The Jungle

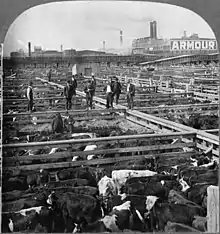

The Jungle is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair (1878–1968).[1] The novel portrays the harsh conditions and exploited lives of immigrants in the United States in Chicago and similar industrialized cities. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States.[2] However, most readers were more concerned with several passages exposing health violations and unsanitary practices in the American meat packing industry during the early 20th century, which greatly contributed to a public outcry that led to reforms including the Meat Inspection Act.

_cover.jpg.webp) First edition | |

| Author | Upton Sinclair |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Political fiction |

| Publisher | Doubleday, Page & Co. |

Publication date | February 26, 1906 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 413 |

| OCLC | 1150866071 |

The book depicts working-class poverty, lack of social supports, harsh and unpleasant living and working conditions, and hopelessness among many workers. These elements are contrasted with the deeply rooted corruption of people in power. A review by the writer Jack London called it "the Uncle Tom's Cabin of wage slavery."[3]

Sinclair was considered a muckraker, a journalist who exposed corruption in government and business.[4] In 1904, Sinclair had spent seven weeks gathering information while working incognito in the meatpacking plants of the Chicago stockyards for the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason. He first published the novel in serial form in 1905 in the newspaper, and it was published as a book by Doubleday in 1906.

Plot summary

Jurgis Rudkus marries his fifteen-year-old sweetheart, Ona Lukoszaite, in a joyous traditional Lithuanian wedding feast. They and their extended family have recently immigrated to Chicago due to financial hardship in Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire). They have heard that America offers freedom and higher wages and have come to pursue the American Dream.

Despite having lost much of their savings being conned on the trip to Chicago, and then having to pay for the wedding—and despite the disappointment of arriving at a crowded boarding house—Jurgis is initially optimistic about his prospects in Chicago. Young and strong, he believes that he is immune to the misfortunes that have befallen others in the crowd. He is swiftly hired by a meatpacking factory; he marvels at its efficiency, even while witnessing the cruel treatment of the animals.

The women of the family answer an ad for a four-room house; Ona, who came from an educated background, figures that they could easily afford it with the jobs that Jurgis, proud Marija, and ambitious Jonas have gotten. While they discover at the showing that the neighborhood is unkempt and the house doesn't live up to the advertisement, they are taken in by the slickness and fluent Lithuanian of the real estate agent and sign a contract for the house.

However, with the help of an old Lithuanian neighbor, they discover several unexpected expenses in the contract that they must pay every month on time, or else face eviction—the fate of most home buyers in the neighborhood. To meet these costs, Ona and thirteen-year-old Stanislovas (whom the family had wished to send to school) must take up work as well.

While sickness befalls them often, they cannot afford not to work. That winter, Jurgis's father, weakened by exposure to chemicals and the elements at his job, dies of illness.

Some levity is brought to their lives by the arrival of a musician, named Tamoszius, who courts Marija, and the birth of Jurgis and Ona's first child. However, this happiness is tempered when Ona must return to work one week after giving birth, and Marija is laid off in a seasonal cutback. Jurgis attends union meetings passionately; he realizes that he had been taken in by a vote-buying scheme when he was new to Chicago, learns that the meat factories deliberately use diseased meat, and learns that workers frequently came down with ailments relating to their dangerous and unsanitary work.

Work becomes more demanding as wages fall; the working members of the family suffer a series of injuries. Amid this hardship, Jonas deserts the family, leaving them no choice but to send two children to work as newspaper boys. The youngest child, a handicapped toddler, dies of food poisoning; only his mother grieves his death.

After recovering from his injury, Jurgis takes the least desirable job at a fertilizer mill. In misery, he begins drinking alcohol. He becomes suspicious of his pregnant wife's failure to return home on several nights. Ona ultimately confesses that her boss, Phil Connor, raped her. Then, by threatening to fire and blacklist everyone in her family, he coerced her into a continuing sexual relationship.

