Tomb Raider (1996 video game)

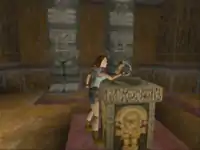

Tomb Raider is a 1996 action-adventure video game developed by Core Design and published by Eidos Interactive. It was first released on the Sega Saturn, followed shortly by versions for MS-DOS and the PlayStation. Later releases came for Mac OS (1999), Pocket PC (2002), N-Gage (2003), iOS (2013) and Android (2015). It is the debut entry in the Tomb Raider media franchise. The game follows archaeologist-adventurer Lara Croft, who is hired by businesswoman Jacqueline Natla to find an artefact called the Scion of Atlantis. Gameplay features Lara navigating levels split into multiple areas and room complexes while fighting enemies and solving puzzles to progress.

| Tomb Raider | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) | |

| Developer(s) | Core Design[lower-alpha 1] |

| Publisher(s) | Eidos Interactive[lower-alpha 2] |

| Programmer(s) | Paul Douglas |

| Artist(s) | Toby Gard |

| Writer(s) | Vicky Arnold |

| Composer(s) | Nathan McCree |

| Series | Tomb Raider |

| Platform(s) | Sega Saturn, MS-DOS, PlayStation, Mac OS, N-Gage, Pocket PC, iOS, Android |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The initial concept was created by Toby Gard, who is credited as Lara's creator and worked as lead artist on the project. Production began in 1994 and took 18 months, with a budget of £440,000. The character of Lara was based on several influences, including Tank Girl, Indiana Jones and Hard Boiled. The 3D grid-based level design, innovative for its time, was inspired by the structure of Egyptian tombs. The music was composed by Nathan McCree, who took inspiration from English classical music. Originally announced in 1995, the title went on to receive extensive press attention and heavy promotion from Eidos Interactive.

Reception of the game was very positive, with praise for its innovative 3D graphics, controls, and gameplay, and it went on to win several industry awards. The game is one of the best-selling video games for the PlayStation, with seven million units sold worldwide, and it remained the best-selling title in the Tomb Raider franchise until the release of the 2013 reboot. Lara Croft herself became a cultural icon, rising to prominence as one of gaming's most recognisable characters. Following the game's success, numerous sequels were released, beginning with Tomb Raider II in 1997. A remake set in a new continuity, Tomb Raider: Anniversary, was developed by Crystal Dynamics and released in 2007.

Gameplay

Tomb Raider is an action-adventure video game in which the player assumes the role of archaeologist-adventurer Lara Croft, who navigates through a series of ancient ruins and tombs in search of an ancient artefact.[8][9] The game is split into four zones: Peru, Greece, Egypt and the lost continent of Atlantis. A training level set in Lara's home of Croft Manor can be accessed from the start menu.[10] The game is presented in third person perspective. Lara is always visible, and the camera follows the action by focusing on Lara's shoulders by default, but the player can take manual control of the camera to get a better look at an area.[8] The game automatically switches to a different camera view at key points, either to give the player a wider look at a new area or to add a cinematic effect.[11] In the Sega Saturn and PlayStation versions, players save their progress in a level using Save Crystals, while in the PC versions the player can save at any point.[12] If Lara is killed, the player must restart from a previous save.[13]

The object of Tomb Raider is to guide Lara through a series of tombs and other locations in search of treasures and artefacts. On the way, she must kill dangerous animals and creatures while collecting objects and solving puzzles.[8] The emphasis lies on exploring, solving puzzles, and navigating Lara's surroundings to complete each level.[11][14] Movement in the game is varied and allows for complex interactions with the environment. In addition to standard movement using tank controls, Lara can walk, jump over gaps, shimmy along ledges, roll, and swim through bodies of water.[13][12][15] Certain button combinations allow Lara to either perform a handstand from a hanging position or execute a swandive.[10]

Lara has two basic stances: one with weapons drawn and one with her hands-free. When her weapons are drawn, she automatically locks on to any nearby targets. Locking onto nearby targets prevents her from performing other actions which require her hands, such as grabbing onto ledges to prevent falling. By default, she carries two pistols with infinite ammo.[11] Additional weapons include a shotgun, dual magnums, and dual Uzis.[10] A general action button is used to perform a wide range of movements, such as picking up items, pulling switches, firing guns, pushing or pulling blocks, and grabbing onto ledges. Items to pick up include ammo, small and large medi-packs, keys, and artefacts required to complete a stage. Any item that is collected is held onto in Lara's inventory until it is used.[13] Throughout each stage, one or more secrets may be located. Discovering these secrets is optional, and when the player finds one a tune plays. The locations of these secrets vary in difficulty to reach. The player is usually rewarded with extra items.[10]

Plot

Archaeologist-adventurer Lara Croft is approached by a mercenary named Larson, who is working for businesswoman Jacqueline Natla. Natla hires Lara to acquire the Scion, a mysterious artefact buried in the tomb of Qualopec within the mountains of Peru. After recovering the Scion from Qualopec's tomb, Lara is ambushed by Larson, who reveals after his defeat that she is holding merely a piece of the artefact, and Natla has sent rival treasure hunter Pierre DuPont to retrieve the other pieces. Breaking into Natla's offices to find out Pierre's whereabouts, Lara discovers a medieval monk's diary, and learns that the Scion is a powerful artefact composed of three pieces, which were divided between the three rulers of the ancient continent of Atlantis, and one of these pieces is buried alongside former Atlantean ruler Tihocan, beneath an ancient monastery, St. Francis' Folly, in Greece.

