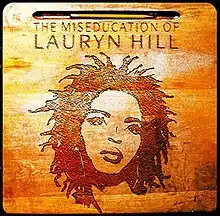

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill is the debut solo album by American singer and rapper Lauryn Hill. It was released on August 25, 1998, by Ruffhouse Records and Columbia Records. The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill is a neo soul and R&B album with some songs based in hip hop soul and reggae. Its lyrics touch upon Hill's pregnancy and the turmoil within her former group the Fugees, along with themes of love and God. The album's title was inspired by the film and autobiographical novel The Education of Sonny Carson, and Carter G. Woodson's The Mis-Education of the Negro.

| The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | August 25, 1998 | |||

| Recorded | September 1997 – June 1998 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 77:39 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Lauryn Hill chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill | ||||

| ||||

After touring with the Fugees, Hill became involved in a romantic relationship with Jamaican entrepreneur Rohan Marley, and shortly after, became pregnant with their child. This pregnancy, as well as other circumstances in her life, inspired Hill to make a solo album. Recording sessions for the album took place from late 1997 to June 1998 mainly at Tuff Gong Studios in Kingston, as Hill collaborated with a group of musicians known as New Ark in writing and producing the songs.

The album debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 chart, selling over 422,000 copies in its first week, which broke a record for first-week sales by a female artist. It was promoted with the release of the hit singles "Doo Wop (That Thing)", "Ex-Factor", and "Everything Is Everything", while "Lost Ones" and "Can't Take My Eyes Off You" were released as promotional singles.[2] To further promote the album, Hill made televised performances on Saturday Night Live and the Billboard Music Awards before embarking on a sold-out, worldwide concert tour.

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill was among the most acclaimed albums of 1998, as most critics praised Hill's presentation of a woman's view on life and love, along with her artistic range. At the 41st Annual Grammy Awards, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill earned 10 nominations, winning five awards, making Hill the first woman to receive that many nominations and awards in one night. The album's success propelled Hill to international superstardom, and contributed to bringing hip hop and neo soul to the forefront of popular music. New Ark, however, felt Hill and her record label did not properly credit the group on the album; a lawsuit filed by the group was settled out of court in 2001.

Since its release, the album has been ranked in numerous best-album lists, with a number of critics regarding it as one of the greatest albums of the 1990s, as well as one of the greatest albums of all time. Among its honors are inclusion in Rolling Stone magazine's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list, Harvard University's Loeb Music Library, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American history, and the Library of Congress' National Recording Registry. In 2021, the album was certified Diamond by the Recording Industry Association of America, for estimated sales of 10 million copies in the US, making Hill the first female rapper to accomplish this feat.[3] Worldwide, the album has sold over 20 million copies, making it one of the best-selling albums of all time, the best-selling album by a female rapper,[4] and the best-selling neo-soul album of all time.[5] It remains Hill's only studio album.

Background

In 1996, Lauryn Hill met Rohan Marley while touring as a member of the Fugees. The two gradually formed a close relationship, and while on tour, Hill became pregnant with his child.[6] The pregnancy and other circumstances in her life inspired her to record a solo album. After contributing to fellow Fugees member Wyclef Jean's 1997 solo record Wyclef Jean Presents The Carnival, Hill took time off from touring and recording due to her pregnancy and cases of writer's block.[7] This pregnancy, however, renewed Hill's creativity, as she recalled in an interview several years later: "When some women are pregnant, their hair and their nails grow, but for me it was my mind and ability to create. I had the desire to write in a capacity that I hadn't done in a while. I don't know if it's a hormonal or emotional thing ... I was very in touch with my feelings at the time." Of the early writing process, Hill said, "Every time I got hurt, every time I was disappointed, every time I learned, I just wrote a song."[8]

While inspired, Hill wrote over thirty songs in her attic studio in South Orange, New Jersey.[9] Many of these songs drew upon the turbulence in the Fugees, as well as past love experiences.[10] In the summer of 1997, as Hill was due to give birth to her first child, she was requested to write a song for gospel musician CeCe Winans.[9] Several months later, she went to Detroit to work with soul singer Aretha Franklin, writing and producing her single "A Rose is Still a Rose". Franklin would later have Hill direct the song's music video.[11] Shortly after this, Hill did writing work for Whitney Houston.[12] Having written songs for artists in gospel, hip hop, and R&B, she drew on these influences and experiences to record The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.[13]

Recording and production

_1.jpg.webp)

Hill began recording The Miseducation in late 1997 at Chung King Studios in New York City,[14] and completed it in June 1998 at Tuff Gong Studios in Kingston, Jamaica.[15] In an interview, Hill described the first day of recording, stating: "The first day in the studio I ordered every instrument I ever fell in love with: harps, strings, timpani, organs, clarinets. It was my idea to record it so the human element stayed in. I didn't want it to be too technically perfect."[16] Initially, Jean did not support Hill recording a solo album, but eventually offered to help as a producer, which she did not accept.[17][18] Aside from doing work at Chung King Studios, Hill also recorded at Perfect Pair Studios in New Jersey, as well as Sony Studios,[19] with some songs having different elements recorded at different studios.[19] The bulk of the album, however, was recorded at Tuff Gong Studios in Kingston, Jamaica, the studio built by reggae musician Bob Marley.[20] Regarding this shift in environment, Hill stated: "When I started recording in New York and New Jersey, lots of people were talking to me about going different routes. I could feel people up in my face, and I was picking up on bad vibes. I wanted a place where there was good vibes, where I was among family, and it was Tuff Gong."[21] Many members of the Marley family were present in the studio during the recording sessions, among them Julian Marley, who added guitar elements to "Forgive Them Father."[20]

In an interview, recording engineer Gordon "Commissioner Gordon" Williams recalled the recording of "Lost Ones", stating: "It was our first morning in Jamaica and I saw all of these kids gathered around Lauryn, screaming and dancing. Lauryn was in the living room next to the studio with about fifteen Marley grandchildren around her, the children of Ziggy, and Stephen, and Julian, and she starts singing this rap verse, and all the kids start repeating the last word of each line, chiming in very spontaneously because they were so into the song."[22] Columbia Records considered bringing in an outside producer for the album and had early talks with RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan. However, Hill was adamant about writing, arranging, and producing the album herself: "It would have been more difficult to articulate to other people. Hey, it's my album. Who can tell my story better than me?"[23] She recalled Ruffhouse Records executive Chris Swartz ensuring her artistic freedom while recording the album: "I had total control of the album. Chris Swartz at Ruffhouse, my label, said, 'Listen, you've never done anything stupid thus far, so let me let you do your thing.'"[24]

Music and lyrics

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill is considered a neo soul album, according to Christopher John Farley of Time[30] and Rhapsody writer Mosi Reeves;[31] Complex magazine refers to it more generally as R&B.[32] Its music incorporates styles such as soul, hip hop, and reggae,[33] with some songs based in hip hop soul, according to the Encyclopedia of African American Music (2010).[34] "When It Hurts So Bad" is musically old roots reggae mixed with soul. While mostly in English, "Forgive Them Father" and "Lost Ones" both feature singing in patois, which is the common dialect in Jamaica. Although heavily R&B, the song "Superstar" contains an interpolation of the rock song "Light My Fire" by The Doors. Hill said that she "didn't want to come out with a [Fugees] type of sound", but create "something that was uniquely and very clearly a Lauryn Hill album."[24] She also said that she did not intend for the album's sound to be commercially appealing: "There's too much pressure to have hits these days. Artists are watching Billboard instead of exploring themselves. Look at someone like Aretha, she didn't hit with her first album, but she was able to grow up and find herself. I wanted to make honest music. I don't like things to be too perfect, or too polished. People may criticize me for that, but I grew up listening to Al Green and Sam Cooke. When they hit a high note, you actually felt it."[35]