Jurgis furiously attacks Connor at his factory, but half a dozen men tear him away. While in prison awaiting trial, he realizes it is Christmas Eve. The next day, his cellmate, Jack Duane, tells him about his criminal ventures and gives him his address. At trial, Connor testifies that he had fired Ona for "impudence" and easily denies Jurgis's account; the judge dismissively sentences Jurgis to thirty days in prison plus court fees.

Stanislovas visits Jurgis in prison and tells him of the family's increasing destitution. After Jurgis serves his term (plus three days for his inability to pay the fees), he walks through the slush for an entire day to get home, only to find that the house had been remodeled and sold to another family. He learns from their old neighbor that, despite all of the sacrifices they had made, his family had been evicted and had returned to the boarding house.

Upon arriving at the boarding house, Jurgis hears Ona screaming. She is in premature labor, and Marija explains that the family had no money for a doctor. Jurgis convinces a midwife to assist, but it is too little too late; the infant is dead, and with one last look at Jurgis, Ona dies shortly afterward. The children return with a day's wages; Jurgis spends all of it to get drunk for the night.

The next morning, Ona's stepmother begs Jurgis to think of his surviving child. With his son in mind, he endeavors again to gain employment despite his blacklisting. For a time, the family gets by and Jurgis delights in his son's first attempts at speech. One day, Jurgis arrives home to discover that his son had drowned after falling off a rotting boardwalk into the muddy streets. Without shedding a tear, he walks away from Chicago.

Jurgis wanders the countryside while the weather is warm, working, foraging, and stealing for food, shelter, and drink. In the fall, he returns to Chicago, sometimes employed, sometimes a tramp. While begging, he chances upon an eccentric rich drunk—the son of the owner of the first factory where Jurgis had worked—who entertains him for the night in his luxurious mansion and gives him a one-hundred-dollar bill (worth about $3000 today). Afterward, when Jurgis spends the bill at a bar, the bartender cheats him. Jurgis attacks the bartender and is sentenced to prison again, where he once again meets Jack Duane. This time, without a family to anchor him, Jurgis decides to fall in with him.

Jurgis helps Duane mug a well-off man; his split of the loot is worth over twenty times a day's wages from his first job. Though his conscience is pricked by learning of the man's injuries in the next day's papers, he justifies it to himself as necessary in a "dog-eat-dog" world. Jurgis then navigates the world of crime; he learns that this includes a substantial corruption of the police department. He becomes a vote fixer for a wealthy political powerhouse, Mike Scully, and arranges for many new Slavic immigrants to vote according to Scully's wishes—as Jurgis once had. To influence those men, he had taken a job at a factory, which he continues as a strikebreaker. One night, by chance, he runs into Connor, whom he attacks again. Afterward, he discovers that his buddies cannot fix the trial as Connor is an important figure under Scully. With the help of a friend, he posts and skips bail.

With no other options, Jurgis returns to begging and chances upon a woman who had been a guest to his wedding. She tells him where to find Marija, and Jurgis heads to the address to find that it is a brothel being raided by the police. Marija tells him that she was forced to prostitute herself to feed the children after they had gotten sick, and Stanislovas—who had drunk too much and passed out at work—had been eaten by rats. After their speedy trial and release, Marija tells Jurgis that she cannot leave the brothel as she cannot save money and has become addicted to heroin, as is typical in the brothel's human trafficking.

Marija has a customer, so Jurgis leaves and finds a political meeting for a warm place to stay. He begins to nod off. A refined lady gently rouses him, saying, "If you would try to listen, comrade, perhaps you would be interested." Startled by her kindness and fascinated by her passion, he listens to the thundering speaker. Enraptured by his speech, Jurgis seeks out the orator afterward. The orator asks if he is interested in socialism.

A Polish socialist takes him into his home, conversing with him about his life and socialism. Jurgis returns home to Ona's stepmother and passionately converts her to socialism; she placatingly goes along with it only because it seems to motivate him to find work. He finds work in a small hotel that turns out to be run by a state organizer of the Socialist Party. Jurgis passionately dedicates his life to the cause of socialism.