Navigating the monastery, and following several firefights with Pierre, Lara locates the tomb of Tihocan, where she finally kills Pierre and recovers the second piece of the Scion he had taken. From a mural, she learns that Tihocan unsuccessfully tried to resurrect Atlantis after a catastrophe struck the original continent. After combining both pieces of the Scion, Lara is shown a vision that reveals the third and final piece of the Scion was hidden in Egypt after the third Atlantean ruler, a traitor who used the artefact to create a breed of monsters, was captured and imprisoned by Tihocan and Qualopec. Making her way through Egypt to the lost city of Khamoon, Lara kills Larson and recovers the third Scion piece.

Emerging from the caves, Lara is ambushed by Natla and her three henchmen, who take the Scion. Lara escapes and stows away aboard Natla's yacht, which takes her to a volcanic island holding an Atlantean pyramid filled with monsters. After dispatching Natla's henchmen and making her way through the pyramid, Lara finds the Scion and sees the rest of the vision, revealing Natla to be the betrayer. Lara faces Natla, who reveals that she intends to use her army to push forward humanity's evolution, as she believes both Atlantis and current civilisation are too soft to withstand disaster. Lara decides to destroy the Scion, and Natla's attempt to stop her sends her into a crevasse. After fighting a large legless monster, Lara shoots the Scion, setting off a chain reaction that begins to destroy the pyramid. Lara kills a winged Natla and escapes the exploding island.

Development

The initial concept for Tomb Raider was created by Toby Gard, who worked for Core Design, a game development studio based in Derby, England, that had established itself developing titles for home computers and Sega consoles.[16][17][18] It was proposed by Gard to company head Jeremy Heath-Smith during a 1994 brainstorming session for game concepts for then-upcoming PlayStation console. The entire staff approved, and Heath-Smith gave Gard permission to start the project once he finished work on BC Racers for the Sega CD.[16] The game concept was created before anything else, with the main hooks being its cinematic presentation and being a 3D character-driven experience.[19][20]

The initial team was Gard and Paul Douglas who worked on design and pre-production for six months, before the team expanded to six people including programmers Gavin Rummery and Jason Gosling, and level designers/artists Neal Boyd and Heather Gibson.[16][19] The team wanted to mix the adventuring style of Ultima Underworld and the 3D characters shown off in Virtua Fighter.[20] The development budget for the game at the time was approximately £440,000.[21] The production atmosphere was fairly informal.[18] Development began in 1994 and lasted eighteen months.[17][22] The team endured excessive overtime and crunch during the last stages.[18] During production, Core Design was sold to CentreGold, which in turn was purchased by Eidos Interactive in May 1996, who became publisher for the title.[18][21][23]

When Gard first presented the idea for the game, the concept art featured a male lead who strongly resembled Indiana Jones. Heath-Smith asked for a change for legal reasons.[22][24][25][26] When Gard created the initial design document, he decided to give the player a choice of genders and created a female adventurer alongside the male character. Once he realized creating and animating two playable characters would require double the design work, he decided to slim back down to one.[25] The female character, originally named Laura Cruz, was his favorite, so he discarded the male character before development work began.[21][22][25][27][28] After Eidos became the game's publisher, they unsuccessfully lobbied for a selectable male lead.[21] Speaking about his approach to the concept, Gard noted that he deliberately went against publisher trends when designing both the character and the gameplay.[27] Laura went through several changes before the developers settled on the final version, including a name change to Lara Croft after Eidos executives in America objected to the original name.[24][29] The inspirations for the character of Lara Croft included the character Tank Girl, the Indiana Jones series' titular lead, and the John Woo film Hard Boiled.[20] Lara's notably exaggerated physical proportions were a deliberate choice by Gard, as he wanted a caricatured personification of women who could be an action icon for the younger generation.[20][22][30] Lara's movements were hand-animated and coordinated rather than created using motion capture. The reason for this was that the team wanted uniformity in her movement, which was not possible with motion capture technology of the time.[28]

From the game's earliest stages, the team wanted the title to involve tombs and pyramids.[10] In the early story draft, Lara would be confronted by a rival group called the "Chaos Raiders". During the Greece levels, Lara and Pierre were to have been less hostile rivals, helping each other with puzzles in the first level. Larson evolved from an Afrikaans character called Lars Kruger, who shared a similar role in the original plot.[21] The script itself was written by Vicky Arnold, who joined in 1995 and would work on later Tomb Raider titles.[21][31] Gard and Douglas created the basic story draft alongside the initial game design, then Arnold turned it into a script after joining the project.[21] It was Arnold's job to write the dialogue, and create a cohesive narrative around the locations selected by the team members. While Lara's character design and Gard's initial concept were present, much of the additional detail was worked out by Arnold.[31]

The team kept the project deliberately simple and comparatively modest in scope.[30] The platforming design drew extensively from Prince of Persia, with the Doppelgänger enemy during the Atlantis section being an homage to the Shadow Prince from that game.[21] The high number of animal enemies was meant to ground players in the world before the more fantastical elements appeared, in addition to being easier to animate and program than human enemies. The staff were also uncomfortable with Lara killing that many humans.[30] The initial concept gave combat prominence, but as production began the focus shifted to platforming and puzzle-solving. A plan that made it into the final product was using enemy placement to shift the atmosphere from pure action-adventure to a horror-like tone.[21] The team consciously set the story in real archaeological locations representing several cultures. Boyd and Gibson immersed themselves in literature and history about each culture for the first three areas, respectively inspired by the Inca Empire, Classical Greece and Ancient Egypt.[32] The Greece levels were put in after planned levels in Angkor Wat, Cambodia were dropped.[21] The Croft Manor training level was built by Gard over a weekend.[10] Its design was based on pictures of Georgian manor houses taken from an unspecified reference book.[21]

