centimeter in a single day".

- "Black gold under the Golan". The Economist. 7 November 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- Amit, Hagai (1 June 2016). "הקו האדום של הכנרת נהפך לבעיה של הירדנים" [The Kinneret's Red Line has Turned into Jordan's Problem]. TheMarker. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Fischhendler, Itay (2008). "When Ambiguity in Treaty Design Becomes Destructive: A Study of Transboundary Water". Global Environmental Politics. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- Shmuel Kantor. "The National Water Carrier".

- "Developments related to the Middle East Peace Process". UN. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- Parker, A. K., "The Sea of Galilee" in The Biblical World, Vol. 7, No. 4 (April 1896), pages 264–272

- Daniel Estrin, Canadian Press (15 April 2011). "Israel unveils hiking trail in Galilee for Christian pilgrims". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- Tchetchik, Daniel (18 September 2017). "In Photos: Over 10,000 Swimmers Brave Lake Kinneret in Annual Sea of Galilee Event". Haaretz. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- "The International Rafsodia – Crossing the Kinneret on a Raft". Keren Kayemeth Leisrael Jewish National Fund. 19 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- A determined path, Jerusalem Post

- Dr. Rafael D. Guererro III (5 May 2018). "St. Peter's Fish in Israel". Agriculture Monthly. Manila, Philippines (August 2015). Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Still Fishers of Men". Vermont Catholic. 1 (12): 3. June 2010.

- Goren, M. (2014). "Tristramella sacra". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T61372A19010617. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T61372A19010617.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- "Lake Kinneret and Kinerot". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

Further reading

- Tamar Zohary, Assaf Sukenik, Tom Berman (2014). Lake Kinneret: Ecology and Management. Springer. ISBN 9789401789448.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - C. Serruya (1978). Lake Kinneret. ISBN 90-6193-085-5.

External links

- World Lakes Database entry for Sea of Galilee

- Kinneret Data Center // Kinneret Limnological Laboratory

- Sea of Galilee – official government page (Hebrew).

- Sea of Galilee water level (Hebrew) // official government page

- Database: Water levels of Sea of Galilee since 1966 (Hebrew)

- Bibleplaces.com: Sea of Galilee

- Updated elevation of the Kinneret's level (Hebrew). Elevation (meters below sea level) is shown on the line following the date line.

.jpg.webp)