Much of Hill's lyrics dealt with motherhood, the Fugees, reminiscence, love, heartbreak, and God.[9] Commenting on the album's gospel content, Hill stated "Gospel music is music inspired by the gospels. In a huge respect, a lot of this music turned out to be just that. During this album, I turned to the Bible and wrote songs that I drew comfort from."[38] Several of the album's songs, such as "Lost Ones," "Superstar," "Ex-Factor" and "Forgive Them Father" were widely speculated as direct attacks at Fugee members Wyclef and Pras.[39][40] "Ex-Factor" was originally intended for a different artist, however, Hill decided to keep it after it was completed, due to its personal content.[41] Although a large portion of the album's love songs would turn out to be bitter from Hill's previous relationship, "Nothing Even Matters,"[42] a duet performed by Hill and R&B singer D'Angelo, showcased a brighter, more intimate perspective on the subject. The song was inspired by Hill's relationship with Rohan Marley. Speaking about "Nothing Even Matters"' lyrics, Hill remarked: "I wanted to make a love song, á la Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway, and give people a humanistic approach to love again without all the physicality and overt sexuality."[43]

"To Zion," among the more introspective tracks on the album, spoke about how Hill's family comes before her career[25] and her decision to have her first child, even though many at the time encouraged her to abort the pregnancy, so as to not conflict with her burgeoning career.[40] In an interview she discussed the song's origin and significance, commenting "Names wouldn't come when I was ready to have him. The only name that came to me was Zion. I was like, 'is Zion too much of a weight to carry?' But this little boy, man. I would say he personally delivered me from my emotional and spiritual drought. He just replenished my newness. When he was born, I felt like I was born again."[44] She further stated: "I wanted it to be a revolutionary song about a spiritual movement, and also about my spiritual change, going from one place to another because of my son."[45]

Throughout The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, several interludes of a teacher speaking to what is implied to be a classroom of children are played. The "teacher" was played by American poet and politician Ras Baraka speaking to a group of children in the living room of Hill's New Jersey home.[40] Hill requested that Baraka speak to the children about the concept of love, to which he improvised in the lecture.[40] Slant Magazine's Paul Schrodt remarked on the title's reference to Carter G. Woodson's The Mis-Education of the Negro: "[Hill] adopts Woodson's thesis and makes it part of her own artistic process. Like the songs themselves, the intro/outro classroom scenes suggest a larger community working to redefine itself."[26] Along with Woodson's book, the album's title was inspired by the film and autobiographical novel The Education of Sonny Carson.[40]

Marketing and sales

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill was released on August 25, 1998.[25] It was promoted with three singles—"Doo Wop (That Thing)", "Ex-Factor", and "Everything Is Everything"; all of which became hits and produced popular music videos.[46] The album broke numerous sales records.[47] In its first week, it debuted at number one on the Billboard 200,[48] becoming the first album by a solo female rapper to peak or debut at number one in the US.[49][50] Its first-week sales of over 422,000 copies broke the then record for female artists, previously held by Madonna's Ray of Light (1998),[51] and became the first debut album by a female artist to debut at number one on the Billboard 200 chart,[52] and additionally made Hill the first act to have debuted at number one on both the Billboard 200 and Hot 100 with their first entries on each chart.[53] Its first-week sales remained the highest first-week sales for a debut album by a female artist in the 20th century,[54][55] and the highest for a female rapper ever.[56]

It topped the Billboard 200 for a second consecutive week, during which it sold 265,000 copies;[57] and earned a gold certification by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) after two weeks.[58] In the United States, the album had sold one million copies in less than a month and 2.9 million copies by the end of the year, becoming one of the best-selling albums of 1998.[59] Furthermore, it was the top rap album of the year according to Billboard, topping the Billboard Year-End Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart,[60] making it the only album by a female artist to accomplish this feat.[61] In Ireland, the album became the first rap album to reach number one on the Irish Albums Chart.[62] In Japan, it sold over one million copies in its first few months, and became one of the few million-certified albums by the Recording Industry Association of Japan.[63]

The album's sales increased after Hill's appearance at the 41st Annual Grammy Awards, as it sold 234,000 more copies in the week of March 3, 1999,[64] and 200,000 copies the following week.[65] By August, it had sold 10 million copies worldwide, including nearly 700,000 in Canada.[66] In April 2002, Columbia said that the album had sold 12 million copies worldwide,[67] and by 2009, its global sales were reported to be 19 million copies.[68] As of 2018, it is the most-streamed album released in 1998, on Spotify.[69] The album also held the record for the longest-charting debut album by a female rapper on the Billboard 200, at 92 weeks, for over 21 years before being surpassed by Cardi B's Invasion of Privacy (2018).[70] In 2021, it was certified diamond by the RIAA,[71] earning Hill the Guinness World Record for being the first female rapper to reach RIAA diamond status.[72] It was also reported that the album has sold 20 million copies worldwide according to Sony Music.[73][74][75]

Tour

Initially, there was no immediate tour planned due to the album not needing further promotion. Hill was also pregnant again with a child due in September 1998.[76] Her first live performances of the songs were at Saturday Night Live and the Billboard Music Awards.[77] In January 1999, Hill recruited a band and began rehearsals for what would become The Miseducation Tour.[78] Tickets sold out as soon as the tour was announced.[76]

The tour began at Budokan in Tokyo on January 21, 1999. Hill performed there again the following night, and played at two other Tokyo venues in the following week.[76] One week later, she flew to London for her performance at the Brixton Academy on February 8.[76] With 20 US dates total,[79] the American part of the tour, which featured Outkast as the opening act, started on February 18 in Detroit, and ended on April 1 in Hill's hometown of Newark, New Jersey.[79] She began the tour's 14-date European leg on May 13, when she performed at the Oslo Spektrum in Norway, closing on June 2 at the Manchester Arena in England.[80] She then returned to Japan, where the tour was completed.[81]

Hill did not want an extensive tour because of obligations to her family and the difficulties she experienced touring with the Fugees in 1996, which she found desensitizing and isolating. According to Hill biographer Chris Nickson in 1999, "there was the possibility of more dates being added ... but it was unlikely that Lauryn would be willing to make the tour more grueling and draining. She'd come to know that there was much more to life than a career."[81]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Entertainment Weekly | A[82] |

| The Guardian | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| Melody Maker | |

| Muzik | |

| NME | 8/10[37] |

| Pitchfork | 9.5/10 |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Spin | 9/10[29] |