Design and platforms

The title was developed for Sega Saturn, MS-DOS personal computers (PC), and PlayStation,[12] with all three versions in development simultaneously.[21] Gosling led programming for the Saturn version.[25] Douglas described the game code for each title as identical, with an additional layer of specific coding to tailor the game for each platform.[21] While Sony Europe approved the game early on, making Tomb Raider one of the earliest approved third-party products for the PlayStation, Sony America initially rejected the game's concept and asked for more and better content.[21][22] Douglas blamed the response on Core Design submitting Tomb Raider too early in production.[21] In response the development team made several changes to the game design documentation and produced a version on Sony hardware which would lead to worldwide approval by Sony.[22][26] For the Saturn version, Sega negotiated a timed exclusivity deal in Europe, meaning the Saturn version was released in that region ahead of other versions.[21] Core Design and Sega made the deal during the last few months of development, so the team had to finish up the Saturn version six weeks earlier than they had planned, forcing them to work even longer hours.[16]

Following the release of the Saturn version, a number of bugs were discovered that affected all versions of the game; because of the timed exclusivity, the development team fixed these bugs for the PlayStation and PC versions.[25] Two notable surviving bugs in all versions were the "corner bug", which allowed players to scale architecture by jumping repeatedly against a corner;[21] and a bug which caused the game to not recognise the collection of a secret in the final level.[10] In 1997 Core Design opened negotiations with Nintendo to release a Nintendo 64 version of the game and started work on the port in anticipation of the negotiations being successful.[33] The planning took place between 1996 and 1997, with Douglas wanting to redesign the game mechanics to incorporate the platform's analogue stick controls.[21] The team never received Nintendo 64 development kits,[21] and the port was scrapped when Sony finalised a deal to keep subsequent Tomb Raider games exclusive to PlayStation until the year 2000.[12][21]

A third-person 3D action-adventure like Tomb Raider was unprecedented at the time, and the development team took several months to find a way to make Gard's vision for the game work on the hardware of the time, in particular getting the player character to interact with freeform environments. Tomb Raider used a custom-built game engine, as did many games of the era. The engine was designed and built by Douglas with assistance from Rummery.[21][25] Rummery created the level editor, which allowed for "seamless" creation of levels.[16] According to Rummery, the decision to build the game levels on a grid was the key breakthrough in making the game possible.[34] It is Core Design's contention that, prior to the development of Tomb Raider, they were "struggling somewhat" with 32-bit development.[35][36]

The level editor program was designed so that developers could make rapid adjustments to specific areas with ease.[21][28] Another noted aspect was the multi-layered levels, as compared to equivalent 3D action-adventure games of the time which were mostly limited to a flat-floor system with little verticality.[28] The interlinking room design was inspired by Egyptian multi-roomed tombs, particularly the tomb of Tutankhamun.[22] The grid-based pattern was a necessity due to the d-pad-based tank controls and the Saturn's quad polygon-based rendering technology.[21] Levels were first designed using a wireframe construction, with each area at this stage having only links to other areas of a level and walls. The team then added architecture and gameplay elements like traps and enemies, then implemented the different lighting values.[32] Due to time and technical limitations, planned outdoor areas had to be cut.[27]

The choice of a third-person perspective was influenced by the team's opinion that the game type was under-represented when compared to first-person shooters such as Doom. The third-person view meant multiple elements were difficult to implement, including the character and camera control.[28] The camera had four pre-set angles, which seamlessly switched depending on the character's position and the level progress. For standard navigation and combat, the camera was fixed on a particular point and oriented around Lara while focusing on that object.[32] Lara's twin pistol set-up was in place from the early prototypes.[31] The aiming system was designed so that each gun arm had an aiming axis, with a shared "sweetspot" where both guns fired at the same target. For underwater environments, the effects were created using gouraud shading to create real-time ripple and lighting effects.[32]

Audio

The music for Tomb Raider was composed by Nathan McCree, who at the time was an in-house composer for Core Design.[37] The main inspiration behind the score for McCree was English Classical music.[38] This approach was directly influenced by his conversations with Gard about Lara's character. Based on this, he kept the main theme simple and melodic.[37] The main theme used a four-note motif, which continues to appear through the series.[37][39] The piece "Where The Depths Unfold", used when Lara is swimming underwater, was a choral work.[37][38] They did not have the space or budget for live music recording, which was challenging for McCree as he needed to create the whole thing using synthesisers. To make the choir sound realistic, he inserted recordings of himself breathing at the right points so it sounded like an actual choir.[37] For each track, McCree got a basic description of where the music would be used, then was left to create it. There was no time for rewrites, so each track was included in the game as first composed.[38]

Unlike most other games of the time, there was not a musical track playing constantly throughout the game; instead, limited musical cues would play only during specially-selected moments to produce a dramatic effect.[40] For the majority of the game, the only audio heard is action-based effects, atmospheric sounds, and Lara's own grunts and sighs, all of which were enhanced because they did not have to compete with music. According to McCree, the game was scored this way because he was allotted very little time for the job, forcing him to quickly write pieces without any thought to where they would go in the game. When the soundtrack was finally applied, the developers found that the tunes worked best when applied to specific places.[34] The symphonic sounds were created using Roland Corporation's Orchestral Expansion board for their JV series keyboards.[41]