Characters

.tiff.png.webp)

- Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian who immigrates to the US and struggles to support his family.

- Ona Lukoszaite Rudkus, Jurgis' teenage wife.

- Marija Berczynskas, Ona's cousin. She dreams of marrying a musician. After Ona's death and Rudkus' abandonment of the family, she becomes a prostitute to help feed the few surviving children.

- Teta Elzbieta Lukoszaite, Ona's stepmother. She takes care of the children and eventually becomes a beggar.

- Grandmother Swan, another Lithuanian immigrant.

- Dede Antanas, Jurgis' father. He contributes work despite his age and poor health; dies from a lung infection.

- Jokubas Szedvilas, Lithuanian immigrant who owns a deli on Halsted Street.

- Edward Marcinkus, Lithuanian immigrant and friend of the family.

- Fisher, Chicago millionaire whose passion is helping poor people in slums.

- Tamoszius Kuszleika, a fiddler who becomes Marija's fiancé.

- Jonas Lukoszas, Teta Elzbieta's brother. He abandons the family in bad times and disappears.

- Stanislovas Lukoszas, Elzibeta's eldest son; he starts work at 14, with false documents that say he is 16.

- Mike Scully (originally Tom Cassidy), the Democratic Party "boss" of the stockyards.

- Phil Connor, a boss at the factory where Ona works. Connor rapes Ona and forces her into prostitution.

- Miss Henderson, Ona's forelady at the wrapping-room.

- Antanas, son of Jurgis and Ona, otherwise known as "Baby".

- Vilimas and Nikalojus, Elzbieta's second and third sons.

- Kristoforas, a crippled son of Elzbieta.

- Juozapas, another crippled son of Elzbieta.

- Kotrina, Elzbieta's daughter and Ona's half sister.

- Judge Pat Callahan, a crooked judge.

- Jack Duane, a thief whom Rudkus meets in prison.

- Madame Haupt, a midwife hired to help Ona.

- Freddie Jones, son of a wealthy beef baron.

- Buck Halloran, an Irish "political worker" who oversees vote-buying operations.

- Bush Harper, a man who works for Mike Scully as a union spy.

- Ostrinski, a Polish immigrant and socialist.

- Tommy Hinds, the socialist owner of Hinds's Hotel.

- Mr. Lucas, a socialist pastor and itinerant preacher.

- Nicholas Schliemann, a Swedish philosopher and socialist.

- Durham, a businessman and Jurgis's second employer.

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

|

Publication history

Sinclair published the book in serial form between February 25, 1905, and November 4, 1905, in Appeal to Reason, the socialist newspaper that had supported Sinclair's undercover investigation the previous year. This investigation had inspired Sinclair to write the novel, but his efforts to publish the series as a book met with resistance. An employee at Macmillan wrote,

I advise without hesitation and unreservedly against the publication of this book which is gloom and horror unrelieved. One feels that what is at the bottom of his fierceness is not nearly so much desire to help the poor as hatred of the rich.[5]

Five publishers rejected the work as it was too shocking.[6] Sinclair was about to self-publish a shortened version of the novel in a "Sustainer's Edition" for subscribers when Doubleday, Page came on board; on February 28, 1906 the Doubleday edition was published simultaneously with Sinclair's of 5,000 which appeared under the imprint of “The Jungle Publishing Company” with the Socialist Party’s symbol embossed on the cover, both using the same plates.[7] In the first six weeks, the book sold 25,000 copies.[8] It has been in print ever since, including four more self-published editions (1920, 1935, 1942, 1945).[7] Sinclair dedicated the book "To the Workingmen of America".[9]

All works published in the United States before 1924 are in the public domain,[10] so there are free copies of the book available on websites such as Project Gutenberg[11] and Wikisource.[12]