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill was met with widespread critical acclaim;[88][89] according to Los Angeles Times journalist Geoff Boucher, it was the most acclaimed album of 1998. Reviewers frequently praised Hill's presentation of a female's view on life and love.[90] Eric Weisbard from Spin called her a "genre-bender" whose confident singing and rapping was balanced by vulnerable themes and sentiment.[29] In The New York Times, Ann Powers found it "miraculous" and "exceptional" for Hill to use "her faith, based more in experience and feeling than in doctrine," as a means of connecting "the sacred to the secular in music that touches the essence of soul."[91] AllMusic's John Bush was impressed by how she produced most of the album, "not as a crossover record, but as a collection of overtly personal and political statements", while demonstrating "performing talents, vocal range, and songwriting smarts".[25] David Browne, writing in Entertainment Weekly, called it "an album of often-astonishing power, strength, and feeling", as well as "one of the rare hip-hop soul albums" to not lose focus with frivolous guest appearances. Browne applauded Hill's artistic vision and credited her for "easily flowing from singing to rapping, evoking the past while forging a future of her own".[82] Dream Hampton of The Village Voice said she seamlessly "travels her realm within any given song",[92] while Chicago Tribune critic Greg Kot deemed the record a "vocal tour de force" with arrangements that "bristle with great ideas".[93] The album was the first in the history of XXL to receive a perfect "XXL" rating,[94] with the magazine saying that it "not only verifies [Hill] as the most exciting voice of a young, progressive hip-hop nation, it raises the standards for it."[95]

In a less enthusiastic review, Q magazine's Dom Phillips felt the music's only flaw was "a lack of memorable melody" on some songs that did not use interesting samples,[87] while John Mulvey from NME quibbled about what he felt were redundant skits and Hill's "propensity" for histrionics and declarations of "how brilliant God is" on an otherwise "essential" album.[37] Pitchfork's Neil Lieberman found some of the ballads tedious and the melodies "cheesy".[27] Citing "Lost Ones" and "Superstar" as highlights, The Village Voice music editor Robert Christgau deemed it the "PC record of the year", featuring exceptionally understated production and skillful rapping but also inconsistent lyrics, average singing, and superfluous skits.[96] He appreciated the "knowledge [and] moral authority" of Hill's perspective and values, although he lamented her appraisal of God on record.[97] In the Los Angeles Times, Soren Baker believed Hill was more effective as a critical rapper than a singer on the more emotional songs, where her voice was "too thin to carry such heavy subject matter".[84]

Accolades

At the end of 1998, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill topped numerous critics polls of the year's best albums,[98] including Rolling Stone,[99] Billboard,[100] Spin,[101] and Time.[102] It was also voted the second best record of the year in the Pazz & Jop, an annual poll of American critics published in The Village Voice.[103] Hill was nominated ten times for the 1999 Grammy Awards, making her the first woman to ever be nominated that many times in one year. She won five Grammys, including awards in the Best New Artist, Best R&B Song, Best Female R&B Vocal Performance, and Best R&B Album categories. The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill also won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year,[104] making it the first hip hop album to ever receive that award. Hill set a new record in the industry, as she also became the first woman to win five Grammys in one night. Hill was the big winner of the night at the 1999 MTV Video Music Awards, taking home four Moonmen, including Best Female Video and Video of the Year, for the music video for her single "Doo Wop (That Thing)", becoming the first hip hop video to win the award.[105] It also earned her nominations at the NAACP Image Awards for Outstanding Female Artist, Outstanding Album, and Outstanding Song ("Doo Wop (That Thing)").[106] At the Billboard Music Awards, the record won in the R&B Album of the Year category, while "Doo Wop" won Best R&B/Urban New Artist Clip,[107] and at the 1999 American Music Awards, Hill won the award for Best New Soul/R&B artist.[76] She also won a Soul Train award and received a nomination for Best International Female Solo Artist at the Brit Awards.[81]

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill has since appeared on a number of lists ranking the greatest albums ever; according to Acclaimed Music, it is the 113th most acclaimed album based on such rankings.[108]

| Publication | Country | Accolade[109] | Year | Rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| About.com | United States | 100 Greatest Hip-Hop Albums[110] | 2008 | 43 | ||

| Best Rap Albums of 1998[111] | 2008 | 1 | ||||

| Associated Press | The 10 Best Albums of the 1990s | 1999 | * | |||

| Blender | 500 CDs You Must Own Before You Die | 2003 | * | |||

| The 100 Greatest American Albums of All time | 2002 | 75 | ||||

| CD Now | The 10 (+5) Essential Records of the 90s | 2002 | * | |||

| Ego trip | Hip Hop's 25 Greatest Albums by Year 1980–98 | 1999 | 4 | |||

| Hip Hop's 25 Greatest Albums by Year 1980–98 | 1999 | 5 | ||||

| Entertainment Weekly | The 100 Best Albums from 1983 to 2008 | 2008 | 2 | |||

| 30 essential albums from the last 30 years[112] | 2020 | * | ||||

| Gear | The 100 Greatest Albums of the Century | 1999 | 88 | |||

| Ink Blot | Best Albums of the 90s | 2000 | 9 | |||

| Kitsap Sun | Top 200 Albums of the Last 40 Years | 2005 | 65 | |||

| NPR | The 150 Greatest Albums Made By Women[113] | 2017 | 2 | |||

| Turning The Tables: The 150 Greatest Albums Made By Women (As Chosen By You)[114] | 2018 | 3 | ||||

| Nude as the News | The 100 Most Compelling Albums of the 90s | 1999 | 40 | |||

| Pause & Play | 10 Albums of the 90's | 2003 | * | |||

| Albums Inducted into a Time Capsule | 2003 | * | ||||

| The 90s Top 100 Essential Albums | 1999 | 7 | ||||

| Pitchfork | The 150 Best Albums of the 1990s[115] | 2022 | 2 | |||

| Robert Dimery | 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[116] | 2005 | * | |||

| Rock and Roll Hall of Fame | 200 Definitive Albums of All Time[117] | 2007 | 55 | |||

| Rolling Stone | 50 Essential Female Albums | 2002 | 32 | |||

| 500 Greatest Albums of All Time | 2020 | 10 | ||||

| The Essential Recordings of the 90s | 1999 | * | ||||

| 100 Best Albums of the Nineties[118] | 2011 | 5 | ||||

| The Source | The Critics Top 100 Black Music Albums of All Time[119] | 2006 | 10 | |||

| Spin | Top 100 (+5) Albums of the Last 20 Years | 2005 | 49 | |||

| Top 90 Albums of the 90s | 1999 | 28 | ||||

| Tom Moon | 1000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die | 2008 | * | |||