English voice actress Shelley Blond provided the voice of Lara. She was given the job after her agent called and had her record some audition lines onto tape. She felt under a lot of pressure at the time, as Core Design had spent three months searching for the right voice.[42] She recalled: "I was asked to perform her voice in a very plain non-emotive manner and in a 'female Bond' type of way. I would have added more inflection, tone and emotion to my voice but they wanted to keep it how they felt it should sound, which was quite right. My job was to bring their character to life".[25]

According to Blond, she spent four to five hours recording the voice for Lara including the grunts, cries and other effort and death sounds.[42] A different account attributes these sounds to Gibson, Core Design's PR Manager Suzie Hamilton, and sound designer Martin Iveson whose voice pitch was made higher.[10] Blond would not return for any subsequent entries.[12] In a 2011 interview Blond stated that her departure was due to disagreeing with "some things" within Core Design and Eidos,[42] but five years later she said that she was asked to reprise her role but had to decline due to other commitments.[25] She gave permission for her effort voice work to be reused while the character's dialogue would be voiced by Judith Gibbins.[12][25]

Release and versions

Tomb Raider was first confirmed in 1995, although details were kept scarce by the developers.[23] There was little attention from the press until a demo was run at the 1996 Electronic Entertainment Expo, causing the press and public to pay more attention.[18] There was a huge amount of publicity, much of which did not involve the Core Design team at all, which prompted mixed feelings.[16][18] While the scale of the game's eventual popularity was not in the team's minds, its strong reception at gaming events hinted that it would be a success.[16] To help promote the game, Eidos hired models to portray Lara Croft at trade events. They first hired Natalie Cook, but apparently due to her unsuitability with Eidos's cross-media plans for the character, she was replaced with Rhona Mitra in 1997.[12][19] Mitra served as Lara's model until 1998.[12]

The game was first released for Saturn in Europe on 25 October 1996.[43] In North America, the Saturn, PlayStation and MS-DOS versions were released simultaneously on 14 November.[44] In Europe, the PlayStation and MS-DOS versions were released on 22 November.[43][45] Future PC patches allowed the game to work on Windows 95.[6] The PC version was released on Steam on 29 November 2012.[46] The PlayStation and Saturn versions were also published in Japan in 1997 by Victor Interactive Software under the name Tomb Raiders. The Saturn version was released on 14 January, while the PlayStation version came on 14 February.[5][6] The PlayStation version was re-released for the PlayStation Network in North America in August 2009, and in Europe in August 2010.[47] An attempt was made by Realtech VR to remaster the first three Tomb Raider titles for Windows, but due to not having asked permission from then-franchise owner Square Enix first, the project was cancelled.[48]

In 1997, four new levels were released in an expansion pack for the Windows version, known under the title Tomb Raider: Unfinished Business. The expansion pack also came with promotional materials for the game's sequel Tomb Raider II.[49] In 1998, the levels were made available as downloadable content for the Windows release, and a budget version was released on 20 March containing both the original game and the additional levels under the title Tomb Raider Gold.[50][51] Production on these new levels was led by Phil Campbell, a newcomer who was transferred to Core Design after another project was cancelled.[52][53] The two new areas were dubbed "Unfinished Business", set within the ruins of the Atlantean pyramid; and "Shadow of the Cat", which saw Lara exploring a temple in Egypt dedicated to the goddess Bastet.[51] "Unfinished Business" was intended as an alternate, more difficult finale to the game featuring more mutant enemies and a focus on complex platforming.[54] The concept for "Shadow of the Cat" was born from a cat statue used in the Khamoon level, with the levels being themed after a cat's nine lives.[55] Due to licensing issues, several later re-releases excluded the Gold content.[56]

The game was released for Mac OS on 16 March 1999. It was ported to the platform by Aspyr and based on Tomb Raider Gold.[1] A port to the Pocket PC was published by Handango in July 2002.[2][7] It was released on the N-Gage in October 2003.[57] Both ports were developed by Ideaworks3D.[2][3] Tomb Raider was ported to iOS devices, developed and published by Square Enix. The port was released on 17 December 2013, and includes the additional levels of the Gold release.[4] This version was released on Android devices in April 2015.[58]

Nude Raider

An infamous part of Tomb Raider's history is a fan-made software patch dubbed Nude Raider. The patch, when added to an existing PC copy of a Tomb Raider game, caused Lara to appear naked.[59] In 1999, Core Design considered taking legal action against websites that hosted nude pictures of Lara Croft, stating that "we have a large number of young fans and we don't want them stumbling across the pictures when they do a general search for Tomb Raider".[59] Eidos sent cease and desist letters to the owners of the "nuderaider.com" URL that hosted the patch to enforce its copyright of Tomb Raider. Sites depicting nude images of Lara Croft have been sent cease and desist notices and shut down,[60] and Eidos Interactive was awarded the rights to the Nude Raider domain name.[61] A rumor stated that the game has a cheat code for Lara's nudity. Management did suggest adding it to developers, but they refused.[62] As a response to the controversy, Core Design included a secret code in the sequel; allegedly a similar nude code, it in fact blows Lara up.[62]