Uncensored editions

In 1988, St. Lukes Press, a division of Peachtree Publishers Ltd, published an edition titled "The Lost First Edition of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle" based on the original serialized version of "The Jungle" as seen in "Appeal to Reason". This version was edited by Gene Degruson of Pittsburg State University, based on a correspondence regarding the novel found in the basement of a farm in Girard, Kansas. The book included an introductory essay by DeGruson detailing the process of how he "restored" the text. [13]

In 2003, See Sharp Press published an edition based on the original serialization of The Jungle in Appeal to Reason, which they described as the "Uncensored Original Edition" as Sinclair intended it. The foreword and introduction say that the commercial editions were censored to make their political message acceptable to capitalist publishers.[14] Others argue that Sinclair had made the revisions himself to make the novel more accurate and engaging for the reader, corrected the Lithuanian references, and streamlined to eliminate boring parts, as Sinclair himself said in letters and his memoir American Outpost (1932).[7]

Reception

Upton Sinclair intended to expose "the inferno of exploitation [of the typical American factory worker at the turn of the 20th Century]",[15] but the reading public fixed on food safety as the novel's most pressing issue. Sinclair admitted his celebrity arose "not because the public cared anything about the workers, but simply because the public did not want to eat tubercular beef".[15]

Sinclair's account of workers falling into rendering tanks and being ground along with animal parts into "Durham's Pure Leaf Lard" gripped the public. The poor working conditions, and exploitation of children and women along with men, were taken to expose the corruption in meat packing factories.

The British politician Winston Churchill praised the book in a review.[16]

Bertolt Brecht took up the theme of terrible working conditions at the Chicago Stockyards in his play Saint Joan of the Stockyards (German: Die heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe), transporting Joan of Arc to that environment.

In 1933, the book became a target of the Nazi book burnings due to Sinclair's endorsement of socialism.[17]

Federal response

President Theodore Roosevelt had described Sinclair as a "crackpot" because of the writer's socialist positions.[18] He wrote privately to journalist William Allen White, expressing doubts about the accuracy of Sinclair's claims: "I have an utter contempt for him. He is hysterical, unbalanced, and untruthful. Three-fourths of the things he said were absolute falsehoods. For some of the remainder there was only a basis of truth."[19] After reading The Jungle, Roosevelt agreed with some of Sinclair's conclusions. The president wrote "radical action must be taken to do away with the efforts of arrogant and selfish greed on the part of the capitalist."[20] He assigned the Labor Commissioner Charles P. Neill and social worker James Bronson Reynolds to go to Chicago to investigate some meat packing facilities.

Learning about the visit, owners had their workers thoroughly clean the factories prior to the inspection, but Neill and Reynolds were still revolted by the conditions. Their oral report to Roosevelt supported much of what Sinclair portrayed in the novel, excepting the claim of workers falling into rendering vats.[21] Neill testified before Congress that the men had reported only "such things as showed the necessity for legislation."[22] That year, the Bureau of Animal Industry issued a report rejecting Sinclair's most severe allegations, characterizing them as "intentionally misleading and false", "willful and deliberate misrepresentations of fact", and "utter absurdity".[23]

Roosevelt did not release the Neill–Reynolds Report for publication. His administration submitted it directly to Congress on June 4, 1906.[24] Public pressure led to the passage of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act; the latter established the Bureau of Chemistry (in 1930 renamed as the Food and Drug Administration).

Sinclair rejected the legislation, which he considered an unjustified boon to large meatpackers. The government (and taxpayers) would bear the costs of inspection, estimated at $30,000,000 annually.[25][26] He complained about the public's misunderstanding of the point of his book in Cosmopolitan Magazine in October 1906 by saying, "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach."[27]

Adaptations

The first film version of the novel was made in 1914, but it has since been lost.[28]

See also

- Labor rights in American meatpacking industry

- Investigative journalism

- Watchdog journalism

References

- Brinkley, Alan (2010). "17: Industrial Supremacy". The Unfinished Nation. McGrawHill. ISBN 978-0-07-338552-5.