| VH1 | The 100 Greatest Albums of R 'N' R | 2001 | 37 | |||

| Vibe | 150 Albums That Define the Vibe Era | 2007 | * | |||

| 51 Albums representing a Generation, a Sound and a Movement | 2004 | * | ||||

| BBC Radio | United Kingdom | Stuart Maconie's Critical List | 1999 | 17 | ||

| Channel 4 | The 100 Greatest Albums | 2005 | * | |||

| Elvis Costello | 500 Albums You Need | 2000 | * | |||

| Gary Mulholland | 261 Greatest Albums Since Punk and Disco | 2006 | * | |||

| The Guardian | 1000 Albums to Hear Before You Die | 2007 | * | |||

| Hip-Hop Connection | The 100 Greatest Rap Albums 1995–2005 | 2005 | 39 | |||

| Metro Times | Top 10 Albums of the 90s | 1999 | 8 | |||

| Mojo | The 100 Greatest Albums of Our Lifetime 1993–2006 | 2006 | 67 | |||

| The Mojo Collection | 2007 | * | ||||

| The New Nation | Top 100 Albums by Black Artists | 2003 | 10 | |||

| Q | 90 Albums of the 90s | 1999 | * | |||

| The Ultimate Music Collection | 2005 | 41 | ||||

| Top 100 Albums Ever[120] | 2003 | 20 | ||||

| The Rough Guide | Soul: 100 Essential CDs | 2000 | * | |||

| Aftenposten | Norway | Top 50 Albums of All Time | 1999 | 48 | ||

| Eggen & Kartvedt | The Guide to the 100 Important Rock Albums | 1999 | * | |||

| Helsingin Sanomat | Finland | 50th Anniversary of Rock | 2004 | 2 | ||

| Musik Express | Germany | The 50 Best Albums of the 90s | 2005 | 23 | ||

| Wiener | Austria | The 100 Best Albums of the 20th Century | 1999 | 100 | ||

| Fnac | France | The 1000 Best Albums of All Time | 2008 | 420 | ||

| Rock & Folk | The Best Albums from 1963 to 1999 | 1999 | * | |||

| Dance de Lux | Spain | The 25 Best Hip-Hop Records | 2001 | 12 | ||

| Rock de Lux | The 150 Best Albums from the 90s | 2000 | 132 | |||

| Juice | Australia | The 100 (+34) Greatest Albums of the 90s | 1999 | 55 | ||

| Babylon | Greece | The 50 Best Albums of the 1990s | 1999 | 45 | ||

| Pure Pop | Mexico | The 50 Best Albums of the 90s | 2000 | 40 | ||

| The Sun | Canada | The Best Albums from 1971 to 2000 | 2001 | * | ||

| (*) designates lists that are unordered. | ||||||

Lawsuit

Though The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill was largely a collaborative work between Hill and a group of musicians known as New Ark (Vada Nobles, Rasheem Pugh, Tejumold Newton, and Johari Newton), there was "label pressure to do the Prince thing," wherein all tracks would be credited as "written and produced by" the artist with little outside help.[17][40] While recording the album, Hill was against the idea of creating documentation defining each musician's role.[17]

In 1998, New Ark filed a 50-page lawsuit against Hill, her management and her record label, stating that Hill "used their songs and production skills, but failed to properly credit them for the work."[121] The musicians claimed to be the primary songwriters on two tracks, and major contributors on several others, though Gordon Williams, the album's mixer and engineer, described the project as a "powerfully personal effort by Hill ... It was definitely her vision."[90] Audio engineer Tony Prendatt, who also worked on the album, defended Hill, with a statement saying "Lauryn's genius is her own".[122] In response to the lawsuit, Hill claimed that New Ark took advantage of her success.[123] New Ark requested partial writing credits and monetary reimbursement.[124] The suit was eventually settled out of court in February 2001 for a reported $5 million.[40][125]

Impact and influence

Music Industry

Following the success of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, Hill rose to international superstardom and established herself as a pioneering woman in hip hop,[126][127] as magazines ranging from Time to Esquire to Teen People vied to place her on their front covers. In 1999, Jet declared her as a "Hip Hop icon".[128] Brandon Tensley writing for Time argued that she achieved "icon status through the strength of her debut solo album alone."[129]

In a February 8, 1999, Time cover-story, Hill was credited for helping fully assimilate hip hop into mainstream music, and became the first hip hop artist to ever appear on the magazine's front cover.[130][131] Along with Brown Sugar by D'Angelo, Erykah Badu's Baduizm, and Maxwell's Urban Hang Suite by Maxwell,[132][133] The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill is considered to be one of the most important and definitive releases in the neo soul music scene.[134] According to Ebony magazine, it brought the neo soul genre to the forefront of popular music,[135] and became the genre's most critically acclaimed and popular album.[34] The Encyclopedia of African American Music (2010), noted that "some tracks are based more in hip hop soul than neo soul, but the record is filled with live musicians and layered harmonies, and therefore it is a trendsetting record that connects modern hip hop, R&B, and classic soul music together, creating groundwork for what followed it in the neo soul genre."[34]

Kyle Anderson of MTV noted that the album "essentially gave birth to the genre now known as neo soul, which means you can trace the lineage of Alicia Keys, Erykah Badu, Jill Scott and dozens of others back to Hill's masterpiece."[136] Music journalist David Opie of Highsnobiety, stated that the album has educated "pretty much everyone who's recorded music since" along with "inspiring both newer artists and hip-hop stalwarts alike."[137] According to Billboard, it "taught a generation about the power of baring your soul through song".[127] AllHipHop noted that Hill "mothered a new breed of soul" with the album.[138]

Chris Mench of Complex, wrote that the album "set a new standard for rap women, and even for rap in general", while adding that "its influence extends far beyond the genre walls of hip-hop. It's hard to imagine the rise of conscious artists like Lupe Fiasco or Kendrick Lamar without her, but it's equally as hard to picture widespread success for minimalist, soulful singers like Adele, Amy Winehouse, and even FKA twigs without Lauryn paving the way."[139] While The Guardian referred to the album as "the high-water mark of the conscious hip-hop movement",[140] as well as a "game-changing cri de coeur", and mentioned that it "channelled some precious learning for a generation or more of young women, black and white alike; one in which a ferociously talented artist preached self-determination and self-respect, self-knowledge and getting one's due. It was foremother to Beyoncé's Lemonade and Janelle Monáe's Dirty Computer".[141]

Tributes and anniversary projects

Marvel Comics released a series of variant comic book covers inspired by influential contemporary rap albums, which included a reimagined Miseducation themed Ms. Marvel comic cover.[142] San Francisco Bay Area music collective UnderCover Presents, formed by Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, released a Miseducation tribute album entitled UnderCover Presents: A Tribute to The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (2017).[143]

In 2018, Hill launched a North American tour to commemorate the album's 20th anniversary.[144] Adele penned a letter referring to the album as her "favorite record of all time", while noting that it represented "an honest representation of love and life", and added "I feel I can relate too but also I know there's elements and levels I never will be able to. Ms. Lauryn Hill was on form in every way possible. Thank you for the record of a lifetime, thank you for your wisdom! Thank you for existing. Happy 20th".[145] American girl group TLC, spoke to Beats 1 about the album's influence, with Rozonda "Chilli" Thomas stating "I mean, she be in the videos sometimes pregnant, and sometimes not. She was doing it at a time where they would probably be like, “wait until you have your baby.” Whereas these days, a female artist — whether you're an actress or whatever — if you're pregnant, you celebrate that from the moment that you decide to share it with the world. She didn't care, she just did it. Her voice — to be able to rap like that and sing like that, she was and is unbelievably talented. There's nobody like Lauryn Hill."[146]

In celebration of the album's 20th anniversary, Billboard interviewed 16 artists who have been inspired by the album, which included Jazmine Sullivan, Maggie Rogers, Rapsody, Normani, Chloe Bailey, Lizzo, Andra Day, Saweetie, Ella Mai, Teyana Taylor, Anne-Marie and more.[147] The album was also the subject of author and journalist Joan Morgan's 2018 book She Begat This: 20 Years of 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill'.[148][149] That same year, Spotify presented the Dear Ms. Hill art installation in Brooklyn, New York which saw fans, including H.E.R. and Kelly Rowland, submit letters about The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, and then used those letters to turn them into paper art.[150] Further, the Spotify podcast Dissect launched their first ever mini series, which examined the album and its impact.[151] Hill also collaborated with Woolrich to design Miseducation inspired pieces for their 'American Soul Since 1830' collection, and starred in the accompanying campaign.[152][153]