Reception

| Aggregator | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iOS | PC | PS | Saturn | |

| GameRankings | N/A | 92%[63] | 90%[64] | 87%[65] |

| Metacritic | 55/100[66] | N/A | 91/100[67] | N/A |

| Publication | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iOS | PC | PS | Saturn | |

| CVG | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Edge | N/A | 9/10[69] | 9/10[69] | N/A |

| EGM | N/A | N/A | 9.125/10[70] | N/A |

| Famitsu | N/A | N/A | 24/40[71] | 31/40[72] |

| GameRevolution | N/A | A[73] | A[74] | A−[74] |

| GamesMaster | N/A | N/A | N/A | 95%[75] |

| GameSpot | N/A | 8.5/10[76] | 8.5/10[77] | 7.9/10[78] |

| GameZone | N/A | 7/10[79] | N/A | N/A |

| IGN | N/A | N/A | 9.3/10[80] | N/A |

| Next Generation | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| TouchArcade | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Sega Saturn Magazine | N/A | N/A | N/A | 92%[83] |

Upon its release in 1996, the game was widely praised by video game magazines for its variety and depth of control,[77][78][81][83][84] revolutionary graphics,[70][77][81][84] intriguing environments,[70][77][81][83] and use of occasional combat to maintain an atmosphere of tension.[78][81][83][85] Ryan MacDonald of GameSpot described the game having a puzzle solving from Resident Evil, the gory action of Loaded, and the ability to have a 360-degree freedom in the gameplay.[78] The game tied with the Saturn version of Street Fighter Alpha 2 for Electronic Gaming Monthly's "Game of the Month", with their review team saying it stood out from other titles and was the PlayStation's best release at the time.[70] Next Generation called it "a thought-provoking, riveting action-adventure easily on par in intensity with any of Hollywood's finest efforts", citing it as a landmark title and potential trend setter for that console generation.[81]

Some critics rated the PlayStation version better than the Saturn version. MacDonald wrote that its graphics were sharper[78] and GamePro scored it half a point higher than the Saturn version in every category despite noting the former's "solid showing".[85] However, Next Generation said that it would not bother to review the PlayStation version because the differences between it and the Saturn version were negligible.[81] Similarly, Electronic Gaming Monthly only reviewed the PlayStation version, and stated in a feature on the game that both versions were playable and enjoyable, while also having identical graphics.[70] A retrospective analysis of the game by Digital Foundry referred to the Saturn version as the least enjoyable versions due to lower frame rate and poorer audio compared to other versions.[6] Next Generation reviewed the PC version of Tomb Raider Gold, rated it three stars out of five, and wrote that it was a suitable purchase for series newcomers, with old players being more likely to download the levels from the game website.[86]

Tomb Raider was Computer Games Strategy Plus's 1996 overall game of the year and won the magazine's award for the year's best "3D Action" game as well.[87] It was a finalist for CNET Gamecenter's 1996 "Best Action Game" award, which went to Quake.[88] Electronic Gaming Monthly named Tomb Raider a runner-up for both "PlayStation Game of the Year" (behind Tekken 2) and "Saturn Game of the Year" (behind Dragon Force), commenting that both versions had been designed to take optimum advantage of each console's capabilities. They named it runner-up for both "Action Game of the Year" (behind Die Hard Trilogy) and "Adventure Game of the Year" (behind Super Mario 64), as well as "Game of the Year" (again behind Super Mario 64).[89] It won "Best Animation" in the 1996 Spotlight Awards.[90]

Less than a year after its release, Electronic Gaming Monthly ranked the PlayStation version of Tomb Raider the 54th-best console video game of all time, particularly citing its vast and compelling areas to explore.[91] In 1998, PC Gamer declared it the 47th-best computer game released, and the editors called it "tremendous fun to play and a legitimate piece of post-modern gaming history".[92] In 2001 Game Informer ranked it the 86th-best game ever made. They praised it for Lara's appeal to gamers and non-gamers alike.[93]

Sales and accolades

At release, Tomb Raider topped the British charts a record three times,[12] and contributed substantially to the success of the PlayStation.[35] In the previous year, Eidos Interactive had recorded a nearly $2.6 million pre-tax loss. The success of the game turned this loss into a $14.5 million profit in a year.[94] As one of the top-selling games of the PlayStation console, it was one of the first to be released on PlayStation's 'Platinum' series, and its success made Tomb Raider II the most anticipated game of 1997.[95] By 1997, 2.5 million units had been sold worldwide.[96]

In August 1998, the game's computer version received a "Platinum" sales award from the Verband der Unterhaltungssoftware Deutschland (VUD), while its PlayStation release took "Gold".[97] These prizes indicate sales of 200,000 and 100,000 units, respectively, across Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.[98] During the first three months of 1997, Tomb Raider was the ninth-best-selling console game in the United States, with sales of 143,000 units. This made it the country's highest-selling PlayStation title for the period.[99] Tomb Raider sold over 7 million copies worldwide.[100] Tomb Raider, along with its successor, Tomb Raider II, were the two best-selling games in the franchise prior to the 2013 reboot.[101][102]

In 1999, Next Generation listed Tomb Raider as number 22 on its "Top 50 Games of All Time", commenting that the level design and art direction enabled a real feeling of exploration and accomplishment.[103] In 2001, GameSpot listed Tomb Raider on its "15 Most Influential Games of All Time", saying it served as a template for many 3D action-adventure games that would follow and helped drive the market for 3D accelerator cards for PCs.[104] In 2004, the Official UK PlayStation Magazine chose Tomb Raider as the fourth-best game of all time.[105]