- Van Wienen, Mark W. (2012). "American socialist triptych: the literary-political work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Upton Sinclair, and W.E.B. Du Bois. n.p.". Book Review Digest Plus (H.W. Wilson). University of Michigan Press.

- "Upton Sinclair", Social History (biography), archived from the original (blog) on 2012-05-27.

- Sinclair, Upton, "Note", 'The Jungle, Dover Thrift, pp. viii–x

- Upton Sinclair, Spartacus Educational.

- Gottesman, Ronald. "Introduction". The Jungle. Penguin Classics.

- Phelps, Christopher. "The Fictitious Suppression of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle". History News Network. George Mason University. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- "The Jungle and the Progressive Era | The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. 2012-08-28. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- Bloom, Harold, ed. (2002), Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, Infohouse, pp. 50–51, ISBN 1604138874.

- "Copyright Basics FAQ". Stanford Copyright and Fair Use Center. 2013-03-27. Retrieved 2020-07-08.

- Sinclair, Upton. The Jungle. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- – via Wikisource.

- Sinclair, Upton (1988). The Lost First Edition of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle. Atlanta, GA: St. Lukes Press. ISBN 0918518660.

- Sinclair, Upton (1905). The Jungle: The Uncensored Original Edition. Tucson, AZ: See Sharp Press. p. vi. ISBN 1884365302.

- Sullivan, Mark (1996). Our Times. New York: Scribner. p. 222. ISBN 0-684-81573-7.

- Arthur, Anthony (2006), Radical Innocent: Upton Sinclair, New York: Random House, pp. 84–85.

- "Banned and/or Challenged Books from the Radcliffe Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of the 20th Century". American Library Association. March 26, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- Oursler, Fulton (1964), Behold This Dreamer!, Boston: Little, Brown, p. 417.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1951–54) [July 31, 1906], Morison, Elting E (ed.), The Letters, vol. 5, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 340.

- "Sinclair, Upton (1878–1968)". Blackwell Reference Online. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- Jacobs, Jane (2006), "Introduction", The Jungle, ISBN 0-8129-7623-1.

- Hearings Before the Committee on Agriculture... on the So-called "Beveridge Amendment" to the Agricultural Appropriation Bill, U.S. Congress, House, Committee on Agriculture, 1906, p. 102, 59th Congress, 1st Session.

- Hearings Before the Committee on Agriculture... on the So-called "Beveridge Amendment" to the Agricultural Appropriation Bill, U.S. Congress, House, Committee on Agriculture, 1906, pp. 346–50, 59th Congress, 1st Session.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1906), Conditions in Chicago Stockyards (PDF)

- Young, The Pig That Fell into the Privy, p. 477.

- Sinclair, Upton (1906), "The Condemned-Meat Industry: A Reply to Mr. M. Cohn Armour", Everybody's Magazine, vol. XIV, pp. 612–13.

- Bloom, Harold. editor, Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, Infobase Publishing, 2002, p. 11

- "The Jungle". silentera.com.

Further reading

- Bachelder, Chris (January–February 2006). "The Jungle at 100: Why the reputation of Upton Sinclair's good book has gone bad". Mother Jones Magazine.

- Lee, Earl. "Defense of The Jungle: The Uncensored Original Edition". See Sharp Press.

- Øverland, Orm (Fall 2004). "The Jungle: From Lithuanian Peasant to American Socialist". American Literary Realism. 37 (1): 1–24.

- Phelps, Christopher. "The Fictitious Suppression of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle". hnn.us.

- Young, James Harvey (1985). "The Pig That Fell into the Privy: Upton Sinclair's The Jungle and Meat Inspection Amendments of 1906". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 59 (1): 467–480. PMID 3912019.

External links

- The Jungle at Standard Ebooks

- The Jungle, available at Internet Archive (scanned books first edition)

- The Jungle at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML)

The Jungle public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Jungle public domain audiobook at LibriVox- The Jungle serialized in The Sun newspaper from the Florida Digital Newspaper Library

- PBS special report marking the 100th anniversary of the novel

- Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism revisits The Jungle