Legacy

Rankings and honors

In 2007, the album was placed on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's "200 Definitive Albums of All Time" list.[154] On The Miseducation's fifteenth anniversary in 2014, American rapper Nas reviewed the album for XXL, hailing it as a model for artists of all genres to follow. He also called it "a timeless record, pure music", and said it "represents the time period—a serious moment in Black music, when young artists were taking charge and breaking through doors."[155] In 2015, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for inclusion in the National Recording Registry.[156]

In 2017, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill was among the first batch of albums to preserved in Harvard University's Loeb Music Library.[157] That same year, NPR named it the second greatest album made by a woman.[158] The album has also been included in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American history.[159] While ranking it 314th on their "500 Greatest Albums of All Time", Rolling Stone credited Hill with taking 1970s soul and making it "boom and signify to the hip-hop generation".[160] The magazine's placement of The Miseducation at number 10 on a revised edition in 2020 made it the highest ranking rap album on the list.[161]

Reappraisal

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Christgau's Consumer Guide | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| The Great Rock Discography | 9/10[164] |

| Pitchfork | 9.5/10[28] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Slant Magazine | |

| Sputnikmusic | 4.5/5[166] |

| Tom Hull – on the Web | B+[167] |

| XXL | 5/5[155] |

Jon Caramanica, writing in The Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004), called it "as earnest, unpretentious, and pleasantly sloppy an album as any woman of the hip-hop generation has ever made", and said that, by appealing to a wide spectrum of listeners with hip hop filtered through a "womanist lens", the album propelled Hill to superstardom "of epic proportions" and "the focal point at hip-hop's crossover into the mainstream."[165] Music journalist Peter Shapiro cited it as "the ultimate cross-over album of the hip-hop era."[168]

Legacy

Miseducation remains Hill's only studio album. After its success, the singer shunned her celebrity status and pursued a private life while raising six children, but both personal and professional difficulties followed. As Miami New Times journalist Juliana Accioly explained, "She was reported to have spent years on a spiritual quest while dealing with bipolar disorder. She was sued over songwriting credits. She served a three-month prison sentence in 2013 for tax evasion. She was deemed a diva for wanting to be called 'Ms. Hill' and criticized for her erratic performances." In October 2018, Hill embarked on a concert tour commemorating Miseducation's 20th anniversary. In its anticipation, Accioly reflected on the album in the context of the Me Too movement of recent years: "Against that backdrop, Hill's own descriptions of mistreatment carry validation and support for victims. … For women who came up during Miseducation's zenith, attending Hill's 2018 performance could serve as a measure of how much the world around them has changed — and how many things remain the same. Her crash course on life is still very much relevant: 'It could all be so simple,' but it's not."[169]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Lauryn Hill, except where noted. All tracks are produced by Hill. "Lost Ones" and "To Zion" were co-produced by Che Pope, and "Lost Ones" was additionally produced by Vada Nobles.[170]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Intro" | 0:47 | |

| 2. | "Lost Ones" | 5:33 | |

| 3. | "Ex-Factor" | 5:26 | |

| 4. | "To Zion" (featuring Carlos Santana) | 6:08 | |

| 5. | "Doo Wop (That Thing)" | 5:19 | |

| 6. | "Superstar" |

| 4:56 |

| 7. | "Final Hour" | 4:15 | |

| 8. | "When It Hurts So Bad" | 5:42 | |

| 9. | "I Used to Love Him" (featuring Mary J. Blige) | 5:39 | |

| 10. | "Forgive Them Father" | 5:15 | |

| 11. | "Every Ghetto, Every City" | 5:14 | |

| 12. | "Nothing Even Matters" (featuring D'Angelo) | 5:49 | |

| 13. | "Everything Is Everything" |

| 4:58 |

| 14. | "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" |

| 4:17 |

| 15. | "Can't Take My Eyes Off You" (hidden track) |

| 3:41 |

| 16. | "Tell Him" (hidden track) | 4:38 | |

| Total length: | 77:37 | ||

Personnel

Credits are adapted from the album's liner notes.[170]

Musicians

- Al Anderson – guitar (track: 12)

- Tom Barney – bass (tracks: 11–13)

- Bud Beadle – alto/tenor saxophone, flute (track: 7)

- Robert Browne – guitar (track: 2)

- Rudy Byrd – percussion (tracks: 3, 6, 8)

- Che Pope – drum programming (tracks: 5, 6, 8–10, 12, 13)

- Jared Crawford – live drums (track: 4)

- D'Angelo – Rhodes piano (track: 12)

- DJ Supreme – DJ (track: 5)

- Francis Dunnery – guitar (tracks: 11, 12)

- Paul Fakhourie – bass (track: 3)

- Dean Frasier – saxophone (tracks: 5, 10)

- Loris Holland – keys (tracks: 12, 14); clavinet (track: 11)

- Indigo Quartet – strings (tracks: 5, 13, 14)

- Julian Marley – guitar (track: 10)

- Chris Meredith – bass (tracks: 8, 10, 12)

- Johari Newton – guitar (tracks: 2, 3, 8)

- Tejumold Newton – piano (track: 3)

- Vada Nobles – drum programming (tracks: 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 13)

- Arun Pandian – guitar (track 16 – Tell Him)

- Grace Paradise – harp (tracks: 4, 6, 8)

- James Poyser – bass (tracks: 2, 4, 9); keys (tracks: 3, 5, 6, 12)

- Everol Ray – trumpet (tracks: 5,10)

- Kevin Robinson – trumpet, flugelhorn (track: 7)

- Ronald "Nambo" Robinson – trombone (tracks: 5, 10)

- Matthew Rubano – bass (tracks: 9, 13)

- Carlos Santana – guitar (track: 4)

- Earl Chinna Smith – guitar (tracks: 2,10)

- Andrew Smith – guitar (track: 7)

- Squiddly Ranks – live drums (track: 8)

- John R. Stephens – piano (track: 13)

- Elizabeth Valletti – harp (track: 7)

- Fayyaz Virti – trombone (track: 7)

- Joe Wilson – piano (track: 14)

- Stuart Zender – bass (track: 7)

Production

- Errol Brown – assistant recording engineer (tracks: 2, 10)

- Che Pope – co-producer (tracks: 2, 4)

- Lauryn Hill – producer, executive producer (tracks: 1–16)

- Matt Howe – recorder (track: 7)

- Storm Jefferson – recorder (tracks: 8, 9, 11, 12); mix engineer (track: 8); assistant mix engineer (tracks: 2, 9)

- Ken Johnson – recorder (track: 9); assistant recording engineer (track: 4)

- Vada Nobles – co-producer (track: 2)

- Tony Prendatt – recorder (tracks: 6, 7, 9, 12–14); engineer (track: 14)

- Warren Riker – recorder (tracks: 4, 5, 8, 12); mix engineer (tracks: 2, 9)

- Jamie Seigel – assistant mix engineer (track: 4)