It won a multitude of Game of the Year awards from leading industry publications.[95] In 1998, Tomb Raider won the Origins Award for Best Action Computer Game of 1997.[106] In 1999, Toby Gard and Paul Douglas won the Berners-Lee Interactive BAFTA Award for best contribution to the industry for their work creating the franchise.[107] In 2018, The Strong National Museum of Play inducted Tomb Raider to its World Video Game Hall of Fame.[108]

Legacy

The sequel to the game, Tomb Raider II, was in the concept stage as production of Tomb Raider was wrapping up.[17] Under pressure from Eidos Interactive, Core Design would develop a new Tomb Raider annually between 1997 and 2000, putting considerable strain on the team. Their struggles culminated in the troubled development of Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness for PlayStation 2. Releasing to poor critical reception and lackluster sales, Eidos Interactive transferred the franchise to another development studio they owned, Crystal Dynamics, who would reboot the series in 2006 with Tomb Raider: Legend.[22][26][34]

Following the release of Tomb Raider, Lara Croft herself became a gaming icon, seeing unprecedented media cross promotion. These included commercials for cars and foodstuffs, an appearance on the cover of The Face, and requests for sponsorship from outside companies.[12][19][22] The level of sophistication Tomb Raider reached by combining state-of-the-art graphics, an atmospheric soundtrack, and a cinematic approach to gameplay was at the time unprecedented.[12][35][109]

While Gard enjoyed working at Core Design, he wished to have greater creative control, and disliked Eidos's treatment of Lara Croft in promotional material, which focused on her sexuality at the expense of her in-game characterisation. Gard and Douglas left Core Design in 1997 to found their own studio, Confounding Factor.[22][30] This prompted mixed feelings from remaining Core Design staff, who were already at work on the next title in the series.[16] Speaking in 2004, Gard said he would have liked to produce a sequel, but noted that Lara had changed from his original concepts for her, leaving him unsure of how he would handle her.[27] Gard would eventually return to the franchise with Tomb Raider: Legend.[16][24]

After the release of Legend, Crystal Dynamics created a remake of Tomb Raider using the Legend engine and continuity. Gard acted as one of the story designers, fleshing out both the main narrative and Lara's characterisation.[22][110] The remake was co-developed by Crystal Dynamics and Buzz Monkey Software.[111] Titled Tomb Raider: Anniversary, the game released worldwide in 2007 for PlayStation 2, Windows, PlayStation Portable, Xbox 360 and Wii.[112][113][114]

Fan interest in the game has continued since its original release. In 2016, developer Timur "XProger" Gagiev began work on OpenLara, an open source port of the original Tomb Raider engine. The further development of this project enabled Tomb Raider to be ported to many modern and legacy systems, such as the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer, the Xbox, iPhone, and the Nintendo 3DS. In January 2022, a version for the Game Boy Advance was released, which attracted attention from several media outlets.[115][116][117]

Notes

References

- "Tomb Raider Gold Is Released For The Macintosh". Aspyr. 16 March 1999. Archived from the original on 1 October 1999. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Tomb Raider On Pocket PC Announced". Tomb Raider Chronicles (fan site). 2002. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "IDeaWorks3D - Works". Ideaworks3D. Archived from the original on 1 July 2006. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Welsh, Chris (17 December 2013). "Original 'Tomb Raider' launches on iOS for 99 cents". The Verge. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- 電撃スパイク『トゥームレイダー: アニバーサリー』製品情報. Dengeki Online. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Digital Foundry (13 November 2016). "DF Retro: Tomb Raider Analysed on PS1/Saturn/DOS/Win95". YouTube. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Play Pocket Tomb Raider". GameSpot. 11 June 2002. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Tomb Raiders: Lara Croft and the Temples of Doom" (PDF). Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 86. Ziff Davis. September 1996. pp. 88–89.

- Cope, Jamie (December 1996). "Tomb Raider: Like shooting gorillas in a barrel". Game Revolution. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- Daujam, Mathieu; Price, James (11 April 2006). "Previous Adventures". Lara Croft Tomb Raider Legend Complete Guide. Piggyback Interactive. pp. 174–177. ISBN 1-9035-1181-X.

- Bright, Rob (August 1996). "Bikini Girls with Machine Guns". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 10. Emap International Limited. pp. 58–61.

- GameTrailers (17 February 2013). Tomb Raider Retrospective Part One. YouTube (Video). Archived from the original on 19 December 2021.

- Core Design (14 November 1996). Tomb Raider Instruction Booklet (PlayStation). Eidos Interactive.

- "Tomb Raider: Indiana Jane and the Temples of Doom" (PDF). Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 89. Ziff Davis. December 1996. pp. 226–7.

- Todd, Hamish (1 March 2013). "Untold Riches: The Intricate Platforming of Tomb Raider". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- Yin-Poole, Wesley (27 October 2016). "20 years on, the Tomb Raider story told by the people who were there". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- Boyer, Crispin (September 1997). "Straight to the Core... (interview with Andrew Thompson)". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 98. pp. 94–96.

- Moss, Richard (31 March 2015). ""It felt like robbery": Tomb Raider and the fall of Core Design". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Sawyer, Miranda (June 1997). "Lara hit in The Face: Article by Miranda Sawyer". The Croft Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- Gard, Toby (28 June 2001). "Q&A: The man who made Lara". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 December 2002. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- "Tomb Raider Q&A with Paul Douglas". Core Design Fansite. 2 April 2020. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Gard, Toby; Smith, Jeremy Heath; Livingstone, Ian (interviews); Hawes, Keeley (narrator) (2007). Unlock the Past: A Retrospective Tomb Raider Documentary (Tomb Raider Anniversary Bonus DVD). Eidos Interactive / GameTap. Also known as Ten Years of Tomb Raider: A GameTap Retrospective

- "IP Profile: Tomb Raider". Develop. 14 November 2008. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- Howson, Greg (18 April 2006). "Lara's Creator Speaks". London: Guardian Unlimited. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- Thorpe, Nick; Jones, Darran (December 2016). "Creating Tomb Raider". Retro Gamer. No. 163. Future Publishing. pp. 18–24.

- Wainwright, Lauren (4 November 2011). "The Redemption of Lara Croft". IGN. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- "An Interview with Toby Gard". Game Informer. No. 137. GameSpot. August 2004.

- "The Making of Tomb Raider". Tomb Raider: Official Game Secrets. Prima Games. December 1996. ISBN 0-7615-0931-3. Transcript

- Magnus Anderson and Rebecca Levine (2012). Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Video Games Conquered the World. Aurum Entertainment. ISBN 978-1845137045.

- Jenkins, David (23 October 1998). "Interview with Toby Gard". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- "An Interview With Vicky Arnold". GameSpot. 1998. Archived from the original on 1 December 1998. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Cover Story: tomb Raider". Mean Machines Sega. EMAP (46): 16–21. August 1996.

- "In the Studio". Next Generation. No. 30. Imagine Media. June 1997. p. 19.

- Thorpe, Nick; Jones, Darran (December 2016). "20 Years of an Icon: Tomb Raider". Retro Gamer. Future Publishing (163): 16–29.

- Blache, Fabian; Fielder, Lauren (31 October 2000). "GameSpot's History of Tomb Raider". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- "The Most Popular Woman in the World!". Next Generation. No. 36. Imagine Media. December 1997. p. 9.

- Greening, Chris (7 December 2014). "Nathan McCree Interview: 21 Years of Pioneering Game Audio". Video Game Music Online. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- "Interview with: Nathan McCree". Platform Online. 27 November 2013. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- "Another recent interview". Troels Brun Folmann Website. 31 May 2006. Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Bright, Rob (November 1996). "Music Moods". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 13. Emap International Limited. p. 57.

- Interview, "NATHAN McCREE & MATT KEMP: Music For Computer Games" Archived 27 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Sound On Sound, May 2000

- "An Interview With Shelley Blonde-The Original Voice Of Lara Croft ǀ The Gaming Liberty". The Gaming Liberty. 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- "The Evolution of Tomb Raider". Game. 16 March 2018. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "She's Tough, She's Sexy, She's Lara Croft in Eidos' Tomb Raider for the PC, PlayStation, and Saturn (Press Release)". Core Design Fansite. 14 November 1996. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Tomb Raider for PC". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Makuch, Eddie (29 November 2012). "Tomb Raider 1-5 hit Steam". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Exclusive Extras For PlayStation Plus Members – PlayStation.Blog.Europe". PlayStation Blog. 13 August 2010. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Hood, Vic (22 March 2018). "Tomb Raider remasters cancelled because no one asked if they could make them". PC Games. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Tomb Raider Expansion Planned". Next Generation. 27 March 1997. Archived from the original on 5 June 1997. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Tomb Raider: Unfinished Business". Core Design. Archived from the original on 9 July 1998. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Labrad, David (1998). "Prospecting for Gold: An Interview with Tomb Raider Gold designer Philip Campbell". Adrenaline Vault. Archived from the original on 7 May 1998. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "The Life and Times of Phil Campbell". Phil Campbell Official website. Archived from the original on 20 December 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- Purchese, Robert (9 January 2020). "The amazing stories of a man you've never heard of". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- "Tomb Raider Gold: Unfinished Business". Tomb Raider website. Archived from the original on 11 May 2000. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Tomb Raider Gold: Shadow of the Cat". Tomb Raider website. Archived from the original on 12 May 2000. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Carmichael, Stephanie (6 December 2012). "These missing Tomb Raider games could be entombed for good". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Gibson, Joe (11 March 2003). "Tomb Raider (NNG)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "The Original Tomb Raider Hits Android Devices!". Square Enix. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Sci/Tech | 'Nude Raiders' face legal action". BBC News. 18 March 1999. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- IGN Staff (22 March 1999). "'Nude Raider' Crackdown". IGN. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- Legal Technology Insider, E-Business + Law Newsletter 30 (1999)

- GameTrailers (24 March 2013). Pop Fiction: Season 3: Episode 33: Nude Raider. YouTube (Video). Archived from the original on 19 December 2021.

- "Tomb Raider (1996) for PC". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- "Tomb Raider for PlayStation". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Tomb Raider for Saturn". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Tomb Raider I for iPhone/iPad Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- "Tomb Raider for PlayStation Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Computer and Video Games - Issue 181 (1996-12)(EMAP Images)(GB)". Archive.org. December 1996. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- "Tomb Raider Review | Edge Online". Edge. 17 March 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- "Review Crew: Tomb Raider". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 89. Ziff Davis. December 1996. pp. 84, 89.

- トゥームレイダース (PS). Famitsu. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- セガサターン - トゥームレイダース [Sega Saturn - Tomb Raiders]. Famitsu (in Japanese). No. 424. ASCII Media Works. 17 January 1997.