- Greg Thompson – assistant mix engineer (track: 3)

- Neil Tucker – assistant recording engineer (track: 7)

- Chip Verspyck – assistant recording engineer (tracks: 3, 7)

- Brian Vibberts – assistant engineer (tracks: 6, 10, 12)

- Gordon "Commissioner Gordon" Williams – recorder (tracks: 2 – 6, 8 -12); engineer (tracks: 9, 14); mixer (tracks: 2, 4 – 6, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14)

- Johny Wyndrx – recorder (track: 4)

Vocalists

- Lauryn Hill – vocals (tracks: 2–16)

- Mary J. Blige – vocals (track: 9)

- D'angelo – vocals (track: 12)

- Shelley Thunder – vocals (track: 10)

- Kenny Bobien – backing vocals (track: 4)

- Chinah – backing vocals (track: 9)

- Jenni Fujita – backing vocals (track: 5)

- Fundisha Johnson – backing vocals (track: 5)

- Sabrina Johnston – backing vocals (track: 4)

- Jenifer McNeil – backing vocals (track: 9)

- Rasheem Pugh – backing vocals (track: 5)

- Lenesha Randolph – backing vocals (tracks: 4, 5, 9, 13)

- Ramon Rivera – backing vocals (track: 9)

- Earl Robinson – backing vocals (track: 4)

- Andrea Simmons – backing vocals (tracks: 4,9)

- Eddie Stockley – backing vocals (track: 4)

- Ahmed Wallace – backing vocals (tracks: 9,13)

- Tara Watkins – backing vocals (track: 9)

- Rachel Wilson – backing vocals (track: 9)

- Chuck Young – backing vocals (track: 3)

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

Decade-end charts

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[223] | 2× Platinum | 140,000 |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[224] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Belgium (BEA)[225] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[226] | 7× Platinum | 700,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[227] | Platinum | 300,000* |

| Japan (RIAJ)[228] | Million | 1,000,000^ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[229] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[230] | 3× Platinum | 45,000^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[231] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[232] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| Sweden (GLF)[233] | Platinum | 80,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[234] | Platinum | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[235] | 4× Platinum | 1,200,000 |

| United States (RIAA)[71] | Diamond | 10,000,000 |

| Summaries | ||

| Europe (IFPI)[236] | 2× Platinum | 2,000,000* |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

- Billboard Year-End

- List of Billboard 200 number-one albums of 1998

- List of number-one R&B albums of 1998 (U.S.)

- List of number-one R&B albums of 1999 (U.S.)

- List of best-selling albums in the United States

References

Footnotes

- Samuels, Anita M. (August 1, 1998). "Hill Gets Head Start on New Solo Set". Billboard. Vol. 110, no. 31. p. 13.

...the label will ship the album's first official single, 'Doo Wop (That Thing),' to R&B outlets Aug. 10...

- Billboard. December 5, 1998.

- "Lauryn Hill becomes first female rapper to receive a diamond certification". Hip Hop Freaks. February 17, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- "Nicki Minaj Extends Lead As Highest-Selling Female Rapper As Debut Album Reaches New Sales Milestone – ..::That Grape Juice.net::.. – Thirsty?". thatgrapejuice.net. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- "Soul on fire". CBC News. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- Furman & Furman 1999, p. 112.

- Furman & Furman 1999, p. 102; Nickson 1999, p. 132.

- Furman & Furman 1999, pp. 128–129.

- Nickson 1999, p. 132.

- Furman & Furman 1999, p. 106.

- Nickson 1999, p. 133.

- Furman & Furman 1999, p. 157.

- Furman & Furman 1999, p. 138.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 148.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, p. 151.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, pp. 141–142.

- Touré (October 30, 2003). "The Mystery of Lauryn Hill". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 20, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 141.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 149.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 150.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, p. 146.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, pp. 153–154.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 140.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, p. 140.

- Bush, John. "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill – Lauryn Hill". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- Schrodt, Paul (August 19, 2008). "Lauryn Hill: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- Lieberman, Neil. "Lauryn Hill: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 19, 2003. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- Wallace, Carvell (July 10, 2016). "Lauryn Hill: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- Weisbard, Eric (September 1998). "Triumph of the Hill". Spin. Vol. 14, no. 9. pp. 179–80. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- Farley, Christopher John (June 24, 2001). "Neo-Soul On A Roll". Time. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- Reeves, Mosi (September 30, 2010). "Source Material: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Rhapsody. Archived from the original on October 6, 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- "3. Lauryn Hill, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill – The 50 Best R&B Albums of the '90s". Damien Scott, Brendan Frederick, Craig Jenkins, Elena Bergeron, Justin Charity, Ross Scarano, Shannon Marcec of Complex. July 10, 2014. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Havranek, Carrie, 2009, p. 47.

- Price et al., 2010, p. 902.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 143.

- Touré (August 12, 1998). "Lauryn Hill: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- Mulvey, John (September 23, 1998). "Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". NME. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, pp. 154–155.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, pp. 159–160.

- Checkoway, Laura (August 26, 2008). "Inside 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill' (p.3)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 161.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, pp. 108–109.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, p. 148.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, p. 133.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, p. 149.

- Hoye, Jacob, ed. (2003). One Hundred Greatest Albums. Simon & Schuster. p. 95. ISBN 0-7434-4876-6.

- "Lauryn Hill's Miseducation is more than a crossover—it's a beacon". www.avclub.com. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- Jolson-Colburn, Jeffrey (September 2, 1998). "Lauryn Hill Queen of the Music Hill". E! Online. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- "Cardi B Becomes Fifth Female Rapper to Hit No. 1 on Billboard 200 Albums Chart". Billboard. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- Rob, D. J. (April 15, 2018). "Here's The Short List of Female Rappers To Top The Billboard Album Chart …And The LONG List Of Those Who Haven't". Djrobblog.com. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- "Lauryn Hill's 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill' Goes Diamond".

- "Ladies First Quiz: Ariana Grande & 15 No. 1 Female Debut Albums | Billboard". Billboard. January 6, 2017. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- "'Work' Week: Rihanna Tops Hot 100 for Seventh Week, Fifth Harmony Earns First Top 10 Hit". Billboard. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Billboard. April 20, 2002.

- "Ashanti Album, Single Dominate Charts". Billboard. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- "Kanye West, Nicki Minaj Score Big Debuts on Billboard 200". Billboard. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- "Celebrities". Journal Sentinel. Milwaukee. September 11, 1998. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- Archive-Randy-Reiss. "Lauryn Hill's Miseducation Holds Tight At #1". MTV News. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- Billboard. January 30, 1999.

- "R&B/Hip-Hop Albums : Nov 03, 2015 | Billboard Chart Archive". Billboard. November 4, 2015. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- "Eminem, Jay Z, MC Hammer and More: Rap Chart Facts You May Not Know". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- "Every Number 1 rap album in Ireland". www.officialcharts.com. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- Inc, Nielsen Business Media (March 27, 1999). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.