- "Tomb Raider Review". 20 October 2000. Archived from the original on 20 October 2000. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- "Game Revolution Review Page - Game Revolution". Game Revolution. 30 September 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- GamesMaster, issue 49, pages 34-37

- "Tomb Raider PC Review". GameSpot UK. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012.

- Sterbakov, Hugh (9 December 1996). "Tomb Raider PS1 Review". GameSpot.

- MacDonald, Ryan (1 December 1996). "Tomb Raider Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- "Tomb Raider im Gamezone-Test". Gamezone.de (in German). 26 April 2001. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- "Tomb Raider Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 12 November 2011.

- "Indiana Jonesing". Next Generation. No. 25. Imagine Media. January 1997. p. 180.

- Musgrave, Shaun (31 December 2013). "'Tomb Raider I' Review – Disastrous Controls Destroy An Otherwise Good Port". TouchArcade. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- Automatic, Rad (November 1996). "Review: Tomb Raider". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 13. Emap International Limited. pp. 70–71.

- Bro' Buzz (January 1997). "Saturn ProReview: Tomb Raider". GamePro. No. 100. IDG. p. 110.

- Bro' Buzz (February 1997). "PlayStation ProReview: Tomb Raider". GamePro. No. 101. IDG. p. 66.

- "Finals". Next Generation. No. 43. Imagine Media. July 1998. p. 118.

- "Computer Games Strategy Plus announces 1996 Awards". Computer Games Strategy Plus. 25 March 1997. Archived from the original on 14 June 1997. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- The Gamecenter Editors. "The Gamecenter Awards for 96". CNET Gamecenter. Archived from the original on 5 February 1997.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - "The Best of '96" (PDF). Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 92. Ziff Davis. March 1997. pp. 82–90.

- "Spotlight Award Winners". Next Generation. No. 31. Imagine Media. July 1997. p. 21.

- "100 Best Games of All Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 100. Ziff Davis. November 1997. p. 126.

- The PC Gamer Editors (October 1998). "The 50 Best Games Ever". PC Gamer US. 5 (10): 86, 87, 89, 90, 92, 98, 101, 102, 109, 110, 113, 114, 117, 118, 125, 126, 129, 130.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Cork, Jeff (16 November 2009). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games Of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- Newsweek (10 June 1997). "Article in Newsweek". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 25 April 2005. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- "Eidos Interactive's Tomb Raider Wins Several Game of the Year Awards and a Codie. - Free Online Library". Thefreelibrary.com. 10 March 1997. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- Rothstein, Edward (8 December 1997). "Nintendo's Game Boy lives as nostalgia for simpler computer games catches on". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Uhr TCM Hannover – ein glänzender Event auf der CebitHome" (Press release) (in German). Verband der Unterhaltungssoftware Deutschland. 26 August 1998. Archived from the original on 13 July 2000.

- "VUD Sales Awards: November 2002" (Press release) (in German). Verband der Unterhaltungssoftware Deutschland. Archived from the original on 10 January 2003.

- Horwitz, Jer (15 May 1997). "Saturn's Distant Orbit". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 12 March 2000.

- "Eidos Celebrates with Lara Croft Tomb Raider: Anniversary". GameSpot. 30 October 2006. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "At 8.5 million units sold, Tomb Raider's 2013 reboot is the franchise's top seller". VentureBeat. 6 August 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "Recommended Acquisition of Eidos plc by SQEX Ltd" (PDF). Square Enix. 30 March 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- "Top 50 Games of All Time" (PDF). Next Generation. No. 50. Imagine Media. February 1999. p. 78.

- GameSpot Staff (2001). "GameSpot Presents: 15 Most Influential Games of All Time". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- Official UK PlayStation Magazine issue 108, page 28, Future Publishing, March 2004

- Origin Awards, List of Winners, 1997

- "BAFTA Awards". awards.bafta.org. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Tomb Raider". The Strong National Museum of Play. The Strong. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Funk, Joe (August 1997), "Insert Coin (Editorial)", Electronic Gaming Monthly, p. 6, archived from the original on 28 February 2005, retrieved 31 July 2007

- Crystal Dynamics (1 June 2007). Tomb Raider Anniversary – Developer Diary 5 (Video). Eidos Interactive, The Gamer's Temple. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021.

- Dobson, Jason (1 June 2007). "Q&A: Crystal Dynamics' LaMer On 10 Years Of Tomb Raiding". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- Glover, Chris (19 June 2006). "Eidos confirms '10th Anniversary Edition' of Tomb Raider". SCi Entertainment. Archived from the original on 12 February 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Sinclair, Brendan (17 October 2007). "Tomb Raider: Anniversary 360 dated". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Casamassina, Matt (14 May 2007). "Eidos Talks Wii Lara Croft". IGN. Archived from the original on 19 May 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Doolan, Liam (15 January 2022). "Random: The OG Tomb Raider Looks Amazing On Game Boy Advance". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- Zwiezen, Zack (15 January 2022). "Someone Got PS1 Classic Tomb Raider Running On A Game Boy Advance". Kotaku. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- Devetis, Anthony (17 January 2022). "Modder Gets PS1 Classic Tomb Raider Running On a Game Boy Advance". GameRant. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

Further reading

- Sawyer, Miranda (June 1997), "Lara hit in The Face", The Face, archived from the original on 9 April 2007, retrieved 31 July 2007

- Blache III, Fabian; Fielder, Lauren (2002), The History of Tomb Raider, GameSpot, archived from the original on 14 February 2009, retrieved 31 July 2007