- "TLC Edges Out Eminem, Grammy Winners In Chart Race". MTV News. March 3, 1999. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- "TLC Holds On To Top Of Album Chart". MTV News. March 10, 1999. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- Stevenson, Jane (August 10, 1999). "Molson Amphitheatre, Toronto – Aug 10, 1999". Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- Newman, Melinda (April 20, 2002). "The Beat". Billboard. p. 12. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- Wilson, Natashia (April 16, 2009). "The Miseducation Lauryn Hill: Music Review". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on February 8, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- "10 Iconic Albums From 1998 We're Still Playing". Spotify. December 11, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- Harris, Christopher (April 5, 2021). "Cardi B's 'Invasion of Privacy' breaks another Billboard record". REVOLT. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- "American album certifications – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- "First female rapper to reach RIAA Diamond status". Guinness World Records. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- "CERTIFIED CLASSICS IN COLLABORATION WITH SPOTIFY CELEBRATES 20 YEARS OF THE ICONIC THE MISEDUCATION OF LAURYN HILL ALBUM WITH DEAR MS. HILL & DISSECT MINI SERIES – Sony Music Canada". www.sonymusic.ca. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- "The Selling of 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill'". www.okayplayer.com. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- "20 Years Since Lauryn Hill's Debut, How Much Has Changed?". PAPER. June 29, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 185.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, p. 166.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 184.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 188–189.

- Rees, Dafydd; Crampton, Luke (1999). Rock Stars Encyclopedia (2nd ed.). DK Publishing. p. 463. ISBN 0-7894-4613-8.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 190.

- Browne, David (September 4, 1998). "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- Odell, Michael (September 25, 1998). "Head for the Hill". The Guardian.

- Baker, Soren (August 23, 1998). "Lauryn Hill 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill' Ruffhouse/Columbia". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- Mathur, Paul (October 3, 1998). "Lauryn Hill: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (Columbia)". Melody Maker. Archived from the original on August 13, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- Jones, Bob (December 1998). "Lauryn Hill: The Miseducation Of... (Columbia)". Muzik. No. 43. p. 94.

- Phillips, Dom (November 1998). "Lauryn Hill: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Q. No. 146. Archived from the original on September 30, 1999. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- Br; August 25, on Tensley; Edt, 2018 7:00 Am. "How Lauryn Hill Educated the Music Industry 20 Years Ago". Time. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- Strauss, Neil (February 25, 1999). "5 Grammys to Lauryn Hill; 3 to Madonna". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- Boucher, Geoff (December 19, 2008). "The Legal Tangle of 'Miseducation'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- Powers, Ann (August 23, 1998). "Cross Back Over From Profane to Sacred". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- Hampton, Dream (September 1, 1998). "Educating Lauryn". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- Kot, Greg (August 23, 1998). "Lauryn Hill The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- May 26, XXL StaffPublished; 2015. "Happy Birthday, Lauryn Hill! – XXL". XXL Mag. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Anon. (October 24, 1998). "Succeed". Billboard. p. 99. Retrieved July 25, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Christgau, Robert (November 3, 1998). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- Christgau, Robert (March 2, 1999). "Pazz & Jop 1998: La-Di-Da-Di-Di? Or La-Di-Da-Di-Da?". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- "'The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill' Turns 20". Stereogum. August 24, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- "Rocklist.net....Rolling Stone (USA) Lists Page 2..." www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- Billboard. December 30, 2000.

- "Spin Magazine End Of Year Lists". www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- "Music: The Best Of 1998 Music". Time. December 21, 1998. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- "The 1998 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. New York. March 2, 1999. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- "41st Annual Grammy Awards". Grammy.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- Weingarten, Christopher R. (August 25, 2018). "Flashback: See Lauryn Hill Perform Lush Version of 'Lost Ones' at MTV VMAs". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, p. 183.

- Nickson, Chris, 1999, pp. 182–183.

- "Acclaimed Music". May 2, 2021. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill album accolades". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on December 1, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- Adaso, Henry. "About.com's 100 Greatest Hip-Hop Albums". About.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- Adaso, Henry. "About.com's Best Rap Album's of 1998". About.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- "30 essential albums from the last 30 years". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- "The 150 Greatest Albums Made By Women". NPR. July 24, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- Powers, Ann (April 9, 2018). "Turning The Tables: The 150 Greatest Albums Made By Women (As Chosen By You)". NPR. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- "The 150 Best Albums of the 1990s". Pitchfork. September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (March 23, 2010). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2074-2.

- "The 200 Definitive Albums Of All Time Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame 2007 at EIL.COM, home of Esprit International Limited". eil.com. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- "100 Best Albums of the Nineties: Lauryn Hill, 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- "The Critics Top 100 Black Music Albums of All Time". Trevor Nelson. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- Columnist. "Top 100 Albums Ever". Q. Issue 198. January 2003.

- McLeod, Rod (May 10, 2000). "The reeducation of Lauryn Hill". Salon. Archived from the original on November 30, 2005. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- Inc, Nielsen Business Media (March 6, 1999). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.

- Furman; Leah, Elina. 1999, p. 163.

- "Pras Deposed in Lauryn Hill Lawsuit". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- Perry, Claudia (February 11, 2001). "Lauryn Hill Settles Lawsuit". rollingstone.com. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- Touré (April 1, 2007). Never Drank the Kool-Aid: Essays. Picador. ISBN 978-1-4299-0109-3.

- BlackPressUSA/NNPA (November 28, 2019). "Meet The Pioneering Queens of Hip-Hop". AFRO American Newspapers. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- Company, Johnson Publishing (March 15, 1999). Jet. Johnson Publishing Company.

- Br; August 25, on Tensley; Edt, 2018 7:00 Am. "How Lauryn Hill Educated the Music Industry 20 Years Ago". Time. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- Farley, Christopher John Farley (February 8, 1999). "Music: Hip-Hop Nation: Lauryn Hill". Time. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- Glass, Burton. "Lauryn Hill Deserves It All". Essay Archive. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- Cochrane, Naima (March 26, 2020). "2000: A Soul Odyssey". Billboard. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- "Maxwell Talks Social Media, Making Politically Charged Music & What the Legacy of 'Embrya' is 20 Years Later [Interview]". www.okayplayer.com. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- "Neo-Soul". AllMusic. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- "10 at the Top of Hip-Hop". Ebony. June 1999. p. 59. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- "Lauryn Hill Teaches Everybody With 'Miseducation': Wake-Up Video". MTV. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- "What 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill' Taught Us About Life And Music". Highsnobiety. May 27, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- Watkins (@GrouchyGreg), Grouchy Greg (June 26, 2008). "The Neo-Soul Family Tree". AllHipHop. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- "20 Rappers Who Are Influencing Rap Right Now". Complex. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- "The message: why should hip-hop have to teach us anything?". the Guardian. October 7, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- "Lauryn Hill review – a difficult re-education | Lauryn Hill | The Guardian". amp.theguardian.com. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- "Marvel Comics Pay Homage to Hip-Hop Albums With Variant Covers". Pitchfork. July 14, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- "A Tribute to The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". YBCA. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- "GRAMMY.com". www.grammy.com. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- September 19, Karen Mizoguchi; Pm, 2018 03:45. "Adele Tells Lauryn Hill 'Thank You for Existing' in Honor of 20th Anniversary of Miseducation Album". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "TLC Honor Lauryn Hill's 'Miseducation Of' Album on 20th Anniversary". TLC-Army.com. August 29, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- Feeney, Nolan (June 1, 2018). "The Next Generation of Lauryn Hill: 16 Artists on Their Favorite 'Miseducation' Songs". Billboard. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- "The Best Music Books of 2018". Pitchfork. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- "Joan Morgan on Her New Book and 20 Years of Lauryn Hill's Miseducation". jezebel.com. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- Staff, BrooklynVegan StaffBrooklynVegan. "Lauryn Hill played Fashion Week; Spotify paying tribute to 'Miseducation' in Williamsburg". BrooklynVegan. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- Grant, Shawn (August 24, 2018). "Spotify to Celebrate 20th Anniversary of 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill'". The Source. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- Penrose, Nerisha (July 30, 2018). "Lauryn Hill Sings Your Favorite Breakup Song in Her Woolrich Ad Campaign". ELLE. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- Newbold, Alice. "Why Lauryn Hill Waited Until Now To Front Her First Fashion Campaign". British Vogue. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- "The 200 Definitive Albums Of All Time Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame 2007 at EIL.COM, home of Esprit International Limited". eil.com. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- Nas (August 26, 2013). "Nas Reviews Lauryn Hill's 'The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill' – XXL Issue 150". XXL. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- "National Recording Registry To 'Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive'". Library of Congress. March 25, 2015. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- "9th Wonder Selects 4 Hip-Hop Classics To Be Preserved in Harvard's Library". April 29, 2021. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- N; P; R (July 24, 2017). "The 150 Greatest Albums Made By Women". NPR. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill | National Museum of African American History and Culture". April 29, 2021. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- "Lauryn Hill, 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- "Rolling Stone Lists 'Miseducation of Lauryn Hill' Greatest Rap Album". Okayplayer. September 22, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- Christgau, Robert (2000). "Lauryn Hill: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. Macmillan Publishers. p. 134. ISBN 0312245602. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- Larkin, Colin (2006). "Hill, Lauryn". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 4 (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 290. ISBN 0-19-531373-9.

- Strong, Martin C. (2004). "Lauryn Hill". The Great Rock Discography (7th ed.). Canongate U.S. ISBN 1841956155.

- Caramanica 2004, p. 379.

- Butler, Nick (January 16, 2005). "Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (album review)". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- Hull, Tom (n.d.). "Grade List: Lauryn Hill". Tom Hull – on the Web. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- Shapiro, Peter (2003). Buckley, Peter (ed.). The Rough Guide to Rock (2nd ed.). Rough Guides. p. 400. ISBN 1-85828-457-0.

- Accioly, Juliana (October 5, 2018). "Revisiting Ms. Lauryn Hill's Miseducation in the #MeToo Era". Miami New Times. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (CD). Ruffhouse Records. 1998. CK 69035.

- "Australiancharts.com – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Austriancharts.at – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "Ultratop.be – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Ultratop.be – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Lauryn Hill Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "European Top 100 Albums" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 15, no. 42. October 17, 1998. p. 13 – via World Radio History.

- "Lauryn Hill: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Lescharts.com – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Offiziellecharts.de – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- "Top National Sellers: Greece" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 16, no. 22. May 29, 1999. p. 14 – via World Radio History.

- "Top National Sellers: Ireland" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 16, no. 13. March 27, 1999. p. 12 – via World Radio History.

- "Italiancharts.com – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- "Hits of the World – Japan". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. November 7, 1998. p. 60. Retrieved August 4, 2022 – via Google Books.

- "Charts.nz – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Norwegiancharts.com – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- 6, 1999/40/ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- "Swedishcharts.com – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Swisscharts.com – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Lauryn Hill | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- 10, 1998/115/ "Official R&B Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- "Lauryn Hill Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "Lauryn Hill Chart History (Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- "Lauryn Hill". Billboard. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- "RPM's Top 100 CDs of '98". RPM. December 14, 1998. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- "Eurochart Hot 100 Albums 1998" (PDF). Music & Media. December 19, 1998. p. 8. OCLC 29800226. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Tops De L'annee: Top Albums 1998". SNEP (in French). Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- "1998年 アルバム年間TOP100" [Oricon Year-end Albums Chart of 1998] (in Japanese). Archived from the original on January 8, 2008. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- "Top Selling Albums of 1998". The Official NZ Music Charts. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- "Year list Album (incl. Collections), 1998". Sverigetopplistan (in Swedish). Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- "Lauren Hill | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart.

- "1998 Year-End Chart – Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- "Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums – Year-End 1998". Billboard. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "ARIA Charts – End Of Year Charts – Top 100 Albums 1999". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- "Jahreshitparade 1999". Ö3 Austria. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "1999 – ultratop (Flanders)". Ultratop. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "1999 – ultratop (Wallonia)". Ultratop. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "TOP20.dk © 1999". Hitlisten. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1999". dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Eurochart Top 100 Albums 1999" (PDF). Billboard. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Classement Albums – année 1999" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique (SNEP). Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts (1999)". Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- "Top Selling Albums of 1999". The Official New Zealand Music Chart. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "VG-lista – Topp 40 Album Russetid 1999" (in Norwegian). VG-lista. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "VG-lista – Topp 40 Album Vår 1999" (in Norwegian). VG-lista. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "Year list Album (incl. Collections), 1999". Sverigetopplistan (in Swedish). Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- "{{{artist}}} | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart.

- "1999 Year-End Chart – Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- "Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums – Year-End 1999". Billboard. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "The Top 200 Artist Albums of 2000" (PDF). Chartwatch: 2000 Chart Booklet. Zobbel.de. pp. 39–40. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- "Canada's Top 200 R&B; albums of 2001". Jam!. Archived from the original on September 6, 2004. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- Geoff Mayfield (December 25, 1999). 1999 The Year in Music Totally '90s: Diary of a Decade — The listing of Top Pop Albums of the '90s & Hot 100 Singles of the '90s. Billboard. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2019 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- "Austrian album certifications – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in German). IFPI Austria. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 2002". Ultratop. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- "Canadian album certifications – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Music Canada. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- "French album certifications – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in French). InfoDisc. Retrieved June 21, 2021. Select LAURYN HILL and click OK.

- "Japanese album certifications – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Retrieved February 11, 2010. Select 1999年9月 on the drop-down menu

- "Dutch album certifications – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Retrieved February 11, 2010. Enter The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill in the "Artiest of titel" box.

- "New Zealand album certifications – Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- "IFPI Norsk platebransje Trofeer 1993–2011" (in Norwegian). IFPI Norway. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. p. 950. ISBN 8480486392.

- "Sverigetopplistan – Lauryn Hill" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards (Lauryn Hill; 'The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- "British album certifications – Lauryn Hill – The Misedcuation of Lauryn Hill". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 1999". International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

Bibliography

- Caramanica, Jon (2004). "Lauryn Hill". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Furman, Leah; Furman, Elina (1999). Heart of Soul. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-43588-5.

- Havranek, Carrie (2009). Women Icons of Popular Music: The Rebels, Rockers, and Renegades, Volume 1. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-34084-0.

- Nickson, Chris (1999). Lauryn Hill: She's Got That Thing. St. Martin's Paperbacks. ISBN 0-312-97210-5.

- Price, Emmett G., III; Kernodle, Tammy L.; Maxile, Horace Jr., eds. (2010). Encyclopedia of African American Music, Volume 3. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-34199-1.

Further reading

- Laura Checkoway, "Inside The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill", Rolling Stone, August 26, 2008.

External links

- The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill at Discogs (list of releases)